The Paris Review's Blog, page 680

July 25, 2014

The Best Medicine

Gerard van Honthorst, The Merry Fiddler, 1623

“He knew everything there was to know about literature, except how to enjoy it.” —Catch-22

Can a reader and a character be simultaneously amused? I’m sure plenty of really smart people have written about this—and maybe even answered it authoritatively—but I can’t find any such answer myself. I suppose the question also holds true for movies and TV—although arguably the blooper reel changes the entire conversation—but I’m chiefly interested in the question as it pertains to writing. I really want to know!

So far as I can tell, accounts of people being amused are never amusing. (In my opinion, this also holds true for most stories involving drug-induced antics—a scourge of modern storytelling—but I’m willing to admit this might be one of my “things.”) When a character “laughs,” “jokes,” “kids around,” “cracks up,” et cetera, it is not funny, even in an otherwise funny piece of writing. (Although, I think you’ll find in the funniest, characters don’t go around guffawing much.)

I’m not saying a character can’t laugh within something funny, but, rather, that their amusement is wholly divorced from the reader’s. It’s not just that human beings are sadists who, famously, enjoy watching the misfortunes of others; we all like to see beloved protagonists find love, get redeemed, generally achieve happy endings. Emotion is communicable. Laughter, maybe, isn’t. Or at any rate, the necessary distance imposed by narration makes the communication tricky.

Nothing is deadlier than writing about the workings of humor, so I’ll keep this short. If you can think of an exception to this, won’t you let me know? Am I just reading the wrong books? Has some author cracked this code? Or is this, maybe, just one of my “things?” Inquiring minds want to know.

Even the Losers

A drone—yes, really—photographed the action at our game against New York. Photo: Alon Sicherman, Center for the Study of the Drone

Even the losers

Keep a little bit of pride

—Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers

About a month ago, when I last wrote about The Paris Review’s softball team, I called us “damn fine.” “The Parisians are on something of a hot streak,” I had the gall to say, noting that we’d “met with defeat only once, at the hands of The Nation.”

Then July happened.

Reader, you gaze upon the words of a broken man. (Specifically a broken right fielder.) Today, that “damn fine” is inflected with callow hubris; that “hot streak” runs lukewarm. After three more games—against Vanity Fair, New York, and n+1—our season is over, and our win-loss record is a measly 4-4.

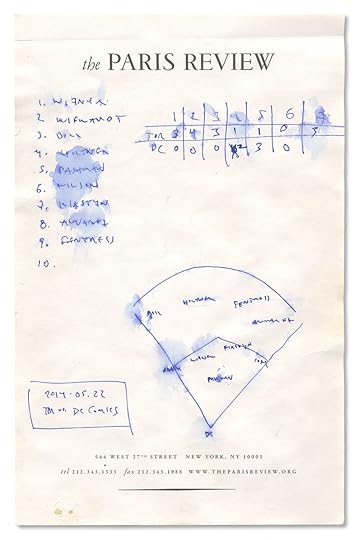

When we were good: the scorecard of this season’s first game, against DC Comics.

The close of yesterday’s game found us supine on the Astroturf, wondering: What happened back there? That’s for history to decide, or the trolls in the comments section. Whatever the case, our early, easy victories against the likes of The New Yorker and Harper’s now seem like distant memories.

The trouble started with our game against Vanity Fair, whose chic black-on-black uniforms belied their brutish athleticism. (And their trash talking: “Don’t just tweet about it,” shouted their third-base coach, “be about it.”) They eked out a 5-4 victory; I ate some of their pizza in recompense. Our spirits were still high enough, at that point, for a group photo:

After the loss to Vanity Fair, with our team mascot, Mischief II.

Alas, that loss was only a harbinger of the slaughter to come. Our next challenger was New York, and even though a TPR ringer brought a drone to the game—its photography can be seen above—our opponents were unruffled. They hit dinger after dinger; they even hit the scoreboard. We stopped counting their runs, eventually, and passed around a jar of whiskey and a box of donuts instead.

And then there was n+1, whose early homers gave them an insurmountable lead. This season’s MBP (Most Beleaguered Player) Award goes to our beloved Justin Alvarez, who faced derision yesterday for his faultless pitching. “I remember you,” an n+1 staffer told him at the bar after the game, when everyone was supposed to cultivate camaraderie. “You threw those weak pitches.” I mention this disgraceful behavior in the hope that n+1 will be shamed into kindness after future victories, should any occur.

So ends another summer of softball. To quote Bull Durham: “It’s a long season and you gotta trust it. I’ve tried ’em all, I really have, and the only church that truly feeds the soul, day in, day out, is the Church of [Beer-League Soft]ball.”

See you next summer on the diamond, everyone. We’ll bring the drone; you bring the heat.

5/22

TPR: 15

DC Comics: 5

6/1

TPR: 13

The New York Review of Books: 2

*featuring the first-ever Paris Review triple play

6/5

TPR: 8

The Nation: 15

6/24

TPR: 11

The New Yorker: 6

6/26

TPR: 16

Harper’s: 1

7/1

TPR: 4

Vanity Fair: 5

7/7

TPR: 5

New York: ∞

7/24

TPR: 4

n+1: 10

Sword-and-Sandal Epics Be Damned, and Other News

Poster for Atlas Against the Cyclops, 1961.

Movies set in Ancient Rome always do well at the box office. Why not Ancient Greece? “What is Hollywood to do with a world of 1,000 competing city-states, where homoeroticism was institutionalized and philosophers were more interested in the rationale for Platonic love than for war? … Greek tales would be better treated as supernatural thrillers. Imagine the real, lived historical experience for the ancient Greeks: the day-to-day jeopardy of knowing there was a fickle spirit in every breath of wind and ear of grain; that malicious deities might be lurking around the corner, shape-shifting to have their way with you.”

David Lynch, whose suspiciously mercantile interests I’ve complained about before, is now designing women’s luxury activewear. “The special collection features ‘limited edition David Lynch Floral’ print leggings, sports bras, shorts, and one very plain T-shirt, none of which are priced below $100.”

Why are so many cities building “innovation districts”? “Dozens of cities across the United States, Europe, South America, and East Asia are cultivating local utopias of entrepreneurship … These districts represent a mash-up of research institutions, corporations, start-ups, and business incubators, intermixed with ‘innovative housing,’ neighborhood amenities, and cultural sites in a clean energy, Wi-Fi-enabled environment … But is crowding a bunch of people into a few city blocks really the way to make creative sparks fly?”

Joan “Tiger” Morse “was a mod fashion designer in the mid 1960s … As the proprietress of the Teeny Weeny, her pop boutique located on Madison Avenue at 73rd Street, Morse sold mini dresses and other fashion oddities that used primarily man-made fabrications. With her frequent collaborator Diana Dew, Morse turned out illuminated mini dresses that would glow in myriad colors, all powered by a small battery pack worn at the waist.”

“The secret beating heart of the dream office is the stationery cupboard, the ideal kind, the one that opens to enough depth to allow you to walk in and close the door behind you. No one does close the door—it would be weird—but the perfect stationery cupboard is one in which you could be perfectly alone with floor-to-ceiling shelves laden with neat stacks of packets, piles and boxes, lined up, tidy, everything patiently waiting for you to take one from the top, or open the lid and grab a handful.”

July 24, 2014

Le Pater

In 1899, Alphonse Mucha, a progenitor of Art Nouveau, published Le Pater, an illustrated edition of the Lord’s Prayer embellished in his sinuous, faintly occult style. Mucha, who was born today in 1860, made only 510 copies of the book, which he considered his masterwork. According to the Mucha Foundation,

Mucha conceived this project at a turning point in his career … [he] was at that time increasingly dissatisfied with unending commercial commissions and was longing for an artistic work with a more elevated mission. He was also influenced by his long-standing interest in Spiritualism since the early 1890s and, above all, by Masonic philosophy … the pursuit of a deeper Truth beyond the visible world. Through his spiritual journey Mucha came to believe that the three virtues—Beauty, Truth and Love—were the ‘cornerstones’ of humanity and that the dissemination of this message through his art would contribute towards the improvement of human life and, eventually, the progress of mankind.

Whether or not you buy into his spiritual ambition—and I must admit that I don’t—Mucha’s illustrations are striking in their depth and detail, with a certain haunted, diaphanous quality that would be imitated, if never duplicated, throughout the twentieth century, right on up to those ponderous Led Zeppelin “Stairway to Heaven” black-light posters that continue to grace all too many dorm rooms. As the artist Alan Carroll explains,

in the 1870s and 1880s, so many American artists went to study in Paris (e.g. Sargent, Whistler, Cassatt, Eakins, Homer) because American academic training at the time was generally considered so inadequate. Combine this with a mesmeric American fascination with the Old World, and we can begin to see why Mucha’s early trips to the States were so rapturously received. And yet Mucha seemed reluctant to lap up the attention that the gentry and grandes dames of American Society were determined to bestow. Indeed, he was sick and tired of his obligations, as evidenced in a hilariously melodramatic letter he wrote in 1904: “You’ve no idea how often I am crushed almost to blood by the cogwheels of this life, by this torrent which has got hold of me, robbing me of my time and forcing me to do things that are so alien to those I dream about.”

Something of that crushed-to-blood quality comes through in Le Pater, whose fascination with the otherworldly is predicated on a kind of desperation: There must be something more, right?

You can see more of Le Pater at Carroll’s blog, Surface Fragments.

Genius of Love

Photo: Rob Boudon

Somewhere in the world there exists a clip of Hugh Hefner on one talk show or another. I can neither remember what the show was nor the exact wording of the exchange, but the following paraphrase has become legendary in my family:

INTERVIEWER: Do you consider yourself a genius?

HEFNER: Genius is a difficult word to define. But by any definition, I am one.

Hef may be a law unto himself, but genius, a word that used to be the sole domain of the upper reaches of the IQ scale, is now thrown around like grass seed. Maybe it’s the effect of language evolution or intelligence inflation—after all, only recently has it became compulsory for one’s child to be intellectually gifted—but it can’t be denied that genius no longer packs the awe-inspiring punch it once did.

Standing in line at the nearest Apple Store yesterday, I couldn’t help but wonder: Do the various professional Geniuses there find their appellation hilarious? Do they joke about it all the time? Or are some jokes—in the words of Doris Day in Pillow Talk—too obvious to be funny? One thing I did notice: the people working the Genius Bar all seemed to get along really well. It was like the most collegial workplace I’d ever seen. Maybe because they’re all on the same intellectual level, and engaged in the same enterprise, obscure to much of humanity. Did everyone get along so well on the Manhattan Project?

To me, the workings of a computer are so mysterious, so frightening, that the easy competence with which the Geniuses handle all problems might as well be rocket science. When a very pleasant Genius named Jamie diagnosed the problem that had been sucking up space on my hard drive, opening up some fourteen new gigabytes, I suddenly understood why vulnerable women are always falling for their surgeons and spiritual leaders: in that moment, I was completely in love with him. I found myself wishing that I had put on some mascara, and had not—in deference to the muggy heat—dressed in a free-flowing cotton dress reminiscent of my mother circa summer ’84. (In summer ’84, bear in mind, my mother was pregnant.) I also wished I didn’t have a picture of Susan Sontag in a bear costume on my desktop.

When I signed the electronic screen at the end of my appointment, I attempted to redeem myself by asking what I hoped was an intelligent question: If we all write like five-year-olds on these screens, how is the signature any deterrent to identity theft?

Well, he said, it could all be checked against records—the signature itself is not the point. “Some people will even sign an X,” he explained.

“Like medieval illiterates?” I asked excitedly. And for the first time, the Genius’s face bore the same look of total, bored incomprehension I’d been sporting since I entered the air-conditioned confines of the Apple Store.

Lost in Music

Musical mind control from Mesmer to the Satanic panic.

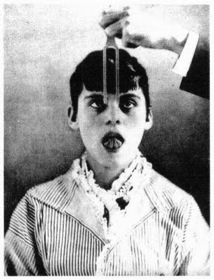

A hysterical patient in a catatonic fit, supposedly caused by the huge tuning fork. Désiré Magloire Bourneville and Paul Regnard, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (1876–1880).

To lose oneself in music is generally regarded as a good thing—an ecstatic experience, or at least an absent-minded pleasure. But despite the Eminems, Daft Punks, and Sister Sledges of the world, Western culture has often had niggling fears about letting go in that way. What if the music can make you do things? What if surrendering to it means surrendering the parts of yourself that hold you back from madness, adultery, and murder? What if heavy metal sends teens on killing sprees? What if rock and roll makes girls shed their sexual inhibitions, causing a rash of nymphomania and pregnancy and the collapse of social order—or what if it can whip crowds into a malleable frenzy, leaving them the pitiful stooges of Communist or other sinister causes? What if it can be used with other forms of thought control to turn people into Manchurian Candidate–style automatons?

The fear, however implausible, that music has mysterious powers—that it can hypnotize or brainwash, making us the playthings of malign manipulators or our own dark instincts—has crept into the public discourse surprisingly often over the past two hundred years. Concerns about the medical, sexual, social, and political consequences of musical hypnosis are an essentially modern business; until the eighteenth century, trance states were often seen in a positive light, even as a way of connecting to the divine. But against the background of the internalized self-control demanded by modern urban society, trance states have been increasingly regarded as pathological symptoms—something to be explained by doctors, not priests.

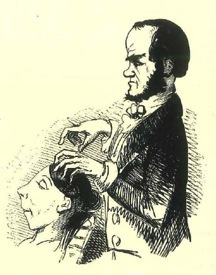

The ambiguous, picaresque career of Franz Anton Mesmer, the pioneer from the 1770s of Animal Magnetism and its associated hypnotic techniques, epitomized this trend, recasting trance in a semi-occult medical context.He and his followers often used music in their treatments, favoring in particular the ethereal and uncanny sound of the glass armonica, which uses friction to produce tones in a series of graduated glass bowls. Along with many other aspects of Mesmerism, this musical element often provoked a titillated fascination as well as skepticism and mockery. Many of the themes that dominate the debate on musical hypnotism have their origins in discussions and satirical depictions of Mesmerism, especially the sense that the entranced person—often a woman—was open to the sexual manipulation of the magnétiseur who put her there. In 1790, the English Quaker A. Fothergill suggested that the impact of the “magnetic professor” on “delicate females of fine feelings and susceptible nerves” was to stimulate “their passions to the highest pitch … till the wished-for crisis comes,” like a bridegroom.

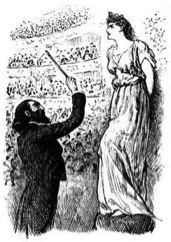

The English Mesmerist and phrenologist John Elliotson manipulating a young woman, playing her head like a piano.

The same kind of fears about sex and mind control recurred in the Paris of the 1870s, when the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot conducted the most systematic work on sound and hypnosis in the nineteenth century. Charcot and his colleagues apparently created hypnotic and indeed catatonic fits among their female hysterical patients by using gongs, gigantic tuning forks, and even children’s lullabies. Charcot regarded these trance states as expressions of a semi-epileptic neurological condition, akin to the reflex action that makes a patient kick when hit on the knee with a doctor’s hammer. Although modern medicine does recognize “musicogenic epilepsy”—in which music, even specific songs (such as, according to one study, Mariah Carey’s “Dream Lover”) provokes epileptic fits—it’s likely that Charcot’s striking and vividly photogenic results were the consequence of suggestion and straightforward simulation by the women concerned. There was a strong theatrical and implicitly voyeuristic character to these experiments, with the women involved becoming minor celebrities in Paris after they were shown off to the public. Beyond Paris, the reaction to these experiments often focused on the sexual dangers involved. A character in Tolstoy’s strange 1889 novella, The Kreutzer Sonata, calls for the state control of music to prevent magnétiseurs from hypnotizing women with immoral purposes in mind. The American psychologist Aldred Warthin had been told of cases of spontaneous orgasm among Wagner fans hypnotized by the music, but in an 1894 article he regretted to announce that his attempts to replicate these results had not been successful.

Another hysterical patient, supposedly experiencing an automatic reflex caused by the tuning fork, forcing out her tongue. Paul Richer, Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière (1889).

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the concept of hypnotic music faded as hypnosis came to be seen as a matter of suggestion rather than a neurological reflex. But in the fifties, it made a rather sudden comeback amid the panic about brainwashing. Although the concept has roots in Chinese thought, its modern sense dates from the Korean War—when Communists had apparent success in converting American POWs to their cause, the CIA alleged that the troops were the victims of a mind-control campaign. The agency began to invest serious money in the so-called MK-ULTRA program to see if they could achieve similar effects themselves. Much of their research drew on Ivan Pavlov’s work with learned or conditioned reflexes—work that also employed tuning forks, metronomes, and whistles. The English psychiatrist and Pavlovian William Sargant became a leading authority on the power of music to brainwash; he wrote that Beatlemania was a dangerous possession cult and suggested to Newsweek that Patty Hearst had been turned from a kidnapping victim to an armed robber by having been forced to listen to rock music.

The idea of musical brainwashing had considerable resonance in this period. Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film adaptation both depict the fictional “Ludovico Technique,” a form of aversion therapy that involves “very like sinister” music, reaching a climax in a scene in which images of Nazi atrocities are played against the music of Alex’s favorite composer, Beethoven. (Alex himself expresses some skepticism about music’s civilizing effect—“Civilized my syphilized yarbles,” he exclaims. “Music always sort of sharpened me up.”) American conservative evangelicals were quick to adopt the idea of musical brainwashing as an explanation for what was happening to the young people of their country. In books like 1966’s Rhythm, Riots and Revolution, David Noebel, long part of Billy James Hargis’s segregationist Christian Crusade, argued that sixties rock ‘n’ roll was literally a Kremlin plot. “If the following scientific program is not exposed,” he warned, “degenerated Americans will indeed raise the Communist flag over their own nation.” He provided ingenious if paradoxical reasoning to explain why Communist states banned rock music, even though it was their own sinister invention—it just showed that they knew how dangerous it really was!

Alex being forced to see violent images and hear music as part of the “Ludovico Technique” in Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange.

In the Reagan era, the anxiety about musical brainwashing shifted onto another supposed worldwide conspiracy—Satanism. The eighties and nineties in America saw a full-scale moral panic that linked the “science” of brainwashing to a supernatural satanic threat emanating from heavy metal music. A wide range of books with titles like The Devil’s Disciples, Rock’s Hidden Persuader, and (my personal favorite) Hit Rock’s Bottom spread the word that certain bands were brainwashing innocent teenagers with subliminal messages to lure them into the worship of the devil, sexual immorality, murder, and especially suicide. Such was the panic that the Parents’ Music Resource Center sold a fifteen-dollar “Satanism Research Packet.” Much of the anxiety focused on the supposed ability of messages recorded backward (so-called backmasking) to influence listeners subliminally. “Experts” often disagreed about what the backward message actually was. A well-known preacher in Ohio publicly burned a recording of the theme song to Mister Ed because he said it contained the lyric “Someone sing this song for Satan” when played backward.

“Beatle possession.” William Sargant, The Mind Possessed (1973).

The backmasking scare really took off when it was used to link heavy metal to the rise in teen suicide, even though songs about suicide were by no means a new phenomenon. In 1985, Ozzy Osbourne faced a lawsuit based on the accusation that his song “Suicide Solution” had brainwashed a nineteen-year-old into attempting suicide. The case was thrown out on freedom of speech grounds, but the idea of “subliminal” backmasking appeared to offer a way around First Amendment protections. The parents of two teenagers who shot themselves in 1985 blamed Judas Priest, claiming that “satanic incantations are revealed when the music is played backwards.” Their expert witness (a marine biologist—I’m not making this up) said he could make out the words “do it” when the song was played in reverse. The case was unsuccessful, but the idea of metal as a form of potentially lethal brainwashing entered the public imagination. After Richard Kuntz killed himself while listening to Marilyn Manson in 1996, his father testified before a U.S. Senate Committee, arguing that musical brainwashing was responsible; several media reports blamed Manson for the Columbine school massacre in 1999.

Though it’s proved very popular in these various contexts, it should go without saying that the whole idea of musical hypnosis or brainwashing is fundamentally bogus. Music can play a limited role in the creation of trance states, but it certainly doesn’t work in the automatic way theorized—or willed—by those who have been most concerned about its dangers. In any case, there’s little to suggest that we can be hypnotized against our will, let alone without our knowledge; people can be manipulated, of course, in all sorts of ways, but the evidence from the Korean War and elsewhere is that it old-fashioned fear and violence are most apt to change behavior. Likewise, the notion of subliminal messages subtly brainwashing impressionable youths is highly questionable. Weak stimulus in fact has a weak effect, and that backward messages have been shown to have no effect at all.

The sinister anti-Semitic caricature Svengali uses hypnotic tricks to make the innocent Aryan Trilby a great singer and to marry her. George du Maurier, Trilby (1894).

The debate surrounding musical brainwashing has never really been about music at all: it’s about sex, self control, and social order. For a certain kind of social conservative, it’s always tempting to construe other people as the marionettes of agitators or our basest, most primitive instincts. The directly physical effect of music, its ability to make listeners’ bodies literally resonate, giving rein to their own impulses and potential group dynamics, can always put it at odds with ideals of discipline, making it an especially adept vehicle for some of society’s deepest anxieties. Music certainly can change behavior. It can increase sales in a shopping mall, but it can’t make you someone else’s puppet.

Dr. James Kennaway is a Historian of Medicine at Newcastle University. He has previously worked at Oxford, Stanford and Vienna. His book Bad Vibrations: The History of the Idea of Music as a Cause of Disease was published in 2012.

Witchcraft Then and Now, and Other News

Detail from Francisco José de Goya’s Linda maestra, 1797.

Profiling William T. Vollmann: “Although Vollmann these days sports the punctilious mustache of a maître d’, he still resembles the baby-faced boy wonder readers first encountered in his shocking late ’80s author photo, in which he affectlessly held a pistol to his own head … Along with the Internet and e-mail, Vollmann also foregoes cell phones, credit-card use, checking accounts, and driving.”

On David Mitchell’s Twitter story, “The Right Sort”: “The effect of reading was not feelings of disjunction and separation but rather one of surprising connection, a sense of disappearing into the scroll and the vortex of the story.”

From the Guardian, July 24, 1844: “a most lamentable difference exists between the witchcraft of modern romance and the witchcraft of ancient superstition.”

“Is there any consistent relationship between a book’s quality and its sales? Or again between the press and critics’ response to a work and its sales? … As of a few days ago UK sales of all three volumes of Knausgaard work in hardback and paperback had barely topped 22,000 copies … In the US, which has a much larger market, that figure— total sales of all three volumes (minus e-books)—stood at about 32,000.”

“As Amazon gains market share, we can no longer abide its self-proclaimed conceit that unfettered growth is invariably in the consumers’ interest … Amazon ought no longer to be permitted to behave like a parasite that hollows out its host. A serious Justice Department investigation is past due.”

July 23, 2014

Bayou Medicine

The swamp doctor also stabs bears, apparently.

Given the ungodly humidity, today seems as good a day as any to peruse an 1858 volume whose full title is The Swamp Doctor’s Adventures in the South-West; Containing the Whole of The Louisiana Swamp Doctor; Streaks Of Squatter Life; and Far-Western Scenes; in a Series Of Forty-Two Humorous Southern And Western Sketches, Descriptive Of Incidents And Character, by John Robb (“Madison Tensas, M.D.” and “Solitaire”) author of “Swallowing Oysters Alive, etc.”

Oh, the glories of the public domain! Here’s a sordid bit from a chapter called “The Mississippi Patent Plan for Pulling Teeth”:

I had just finished the last volume of Wistar’s Anatomy, well nigh coming to a period myself with weariness at the same time, and with feet well braced up on the mantel-piece, was lazily surveying the closed volume which lay on my lap, when a hurried step in the front gallery aroused me from the revery into which I was fast sinking.

Turning my head as the office door opened, my eyes fell on the well-developed proportions of a huge flatboatsman who entered the room wearing a countenance, the expression of which would seem to indicate that he had just gone into the vinegar manufacture with a fine promise of success.

“Do you pull teeth, young one?” said he to me.

“Yes, and noses too,” replied I, fingering my slender moustache, highly indignant at the juvenile appellation, and bristling up by the side of the huge Kentuckian, till I looked as large as a thumb-lancet by the side of an amputating knife.

“You needn’t get riled, young doc, I meant no insult, sarten, for my teeth are too sore to ‘low your boots to jar’ them as I swallered you down. I want a tooth pulled, can you manage the job? Ouch! criminy, but it hurts!”

“Yes, sir, I can pull your tooth. Is it an incisor, or a dens sapientiæ? one of the decidua, or a permanent grinder?”

“It’s a sizer, I reckon. It’s the largest tooth in my jaw, anyhow, you can see for yourself,” and the Kentuckian opening the lower half of his face, disclosed a set of teeth that clearly showed that his half of the alligator lay above …

Everything being ready, we invited the subject to take his seat in the operating chair, telling him it was necessary, agreeably to our mode of pulling teeth, that the body and arms should be perfectly quiet; that other doctors, who hadn’t bought the right to use the ‘patent plan,’ used the pullikins, whilst I operated with the pulleys. I soon had him immoveably strapped to the chair, hand and foot. Introducing the hand-vice in his mouth, which, fortunately for me, was a large one, I screwed it fast to the offending tooth, then connecting it with the first cord of the pulleys and intrusting it to the hands of two experienced assistants, I was ready to commence the extraction. Giving the word, and singing, “Lord, receive this sinner’s soul,” we pulled slowly, so as to let the full strain come on the neck bones gradually.

Though I live till every hair on my head is as hollow as a dry skull, I shall never forget the scene.

Clothed in homespun of the copperas hue, impotent to help himself, his body immoveably fixed to the chair, his neck gradually extending itself, like a terrapin’s emerging from its shell, his eyes twice their natural size, and projected nearly out of their sockets, his mouth widely distended, with the vice hidden in its cavity, and the connexion of the rope being behind his cheeks, giving the appearance as if we had cast anchor in his stomach, and were heaving it slowly home, sat the Kentuckian, screaming and cursing that we were pulling his head off without moving the tooth, and that the torment was awful. But I coolly told him ‘twas the usual way the ‘Mississippi patent plan’ worked, and directed my assistants to keep up their steady pull.

I have not yet fully determined, as it was the first and last experiment, which would have come first, his head or the tooth, for all at once the rope gave way, precipitating, without much order or arrangement, the assistants into the opposite corner of the room.

The operating chair not being as securely screwed down as usual, was uptorn by the shock of the retrograde motion acquired, when the rope broke, and landed the Kentuckian on his back in the most distant side of the room; as he fell, he struck the side of his face against the wall, and out came the vice, with a large tooth in its fangs. He raged like one of his indigenous thunderstorms, and demanded to be released. Fearing some hostile demonstration when the straps were unfastened, we took occasion to cut them with a long bowie knife. He rose up, spitting blood and shaking himself, as if he was anxious to get rid of his clothes. “H—l, Doc, but she’s a buster! I never seed such a tooth. I recon no common fixments would have fotch it; but I tell you, sirree, it hurt awful; I think it’s the last time the ‘Mississippi Patent Plan’ gets me in its holt. Here’s a five-dollar Kaintuck bill, take your pay and gin us the change.”

Seeing he was in such good humour, I should have spared him, but his meanness disgusted me, and I thought I would carry the joke a little further. On examining his mouth, I suddenly discovered, as was the case, that I had pulled the wrong tooth, but I never told him, and he had too much blood in his mouth to discover it.

“Curse the luck,” I exclaimed, “by Jupiter I have lost my bet. I didn’t break the infernal thing.”

“Lost what?” inquired the patient, alternately spitting out blood, and cramming in my tobacco.

“Why, a fine hat. I bet the old boss that the first tooth I pulled on my ‘Mississippi Patent Plan,’ I either broke the neck of the patient or his jaw-bone, and I have done neither.”

“Did you never pull a tooth that way before? why, you told me you’d pulled a hundred.”

“Yes, but they all belonged to dead men.”

“And if the rope hadn’t guv way, I reckon there’d bin another dead man’s pulled. Cuss you, you’d never pulled my tooth if I hadn’t thought you had plenty of ‘sperience; but gin me my change, I wants to be gwine to the boat.”

I gave the fellow his change for the five-dollar bill, deducting the quarter, and the next day, when endeavouring to pass it, I found we had both made a mistake. I had pulled the wrong tooth, and he had given me a counterfeit bill.

Should the spirit move you—and why wouldn’t it?—you can read more of the good doctor’s dubiously hygienic exploits here.

Bittersweet

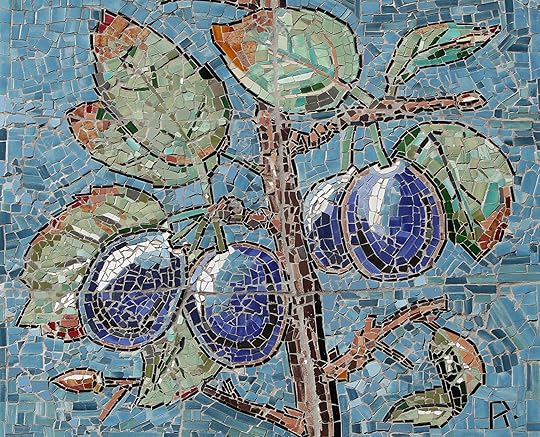

Richard Ruepp, Plums, 1953-4

One might wonder at the wisdom of undertaking a batch of homemade jam on a ninety-degree day. But I think about it this way: when people actually canned fresh food to get through the winter, it all happened in the summer; hot weather is when you’re supposed to stand over a kettle stirring incessantly without air conditioning.

Besides, I’ve recently come into a very large—tyrannically bountiful—number of plums, the result of a CSA share lent to me by some generous friends. Their family of four can eat a lot more fresh fruit than one smallish woman living alone. And although there are probably lots of things I could do with them, in my family there is a tradition of plum-jam-making.

Well, sort of. Plum jam was one of my grandfather’s specialties, along with the strips of discounted meat he prepared in his smoker, the icy “gelato” we made in the “electric” ice-cream maker (it was broken, and had to be cranked by hand), and the increasingly dubious loaves that came out of a yard-sale bread machine. While no one can fault the man’s zeal, his technique was, to say the least, idiosyncratic.

Because the plum tree in the backyard—overlooking a rubble pile, an old boat filled with pressure cookers, and a trailer—yielded a large crop of deliciously sweet, red fruit, there were always several spontaneous bouts of jam-making during our summer visits. For us children, that meant gathering the fallen plums off the ground. Later, we got to plunge our (unwashed) hands into the cooled, cooked (but unwashed) plums, and squeeze them to a pulp. My grandfather did not believe in what he termed “the germ theory.”

The resulting jam—unrefrigerated, it goes without saying, and not processed for sanitary storage—was beautiful to behold, but it was so tart that most of us found it inedible. My grandfather, however, feasted on it every morning, and would frequently shove a piece of jammy toast into our faces. “Plum jam!” he’d bark. “Taste it! It’s excellent!”

There is a picture of me and three younger cousins sitting on the roof of a shed under the plum tree in full fruit. Now my grandfather is long gone, and the branches of the family have fractured and ruptured in the sad way that families can. But there’s not a single one of us who would hear the words “plum jam” without knowing they were shorthand for about a million more, sweet and sour both. I am washing my hands and my plums, and I plan to add a good measure of sugar to my batch of jam. But the whole thing is a terrible, impractical idea, and that seems in the family spirit.

Regina and Louise

A companion to yesterday’s piece by Edgar Oliver.

Regina Bartkoff

Louise Oliver

Regina Bartkoff

Louise Oliver

Regina Bartkoff

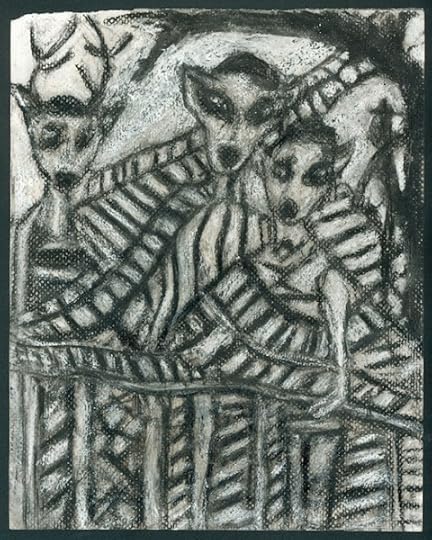

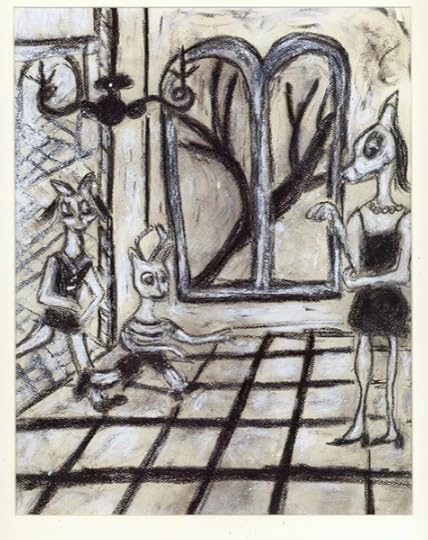

For a long time, whenever I visited Edgar Oliver on East Tenth Street, I would look at his mother’s wonderful paintings. They hung all over his crumbly walls and because it was always night when I visited, they were amber lit from the lamps sitting here and there in Edgar’s living room. Whenever I looked at the paintings, I would feel a pang at the thought that I’d never get to meet her. When I decided that I wanted to make Louise Oliver the subject of the third issue of my magazine, Housedeer, Edgar brought out portfolios filled with her drawings for me to see and we looked at them together, sitting on the floor. It seemed as though his whole childhood, and his sister Helen’s too, had been recorded in pencil by Louise. She must have drawn her children constantly, and she drew cemeteries and swamps and old houses and churches and ordinary people going about their business on the streets of Savannah, where they lived. Many of her drawings included detailed notes to herself on the colors of everything in them, so she could use them later to make paintings. Edgar told me that he and Helen were raised to be artists.

I wanted to ask Regina Bartkoff to do a drawing for Louise’s Housedeer cover because while she and Louise have very different styles, there is something about each of them that reminds me of the other. To my eye, the beauty of Regina’s drawings is in their mystery and their innocence. And I think if I had to choose one word to describe what Regina and Louise have in common in what they’ve made, the word innocent might be a good one. Honest would be another. When I told Regina what I wanted, it had been more than a year since she had done any drawing at all, the reason being that she and her husband, Charles Schick, had just finished doing a play by Tennessee Williams called In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel. The play was put on in the gallery they have use of on East Third Street, and they had not yet come out of that other world. Regina and Charles love theater and they love painting (Regina loves drawing too), but when they do a play, it is all-consuming. Regina was still waking up as Miriam, her character in the play, and feeling the kind of lost that theater people often feel when the play is over.

Regina and Charles both knew Edgar Oliver, but they had never seen Louise’s paintings, so one night we all went together to visit him. Regina and Charles stood before each painting, in awe, just looking. Edgar read a story plot aloud to us that Louise had written in a little notebook once, about a farmer named Elijah Gribbins who secretly longed to visit the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. When he eventually managed to get there, Louise described it: “Well, here was Elijah, face to face with Rembrandts, Vermeers, Constables, Turners, Picassos, Matisses. All the greats had been getting the once-over. His joy was almost unbearable.”

Soon after the evening at Edgar’s, drawings from Regina started coming to me via e-mail, one after another. I had asked her for deer—each Housedeer cover comes from a different artist; anything they want to make, as long as a deer is somewhere in there—and I liked every drawing she made. But the rendering of Edgar, Louise, and Helen as three beautiful deer was unmistakably the perfect one.

Regina isn’t someone who usually makes work to order, and she told me that at first the deer drawings felt very stiff to her. She said she had realized, too, that she and Louise had the exact opposite way of working. “Louise would go out and look at things and she was a very skillful draftsman,” Regina said. “My drawings come out of my subconscious and I’m not a trained draftsman. But when you were liking the drawings I sent, that gave me a little bit of confidence and all of a sudden the drawing started to become more subconscious. I wasn’t just drawing Edgar Oliver’s family. The drawings started to feel like mine again.”

This essay is adapted from a longer piece in The Folio Club 's drawing issue.

Romy Ashby is the author of The Cutmouth Lady, the creator of Housedeer magazine, and a songwriter on the Blondie albums No Exit and The Curse of Blondie. In early 2014 she directed Charles Schick and Regina Bartkoff in a critically acclaimed independent production of Tennessee Williams’s The Two-Character Play.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers