The Paris Review's Blog, page 688

July 2, 2014

Elizabethan Warts and All, and Other News

Detail from “Treatment for lachrimal fistula performed on a nun,” an illustration from a seventeenth-century surgical guide. Via Wellcome Library.

A report by British dermatologists makes the audacious claim that Shakespeare is responsible for Western society’s obsession with clear skin. “Shakespeare’s works have survived the intervening centuries; has his success led to the perpetuation of Elizabethan negativity toward skin disease?” Apparently, too many of his plays feature insults about skin disease—poxes, boils, carbuncles, moles, blots, blemishes, plagues—an excess of abscesses, a sebaceous surfeit.

“One of the most intriguing questions I get from readers of my movie reviews is: ‘But did you like the film?’ … The binary scale of good and bad, like and dislike, is essentially pointless. Movies are complex experiences—even those that are simplistic or clumsily made are rich in substance—and sometimes criticism is like the science of medicine, with advances coming from diagnoses of some dread disease that you wouldn’t want to have.”

A linguist’s cri de coeur: death to Whorfianism! “What Whorfianism claims, in its strongest form, is that our thoughts are limited and shaped by the specific words and grammar we use”—but linguists have found only “fairly negligible differences … between language speakers.”

These hand-painted posters from Russian cinemas make movies like Shrek 2 and 50 First Dates look like surrealist masterworks.

You can live in the house from Twin Peaks. (Leland Palmer not included. Or is he?)

July 1, 2014

Swinging for the Fences

The Paris Review’s Hailey Gates, Stephen Andrew Hiltner, and Clare Fentress at the game against The New Yorker last week.

A certain literary quarterly graced Page Six this morning, and it’s not because we’re in rehab or recently posed nude or hosted a tony, freewheeling charity dinner in Sagaponack—though we aspire to do those things, ideally all at once.

No, it’s because we have a damn fine softball team.

Fact is, The Paris Review Parisians are on something of a hot streak; in our five games this season, we’ve met with defeat only once, at the hands of The Nation. And we play a good clean game: no pine tar, no corked bats, no steroids (unless you count the occasional can of Bud Light). We believe, like Susan Sarandon in Bull Durham, in the Church of Baseball. It was only a matter of time until we attracted the attention of the gossip rags. Says the Post of our game against Harper’s last week,

“A string of ‘Parisian’ homers” put eight more runs on the board … the “mercy rule” was invoked—meaning nobody kept count … A spy said of The Paris Review’s crew that also pummeled The New Yorker two days earlier: “Their team was so good-looking and so coordinated, I could hardly believe any of them actually knew how to read. Let alone know what to do with a semicolon.”

The print version of the piece puts an even finer point on it: “Literary sluggers in rout,” its headline says.

In just a few hours, the Parisians—now well acquainted with the art of being vain—take on Vanity Fair, itself no stranger to Page Six. What’s at stake is more than just bragging rights: it’s what John Updike called, in “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” “the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill.”

Your Summer Reading, Sorted

We’re delighted to announce a summer-long joint subscription deal with The London Review of Books.

For sixty years, The Paris Review has published what’s best and most original in American writing; since 1979, The London Review of Books has set a standard for long-form literary journalism, with essays that examine every aspect of world culture. Now, for a limited time only, you can get a year’s subscription to both magazines for one low price: $60 U.S. It’s reading for all seasons, starting today.

Futurism on Wheels, and Other News

The Torpedo-GAZ, from 1951—a Soviet concept car with a tubular duraluminum skeleton. Via io9.

The nineteenth century “had its own explosion of media … Much as with today’s web, people complained there was too much to read … The solution to overload? For tens of thousands of Americans, it was the scrapbook.”

Authors turn to pseudonyms for a number of reasons—some strange, some prosaic, some almost metaphysical. In Sarah Hall’s case, the problem was : “I could never be published as me. Someone had got there first … my agent reminded me, gently: ‘I really don’t think you can be Sarah Hall.’”

An interview with Jeff Sharlet, whose new book looks at religion in America: “In nine out of ten cases ‘spirituality’ is a con—not a con by the person invoking it, but a con on that person. It offers the illusion of individual choice, as if our beliefs, or our rejection of belief, could be formed in some pure Ayn Randian void … We’re caught up in a great, complicated web of belief and ritual and custom. That’s what I’m interested in, not the delusion that I’m some kind of island.”

“It felt like the water was rising and lapping just under my nose … I really began to wonder whether my career was over.” Classical musicians contend with stage fright.

Soviet concept cars from the fifties and sixties show what might have been, had futurism held its grip on the national imagination—these sleek, modular vehicles are a striking counterpoint to the American cars of the era.

June 30, 2014

A Worshipper of Flowing

A sketch of Miłosz by Zbigniew Kresowaty.

A happy birthday to Czesław Miłosz, who was born today in 1911 and died in 2004. Miłosz nursed a lifelong fascination with science and naturalism, particularly as they were reconciled—or not—with the Catholic teachings of his youth. He outlined the opposition in his 1994 Art of Poetry interview:

INTERVIEWER

What fascinated you about nature?

MILOSZ

Well, my great hero was Linnaeus; I loved the idea that he had invented a system for naming creatures, that he had captured nature that way. My wonder at nature was in large part a fascination with names and naming. But I was also a hunter. So was my father. Today I am deeply ashamed of having killed birds and animals. I would never do that now, but at the time I enjoyed it. I was even a taxidermist. In high school, when I was about thirteen or fourteen, I discovered Darwin and his theories about natural selection. I was entranced and gave lectures about Darwin in our naturalists’ club. But at the same time, even though it was a state school, the priests were very important. So on the one hand, I was learning about religion, the history of the Church, dogmatics, and apologetics; on the other hand, I learned about science, which basically undermines religion. Eventually I turned away from Darwinism because of its cruelty, though at first I embraced it. Nature is much more beautiful in painting, in my opinion.

INTERVIEWER

Can a connection be made between the naturalist’s and the poet’s appreciation of nature?

MILOSZ

David Wagoner has written a poem called “The Author of American Ornithology Sketches a Bird, Now Extinct.” It’s a poem about Alexander Wilson, one of the leading ornithologists in America, shooting and wounding an Ivory-billed woodpecker, which he kept to draw because it was a specimen that was new to him. The bird was slowly dying in his house. Wilson explains that he has to kill birds so that they can live on the pages of his books. It’s a very dramatic poem. So the relation of science to nature, and I suspect also of art to nature, is a sort of a meeting of the minds of both scientist and artist in that they both have a passion to grasp the world …

That passion is in evidence throughout “Rivers,” a prose poem by Miłosz published in our Summer 1998 issue; here the geological and religious meanings of rivers are made to sit—illuminatingly, if not comfortably—next to each other. It’s an appropriately crisp read for a humid summer evening, and it begins:

“So lasting they are, the rivers!” Only think. Sources somewhere in the mountains pulsate and springs seep from a rock, join in a stream, in the current of a river, and the river flows through centuries, millennia. Tribes, nations pass, and the river is still there, and yet it is not, for water does not stay the same, only the place and the name persist, as a metaphor for a permanent form and changing matter. The same rivers flowed in Europe when none of today’s countries existed and no languages known to us were spoken.

Read the whole poem here.

Be Afraid

The political fear of soccer; how to shame a pathological diver.

Rama V, via Flickr.

As Americans continue to watch the World Cup in their accumulating millions, the denizens of the political right are running scared. Ann Coulter, whose bark is worse than Suárez’s bite—and whose delusions match José Mujica’s, the President of Uruguay, who referred to FIFA’s punishment of his country’s star as a “fascist ban”—weighed in a few days ago with a column listing the myriad ways in which soccer is un-American. It would be hard to find someone who knows less about soccer than Ann Coulter, but as Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel would say, that’s nit-picking, isn’t it? So: soccer doesn’t reward “individual achievement.” It’s “foreign,” meaning French people, liberals, and fans of HBO’s Girls like it. And, perhaps worst of all, it’s wussy: the “prospect of personal humiliation or major injury” essential to receiving the Coulter seal of approval as a real sport, like hockey or American football, is apparently missing in soccer.

Peter Beinart, writing in the Atlantic, has an interesting take on Coulter’s silliness: She’s right to be scared of the World Cup. Why? Because its burgeoning devotees look a lot like the people who elected Obama—first generation immigrants and their children, Hispanics, young people, and, yeah, liberals, who like soccer because they get to play with rest of the world instead of apart from it. Ann the Fan prefers it when Americans aren’t contaminated this way; better just to have a little local competition and call it the World Series.

Fans of Team USA have bought more tickets than any group outside the host country to this year’s tournament. And there they are in the stands, whooping it up, win or lose—reveling, it seems, in being part of a truly international party. Will the enthusiasm last? The test will come, possibly as early as tomorrow, if the U.S. loses. Will the nation switch off? I don’t think so.

Arjen Robben, Holland’s left-footed winger, is a brilliant player, one of the world’s best, and he is also a self-acknowledged cheat. He likes to draw fouls and fool refs by taking dives. It’s hard to discern when he’s faking, because he also happens to get fouled a lot; he’s fast and elusive and players from the other teams are not shy about kicking him up in the air. In yesterday’s game against Mexico, he went to ground three times. On the last occasion, in the final minute of the game, he won a penalty, Klaas Jan Huntelaar scored from the spot, and Holland had its victory. Afterward, Robben had no problem admitting to an inconsequential earlier dive, but he wouldn’t fess up to any late shenanigans. Clearly Mexico’s captain Rafael Márquez made contact, but Robben’s subsequent leap was spectacular theater—cirque de (Francois) Hollande.

When he played for Tottenham Hotspur in the midnineties, Jurgen Klinsmann, the present coach of the U.S. team, was an infamous diver. At away games, fans would hold up handwritten numerical signs to score his Olympian efforts: 5.6, 4.9, 6.0. Perhaps that’s how we need to shame Robben. Costa Ricans, get your numbers ready for Saturday.

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

Comfort Food

Sally Bell’s started making box lunch in the 1950s, but the recipes used to make the salad, sandwich spread, deviled egg, cheese wafer, and cupcake that go into the box date back to the 1920s, when Sarah Cabell Jones opened her bakery in a building across the street. There is nothing singly spectacular about the immemorial meal you get here, except for its immunity to anything modern. Sally Bell serves the exact lunch it served a half-century ago, which is probably much the same as polite Virginians ate a hundred years ago. There are two salads from which to choose: macaroni, which is fine, and spicy-sweet potato salad laced with onions, which is memorable. Of the eleven kinds of sandwiches, we seldom can resist pimiento cheese, but we have not regretted chicken salad (on a roll rather than white bread), cream cheese and olive (talk about a bygone taste!), and thin-cut Smithfield ham. As for cupcakes, there’s no beating the orange-and-lemon, its icing sprinkled with little bits of citrus confetti. All the elements are neatly packaged in a cardboard lunchbox lined with wax paper.

—Jane and Michael Stern, Roadfood

Sally Bell’s Kitchen is hardly a secret. It is a Richmond institution, beloved by generations of Fan District denizens, and the subject of a lengthy profile, in 2000, in the New York Times. Saveur calls its box lunch “paradise in a box.” Its demure, upside-down cupcakes, twenties-vintage Colonial Dame logo, deviled eggs, and old-fashioned, pecan-crowned cheese wafers—described by the Sterns as “heartbreaking”—speak to a sort of timeless gentility most of us can only imagine.

Certainly I can. I have no ties to Richmond, no institutional memory of the place. The three times I’ve tried to visit Sally Bell’s, I’ve fallen victim to the bakery’s conservative hours. And yet my obsession with the place is so well known that friends have more than once taken the time to wait on line and rush me a box lunch up to New York. People have given me aprons emblazoned with the cameo logo and a picture book filled with mouthwatering images of deviled eggs and beaten biscuits. On occasion I have been known to print out a copy of their menu and quixotically check off the options that appeal to me: potato salad, ham roll, lemon cupcake. For a while I had this pinned over my desk at work. I imagine people found this eccentric; in fact, I found it deeply comforting. Sally Bell’s—or my dream of it, anyway—has somehow become my happy place: a magical, cozy, well-ordered, old-fashioned realm filled with immutable recipes and homemade mayonnaise. Never mind that these aren’t the foods I grew up with; they have somehow become, for me, the definition of comfort. When I’m sad or disoriented, I pull down my book and pore over those pictures. I watch this film again and again, and I cry for reasons I can’t even explain to myself.

I am aware I am romanticizing something that requires plenty of hard work and dedication. But it has become more than merely an idea of some kind of gauzy Southern gentility. The other day, a friend of mine had some worries. I didn’t know how to help, but as I wandered the aisles of the supermarket, I found myself buying the components for homemade mayonnaise, and a soft roll for sandwiches—something I never normally do—and even keeping my eyes open for a white bakery box in which to pack it. I was trying to make a box lunch, to translate this mysterious totem of comfort to someone else. I am sure my friend was confused, but somehow understood that it was something important—that I was trying hard. At the end of the day, what more can we do?

Recapping Dante: Canto 34, or “It Is Time for Us to Leave”

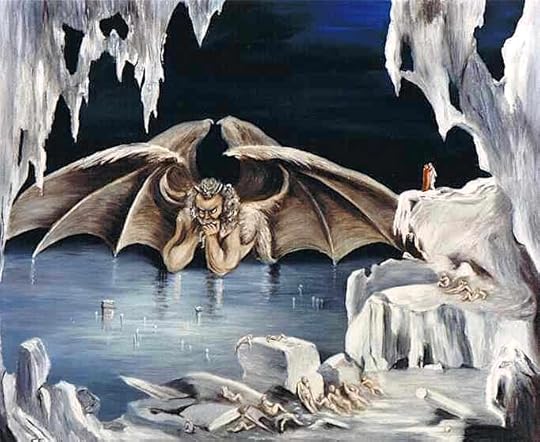

A colorized version of Gustave Doré’s illustration for Canto XXXIV.

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: the final canto.

My relationship with Dante can be traced back to a Saturday morning in 1994. My dad and I were standing in the rain on Sixty-Sixth and Broadway, and I suspected he was taking me to Lincoln Center for a concert. Instead, we stopped at a small park where a large, bronze statue was shrouded by nearby trees, hidden away from the city. That, he told me, is Dante.

The night before, my dad had told me the story of Count Ugolino, the sinner of canto 33 who may or may not have eaten his children during his imprisonment in Pisa; and later that day, he’d take me to the courtyard at St. John the Divine, where a statue of a crab-like creature pinches off the head of a demon—a scene that bears a striking resemblance to the end of Dante’s Inferno, when the three-headed Lucifer gnashes his teeth around the bodies of the three greatest sinners: Judas, Brutus, and Cassius. Here, in canto 34, the final chapter, Dante and Virgil meet Lucifer and climb up his back in order to slip through a crack in the universe and leave the Inferno.

It wouldn’t occur to me for many more years that these weren’t stories from my dad, but the work of the better craftsman, or il miglior fabbro, as T. S. Eliot writes in the dedication of “The Waste Land,” paraphrasing Dante himself. In fact, if I look hard enough, I find traces of Dante throughout my life—a description of the wolf, lion, and leopard in the elevator of 765 Amsterdam Avenue, the building where my grandparents lived; the story of Paolo and Francesca, which I read in an illustrated, abridged Inferno for children; the fiberglass tyrannosaurus in Riverside Park, which I climbed as though I were Virgil scaling Lucifer’s back with Dante in order to reach Purgatory at the end of canto 34; a twig from a tree that I passed on a field trip in a botanical garden, which I tore off à la Dante in canto 13, so that my dad, a reluctant chaperone, would know that I wanted to be there as little as he did. As far as I knew, I wasn’t alluding to Pier delle Vigne but to a character from my father’s bedtime mythology. None of these tales came without embellishments, and so even today, when I reread passages of the Inferno and notice departures from the stories I heard growing up, I cannot help but think that Dante Alighieri’s versions are slightly inaccurate. Even so, by the time I reach someone like Ugolino, I feel as if I’m meeting an old friend.

As I finished reading canto 34—the last installment of an eight-month series—I realized that one of its most famous passages is often horribly misinterpreted. After Virgil tells his traveling companion which sinners Lucifer is chewing, he tries to prod the ever-dillydallying Dante onward: “It is time for us to leave, for we have seen it all.” But how could that possibly be? Is the Inferno really a place we hope never to revisit? Can we really ever be done with it? If that’s the case, then why am I more moved by certain passages than ever before?

One can’t really find oneself jaded by Dante. Every time I go over the text I leave another set of earmarks; I come away with another history lesson; I leave another few notes on the sides of the pages in another color of ink, crossing out the scribbles that no longer seem quite as poignant and underlining the ones that do. Rereading Dante forces us to collect layers.

So can we ever really have seen it all? Even Virgil, who speaks these lines, is already taking his second trip through the Inferno. Perhaps what he really means to say is, “You’ve seen as much as you’re going to see this time around, pal.” So I’ll continue reading, and if I tire, I’ll just have to remember another Hallmark-worthy line spoken by Virgil: “Get to your feet, for the way is long and the road is not easy.”

Rereading makes me feel close to Dante, and so I wonder: Will I ever get to take a son of my own to Dante Park? Will I ever stand on Sixty-Sixth and Broadway in the rain, hoping that seeing this statue might shed light on a story about an Italian cannibal that I told a preschooler? And if said preschooler is too tired to walk, will he hook his arms around my back, the way I did with my father, and the way—which is perhaps totally irrelevant—that Dante did with Virgil as they climbed to Purgatory?

In the final few verses of canto 34, Virgil and Dante finally see the night sky as they exit hell. They hear a nearby stream. I started to feel sentimental rereading this: “The sound of a narrow stream … trickles through a channel it has cut into the rock in its meanderings, making a gentle slope.” Is that the Hudson I hear outside my window, or is it the water trickling from the air conditioner and pooling right above the double pane? Or am I imagining it all, hoping that if I try hard enough I might be able to drown out the sound of the city’s late-night traffic and hear the water sloshing between here and New Jersey, pretending I’m actually right beside Dante and Virgil. For a moment I can pretend that I’m Dante, the poet in exile, sitting far from home and trying to remember what the Arno sounds like at night in Florence, imagining that by some strange coincidence it might perhaps even sound just like a little brook nuzzling its way through a boulder beneath the starlight at the far end of the world.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Recapping Dante: Canto 34, or “It Is Time For Us to Leave”

A colorized version of Gustave Doré’s illustration for Canto XXXIV.

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: the final canto.

My relationship with Dante can be traced back to a Saturday morning in 1994. My dad and I were standing in the rain on Sixty-Sixth and Broadway, and I suspected he was taking me to Lincoln Center for a concert. Instead, we stopped at a small park where a large, bronze statue was shrouded by nearby trees, hidden away from the city. That, he told me, is Dante.

The night before, my dad had told me the story of Count Ugolino, the sinner of canto 33 who may or may not have eaten his children during his imprisonment in Pisa; and later that day, he’d take me to the courtyard at St. John the Divine, where a statue of a crab-like creature pinches off the head of a demon—a scene that bears a striking resemblance to the end of Dante’s Inferno, when the three-headed Lucifer gnashes his teeth around the bodies of the three greatest sinners: Judas, Brutus, and Cassius. Here, in canto 34, the final chapter, Dante and Virgil meet Lucifer and climb up his back in order to slip through a crack in the universe and leave the Inferno.

It wouldn’t occur to me for many more years that these weren’t stories from my dad, but the work of the better craftsman, or il miglior fabbro, as T. S. Eliot writes in the dedication of “The Waste Land,” paraphrasing Dante himself. In fact, if I look hard enough, I find traces of Dante throughout my life—a description of the wolf, lion, and leopard in the elevator of 765 Amsterdam Avenue, the building where my grandparents lived; the story of Paolo and Francesca, which I read in an illustrated, abridged Inferno for children; the fiberglass tyrannosaurus in Riverside Park, which I climbed as though I were Virgil scaling Lucifer’s back with Dante in order to reach Purgatory at the end of canto 34; a twig from a tree that I passed on a field trip in a botanical garden, which I tore off à la Dante in canto 13, so that my dad, a reluctant chaperone, would know that I wanted to be there as little as he did. As far as I knew, I wasn’t alluding to Pier delle Vigne but to a character from my father’s bedtime mythology. None of these tales came without embellishments, and so even today, when I reread passages of the Inferno and notice departures from the stories I heard growing up, I cannot help but think that Dante Alighieri’s versions are slightly inaccurate. Even so, by the time I reach someone like Ugolino, I feel as if I’m meeting an old friend.

As I finished reading canto 34—the last installment of an eight-month series—I realized that one of its most famous passages is often horribly misinterpreted. After Virgil tells his traveling companion which sinners Lucifer is chewing, he tries to prod the ever-dillydallying Dante onward: “It is time for us to leave, for we have seen it all.” But how could that possibly be? Is the Inferno really a place we hope never to revisit? Can we really ever be done with it? If that’s the case, then why am I more moved by certain passages than ever before?

One can’t really find oneself jaded by Dante. Every time I go over the text I leave another set of earmarks; I come away with another history lesson; I leave another few notes on the sides of the pages in another color of ink, crossing out the scribbles that no longer seem quite as poignant and underlining the ones that do. Rereading Dante forces us to collect layers.

So can we ever really have seen it all? Even Virgil, who speaks these lines, is already taking his second trip through the Inferno. Perhaps what he really means to say is, “You’ve seen as much as you’re going to see this time around, pal.” So I’ll continue reading, and if I tire, I’ll just have to remember another Hallmark-worthy line spoken by Virgil: “Get to your feet, for the way is long and the road is not easy.”

Rereading makes me feel close to Dante, and so I wonder: Will I ever get to take a son of my own to Dante Park? Will I ever stand on Sixty-Sixth and Broadway in the rain, hoping that seeing this statue might shed light on a story about an Italian cannibal that I told a preschooler? And if said preschooler is too tired to walk, will he hook his arms around my back, the way I did with my father, and the way—which is perhaps totally irrelevant—that Dante did with Virgil as they climbed to Purgatory?

In the final few verses of canto 34, Virgil and Dante finally see the night sky as they exit hell. They hear a nearby stream. I started to feel sentimental rereading this: “The sound of a narrow stream … trickles through a channel it has cut into the rock in its meanderings, making a gentle slope.” Is that the Hudson I hear outside my window, or is it the water trickling from the air conditioner and pooling right above the double pane? Or am I imagining it all, hoping that if I try hard enough I might be able to drown out the sound of the city’s late-night traffic and hear the water sloshing between here and New Jersey, pretending I’m actually right beside Dante and Virgil. For a moment I can pretend that I’m Dante, the poet in exile, sitting far from home and trying to remember what the Arno sounds like at night in Florence, imagining that by some strange coincidence it might perhaps even sound just like a little brook nuzzling its way through a boulder beneath the starlight at the far end of the world.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Outrageous Apples, and Other News

Infuriating, no? Paul Cézanne, The Kitchen Table (La table de cuisine), 1888–90.

The Irish poet and novelist Dermot Healy has died at sixty-six. “I think of him as someone who lived on the edge, in some way … He lived on the very edge of County Sligo, the edge of Ireland—the edge of Europe, you might say. In some ways he lived on the edge of the literary community, but in certain ways he was central to the community he shaped around himself, especially in the northwest of Ireland. And it was the rough edge of his work, which in some ways was so distinctive, which attracted his readers.”

And the poet Allen Grossman has died at eighty-two; “poetry is a principle of power invoked by all of us against our vanishing,” he once said.

In happier news, astronomers have discovered the biggest diamond in the universe: it “weighs approximately a million trillion trillion pounds … Nobody has actually seen this gigantic diamond, not even through a telescope … the star’s invisibility is a key part of the circumstantial case for its existence.”

Cézanne’s “paintings of apples confused critics and art enthusiasts alike. People were astonished that apples could look so ugly, and be so poorly painted. Some thought Cézanne’s still lifes were actually a joke, or an insult.”

On elevators (and the people in them): “You can only send yourself as a message successfully if you remain intact—that is, fully encrypted—during transmission. That’s what elevator protocol is for. Or so we might gather from the very large number of scenes set in lifts in movies from the 1930s onwards … Desire erupts, or violence, shattering the sociogram’s frigid array. Or the lift, stopped in its tracks, ceases to be a lift. It becomes something else altogether: a prison cell to squeeze your way out of, or (Bernard suggests) a confessional.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers