The Paris Review's Blog, page 684

July 14, 2014

Schadenfreude

Götze kicks the match-winning goal. Photo: Danilo Borges/Portal da Copa, via Wikimedia Commons

How apt that the Brazilians are living off Schadenfreude: after the debacle against Germany and a little extra humiliation from Holland, all Brazil’s fans seemed to want was for Germany to prevent Argentina from victory dancing on the beach at Copacabana. Believe me, I get it. As a lifelong supporter of Tottenham Hotspur F.C. in the English Premier League, much of my soccer pleasure in the last half-century, sadly, has derived only from misfortunes experienced by Arsenal F.C., Tottenham’s arch rivals. In the years 1960–1962, Tottenham was clearly the superior team—since then, not so much. Like Brazil and Argentina, the two clubs are neighbors, and Arsenal, like Brazil, has the larger fan base and more money.

But I want to tell you, Brazilians: Schadenfreude (yours and mine) is unhealthy. It mocks the meat it feeds on. Brazil (population two hundred million) is in a much better position that Argentina (population forty-one million) to do something to transform its lackluster team into world-beaters. They need look no further than Germany, where, over a twenty-year period, an entire system from youth soccer up was revamped in the wake of defeat and disappointment to produce the superior team that yesterday won the World Cup in style: a triumph that not a soul would deny they deserved. Is this why the U.S. keeps spying on Deutschland? Looking for the blueprint that will take us to number one? Or are we simply after Angela Merkel’s recipe for Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte?

The sun set behind Christ the Redeemer, and then Argentina went down, too. Lionel Messi won the Golden Ball for best player in the tournament (not that he cared), but it could just as easily have gone to Arjen Robben or Bastian Schweinsteiger or Javier Mascherano. After two overtime games in five days, Messi looked, at times, as if he were walking through treacle. When, as the final minutes ticked away, he stepped up to take his last do-or-die free kick, he was already a forlorn figure; that ball was going wide, or over the bar, and everyone in the Maracanã knew it. Messi’s problem? He was too much on his own, dropping ever deeper, as if a retreat into the shadows of his own half would conjure a Di María to run back up the field with him. In his most successful years, Pelé was surrounded by players of great genius—Garrincha, Tostão, Jairzinho, and Rivelino—individuals with talents that didn’t quite match the master’s, but enabled them to provide stellar support. While Mascherano was a beast in the Argentine defense, Messi had no one quite at the level required for his game to shine at its brightest. He’ll have to return to Barcelona for that.

Of course, there’s always the feeling that he should have been able to do it on his own—a feat Maradona is believed to have accomplished in World Cup 1986, when he scored or assisted on ten of Argentina’s fourteen goals. But, even with the great Lothar Matthäus on board, the West Germany that Argentina beat in that final was not at the same level as Germany 2014, the first team to win a major international championship since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Where Germany is concerned, everyone reaches for the engineering metaphors—it’s knee-jerk—and, this time around, it doesn’t apply. Okay, Germany is well coached: Is this why Ian Darke, the English ESPN/ABC commentator, described Jogi Löw as resembling a Bond villain? Baffling. The team played with a smoothness not like that of a well-oiled machine, but more like that of the movements of choreographed dancers. It looked like art out there, not industry. Certainly Mario Götze’s lovely goal from André Schürrle’s cross was full of grace: one swift movement, chest to foot to back of net. Götze’s father is a professor of computer science at Dortmund University. His son’s goal may be the best thing that has happened to academia this century.

I’ve watched fourteen World Cups, and 2014 is the best I can remember since 1970, bites and all. And now we move on to Putin-land, where Russia (population 146 million) will take on their greatest rivals, the eleven courageous young women of Pussy Riot.

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

Hitty, Her Second Hundred Years

On Saturday, in Maine, I rode my bicycle the mile and a half to the very comfortable Northeast Harbor Library, which contains well-stocked “Maine” and “Garden” rooms; it’s currently showcasing a collection of antique “woolies,” folk-art embroideries made by extremely secure nineteenth-century sailors. Patrons who wish to memorialize their visit may buy “postal cards,” which are subcategorized accurately under such headings as “Circulation Area” and “Reference Desk.” I bought six for a dollar.

It is always awkward to be the only adult in the children’s room, and repetition does not make it any easier. But I went down the hall, past the mat where very young children have story time. I took a left at an enormous stuffed mouse and ran my finger along the “F” shelf in chapter books until I came upon my quarry: Hitty, Her First Hundred Years.

I knew they would have it, not just because it won the Newbery in 1930 and is considered a classic, but because it is one of the great Maine children’s books. Hitty is an imagined history of a small doll carved from a piece of mountain ash—inspired by a real doll that its author, Rachel Field, found in a New York City antiques shop—which takes its heroine around the globe via whaling vessel and Missisippi river boat, and in the custody of many different children. But Hitty is born in Maine, specifically on Cranberry Island, some two nautical miles from the library itself. In the course of her travels, she bears witness to the events of the nineteenth century, all of which she relates with serene pragmatism, in the manner of a doll Forrest Gump.

That evening, as it happened, we were to travel by motorboat to Cranberry Island. I did not know with whom, or when—in the way of guests, or dolls, I had little agency in such matters—but I was secretly excited to know I’d be near the actual Preble House, where Hitty was “born,” and where, today, you can buy a flat, wooden Hitty doll that is “slept” one night in the historic home before being sold. If you want to visit the genuine article, you can see her in Stockbridge; if you covet a Hitty of your own, their are craftspeople all over the country carving facsimiles; and if you want to compare Hitty’s journey to that of Odysseus, well, you can do that, too.

What is it that so appeals to readers about the book? It’s clearly written, the pictures are great, the adventures slip along. Even so, it’s an unusual children’s book. Of course, Hitty is passive—a point that struck me, as an adult, in ways it never did as a child. She is carried by crows, dropped, chewed by cats, left under a church pew, stuffed in a horsehair sofa for ten years, dragged through the mud. Some owners are kind, others careless. All this she takes in stride. There’s something deeply comforting in this. Hitty is more than a reliable narrator; she’s a caretaker. She outlives all the children who play with her; that you can know this, as a child, and not be troubled by it is a testament to the author’s skill, I think.

I have always wanted to go to Cranberry and see the Preble House. That boat ride, to a bustling restaurant on a dock, may be as close as I will ever get. I looked for it as we approached the harbor—I’d looked up its coordinates before we left—but I don’t think I saw it. I ached to be so close. But a part of me was glad to have the decision taken out of my hands.

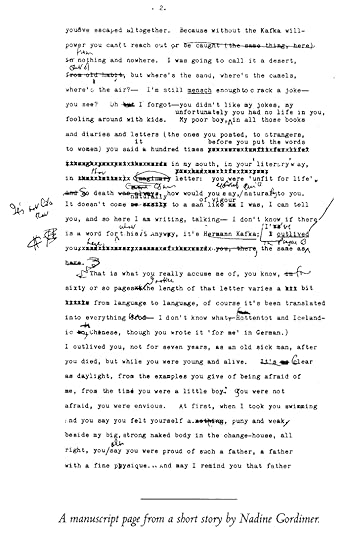

Nadine Gordimer, 1923–2014

Nadine Gordimer died yesterday in Johannesburg; she was ninety. Jannika Hurwitt described her, in an Art of Fiction interview published in our Summer 1983 issue, as “a petite, birdlike, soft-spoken woman”:

Gordimer manages to combine a fluidity and gentleness with the seemingly restrained and highly structured workings of her mind. It was as if the forty-odd years that she had devoted to writing had trained her to distill passion—and as a South African writer she is necessarily aware of being surrounded by passion on all sides—into form, whether of the written or spoken word.

As the Times obituary notes, Gordimer’s oeuvre constitutes “a social history as told through finely drawn portraits of the characters who peopled it … But some critics saw in her fiction a theme of personal as well as political liberation, reflecting her struggles growing up under the possessive, controlling watch of a mother trapped in an unhappy marriage.”

The Paris Review published three of Gordimer’s stories. The first, from 1956, is “Face from Atlantis” which appeared in our thirteenth issue, revealing her striking gifts as a portraitist:

Eileen had a favorite among the photographs of her, too … The photograph was taken in Austria, on one of Waldeck’s skiing holidays. It was a clear print and the snow was blindingly white. In the middle of the whiteness stood a young girl, laughing away from the camera in the direction of something or someone outside the picture. Her little face, burnished by the sun, shone dark against the snow. There was a highlight on each firm, round cheekbone, accentuated in laughter.

“Children with the House to Themselves” appeared in 1986, as part of our hundredth issue, and “Across the Veld,” from our Winter 1989 issue, is full of the carefully observed, intricately drawn tensions that animate Gordimer’s work—as in this paragraph below, in which Hannah, the protagonist, ventures, in a bus full of whites, through a black township:

An avenue of black faces looked into the windows, pressing close, so that the combis had to slow to these people’s walking pace in order not to crush them under the wheels. No picnic party; the whites surrounded by, gazed at, gazing into the faces of these blacks who had stoned white drivers on a main road, who had taken control of this township out of the hands of white authority, who had refused to pay for the right to exist in the decaying ruins of the war against their presence too close across the veld; these people who killed police collaborators in their impotence to stop the police killing their children. One thing to read about these people, empathize with them, across the veld. Hannah, in her hide, felt the fear in her companions like a rise in temperature inside the vehicle. She slid open the window beside her. Instead of stones, black hands reached in, met and touched first hers and then those of all inside who reached out to them. The passengers jostled one another for the blessing of the hands, the healing touch. Some never saw the faces of those whose fingers they held for a moment before the combi’s progress broke the grasp. From the crush outside there were the cries “AMANDLA! VIVA!,” and joy when these were taken up by the whites. In the smiling haze of weekend drunks this procession of white people was part of the illusions that softened the realities of the week’s labour and made the improbable appear possible. The crowd began to sing, of course, and toi-toi in a half-dance, half-procession alongside the convoy, bringing, among the raised fists of some in the combis, a kind of embarrassed papal or royal weighing-of-air-in-the-hand as a gracious response from some others.

“I would like to say something about how I feel in general about what a novel, or any story, ought to be,” Gordimer said to end her Art of Fiction interview. “It’s a quotation from Kafka. He said, ‘A book ought to be an ax to break up the frozen sea within us.’ ”

Islands in the Stream

The elephant in the discotheque: the Bee Gees.

A 1977 publicity photo of the Bee Gees for a television special, “Billboard #1 Music Awards.” From top: Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb.

The Bee Gees’ dominance of the charts in the disco era was above and beyond Chic, Giorgio Moroder, even Donna Summer. Their sound track to Saturday Night Fever sold thirty million copies. They were responsible for writing and producing eight of 1978’s number ones, something only Lennon and McCartney in 1963/64 could rival—and John and Paul hadn’t been the producers, only the writers. Even given the task of writing a song called “Grease” (“Grease is the word, it’s got groove, it’s got a meaning,” they claimed, hoping no one would ask, “Come again?”), they came up with a classic. At one point in March they were behind five singles in the American Top 10. In 1978 they accounted for 2 percent of the entire record industry’s profits. The Bee Gees were a cultural phenomenon.

Three siblings from an isolated, slightly sinister island off the coast of northwest England, already in their late twenties by the time the Fever struck—how the hell did they manage this? Pinups in the late sixties, makers of the occasional keening ballad hit in the early seventies, the Bee Gees had no real contact with the zeitgeist until, inexplicably, they had hits like “Nights on Broadway,” “Stayin’ Alive,” “Night Fever,” and the zeitgeist suddenly seemed to emanate from them. This happened because they were blending white soul, R&B, and dance music in a way that suited pretty much every club, every radio station, every American citizen in 1978. They melded black and white influences into a more satisfying whole than anyone since Elvis. Simply, they were defining pop culture in 1978.

Like ABBA, there is a well of melancholic emotion, even paranoia, in the Bee Gees’ music. Take “How Deep Is Your Love” (no. 1, ’77), with its warm bath of Fender Rhodes keyboards and echoed harmonies that camouflage the cries of the lyric: “We’re living in a world of fools, breaking us down, when they all should let us be … How deep is your love? I really need to know.” Or “Words,” with its romantic but strangely seclusionist “This world has lost its glory. Let’s start a brand-new story now, my love.” Or “Night Fever,” their ’78 number one, with its super-mellow groove and air-pumped strings masking the high anxiety of Barry Gibb’s vocal; the second verse is indecipherable, nothing but a piercing wail with the odd phrase—“I can’t hide!”—peeking through the cracks. It is an extraordinary record.

Total pop domination can have fierce consequences. Elvis had been packed off to the army; the Beatles had received Ku Klux Klan death threats—the Bee Gees received the mother of all backlashes, taking the full brunt of the anti-disco movement. Radio stations announced “Bee Gee–free weekends”; a comedy record called “Meaningless Songs in Very High Voices” by the HeeBeeGeeBees became a UK radio hit. Their 1979 album Spirits Having Flown had sold sixteen million copies and spawned three number-one singles (“Too Much Heaven,” “Tragedy,” “Love You Inside Out”); the singles from 1981’s Living Eyes—“He’s a Liar” and the title track—reached thirty and forty-five on the chart respectively, and didn’t chart in Britain at all. Almost overnight, nobody played Bee Gees records on the radio, and pretty much nobody bought them. The biggest group in the world at the end of 1978 went into enforced retirement three years later. Could they rise again? Of course they could.

* * *

In the beginning, there was big brother Barry and twins Robin and Maurice Gibb. They were born on the Isle of Man but moved to Manchester as children. And they were trouble, especially Robin, who loved setting fire to pretty much anything. He progressed quickly from bedclothes to billboards. One day a member of the Manchester constabulary came knocking and suggested to their parents that it was time to think about emigrating. Manchester’s problem became Australia’s, but the Gibbs started to channel their pyro activities into vocal harmonies—with no New York subway stations available, they practiced their art in public conveniences: “We always looked for the best toilets in town,” said Maurice.

Encouraged by their bandleader father, the brothers became a child act at working-men’s clubs, doing comedy routines and singing between races at the local speedway track. These were hard crowds to please. Bill Gates, a local DJ, began to promote them and they took their name from his and Barry Gibb’s initials—the Bee Gees. By 1960 they were on TV, singing “My Old Man’s a Dustman.” Their mum made their stage clothes. None of this exactly screamed international success.

It’s easy to forget that the Bee Gees were child performers, and that they grew up in such an odd, isolated way. Foraging, they found things they liked on the radio and absorbed them—the Everly Brothers, the Goons, Lonnie Donegan. Old Super 8 footage shows them goofing around, but you never see any other kids playing with them, just the three brothers. They only started playing in front of teenagers (who, sales figures suggest, were largely unimpressed) when they became teenagers themselves. This airtight upbringing informed their insularity, their prickly, defensive behavior, and many of their deeply strange early recordings: songs like “Holiday” (no. 11, ’67) and “I Started a Joke” (no. 6, ’68) suggest they were beamed down from another planet, aliens who had been given tiny scraps of information about what pop music was all about and were bravely trying to piece it together. By the time they left Australia, heading for the docks of Southampton in January 1967 to try to make a name for themselves back in Britain, they had released eleven singles, and none of them had meant very much at all. One of them, the admittedly excellent “Wine and Women,” had made it as far as number nineteen in Australia, but only after the group gave two hundred dollars to their school friends to buy copies. That was it. They sent tapes of their latest songs to Brian Epstein. For a failed fraternal comedy act, you had to admire their nerve.

Then something odd happened. Midway through their three-week voyage they heard that their eleventh single, “Spicks and Specks,” had gone to number one in New Zealand. And when they docked, they discovered that Brian Epstein’s sidekick Robert Stigwood was very interested in their tape. The raffish Stigwood booked them into a basement rehearsal room and asked them to write a hit. This sudden run of good luck seemed to desert them when there was a power cut. Finding themselves with no electricity, stuck in darkness at the bottom of a lift shaft, they came up with “New York Mining Disaster 1941.”

“Robin’s voice … still makes me go cold when I listen to him,” his mother once said, presumably meaning it as a compliment. There is something shivery as well as alien about the early Bee Gees records. As a child in the early seventies I had cassettes of the Beach Boys’ Greatest Hits and the sixties-era Best of Bee Gees. The similarity in the bands’ names led me to twin them, but musically and visually they were complete opposites. The Beach Boys, pictured smiling on a high-contrast bright white cover, sounded like the essence of summer; the Bee Gees, murkily shot on an old boat, no smiles, all shades of brown, were entirely autumnal. And what did their name mean? I wondered. It sounded like “Beach Boys” but drained of its meaning, mumbled, opaque—it suited the heaviness and obscurity of the music, rich in ninths and fully orchestrated, with hints of Celtic melancholy. So young, so sad.

In 1967 the Bee Gees were teenagers, literally straight off the boat, and Stigwood opened up the world to them. “The most significant new musical talent of 1967,” he called them. He threw down the challenge, and they thrived under pressure. “New York Mining Disaster 1941” gave them a Top 20 hit straight off. Clearly they were storytellers, and their third single, “Massachusetts,” about a weekend hippie trying to hitch a ride to San Francisco but ending up homesick and stranded, was number one in Britain and all over Europe by the end of ’67. Quickly they were compared to the Beatles, but their love of soul, and Bill Shepherd’s heavy-drape arrangements, gave them a distinctive and intense mournfulness. Stigwood asked them to write a song for Otis Redding—he had no intention of passing it on to Otis, but wanted to see what they were capable of. The result was “To Love Somebody,” only a number-seventeen hit, but a hardy, blue-eyed soul perennial. There was an emotional depth to their songs that gave them a rare advantage over the Beatles. George Martin had also produced the Action, a Kentish Town group who had worked up anglicized, uptight versions of things like the Marvelettes’ “I’ll Keep Holding On” and Bob and Earl’s “Harlem Shuffle”; the Bee Gees, in their own way, set themselves somewhere between the Beatles and the Action. Nobody else was staking out this territory. By late ’68 they had released three albums, scored a second UK number one (“I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You,” about a prisoner on death row, apparently written with Percy Sledge in mind), and a swathe of continental European number ones: “World,” “Words,” “I Started a Joke” (“which started the whole world crying”). Eighteen months after docking in Southampton, they were white pop’s greatest hope.

Still, they were brothers, and cooped up together they started to fight. Barry loved pot, Robin loved pills, Maurice was always out boozing with Ringo Starr. (Who could blame him? Just months earlier he’d been a fifteen-year-old Beatles fan-club member.) This chemical imbalance led them to split after 1969’s Odessa, a wildly ambitious double album housed in a red velvet sleeve. Robin, unmoored, more or less unhinged, quit the group and cut a solo single called “Saved by the Bell.” Over a primitive drum machine he’d found in Soho, his ethereal vibrato sang a sad-spaniel song that made “New York Mining Disaster 1941” sound like “Surfin’ USA.” In short order, he cut two albums of similarly vast, equally downbeat material (Robin’s Reign and the still unreleased Sing Slowly Sisters). Singing with closed eyes, a cupped hand over his ear, he may have seemed a delicate flower on stage, but he didn’t lack ambition. He had “completed a book called On the Other Hand which is to be published soon,” the NME reported. “ ‘I’m a great admirer of Dickens.’ ” In the few weeks between leaving the Bee Gees and hitting the chart with “Saved by the Bell,” he wrote more than a hundred songs. “I’m also doing the musical score for a film called Henry the Eighth,” he told Fabulous, “and I’m making my own film called Family Tree. It involves a man, John Family, whose grandfather is caught trying to blow up Trafalgar Square with a homemade bomb wrapped in underwear.” In July ’69 the NME announced that Robin was “fronting a 97-piece orchestra and a 60-piece choir in a recording of his latest composition ‘To Heaven and Back,’ which was inspired by the Apollo 11 moonshot. It is an entirely instrumental piece, with the choir being used for ‘astral effects.’ ” Robin Gibb was still only nineteen years old.

With his solo career, Robin had tried to leave home but found he couldn’t; the filial pull was too strong. When the Bee Gees first appeared in ’67, the depth of their songs cut through on the radio like a beacon through fog. By 1970, though, they were the fog, lost in over-ambitious, undercooked records (Maurice and Barry both cut mopey, unreleased solo albums). Right at the end of the year, they got back together. Initially the reunion worked beyond anything they could have hoped for—the first two songs they came up with were “Lonely Days” and “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart,” autobiographical, self-healing songs which reached number three and number one respectively. Their success led the Gibbs to abandon their sky-reaching, orchestrated pop, and they settled for an easy country-ballad sound which threw up the occasional gem (“Run to Me,” no. 16, ’72) but had entirely run itself into the ground by 1974. In a valley, they went back to soul, were paired with producer Arif Mardin, and came up with an exquisite album called Mr. Natural, whose title track and lead single, “Charade,” were the best things they’d cut in years. They sounded contemporary again. For the follow-up, 1975’s Main Course, Mardin took them to Criteria Studios in Miami. Barry picked up the rhythm of the car wheels as they crossed a rickety bridge to the studio; transcribed, the rhythm became “Jive Talkin’,” their first number one in four years. Most significantly, Barry ad-libbed a falsetto while recording “Nights on Broadway.” Mardin’s ears pricked up—“Can you scream in tune?” he asked.

And with that question, Arif Mardin launched their second coming.

Five years of thrillingly urgent falsetto disco later, having crested the wave and crashed to the shore, they were unsalable. With no one buying records bearing the name “Bee Gees,” they decided to work undercover, cutting records with Jimmy Ruffin (“Hold On to My Love,” no. 10, ’80), Barbra Streisand (“Woman in Love,” no. 1, ’80), Dionne Warwick (“Heartbreaker,” no. 10, ’82), Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton (“Islands in the Stream,” no. 1, ’83), Diana Ross (“Chain Reaction,” no. 1, ’86). It was a pretty successful subterfuge.

Their fall had partly been their fault—by the time of Spirits Having Flown, their look (chest hair, teeth, medallions, teeth, horrid logo, more teeth) was preposterous and widely lampooned, and on “Tragedy” (a transatlantic no. 1 in ’79) there was none of “Night Fever” ’s subtlety or the emotional glide of 1975 single “Fanny (Be Tender with My Love)”; instead the Euro-bombast of acts like Boney M. was sneaking in. Still, Trevor Horn—soon to have his first number one with “Video Killed the Radio Star”—was probably taking notes. On the single’s flip side was something else entirely. “Until” is almost too heartbreaking to listen to; the antithesis of the A-side, it curls upward over Manhattan in a balloon built solely out of Aero-bubble keyboards and Barry’s orphaned vocal, gently drifting over the skyline and out of sight. It marked a farewell to their golden era.

By 1987, the dust had settled and the Bee Gees felt confident enough to make another record under their own name: “You Win Again”—which sounded like a Christmas carol created in a shipbuilding yard—was another UK number one. With this third breakthrough, the Bee Gees staked their claim as the most consistently successful and gently shapeshifting group of the modern pop era. When the most easygoing brother, Maurice, died in 2003, the group effectively ended. Through the nineties they had still scored the odd hit and their final, aptly titled, peek-over-the-shoulder single “This Is Where I Came In” reached the UK Top 20 in 2001. That’s thirty-four years of hits. No wonder they felt underappreciated.

Through it all, they were never fashionable. They made some diabolical mistakes, so bad that you’d think it was some kind of cosmic joke. Take “Fanny (Be Tender with My Love)”—no one else could have come up with such an ugly title (why not “Annie,” for God’s sake?) for such a beautiful song. Then there were the celluloid disasters. Saturday Night Fever, which grossed three hundred and fifty million dollars, was followed by a musical adaptation of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, a move so illogical (the Gibbs were famous for writing their own songs, and the Beatles were not exactly fashionable in post-punk ’79) it may have all been a dream—as with Barry and Maurice’s awful 1969 TV movie Cucumber Castle, Sgt. Pepper is buried so deep that even YouTube can’t find it. And here’s another Gibb peculiarity: they defined disco, yet released no twelve-inch singles until, paradoxically, their ill-advised rocker “He’s a Liar” in ’81.

Through it all, they were never fashionable. They made some diabolical mistakes, so bad that you’d think it was some kind of cosmic joke. Take “Fanny (Be Tender with My Love)”—no one else could have come up with such an ugly title (why not “Annie,” for God’s sake?) for such a beautiful song. Then there were the celluloid disasters. Saturday Night Fever, which grossed three hundred and fifty million dollars, was followed by a musical adaptation of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, a move so illogical (the Gibbs were famous for writing their own songs, and the Beatles were not exactly fashionable in post-punk ’79) it may have all been a dream—as with Barry and Maurice’s awful 1969 TV movie Cucumber Castle, Sgt. Pepper is buried so deep that even YouTube can’t find it. And here’s another Gibb peculiarity: they defined disco, yet released no twelve-inch singles until, paradoxically, their ill-advised rocker “He’s a Liar” in ’81.

None of this makes any sense until you remember their upbringing: cocooned, with extreme arrested development, they had no instincts for cool pop moves. With ill grace, they’d always point the finger when things went wrong, always be the first to build themselves up (on 1973’s Life in a Tin Can—“the best thing we’ve ever done, we think, and everyone who’s heard it agrees.” No, it was entirely unmemorable), or chide a fellow act in decline (Maurice on John and Yoko: “They say ‘power to the people’ but charge enormous prices for seats at their concerts”). Blaming anyone but themselves. Blaming it all on the nights on Broadway. They would walk out of interviews on a regular basis and, until the end, found it hard to understand their place in history after the almighty eighties backlash. So they were childish and childlike. Forgive them. They wrote a dozen of the finest songs of the twentieth century. The Bee Gees were children of the world.

Bob Stanley has worked as a music journalist, DJ, and record-label owner, and is the cofounder of the band Saint Etienne. He lives in London.

Excerpted from Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Story of Pop Music from Bill Haley to Beyoncé by Bob Stanley. Copyright © 2014, 2013 by Bob Stanley. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Origins of Kitsch, and Other News

Rosso Fiorentino, Madonna and Child with Four Saints (Spedalingo Altarpiece), 1518; image via the Nation.

Bill Gates’s favorite business book is 1969’s Business Adventures, “twelve classic tales from the worlds of Wall Street and the modern American corporation,” and “it’s easy to see why. Brooks, who wrote for [The New Yorker] for more than thirty years, approached business in an unusual way. He had an eye for the technical details that mattered to insiders, but the sensibility of a broad-minded cultural critic.”

“If you visit Florence this summer, you may find that ducking into the Palazzo Strozzi to see the remarkable exhibition ‘Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism’ (through July 20) is a great way to dodge the tourist crowds that choke the city’s streets. The works by these two Tuscans, who have good claim to being considered the originators of Mannerism, are as fascinating and problematic as ever. But chances are, if you’re inclined to look at them to discover affinities with art’s future, it’s not Matisse, German Expressionism, or Giacometti you’ll think of first. At least I didn’t—what I saw, for better or worse, was a postmodern Mannerism: the invention of bad taste or, as Clement Greenberg used to call it, kitsch.”

Talking to Jamie Keenan, a jacket designer: “Turd Theory (one of The Twenty Irrefutable Theories of Cover Design, written by myself and Jon Gray) works on the idea that in a scary world of disorder and chaos people are programmed to seek out repetition and order. So even the worst cover in the world, repeated twenty times in different colors of the rainbow, will get you an award or two.”

Some of literature’s greatest opening sentences—now in punch-card form.

Michael Oakeshott was one of the most original philosophers of the twentieth century, but also, his notebooks reveal, one of the strangest: “His response to the modern world was to cultivate an Epicurean gaiety and independence. (He rebuffed politely an approach by Margaret Thatcher, who had it in mind to recommend him as a Companion of Honour.) It was a style of life that combined seemingly antagonistic attitudes: a highly developed aesthetic sensitivity with a tolerance of everyday routine (he was punctilious when acting as chair of his LSE department); a capacity for intense romantic engagement with deep detachment.”

July 11, 2014

What We’re Loving: Boyhood, Blockbusters, Bay Area Ceramists

A publicity shot from Edge of Tomorrow.

“Left Coast/Third Coast”: it’s the name of an exhibition up at George Adams Gallery through the middle of next month, and a brilliantly concise epithet for those other places where art gets made. They refer, of course, to the West Coast and to Chicago, and the show focuses on artists whose careers were begun in the Bay Area and in the Windy City in the fifties and sixties. It’s not everyday you get to see so many of these artists in one place. Among them are Jim Nutt and Gladys Nilsson (part of the Hairy Who), Robert Arneson (a wonderfully profane Bay Area ceramist), and Jeremy Anderson (a West Coast sculptor who frequently worked with wood). H. C. Westermann’s work is also here, and it’s always a treat to see his sculptures and drawings in person. These are artists who not only returned to figuration when Abstract Expressionism was at its most monumental, but they did it in what were then considered remote corners of the country for art making. —Nicole Rudick

Go see Edge of Tomorrow, the new Tom Cruise sci-fi romp, and walk out about fifteen minutes before its rah-rah conclusion. What you’ll be left with—as three of us learned yesterday in an impromptu TPR Night at the Movies™—is a grim but heartening existential parable. If you’ve seen the ads, you know that Edge runs with a premise similar to Groundhog Day’s: Cruise plays an infantryman who comes back to life whenever he’s killed. Instead of awaking in sleepy Punxsutawney, he comes to in a militarized, bureaucratized hell, i.e., the future. He’s always hours away from facing a massive extraterrestrial invasion, and he’s always tasked (not unpleasantly) with seeking the counsel of Emily Blunt, who is always crouched in the same sweaty, imperious yoga pose. Cruise’s condition gives him a chance to defeat the aliens, but it also gives us a chance to watch him die, a lot, in an elaborate montage that’s as compelling as anything at the movies now. Step by painstaking step, he has to repeat an intricate performance on which the fate of humanity is staked. If you’re willing to dwell on the sequence, it can take you to some surprising places, some rarefied and some not: I thought of syllogisms, Sisyphus, The Trial, first-person shooters, cheat codes, mid-period Paul Verhoeven, D-Day, Dance Dance Revolution, Kierkegaard’s knight of infinite resignation, those team-building, problem-solving exercises I had to do in elementary school, and how neat it would be to save the planet with Emily Blunt. These ruminations may not bear fruit, but that’s okay—Edge is still a more enlightened mental vacation than it ought to be. —Dan Piepenbring

In trying to come up with recommendations for these posts, I sometimes think of Montaigne, who, despite serving as a legal counselor for most of his professional life, did not like giving advice: “I am very seldom consulted, and even more seldom heeded; and I know of no undertaking, public or private, that my advice has advanced and improved. Even those who, by chance, have come to depend on it, have in the end preferred to be guided by any other brain than mine.” He was a bit of a lone wolf, continuing, “By leaving me alone, they follow my declared wish, which is to be wholly self-reliant and self-contained. It pleases me not to be interested in the affairs of others, and to be free from responsibility for them.” This sentiment may have had something to do with the extreme social isolation in which Montaigne was raised; it was part of his father’s strict pedagogical curriculum, which would put today’s pre-Ivy prep Montessori schools to shame. (Montaigne’s first language—in sixteenth-century France—was Latin. Every morning the child was awakened by soft music. As a baby, he was sent to live with a peasant family for three years so he would not become accustomed to great wealth.) Montaigne later returned to this isolation, retreating to his tower-library in Dordogne when he retired. He considered the opinions of others “flies and specks that distract my will,” and so, at risk of being one of those specks, I recommend the vast, insight-laden Essays of this thoroughly, idiosyncratically educated man. They’re always worth another look. —Chantal McStay

Nearly a decade elapsed between each of Richard Linklater’s three Before Sunrise films, and like that trilogy, his latest, Boyhood, follows a pattern of real time, grounding us in fixed points throughout its character’s lives. Boyhood was filmed over twelve years, which allows its actors to age onscreen. It has an authenticity that’s too rare in cinema—its pinches of dialogue sound like natural exchanges, rooting the audience into a narrative that mirrors the adolescent experience with a painstaking awareness. Linklater recently voiced his intent in The New Yorker: “I always had that personality—I think it’s a writer’s sensibility—where you’re there but not there … I had to make a peace with myself. It’s like, well, you’re not in the moment. But just by contemplating it, by searching for the depth of the moment, that is itself an experience.” —Yasmin Roshanian

Solitary and Authentic Deep Readers

In his Art of Criticism interview from our Spring 1991 issue, Harold Bloom tells of a kind of literary conversion experience:

I was preadolescent, ten or eleven years old. I still remember the extraordinary delight, the extraordinary force that Crane and Blake brought to me—in particular Blake’s rhetoric in the longer poems—though I had no notion what they were about. I picked up a copy of the Collected Poems of Hart Crane in the Bronx Library. I still remember when I lit upon the page with the extraordinary trope, “O Thou steeled Cognizance whose leap commits / The agile precincts of the lark’s return.” I was just swept away by it, by the Marlovian rhetoric. I still have the flavor of that book in me. Indeed it’s the first book I ever owned. I begged my oldest sister to give it to me, and I still have the old black and gold edition she gave me for my birthday back in 1942. It’s up on the third floor. Why is it you can have that extraordinary experience (preadolescent in my case, as in so many other cases) of falling violently in love with great poetry … where you are moved by its power before you comprehend it? In some, a version of the poetical character is incarnated and in some like myself the answering voice is from the beginning that of the critic.

A few years later, in 2000, Bloom appeared on C-Span’s Booknotes in support of How to Read and Why. In the excerpt above, the host, Brian Lamb, gets him on the subject of teaching; and Bloom, who’s been a member of the Yale faculty since 1955, becomes visibly moved as he vacillates on the degree of isolation he feels:

Do I feel isolated in America? Yeah, I guess in a way I do. It does seem to me … I’m a somewhat outspoken old monster. You know, why not, at my age—what can they do to me? One wants to tell the truth. And I think the truth is pretty dreadful nowadays, culturally speaking and intellectually speaking … I guess I can feel kind of isolated. Isolated, maybe, in the profession. Isolated in terms of the media … But not isolated with the reading public … Clearly there are a vast number of what I would call solitary and authentic deep readers in the United States who have not gone the way of counterculture, and they are of all ages, and all races, and all ethnic groups.

And toward the end of the segment, as he blinks tears out of his eyes:

Here I am about to turn seventy and maybe I am obsolete, but that’s just personal inadequacy … What I hope to represent, what I try to represent, that cannot be obsolete. If that is obsolete, then we will go down. But I’m being too emotional. I’m sorry.

Bloom is eighty-four today, and still teaching. Happily his work is no closer to obsolescence than it was fourteen years ago.

The entire episode of Booknotes is available here.

Waiting for the Siren

A letter from Jerusalem.

Photo: Amir Farshad Ebrahimi, via Flickr

The rockets are back. It wasn’t two years ago they were falling over Israel. Things progress, they regress, they explode, and then you find yourself where you first began. With the rockets come all the accompanying nightmares about the endlessness of this war. We mutter darkly about escalation, look at pictures of the brutal deaths in Gaza. This is what comes when the rockets fall again. But the truth is, I missed them.

In Jerusalem or Tel Aviv, when the rocket siren goes off—a rising and falling pitch, kind of thin, actually—you have a recommended ninety seconds to find shelter. I use a method I’ve written about before to keep track of time: I sing Ghostface Killah’s “Run” to myself, as I run around the apartment looking for my boots. You’re supposed to go to a shelter or a safe room, if your building has one. If it doesn’t, as mine does not, you go to the stairwell, because it’s a reinforced area without much glass. Then you wait, nodding politely to four or so of your neighbors, whose names you still don’t know; smiling sympathetically at their children, who are posting fallout selfies.

The siren stops and you hear the booms of the rockets being detonated midflight by the Israeli defense system—the Iron Dome, love of my life—or hitting open areas that the anonymous geniuses manning the Iron Dome have determined to be okay to hit. They say to wait ten minutes, but nobody does. A few minutes after the booms, you all go back to your apartments, or step outside to catch a glimpse of the wispy, white puffs—all that remains of the rockets.

What I’d missed was the siren. The siren is always a moment away. I think about it all day, waiting for it to run up my spine. And when it comes, I feel a dark satisfaction, something akin to the satisfaction in recognizing a friend’s betrayal. I look forward to these moments as much as I fear them. Because what I crave, what I have learned to crave, are the few seconds of clarity that each siren brings. All day, every day, we labor over pointless decisions. When to eat, where to eat, how much. Answer or ignore this phone call? And this one? The banality of the day-to-day. But when you hear the siren, the world cracks open and everything is clear. You know the answer: find a safe place. There are no qualifications. I do not have time to consider that few people in Israel (as opposed to those in bleeding Gaza) have been hurt, that in Jerusalem (as opposed to the battered south), the rockets don’t hit, that ninety seconds (as opposed to fifteen in Ashkelon) is a fairly long amount of time to find cover. I only think about the answer: find a safe place. Things are falling from the sky. There is only an imperative.

On my way home from work, the siren went off. I froze for a few seconds and then ducked into the stairwell of a nearby building. There was a Russian Israeli woman, her two children, and someone’s grandma. After the siren and the booms—four—we said a standard, awkward goodbye: “Have a nice day, good luck.” Then we all hurried back into the late, fading daylight. The world we stepped into is gray and unclear. Boys murdered in tit-for-tat revenge. Babies buried under buildings in Gaza. Hamas is using human shields. Children in southern Israel cry under their desks. When I listen to those who are certain about what’s right for Israel to do, for Hamas to do, what’s the right way for the world to respond, I feel even more adrift. But for a horrific moment, everything was clear. We ran, we hid, we waited. As soon as it was over, I began to wait for it again.

Rebecca Sacks is a writer and graduate student at work on a book about being inside out in Israel.

What Silence Looks Like, and Other News

From 1916’s The Good Bad Man; image via The Atlantic.

Allan Ahlberg, a British author who’s written more than 150 children’s books, declined a lifetime-achievement award (and a nice cash prize) because Amazon sponsors it.

In the silent-film era, a movie’s typeface was a crucial part of its identity. Now, a type designer in Minneapolis has tried to re-create the font from The Good Bad Man, a Douglas Fairbanks vehicle from 1916. “In 1916 the titles would have been painted or drawn on a smooth surface and then photographed with the motion-picture camera. There were no optical printers in those days, so the titles would literally have been shot by someone hand cranking a motion-picture camera.”

In Athens, the Caryatid statues (five maidens “among the great divas of ancient Greece”) have emerged from a three-year cleaning with “their original ivory glow.”

“Movies, if they’re very good, aren’t a conversation; they’re an exaltation, a shuddering of one’s being, something deeply personal yet awesomely vast. That’s what criticism exists to capture. And it’s exactly what’s hard to talk about, what’s embarrassingly rhapsodic, what runs the risk of seeming odd, pretentious, or gaseous at a time of exacting intellectual discourse.”

A friendly reminder: your brain is on the brink of chaos.

July 10, 2014

Let’s Get Metaphysical

Argentina vs. the Netherlands, 1978: Argentina’s Mario Kempes of Argentina celebrates a goal.

Argentina and the Netherlands played yesterday’s second semifinal. That’s as much as should be said about the match, which forced us to appreciate what this World Cup has been while remembering what it could have been. Throughout 120 minutes of football, there was first, last, and above all an air of safety that had been refreshingly absent from most of the games thus far—and with that absence came gifts of goals and good play. But yesterday there was so much at stake: safe passage to a World Cup final. Since both teams are middling, professional, and graced by the presence of once-in-a-lifetime left-footed talents, they took no risks—no playing the ball patiently through the midfield, no attempts at a tactical surprise. It was a game of chicken, and a penalty kick shootout was the inevitable collision.

Or: Argentina and the Netherlands played yesterday’s second semifinal. That’s as much as should be said about the match, which forced us to rue what this World Cup could have been and to remember it exactly as it was. Throughout 120 minutes of football, there was an air of danger in every movement that put to sword the careless attacking and defending we’ve seen in all the games thus far—we’ve suffered own gifted goals and poor play for it. But yesterday there was so much at stake: safe passage to a World Cup final. Since both teams are fairly stout and battle-tested—graced by the presence of not only once-in-a-lifetime left-footed talents, but a host of other complimentary stars—they went forward intelligently instead of rashly. They avoided over-elaborating in the middle of the pitch and followed their tactical plans to the letter. It was as though the game was played in a labyrinth, and a penalty kick shootout was the inevitable way out.

Football games between sides with history between them seem to exist in a multiverse—everything that has happened between them happens here simultaneously. All outcomes exist at once. Hence, Argentina versus the Netherlands in the São Paulo of 2014 is Argentina versus the Netherlands in the Marseilles of 1998 is Argentina versus the Netherlands in the Buenos Aires of 1978. The weight of history is in the thickness of the air: young men run into each other with the anxiety and ache of memories that are not theirs, and the colors of their shirts become portals. No competition is barnacled by its past like a World Cup. Two sides significantly better than Brazil—but neither of which had ever defeated Brazil—capitulated in the round of sixteen and in the quarterfinals, more to the canary-yellow shirts than to the players who wore them. (We know what happened afterward.)

Hence, when we see a team or an individual rise above the history of all the encounters, all the simultaneity of events, what we’re really witnessing is something we see sadly infrequently: a personification of freedom. This weekend, Holland will play Brazil to avoid the distinct displeasure of finishing fourth, as in 1974 and 1994 and 1998, and Germany will face Argentina, as in the finals of 1986 and 1990. The latter was among the worst finals ever played. Let’s hope history doesn’t repeat itself.

Yesterday, as evening descended over a sullen São Paulo, no one was free. Not even Leo Messi and Arjen Robben, both of whom seemed born to dodge hurricanes in outhouses with the ball still stuck to their feet, could slip away from the moment. Everyone was there and not there. The Argentine coach, Alejandro Sabella, mainly stayed out of the way. The Dutch coach, Louis van Gaal, didn’t switch goalkeepers for the penalty shootout this time, or drastically change the formation mid-game. Each team had a defensive player offer a titanic, perhaps career-defining game: the Netherland’s Ron Vlaar and Argentina’s Javier Mascherano. Nothing and no one got past them. In the first half, Mascerano took a hit to the head and seemed to black out for a moment, but then he resumed playing again in a matter of minutes as if nothing had happened. Vlaar suffered no such injury. But in the absence of a willing volunteer among his more skillful teammates, he offered to take his team’s first penalty, and missed it.

Until that moment, the two men seemed mirror images of themselves in play and appearance. But that’s why the game has penalties. We can’t run forever. And we can’t live the same lives. Someone loses. And it’s written down.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s second book of poems, Heaven, will be published next year. He is the recipient of the 2013 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers