The Paris Review's Blog, page 685

July 10, 2014

Real Talk

INTERVIEWER

Was the community you grew up in pleased about your career?

MUNRO

It was known there had been stories published here and there, but my writing wasn’t fancy. It didn’t go over well in my hometown. The sex, the bad language, the incomprehensibility … The local newspaper printed an editorial about me: A soured introspective view of life … And, A warped personality projected on …

—The Art of Fiction No. 137, 1994

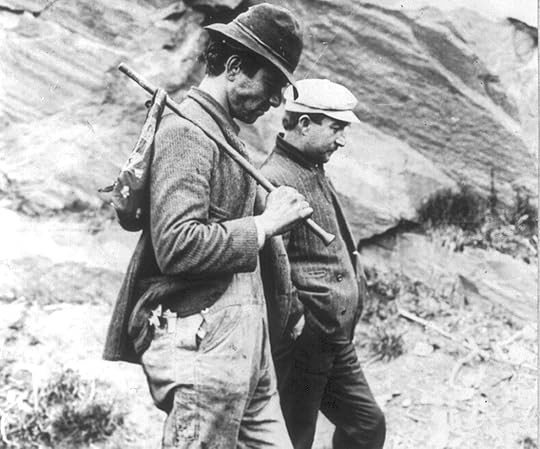

Happy birthday to Alice Munro. In this 1979 clip from Take 30, a Canadian talk show, Munro—who’s eighty-two today—discusses the less-than-warm reception her collection Lives of Girls and Women received in her native Huron County, where a conservative group argued that it should be expunged from twelfth-grade syllabi. She speaks here to Harry Brown (whose three-piece suit yours truly wouldn’t mind owning) about fighting the proposed ban.

This is the kind of talk show that’s all but extinct today, in which two unadorned, ordinary-looking people have an intelligent conversation without a studio audience, or a ticker scrolling beneath them, or a host of other distracting stimuli that have come to seem normal. But what’s more eye-opening is how little has changed since then. The controversies stalking literature in 1979 are almost identical to today’s bugbears: declining readership, increasing moral turpitude. A debate, in other words, about what literature should do and who it’s for.

“Many people don’t read much and don’t think books are very important anyway,” Munro tells the interviewer. And:

As far as I can tell from the talk of the people who are against the books, they somehow think that if we don’t write about sex, it will disappear, it will go away. They talk about preserving their seventeen-year-old and eighteen-year-old children, protecting them. Well, biology doesn’t protect them. They don’t need to read books.

It’s not clear whether Munro succeeded in stopping or overturning the ban, but apparently the events in Huron County “inspired the Book and Periodical Council of Canada to launch Freedom to Read Week, an annual celebration of freedom of expression.”

Read Everywhere, Part 3

“Megan getting her head around the LRB at the British Museum.”

Celebrate summer—and get summer reading, all year round—with a joint subscription to The Paris Review and The London Review of Books.

The Paris Review brings you the best new fiction, poetry, and interviews; The London Review of Books publishes the best cultural essays and long-form journalism. Now, for a limited time, you can get them both for one low price, anywhere in the world.

Tell us where you’re reading either magazine—or both! Share photos from around the world with the hashtag #ReadEverywhere.

In Defense of Fanny Price

Mansfield Park at two hundred.

A publicity still of Billie Piper as Fanny Price in a 2007 adaptation of Mansfield Park.

Poor Fanny Price. The unabashedly mousy, pathologically virtuous protagonist of Mansfield Park—which turns two hundred this year—is Jane Austen’s least popular heroine. She spends most of the novel creeping around the periphery of the titular park, taciturn and swallowing tears; she tires after the briefest of physical exertions; she looks down on her wealthier cousins for engaging in flirtatious amateur theatrics; and for most of the book’s five hundred pages, she refuses to voice her long-held love for her cousin Edmund.

Austen’s own mother reportedly found Fanny “insipid”; the critic Reginald Farrer described her as “repulsive in her cast-iron self-righteousness and steely rigidity of prejudice.” Even C. S. Lewis—in the voice of his demon Screwtape in The Screwtape Letters—let loose a vitriolic rant about Austen’s most priggish heroine, calling her “not only a Christian, but such a Christian—a vile, sneaking, simpering, demure, monosyllabic, mouselike, watery, insignificant, virginal, bread-and-butter miss … A two-faced little cheat (I know the sort) who looks as if she’d faint at the sight of blood, and then dies with a smile … Filthy, insipid little prude!” Even if we are to separate Lewis from Screwtape, it’s difficult to see Fanny as anything but, to quote Nietzsche’s famous description, “a moralistic little female à la [George] Eliot.”

And indeed, those who defend Fanny tend to see her as a Christian heroine in the mold of a Dorothea Brooke. As the Austen biographer Claire Tomalin puts it, “it is in rejecting obedience in favor of the higher dictate of remaining true to her own conscience that Fanny rises to her moment of heroism.” But to read Mansfield Park as a kind of Middlemarch is to miss the far more complicated story Austen has told. Fanny Price’s story is less about her individual virtue, or her richer relatives’ lack thereof, but about class, about privilege in its most insidious form—before the term ever cropped up in contemporary social justice discourse. Fanny isn’t moral or upright because she wants to be, but because the role—along with a whole host of so-called middle-class values—is forced upon her. For all we know, she may well wish to be as carefree, as filled with dynamic sprezzatura, as Woodhouse or Elizabeth Bennet, Austen’s more fortunate heroines, but the social dynamic, and the circumstances of her birth, deny her the security necessary for such frivolity. Fanny has too much at stake to be easygoing.

She is, after all, a poor relation, sent to live with her wealthier cousins at Mansfield Park by a kind of nominal charity. From the first, her rich aunt insists that she never forget her social inferiority to her cousins:

I should wish to see them very good friends, and would, on no account, authorise in my girls the smallest degree of arrogance towards their relation; but still they cannot be equals. Their rank, fortune, rights, and expectations will always be different. It is a point of great delicacy, and you must assist us in our endeavours to choose exactly the right line of conduct.

When Fanny is first understood by her cousins to be dull and stupid—qualities the reader soon comes to find in her, too—it’s not because of anything she has done but simply because of what lacks in her background:

They could not but hold her cheap on finding that she had but two sashes, and had never learned French; and when they perceived her to be little struck with the duet they were so good as to play, they could do no more than make her a generous present of some of their least valued toys, and leave her to herself, while they adjourned to whatever might be the favourite holiday sport of the moment, making artificial flowers or wasting gold paper.

Their aunt’s reply to this disdain is telling: “It is very bad,” she tells her children, “but you must not expect everybody to be as forward and quick at learning as yourself.”

The qualities of your typical Austen heroine—charming, forward, quick at learning—are rooted in privilege; Mrs. Norris is blind to the fact that such qualities, along with the possession of scarves or an in-depth knowledge of French, are learned, not inherent. And so Fanny is never given the chance to exhibit the qualities of a “good” Austen heroine; she’s told from childhood that she is dull, stupid, and inadequate until she herself internalizes “my situation—my foolishness and awkwardness.”

Many critics of Fanny focus on her approach to an amateur production of the flirtatious Lover’s Vows—performed by her cousins, along with two charismatic acquaintances, Henry and Mary Crawford—who embody the charm and worldliness Fanny lacks. She disapproves of the proceedings, which see the arrangement, under the guise of acting, of various romantic alliances and mésalliances. But her disapproval, as too few critics note, comes less from prudery about the theater itself than from an awareness that acting Lovers’ Vows is an a excuse to get away with essentially cuckolding her cousin’s hapless fiancé. While she is tempted by the idea of acting in theory—“For her own gratification she could have wished that something might be acted, for she had never seen even half a play”—in practice, Fanny is well aware that Lovers’ Vows will (and does) offend Sir Thomas, the family’s absent patriarch, upon his return. It’s the latter argument that underpins the objections of Fanny’s cousin Edmund—her sole ally in the house: “I am convinced that my father would totally disapprove it … my father wished us, as schoolboys, to speak well, but he would never wish his grown-up daughters to be acting plays. His sense of decorum is strict.”

Fanny’s fear of giving offense may seem like further evidence of her priggishness. After all, Sir Thomas’s own children have no such fear. Coddled, spoiled, and beloved, they’re perfectly aware that Sir Thomas’s wrath, whatever form it might take, will have few material consequences for them. So, too, Henry and Mary Crawford, who, by their wealth and social status, are largely shielded from consequence. But Fanny has no such protection. She’s reminded at every turn that her presence in the house is contingent upon the good will of her social betters. Should she offend her foster family—as she does, later on in the novel, by refusing to marry the eligible Henry Crawford—she will be considered “a very obstinate, ungrateful girl.” And then it’s back to her comparatively impoverished biological family.

Compare Fanny with Mary Crawford, the novel’s ostensible antagonist. Witty, charming, beautiful, and carelessly rich, Mary has more surface qualities in common with the typical heroines of Austen’s fiction than Fanny does. She schemes like Woodhouse; she’s as witty as, if not wittier than, Elizabeth Bennet; she makes risqué remarks, acts in flirtatious plays, and risks offending Sir Thomas. But she gets away with all this only because her actions have few real consequences. Her blithe worldliness, her willingness to transgress ostensible taboos, comes from the fact that she resides firmly within a fundamentally safe social sphere of immense privilege. It’s Fanny, really, who’s the more authentically transgressive of the two. By reminding her cousins of Sir Thomas’s potential disapproval, as well as of the morally questionable (and quasi-adulterous) flirtations the Bertrams and the Crawfords use Lovers’ Vows to disguise, she calls attention to her middle-class inability to engage in the same carefree pseudo-risks of her aristocratic peers. (Even when Maria Bertram’s adulterous affair with Henry Crawford becomes public, she’s hardly left to fend for herself in the street—her punishment is to spend the rest of her life abroad with her garrulous aunt.)

Arguably, by contrasting Fanny with a “typical” Austen heroine like Mary, Austen challenges us to read with a sharper eye to social class, and how such class informs her work as a whole. It can hardly be an accident that Austen is explicit about Mansfield Park’s wealth’s dependence on the slave trade—a dependence she does not highlight in connection with, for example, Mr. Darcy’s Pemberley. By seeing Mary through Fanny’s eyes, we wonder, too, how Austen’s and Elizabeth might appear to someone like Fanny, and whether they, too, get their literary appeal from qualities inherent to their social position. In wanting Fanny to be cleverer, bolder, sexier than she is—in wanting her to be more like Mary—we become complicit in the world of Mansfield Park, and in the politics of exclusion through which Mansfield thrives.

If we construe Mansfield Park as a morality tale, or as a book about Fanny herself, we fundamentally misread Austen’s novel. It’s not called Fanny Price, after all. Mansfield Park highlights, as no other Austen novel does, the role that class and class privilege play in determining the popular qualities for a heroine’s charm and wit—characteristics that depend on an ability to transgress without consequence. It might be the most quietly subversive of Austen’s novels—weakening the foundations not only of its titular park but of Pemberley as well.

Tara Isabella Burton’s work has appeared in National Geographic Traveler, Al Jazeera America, the BBC, the Atlantic, and more. She is working on a doctorate in theology and literature at Trinity College, Oxford and has recently completed a novel.

Authors Can’t Make Ends Meet, and Other News

Photo: Library of Congress

New statistics—the Guardian calls them not “shocking” but “ ‘shocking’ ”—suggest that “the number of authors able to make a living from their writing has plummeted dramatically over the last eight years, and that the average professional author is now making well below the salary required to achieve the minimum acceptable living standard” …

… So why are authors undervalued? If they’re “reluctant to see what they do as a real job, deserving of a real salary, then who can blame the public for taking advantage of their work? … In the dark old days, the storyteller always had the best place by the campfire. Those days may be gone, but the power of story remains.”

On palimpsests, digital reading, and erasable books: “To make a kind of loose analogy between a palimpsest and modern technology, computers often use a codec, or program that transfers information from one format into another, and a codec often loses content when moving between formats … What information are we devaluing now?”

Talking to Richard Linklater about his new movie, Boyhood, which was filmed over twelve years as its lead grew into an adult: “There would be few big moments. Instead, Linklater sought out the small truths of youth: friends lost forever after a move, adult choices children can’t understand, dull shifts at minimum-wage summer jobs. Passivity—not drama—dominates Mason’s days … Linklater admits he’s ‘at war’ with traditional narrative.”

Who’s the better prognosticator, Isaac Asimov or Tyra Banks?

July 9, 2014

Anne Hollander, 1930–2014

Anne Hollander, whose acute writing on fashion, costume, and style infused those subjects with a new intellectual energy, died on Sunday at eighty-three. As the Times reports, “She argued that clothing revealed far more than it concealed—about art, about perceptions of the body and ourselves—and her interests spanned centuries and mediums.”

Hollander conducted—or co-conducted; she shares the credit with John Marquand—The Paris Review’s first Art of Theater interview, with Lillian Hellman, published in 1965. Back then, her contributor’s note read modestly, “Anne Hollander designs costumes, paints, and translates occasionally.”

A little more than a decade later, in 1978, she published her first book, the brilliant (and brilliantly named) Seeing Through Clothes, a history of clothing and a study of representations of the body in Western art. The book was full of offhand wisdom about what you could call our philosophy of dress: “People seem always actually to know,” Hollander wrote, “with a degree of pain that has required the comfort of fairy tales, that when you are dressed in any particular way at all, you are revealed rather than hidden.” The book took a while to find its audience, but, as one critic noted, it “pushes erudition to the point of originality. The thoroughness with which she examines Western art and clothes has precipitated a new subject: how painting, sculpture and photography mediate between bodily ideals and what we wear.”

Over the next decades, her reputation grew and she published a succession of well-received books, including Moving Pictures and Sex in Suits; she wrote essays for a number of magazines, including The London Review of Books. Not much of Hollander’s writing is available online, but she was, for a time in the late nineties, the fashion columnist for Slate, which has curiously yet to publish a remembrance. Her pieces there have aged well; a column from February 1997—“A Loss for Words: Why there’s no good writing in fashion”—is just as true nearly twenty years later:

Fashion journalists and sensational fictioneers like Danielle Steele have co-opted the field, and other writers are scared off. Fashion now seems like a club with a private jargon that leaves no room for the play of sensitive literary exposition. And good critical writing about clothing hardly exists at all. There is no tradition of clothes criticism that includes serious analysis, or even of costume criticism among theater, ballet, and opera critics, who do have an august writerly heritage. This fact may be what makes the fashion journalist hate her job—the painful sense that real work cannot be done in this genre, that it would be better, more honorable, to be writing about something else.

But Hollander didn’t write about something else, thankfully. She expanded the rhetoric and insight of criticism about style, engaging where most writers thought there was nothing to engage with.

Anne Hollander, 1930-2014

Anne Hollander, whose acute writing on fashion, costume, and style infused those subjects with a new intellectual energy, died on Sunday at eighty-three. As the Times reports: “She argued that clothing revealed far more than it concealed—about art, about perceptions of the body and ourselves—and her interests spanned centuries and mediums.”

Hollander conducted—or co-conducted; she shares the credit with John Marquand—The Paris Review’s first Art of Theater interview, with Lillian Hellman, published in 1965. Back then, her contributors’ note read modestly: “Anne Hollander designs costumes, paints, and translates occasionally.”

A little more than a decade later, in 1978, she published her first book, the brilliant (and brilliantly named) Seeing Through Clothes, a history of clothing and a study of representations of the body in Western Art. The book was full of offhand wisdom about what you could call our philosophy of dress: “People seem always actually to know,” Hollander wrote, “with a degree of pain that has required the comfort of fairy tales, that when you are dressed in any particular way at all, you are revealed rather than hidden.” The book took a while to find its audience, but, as one critic noted, it “pushes erudition to the point of originality. The thoroughness with which she examines Western art and clothes has precipitated a new subject: how painting, sculpture and photography mediate between bodily ideals and what we wear.”

Over the next decades, her reputation grew and she published a succession of well-received books, including Moving Pictures and Sex in Suits; she wrote essays for a number of magazines, including The London Review of Books. Not much of Hollander’s writing is available online, but she was, for a time in the late nineties, the fashion columnist for Slate, which has curiously yet to publish a remembrance. Her pieces there have aged well; a column from February 1997—“A Loss for Words: Why there’s no good writing in fashion”—is just as true nearly twenty years later:

Fashion journalists and sensational fictioneers like Danielle Steele have co-opted the field, and other writers are scared off. Fashion now seems like a club with a private jargon that leaves no room for the play of sensitive literary exposition. And good critical writing about clothing hardly exists at all. There is no tradition of clothes criticism that includes serious analysis, or even of costume criticism among theater, ballet, and opera critics, who do have an august writerly heritage. This fact may be what makes the fashion journalist hate her job—the painful sense that real work cannot be done in this genre, that it would be better, more honorable, to be writing about something else.

But Hollander didn’t write about something else, thankfully. She expanded the rhetoric and insight of criticism about style, engaging where most writers thought there was nothing to engage with.

No More Tears

This “Jesus Wept” photo became a meme in the aftermath of Brazil’s defeat yesterday.

O Lachryma Cristi, what has happened to our weepy Brazilians? Since day one of this tournament, it seems, they have been in tears. As the technical director Carlos Alberto Parreira reported, “They cry during the national anthem, they cry at the end of extra-time, they cry before and after the penalties.” The sports psychologist Regina Brandão was rushed in, but failed to stem the flow; then it was The Pressure! The Pressure! A nation’s hopes, etc., etc.

And now this 7-1 pasting, the iconic gone-viral boy in the crowd, glasses pushed up, fingers pressed to eyes, sobbing into his Coca-Cola cup; and somewhere else not too far off, the pretty girl with tears streaming down her cheeks, rivulets slowly obliterating the Brazilian flags she had painted there. Wherever you look, buckets—David Luiz crying, Oscar, his face pressed down soaking someone’s shoulder. Cry me a river—the river cried turned out to be the Amazon. Meanwhile, the Germans never shed a tear, although Mesut Özil looked as if he might cry when Bastian Schweinsteiger yelled at him for missing an easy opportunity to put goal number eight past Júlio César. Lighten up, Bastian!

And now the hundred-foot-high concrete Christ the Redeemer that stands with arms outstretched, gazing over Rio from the peak of the Corcovado mountain, has been Photoshopped with its hands to its face, a meme for the ages.

The truth is that Brazil had been running on half a tank (or empty) since the World Cup began. They were gifted the opening game against Croatia, worked a scoreless draw with Mexico, and beat a hopeless Cameroon team more worried about its wages than soccer; they could easily have lost to Chile, and they brutalized Colombia into submission. Against Germany, without Neymar and Thiago Silva, Brazil was utterly exposed: a ragged defense, scattered midfield, and strikers as bland and sluggish as the names Fred and Hulk would suggest. Germany, an excellent team even though Müller wears funny socks, may well go on to win the World Cup, but they will not beat either Holland or Argentina 7-1.

Those seven goals brought Brazil’s coach, Luiz Felipe Scolari, the “worst day of [his] life.” I suggest copies of British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips’s recent book Missing Out for him and everyone on his team. Phillips wants us to live the life we have, and not the one that we imagine erroneously we might have had, if we were contenders. That route leads to a bad narrative, “and what was not possible all too easily becomes the story of our lives.” In all the soul-searching, all the talk of distress, disturbance, and suffering in Brazil, the scars that will never heal, the everlasting shame and so on, a useful perspective has been lost: Brazil didn’t lose a war with millions of dead. It lost a soccer game! Put the handkerchiefs away—or, as Phillips says, “Our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless trauma about, the lives we were unable to live.” Even with the home field advantage, Brazil was never truly a contender to win this World Cup, and all the bells say, too late. This is not for tears. Adam Phillips to replace Regina Brandão for World Cup Russia 2018?

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

The Many Poses of Marcel Marceau

Mime’s brief spell in the mainstream.

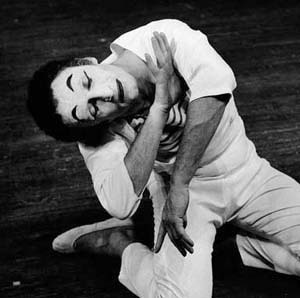

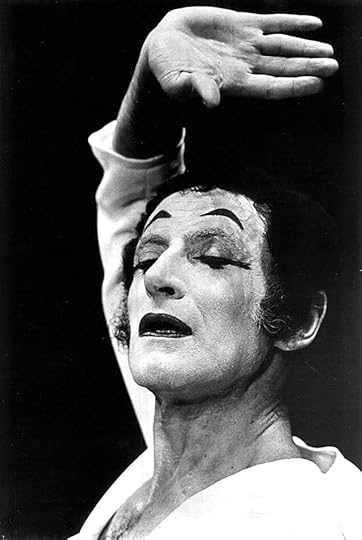

A 1974 publicity photo of Marcel Marceau.

At seven years old, before he is called Marcel Marceau—he was born Marcel Mangel—his father, a butcher with a fine voice, takes him to the cinema in Strasbourg. The film is City Lights. A heavy curtain in the cinema pulls back as the lights go down. He sits next to his father, his shoes dangling, the seat and the velvety darkness huge around him.

Music. On the screen: a title; credits; grand municipal buildings; a crowd of people made of blacks, whites, and greys. They’re all still, waiting for something. Then comes a line of speech written in curled white letters, and a fat man gesticulating—these are the final days of the silent film era. On the screen, a lady holding flowers pulls a ribbon to the sound of a trumpet fanfare, unveiling three giant stone figures. And there is Charlie Chaplin, horizontal, asleep across a giant stone lap. He stretches a leg upward, itches it, yawns. In the crowd, chaos; Chaplin sits up, grabs his cane, tips his bowler hat, tries to wriggle off the sculpture, and gets stuck. He fills the screen, the size of three Marcels.

When the butcher looks down, he sees Marcel’s eyes wide open in wonder, an expression the boy will mime often in years to come when he is the entertainment, being watched by rows of faces in theaters around the world.

The butcher’s son begins to practice Chaplin’s walk, borrowing his father’s trousers and cane to waddle down the streets in their neighborhood. He learns Chaplin’s slapstick routines, finds the timing. At his aunt’s summer house he puts on performances, miming famous stories: Robinson Crusoe, Robin Hood, Chaplin’s Little Tramp.

* * *

His childhood is interrupted by war. When the German troops advance on Strasbourg, the butcher’s family have two hours to pack up and leave home; they flee to the Dordogne, where Marcel and his brother join the resistance movement. Marcel is a talented illustrator: he uses red crayon and ink to alter the identity cards of Jewish youths so they appear too young to be sent to labor camps. (Later, wanted by the Gestapo, he and his brother will forge their own cards, changing their last name to Marceau in tribute to General Severin-Marceau-Desgraviers, a French Revolutionary.) He poses as a scout leader to smuggle groups of children to the Spanish border and over the Alps to Switzerland.

In a forest near Limoges, on a summer afternoon toward the end of the war, he and a companion enter a sunlit clearing and find themselves face to face with a unit of German soldiers—thirty men and an officer. Boots, breeches, pointed collars, thirty-one helmets, thirty-one pairs of eyes looking out from beneath. Marcel assumes the role of the advance guard of a larger French regiment, puffs his chest, looks squarely back at the Germans, and commands them to surrender their weapons. They do.

* * *

Marceau studies at the School of Dramatic Art in Paris under Étienne Decroux, the inventor of corporeal mime. Decroux is the first to formalize the art of mime for teaching; he has a grammar of movement. Two hundred and fifty positions for the hand. One hundred and eight inclinations for the head. His students spend three months mastering the technique of walking in place. Their faces covered, they learn to convey every emotion through the body. Decroux’s pupils mime humanity in the abstract, like the statues of Rodin: the Lover, the Thinker, the Fighter.

But Marceau, still preoccupied with Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, invents a character who combines Chaplin’s movements with the look of a harlequin—a white face, a crumpled top hat with a red flower poking out from the top, white tights, ballet plimsolls, eyebrows painted halfway up the forehead. A face that reveals everything. His creation, “Bip,” is as innocent as Chaplin’s Little Tramp, as clumsy as Harpo Marx, as deft as Buster Keaton—and named after Pip, of Great Expectations. There is something of the Dickensian orphan about him. Every movement is infused with a kind of naiveté.

Decroux, a purist, disapproves; this characterization is closer to pantomime than corporeal mime. This is populism, he thinks, a debased cabaret form of that which should always strive toward abstraction. He dismisses Marceau’s creation as raccourci, a shortcut—Marceau is too eager to entertain.

And this is true. Marceau has grown up on the slapstick of Hollywood comedies; he wants humor and pathos in his work, and for humor and pathos, you need character. An audience can’t connect with abstraction. Their hearts won’t go out to a statue, no matter how perfect it is.

Marceau in 1963. Photo: Erling Mandelmann.

Onstage as Bip, Marceau mimes his way through every possible human scenario. Bip Gets Married. Bip Travels by Train. Bip Goes to a Cocktail Party. Bip Hunts Butterflies. Bip’s rectangular face contorts with surprise or horror or wonder. When Marceau depicts the four ages of man, it is said that “he accomplishes in less than two minutes what most novelists cannot do in volumes.” Audiences fill theaters to watch Marceau’s bizarre alter ego lean on invisible walls, dance with invisible partners, fall in love with empty spaces on the stage. Mute and scrawny, with wiry reddish hair and bristling sideburns, Marceau is still somehow a source of empathy. It’s because of wordlessness: “You don’t laugh or cry in English or French,” he says. “Bip is allowed to go anywhere and dream many dreams.”

* * *

When Bip traps the butterfly in his hands, he holds them out to the audience. Slowly, he draws back one hand to reveal it. And his other hand becomes the butterfly; his fingers twitch and tremor.

In Bip the Lion Tamer, he leaps through the hoop himself. It frames his head and chest. He roars like the MGM lion.

Bip climbs the stairs and becomes the staircase.

He walks headlong into the wind and the audience perceives it as a physical force, pushing his body into strained shapes.

Marceau’s body is trained in counterbalance, a mime artist’s technique that creates, on an empty stage, weather, brick walls, flights of stairs, and cages. Propless on a dark stage, Marceau’s clown, in his spotlight, works as words on a page do. The audience looks at shapes made in black and white, reads meaning into them, and makes up the rest.

* * *

But offstage, Marceau talks—continuously. He’s an energetic raconteur, reciting his stories in a raspy French accent, pinning his listener with an intense gaze. He loves to be interviewed. He delivers grand maxims and aphorisms about life and art. “Bip is the romantic and burlesque hero for our time,” he says. “Bip is a modern-day Don Quixote.”

He finds it hard to sit still when he speaks, often leaping up to accompany his points with gestures, his hands fluttering about as if they are talking too. His face contorts and transforms in time with his stories. He speaks five languages and deploys them as he sees fit, without too much concern for grammar. “Never get a mime talking,” Marceau says. “He won’t stop.”

* * *

Marceau teaches his students to breathe silently when they move. When we watch fish in water, he tells them, it’s beautiful because they’re completely silent. Watching silence is like watching through glass. Silence has a musicality, he says.

On stage, the mime can appear subject to altered physical laws. He can defy gravity. Among the dancers who borrow from Marceau are Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn. The dancer and choreographer Roland Petit decrees that all ballet students must train in the art of mime. Zizi Jeanmaire performs mimes with Marceau, dressed in mirror-image white bell-bottoms, a striped top, a squashed hat, and ballet pumps. Michael Jackson is a disciple of Marceau. His moonwalk is a version of “walking against the wind.”

* * *

A 1971 publicity photo.

He feels his advancing age and fears that the art of mime will die with him. It’s a transitory, ephemeral art, he explains, as it exists only in the moment. As an old man, he works harder than ever, performing three hundred times a year, teaching four hours a day. He is named the UN Ambassador for Aging. Five nights a week he smears the white paint over his face, draws in the red bud at the center of his lips, follows the line of his eyelid with a black pencil. And then takes to the stage, his sideburns frayed, his hair dyed chestnut and combed forward, looking like a toupee.

His body is as elastic as ever, but the old suit of Bip hangs loose on him now. Beneath the whitened jawline is a baggy, sinewy neck. With each contortion of his face the white paint reveals deep lines. At the end of his show, he folds in a deep bow and the knobs of his spine show above the low cut of Bip’s Breton top.

He is fond of talking about himself in the third person. “There is only one Marceau.” And this is true: Marceau dies and leaves no heir. He had performed the same sketches for sixty years. There was nothing for other mimes to build on. He inspires only poor imitations. Upon his death, the art of mime steps back out of the mainstream. It becomes a busker’s act—obscure, often mocked.

So all we have is the footage. Fuzzy, flickering recordings of his performances. A solitary figure on the stage in a circle of spotlight. We can see the white face below the battered hat and watch it move, flicking from one emotion to the next as if someone is pressing the controls on a mask. The outfit is oddly creepy. The act seems to take itself so seriously as to be ridiculous. But when the figure climbs the staircase, we feel that he is rising upwards. When he lifts the dumbbell we can sense its weight.

Mave Fellowes is the author of Chaplin & Company. Her stories have appeared in Granta and other publications. She lives in London with her husband and two sons.

In Praise of the Compact Disc, and Other News

A microwaved compact disc. (Also enjoyable: non-microwaved compact discs.) Photo: D-Kuru, via Wikimedia Commons.

Faulkner and Hemingway had a famously snippy rapport—Will was all like, “He has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary,” and Ernie was all like, “If you have to write the longest sentence in the world to give a book distinction, the next thing you should hire Bill Veek [sic] and use midgets”—which makes Faulkner’s one-paragraph review of The Old Man and the Sea all the more surprising in its candor and courteousness. “Time may show it to be the best single piece of any of us, I mean his and my contemporaries.”

The case for compact discs, which are, at this juncture, the least hip medium in music: “There’s a lot of pressure in our culture right now to essentially imagine CDs out of existence … CDs currently exist in a cultural no-man’s-land recently defined by singer-songwriter Todd Snider as ‘post-hip, pre-retro’—the format is passé, but not so passé that it qualifies for reclamation.”

“No matter how many buildings, spacecrafts, and sentient robots Michael Bay explodes, the director can’t seem to get any respect.” So why do they perform so well at the box office, and what, exactly, motivates Bay’s style? “This video may at least help his detractors articulate their distaste with a greater degree of specificity.”

The artist Mark Dorf’s new series, “Axiom and Simulation,” attempts to illustrate how “the human race is constantly recording data and transforming elements of our physical surroundings into abstracted and non-physical calculations.”

Offices across the land are under the thumb of that insidiously vague dress code, corporate casual. “No one was quite sure what corporate casual meant. We googled it. The gist of every article is that no one knows what corporate casual is.”

July 8, 2014

A Glorious Figure of Young Manhood

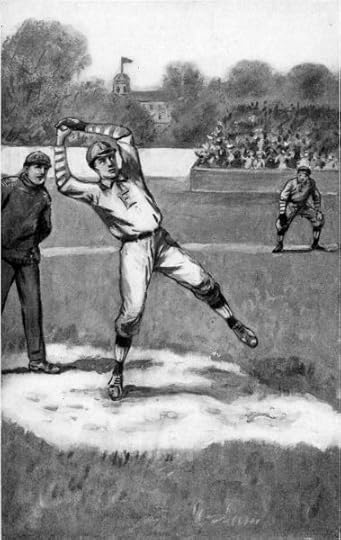

“HE WAS A GLORIOUS FIGURE OF YOUNG MANHOOD”

“IT DARTED TOWARD THE PLATE, BREAKING INTO A WIDE OUTCURVE”

“IT WAS THE LONGEST HIT THAT EVER HAD BEEN MADE ON THE POLO GROUNDS”

“JOE CAUGHT IT SQUARE ON THE END OF THE BAT”

“JOE WAS DOING GOOD WORK”

“THE NEXT MOMENT THE HORSEHIDE WENT SPEEDING TOWARD THE PLATE”

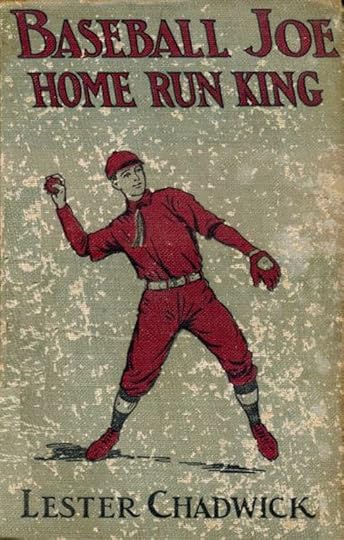

If baseball remains, however tenuously, our national pastime, then Joe Matson, the eponymous hero of Lester Chadwick’s Baseball Joe series, remains our all-American man: an “everyday country-boy” with a can-do attitude, an unimpeachable sense of right and wrong, and a fucking cannon-arm. Chadwick’s sequence of boys’ novels, published from 1912 to 1928, follows Joe on a Horatio Alger–esque journey from small-town schoolyard star to World Series slugger. Spoiler alert: Joe wins. Joe always wins.

With their cheery illustrations and gee-whiz spirit, the Baseball Joe novels emblematize a brand of wish fulfillment that stands at a far remove from the young-adult fiction of today: there’s no dystopia here, nor even a whiff of the supernatural, unless you count Joe’s otherworldly batting average. What we have instead is the distillate of dozens of summers spent dreaming in baseball diamonds, redolent not of beer and nuts but of Wonder Bread and whole milk and Jerry Mathers as the Beaver.

Or so it seems. Turns out the Baseball Joe books had some dark subplots, though you’d never know it to look at their publisher’s catalog, which supplies breathless titles with curiously terse synopses:

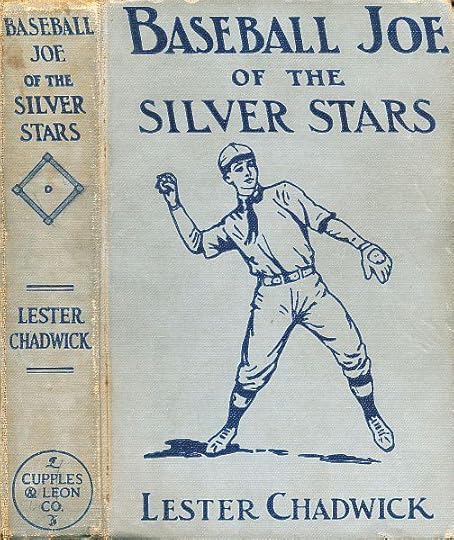

BASEBALL JOE OF THE SILVER STARS

or The Rivals of Riverside

Joe is an everyday country boy who loves to play baseball and particularly to pitch.

BASEBALL JOE ON THE SCHOOL NINE

or Pitching for the Blue Banner

Joe’s great ambition was to go to boarding school and play on the school team.

BASEBALL JOE AT YALE

or Pitching for the College Championship

Joe goes to Yale University. In his second year he becomes a varsity pitcher and pitches in several big games.

BASEBALL JOE IN THE CENTRAL LEAGUE

or Making Good as a Professional Pitcher

From Yale college to a baseball league of our Central States.

BASEBALL JOE IN THE BIG LEAGUE

or A Young Pitcher’s Hardest Struggles

From the Central League Joe goes to the St. Louis Nationals.

BASEBALL JOE ON THE GIANTS

or Making Good as a Twirler in the Metropolis

Joe was traded to the Giants and became their mainstay.

BASEBALL JOE IN THE WORLD SERIES

or Pitching for the Championship

What Joe did to win the series will thrill the most jaded reader.

Fortunately for us, Tim Morris, of the University of Texas, has compiled a guide to the Baseball Joe books as part of a study of juvenile baseball fiction—a once-booming subgenre. And so we come to discover the sensational undertones of Silver Stars, in which “Joe foils some intellectual pirates who are intent on stealing Mr. Matson Sr.’s patents for a new kind of corn reaper”; In the Big League, in which “Joe is at one point chloroformed, kidnapped, and set adrift in the marshes of New Jersey”; and Champion of the League, in which “shameless confidence men try to get Joe to throw the pennant … when Joe turns them down, the con men commission a mad scientist to invent a ray gun that will drain the power from Joe’s pitching arm.” What’s this? Slider-pitching, dinger-hitting Joe is more than a mere sportsman. He’s a kind of also-ran action hero.

For adrenaline junkies like Baseball Joe, too much is never enough. That’s the dark side of the all-American fantasy—it’s not sufficient for a young man to content himself with immense athletic talents and an unlikely trajectory toward major-league superstardom. This is America, god damn it! We need more! He must also stop patent thieves, survive involuntary anesthetization in the Garden State, and thwart mad scientists for hire.

These passages, alternately charming and depressing, are the best parts of the Baseball Joe books; there are any number of dubious scenarios in which Joe’s athletic prowess is the only thing that can save the day. For a quick sample, look to the purple prose of On the School Nine, wherein it falls to Baseball Joe to save a man in a burning factory, “perched on the ledge of what had once been the clock tower,” by pitching him a ball of cord:

Joe hesitated a moment. Everything would depend on his one throw, because there was no chance to get another ball of cord, and if this one went wide it would fall into the fire and be rendered useless.

The fire was increasing, for all the chemicals in the tank on the wagon had been used, and no fresh supply was available. Below the tower on which the man stood, the flames raged and crackled. Even the tower itself was ablaze a little and at times the smoke hid the man from view momentarily …

“He’ll never do it,” murmured Hiram Shell.

“If he does he’s a better pitcher than I’ll ever be,” admitted Frank Brown.

Suddenly Joe threw. The white ball was plainly visible as it sailed through the air, unwinding as it mounted upward. On and on it went, Joe, no less than every one in the crowd, watching it with eager eyes. And as for the man on the tower he eagerly stretched out his hands to catch the ball of cord, on which his life now depended …

Straight and true it went, as swift and as direct a ball as Baseball Joe had ever delivered. Straight and true—on and on and then—

Into the hands of the anxiously waiting man went the ball of cord. Eagerly he clutched it, while the crowd set up a great cheer.

“That’s the stuff!” yelled a man in Joe’s ear. “You sure are one good pitcher, my boy!”

And this is why baseball must remain a vital aspect of American culture; no child raised on soccer or football could be expected to chuck a life-saving fastball.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers