The Paris Review's Blog, page 679

July 29, 2014

Colonized on Every Level: An Interview with Dodie Bellamy

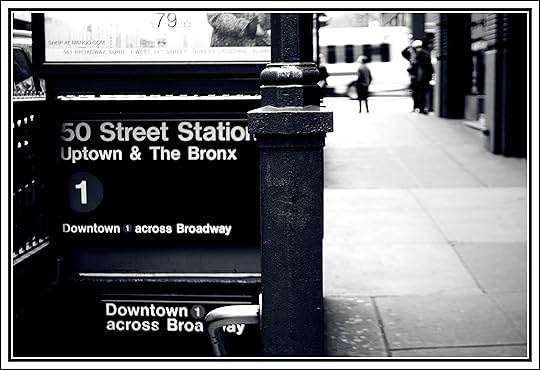

Photo: Ugly Duckling Presse

Dodie Bellamy writes genre-bending works that focus on sexuality, politics, and narrative experimentation, challenging the distinctions between fiction, essay, and poetry. Her methods include radical feminist revisions of canonical works, as in Cunt-Ups (2002) and its follow-up Cunt Norton (2013), which appropriate the “cut-up” technique made famous by William Burroughs; and The Letters of Mina Harker (2004), an epistolary collaboration with the late Sam D’Allesandro, which reimagines Bram Stoker’s Dracula in an AIDS-plagued San Francisco. In her 2004 book Pink Steam, Bellamy explains, “I’m working toward a writing that subverts sexual bragging, a writing that champions the vulnerable, the fractured, the disenfranchised, the sexually fucked-up.”

As an active member of San Francisco’s avant-garde literary scene for the past thirty years, Bellamy is often associated with the New Narrative movement. Before moving to San Francisco in the late seventies, she grew up in the Calumet region of Indiana, studied at Indiana University, and joined a New Age cult. That experience informs her newest book, The TV Sutras , which Norman Fisher has described as “part porno, part memoir (maybe), part spiritual teaching (probably not), [and] part fiction.” Bellamy says she spent five months “receiving transmissions” from her television set, writing brief commentaries on each, which serve as the material for Part One. For example, from #5—“Do you want me to come back to your place? Man and woman in bar. Commentary: Focus on getting back to the basics/beginning anew. Establish a home base you can return to.”

Part Two, “Cultured,” switches into a more familiar form of narrative, but nevertheless refuses to explain itself. At times it seems as though it contextualizes and complicates the sutras in Part One, while at other times the connection seems hidden. In a recent correspondence with Bellamy, we discussed TV Sutras and her history with the New Narrative movement.

You refer to The TV Sutras as a conceptual piece. I’m curious about the ways you see it participating in the current trend of conceptual poetics, or conceptualism in general.

While my writing shares enough concerns with conceptual poetics to be published by Les Figues—poems from Cunt Ups are included in their I’ll Drown My Book anthology, followed by the book length Cunt Norton—The TV Sutras, like the current trend of conceptual poetry, connects with older roots in twentieth-century Conceptual art practices, procedural practices that have been employed since before the surrealists. Procedural strategies have been in vogue ever since I came to poetry in San Francisco in the late seventies—erasure poems, cut-ups, et cetera. I remember very early on going to a reading by Carla Harryman during which she said she “generated” a text, and I was shocked at her use of the word “generated” instead of “wrote.” For me, this was one of those “Dorothy’s no longer in Kansas” moments. Kathy Acker’s use of appropriation has been a touchstone, as well as her conflation of reading and writing. I “generated” the first handful of TV sutras for the Occult issue of 2nd Avenue Poetry, which focused on the intersections between poetry and divinatory practices, particularly rituals that introduce chance. In receiving my sutras through my television, I was reaching back to an ancient tradition of inspired texts—texts that arrive, bidden or unbidden, from a divine/alien elsewhere.

You’ve said elsewhere that “the central problem in The TV Sutras is that of boundaries,” which makes me wonder about the various boundaries being blurred between parts one and two of the book.

The two parts of the book form a symbiotic relationship. Part One is the received text, with mini-commentaries for each sutra. Part Two, “Cultured,” is an extended commentary on the received text as a whole—and the whole notion of who owns meaning. This essay mode provided a convenient container for these disparate parts of my autobiography I’d not been able to figure out how to address before. The whole issue of blurred boundaries in The TV Sutras comes down to the impossibility of separating out self from culture. Is there any part of our being that isn’t to some extent “cultured”? I don’t think so. We are colonized on every level.

Your experience as the member of a cult plays an important part in the second section of the book. In what ways do you see that experience intersecting with the sutras in the first section of the book?

Your experience as the member of a cult plays an important part in the second section of the book. In what ways do you see that experience intersecting with the sutras in the first section of the book?

The sutras are a mystery to me. I don’t feel like I own them, and some of the commentaries I find so groan-worthy that I take on Frankenstein’s relationship to his poor creature, wanting to reject them outright. In writing the “Cultured” section of the book, I was trying to understand and evaluate my sutras. Taken together, are they valid as an inspiration text? How valid is any inspired text? What were the personal and larger cultural vectors from which they sprung? The cult was simply part of the matrix from which the sutras emerged. Ultimately, I wasn’t so much interested in one particular cult, but in the processes of cults and their appeal.

Vulnerability seems key to both sections.

Vulnerability is key to most writing that I’m interested in. Unless the writer totally turns oneself over to their project, allows oneself to be twisted inside out by it, where’s the charge? You end up with a dead writing machine, like the prototypical MFA-workshop short story. I’m not a big fan of irony or cleverness. I always urge students to write to the point of discomfort.

I think you succinctly encapsulate one of the book’s central tensions when you write, “New Narrative Dodie versus New Age Dodie. Can one ever stop embarrassing the other?” For readers who might be unfamiliar, could you explain what you mean by “New Narrative”?

After moving through various poetry scenes in San Francisco, in 1981 I became involved with a small group of mostly gay, male writers who had created New Narrative as a literary movement. The goal was to reset narrative/fiction writing within the theoretical insights learned through their study of contemporary poetry. Language Poetry, and its predilection for literary theory, had taken over the Bay Area writing. I tend to view it as a phase I passed through during my youth, but its influence is still everywhere in my work. I had to work really, really hard to survive in the rigorous intellectual atmosphere of the time. When I was told that I was expected to write essays, to take part in the intense conversations about literature that were going on, I felt this deep sense of dread, not unlike when I was in junior high and my mother announced that I had to start wearing a bra.

While now it’s all the rage to do rituals and be a mystical poet of sorts, back then this would not have flown. So what was I to do about all this degenerate New Age material I was drawn to? When I was writing my first book, The Letters of Mina Harker, I was reading writing-scene-approved theoretical texts, but I was also passionate about all this goddess material and Jungians such as James Hillman and Marion Woodman. The Jungian and the goddess material overlapped, of course. Sylvia Brinton Perera’s Descent to the Goddess was seminal in my creating Mina, my vampire goddess, for it gave me permission to explore a psychic disintegration that terrified me. But I always kept those interests hidden. Recently, in On Contemporary Practice, I published an essay in which I discuss the profound impact Diane di Prima’s Loba—her wolf goddess poems—had on me. This felt liberating. The Loba poems are not well known in my circle, where di Prima is seen as a political Beat poet. It’s too bad so much of the New Age is so dopey. Di Prima’s more spiritual poems have, fortunately, held up really well.

You said earlier that you felt like some of the commentaries in the first section were “groan-worthy,” and then in the second part of the book you raise the issue of embarrassing yourself with your various identities. I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the role of self-criticism in your writing.

This reflects back on your comment about vulnerability. I’m compelled to take risks in my work, to write toward taboo, both content-wise and formally. This can create a lot of anxiety. To keep going I have to shut out my awareness of an audience and throw myself into my fictive world like some outsider artist perv. Think Henry Darger salivating over his nubile cut-outs. When I do that, subject matter becomes sculptural—these bits of material that I manipulate until everything makes sense in this alternate reality. Self-criticism comes in during gaps where I lose my focus, or sometimes when I’m up in front of a room giving a reading and I’m unexpectedly mortified, and there’s nothing else to do but to continue reading with an air of confidence while thinking, How could you write such sick fucking stuff?

Christopher Higgs is a visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Southeastern Louisiana University.

Read Everywhere, Part 6

Adam Leith Gollner, a contributor to the Daily, reads Issue 209 in Nanjing, China.

Celebrate summer—and get summer reading, all year round—with a joint subscription to The Paris Review and The London Review of Books.

The Paris Review brings you the best new fiction, poetry, and interviews; The London Review of Books publishes the best cultural essays and long-form journalism. Now, for a limited time, you can get them both for one low price, anywhere in the world.

Tell us where you’re reading either magazine—or both! Share photos from around the world with the hashtag #ReadEverywhere.

A Profound Experience of Art, and Other News

What the Mona Lisa sees all day—cue a quotation from the “Most Photographed Barn in America” section of White Noise. Photo: Susan Lesch

Museums have a real, if enviable, problem on their hands—they’re too popular. “Seeing masterpieces may be a soul-nourishing cultural rite of passage, but soaring attendance has turned many museums into crowded, sauna-like spaces, forcing institutions to debate how to balance accessibility with art preservation.”

A proposed virtual-reality edition of Ulysses sounds about as abstruse as the novel itself: “As a user of In Ulysses walks along a virtual Sandymount Strand, the book will be read to them—they will hear Stephen’s thoughts as they are written—but these thoughts will then be illustrated around the user in real-time using textual annotations, images, and links.”

Fewer people are giving books as gifts—the number of gift-book sales fell by nine million in a year. (If you’d like to reduce the deficit and you need an excuse to give, today is International Tiger Day.)

Trend alert: there’s never been a finer moment to be a deceased performer. “Two thousand fourteen is only half over, yet the year in culture has already been dominated by people who are dead … I mean people like Michael Jackson, who, five years in the grave, performed at the Billboard Music Awards in May. And Rick James, who’s been dead for a decade and who has a new memoir this year. And the great Philip Seymour Hoffman, who died in February and has a new movie out.”

From Disobedient Objects, a book about design’s effect on social change, a look at the storied history of defacing currency.

July 28, 2014

Working on My Novel

From Cory Arcangel’s Working on My Novel

“I wonder whether there will ever be enough tranquility under modern circumstances to allow our contemporary Wordsworth to recollect anything. I feel that art has something to do with the achievement of stillness in the midst of chaos. A stillness that characterizes prayer, too, and the eye of the storm. I think that art has something to do with an arrest of attention in the midst of distraction.” —Saul Bellow, the Art of Fiction No. 37, 1966

Cory Arcangel’s new book, Working on My Novel—based on the Twitter feed of the same name—is a compilation of tweets from people who are putatively at work on novels. No more, no less. On Twitter, this concept feels merely clever; printed and bound as a novel would be, though, it becomes a vexed look at novels’ position in the culture, and a sad monument to distraction. Or so it seems to me. Arcangel’s “elevator pitch” puts a brighter gloss on it:

Working on My Novel is about the act of creation and the gap between the different ways we express ourselves today. Exploring the extremes of making art, from satisfaction and even euphoria to those days or nights when nothing will come, it's the story of what it means to be a creative person, and why we keep on trying.

But the book piques my interest for the opposite reason: it’s the story of what it means to live in a cultural climate that stifles almost every creative impulse, and why it so often seems we should stop trying. Arcangel suggests there’s something inherently ennobling in trying to write, but his book is an aggregate of delusion, narcissism, procrastination, boredom, self-congratulation, confusion—every stumbling block, in other words, between here and art. Working captures the worrisome extent to which “creative writing” has been synonymized with therapy; nearly everyone quoted in it pursues novel-writing as a kind of exercise regimen. (“I love my mind,” writes one aspirant novelist, as if he’s just done fifty reps with it and is admiring it all engorged with blood.)

It’s also a comment on the peculiar primacy the novel continues to enjoy—not as an artistic mode but as a kind of elevated diary, a form of what we insidiously refer to as “self-expression,” as if anyone’s self is static enough to survive transmission to the page. Not for nothing do we have Working on My Novel instead of Working on My Screenplay or Working on My Scrimshaw, because the novel, with its rich intellectual-emotional tradition and its (very occasional) commercial viability, is still perceived as the ideal vehicle for saying something Ambitious. Even as fewer people read novels, we’re made to feel that writing one is a worthy, rigorous enterprise for serious thinking people, a means of proving that we have reservoirs of mindfulness and discipline deeper than our peers’. And so we try to write fiction, though certainly we don’t need to, and, as this book attests, we often don’t especially want to, even if we greet the task steeled by a perfect cup of coffee, a glass of red wine and a hot bath, or an Eminem song.

Plus, as Stephen Marche wrote in the Times this weekend, the reality is that very few of these writers, if any, will succeed. “The majority of books by successful writers are failures,” he writes. “The majority of writers are failures. And then there are the would-be writers, those who have failed to be writers in the first place.” But failure is seldom on the minds of these writers, except insofar as it stands, temporarily, between them and inevitable success. As of now, there are 675 of those would-be writers featured on the Twitter version of Working, and yet a rudimentary search shows that the word fail has been deployed exactly zero times. What prevails instead is a kind of Pollyannaish resilience, which certain sectors of the culture, as Marche explains, have misattributed to Samuel Beckett:

“Fail better,” Samuel Beckett commanded, a phrase that has been taken on by business executives as some kind of ersatz wisdom. They have missed the point completely. Beckett didn’t mean failure-on-the-way-to-delayed-success, which is what the FailCon crowd thinks he meant. To fail better, to fail gracefully and with composure, is so essential because there’s no such thing as success. It’s failure all the way down.

Indeed, if you hope to Fail Better—and if you hold up literature, as a writer or reader, as a form of bettering yourself, warts and all—you risk ensnaring yourself in a paradox that Jonathan Franzen wrote about in 1996, more than a decade before Twitter even existed:

You ask yourself, why am I bothering to write these books? ... I can’t stomach any kind of notion that serious fiction is good for us, because I don’t believe that everything that’s wrong with the world has a cure, and even if I did, what business would I, who feel like the sick one, have in offering it? It’s hard to consider literature a medicine, in any case, when reading it serves mainly to deepen your depressing estrangement from the mainstream; sooner or later the therapeutically minded reader will end up fingering reading itself as the sickness.

And so Working on My Novel is a brilliant litmus test—there are those who will read it as a paean to the fortitude of the creative spirit, and those who will read it as a confirmation of the novel’s increasing impotence. A form that should provide a “radical critique of the therapeutic society,” as Franzen writes, has instead been co-opted by that society. It’s failing better than the best Fail Better adherent could hope.

If You See Something

Photo: Jaroslav Thraumb

I was midway through a very different sort of post today when something unexpected happened: I got hit in the face on the subway.

It was an accident, but no less unpleasant for that. On the subway, you expect a certain amount of violence: in the course of a rush-hour commute you’re liable to be jostled, elbowed, crowded, and trod upon. If you are short, the incidence is even higher. But even by those standards this was unusual. Indeed, even by my own day’s standards—which seem to contain more petty indignities than a Benny Hill sketch—this was unusual.

Long story short: as we were both getting up to exit the 1 train, a man hefted his backpack and, in the process, backhanded me. Because his arm was propelled by the weight of his bag, and because I was in the midst of standing up, the blow was really hard. A gasp went up from everyone who had seen. He apologized, twice, but there really wasn’t anything he could do. And because there is nothing worse than refusing an apology for something done without intention, of course I accepted it, and tried to smile and pretend it was nothing.

It has been a while since I was punched in the subway. The last time was much worse. I got on the train with a heavy paper grocery bag in each hand. No sooner had I walked through the doors when a teenager, out of nowhere, punched me in the stomach. It wasn’t that hard, but the shock was enough that I dropped my bags, a plum rolled down the car, and—I would discover later—several eggs broke. His friends cackled with glee. No one did anything.

That wasn’t even the worst part. “Hey, sorry,” said the kid, after I had sat down. Then, “Give me a kiss.”

Now, I’m sitting here with a cold pack to my aching jaw—I have one of those cartoon-drunk ice bags. I think it is going to swell, but hopefully won’t excite too much comment. If I have to, I guess I could make some awful joke about Zsa-Zsa Gabor and New York, and try to be jaunty. But the truth is, I hate having to admit I’m a victim of the city, you know?

She Jazzes That Dazzling Verse

Courtesy of Yale University Press

Congratulations to Ansel Elkins, our poet-in-residence at the Standard, East Village, who’s featured in The New Yorker this week. (Complete with a terrific caricature by Tom Bachtell.) Elkins, who recently finished her residency, speaks to Andrew Marantz in the Talk of the Town section, discussing her time at the Standard, her unique position on the height spectrum (“between Lolita and Lil’ Kim”), and her persistent yearning for HoJo ice machines.

Elkins spent her days indoors, napping and listening to Hank Williams and revising her poems with colored pens … Most nights, she went out for three-dollar tacos on Second Avenue and walked back slowly, gazing up at the gargoyles on East Sixth Street. “This late-night walking is the one thing about the city that’s most saturated my work,” she said, mentioning a new poem, an ode to Mae West, that she began writing here. (“Singing in two languages— / English and body; / She jazzes that dazzling verse.”)

Read the whole piece here.

You’ve Been Fictionalized!

Or, Is this really what you think of me?

The shock of recognition.

Twenty-odd years ago, T. C. Boyle asked me about the artists’ colonies I’d been to—he was writing a novel. I described the lunches dropped off on the residents’ porches, the nightly readings and revels. When his book, East Is East, came out, I read a few chapters, then stopped, gut-socked and mortified. Yes, there, sprinkled in, was the material I’d given him, along with an added surprise—Wasn’t that me in those pages, and cast in a none-too-flattering light?

In real life, T. C. called me La Huneven, and here he called his heroine, Ruth Dershowitz, La Dershowitz. Ruth was a talentless writer who aspired to literary fiction while writing restaurant reviews and articles for Cosmo. Hey! I wrote restaurant reviews! And I’d once written an article for Cosmo! Was this, then, what Tom really thought of me? That I was a talentless airhead poseur trying to break into the hallowed world of literature?

This was my first experience of being fictionalized. I still recall the yellow-white flash of queasiness, the mortification: a sense of powerlessness and an utter lack of recourse.

* * *

So when my husband recently announced that he was uncomfortable about my putting him in a short story, I sympathized. Then I tried to explain.

“I didn’t put you in a short story!” I cried.

I swore to Jim that my young man owed far more to Owen Gereth in The Spoils of Poynton than to him. In fact, I’d used only a tiny nub of our shared life—a small family ring he’d been given for his bar mitzvah—but the use of it, Jim felt, implicated him.

“I’m not telling you not to write or publish the story,” Jim said. “I’m just telling you how I feel.”

I know that feeling. I wished there was something I could say so he wouldn’t take it so personally. But, wouldn’t you know, my next idea for a story came from something that happened on our honeymoon.

That wasn’t personal, either.

* * *

What can you do when you’ve been fictionalized?

Go fetal. Give the writer a good talking to. Write a letter of complaint. Write your own book, your way. Keep it to yourself and seethe. You can sue, but the bar for libel lawsuits involving fiction is very, very high. And so is the cost.

According to the libel lawyer Elizabeth McNamara, the fictionalized, like all litigants, sue for one of two reasons: because they feel wronged, or for money.

Your ex-girlfriend has put you in a story; you’re unmistakable—that’s your hair color, your tattoo, your speech impediment—only she’s made you a rapist.

Or your cheating, lying ex-boyfriend has written a best seller featuring you, your family, and all your best lines; he’s sold the screen rights, he’s raking it in. Why shouldn’t you have a share of the pot?

“Since time, immemorial writers have used real life to inspire them and build upon their experience,” says McNamara. “But invariably, characters diverge from reality.”

There’s the rub. And there goes your case, out the window.

* * *

Writers can take offense when someone asks what’s real or autobiographical in our work, because to us, that’s not what counts. The bits taken from life are tiny scales on the dragon’s tail—what about that whole beautiful writhing, fire-breathing dragon?

But one scale can assume enormous importance to the friend or family member who beholds him or herself in its shiny surface. Often—but not always—that’s a sick-making moment.

It isn’t as if a writer merely records life as it unfurls. Reality does not automatically transcribe as literature; real people are not shapely, compelling characters to be harvested. Charming facts and sharp observations rarely slide seamlessly into whatever narrative is at hand. To fictionalize material—any material, real or imaginary—is to subject it to the demands, the conventions, and rigors of the project at hand. A fictional narrative is constructed, shaped, and sized, its raw material muted, amplified, trimmed, and minced, recombined and recolored.

The writer Susan Taylor Chehak said that she was fictionalized once, “But by the time she got me to fit, I wasn’t me anymore.”

Not all are as cool-headed as Chehak. Some of the fictionalized share a wide streak of solipsism—for them, a few recognized facts can trigger a strong response. I have one friend who, years before I knew her, lived in Round Rock, Texas. She told me how, drunk in her youth, she’d once called some policemen “pin dicks” as they were driving her down to the station. I stole that line and gave it to a young man as he was being hauled to the police station in my first novel, Round Rock, which was named for a drunk farm near Piru, California, where round rocks occur naturally in the riverbed—it had nothing to do with Texas. My friend read two pages of this novel and phoned, furious. Not only had I named my novel after the place where she used to live, I’d put her words into my character’s mouth. “You stole my life!” she said.

I’m sure, for a few moments, she felt burgled and betrayed. I’d felt that way, too, when reading about La Dershowitz in East Is East. The first wash of it is the worst.

So why are we so shocked, startled, and gut-socked to glimpse ourselves on the page?

Not long ago, I opened my MacBook Air to see a strange older woman frowning at me. It took a moment to realize I’d accidentally opened Photo Gallery and—horrors upon horrors—that big-nosed grouch was me.

An unexpected reflection of self rarely provokes joy.

* * *

Because the shock of recognition is so acute, the fictionalized often fail to grasp how impersonally their “personal” material is used—or how minor a role “their” material plays.

As a novelist, I tend to know significantly more about my characters than I do about my friends. (For example, I do not necessarily know my friends’ preferred brand of shampoo, or their dental histories, or how they behave in bed.) Even when I’ve borrowed a character from life, I have to fill in a lot of blanks, not to mention make them do things they’ve never done in life. Often, it’s this auxiliary material that the fictionalized find especially painful, for they see in it a kind of subconscious, inadvertent truth telling.

It is not uncommon for the fictionalized to assume that the writer has revealed the real, possibly hidden way they feel and think about a person. Another correspondent writes of seeing herself in a friend’s work: “It was deeply unpleasant, unfair, desperately mean but—let’s see, the good side? It was very, very revealing of certain of the author’s subterranean feelings for me—ones I’d long suspected and which she’d always denied.”

The experience of being fictionalized can be like overhearing people talk about you when they don’t know you’re there. The temptation is to give what you overhear great credence, as if people would only say what they really think about you behind your back. But behind your back is also where people are most free to vent, to be peevish, unfair, sniping, and slanted; behind your back is where they are most apt to try out imprecations and outlandish opinions and, in general, to be far less generous or compassionate or accurate than they probably are.

The laws of literature, like the laws of gossip, usually demand exaggeration, decontextualization, a heightened or minimalized reality, and a lot more shape and order and impact than everyday life. “You’ve been fictionalized” actually means, “You’ve been exaggerated!” (Or downplayed!) You’ve been snipped and shaped and built on, face-lifted, aged and/or repainted for maximum artistic impact.

It would be naive to claim there aren’t writers who write from a deep sense of rage, a yearning for justice, a need to get something off their chests. Certainly, some writers do take personal revenge in their work, and yes, some do spill all kinds of unconscious matter onto the page.

I knew a writer who kept a list of enemies to be skewered down the line—editors who’d rejected her work, critics who’d been less than kind, colleagues and others who’d slighted her. She did her skewering subtly, mostly in little in-jokes that only she and a few intimates would enjoy. I’m not sure her victims recognized themselves (no fool, she), but revenge is a mighty energy. Why shouldn’t a writer harness such potent wrath from time to time?

But I would argue that most writers use material in the way a coyote eats a mouse—impersonally, pragmatically, with neither pity nor loathing, to fulfill a need.

When Tom Boyle caught wind of my dismay those many years ago, he in turn was mortified, and wrote a note saying he’d intended nothing personal at all. I should have known that, too, because all material fed into T. C.’s brain had a good chance of coming out satirized, outsized, and hilarious.

Then again, I got off easy. A mutual friend recently wrote, “I learned about my wife’s affair from T. C.’s book.” (Which book, he didn’t say.)

* * *

Of course, not everyone objects to being in a novel or story, even if the portrayal is unflattering. I met a man once who, within minutes of our introduction, informed me that he was the prototype for Chip in The Corrections—a claim not everyone would be quick to make. And my neighbor happily tells people that she’s a character in my latest novel, Off Course. Actually, she’s part of a composite character, and she never said or did ninety percent of what that character says and does—although she did, like the character in my book, make a great beef stew and manage an apartment complex thirty years ago.

Boyfriends and girlfriends, says McNamara, are among the most fictionalized, and thus the most outraged. But two of my former boyfriends were flattered to be represented in my fiction. “It’s an honor to contribute to art,” said one. “I liked that character. He was cool,” said the other. A third boyfriend was so secretive and private, he suffered a kind of preemptive anxiety around me. Whenever I asked even a faintly probing question he’d say, “What, are you writing a book?”

Eventually, yes, I wrote that book.

And then there’s the fictionalizing of a person you don’t even know. In my first novel, the central character is a man named Red Ray. I made him up from whole cloth, or thought I had. At a reading, a stranger came up and told me that he knew Red, who was now living near San Diego.

* * *

If you’ve been fictionalized, it’s unlikely that many others will notice you in the story. If they do, it’s unlikely much will be made of your cameo, or even your starring role. Frankly, nobody cares as much as you do. Not one person among many mutual friends has ever suggested that La Dershowitz is a facsimile of me. In fact, I recently went back to East Is East to find the passages that had caused such uneasiness twenty years ago. Yes, there, in a subplot, was La Dershowitz and, amid myriad other details, was one glancing reference to restaurant reviews and Cosmo. So much else was going on in the book—all of which I’d forgotten—the objectionable details were very far apart. In this reading, it wasn’t even clear if La Dershowitz was untalented. There was certainly nothing to be upset about.

And yet, once I saw my own worst fears knit into those sentences.

On seeing oneself in fiction, it might help, then, to attempt a larger view. Take a deep breath. Consider the passage or character your contribution, however inadvertent, to art. Try not to take it so personally. Don’t read too much into it. Cultivate lightness.

Victoria Patterson, in her debut story collection, Drift, drew heavily from growing up in a wealthy seaside community and her parents’ divorce. “It occurs to me now how very autobiographical the book is,” Patterson writes, “and how painful it must have been for my parents to read it, and how lovely that they still speak to me!” In the book, as in life, the heroine’s mother inappropriately confides in her, divulging that the girl’s father had been “a marginal lover.”

When the collection came out, Patterson’s father phoned her. “I’m happy to report some improvement,” he said. “I can now say I’m a solidly average lover.”

Michelle Huneven is the author of the novels Off Course; Blame, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; Jamesland; and Round Rock. She lives in Altadena, California, with her husband, Jim Potter.

When Shades Meant Shady, and Other News

Sunglasses: take ’em off! Photo: Zarateman, via Wikimedia Commons

“It’s not too much of an exaggeration to call autocorrect the overlooked underwriter of our era of mobile prolixity. Without it, we wouldn’t be able to compose windy love letters from stadium bleachers, write novels on subway commutes, or dash off breakup texts while in line at the post office.” The wondrous history of autocorrect, including a brief meditation on the nature of profanity. (Because autocorrect “couldn’t very well go around recommending the correct spelling of mothrefukcer.”)

“Three hundred thousand books are published in the United States every year. A few hundred, at most, could be called financial or creative successes. The majority of books by successful writers are failures. The majority of writers are failures. And then there are the would-be writers, those who have failed to be writers in the first place, a category which, if you believe what people tell you at parties, constitutes the bulk of the species.”

On the distinct merits of Bolaño’s Distant Star: “At some point in 1995, Bolaño seems to have discovered that he could expand a published text without diluting its effect or getting bogged down in circumstantial details, and that he could bring back characters and give them fuller lives without being strictly constrained by what he had already written about them.”

After twenty-seven years, the Rodeo Bar, “New York’s longest-running honky-tonk,” has closed.

“I’m not happy about people wearing sunglasses at all. Proper upstanding citizens never used to. They preferred to leave that sort of thing to dodgy characters from the underworld.”

July 25, 2014

What We’re Loving: Algiers, Aliens, Adulthood

George Saunders talks to an alien. Detail from an illustration by Thomas Allen, in O, the Oprah Magazine.

I went on vacation planning to read Tristram Shandy, at last. Instead I read Frank Kermode on “Modernisms,” most of The Rise of the Novel (including the chapter on Tristram Shandy), and half the Selected Poems of Howard Moss. Total reading time: not much. But it was choice. Then I got home and found The New Yorker in my mailbox. Greg Jackson’s “Wagner in the Desert” is the best fiction debut they’ve published in years. The story belongs to an ancient genre: young, rich people hole up in a country house to avoid the plague. In this case, the country house is a rental in Palm Springs, the plague is adulthood, and the hosts are a Hollywood couple about to start fertility treatments, hoping to get their ya-yas out in a mindful, caring way. Jackson knows his antecedents. He has metabolized Ben Lerner and David Foster Wallace. He can throw in a blank verse, like Melville, to heighten a scene. He even steals, without attribution, from Kenny Rogers. I read “Wagner in the Desert” my first night back, fell asleep, and dreamed I was in the story (and also back in elementary school, getting a lesson in the story) then woke up and read it again, with no diminution of enjoyment. —Lorin Stein

I’ve been reading Adam Shatz’s very smart account of how reporting on the Middle East cured him of political romanticism. I suspect he’s not alone in this experience: “When I finally began to spend time in the place about which I had pontificated for so long, I discovered that I was much more interested in what the people I met had to say than in my own views.” My favorite parts are Shatz’s trips to Algiers—“a city I knew mostly from Gillo Pontecorvo’s film”—and his interview with Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. It’s a sobering essay, and a timely one for this low point (after a very high one) in the history of the region. —Robyn Creswell

In this month’s O, The Oprah Magazine, George Saunders explains to a space alien what it means to be human. His explanation takes the form of a series of short-story recommendations, of course. Drawing on diverse selections from Chekhov to Hemingway to Lahiri, he covers the basics of love, loneliness, greed, kindness, death, and empathy. The essay’s a gem, a genuine love letter to reading as a noble pursuit. Saunders says it best: “Short stories are the deep, encoded crystallizations of all human knowledge. They are rarefied, dense meaning machines, shedding light on the most pressing of life’s dilemmas. By reading a thoughtfully selected set of them, our alien could, in a few hours, learn everything he needs to know about the way we live. Except how it feels to lose one’s car in a parking garage and walk around for like three hours, trying to look as if you know where you’re going, so the people driving by—who have easily found their cars, having written the location on their wrists or something—don’t think badly of you. I don’t think there’s a short story about that yet.” —Chantal McStay

Another thing I did on vacation was see The Shining for the first time in a couple of decades. This, unfortunately, was the director’s cut, in which Jack Nicholson has several long, boring conversations with ghosts. But even the scary parts weren’t scary anymore. To hear J. D. Daniels tell it in the new issue of Flaunt, I’d rather have seen the documentary Room 237—at least, if I got to see it with J. D. Daniels: “Room 237 is about unhinged Stanley Kubrick fanatics … Each of them thinks The Shining is a coded message. One participant believes The Shining is Kubrick’s confession that he helped NASA fake the Apollo 11 moon landing. Have you seen The Shining? It’s about an axe murderer. It’s about 145 minutes long.” —L.S.

The Lebanese poet Kahlil Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, just behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu—but his writing is generally neglected. Gibran’s most renowned work is The Prophet, a collection of twenty-six prose poems that delve into philosophy, spirituality, and religion. The Prophet has sold widely since its publication in 1923, but its inspirational voice has precluded it from critical acclaim. Some find Gibran’s poetry preachy and moralizing, but I find it plenty enlightening—it’s hard to object to the melodic, cosmic of mysticism of a line like “That which sings and contemplates in you is still dwelling within the bounds of that first moment which scattered the stars into space.” —Yasmin Roshanian

I’ve been reading Iris Murdoch’s essays “The Sublime and the Good” and “The Sovereignty of the Good,” in which she contends, as so many do, that man is an essentially selfish creature; his narcissism distorts and thwarts reality. Murdoch’s elegantly simple prescription is to get the self to stop thinking about the self simply by looking around: at paintings, at ladybugs that land on us, et cetera. This type of basic observational experience, she maintains, is important for our moral lives—through it we cultivate a sensitivity to the particularities of the other. And once we have that, Murdoch says, we might become better people. —Parker Henry

The Vale of Soul-Making

How Keats coped with fever.

Tuberculosis seemed to pursue Keats his whole life.

In 1821, three months after he learned of Keats’s death, Percy Shelley wrote Adonaïs: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, in which he described the poet as a delicate, fragile young flower of a man:

Oh gentle child, beautiful as thou wert,

Why didst thou leave the trodden paths of men

Too soon, and with weak hands though mighty heart

Dare the unpastured dragon in his den?

That dragon was a cruel critic who had mocked Keats’s literary ambitions—John Gibson Lockhart, who, writing under the pseudonym Z, had scolded Keats as if he were a child, insisting in a review of Endymion that “it is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop, Mr John, back to the ‘plasters, pills, and ointment boxes.’ ” Lockhart had classed Keats among the Cockney School of politics, versification, and morality, known—at least by readers of Blackwood’s Magazine—for its “exquisitely bad taste” and “vulgar modes of thinking.” In Shelley’s formulation, it was this bad review that sent Keats to an early grave, and gazing back through history, one begins to accept this two-part narrative of Keats’s legacy. The fallen poet had lived a life of abstractions—he was not only an aesthete, but the aesthete—and he had been, as Byron quipped, “snuffed out by an article,” too beautiful and frail for this harsh world.

But Keats was immersed in the realities of life; his poetry and letters reveal an allegiance to radical politics as well as a concern with economic and scientific issues. Far from childlike and apolitical, he’s now thought of as having been “dangerous … a poet who embodied and gave voice to the anxieties and insecurities of his times … a poet whom the establishment would be obliged to silence,” as the scholar Nicholas Roe puts it. We often overlook, for instance, that Keats spent six years studying medicine, successfully earning a license to practice in London from the Society of Apothecaries—hence Lockhart’s insult about the “plasters, pills, and ointment boxes.” To think that he was “snuffed out by an article” trivializes the intense pain he experienced as his lungs were slowly consumed by tuberculosis, robbing him of his work, his love, and his life at the age of twenty-five.

The myth of the frail genius is attractive, even to contemporary readers, because of its quintessential Romanticism. But the truth is that Keats’s writings—especially when they seem fanciful or escapist—are grounded in real-world concerns. And nowhere is this more evident than in the letters and poems of his that deal with feverish suffering.

During the early nineteenth century, London had fallen into the grip of fever mania. The city was working to combat a host of diseases associated with the colonies: yellow fever, typhus, influenza, smallpox, child-bed fevers, agues, and St. Anthony’s fire, among many others. With almost a million people living in the city in the early 1800s, including more than ten thousand prostitutes, disease spread quickly, inducing public panic. Between 1816 and 1817, the number of admissions to the Fever Hospital spiked from 124 to 781, and the fever epidemic remained a major news story for the duration of Keats’s life. Whereas some historians have viewed the fever as a foreign invader, striking from the colonies upon the homeland, Keats would have recognized it as a recurrent, intimate presence that followed him throughout his life.

The patients whom he attended at Guy’s Hospital haunted him, as did the memory of his mother’s fatal consumptive fever, which he would relive as he nursed his brother, Tom, throughout 1818. Because of his family’s history of illness, his own medical training, and the epidemic of fever that spread throughout London, Keats was intimately familiar with feverish suffering; he used his writing to make sense of a pain for which there was no reasonable explanation. Two letters—one written before Tom’s death and one after—outline Keats’s philosophy of suffering as a creative force.

* * *

On May 3, 1818, Keats wrote a letter to his friend, John Hamilton Reynolds, comparing a human lifespan to “a large Mansion of Many Apartments.” He imagined two rooms in a mansion through which one must pass before confronting a vast number of potential third rooms. For an unspecified length of time, one remains unthinkingly in the first apartment, in spite of the fact that the doors leading to the second are wide open. Eventually, the impetus to think moves one from the first chamber into this second, called the “Chamber of Maiden-Thought,” which is full of intoxicating delights and thus initially very pleasing. But time spent within it leads to a “sharpening [of] one’s vision into the heart and nature of Man … convincing ones nerves that the World is full of Misery and Heartbreak, Pain, Sickness and oppression.”

One becomes aware of one’s own fever and the suffering that afflicts humanity—which were present all the while, even amid the delights. Keats thought he’d only made it to the end of this second room. He saw nothing but darkness and mist in the hallway beyond it. He told Reynolds that he wished to explore the dark passages to seek out some form of salvation by way of his poetry, though he offered no compelling evidence that any of the unexplored rooms might contain something redemptive, or even pleasant.

Surrounding this philosophical discussion are the details of Tom’s illness. The letter begins with what appears to be good news: “After a Night without a Wink of sleep, and overburdened with fever, [Tom] has got up after a refreshing day sleep and is better than he has been for a long time,” and ends with restrained melancholy: “Tom has spit a leetle [for little] blood this afternoon, and that is rather a damper.” But insofar as Keats was hoping to justify the purpose of suffering to himself, both of these statements are heartbreaking. Because of his extensive experience with ill patients, Keats surely knew that his brother’s condition was grim, even in May 1818. His reactions hint at a kind of denial—an insistence that there be an identifiable purpose to justify the trauma he continued to witness and endure. And once he has convinced himself that there is a purpose to suffering, it is only another small leap to start thinking of the fever as something constructive. Indeed, as odd as it may seem, it was his brother’s grim condition that prompted, even forced, Keats to expand his philosophy of suffering to embrace fever as beneficial. The search for the third room, undertaken in the midst of suffering, had to lead to the creation of something meaningful and redemptive, as Keats would try to convince himself after Tom’s death in December 1818.

Joseph Severn’s drawing of Keats on his deathbed.

* * *

In the spring of 1819, Keats was at the height of his genius; within the next few months he would write his finest poems. In a letter from April 21, 1819 to his other brother, George, who had emigrated to America, Keats revisited his philosophy, unveiling the “system of Spirit-creation” that he’d been designing and testing for more than a year: the world as the “vale of Soul-making.”

Keats argued that any attempts to improve one’s life still end in death—a fate that he acknowledged as unbearable without some notion of redemption. And yet he rejected the idea of the afterlife or religious salvation—those, in his view, devalue the act of suffering, because they serve no creative purpose and teach nothing to the human individual.

Instead, he referred to the raw material of a soul as an “intelligence.” All humans have (or are) an intelligence, but they’re not considered souls until they develop an individual identity. Soul creation takes place over the span of many years and requires two components—the human heart and the world of feverish suffering—comprising a process that Keats likens to an education:

I will call the world a School instituted for the purpose of teaching little children to read—I will call the human heart the horn Book used in that School—and I will call the Child able to read, the Soul made from that school and its hornbook. Do you not see how necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a soul? A Place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways!

The “vale of Soul-making” celebrated the fever that had followed him through his life. And yet what Keats could not, or refused to, see is that the irrationality he perceived in religious salvation is present in his own system, too. There’s no ultimate purpose to the suffering that he, his family, and his patients have had to endure; it’s not as if the fever of tuberculosis consciously, benevolently struck Keats’s mother and brother to help them shape their souls. But Keats went to great lengths to convince himself of just that.

While the fever had surrounded him for most of his life, it consumed Keats during the months following Tom’s death, insisting that he find some way to rationalize its irrational effects. In fact, compared with other medical terms, Keats uses the word fever sparingly in his poems: blood is explicitly referenced forty-seven times (and implicitly in at least a dozen other instances), and there are 157 variations of heart, but only twenty-three instances of fever appear across the body of Keats’s poetry.

This shouldn’t mislead us into thinking that it’s a less potent image for him. His prudent use of the term demonstrates its importance—it’s loaded with personal significance. All but five of these uses of “fever” occur after Tom became ill, the most poignant of which comes in “Ode to a Nightingale,” written only a few days after the “vale of Soul-making” letter.

The feverish heart overwhelms the speaker of the “Ode to a Nightingale,” who suffers a heartache as he listens to the nightingale’s song, hoping to mirror the bird’s ability to transcend real-world circumstances. The speaker describes the world as

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs.

Keats must have had Tom’s death in mind when he composed these lines; every phrase is loaded with the common suffering of humanity from which the nightingale’s song seems to escape.

Less than two years later, Keats died of tuberculosis in Italy, where he’d traveled in the hope of recovering, accompanied by the artist Joseph Severn. Even as he grew shorter and shorter of breath in early 1821, Keats repeatedly rejected his dear friend Severn’s belief in the afterlife, suggesting that he was committed to his philosophy of Soul-making until the end. Severn wrote in mid-January: “this noble fellow lying on the bed—is dying in horror—no kind hope smoothing down his suffering—no philosophy—no religion to support him.”

When the end came, it was the fever, and not an article with obvious political motivations, that killed Keats. The pleasures of his life—beauty, love, poetry—had always been bundled up with suffering and death, and we may empathize with him in his desire to articulate a purpose to it all. He was not too frail for the world: his devotion to making the most of his mortality drove his creative process. He was a man who had a deep need to create meaning where there was none.

Jeffrey C. Johnson is a writer living in California. His writing can be found on his website, and he is on Twitter.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers