The Paris Review's Blog, page 683

July 17, 2014

The Decline and Fall of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, and Other News

Kirsten Dunst, the original MPDG, in 2005’s Elizabethtown.

A new project, “The Archaeology of Reading in Early Modern Europe,” catalogs and digitizes marginalia from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. “These notes reveal a largely unvarnished history of personal reading within the early modern historical moment. They also embody an active tradition of physically mapping and personalizing knowledge upon the printed page.”

How will Woody Allen’s latest film fare in light of the allegations leveled against him earlier this year? “Allen dismissed the possibility that lingering outrage could affect the public’s interest in Magic in the Moonlight. ‘No thoughts like that occur to me … They only occur to you guys,’ ” said Allen, who, as coincidence would have it, is referred to as a “major-league fantasist” elsewhere in this piece.

Nathan Rabin has apologized for inventing the phrase “Manic Pixie Dream Girl”: “I’m sorry for creating this unstoppable monster. Seven years after I typed that fateful phrase, I’d like to join Kazan and Green in calling for the death of the ‘Patriarchal Lie’ of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope. I would welcome its erasure from public discourse.”

The art collector George Costakis devoted his life “to unearthing masterworks of the Russian avant-garde … but his enthusiasm met with obstacles: the difficulty of tracking down the works, the neglect they had suffered, the disbelief of widows (‘What do you see in them?’). In a dacha outside Moscow he found a Constructivist masterpiece being used to close up a window; the owner wouldn’t part with it. He dashed to the city to fetch a piece of plywood the same size, ferried it back to the dacha, and swapped it for the painting.”

“The history of punk is, above all, the story of the traumatic loss of its elusive essence: that brief moment in time when a new sensibility was beginning to coalesce … Punk died as soon as it ceased being a cult with no name.”

July 16, 2014

The Golden West: An Interview with Daniel Fuchs

Doris Day and James Cagney in Love Me or Leave Me, for which Daniel Fuchs wrote the screenplay.

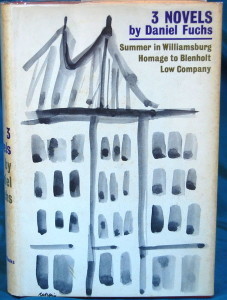

In early 1989, I telephoned Daniel Fuchs (1909–‘93), then in his eightieth year, in Los Angeles to ask about the possibility of interviewing him for The Paris Review. The novelist and screenwriter—heralded for his Williamsburg Trilogy of the 1930s (Summer in Williamsburg, Homage to Blenholt, and Low Company) and Love Me or Leave Me, for which he won an Academy Award—was cordial and open, but stipulated that he preferred to have the questions sent to him; he would mail back his answers. I sent the questions, twenty-seven of them, to Fuchs that February, and at first there appeared to be clear sailing—the writer said he would soon have something.

At the same time, Fuchs expressed a concern about the handling of the copyright when the interview was printed, and over the next several weeks it became increasingly difficult to allay or understand his fears. Although I’d assured him the rights would revert immediately to him upon publication, he remained concerned, asking for a signed warranty from George Plimpton. When this wasn’t quickly sent—owing to office delays rather than any disinclination—the writer grew vehement, and then abusive. Reluctantly I let go of the idea of seeing through an interview with Fuchs, whose work remains too much of a secret to this day.

A year or so after Fuch’s death in 1995, having been informed that the writer’s papers were in Special Collections at the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University, I phoned Dr. Howard Gotlieb, the Special Collections librarian, to ask if, by any chance, there was an interview circa 1989 among the papers. Indeed there was. Fuchs had constructed an interview that, while based on my questions, departs from them in unexpected and telling ways. It amounts to a late work by the distinguished, if unexpectedly irascible, “magician,” as John Updike once pronounced him.

You have been identified by Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, and others as one of three Jewish novelists of the 1930s whose work has survived a half century now, the other two being Henry Roth and Nathanael West. Would you comment on the literary climate of the thirties?

Survived, rediscovered—a peculiar occurrence. A man sits in a room writing novels. Nothing happens. The books don’t sell—four hundred apiece, the last one a few more. There are scattered reviews. Then thirty years later, suddenly, the books are brought out, again and again, acclaimed. A small-sized mystery. Of course, I’m talking only of my own books. Call It Sleep and Nathanael West’s work attracted attention from the start and were well known all along.

Did you read Call It Sleep when it came out?

With pleasure and pangs of jealousy.

Nathaniel West went to Hollywood and wrote B movies and worked on his last novel, The Day of the Locust, which in its final sentence seems to indicate that the protagonist has succumbed to the furies around him in Hollywood and gone mad. Henry Roth moved to rural Maine and hasn’t, as of now, published another novel. You gave up a literary career for several decades to write movies. Is there a common thread in all this?

No, I don’t think so. West kept working on his own material up to the end, while he was doing the pictures at Republic. Roth had his own reasons. I liked it in Hollywood and stayed on. I found the life most agreeable. Mordecai Richler went out of his way, in a book review, to say I bragged about the money I made in Hollywood. Actually, I never made a great deal of money in the movies. Sixty thousand dollars a year was about the best I could do, if Richler doesn’t mind my saying so. In fact, I went nearly broke, had to sell my house, and then an amazing thing happened, another one of those mysteries. A benefactor, a character out of a Molnár play—I can’t say his name, he once asked me never to bother him or intrude—stepped forward. He’s been watching out for us over the past number of years and we’re quite comfortable. I guess I mention all this to get a rise out of Richler. Hollywood strikes a nerve in some people.

If Summer in Williamsburg was a more or less straightforward, realistic novel, Blenholt has a softer, more poetic essence that throws space and time slightly off-kilter. And yet, Low Company, the final novel in your Williamsburg Trilogy, seems to sweep the mist away and go right back to the hard, realistic concentration on characters and plot. What would you say were the influences that acted on your writing? What did you read?

If Summer in Williamsburg was a more or less straightforward, realistic novel, Blenholt has a softer, more poetic essence that throws space and time slightly off-kilter. And yet, Low Company, the final novel in your Williamsburg Trilogy, seems to sweep the mist away and go right back to the hard, realistic concentration on characters and plot. What would you say were the influences that acted on your writing? What did you read?

Almost everything. There wasn’t much else in those days—no television, no radio. There was, in the beginning, the crystal sets. Do you know about them—the wire coils shellacked around a ten-inch cardboard cylinder, the cat’s whisker? You got the hookup out of the New York Sun. You made your own crystal set and at night listened to the society bands playing at the Manhattan hotel roof gardens. When I was still in high school, I read probably all of Chekhov’s short stories, those gray, sad sketches. I wrote a whole bunch of them, in imitation. At New York City College, I came across the Menorah Journal, a handsome magazine printed on good, thick paper, and it was there that I first heard about Isaac Babel and read one or two of his stories, in a wonderful translation, never again approached, by someone whose name I don’t remember. Babel bowled me over. Before I knew it, I had written a story very much like his Odessa tales. It was published, one of my first, in Story. I imitated Joyce—the story “Little Cloud” in Dubliners. Mine was called “A Clean, Quiet House.” You copy, whether you know it or not. When I wrote for Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post, I generally followed Hemingway. That’s permissible. The only outright plagiarism I’m aware of ever having committed was of a line in a short story by Ralph Manheim. I couldn’t resist it. I stole the line, turned it upside down, and made it mine. It was a wonderful story. I read it sixty years ago, in transition, and still remember it.

But what really worked on me was vaudeville. Back in the old Williamsburg days, there was a theater, The Republic, just a few blocks from my home, on Grand Street Extension. It played five vaudeville acts and the feature picture. I got over there every chance I had. It was all new to me, and enchanted me—a lasting effect. The stories of mine that appeared in The New Yorker are vaudeville—virtuoso mimicries and performed entertainments.

Your stories have a lyric quality that, as I said, made me think of Chekhov, had he been a resident of Brooklyn or Hollywood. John Updike, in a review, says he thinks of you as “a natural … a poet who never has to strain for a poetic effect.” And at the same time, there is Fuchs the hard-minded realist, the breadwinner—thirty years in the studios. That’s a peculiar combination.

You are what you’re required to be. You’re different people, depending on the people you’re confronted with. When I first came to Hollywood, for one reason or another, they thought I was the bookish type, inexperienced in the ways of the world, and that’s the part I played for them—the wide-eyed newcomer. I kept it up, off and on, and for a long time after I was here.

How was it when you first came out to Hollywood?

They heard I had been a schoolteacher—that must have made an impression on them. We were young then, my wife looking even younger, which indeed she was. Mark Hellinger turned me over to Mushy Callahan, to smarten me up and show me the world. Hellinger was a whimsical man. He pulled all kinds of stunts. Mushy Callahan was an ex-welterweight champ. I think I have the division right. He was technical advisor on the fight pictures and ran the studio gym room. Mushy turned out to be a whole lot more inexperienced than I ever was. He was a saint, spic-and-span and shining, always with a happy smile on his scrubbed face. He took me down to the Hollywood fight-club back rooms, where the fighters dressed and got ready, and to the other dungeons, but in the main we racketed around and had a great, merry time together. His real name was Morris Abramowitz, something like that, although I think that was it exactly. He got hit in the face by a horse when he was a newsboy on the Los Angeles streets. His nose was flattened. He looked like a prizefighter, everyone thought he was a prizefighter, so eventually he had to go in for it, and became very good at it, the champ. I genuinely liked these men and admired them as doers, and, now that I’m talking about it, I see the answer—the warm feeling I had for them shook them up and touched them, and they went easy on me.

My father’s favorite Goldwyn line, delivered with a heavy old-country accent—“The great sculptor Epstein has made a bust of my wife’s hand.”

Goldwyn had his own sense of humor. They say, of course, that he knew what he was doing when he came out with those Goldwynisms, that they weren’t all accidental. He was, I thought, a handsome man, fairly tall, beautifully dressed—such suits, shoes and ties. He had, at times, a pixie charm. “You know what day it is today?” he said to us at lunch—we used to sit with him in his studio’s dining room while he held forth. None of us knew. “It’s George Bernard Shaw’s birthday,” he said. He wanted us, after lunch, to go back to our rooms, to stop work in homage and take the day off, to read Shaw, each of us a different play. Goldwyn discoursed on Shaw that afternoon—his fame, his plays, in every country in the world a hit. Goldwyn had gone over to England and sought out the playwright at his home in the country, trying—with no success at all—to talk him into letting him have the rights to Pygmalion. This was long before My Fair Lady.

“Never trust a vegetarian,” Goldwyn said. “Not one of them is honest. In the middle of the night, when nobody is looking and everybody is asleep, they go down to the kitchen and take a piece of chicken out of the refrigerator and eat. They do this all the time.”

How long were you at Warners?

About three years before the war, World War II, and another year or so after, maybe more.

Would you say something about what it was like during those years and who were some of the people at Warners with you when you were there?

Each studio seemed to pick up a coloration, or style, of its own, and was known for it. Warners was supposed to be hard-driving, speedy. They played softball at Paramount and had refrigerators in the writers’ buildings. Metro was the top, the Bank of England—the posh English writers, Joe Pasternak’s talented Hungarians, the Broadway playwrights in New York City. I don’t remember what Twentieth Century Fox or Columbia’s designations were, but they each had one. Fox played softball versus Paramount. Columbia, on Gower Street, was identified with Gulch, the Gower Gulch—cowboys and extras waiting on the sidewalk outside the studio. We had a pretty good collection at Warners—Raoul Walsh, Hellinger, W. R. Burnett, Huston, Irwin Shaw, Faulkner, Frederick Faust, Al Bezzerides, the marvelous Epstein brothers. The Epsteins were the leaders, the main troublemakers. They worked up complicated jokes and excitements. In one stretch they had four smashes in a row, Casablanca, Yankee Doodle Dandy—my favorite—The Strawberry Blonde, and Four Daughters. They couldn’t seem to miss. Nobody believed they could miss. At one time they were trying to get out of their contract with Jack Warner. They read a heap of stuff out of the morning paper to their secretary. She turned it in, and the word came back from the front office—the boys have done it again!

What about William Faulkner? Did you get to know him?

I worked with him. Jerry Wald put me in with him. How this came about—Wald was the locomotive on the lot. He made a good number of pictures we know turned out. He was afraid Faulkner would be too literary or artistic for the job, so he teamed me up with him to show him the ropes and educate him. So, in effect, I was doing for Faulkner what Mushy was supposed to do for me.

What was it like to work with him?

What was it like to work with him?

Intimidating. I couldn’t get close. It was my fault. He would walk down the studio path, erect, wearing a tight, blue, double-breasted blazer with brass buttons, always, alas, the same blue jacket, looking straight ahead of him, not a flicker on his face. There was a silent, secret tumult going on in that man. I’m positive I was right about that. Al Bezzerides took him over. Al took care of him, drove him around—Faulkner had no car—and helped to get him settled in the horrible motel room he lived in while he worked at Warners. The motel was on the Cahuenga Pass, right alongside the steaming traffic. Al urged me to cotton to Faulkner and be friends with him. Al was big and hearty and loving—as he still is—and could get along with anybody. I was from Brooklyn and Faulkner from Oxford, Mississippi, and I was devastated by the paralyzing awe I had for his novels and short stories. I didn’t know how to talk to him. One Saturday after work—people used to work half days on Saturdays—I drove Faulkner to the factory district in downtown Los Angeles. He was having something made up to order, a suitcase—it was for a present for somebody—but he couldn’t get it done the way he wanted. I think the trouble was with the monogram. The initials weren’t satisfactory. Faulkner and the workmen couldn’t understand each other. The workmen finally got it through that they didn’t do the monogram in that section, that we had to go over to another part of the factory, to have the initials removed and the proper ones applied. We were high up in the lofts of the buildings and it was a maze. The workrooms in this factory cut through the walls to the adjoining buildings and we wandered from point to point in that great space. We couldn’t find the monogram department and none of the workmen would tell us. They didn’t know what we wanted. It became nightmarish. It finally got to me and, I’m ashamed to say, I bolted and left Faulkner high and dry—one of those things you later force yourself not to think about.

The assignment for Faulkner and me was to do some rewriting on a picture that was already shooting. Raoul Walsh was the director. The time was short and Walsh did most of the rewriting himself before Faulkner and I could really get it. The picture was based on one of Eric Ambler’s spy thrillers, Background to Danger.

Can you say something about the making of a movie as you experienced it firsthand?

What impressed me about the people on the set was the intensity with which they worked. In the late afternoons, which was when I would go down there, it seemed a mood came over them—a group of people huddled in the barn of the sound stage, lost in what they were doing, oblivious to the world. On one of the early sessions, I watched Joan Leslie and had to smile, entranced by the way she gathered herself together, the way she drove herself in the impersonation of the part—this when she was hardly out of her teens or perhaps still in them. They were artists or talented people—the photographers, set designers, editors, and others whose names you see on the credit lists. They worked with the assiduity and worry of artists, putting in the effort to secure the effect needed by the story, to go further than that and enhance the story, and not mar it.

In the early session I referred to, the scene—played by Leslie and Ida Lupino—takes place in the grimy kitchen of their home in the steel-making city the two sisters live in and want with all their hearts to escape. The griminess of the setting was essential, it was what the script called for, but I felt it would repel the audience just as it depressed me, and I said something of this to our cameraman, who was James Wong Howe. “I’ll do something. You’ll see,” he said. What he did, I saw later, was to produce a softness. The kitchen was still there, but hidden and not there. The black-and-white glossiness centered instead on Lupino and Leslie, casting a vagary over their faces and bodies, making them beautiful and their desire poignant—which is as good an example as I can find to show what I mean, and which may relate to why movie-makers object to colorization. James Agee, in his review of the picture for The Nation, gave special attention to the photography and praised it.

Can you compare the movie-making process with the process you know as a novelist?

The moviemaker has to hold the whole line of the story in his mind—just as the good novelist holds the whole novel in his head—but the chore with the movie is much more onerous since we shoot in fragments, out of continuity, and the balance and values go flying and can get lost. The Hard Way was particularly troublesome because the story is average, with no strong central line to follow—Lupino strives and struggles for Leslie, wrecks Leslie, wrecks Leslie’s husband, Jack Carson, and, in the end, herself and her hopes. The story is aimless, witless, an accident in the making, and would take us nowhere—except for the providential presence of Dennis Morgan in the cast. This is an enigma to me, a story-telling mystery. Morgan has nothing to do whatsoever with the plot. He is in no way involved in the triangle. He is ever the bystander, sometimes uttering a rueful word of warning to his vaudeville-partner Carson, most often just looking on with understanding and forgiveness as the human drama unfolds itself. And yet, he controls the picture. What is it? Morgan makes you believe that he is part of the milieu, but you know he doesn’t belong there, that some warp of fortune has put him in with these people and that he is superior to them. And it is, I think, the innate grace and courtesy in this cool, elegant actor—the thing that was born in him—that gives the picture its point, its meaning and sorrow.

Your Hollywood novel, West of the Rockies, may be the most intimate account ever written of the inner Hollywood. The gritty realism of the book is all the more remarkable for being focused at the very center of the dream-making machinery. Would you comment on how it was you took up novel writing again after so long a hiatus?

Your Hollywood novel, West of the Rockies, may be the most intimate account ever written of the inner Hollywood. The gritty realism of the book is all the more remarkable for being focused at the very center of the dream-making machinery. Would you comment on how it was you took up novel writing again after so long a hiatus?

I turned to the novel again because I thought it was a great story. I had had it with me for many years and finally decided to write it.

Were there particular stars behind the figure of Adele Hogue?

Yes and no. I never knew many movie actresses but I knew people who did and I’ve heard the stories. These actresses are vigorous people. There is so much, so much to be had, and when it slips away from them, the breakdowns can be absorbing. The truth is Hogue is based on a man I knew, a screenwriter, now thirty years dead. He was a paraplegic—polio. His boat, which he kept at Newport Beach and ran down to Ensenada and LaPaz, was his legs. His apartment, or hideaway, was fitted out as a ship’s cabin. When the movie-writing jobs failed him and he lost his yacht, the apartment, the Lincoln Continentals, he would not stand for it and took his life. There was no contest in my screenwriter friend, so I turned him into Adele Hogue, and worked up a licorice-bitter story of Claris, the man who sought to use her or was compelled by Hogue to use her.

Having recently read both The Apathetic Bookie Joint, your collected stories, and West of the Rockies, I see a heightened sense of dramatic economy in your later writing. Were you able to use your screenwriting experience to advantage in your later prose? Would you comment on the difference in writing for the two mediums?

I don’t know about these literary theories and am no good talking about them. Do they do any good? Does anybody benefit from them? Half the time I think we don’t really know what we’re talking about. There is the line, the storyline, the line of action, the run, the continuity, the plot, the mystery of form, the razzle-dazzle from beginning to end—it’s the same in movies or the novel. I wrote in an account some years ago that I thought a good story was so hard to come by that you didn’t really write it, that it existed—that it was out there, and you found it. I once said to a famous editor—he has more books dedicated to him than any man I know, living or dead—that I thought a good story was a matter of luck. He dusted me off, said I was speaking nonsense. Of course, he was right. But maybe there is room for my idea too. When Irwin Shaw came out with that sun-splashed piece of wizardry, “The Girls in Their Summer Dresses,” and I asked him about it, he was honestly taken aback. He was honestly puzzled. His words, as I can recall them, were, “I don’t know. I write the story. If it’s no good, then I write another.” Joseph Mankiewicz, whose work I respect, said in an interview that the most electrifying thing happens in the movie house when you give them the truth. I know what he meant. I have been there. Of course, he didn’t mean the word “truth” literally. He meant the indivisible, the stab, the catch at the heart, the indefinable. You know when you have it. It has sometimes happened to me, and at night when I can’t sleep, I will recite the story to myself, passage after passage, word after word.

Are you currently writing?

Better than ever. I’ve got hold of it. I smile and you think I’m kidding, but I’m completely serious.

Aram Saroyan is a poet, novelist, biographer, memoirist, and playwright; he is the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts poetry awards, one of them for his controversial one-word poem “lighght.”

Tragic Beauty

Axes from The Shining at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Eric Chan, via Flickr

The thing under my bed waiting to grab my ankle isn’t real. I know that, and I also know that if I’m careful to keep my foot under the covers, it will never be able to grab my ankle. ―Stephen King

The rain is pouring up here in Maine: King country. The weather is regenerative and generous, but awfully forbidding, too. Someone hearty told me that this weather is, in fact, the best time to take walks up here—certain vivid mosses have been known to appear. But this is the sort of individual who enjoys icy five A.M. swims, and I did not want to admit that my study of bryology never really extended beyond carpeting bowers for the occasional fairy, and that said experiments generally resulted in pulling up large hunks of moss, moving them, and then being surprised when they died. In short, I am still indoors. And for good measure, we watched The Shining. I remembered it having been much scarier.

Wikipedia:

Cabin fever is an idiomatic term, first recorded in 1918, for a claustrophobic reaction that takes place when a person or group is isolated and/or shut in a small space, with nothing to do for an extended period. Cabin fever describes the extreme irritability and restlessness a person may feel in these situations.

A person may experience cabin fever in a situation such as being in a simple country vacation cottage. When experiencing cabin fever, a person may tend to sleep, have distrust of anyone they are with, and an urge to go outside even in the rain, snow, dark or hail. The phrase is also used humorously to indicate simple boredom from being home alone.

I would expand on this definition, though I’m still in the early stages of cabin fever. I’d say that it can also lead afflicted individuals—individuals, that is, who have finished all the books they’ve brought—to read numerous late-seventies novels featuring insouciant, sexually liberated heroines, who engage in casual screwing (this is the preferred terminology) and say “Christ” a lot. Cabin fever sometimes manifests in numerous terrible attempts at colored-pencil portraiture that make your companions look sort of like Harry Truman. In some cases, there have been instances recorded of butterscotch brownies made without a recipe and bras hand washed in shampoo, because.

Cabin fever, as we know, is a leading catalyst to murder. We live in the post–Scary Movie world; we are jaded to the mechanisms of easy fear. Nevertheless, a small, innocent part of me is willfully alive to the possibilities of horror movie outcomes; although not particularly inclined to it myself, I feel pleasantly murderable. Indeed, if one might be said to encourage such things (not in a London Fields sort of way, I mean), I’d say everything is set in motion: a remote cabin, plenty of woods, and the general arrogant high spirits of an outsider who’s kind of asking for it. I’m not eager for it, but it seems to me better to be mentally prepared. And besides, I would quite like the New York Post to call me a “tragic beauty,” or maybe even a “brainy beauty” because I wear glasses—the beauty bar for the tragic is generously low.

We have joked about it. There were some men working with chainsaws nearby the other day, before the fine weather broke. We could hear the whir of the chainsaws coming closer and closer as we huddled inside. And of course, it wasn’t even scary; it was too much of a cliché. And the men were very nice. I don’t think they saw that I was, secretly, a tragic beauty, just waiting to be recognized.

Read Everywhere, Part 4

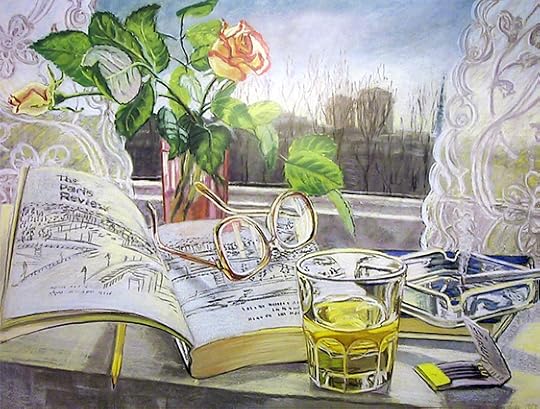

Janet Fish, Untitled, from The Paris Review’s print series.

Celebrate summer—and get summer reading, all year round—with a joint subscription to The Paris Review and The London Review of Books.

The Paris Review brings you the best new fiction, poetry, and interviews; The London Review of Books publishes the best cultural essays and long-form journalism. Now, for a limited time, you can get them both for one low price, anywhere in the world.

Tell us where you’re reading either magazine—or both! Share photos from around the world with the hashtag #ReadEverywhere.

The Serviceable Prose of Jules Verne, and Other News

An 1884 caricature of Jules Verne from L'Algerie, a magazine.

On reading Middlemarch and being twenty-one: “Eliot’s ability to describe people was, in its subtlety and depth and scrupulousness, so many levels above my pay-grade. My own attempts were feeble in comparison. ‘He plays bass and dislikes capitalism and has long hair and an intense look,’ I’d say to a friend in explaining why I liked a certain guy, and the truth was that it was the best I could do.”

Jules Verne was unquestionably imaginative: a science-fiction pioneer. And yet … “Verne may be a master of sorts, but he is not a master of high art. A casual reader, even in English translation, can see that Verne’s prose is rarely more than serviceable and that it gets overheated when he presumes to court eloquence … Each of Verne’s heroes is a nonpareil, the most remarkable man in the world—as long as the reader is immersed in his particular story. Only in other Verne novels—and in television commercials for a Mexican beer—can one find his equals.”

Dungeons & Dragons has turned forty, and, “for certain writers, especially those raised in the seventies and eighties, all that time spent in basements has paid off. D&D helped jump-start their creative lives.”

Archie will die by taking a bullet for his gay friend. “Archie taking the bullet really is a metaphor for acceptance,” Archie Comics publisher and co-CEO Jon Goldwater said, in case you didn’t get it.

From Bach to Deadmau5: a prehistory of electronic-music festivals traces their roots to the nineteenth century.

July 15, 2014

The End

Bastian Schweinsteiger celebrates. Photo: Agência Brasil, via Wikimedia Commons

The World Cup doesn’t end so much as it slips back into itself.

As soon as the whistle is blown one last time, the recaps, the nostalgia, and the smart surmises begin. But then, a day later, after the last team has returned to its home country and the cheers of hundreds of thousands of euphoric fans, the specifics start to stretch beyond the immediate recall they enjoyed during these June and July days. The locations and stadia whose names were on the tip of your tongue begin to hang back as you go forth with your life. You’ve suddenly forgotten the name of that player you didn’t know on that team you weren’t familiar with—the player you’d enjoyed so much that you’d learned to pronounce his name perfectly. Or, if you’re American and have grown through this tournament to love the game, the world may suddenly seem farther away again. The excuses to strike up a conversation with a stranger dwindle. The news of the rest of the world starts with the Middle East again. And left to fend for themselves, the details of your World Cup experience begin to connect their own dots.

Mario Götze—the brilliant, young, attacking midfielder who scored the winning goal for Germany with seven minutes remaining in extra time in the final in Rio de Janeiro, after Argentina enjoyed the clearest chances in the game—becomes Andrés Iniesta, the brilliant, young, attacking midfielder who scored the winning goal for Spain with four minutes remaining in extra time in the final in Johannesburg, after the Netherlands enjoyed the clearest chances in the game.

Unreserved praise for German planning and perseverance as the model for world football becomes unreserved praise for Spanish art and expression as the model for world football.

The thirteenth-ranked 2014 USA team, which showed significant improvement by qualifying after winning one game, drawing one game, and losing twice in Brazil, becomes the fourteenth-ranked 2010 USA team, which showed significant improvement by qualifying for the second round after winning one game, drawing two games, and losing one.

The reigning World Champion, Spain, bowing out meekly in the first round of this 2014 tournament, becomes the reigning World Champion, Italy, bowing out meekly in the first round of the 2010 tournament.

A screwed Brazilian citizenry becomes a screwed South African citizenry.

Two days after the final whistle, after the adrenaline and the big statements, the similarities between the last two World Cups begin to float up from the spectacle-submerged world. It’s been suggested that the scoring and general quality of play in Brazil 2014 put what happened in South Africa 2010 to shame; a record 171 goals were scored in this World Cup, as opposed to 145 in South Africa.

And yet, once the elimination games began, an ever-increasing familiarity descended. The matches become tight, cautious, low scoring, at times cynical, occasionally violent. Four of the knockout games succumbed to the succor of a penalty-kick shootout; another four, including the final itself, dragged into extra time, the tired legs of increasingly ineffective players dragging behind. Only two teams scored more than two goals after the group stages of the tournament; both of those teams did so against the host, Brazil. And though Brazil’s 1-7 loss to Germany may seem an outlier in terms of the result, the impact felt eerily familiar to the experience the last time Brazil hosted the World Cup—the 2-1 defeat to Uruguay, commonly known as “the Maracanazo.” We weren’t witnessing a once-in-a-lifetime hiding. We were witnessing an updated cover of that hiding.

So why did everything go so quickly from spectacular to so-so? Simply put, it’s a sign of the times. Everything is captured digitally these days. If you advance-scout a blind date, you can rest assured that nations advance-scout their opposition. No player is a surprise to another team, no tactical variation will have been untried by the time of the elimination games. Risk aversion becomes righteousness. The reduction of event supercharges the occurrence of an event. Games become balanced on the distress of an atom.

This doesn’t mean that the backend of the tournament was bereft of excitement. But Germany’s disposition toward offensive football was, in the end, hardly contagious. The consensus seems to be that Argentina had plenty of chances, but they only managed two shots on goal. And Leo Messi found himself playing in an Argentina side that chose similar tactics to those he plays against with FC Barcelona: keep things compact, go for broke on the counter. Divorced from the ball, hoping for a glimpse of it as he defended some game-planned space on the field, he must have felt like he was playing in an alternate universe. In 2018 he’ll be thirty-one. A better ending then, maybe in a Moscow final, isn’t beyond his abilities. But the difference between Argentina winning and losing this year’s World Cup was never about Messi’s abilities.

It’s fitting that the team that played most like a team, and practiced the most open-attacking game, won the whole thing. Germany scored the most goals in the tournament and did so with the proposition of attacking football. That said, their biggest accomplishment was getting their house in order. Their first game, a 4-0 pasting of Portugal, had them playing with no striker, their fullback as a defensive midfielder, four central defenders, and the aforementioned Götze in the starting lineup. That game was as good as it got for that lineup, and after a few uninspiring performances, instead of staying the course (the equivalent of spitting downwind like Brazil did), the German coach, Joachim Löw, made significant changes. Among those was the relegation of Götze, the wonder boy of German football, to the bench. He reappeared in the starting lineup for the first elimination match against Algeria but was benched at the half, the football equivalent of being given the trap-door treatment. He spent the rest of the tournament as a substitute. After the match, Löw divulged to the press that he told Götze to go out there and show the world that he’s as good as Messi. Götze must not have heard him. He showed the world he was as good as Iniesta, who to this very day still receives a standing ovation from fan and foe alike in every Spanish stadium.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s second book of poems, Heaven, will be published next year. He is the recipient of the 2013 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award.

To Be Enjoyed

Happy birthday to Iris Murdoch, who would be ninety-five today. “A readable novel is a gift to humanity,” she said in her 1990 Art of Fiction interview:

It provides an innocent occupation. Any novel takes people away from their troubles and the television set; it may even stir them to reflect about human life, characters, morals. So I would like people to be able to read the stuff. I’d like it to be understood too; though some of the novels are not all that easy, I’d like them to be understood, and not grossly misunderstood. But literature is to be enjoyed, to be grasped by enjoyment.

That interview with Murdoch was conducted by James Atlas as part of a collaboration between 92Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center and The Paris Review—it was recorded live at 92Y on February 22, 1990, and you can listen to an audio recording of it above.

As Atlas later remembered their encounter,

She was anything but forbidding. She was modest. When I asked her what she thought she had achieved—remember, she was over seventy at this point and had long been considered one of the most important writers in England—she answered, with complete sincerity, “I haven’t achieved anything yet.” She was profound without sounding that way, or, I suspect, even knowing that she was: “Live in the present. It’s what you think you can do next that matters.” And she was funny: “The thing about the theater is, why do people stay there? Why don’t they just get up and go?” But the most valuable thing I learned from Dame Iris Murdoch that evening was about the relationship between art and humility. “One is always discontented with what one has done,” she said. “One always hopes to do better.”

Power Tools

The wonders of industrial-supply catalogs.

Photo: Jjron, via Wikimedia Commons

When I was nine or ten, riding in the backseat of my mom’s car as we drove the gauntlet of strip malls, car dealerships, big-box stores, and fast-food franchises that constituted our suburb’s commercial district, I realized that all of the tall signs and buildings had been constructed and erected by actual people, different crews of people. I thought about all the Burger King and Mattress Discounters signs in the world, how each had been shipped from somewhere, delivered to someone, received, assembled, mounted, electrified. I attributed a lot of power and reach to corporations, especially those that advertised on TV, and to understand that they comprised real people was something of an epiphany—especially in suburbia, where corporate authority rests in the illusion that no human labor has gone into transforming and homogenizing the landscape. All the stores were just there. What else could there be?

That moment is part of what informs my fascination with the Grainger catalog, a massive, 4,322-plus page industrial-supply inventory with which I first became acquainted last year, when a friend gave it to me for my birthday. Released annually on February 1, it’s an omnibus of 590,000 products—power tools, fasteners, pneumatics, hydraulics, pumps, raw materials, janitorial necessities, HVAC and refrigeration components—a work of pure utility, designed, honed, and focus-grouped to provide ready access to its most arcane sections. I can’t get enough of it. For the uninitiated, it provides a glimpse at the invisible infrastructure girding the world of construction, maintenance, repair, and operations. Grainger’s aggressively salt-of-the-earth slogan is “For the Ones Who Get It Done,” and the joy of perusing its catalog is in seeing how very many things there are to get done, and how many ways we have of doing them.

And so I often reach for it in pursuit of a kind of materialist awe. It makes for a reading experience more engaging, imaginative, and informative than almost anything that passes as literature. I’ve put down novels to pick up the Grainger catalog, which holds court on my coffee table and which could, in a pinch, serve as a coffee table unto itself.

Grainger sells mail-room organizers, carpet deodorizers, hairnet dispensers, and gutter-deicing cables. They sell a three-stage, heavy-traffic floor-matting system designed to entrap heavy debris. They sell miniature high-precision stainless-steel ball bearings with extended inner rings. They sell 550-foot rolls of foam for protecting electronics and an oil-filtration system for high-viscosity fluids. Their catalog contains a proliferation of heavily modified nouns that denote things I never knew existed, or things I’d intuited to exist, but had never really considered.

Metalized polyester film tape.

GMP/GLP data output moisture analyzers.

Electrostatic dissipative (ESD) gloves.

Cup point alloy steel socket set screws.

Catalog #405

In the specificity of its language, the catalog summons a rigorously taxonomic legion of hardware and stuff, the matter from which cities and roads are composed, the contrivances that keep machines running and power flowing and ventilators ventilating. It puts a real gleam on human ingenuity. We made these things. They’re everywhere. Spend enough time poring over the catalog and it begins to color your world; you’ll close it and walk to the refrigerator only to find yourself marveling at the hinges, screws, grilles, handles, nozzles, toggles, crisper drawers, and various constituents of the appliance instead of getting a beer. Who needs a beer? You could own a wide selection of pneumatic solenoid air valves.

Or push/pull paddle tubular locksets.

NIOSH-approved ISCBA industrial SCBAs.

Wall-switch occupancy sensors.

NSF-listed plate casters.

Then there are the item descriptions. If “For sale: baby shoes, never worn” counts as a story, then so, too, must “all-wood coffins store flat and assemble without tools. Can be stacked 3-high when assembled to maximize space in mass-casualty emergencies.” Or: “High-visibility warning whips alert other vehicles of your presence.” Or: “Stretch knit material covers head to protect from overspray.”

Arguably literature’s basic charge is to describe being in the world—the Grainger catalog reveals just how extensively our writers have failed to document the varieties of work happening now, and the hyper-precise terminology surrounding that work. Poetry and prose are some of the few venues for a culture to examine its language; in a sense, the bulk of our poetry and prose is marked by a paucity of information.

Granted, a novel full of phrases like “light- to medium-traffic dry-area antifatigue matting” wouldn’t make for a terribly lively read—if someone were to publish a hyperrealist story in which a plumber solves a complicated problem with a schedule-eighty polypropylene socket-fused fitting, I alone might find merit in it. But look at writers like Wallace, whose fascination with neologisms captures the sea change that technology has brought to bear on how we communicate; or Leyner, with his satirical slumgullion of pharmaceutical jargon and high-impact ad copy; or DeLillo, whose “Human Moments in World War III” declares, “The thing science does best is name the features of the world.” There’s room for potent work that wrestles with the flux and expansion of our syntax.

I want the Great American Static-Resistant Sorbent Novel.

Two-in-one squeegee pushbrooms.

Negative-rake carbine turning inserts.

Flange-mount disconnect enclosures.

* * *

A sample page from the latest Grainger catalog.

Grainger was founded in 1927 by William Wallace Grainger, a Chicago electrical engineer who sold hard-to-find motors out of the back of his station wagon. His first catalog was eight pages. He called it the MotorBook.

Deb Oler—vice president and general manager, Grainger Brand—was kind enough to indulge my obsession with the catalog, which she proclaimed “the largest printed book in the world.”

“We can’t actually make it any bigger,” Oler told me. “We spent a huge amount of time working with the people who make our paper to make it as thin as it can possibly be while still holding up for a really long period of time. We always think, What are things we can do to get more space? But we can’t bind any bigger than we bind now.”

Its distribution is two and a half million. Only two printers in the world have the technology to produce it. The ultra-lightweight paper—that’s the technical term—is so tissue thin that a Bible’s looks lavish in comparison, but preliminary evidence suggests the catalog is dense enough to stop a bullet. The entire project comes down to a “team of thirty, a very tenured group of people,” and of these, only eight are dedicated to copyediting—no mean feat, given that in my many hours with the catalog I’ve discovered only one typo.

Compiling a book of this size poses obvious editorial challenges. For one: What goes in, what stays out? Oler said, “We have hard hats that have every football team in America’s logo on them. Do we need to show all of those, or can we show a representative sample? Will people’s feelings be hurt because their team isn’t there?”

And what do you call things, how do you file them? Drinking fountains, for instance, which Grainger sells, are known in various parts of the nation as water fountains, bubblers, or coolers. There are trash cans and then there are waste receptacles and garbage bins. All of this occasions impassioned semantic debate. The deep, quasi-Teutonic satisfaction of the Grainger catalog is that everything, finally, has been named. Everything has been indexed and put where it belongs.

Diamond-knurled press inserts.

Self-sealing pan-head machine screws.

Octal-base specialty voltage relays.

“We spend time watching people use the catalog in native situations,” Oler said. “We time how long it takes to find things. We time what happens when we take things out or put new things in.”

There are those who would object to the waste of a printed volume like this. No matter how responsibly its paper is sourced—Oler made mention of the Forest Stewardship Council—it’s still a cumbersome, tree-hungry tome. But there are few books whose design and function make such a convincing argument for their existence in print. The Grainger catalog has colored indices at its center, where the book stays open and its pages can be flipped more easily with one hand. It has a durable spine and a series of black bands running down its edge to designate different sections.

“When the customer shows up, they have a problem,” Oler said. “Either something isn’t working or isn’t going to work.” The catalog is one of the few reference texts around whose print iteration is more efficient than its digital counterpart. You look in it to find things and you find them. It is, itself, a tool, designed to provide “the right amount of information to make a decision quickly.”

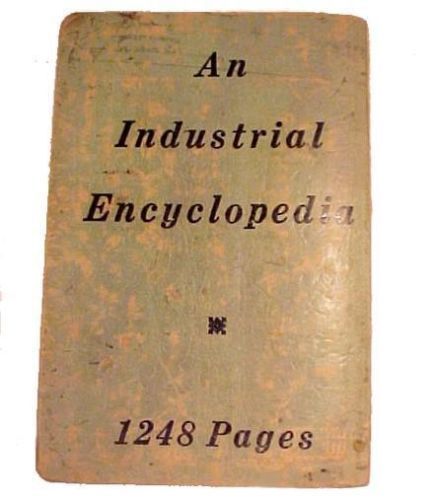

The back of a 1935 McMaster-Carr catalog.

Of course, though it’s nearest to my heart, the Grainger catalog is not the only one of its kind. There’s also the McMaster-Carr, whose distinctive yellow cover and limited print runs make it especially coveted by industrial-supply fetishists: the backsides of early twentieth-century editions bore the label “An Industrial Encyclopedia.” There’s Fastenal, which calls its catalog “Big Blue,” and MSC Industrial Direct, which puts out “The Big Book”—names that suggest the engulfing totality of this enterprise. Above all, an industrial supplier strives to be comprehensive. What’s seductive about these catalogs is the promise of a certain exhaustive quality, a list so meticulous as to seem interminable. “Our customers have told us time and again,” Deb Oler said, “I want to be able to come to you for everything.”

Such as solar-powered automatic gable-mount attic ventilators.

Ultrasonic wall-thickness gages.

Expandable gravity skate-wheel conveyors.

“Our customers are the people that sit in the background of every business,” Oler told me. “You don’t think about your light bulbs until they’re off. You don’t care about the toilet or the sink until it doesn’t work. The people who are our customers … they’re MacGyvers. They see themselves as problem solvers, and they are. If you look at any building and the people who work in it, there are literally thousands of products that you would need to keep that building operating.”

Even so, their best-selling product, Oler said, is probably toilet paper.

Blue True Dream of Sky

The schooner Isaac Evans, under full sail on Penobscot Bay in Maine. Photo: Joe Berkall

“You’ve certainly had good weather,” people keep telling us. They say this almost resentfully, as if we do not appreciate the honor being conferred, could never understand the rarity of a full eight days of cloudless blue skies and temperatures in the midseventies, in coastal Maine, in early July.

The weather forecasts have been equally dour. Don’t get your hopes up, they seem to say. Each morning, the icon on my phone will show a sun cautiously peeping out from behind a cloud. If the forecast must admit to the possibility of sunshine, it does so reluctantly: Yes, it is fair now (say the icons) but at three P.M., there will be a cloud. Not three? Four. Five, then. Certainly by six. Well, anyway, sunset is at seven, so then your fun’s over. Never once has that cloud departed from the screen, even as the skies have stayed stubbornly blue.

I don’t care; nothing can dim my excitement. I have not gone on “vacation” in many years. I am not sure how to do it, although I have notions. I read E. B. White and The Lobster Gangs of Maine in preparation. Streamed Stephen King adaptations. Isn’t that what you do? Thus warned, I came braced for a range of weathers. I packed slickers and boots and ghost stories. (Puzzles, I was told, the house already had.) I privately harbored gingerbread-related plans.

Instead, the aggressive, unflagging beauty began to feel vaguely tyrannical: it seemed an act of gods-tempting hubris to miss a single moment of potential hiking or swimming or general beauty-celebrating. We did not take our luck for granted; to the contrary, each day, when I set out for a walk or a ride on the bicycle I was borrowing, I tried to give a little ecumenical prayer of thanks.

i thank You God for most this amazing

day: for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky; and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes

(Maybe not ecumenical, exactly, since Cummings was Unitarian.) Once, some people carrying racquets heard me, which was embarrassing. I’m sure they could tell, too, that I can’t play a decent game of tennis.

Then finally, today, the “good” weather broke. It was something of a relief. They don’t call it high-pressure for nothing. The fog did not burn off this morning, but instead settled low over the mountains; the rain patters down and occasionally lightens to a mist.

But I regret to inform you that, for those of us just passing through, it is still beautiful and novel and rare. Or maybe people really do just like to talk about the weather?

Cover Your Eyes—Pubes! and Other News

Leena McCall’s Portrait of Ms Ruby May was recently removed from a gallery for its supposedly offensive depiction of pubic hair. Image via Slate

Ninety-eight years ago this month, Edith Wharton published Summer, a steamy novella “with a plotline that includes sex outside of wedlock, an unplanned pregnancy, and a truly disturbing relationship between a teenage girl and her guardian.” It was not well reviewed.

Nor, apparently, was When Harry Met Sally, which, though it eventually ascended into the rom-com pantheon, was widely dismissed when it came out twenty-five years ago. Terrence Rafferty wrote, “The debate, of course, is too shallow to engage us, but they might have tried providing a little plot … When Harry Met Sally positions itself comfortably in the middle of nowhere and casts knowing directions in all directions.”

On Virginia Woolf’s conception of privacy: “Many people accept the idea that each of us has a certain resolute innerness … What interested Woolf was the way that we become aware of that innerness. We come to know it best, she thought, when we’re forced, at moments of exposure, to shield it against the outside world.”

Today in prudery: in London, the Society of Women Artists’ annual exhibition featured a portrait by Leena McCall, which depicted—trigger warning!—a bit of pubic hair. But don’t worry! Calm down! The painting was summarily removed because it was “pornographic” and “disgusting.”

In the nineties, Prodigy was one of the most successful internet companies around—an “interactive personal service” that finally went belly-up in 1999, taking with it “the written record of a massive, unique online culture, including millions of messages and tens of thousands of hand-drawn pieces of digital art.” Now one man has recovered some of that early Web culture.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers