The Paris Review's Blog, page 681

July 23, 2014

Read Everywhere, Part 5

Benjamin Louter reads The Paris Review in a kayak off Vancouver Island.

Celebrate summer—and get summer reading, all year round—with a joint subscription to The Paris Review and The London Review of Books.

The Paris Review brings you the best new fiction, poetry, and interviews; The London Review of Books publishes the best cultural essays and long-form journalism. Now, for a limited time, you can get them both for one low price, anywhere in the world.

Tell us where you’re reading either magazine—or both! Share photos from around the world with the hashtag #ReadEverywhere.

The World’s Most Average Typeface, and Other News

Z, from BIC’s Universal Typeface Experiment.

On the Booker longlist: Joshua Ferris, Joseph O’Neill, Richard Powers, Siri Hustvedt, Howard Jacobson, David Mitchell, David Nicholls, and others. Notably excluded: Donna Tartt.

Earlier this month came news of Charlotte and Branwell Brontë’s tiny books; now it’s the Brontë sisters’ school progress reports. In the early nineteenth century, a minister at Cowan Bridge noted that Charlotte “writes indifferently … knows nothing of grammar, geography, history, or accomplishments.”

Do you seek a bland font, a middling font, a dutifully average font? Try the Universal Typeface, “a constantly evolving, algorithmically produced font created by averaging hundreds of thousands of handwriting samples submitted to BIC’s website. Anyone with a touchscreen can help shape the Universal Typeface by linking their phone or tablet to the website and writing directly on the touchscreen—the lettering is quickly transferred to the Universal Typeface algorithm. As of this writing, more than 400,000 samples have been collected from around the world, and the resulting alphabet is … well, sort of boring.”

Wallace Shawn discusses playwriting and his new take on Ibsen’s The Master Builder : “If a man can presume to make a list of men who contributed to the feminist view of life, you’d have to put Ibsen at the head of the list. But he’s laying out on the table some of the worst male fantasies. I mean, he was a very daring writer, and he dared to be sort of sickening. He dared to create these characters who were sort of dreadful.”

“The jukebox musical can be an embarrassing phenomenon: a living, breathing pop-music wax museum. It can be pandering and disingenuous, fostering a dynamic that the Times has called ‘ovation-by-coercion.’ It can repackage your happiest memories as a Vegas revue … Our instinct is to sigh about it, but we shouldn’t. The form is evolving.”

July 22, 2014

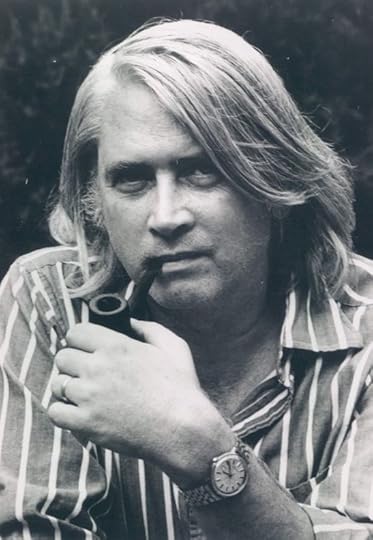

Thomas Berger, 1924–2014

The Times has reported that Thomas Berger died a little more than a week ago, on July 13, just shy of his ninetieth birthday. Berger wrote twenty-three novels, the best-known of which is 1964’s Little Big Man, a western picaresque that was later adapted into a movie starring Dustin Hoffman.

The Times obit finds a through-line in his work: “the anarchic paranoia that he found underlying American middle-class life.” “It was Kafka who taught me that at any moment banality might turn sinister, for existence was not meant to be unfailingly genial,” Berger said in a rare interview. He enjoyed a cult readership throughout his prolific career, and his books bear blurbs from the likes of John Hollander and Henry Miller; in 1980, The New York Times Book Review proclaimed, “Our failure to read and discuss him is a national disgrace.”

Today, his most outspoken advocate is probably Jonathan Lethem, who discusses an early (and démodé) fondness for Berger in his Art of Fiction interview: “When I got to Bennington, and I found that Richard Brautigan and Thomas Berger and Kurt Vonnegut and Donald Barthelme were not ‘the contemporary,’ but were in fact awkward and embarrassing and had been overthrown by something else, I was as disconcerted as a time traveler.” And Lethem effused in an essay for the Times a few years back,

Berger’s books are accessible and funny and immerse you in the permanent strangeness of his language and attitude, perhaps best encapsulated by Berger’s own self-definition as a “voyeur of copulating words.” He offers a book for every predilection: if you like westerns, there’s his classic, “Little Big Man”; so too has he written fables of suburban life (“Neighbors”), crime stories (“Meeting Evil”), fantasies, small-town “back-fence” stories of Middle American life, and philosophical allegories (“Killing Time”). All of them are fitted with the Berger slant, in which the familiar becomes menacingly absurd or perhaps the absurd becomes menacingly familiar.

Berger, who spent most of his life diligently removed from public life, seemed to submerge himself in a goulash of genre fiction, emerging every few years with something new and piquant. The variety of his books is borne out by their incredible first-edition jacket art, some of which I’ve gathered above—vibrant pastiches of everything from noir to Arthurian legend, many of them with a unabashed lowbrow strangeness that’s anathema to jacket designers today. As the author himself put it: “I am peddling no quackery, masking no intent to tyrannize, and asking nobody’s pity.”

The Crack-Up

Image via Markscheider/Wikimedia Commons

For longer than I care to admit, I have been unable to scroll down on my computer. This is only the latest in a series of laptop-related inconveniences, but, given the nature of my employment, is something of a problem. If you manage to catch the scrolling bar to the far right of the screen, you can generally navigate okay, but if you relax your vigilance for a moment and move your cursor, that option is closed, and it is necessary to refresh the screen. At least, that’s the only way I know how to do it.

I have lived without video and Flash capacity for some five months now, and it has been a rich, full life, but this scrolling situation seems untenable. I am going to have to go to the Genius Bar, a prospect I dread.

It’s not that I mind the trip, the wait, or even the well-deserved condescension of the Geniuses. At least this time around, there is no varicolored crayon wax mysteriously covering my computer, leading me to mumble some absurd, half-formed lie that implied I either had small children or was a preschool teacher. I’m just terrified that they’re going to tell me the computer can’t be saved, that the scrolling is indicative of a more serious—terminal—illness. (From this you might imagine how conscientiously I deal with actual medical issues.)

I’m not quite so far gone as to be blind to the madness of this behavior—like one of those people on Hoarders who sort of knows he has a lot of stuff, but clearly doesn’t really believe it’s a problem. I have enough sanity to be humiliated, and the final words of “These Days” drone endlessly in my head:

Please don’t confront me with my failures / I had not forgotten them.

In such moments, I feel a certain futility, as if to do something normal and efficient might imply that I was, in fact, a normal and efficient person. Which, of course, would be a sham. And so the self-doubt fulfills itself.

In my defense, it’s next to impossible to make an appointment at the Genius Bar when you can’t navigate your computer screen. It’s a catch-22 they really ought to address. In fact, the more I think about it, this really isn’t my problem at all. I think it’s institutional. It hints at something deep.

Blunt the Edge

Detail from the cover of The Baffler’s eighth issue; art by Archer Prewitt.

The Baffler, which has probably the best slogan of any magazine in history—“the Journal that Blunts the Cutting Edge”—has made all of its back issues available for free online: required reading for anyone interested in the tenor of criticism and analysis in the nineties and early aughts, if that’s what we’ve decided to call them.

For starters, I recommend Tom Vanderbilt on SKYY vodka’s ridiculous original campaign, which was predicated on the myth that it was “hangover free” (“built on that distinctly American quest to find magic formulas to indulge more and suffer less”); or Kim Phillips-Fein’s “Lotteryville, USA,” a powerful screed against the ills of the lottery as an institution; or Terri Kapsalis’s “Making Babies the American Girl Way,” a terrifying meditation on multicultural dolls, artificial insemination, and designer babies; or, perhaps my personal favorite, Steve Albini’s “The Problem with Music,” a terse, caustic critique of the record industry at the height of yuppie-ism and major-label excess. Its scorched-earth opening:

Whenever I talk to a band who are about to sign with a major label, I always end up thinking of them in a particular context. I imagine a trench, about four feet wide and five feet deep, maybe sixty yards long, filled with runny, decaying shit. I imagine these people, some of them good friends, some of them barely acquaintances, at one end of this trench. I also imagine a faceless industry lackey at the other end, holding a fountain pen and a contract waiting to be signed.

Nobody can see what’s printed on the contract. It’s too far away, and besides, the shit stench is making everybody’s eyes water. The lackey shouts to everybody that the first one to swim the trench gets to sign the contract. Everybody dives in the trench and they struggle furiously to get to the other end. Two people arrive simultaneously and begin wrestling furiously, clawing each other and dunking each other under the shit. Eventually, one of them capitulates, and there’s only one contestant left. He reaches for the pen, but the Lackey says, “Actually, I think you need a little more development. Swim it again, please. Backstroke.”

And he does, of course.

If arch anticapitalist rhetoric and scatological takedowns of corporate media aren’t your cuppa, The Baffler publishes a nice variety of fiction and poetry, too. Have at it.

The Greatest Artist in the Whole Wide World

A portrait of the author by his mother, Louise Oliver.

Louise Oliver, Edgar, December 14, 1963

Louise Oliver, Helen at Seventeen or So

Louise Oliver, Untitled (January sketch)

Louise Oliver, Still Life with Glasses

One of our favorite places to play, all throughout my childhood, was in cemeteries. We would go get fried chicken at the Woolworth’s on Broughton Street and go with our sketch pads to the Colonial Cemetery to picnic atop the family vaults that were all shaped like gigantic brick bedsteads. Helen and I loved to climb on these strange bed-shaped vaults and to lie there on the gently curved bellies of the tombs and play at being dead. And while we played, Mother drew in her sketch pad.

At the very back of the cemetery was a playground with old, rusted iron swings that shrieked when you swung in them. Helen and I loved to swing high and make the swings shriek mournfully—the cry of our flight. On the other side of the brick wall, overlooking the playground, rose the Savannah jailhouse—a tall old building with a tower topped by a red onion dome. High up in the jailhouse wall were dark arched windows where you could sometimes see the silhouettes of men’s heads—the prisoners watching us as we swung.

“You’re the greatest artist in the whole wide world, Mother. You’re also the best, funnest, most beautiful Mother in the whole wide world. And you cook such good food too.”

Mother made us say that to her over and over again—every day. And I think we said it sincerely. Mother almost never cooked—but when she did, what she made was always luscious. And I think Mother was a great artist. There is an innocence to Mother’s work that is like a form of revelation.

Over the years of our childhood, Helen and I were to become Mother’s most trusted and devoted encouragers and critics. Mother would call us in from the backyard to examine whatever painting she was working on. We would make our pronouncements with great authority.

“It’s finished, Mother. Don’t do another thing to it. If you touch it again, you’ll ruin it.”

“But isn’t it a bit sketchy?”

“You may think it sketchy, Mother. But that’s part of its power—its sketchiness. If you touch it again, you’ll ruin it. You know what happened to the last painting?”

“The one in oils?”

“Yes, Mother. We told you it was finished. But you didn’t listen to us. And look what happened.”

Mother: “It got all muddy. I ruined it.”

Wee all three look at the painting.

Mother: “So you’re sure it’s finished?”

Edgar: “Yes, Mother.”

Helen: “Absolutely, positively certain.”

Then we all three study the painting for some minutes.

Helen: “It’s a masterpiece, Mother.”

Edgar: “Yes. Truly a masterpiece.”

Helen and Edgar together: “You’re the greatest artist in the whole wide world, Mother!”

Mother: “What else?”

Helen and Edgar together: “You’re also the best, funnest, most beautiful Mother in the whole wide world! And you cook such good food too!”

And then we kiss Mother thirteen times—at the end shouting out jubilantly all together, “Thirteen!”

This piece originally appeared in The Folio Club ’s drawing issue.

Edgar Oliver is a writer and actor. His one-man show Helen & Edgar (2012) featured some of these drawings, all of which are by his mother, Louise. Edgar’s newest theatrical work, In the Park, was performed at Axis Theater this past spring.

Our Office Plants, Ourselves, and Other News

Polly Brown photographs plants in offices. Photo via The New Yorker; plant also via The New Yorker.

Coming soon to the two-euro coin: Tove Jansson’s face. How can you get one? “ ‘Some collectors consider it important to obtain the coin from circulation, but it is easier to purchase the special coin in polished proof quality from numismatic shops or the Mint of Finland online shop,’ says Mint of Finland CEO Paul Gustafsson.”

Bertrand Russell: bright guy and all, but was his pacifism really so logically rigorous? “The peace agenda of Russell and his followers was always based on the assumption that war is simply a euphemism for the madness of state-sponsored mass murder, and that we could prevent it by standing up for moral and political sanity … But the paths to war are paved not with malice but with righteous self-certainty. People who choose to participate in military action are more likely to be altruists than egotists.”

How should you explain what your novel’s about? Not like this: “This was the story of a young guy, from a town, with a family, with a handful of familiar issues, going back to that town.”

The photographer Polly Brown “has spent the past year documenting the plants that bloom in the headquarters of Louis Vuitton, A.T. & T., Nike, Vogue, and even The New Yorker … Brown’s idea was to present the office plant as a representation [of] our ‘biophilic desires.’ ”

In 2002, radio producers interviewed “New Yorkers who were among the last—and in some cases, the very last—to hold jobs in industries that were dying … They came up with seven people—a Brooklyn fisherman, a water-tower builder, a cowbell maker, a knife-and-scissor grinder, a lighthouse keeper, an old-fashioned bra fitter, and a seltzer man.” The interviews are now online.

July 21, 2014

Under the Volcano

John Gardner in 1979. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

I think that the difference right now between good art and bad art is that the good artists are the people who are, in one way or another, creating, out of deep and honest concern, a vision of life in the twentieth century that is worth pursuing. And the bad artists, of whom there are many, are whining or moaning or staring, because it’s fashionable, into the dark abyss. If you believe that life is fundamentally a volcano full of baby skulls, you’ve got two main choices as an artist: You can either stare into the volcano and count the skulls for the thousandth time and tell everybody, “There are the skulls; that’s your baby, Mrs. Miller.” Or you can try to build walls so that fewer baby skulls go in. It seems to me that the artist ought to hunt for positive ways of surviving, of living.

That’s John Gardner, from his Art of Fiction interview, which The Paris Review published in 1979—three years before Gardner died in a motorcycle accident. As far as lines in the literary sand go, this one seems defensible enough: make salutary art, wall off the volcano, protect the crania of your babies, et cetera. But here Gardner has given us the distillate of what had been, a few years earlier, a very controversial opinion; he’s paraphrasing his thesis from On Moral Fiction, a polemical book of criticism in which he took to task nearly every prominent American writer, pissing off a good number of them in the process. As Dwight Garner wrote a few years ago, “It wasn’t Gardner’s thesis, exactly, that made him enemies. It was the way he indiscriminately fired buckshot in the direction of many of American literature’s biggest names.”

Pynchon? Too inclined to “winking, mugging despair.”

Updike? “He brings out books that don’t say what he means them to say. And you can’t tell his women apart.”

Barthelme? Merely a disciple of “newfangledness.”

And the whole New Yorker crowd? Too into “that cold, ironic stuff … I think it’s just wrapping for their Steuben glass.”

If you’re thinking that picking fights is a pretty poor way of seeding one’s literary philosophy, you’re completely correct. As Per Winther, the author of The Art of John Gardner, has written, “One cannot help but think that Gardner’s cause would have benefited from less stridency of tone … What Gardner risked in couching his arguments in such bellicose terms was a hasty dismissal of his book and all its views.”

And so he was, at least in certain circles, hastily dismissed. In the Times Magazine, Stephen Singular wrote a profile in which he invited the aggrieved parties to respond to Gardner’s appraisals. Updike, by my lights, gets the best rejoinder: “‘Moral’ is such a moot word. Surely, morality in fiction is accuracy and truth. The world has changed, and in a sense we are all heirs to despair. Better to face this and tell the truth, however dismal, than to do whatever life-enhancing thing he was proposing.”

Still, aside from the ambiguity of “a vision of life … that is worth pursuing,” there’s plenty to recommend itself in Gardner’s idea of good art, especially as he expresses it in that Art of Fiction quotation—it reminds, in its elegance, its humor, and its ethical heft, of David Foster Wallace’s “E Unibus Pluram,” which argued, more than twenty years later, for fiction writers “who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction.” In a 1993 interview with Larry McCaffery, Wallace channeled Gardner even more directly:

Look man, we’d probably most of us agree that these are dark times, and stupid ones, but do we need fiction that does nothing but dramatize how dark and stupid everything is? In dark times, the definition of good art would seem to be art that locates and applies CPR to those elements of what’s human and magical that still live and glow despite the times’ darkness. Really good fiction could have as dark a worldview as it wished, but it’d find a way both to depict this world and to illuminate the possibilities for being alive and human in it.

And yet in the next line, Wallace qualified his statement: “I’m not trying to line up behind Tolstoy or Gardner.” Isn’t he, though, to some degree? I understand the distinction—undoubtedly Gardner and Wallace differ on the finer points of what constitutes “illuminat[ing] the possibilities for being alive and human”; Wallace is very careful not to use the word moral, and he at least had the good sense to endorse Barthelme—but it seems specious of him to have denied any sort of connection to that tradition. Then again, of course he’d want to distance himself. Gardner had, in making straw men of so many talented writers, ensured that his feelings on art were marked with a kind of biohazard sticker. The only way to champion his philosophy was at a far remove.

Beards

An early illustration of Saint Wilgefortis.

If you had asked me two days ago if there existed any Catholic-themed YouTube video stranger than the one where G. K. Chesterton battles a cartoonishly evil Nietzsche, I would have said, “Of course not.” But that was before I saw this group of French feminists in beards paying tribute to Saint Wilgefortis.

Wilgefortis is described by the Catholic Encyclopedia as “a fabulous female saint known also as UNCUMBER, KUMMERNIS, KOMINA, COMERA, CUMERANA, HULFE, ONTCOMMENE, ONTCOMMER, DIGNEFORTIS, EUTROPIA, REGINFLEDIS, LIVRADE, LIBERATA, etc.”; her attributes are listed as “bearded woman; depicted crucified, often shown with a small fiddler at her feet, and with one shoe off.” Considered a “pious fiction”—that is, a sort of unofficial folktale—she enjoyed popularity throughout Europe. Before the Church removed her commemoration in ’69, July 20 was her feast day.

Though her cult is thought to date to the fourteenth century, concrete details are sparse: generally, Wilgefortis is described as a young, Christian, sometimes Portuguese, occasionally septuplet princess who, rather than marry a pagan against her will, prayed for disfigurement. Her prayers were answered in the form of a beard. Her father, furious with this development, had her crucified. Nowadays, it’s thought that the Wilgefortis story—as well as the related fiddler/shoe legend—evolved from a misinterpretation of the famous Volto Santo crucifixion sculpture in Lucca, Italy. The art historian Charles Cahier wrote,

For my part, I am inclined to think that the crown, beard, gown, and cross which are regarded as the attributes of this marvelous maiden (in pictorial representations), are only a pious devotion to the famous crucifix of Lucca, somewhat gone astray. This famous crucifix was completely dressed and crowned, as were many others of the same period. In course of time, the long gown caused it to be thought that the figure was that of a woman, who on account of the beard was called Vierge-forte.

Although the cult was vigorously debunked in the Gothic period, several famous representations still exist—and she is, after all, a distinctive figure. Wikipedia describes “an especially attractive carving in the Henry VII Chapel of Westminster Abbey of a beautiful standing Wilgefortis holding a cross, with a very long beard”; another “very lightly bearded, on the outside of a triptych door by Hans Memling”; and, at the church of Saint-Étienne in Beauvais, a sculpture in which she is “depicted in a full blue tunic and sports a substantial beard.”

Whither the French feminists, you ask? Wilgefortis is the patron of tribulations, with a special focus on those women who wish to be disencumbered from abusive spouses. If you wish to commemorate Encumber (that’s her English name) without any social overtones, and you happen to be in London, you’re in luck, or you would’ve been yesterday. According to the page of a beard-enthusiast group called the Capital Beards,

The Capital Beards will next meet along with the rest of The British Beard Club on July 20th for St. Wilgefortis’s feast day. St. Wilgefortis is a notably bearded saint, and so we try to meet up on her feast day every year.

Our venue will be the Buckingham Arms on Petty France. A pub notable for being one of only two in London to have been in every edition of CAMRA’s Good Beer Guide.

As normal we should be there from about Midday.

Recalcitrant Language: An Interview with Ottilie Mulzet

Art from the first Hungarian edition of Seiobo járt odalent, or Seiobo There Below.

Translators of the Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai are a daring few, but they tend to win awards. This year’s Best Translated Book Award went to Ottilie Mulzet for the first English translation of Seiobo There Below , a dazzling, far-ranging novel even by Krasznahorkai’s standards. At 451 pages, the novel took Mulzet three years to translate; it required familiarity with everything from the terminology of Russian icon painting to the existence of Arcade Fire. The story, told in a series of loosely linked episodes, addresses small matters of death, time, divinity, and the transcendence of art. And that’s not to mention the sentences—intricately constructed puzzles designed to disorient and amaze the reader. They can be up to fourteen pages long.

Krasznahorkai is developing a cult following in the English-speaking world—he’s had one for decades in Hungary—and he draws packed crowds at readings. A recent appearance at Columbia University was so crowded that people were turned away. The author read in a dark room with only a pinpoint of light on the manuscript, for dramatic effect.

I caught up with the woman working under the name Ottilie Mulzet—a partial pseudonym, somehow not surprising from an artist affiliated with Krasznahorkai—to find out how she does it, and what else she has in store.

Tell me about your history with Krasznahorkai. How did you become his translator? How do you work with him?

Before I ever met him, I translated one of the stories, “Something is Burning Outside,” from Seiobo There Below. It appeared on the Hungarian literature website www.hlo.hu, and in June 2009, it was picked up by the Guardian for a series of translated short stories from Eastern Europe twenty years after 1989. I met Krasznahorkai briefly sometime around then. We corresponded, and I mentioned I’d be willing to take on the translation of Seiobo. Krasznahorkai was understandably a little hesitant at first, given the extraordinary complexity of the work. But I translated Animalinside, which was met with a very positive reception and went into a second printing fairly quickly. The following spring, I sent a sample chapter of Seiobo to New Directions.

Krasznahorkai and I communicate a lot by email. If I have any questions at all, he is absolutely wonderful about answering them. We communicate for the most part in Hungarian. There are times when he issues explicit instructions. For example, he didn’t want any of the foreign words in Seiobo italicized, and I could understand why, because they’re even more disorientating when they’re seemingly innocently integrated into the text. For me that was a pretty radical gesture.

What are the strengths and particularities of Hungarian as a language, and what challenges does it present to translate it into English?

I feel extremely close to Hungarian as a language. I love the sound of it, I love how it works grammatically, I love the vocabulary, the astonishing mishmash of words from so many different languages, I love what writers can do with it. Hungarian is an agglutinative language with vowel harmony—it has seemingly endless suffixes and amazing possibilities for compound words, and it has absolutely flexible word order, depending on what you want to emphasize in the sentence. And I would certainly mention the unbelievable elasticity of Hungarian—it’s like a rubber band. It can expand and expand, until you think, Well, this rubber band is going to break at any moment now, or it can shrink into just a few sparse words, where all the most important parts are left out and you just have to know.

English, despite how global it is, is a lot less flexible. Maybe the kind of English that’s spoken in the Indian subcontinent—where it’s partially subjugated to the tendencies of Hindi—would be a more suitable English for translation from Hungarian, but I have to work with the language I know the best. You have to struggle to make sure the sentences don’t seem too jam-packed with information, and yet, when there’s some pretty serious elision going on, you have to test the boundaries of English, with its rigid subject-verb-object structure and having to have all your indicators in place. Hungarian can look like just a splash of ink on the page. There are sentences—or, in Krasznahorkai’s case, subclauses—of just two or three words. I’m intrigued by all of this elision, and fascinated by the problem of conveying it in a recalcitrant language like English—just trying to get English to do something it’s not really meant to do. English today is the global language of commerce and trade, so while it’s dominant, it’s also in some respects deeply impoverished. It desperately needs these transfusions from other languages.

What’s being lost reading Krasznahorkai in English translation, in terms of the texture of the language?

Hungarian readers—I mean the kind of Hungarian readers who read serious literature—have a much higher tolerance for the extreme grammatical complexity of some of these sentences, not to mention the length. I tried to preserve as much of the complexity as I could—there are parts of the book, even in the original, where the reader can feel like he or she is lost in a maze, and I wanted to keep that.

There are a few scattered short passages that read like poems in the original, and in some cases, I couldn’t preserve the sound. One example that comes to mind is the phrase “rízs és víz, rízs és víz”—“rice and water, rice and water”—which Master Inoue Kazuyuki describes as the only food in the house when his family was going through a period of great impoverishment. The repeated long i in that phrase, combined with the final sibilants, creates an indelible sonic impression that I don’t think can come through in the English, although the repetition re-creates, I hope, the strangely desperate humor so typical of Krasznahorkai.

Are the long sentences more difficult to translate than the short sentences?

Are the long sentences more difficult to translate than the short sentences?

It actually depends on what kind of long sentence it is. In some of the long sentences, there’s a pattern of one piece of new information following another. Here, the danger is that the sentence in English can easily sound like a run-on. I would never insert a full stop where there isn’t one in the original, because for me these sentences are like rivers, and if you place a full stop where there isn’t one in the original text, it’s like you’re damming up the river.

But those kinds of sentences are actually relatively easy, especially compared to those where Krasznahorkai is deliberately exploiting the extraordinary elasticity of Hungarian grammar, so that, for example, a diagram of what subordinate clauses are related to would look something like a spider’s web imposed on top of the typeset page. Then there are other long sentences with a kind of running parallel structure—English can tolerate that fairly well.

Some translators claim to be more literal, whereas others take more liberties for the sake of readability. Where would you say you fall on that spectrum?

Sometimes I feel the “literalness—readability” opposition is a little artificial, because there are many ways to transmit the utter strangeness of what you are translating. I really try to convey what I feel is unique about the original, why it wasn’t written in English and perhaps never could be written in English. I want my translation to be something impossible yet extant, something existing on the border of two utterly incompatible worlds, and yet to be a bridge between those worlds. I want the reader of the English version to feel the same shock I felt when reading the original. I don’t want to make it easy or acceptable, or to over-domesticate the text. There is an incredible poetry in the Hungarian language. Sometimes it’s infinitely gentle, sometimes it’s savage poetry.

Once, a long time ago, I was attending an intensive Hungarian-language seminar. Some of the more unusual features of Hungarian grammar were met with comments such as, “Who let these people in?” Whereas other participants confined themselves to more rhetorical questions—“What does this language want?” And the answer came from the instructor, without missing a beat. “Blood, sweat, and tears.” I don’t want blood, sweat, and tears from Krasznahorkai’s English readers, but the absolute otherness of a language like Hungarian immediately puts us in a position of discomfort. Can the translation preserve this discomfort—troubling, weird, yet in the end perhaps edifying and salutary? And in the case of a writer like Krasznahorkai, we’re talking about a writer whose express intention is to discomfit and disorientate his readers. “The dizzying nature of the text”—there is certainly a kind of explicit, readerly jouissance in that.

Do you ever close your laptop for the evening and think, Well, I did a sentence today?

Yes! Sometimes it’s only “I began a sentence,” or “I ended a sentence,”or even just, “I read through a sentence”…

Somewhere into that first six-page sentence, most English-speaking readers of Krasznahorkai probably pause to think, as I did, Wow, who on earth translated this? And then you have this beautiful, mysterious name, Ottilie Mulzet.

The name Mulzet is actually connected to my central European roots—I had a Hungarian grandmother named Mulzet, Luiza Mulzet. I took the name Ottilie because I liked it. It just happens to be the name of one of Kafka’s sisters. Ott in Hungarian means there, so perhaps it also signifies I am the one who is always there, not here …

I began learning Hungarian because I grew up adopted. I didn’t even know there were any Hungarians in my background until I was an adult. I thought, Well, this is one way to know something about the people who were my ancestors on this earth. I began to learn the language out of a kind of intellectual curiosity, but then it really became a kind of addiction.

Ottilie Mulzet. Photo via New Directions

Krasznahorkai fans lament that only four of his novels are translated into English. Do you have your life’s work cut out for you? Do the untranslated titles haunt you?

Two translations haunt me as we speak. One is Destruction and Sorrow Beneath the Heavens, which I’m translating now. It’s literary reportage based on Krasznahorkai’s extensive travels in China, and, if anything, it’s even more relevant today than when it was first published in 2002. The other is The World Goes On, an amazing collection of short stories. George Szirtes, who won the Best Translated Book Award in 2013, also for a Krasznahorkai title, is translating From the North by Hill, From the South by Lake, From the West by Roads, From the East by River, so readers should have at least three more titles to look forward to in the next few years.

Do you have any news or projects coming up?

I’ll be working on Szilárd Borbély’s The Dispossessed, his memoir of growing up in an impoverished village in northeastern Hungary in the late sixties. Perhaps the most talented poet of his generation, Borbély tragically committed suicide in February of this year. He was a very close friend and an incredible person. His death is just an inconceivable loss, leaving behind a huge vacuum in Hungarian and European letters. If I can bring a new English readership to Borbély’s work, I will feel happy—as happy as anyone can feel under such circumstances.

Valerie Stivers is a journalist, writer, and editor; she’s blogging about every book she reads in 2014 at AnthologyOfClouds.com. She is also a reader for The Paris Review.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers