The Paris Review's Blog, page 678

July 31, 2014

How to Win Friends and Influence People

Daniel Defoe, beloved in the pillory. Line engraving by James Charles Armytage, 1862

Before he wrote Robinson Crusoe or Moll Flanders—before he wrote any novels at all, actually—Daniel Defoe was a pamphleteer, fomenting controversy in the London of the early eighteenth century. On July 31, 1703, he landed himself in the pillory for seditious libel; he’d written an anonymous satire mocking the hostility toward Dissenters, suggesting that the whole lot of them should be killed. It didn’t take long for authorities to pin him as the author. Then they did what authorities do: fined him to the point of bankruptcy, threw him in prison, and subjected him to ritualized public humiliation.

Before his stint in the stocks began, Defoe managed to write and disseminate a poem, “Hymn to the Pillory.” Legend has it, however dubiously, that the public was so enamored of his verse that they came to greet him at the pillory with flowers, toasting his health instead of hurling stones at him.

Lesson learned: in the court of public opinion, nothing carries more weight than a well-timed poem. Bear this in mind next time you’re stoking the flames of religious unrest in your community.

On the Slaughter

A political poem’s ironic new life.

Bialik at around age thirty.

ON THE SLAUGHTER

Heaven—have mercy.

If you hold a God

(to whom there’s a path

that I haven’t found), pray for me.

My heart has died.

There is no prayer on my lips.

My hope and strength are gone.

How long? How much longer?

Executioner, here’s my neck:

Slaughter! You’ve got the ax and the arm.

The world to me is a butcher-block—

we, whose numbers are small

it’s open season on our blood:

Crack a skull—let the blood

of infant and elder spurt on your chest,

and let it remain there forever, and ever.

If there’s justice—let it come now!

But if it should come after I’ve been

blotted out beneath the sky,

let its throne be cast down.

Let the heavens rot in evil everlasting,

and you, with your cruelty,

go in your iniquity

and live and bathe in your blood.

And cursed be he who cries out: Revenge!

Vengeance like this, for the blood of a child,

Satan has yet to devise.

Let the blood fill the abyss!

Let it pierce the blackest depths

and devour the darkness

and eat away and reach

the rotting foundations of the earth.

Political poems lead strange lives—they often wither on the vines of the events they’re tied to. Old news gives way to new, and the whole undertaking starts to seem, well, an expense of spirit in a waste of shame. For many and maybe most American readers, “poetry and politics just don’t mix.”

But sometimes they do. Quite violently.

On June 12, three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped while hitchhiking home together from their West Bank yeshivas. They were murdered—most likely within hours of being taken—and, eighteen days later, after an extensive search, their bodies were discovered under some rocks in a field near Hebron. Israel mourned, and raged. Emerging from a cabinet meeting convened just after the corpses were found, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu expressed his condolences to the families and quoted the great modernist Hebrew poet Hayim Nahman Bialik: “Vengeance … for the blood of a small child, / Satan has not yet created.” He went on in his own words: “Hamas is responsible—and Hamas will pay.” For good measure, the Prime Minister’s office tweeted the lines as well.

As anyone who hasn’t lived atop a column in the Congo for the past seven weeks knows, a series of violent, retaliatory acts followed. Israel carried out mass arrests on the West Bank, killing six in the process; a Palestinian teenager was beaten and burned alive by a group of Jews; throngs of Palestinians destroyed tracks and stations on the Jerusalem light-rail line; Jewish gangs shouting “Death to the Arabs!” rampaged through Jerusalem in search of victims—and found them; some thirty-five thousand Facebook users “liked” a page called “The People of Israel Demand Revenge”; Hamas fired rockets by the dozen into Israel from Gaza; Hamas officials warned that “the gates of hell” would open if Israel attacked in retaliation for the killings or the shelling.

On the night of July 7, the gates opened, even as they were being closed, when the Israel Defense Forces launched what it calls for export Operation Protective Edge. (A more literal translation of the operation’s catchy Hebrew name would be Firm Cliff—with “cliff,” according to the Hebrew equivalent of the OED, evoking in its primary definition the high place in the wilderness off of which a scapegoat is cast each year on the Day of Atonement. Words, as we know, have powers often lost on those who speak them.) After ten days of intensive air strikes, IDF ground troops entered the fray, ostensibly to destroy the tunnels where weapons were being stored and from which attacks were dispatched. But also in Israel’s sights, it seems, was the newly formed Fatah-Hamas unity government and a real-world partner for peace.

As I write on Wednesday evening, July 30, the “operation,” which is looking more and more like a war, has claimed the lives of more than 1,300 Palestinians—most of them civilians, and many of them children—and fifty-nine Israelis, three of whom were civilians. Some 6,500 people have been wounded on the Palestinian side, and several hundred on the Israeli, counting both combatants and civilians. Large swaths of Gaza lie in ruins. The Israeli air force has destroyed Gaza’s only power plant, knocking out the strip’s electricity and sewage. Food is spoiling; water is scarce; disease is rampant.

Several days before Israel deployed its Protective Edge, a New York Times article quoted Netanyahu quoting Bialik; a few days later, the paper’s editorial deplored the metastasizing racist rhetoric. “Even Mr. Netanyahu,” the paper wrote, “referenced an Israeli poem that reads: ‘Vengeance for the blood of a small child … ’ ” Then it carefully weighted the paragraph for the usual pantomime of equal time, noting that Israelis have long had to live with Hamas’s violent ways and put up with hateful speech from Palestinians.

Never mind that the poem intoned by Mr. Netanyahu wasn’t Israeli: it was written long before the state was founded and very far from it. “On the Slaughter” was the thirty-year-old Odessan Hayim Nahman Bialik’s immediate response to the April 1903 pogroms in the Bessarabian town of Kishinev, where some forty-nine Jews were slashed, hacked, and cudgeled to death, or drowned in outhouse feces, and hundreds were wounded over the course of several days. Women and girls were raped repeatedly. The Jewish part of town was decimated. Netanyahu quoted just two lines, carefully avoiding the one preceding them: “Cursed be he who cries out: Revenge!”

And he certainly didn’t mention the circumstances of the poem, in which a powerless Jewish community was massacred by Russian townsmen—a mad medley of ax-, pick-, knife-, and club-wielding seminarians, peasants, students, workers, thugs, and more—while the world went about its business. With the eyes of Israel upon him, the prime minister simply used (or abused) the implied comparison to fan fires that were already flaring.

* * *

Bialik was hardly a pacifist. “On the Slaughter”—the title alludes with the darkest irony to the blessing recited by Jewish ritual slaughterers before “humanely” slitting an animal’s throat, and also to Jewish martyrs in the middle ages who killed themselves before their Christian tormentors could—was, and is, a cry of despair, of hope exploding, of impotent anger in the face of base hatred and brutal injustice. And the poet would go on elsewhere to rail against Jewish passivity and to call for Jews to defend themselves, lambasting writers who retreated into aesthetics and refused to let politics sully their work.

But political poems lead strange lives, and if one didn’t know the circumstances of the composition of “On the Slaughter,” or who its author was; if one came across the poem in Arabic—in, say, its potent 1966 translation by the first star of Palestinian resistance poetry, Rashid Hussein, or (let us imagine) a YouTube reading of Hussein’s translation by a thirty-year-old poet in what’s left of the Gazan neighborhood of Sheja’iyeh—one could easily think it had been written by a Palestinian. Yesterday.

Who is being slaughtered now? Who cries out for an absent justice? Who for revenge? Where is cruelty? And where iniquity?

Political poems, good political poems, outlive the events that shape them. They turn in the wind and up on our screens. In the oddest of ways, they call from our bookshelves or a newspaper’s page. They lead strange lives. Sitting in my Jerusalem study, translating Bialik’s poem and thinking of the carnage and chaos in Gaza, as the Hebrew radio blares from the kitchen—with its mix of news, rocket alerts, and syrupy pop songs (the inevitable sound track to war in this country: “I Don’t Have Another Land,” and “Me and You, We’ll Change the World”)—I find myself feeling it’s my heart that’s dying. My hope and strength that are failing. That I’m the one asking, with that young could-be poet from Gaza, and just about all of the rest of the world: How much longer?

MacArthur fellow Peter Cole’s most recent book of poems is The Invention of Influence (2014).

Ovid (or You) in Ossining, and Other News

Photo: Jason O'Neal, via Newsweek

Want to buy John Cheever’s old house in Ossining? Have at it. (A mailbox bearing the Cheever name is still there.)

On the late Thomas Berger’s Arthur Rex, a 1978 retelling of Arthurian legend: “Berger adopts the distinct voice of the medieval-epic narrator, slipping easily into the rhythm and pattern of courtly speech, with its ‘And’s and ‘Now’s and ‘Whilst’s, its frequent and self-serious references to the glory of God and the sin of doubt. He uses the old style of speech to tell what has always been a surprisingly modern story: that of a kingdom in which every socioeconomic problem is brilliantly resolved and its people turn to a pure and destructive religious idealism.”

The actress Lisa Dwan is taking her production of three one-woman Beckett plays—Not I, Rockaby, and Footfalls—on a world tour.

Advice for reading blurbs: Don’t. “Cover blurbs aren’t reviews. They’re advertisements. No space for balanced, nuanced positivity. Nothing can be interesting; it must be fascinating. Good isn’t good enough; it must be great.”

“Rock stars are not gods but rather human beings whose emotions happen to resonate with millions—emotions that are inspired by other human beings, some of whom have written memoirs. These books are often disregarded as attempts to cash in, but while the books are sometimes bitter, they’re rarely cynical. Taken together, they comprise a shadow history of classic rock, an account from within the aura and from the margins of the rock star’s hero journey.”

July 30, 2014

Still Slacking After All These Years

Everyone’s talking about Richard Linklater’s Boyhood at the moment—as well they should; it’s a remarkable film—but in honor of the director’s birthday, you should revisit his first feature, Slacker, which is freely available on YouTube.

The Criterion Collection’s site has a few insightful essays on Slacker, too. There’s “Freedom’s Just Another Word for Nothing Left to Do,” by Chris Walters, which was written in and about 1990, but feels right at home in 2014:

The all-but-total decay of public life has atomized others into subcultures of which they are the only member, free radicals randomly seeking an absent center as the clock beats out its senseless song.

The movie buries its treasure here, in the crevasses of its drollery and craziness. Nothing in the current climate is more permissible than mocking or reducing such people; Slacker celebrates their futility as a sign of endurance and mourns the passing of time by marking it with emblems of affection and empathy, the only prizes worth having.

Or Ron Rosenbaum’s “Slacker’s Oblique Strategy,” originally published in the New York Observer, which makes a seemingly outlandish but ultimately shrewd claim:

Slacker is at heart a very Russian film. Not just in its obvious kinship to Oblomov, Ivan Goncharov’s great nineteenth-century Russian novel, the classic celebration of the luxuriant pleasures of lethargy and the sensual delights of the contemplative life. There’s another Russian link, to Turgenev and his novels of the “superfluous man.” (And, to make a cross-cultural comparison, there’s a link as well to the seventeenth-century British pastoral “poetry of retirement” tradition, whose varieties are best limned in a volume with the lovely title The Garlands of Repose by the scholar Michael O’Loughlin.)

But on a deeper level, the true Russian kinship is less with Goncharov or Turgenev than with Dostoyevsky, to a novel like The Brothers Karamazov: the kind of novel that is unashamed in its preoccupation, its obsession, with ultimate philosophical and metaphysical questions.

And remember, in closing, the wise slogan proffered by one of Slacker’s many hitchhikers: “Every single commodity you produce is a piece of your own death!”

Emily Brontë’s Boring Birthday

Emily’s portrait by her brother, Branwell.

It’s Emily Brontë’s birthday, and wouldn’t you know it—of her famously scarce surviving documents, several are letters written on and about the anniversary of her birth. Imagine! Rare glimpses into the thoughts of the most inscrutable Brontë sister! As Robert Morss Lovett wrote in The New Republic in 1928, Emily “was the household drudge … the ways by which her spirit grew into greatness and by what experience it was nourished, remain a mystery.”

And her biography at the Poetry Foundation deepens the mystique:

She is alternately the isolated artist striding the Yorkshire moors, the painfully shy girl-woman unable to leave the confines of her home, the heterodox creator capable of conceiving the amoral Heathcliff, the brusque intellect unwilling to deal with normal society, and the ethereal soul too fragile to confront the temporal world.

Let us turn, then, with not undue trepidation, to the letters themselves, precious reflections from one of English fiction’s brightest luminaries. A note from July 30, 1845 begins:

My birthday–showery–breezy–cool–I am twenty seven years old today–this morning Anne and I opened the papers we wrote 4 years since on my twenty third birthday–this paper we intend, if all be well, to open on my 30th three years hence in 1848–since the 1841 paper, the following events have taken place

Our school-scheme has been abandoned and instead Charlotte and I went to Brussels on the 8th of Febrary 1842 Branwell left his place at Luddenden Foot C and I returned from Brussels November 8th 1842 in consequence of Aunt's death–Branwell went to Thorp Green as a tutor where Anne still continued–January 1843 Charlotte returned to Brussels the same month and after staying a year came back again on new years day 1844 Anne left her situation at Thorp Green of her own accord–June 1845 Branwell left–July 1845 …

Oh. Hmm.

Well, she probably just needed a little time to clear her throat … Maybe if we just skip ahead a little bit …

Tabby who was gone in our last paper is come back and has lived with us–two years and a half and is in good health–Martha who also departed is here too. We have got Flossey, got and lost Tiger–lost the Hawk. Hero which with the geese was given away and is doubtless dead for when I came back from Brussels I enquired on all hands and could hear nothing of him–Tiger died early last year–Keeper and Flossey are well also the canary acquired 4 years since

We are now all at home and likely to be there some time–Branwell went to Liverpool on ‘Tuesday' to stay a week. Tabby has just been teasing me to turn as formerly to-‘pilloputate’. Anne and I should have picked the black currants if it had been fine and sunshiny. I must hurry off now to my taming and ironing I have plenty of work on hands and writing and am altogether full of buisness with best wishes for the whole House till 1848 July 3oth and as much longer as may be I conclude

I’m afraid it’s true. Emily Brontë’s birthday letters are totally dull. See for yourself.

Arguably their blandness strengthens—or complicates, at least—the aura surrounding her work. How did such a prosaic diarist produce Wuthering Heights not even two years later? The letters seem to support the popular notion that Emily was some kind of savant, an uneducated, frivolous young woman who wrote, as a fluke, one incredible book. But, as the Poetry Foundation notes, she was also the author of twenty-one poems, all significantly more mature than the birthday letters, and she was working toward a translation of the Aeneid, fragments of which have survived.

None of it adds up to a cohesive portrait. And as trifling as it is, that 1845 letter is shot through with dramatic irony; Emily writes that she and her sister intend, “if all be well,” to revisit the letter “on my 30th three years hence in 1848.” All was not well. That thirtieth birthday was her last—she died of tuberculosis in December 1848. Two years later, her sister, Charlotte—her first “mythographer,” as Lucasta Miller puts it—wrote in the introduction to Wuthering Heights:

My sister’s disposition was not naturally gregarious; circumstances favoured and fostered her tendency to seclusion; except to go to church or take a walk on the hills, she rarely crossed the threshold of home. Though her feeling for the people round was benevolent, intercourse with them she never sought; nor, with very few exceptions, ever experienced. And yet she know them: knew their ways, their language, their family histories; she could hear of them with interest, and talk of them with detail, minute, graphic, and accurate; but WITH them, she rarely exchanged a word.

Repent at Leisure

Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, Une noce chez le photographe, 1879

My father is a great TV watcher, and he keeps me abreast of the state of American television. Recently, he urged me to watch the U.S. reboot of the British reality show Married at First Sight, which, as the title suggests, introduces two willing strangers at the altar and marries them, albeit with the input of shrinks, matchmakers, sexperts, and various other professionals.

“It’s fascinating,” my dad assured me.

“I don’t want to watch that,” I said. “To see people either that lonely or that desperate to be on TV would only make me sad.”

“There’s that, of course,” he conceded, “but when you think about it, that’s how your great-grandparents met. And I’ve often wished I could arrange marriages for you and Charlie.” I prudently decided to not interpret this as a dig at any of our romantic partners. I suppose he wasn’t wrong about the matchmakers, but it does seem that, with parties of identical upbringings and cultural mores—not to mention not much premium placed on modern marital happiness—the shtetl varietal had a somewhat easier time of it.

Not that it was always so great. In the case of my grandmother’s parents, Great-Grandma Ida forced her husband to sleep on the floor of his shop and apparently taunted him with tales of her vastly superior, tall, handsome, old-country sweetheart.

On the Stein side, things were more pacific, but it amazed everyone that this should be so: my great-grandfather was universally adored, while, even fifty years after her death, Great-Grandma Emma’s daughters-in-law described her as a hideous termagant. As Woody Allen would have it, “the heart wants what it wants.”

On a recent subway ride, the female passengers were universally menaced by a creep who drifted around the car, stroking our hair and arms and then grinning broadly and pointing at his chest. His shirt read, “Let’s Get Engaged.” No one seemed tempted. And then some guys threw him off the train, which is a little unfair when you consider that other people get TV shows.

A footnote: After my great-grandfather’s death, it turned out that the famous one-that-got-away had been living, all the time, a few Bronx blocks away, and was himself widowed. The day he came to call, Great-Grandma Ida’s children gathered in fascination, eager to see this paragon. And? “Well,” said my great-aunt, Rose, shortly before her death. “He was even shorter than Papa!” Great-Grandma Ida was apparently similarly unimpressed, or he was; she remained a widow until her death.

I wonder if one day I’ll be reduced to telling my grandchildren, “I had options, you know. I had choices. There was one man who proposed to me on the subway! I’ve always wondered what might have happened if I’d taken a chance and said yes …”

I Remember Georges Perec

“I remember that Stendhal liked spinach.” Stendhal, Olof Johan Södermark, 1839, oil on canvas.

I remember reading Joe Brainard’s accumulated aphoristic memories for the first time. I remember the way each entry built on the one that preceded it, even when they had little to do with each another, and I remember the texture of the entire enterprise: a pointillist portrait of a man by way of his internal dialogue; his observations, at one time absorbed as impressions, sent back out into the world, now shaped by a unique river of associations.

I can only imagine the extent to which Brainard’s I Remember has influenced writers since he penned his flowing juxtapositions forty-four years ago. I had long thought Édouard Levé’s Autoportrait the most obvious example—a seemingly endless sequence of declarative sentences that coolly relate both trivialities and intimacies. But I’ve now discovered that Georges Perec got there first.

In 1970, Perec met Harry Mathews; Mathews introduced Perec to ideas then circulating in the New York art scene, including Brainard’s “serial autobiography,”

which was then on the cusp of publication. The French writer likely never saw Brainard’s book, but tale of its concept—each sentence beginning with the phrase “I remember”—was enough to inspire him. Next month, the fruits of Perec’s efforts, also titled

I Remember

, will be published in English for the first time, by David R. Godine.

Perec first began the exercise as a parlor game at a writers’ retreat and added a twist to the formula, insisting, David Bellos explains in his introduction to the book, that players “had to remember something that other people could remember too; and the thing remembered had to have ceased to exist.” On his own, Perec stuck to this conceit and produced 480 “I remembers” (some of which were published in 1976, in the journal Cahiers du Chemin). They were written between January 1973 and June 1977 but are pulled from the time when Perec was between ten and twenty-five years old. His aim was to unearth memories that were “almost forgotten, inessential, banal, common, if not to everyone, at least to many.” At the same time, he could not always guarantee veracity in his statements: “When I evoke memories from before the war, they refer for me to a period belonging to the realm of myth: this explains how a memory can be ‘objectively’ false.” (Put another way, memory’s a funny thing.)

Perec’s version of “I remember” has a very different feel from Brainard’s and Levé’s (though Autoportrait does contain the line “When I was young, I thought Life: A User’s Manual would teach me how to live”): where Brainard and Levé meander the alleyways of memory, Perec stands in the boulevard; he evokes a communality of memory, but of course one whose perception has its origin in a single individual—himself.

It’s a wonder that this book is only now making its way into English. Philip Terry took on the task of translating Perec’s word games, puns, and jokes. “If it looks easy,” Terry writes, “I should be especially wary.” But even if the reader misses cultural references or overlooks one of Perec’s jokes, the effect of cascading “I remembers” is unavoidably mesmerizing. Which, in the end, seems to be one of Perec’s aims. Memory 480 simply reads “I remember… (to be continued…)”—after which appear a dozen or so blank pages that have been inserted at Perec’s request, so that the reader can record his or her own “I remembers.”

244

I remember that Stendhal liked spinach.

245

I remember the Lépine Contest.

246

I remember that Citroën used the Eiffel Tower for a gigantic illuminated advertisement.

247

I remember that de Gaulle had a brother called Pierre who ran the Foire de Paris.

248

I remember the Finaly affair.

249

I remember the young actor Robert Lynen, who appeared in Poil de Carotte and in Carnet de bal (in which he had a very small part) and who died at the beginning of the war.

250

I remember the assassination attempt at Petit-Clamart.

251

I remember the cinema Le Studio Universel in Avenue de l’Opera, which specialized in animation festivals.

252

I remember that Lester Young was nicknamed “The Prez” and Paul Quinichette “The Vice-Prez.”

253

I remember that SHAPE stood for the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe.

254

I remember Bouvard and Ratinet log tables.

255

I remember the murder of Sharon Tate.

256

I remember that the principal victims of McCarthyism in the world of cinema were the filmmakers Cyril Entfield, John Berry, Jules Dassin, and Joseph Losey, as well as the script-writer Dalton Trumbo. All of them went into exile, except Dalton Trumbo, who was obliged to work under assumed names for several years.

257

I remember that Audie Murphy was the most decorated American soldier of the Second World War and that he became an actor after having played himself in a (mediocre) film recounting his heroic exploits.

258

I remember that James Stewart played the part of Glenn Miller in the biopic of this jazz musician whose most famous piece is “Moonlight Serenade.”

259

I remember that one of the first decisions that de Gaulle took on coming to power was to abolish the belt worn with jackets in the military.

260

I remember that the four sentences written on the pediments of the Palais de Chaillot were composed specially by Paul Valéry.

261

I remember that once the counter and the kitchen area of the restaurant La Petite Source in Boulevard Saint-Germain were situated on the right of the entrance and not, as now, on the left in the back.

262

I remember that Julien Gracq was a history teacher at Lycée Claude-Bernard.

263

I remember President Rosko.

264

I remember a dance called the raspa.

265

I remember Lee Harvey Oswald.

266

I remember beard tennis: you counted the number of beards you spotted in the street: 15 for the first, 30 for the second, 40 for the third, and “game” for the fourth.

267

I remember the song:

“Ramadjah my Queen

Ramadjah my clot

Dip your arse in the soup tureen

And tell me if it’s hot.”

268

I remember that during his trial Eichmann was enclosed in a glass cage.

269

I remember the boxer Ray Famechon, as well as Stock and Charron, and quite a few wrestlers (The White Angel, The Béthune Butcher, The Little Prince, Doctor Adolf Kaiser, etc.).

270

I remember the Markowitch Affair.

271

I remember the strips of mica or celluloid that people used to fix on the front of their hoods (near the radiator cap) and which stopped mosquitoes and aphids from hitting the windscreen.

272

I remember that the three star dancers of the Paris Ballet were Roland Petit, Jean Guélais, and Jean Babilée.

273

I remember that Saint Crispin and Saint Crispinian are the patron saints of shoe-makers.

From I Remember by Georges Perec, Translated from the French by Philip Terry. Copyright © Georges Perec 2014, Translated from the French by Philip Terry.

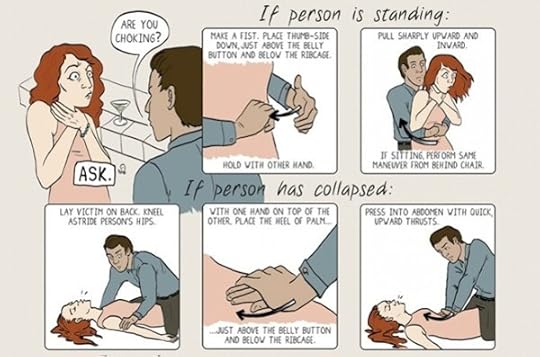

Give the Heimlich in Style, and Other News

The artist Lara Antal’s custom-designed choking poster for Sunshine Co. Image via MICA

At the New York Public Library, a copy of Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique (1926), once known as “the best-selling sex manual of all time,” was returned nearly fifty-four years late. Carnal knowledge takes time.

New York City requires its restaurants to “have posted in a conspicuous place, easily accessible to all employees and customers, a sign graphically depicting the Heimlich maneuver,” but the city’s official poster isn’t exactly pleasing to an aesthetic eye. “Restaurants citywide are increasingly turning to boutique posters to blend in with their overall look, so far without drawing the ire of health inspectors.” Graphic designers sell these for as much as eighty bucks.

“The paranoid logic of the censoring mentality” makes sense only if one believes that readers are morons.

“The Internet has been the most dramatic change in the lives of blind people since the invention of Braille. I can still remember having to go into a bank to ask the teller to read my bank balances to me, cringing as she read them in a very loud, slow voice … tech-savvy blind people were early Internet adopters. In the 1980s, as a kid with a 2400-baud modem, I’d make expensive international calls from New Zealand to a bulletin-board system in Pittsburgh that had been established specifically to bring blind people together. My hankering for information, inspiration, and fellowship meant that even as a cash-strapped student, I felt the price of the calls was worth paying.”

In 2008, a seventeen-year-old changed the Wikipedia entry on the coati, a kind of raccoon that he claimed is also known as “a Brazilian aardvark.” References to this fabricated nickname “have since appeared in the Independent, the Daily Mail, and even in a book published by the University of Chicago … [The claim] still remains on its Wikipedia entry, only now it cites a 2010 article in the Telegraph as evidence … This kind of feedback loop—wherein an error that appears on Wikipedia then trickles to sources that Wikipedia considers authoritative, which are in turn used as evidence for the original falsehood—is a documented phenomenon. There’s even a Wikipedia article describing it.”

July 29, 2014

Incident / Resurrection

Roxy Paine, Incident / Resurrection, 2013; 6' 9 9/16" x 15' 11 1/4" x 10"; neon. On display through August 15 at Paul Kasmin Gallery.

My commute takes me past Paul Kasmin Gallery, at the corner of Twenty-seventh and Tenth, less than a block from The Paris Review’s offices. Every morning for the past month, I’ve paused there to stare at an installation through the window, a pair of illuminated silhouettes. I watch as one red neon man thwacks another with a red neon two-by-four. Every time, the second red neon man falls to the ground; every time, he rises again, on hands and feet, retracing the ungainly arc of his fall; and every time, the first red neon man thwacks him again.

Thwack, fall, rise, repeat. Like many forms of suffering, this one goes on ad nauseam—and like many forms of suffering, it burns itself into your retinas. I watch the cycle four or five times and then walk the two-thirds of a block to the office carrying an afterimage of neon trauma. I find this strangely buoyant.

Only today, after more than a month of doing this, did I decide to find out what exactly I’d been seeing. It’s Roxy Paine’s Incident / Resurrection (2013), which the artist’s website characterizes as “a visual loop of pure narrative movement”:

Inspired by a random act of violence the artist experienced in Brooklyn in 1987, the work transcribes a story about reason and the absence of reason. To Paine, when randomness like this occurs, it is a sudden interruption of the social order of things—a deeply troubling moment about human nature and the primal brain stem.

The sequence, riveting and disquieting, takes on weight with repeated viewing. People in accidents often speak of how everything in those moments seems to unfold beat by beat: Paine’s work has this staggering, stop-motion quality. The warm halo of the red tubes, the perpetually alert stance of the assailant, the victim’s momentary fringe of disheveled hair. How sad that the second silhouette must inevitably fall to that two-by-four, but how encouraging that he inevitably finds the wherewithal to pick himself up again. Sometimes it seems to me that he’s in perfect control of his fate, facing the pain with grace and forbearance—he’s practically dancing. Other times, he’s just a chump.

It’s no accident, I’m sure, that the work is visible from the street, from public space, where an unfortunate viewer may well incur “a random act of violence” not unlike the one represented here. And that’s part of the larger context of the exhibition, I’ve learned: Incident / Resurrection appears at Paul Kasmin as part of Phong Bui’s “Bloodflames Revisited,” designed in tribute to the seminal “Bloodflames” exhibition of 1947, directed by Alexander Iolas at Hugo Gallery:

“Bloodflames” presented works by Arshile Gorky, Matta, Isamu Noguchi, and Jean-Claude Reynal among others. [Frederick] Kiesler’s design called for an unconventional exhibition construction, wherein artworks were projected and tilted at various angles from the gallery walls, to allow uncommon perspectives of view. His bold architectural interventions dissolved the barrier between viewer and artwork.

“Bloodflames Revisited” appears through August 15; even if you don’t cross the gallery’s threshold, it’s worth visiting just to let Incident / Resurrection wash over you for a few minutes. Or a few hours, even.

Goodnight House?

121 Charles Street, in Greenwich Village.

The optimists among us may think we’re okay: the world will sort itself out, the climate will stabilize, young people will always read and dream and give us hope for the future. And yet, sometimes you see something so objectively depressing that it’s hard not to feel we’re doomed. Case in point: 121 Charles Street, in Manhattan, also known as Cobble Court.

The property, an eighteenth-century farmhouse, is noteworthy for its charm—it’s surrounded by a pretty yard on a picturesque Greenwich Village street. Peep through the fence and you can see the little white birdhouse made in the larger house’s image. Not original to the neighborhood, in 1967, it was moved from York Ave. and 71st Street to avoid demolition.

Horribly enough, it is imperiled again: a broker recently listed it as a “development site” for $20 million. Quoth they,

ERG Property Advisors is pleased to exclusively offer for sale a West Village development site located at 121 Charles Street on the corner of Charles and Greenwich. The property is directly situated in arguably the most desirable enclave in all of Manhattan, the West Village. The property’s corner location benefits from significant frontage along both Charles and Greenwich Street … creating tremendous street presence. The property consists of a 4,868 square foot corner lot in the Greenwich Village Historic District. The offering would allow a developer or user to execute a wide variety of potential visions, from boutique condominiums, apartments or a one-of-a-kind townhouse.

Hopefully, its age and value will help preserve it. Andrew Berman of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation declared that anyone attempting to demolish the house “would have a mighty fight on their hands … This is one of the most beloved and historic corners of the Village. We and many others would fight very hard to keep it that way.” While the house is located within the Greenwich Village Historic District, its status as “contributing” is somewhat complicated by its twentieth-century move.

But its value isn’t just historic, or even aesthetic—not that these shouldn’t be enough. Margaret Wise Brown, the author of Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny, lived in the house in the 1940s. (Some say she wrote Goodnight Moon there; I’ve read varying accounts.) Even if you are one of those who, like the Curbed commenter “Captain Cranky,” considers the house “a shed built by drunks,” it’s hard to imagine anything that went up in its place would be an architectural masterpiece—and lord knows there are plenty of similar structures popping up in this wealthy neighborhood to give you the idea.

When she was interviewed in late life, Jane Jacobs, who’s widely credited with having saved Greenwich Village from development, said, “I think that things are getting better for cities in that there’s not the great ruthless wiping away of their most interesting areas that took place in the past. Terrible things were happening when I wrote Death and Life, so that’s an improvement.” Jacobs died in 2006.

On the other hand, we have Captain Cranky: “You people would ‘save’ a home built from pallets and old shower curtains if it was old. Garbage is garbage regardless of history.” Which, while not exactly the same as optimism, must certainly save one a lot of heartbreak—if not choler.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers