The Paris Review's Blog, page 677

August 4, 2014

To Serve and Protect

Not, alas, an actual archival photo.

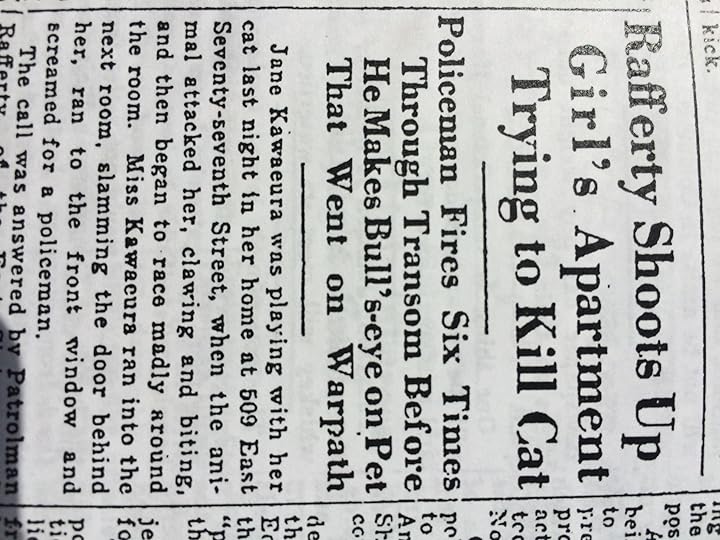

“Cats Hate Cops” is a tidy black-and-white pamphlet from Research & Destroy, a “radical zine collective” based in New York. Its title may seem, to the casual observer, like an editorial statement, but make no mistake: it’s a fact. The zine’s sixty-two pages comprise 150 years of cat-on-cop violence, all of it diligently chronicled by our nation’s newspapers—hard evidence, in other words. The first report is from 1805, when, in Edinburgh, a man attempting to police his dairy met with a cat bite on the neck; the latest is from the Melbourne Age, which last January ran a sidebar called “Anatomy of a Cat Attack.” (“Police close one lane and engage Scratchy, who resists.” Attaboy, Scratchy!)

Whether these are disconnected incidents or the enactment of a kind of feline political philosophy remains to be seen, but my money’s on the latter. It just makes sense. Cats and humans are coevolved; the Scratchys and Tigers of the world have had ample time to form opinions about authoritarianism and the police state. And think about it: Have you ever seen a cat driving a cruiser? Have you even once seen a cat with a badge? These animals want Friskies, not frisking.

Of course, the media tends to side with the state. “A mad cat upset the general routine of things last Friday morning at a grocery store,” reads a 1939 blurb, failing thereafter to give the cat’s point of view. Time and again, “Cats Hate Cops” describes a world in which the humane treatment of animals is not a going concern, and in which the police are generally assumed to be competent executors of the public will. The prose is often blunt: “After clubbing the animal into insensibility they shot it through the head,” one story ends.

The zine is available from Brown Recluse Zine Distro; below are two of my favorite entries.

Poetry in Motion

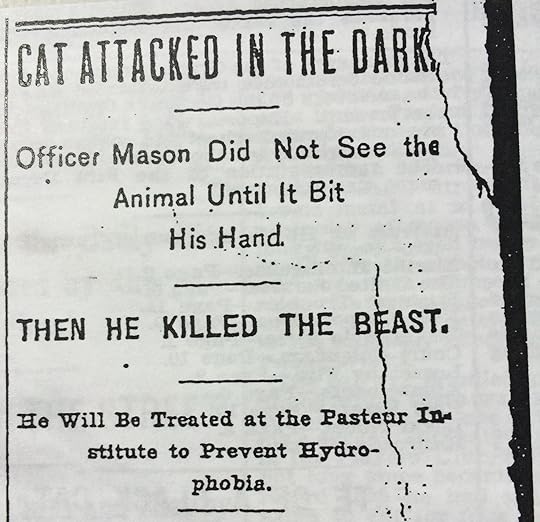

The Brooklyn Bridge in 1892.

Yesterday, I decided to walk home across the Brooklyn Bridge. With this in mind, I had downloaded a fine recording of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” before setting off, and planned to commune with Whitman, or whatever, as I marched, marveling at the ceaseless roll of existence and the beauty of the language and, if I felt like it, crying a little. There was absolutely no question in my mind that this was a fantastic idea.

FLOOD-TIDE below me! I watch you face to face;

Clouds of the west! sun there half an hour high! I see you also face to face.

Which was all very well, except that I’d forgotten that in fine weather the pedestrian thruway is so crowded that it’s almost impassable. People like to stop and take pictures—of themselves, or with others, or by others—and you can hardly blame them for it. Not that there’s anything wrong with visiting the Brooklyn Bridge! On the contrary! It’s beautiful, it’s historic, it’s free, and walking the mile-plus span is good exercise! But it gets in the way of the idyll, a little. Undeterred, I put in my earbuds and started walking.

It avails not, neither time or place—distance avails not;

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence;

I project myself—also I return—I am with you, and know how it is.

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt;

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd;

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d;

Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood, yet was hurried;

Just as you look on the numberless masts of ships, and the thick-stem’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

I was feeling deeply moved when a nice group of Germans asked me to take their picture. I paused my recording—“I was Manhattanese, friendly and proud!”—and took a few, just to be safe.

Now I am curious what sight can ever be more stately and admirable to me than my mast-hemm’d Manhattan,

My river and sun-set, and my scallop-edg’d waves of flood-tide,

The sea-gulls oscillating their bodies, the hay-boat in the twilight, and the belated lighter;

Curious what Gods can exceed these that clasp me by the hand, and with voices I love call me promptly and loudly by my nighest name as I approach;

I almost walked into a Japanese wedding party. Trying to step around them, I incurred the wrath of a biker.

Curious what is more subtle than this which ties me to the woman or man that looks in my face,

Which fuses me into you now, and pours my meaning into you.

We understand, then, do we not?

What I promis’d without mentioning it, have you not accepted?

What the study could not teach—what the preaching could not accomplish, is accomplish’d, is it not?

What the push of reading could not start, is started by me personally, is it not?

I encountered a group of Spaniards, one of whom was wearing a shirt that read “Learn how to entertain an idiot! See back of shirt.” As I passed him I duly inspected the shirt’s reverse. “Learn how to entertain an idiot! See front of shirt,” it said. Since he was the one blocking the walkway so as to take a picture of the bridge’s suspension such as might be found on a million postcards, I thought that was a bit rich. (“Crowds of men and women attired in the usual costumes! how curious you are to me!”) Also, now I had lost my place.

Flow on, river! flow with the flood-tide, and ebb with the ebb-tide!

Frolic on, crested and scallop-edg’d waves!

Gorgeous clouds of the sun-set! drench with your splendor me, or the men and women generations after me;

Cross from shore to shore, countless crowds of passengers!

Stand up, tall masts of Mannahatta!—stand up, beautiful hills of Brooklyn!

Throb, baffled and curious brain! throw out questions and answers!

Suspend here and everywhere, eternal float of solution!

Gaze, loving and thirsting eyes, in the house, or street, or public assembly!

Sound out, voices of young men! loudly and musically call me by my nighest name!

Live, old life! play the part that looks back on the actor or actress!

Play the old role, the role that is great or small, according as one makes it!

Then, of course, I ran into someone I went to high school with. She was running; I was standing around listening to a recording of a poem, and weeping. It seems she is now practicing family law, married, and living in Carroll Gardens.

You have waited, you always wait, you dumb, beautiful ministers! you novices!

We receive you with free sense at last, and are insatiate henceforward;

Not you any more shall be able to foil us, or withhold yourselves from us;

We use you, and do not cast you aside—we plant you permanently within us;

We fathom you not—we love you—there is perfection in you also;

You furnish your parts toward eternity;

Great or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul.

On the Manhattan side, there were vendors selling souvenirs. I stopped to look at them for a moment; a guy offered me an especially good deal on an “I ♥ New York” shirt. “Thanks, I’m good,” I said, even though I kind of wanted it.

Bad Call

The growing redundancy of sports commentary.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

You’re gonna have to learn your clichés. You’re gonna have to study them, you’re gonna have to know them. They’re your friends. Write this down: ‘We gotta play it one day at a time.’

—Bull Durham

They smelled the jugular.

—Sportscaster Chris Berman, during the 2002 NFL playoffs

In 1945, George Orwell’s “The Sporting Spirit” appeared in the leftist weekly Tribune. The essay argued that large-scale athletic competition, rather than creating a “healthy rivalry” between opponents, is more likely to rouse humanity’s “savage passions.” Thus: “There cannot be much doubt that the whole thing is bound up with the rise of nationalism—that is, with the lunatic modern habit of identifying oneself with large power units and seeing everything in terms of competitive prestige.”

To a contemporary reader, Orwell’s assessment of the “sporting spirit” may feel exaggerated, if not slightly paranoid. Then again, in an age of rampant merchandising, zealous fandom feels more pervasive than ever. Not long ago, riding the subway, I saw an infant with a San Francisco 49ers pacifier; in the same car, there was a man wearing an Ohio State football sweater bearing the laconic slogan, “Fuck Michigan.” What Orwell might have thought of such displays of allegiance is anyone’s guess.

But what he would find troublesome is sports culture’s continued abasement of the English language. Professional sports jargon has become so vacuous that TV interviews with athletes are increasingly farcical—and tremendously boring. An interview with LeBron James, after a botched play at the end of a quarter:

INTERVIEWER: Lebron, what happened with you and Norris on that inbounds pass?

JAMES: We didn’t execute.

INTERVIEWER: You were talking to him as you guys walked off the floor. What did you say?

JAMES: That we need to execute better.

Perhaps such vagueness is intentional: if LeBron James had, in fact, just told his teammate that if he makes the same mistake again he’s going to rip his face off, he’d be disinclined to share it with a national audience. For similar reasons, a coach interviewed at halftime isn’t going to be too forthcoming when asked to reveal his strategy for the remainder of the game: “Well, Chris, we’ve just gotta keep pressuring their quarterback and not make any unnecessary mistakes.”

David Foster Wallace puts forth a more cerebral take on this trend in his essay “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart.” Wallace was fascinated by pro athletes—they could “execute” under insane pressure and, asked afterward how they did it, would resort to clichés:

How can great athletes shut off the Iago-like voice of the self? How can they bypass the head and simply and superbly act? How, at the critical moment, can they invoke for themselves a cliché as trite as “One ball at a time” or “Gotta concentrate here,” and mean it, and then do it? Maybe it’s because, for top athletes, clichés present themselves not as trite but simply as true, or perhaps not even as declarative expressions with qualities like depth or triteness or falsehood or truth but as simple imperatives that are either useful or not … Those who receive and act out the gift of athletic genius must, perforce, be blind and dumb about it—and not because blindness and dumbness are the price of the gift, but because they are its essence.

It’s a seductive idea, but ultimately unconvincing. Suggesting that blindness and dumbness are the “essence” of their genius is to ignore that pro athletes hardly hold a monopoly on inarticulateness—theirs just gets a disproportionate amount of media coverage. Most of us are sadly inept when it comes to self-expression. And if, as Wallace suggests, spectators are the only ones able to articulate athletic genius, why is it that TV commentators, who should be the most well-informed and passionate spectators of all, are responsible for the most mundane platitudes in professional sports?

If you, like me, spend an irrational amount of your fleeting time on Earth watching huge men brutalize each other in hi-def, you’ll know what I’m talking about: “It’s hard to overstate what this win means for this organization”; “He’s got tremendous basketball IQ”; “You can feel the momentum swinging”; “They’re a real Cinderella story”; “They’ve got that championship swagger”; “They stepped up and made plays”; “These guys have to keep their continuity”; “He makes his presence known on the field.” Et cetera. The silliness of these stock phrases becomes more apparent in a nontelevised context. The next time you get into a heated sports debate, try describing your favorite athlete as “an absolute specimen with great physicality.” For maximum effect, keep a serious expression and maintain eye contact.

In fairness to the Marv Alberts of the world, sportscasting requires live commentary on the same activity, night after night, season after season. How realistic is it to expect linguistic ingenuity? Criticizing a sportscaster’s lack of originality might be as obnoxious (and pointless) as lamenting the uninspired prose of the user manual that came with your new toaster.

Which makes me wish I could ignore the current trend in redundancy that has seemingly infected every foot- and basketball announcer on TV. These commentators have developed a verbal tic that compels them to remind the viewer, constantly, which sport is being discussed. Basketball players with consistent jump shots are no longer just good shooters—they’re “good at shooting the basketball”; astute quarterbacks are commended for calling out “excellent football plays.”

If you’ve been exposed to this verbosity for long enough, it no longer sounds bizarre. To the uninitiated ear, though, it’s hard to ignore. I was watching a football game with a friend when the commentator announced that “this offense loves to run the football.” My friend: “Why don’t they just say ‘run the ball’? What other kind of ball is it going to be?”

Conversely, a new shorthand has oozed its way into the parlance of professional and college basketball: centers and taller forwards are now referred to as “bigs,” while a team that prevents their opponent from scoring on a possession has made a “stop.” After a losing effort, coaches and players will now offer this Neanderthal explanation: “We really needed to get more stops, but their bigs really stepped up and made plays. That cost us the basketball game.”

After a prolonged TV spectacle like college football’s Bowl Week (whose contests last year included the Buffalo Wild Wings Bowl and the Taxslayer.com Bowl, the latter being only a slight improvement on the all-time most absurd Galleryfurniture.com Bowl), watching English Premiership matches or Six Nations rugby on BBC feels like a cultural upgrade. There’s less advertising. There’s less analysis of bullshit statistics (“Headed into this matchup, the Kentucky Wildcats are 11-3 in games played within four days of their coach’s annual colonoscopy”). And, on British television, the commentators’ linguistic repertoires don’t feel as inhibited; there’s more room for an occasional flourish. Why can’t we have a color analyst like Ray Hudson, who, in his exuberance, will announce that we’ve just witnessed “a Bernini sculpture of a goal,” or claim that watching Lionel Messi “softens the hard corners of our lives”?

Surely the hollow phrasings of play-by-play announcers aren’t comparable to instances where bad language is truly malevolent, as when despots employ euphemism to conceal mass murder. The latter is a concern of Orwell’s most famous essay, “Politics and the English Language,” where he argues that much political speech and writing has become a “defense of the indefensible.” But he also insists that the decay of language can be combatted, and that it is necessary to do so, since “bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation even among people who should and do know better.” If this fight against banal language isn’t to be confined to the political sphere, then we’d be well advised to choose our words with care, even, and perhaps especially, when we’re discussing harmless distractions.

Fritz Huber is an editorial assistant at Outside Magazine.

This Old Phallus Tree, and Other News

A nun picks ripened penises from a phallus tree in the Roman de la Rose, ca. 1325–53. Image via Collectors Weekly

Curmudgeons avow that the text message, with its relentless abbreviations and disdain for punctuation, is vandalizing our language. But that loose style has been around for centuries: “modern text-speak bears a striking resemblance to the system of abbreviations and shorthand present in medieval manuscripts.” (Haha, for instance, made an appearance on vellum as early as 1000 AD.)

Also appearing in medieval manuscripts: illustrations of flatulent monks, killer rabbits, an ogre with an anal fixation, and a nun plucking penises from a phallus tree.

In which Geoff Dyer attends an academic conference devoted to Geoff Dyer. “‘When speaking about the work, use Dyer,’ urged Dr. Bianca Leggett, the convenor of the conference, in her opening remarks. ‘When speaking about the man in the room, use Geoff.’ ”

“Partisan Review is remembered for the editorial vision of two of its founders, William Phillips and Philip Rahv … but a third founder of the magazine, poet and thriller-writer Kenneth Fearing, has been largely forgotten, in part because he was suspected of being a Communist, and in part because he wrote thrillers.”

Paris Review contributor Kristin Dombek turns her advice column into a meditation on political economy: “You have been trained from childhood to think that labor, in and of itself, is both a right and one of the most important goals of your life; you have been told that your ‘career’ is the same thing as ‘who you are in the world.’ Yet like most employed people in the United States, you work jobs that you consider to be banal, brutal, or both. For this labor you are supposed to be grateful, since work is increasingly hard to get: if you lose your shitty job, you’ve got only a one-in-five chance of finding a new one … ”

August 1, 2014

What We’re Loving: Slugs, Sluggers, Suet Pastry

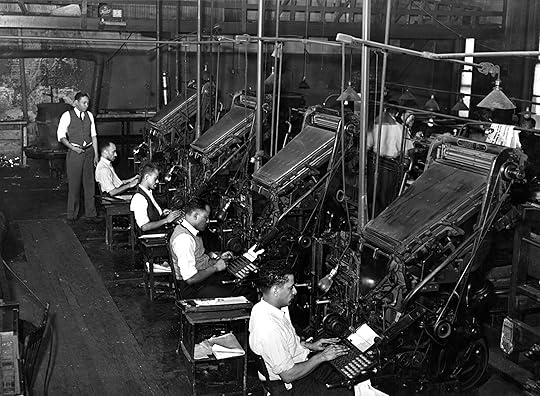

Linotype operators of the Chicago Defender, 1941. Photo: Russell Lee

Have you ever been reading, say, a George Eliot novel and suddenly wondered how the dry cleaning worked? Or what everyone used for toothpaste? Or how the farm women managed to do all that mowing in corsets? If this is the sort of question that interests you, prepare to be engrossed by Ruth Goodman’s How to Be a Victorian: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life. No doubt some material will be familiar to viewers of Goodman’s BBC series, Victorian Farm, Edwardian Farm, and Victorian Pharmacy; having spent so much time costumed, cooking, and laboring for the camera, Goodman is terrific at describing the feel of heavy worsteds, or the craving for suet pastry, or the manual skills that she admires in Victorian men and, especially, women. Her admiration is contagious and, often, unexpectedly moving, as we see workmen tending to their gardens or little girls learning, from a magazine, how to sew by “dressing dolly.” This is cultural history even a kid could understand, and that (I suspect) even a scholar might enjoy. —Lorin Stein

Roger Angell received the baseball Hall of Fame’s award for writers last week, and I’ve been reading through Game Time, one of his many Baseball Companions. Angell had a way of getting players, especially pitchers, to talk about their craft with detail and clarity—they’re all philosophers of the game, as well as practitioners. In “Easy Lessons,” a piece about spring training in 1984, Angell talks with some older players who were winding up their careers. A thirty-seven-year-old Reggie Jackson says, “I often think about coming to the end. It’s fairly real—it’s a possibility—and I can’t say it doesn’t bother me.” Tom Seaver and Don Sutton talk pitching mechanics with a courtly, conversational style that is just like Angell’s. With the Mets permanently stuck at five games under .500, it’s a relief to revisit seasons past. —Robyn Creswell

My grandfather worked as a linotype operator, carefully managing sorts and slugs (tiny letters and spaces cast from molten lead) to bring words into type. By definition, this meant he was a comprehensive and intimate reader of countless newspapers, books, and pamphlets over the course of his career, which saw the height of mechanical typesetting and its subsequent decline at the hands of electronic automation. What began as a highly sought-after union job—one that allowed him to travel widely, working for presses in the U.S., Ireland, and Australia—had essentially dried up by the time he retired at fifty-five. So I was heartened when I saw the meticulous shots of lead-letter type and mechanical printing presses and pigs (blocks of lead from which new type is molded) in a PBS feature on Arion Press, one of the last presses dedicated to making books by hand, with hot metal typesetting on handmade pages and hand-sewn bindings. Arion is currently working on a special edition of Leaves of Grass—Whitman, a literary champion of the common man working with his hands, seems a fitting choice for this project. At Arion, you can see some of the last hand-typesetters on Earth, dedicated to an art that is all but lost. There are no big victories to be had against digitization, against the steady decline of books as treasured objects, as things to hold rather than screen sequences to be “46 percent done” with. There are only small, futile acts of defiance, and tiny letters made of lead. The full segment, which includes an interview with former poet laureate Robert Hass, airs tonight on PBS. —Chantal McStay

Though I already quoted it at length in this morning’s news roundup, I can’t endorse Rebecca Mead’s latest column for The New Yorker, “The Scourge of ‘Relatability,’” enough. The word relatable was once the province, Mead explains, of daytime talk-show hostesses—the word conjures manicured executives passing glossy focus-group results around a glass conference-room table. (“Will it play in Peoria?” Hollywood bigwigs used to ask, which amounts to the same concern.) But art and literature aren’t, or shouldn’t be, in the thrall of commerce. Why, then, do so many readers, including nominally intelligent ones like Ira Glass, insist that relatability is a valuable metric? “To demand that a work be ‘relatable’ expresses a different expectation: that the work itself be somehow accommodating to, or reflective of, the experience of the reader or viewer,” Mead writes; “the notion implies that the work in question serves like a selfie: a flattering confirmation of an individual’s solipsism.” Is this all we want from our artists—affable, familiar depictions of everything we already recognize? If you’re a reader who treasures relatability above all else, I can’t relate to you at all. This may mean I should read a novel about you, but let’s continue not to be friends. —Dan Piepenbring

Decades after its publication, The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake continues to mystify writers and readers. When I came across the collection my sophomore year in college, everything about it intrigued me: the name, Pancake’s suicide, the Pulitzer nomination many years after his death. The stories themselves were raw, haunting, and beautiful—as Kurt Vonnegut wrote to John Casey, “What I suspect is that it hurt too much, was no fun at all to be that good. You and I will never know.” In the Oxford American, Marion Field recalls her parents’ relationship with Pancake during his graduate studies at the University of Virginia. He was a conflicted outsider whom everyone respected, a manipulator who wanted to be understood. “He kept ghosts for company and couldn’t explain to the khaki-wearing set what haunted him. It was more than the fiction alone and more than the grief of his real life.” —Justin Alvarez

“Manfeels Park,” a feminist web-comic, pairs scenes from Jane Austen novels with a slew of sexist comments from various quarters of the Internet, usually from “hurt and confused men with Very Important Things to Explain.” This week’s edition, “Austen Characters Against Feminism,” satirizes the now infamous Women Against Feminism tumblr. My favorite strip highlights Lizzy Bennet herself—Austen’s most beloved heroine wasn’t having your chauvinism then, and she isn’t having it now. “I don’t need feminism because he loves me against his will, against his reason, and even against his character,” she says. “No, wait…” —Yasmin Roshanian

Fruit Mutiny

Whither the breadfruit?

Marguerite Girvin Gillin, Breadfruit, ca. 1884

There’s such a thing as the Breadfruit Institute, and there should be. Researchers consider the species a “NUS”—“neglected and underutilized species.” But Ian Cole, the Breadfruit Institute’s collection manager, thinks that’s insane. He told me, “If you had a breadfruit tree in your yard, you would have food all year round!”

I don’t have a breadfruit tree in my yard, though, and neither do you, if you live in the lower forty-eight. Cole wants that to change. He wants the world to eat breadfruit.

He may well get his wish. Breadfruit, a starchy fruit that looks like a green pimpled softball, is enjoying a bout of sudden popularity. It’s gluten free, dense with protein, and rich in vitamin B and fiber. It has the mild, earthy flavor of a tuber. And it looks pretty neat: what appears to be a singular globe of fruit is in fact thousands of tiny fruits fused together like a mosaic. The media is in thrall. The Daily Mail calls breadfruit “a wonder food”; the Huffington Post calls it “a wonder food”; and the New Scientist calls it “a wonder food.” The New Zealand Herald asked in a recent news headline, “Is this the new wonder food?” Yes. Yes, it is.

Since a single tree yields 450 pounds of fruit a year, some say breadfruit can feed the world; others see fermented breadfruit flour as a gluten-free alternative to ordinary flour. Medical researchers are intrigued by “its potential chemopreventive abilities,” which is to say that breadfruit reduces inflammation in mice. The breadfruit tree produces a sticky substance that can be used as caulk or glue. Its wood is relatively immune to termites. Burning breadfruit leaves creates an ideal mosquito repellant.

The USDA has no data on breadfruit. There’s no need for it. But in Hana, Maui, where Cole tends 120 varieties of breadfruit trees from thirty-one Pacific islands, genetic diversity is carefully documented and nurtured on centuries-old verdant groves. Cole, along with several other local breadfruit farmers, sells fruit to nearby restaurants and hotels, and to a pie company. Two of his more interesting trading partners are his mechanic, who fixes Cole’s tractors in exchange for breadfruit, and a local “artisan pig farmer” who feeds blemished breadfruit to his swine. (“I need to get him a tree,” Cole reminded himself as we talked.)

But the ambition here goes well beyond neighborly exchange. Cole envisions breadfruit becoming a more sustainable version of corn, soy, wheat, or rice. By his account, breadfruit is an eco-friendly feedstock—fuel for the industrial food system, where it could help with reforestation, feeding animals and humans alike without losing its character to genetic modification or trashing the planet. Considering the prospect of this transition, Cole said, “It’s pretty awesome, actually.”

The breadfruit went global during that extended bio-prospecting carnival known as colonization, when imperial regimes, unburdened by the fear of “invasive species”—or much of anything, for that matter—realized that what God had sown on alien soil was more valuable than what was cached beneath it.

Captain Cook and Sir Joseph Banks, the preeminent English naturalist, initiated the breadfruit’s jagged path across the globe. It’s native to South Pacific islands ranging from Papua New Guinea to Western Micronesia; Banks first encountered it in Tahiti in 1769, where it must have been hard to miss. Tahitians had devised an idiosyncratic preservation technique: they loaded the breadfruit in woven bags, soaked them in the ocean, and stomped on them for hours in the crashing surf. Chiefs wore elaborate robes woven from breadfruit fiber—they called the cloth “tapa.” Islanders peeled breadfruit with seashells and wrapped them in banana leaves.

Upon his return to London, Banks raved about breadfruit to King George III, who was otherwise occupied with keeping his North American colonies in the fold of empire. It wasn’t until Banks promoted the breadfruit as an ideal source of cheap starch for English-owned slaves on West Indian sugar plantations that the King pricked up his ears, snapped his fingers, and summoned an explorer.

Two Tahitian men preparing breadfruits in the early twentieth century.

The gig went to Captain William Bligh—a.k.a. Breadfruit Bligh, who in 1787 sailed the H.M.S. Bounty to Tahiti, where he and his crew sowed and harvested and stowed 1015 breadfruit saplings to ship to the West Indies. A few days into the journey, a mutiny—the famous Mutiny on the Bounty—occurred. The mutineers had taken up with Tahitian women and wanted to go back, go native, and start a utopian community, all of which they did. Bligh may also have treated them like total shit. He was set adrift on the Bounty's longboat with eighteen other men. (Later, he bitterly recalled how the mutineers “laughed at the helpless situation of the boat.”) Lacking a compass, and quite pissed, he and his crew of outcasts raged across the ocean, covering five thousand kilometers in forty-one days to disembark on the Dutch island of Timor, where they were rescued.

Two years later, undeterred, Bligh bivouacked to Tahiti, secured two thousand fresh saplings, and carried them without incident to Jamaica and St. Vincent. The fruit prospered, due in large part to native bats, whose rank poop spread breadfruit seed better than the gentle Caribbean breeze ever could. By 1797, the head of the St. Vincent Botanic Garden could write that “the breadfruit thrives (if possible) better than in its native soil.” The slaves, for their part, wanted nothing to do with any this botanical chest-thumping. They wouldn’t touch the stuff.

* * *

In time, others did. Today, breadfruit is culinary clay in the hands of a diaspora of chefs. Hawaiians call it ulu, Nigerians call it ukwa, Mexicans call it fruta de pan, and Papua New Guineans call it kapiak. Indians make breadfruit curry and breadfruit chips. Rastafarians make a “rundung” stew with breadfruit. Mexicans refry breadfruit the way they refry beans. In Trinidad, they make a breadfruit pumpkin soup. In Tobago, they love breadfruit pie. The Ministry of Agriculture in Kingston, Jamaica, has published recipes for breadfruit smoothies and deep-fried breadfruit croquettes on its website. The croquettes look particularly delicious.

Still, Americans have always kept their distance from the crop. Melville, for his part, liked how the tree looked. In Typee, he called it “a grand and towering object” comparable in stature to New England’s “patriarchal elm.” Its leaves were “cut and scalloped as fantastically as those of a lady’s lace collar.”

But its taste is a different thing. In 1913 all The Christian Science Monitor could offer was that the breadfruit was “palatable.” Over the century, public opinion downgraded the fruit from “palatable” to, as the Wall Street Journal recently put it, “all but inedible.” Epicurious, a popular cooking website, has recipes for “fruit bread” but not breadfruit. When a D.C.-based Smithsonian reporter was assigned to write about cooking with breadfruit, she came up empty. “You want fruit or bread?” the owner of an ethnic foods store asked her. If you consult WikiAnswers (and, really, don’t) about where to buy breadfruit, it says, “Not sure if they sell it in the U.S.” When I called my Whole Foods store in Austin to ask where I might find some breadfruit, the first word out of the produce guy’s mouth was “whoa!”

For a country that’s willing to eat just about anything anyone shoves down its national gullet, this is a curiously elusive relationship to have with a high-yielding fruit whose taste, palatable or not, is about as threatening as baby food. It’s hard to say why Americans shun breadfruit. Cole mentions that it “does not have a great shelf life.” Producers of animal feed—those who determine much of what’s grown and eaten in the United States (and elsewhere)—may be too addicted to the higher crude protein contents of corn and soy to explore the environmental benefits of breadfruit feed. And the breadfruit may also lack the potential to yield a ubiquitous byproduct—such as high-fructose corn syrup—to justify its mass production.

Fiji, ca. 1900-1930

But my hunch is that the American objection is primarily aesthetic. A picked breadfruit looks like a Nerf ball with a stick in it. When you bite into the flesh, there’s no juice. The fruit’s exterior resembles really bad acne. Neither Georgia O’Keefe nor any of the Dutch masters ever eroticized the breadfruit. The American palate is remarkably tolerant, but it has its standards: our food has to pack a flavorful punch, or evoke grandma’s kitchen, or at least display a modicum of healthful sex appeal. Breadfruit does none of the above.

That’s for the best, though. Consider the more common fruits and vegetables broadcast across the earth after European colonization. More often than not, their biodiversity has been hijacked by conventional agriculture, locked in a genetic straitjacket, and defended with poisons ranging from arsenic to DDT. Corn, bananas, wheat: to mass commercialize a crop is to create an army of cloned plants marching in lockstep against microscopic forces ready to level them in one fell swoop. Maybe it’s time for the Breadfruit Institute to stage its own mutiny and keep the breadfruit safe at home, secure in ancient tropical groves, feeding pigs and filling pies. We here on the mainland won’t miss a thing.

James McWilliams is a writer living in Austin, Texas. He teaches at Texas State University and is the author of Just Food: Where Locavores Get It Wrong And How We Can Truly Eat Responsibly .

The Thin Red Line

Wrong.

For many years, I had trouble spelling the word Wednesday. I remember writing out the days of the week in third grade and wrestling with the e’s: Wedenesday. Wedneseday. Wendsday. After all, were these spellings any less arbitrary than the correct one?

Even those of us who don’t think of ourselves as bad spellers have certain bugbears. Without the damning reminders of spell-check, I would still screw up interlocutor (I misspelled it, twice, while typing this), resistance, and accommodate. I probably shouldn’t beat myself up over the last; it’s number one on OxfordDictionary.com’s list of common misspellings. (Of course, which is on it, too.)

My mother strongly recalls an elementary-school spelling test in the late fifties. Committee was one of the words the class was told to spell. “I see three sets of twins on this committee,” hinted the teacher broadly. But my mom remembers the panic the hint induced; what did it mean? She managed to misspell it—but to this day, she remembers the incident and has never made the mistake again.

Sometimes it takes trauma for a lesson to sink in. Sometimes—see necessary, one of the few things I retained from middle-school Latin—we need to self-correct, remembering that this is a word that gives us regular trouble, and diligently apply a hard-won mnemonic. What interests me, though, are those words that we always get wrong, no matter how many times we see that red spell-check line, and look up the proper spelling, and castigate ourselves for the error.

It’s like a mental block. Or, maybe, an increasing reliance on technology; after all, a part of our brains knows we don’t really need to retain the knowledge. Maybe it’s a subconscious resistance (I just misspelled that, by the way—think of it with a French accent!) to the arbitrary strictures of language, and of Western society generally. (In this scenario, we are all storming a tiny, mental ivory tower—it is sort of like the Académie française, but full of really uptight elves.) Perhaps it’s a necessary means of preserving space in our memory cortex, or whatever. Or maybe we just like the reminder that, like children, we are always still learning. Or not learning, as the case may be. Wedenesday. Wedneseday. Wendsday. Wednesday.

When All You See Is Falling Blocks, and Other News

Is this, like, your reality, man? Photo: Aldo Gonzalez, via Wikimedia Commons

“Whence comes relatability? A hundred years ago, if someone said something was relatable, she meant that it could be told—the Shakespearean sense of relate—or that it could be connected to some other thing. As recently as a decade ago, even as relatable began to accrue its current meaning, the word remained uncommon. The contemporary meaning of relatable—to describe a character or a situation in which an ordinary person might see himself reflected—first was popularized by the television industry … But to reject any work because we feel that it does not reflect us in a shape that we can easily recognize—because it does not exempt us from the active exercise of imagination or the effortful summoning of empathy—is our own failure. It’s a failure that has been dispiritingly sanctioned by the rise of relatable.”

And for a certain audience, video games are all too relatable. They begin to impinge on reality, an occurrence that scientists call game transfer phenomena: “I used to play [Tetris] for hours every day. When I went to bed I would see falling blocks as I closed my eyes. I often experienced the same thing when waking up … a female video game player [was] suffering from delusions of being persecuted, exhibiting violent behavior and experiencing constant imaginary auditory hallucinations triggered by the music of the Super Mario Brothers video game.”

How do Hollywood studios create so much prop money for their movies without being detained as counterfeiters? (And why don’t we do the same?)

MFA vs. NYC = MFA vs. DMV. My personal favorite: the “Widening Gyre” road sign. New drivers always miss those.

The German film theorist Harun Farocki has died at seventy. His best-known work is probably The Inextinguishable Fire, from 1969: “In the film’s most famous moment, the camera dollies in on Farocki—who has just finished reading a napalm victim’s report out loud—as he puts out his cigarette on his arm, explaining that napalm burns at seven times the temperature.”

July 31, 2014

A Practical Handbook on the Distillation of Alcohol from Farm Products

It’s late, and you’re still awake. Allow us to help with Sleep Aid, a series devoted to curing insomnia with the dullest, most soporific prose available in the public domain. Tonight’s prescription: “Alcoholometry,” a chapter from A Practical Handbook on the Distillation of Alcohol from Farm Products, published in 1907.

David Rijckaert III, Man Sleeping, ca. 1649

Alcoholmetry is the name given to a variety of methods of determining the quantity of absolute alcohol contained in spirituous liquors. It will readily be seen that a quick and accurate method of making such determinations is of the very utmost importance to those who are engaged in the liquor traffic, since the value of spirit depends entirely upon the percentage of alcohol which it contains. When alcoholic liquors consist of simple mixtures of alcohol and water, the test is a simple one, the exact percentage being readily deducible from the specific gravity of the liquor, because to a definite specific gravity belongs a definite content of alcohol; this is obtained either by means of the specific gravity bottle, or of hydrometers of various kinds, specially constructed.

All hydrometers comprise essentially a graduated stem of uniform diameter, a bulb forming a float and a counterpoise or ballast. The hydrometers may either be provided with a scale indicated on the neck or else with weights added to sink the hydrometer to a certain mark. The first instruments are called hydrometers of “constant immersion,” the others, of “variable immersion.”

At the latter end of the last century, a series of arduous experiments were conducted by Sir C. Blagden, at the instance of the British government, with a view to establishing a fixed proportion between the specific gravity of spirituous liquors and the quantity of absolute alcohol contained in them. The result of these experiments, after being carefully verified, led to the construction of a series of tables, reference to which gives at once the percentage of alcohol for any given number of degrees registered by the hydrometer; these tables are invariably sold with the instrument. They are also constructed to show the number of degrees over-or under-proof, corresponding to the hydrometric degrees. Other tables are obtainable which give the specific gravity corresponding to these numbers.

The measurement of the percentage of absolute alcohol in spirituous liquors is almost invariably expressed in volume rather than weight, owing to the fact that such liquors are always sold by volume. Nevertheless, the tables referred to above show the percentage of spirit both by volume and weight.

In the United States the standard liquor, known as proof spirit, contains 92.3 per cent. by weight and 94.9 per cent. by volume, of absolute alcohol; it has a specific gravity of .9186 at 60° F. A proof gallon contains by measurement 100 parts of alcohol and 81.5 parts of water. The strength and therefore the value of spirituous liquors is estimated according to the quantity by volume of anhydrous spirit contained in the liquor with reference to this standard. Thus the expression “20 per cent. overproof,” “20 per cent. underproof,” means that the liquor contain 20 volumes of water for every 100 volumes over or under this fixed quantity, and that in order to reduce the spirit to proof, 20 per cent. of water by volume, must be subtracted or added, as the case may be. Any hydrometer constructed for the measurement of liquids of less density than water may be employed. That known as “Syke’s” is most commonly used for alcoholometric purposes. It is shown in Fig. 52 and consists of a spherical brass ball A, to which is fixed two stems; the upper one B is also of brass, flat, and about 3½ in. in length; it is divided into ten parts, each being subdivided into five, and the whole being numbered as shown in the figure. The lower stem C is conical, and slightly more than an inch long; it terminates in a weighted bulb D. A series of circular weights, of the form shown in the figure, accompany the instrument; these are slipped upon the top of the lower stem C, and allowed to slip down until they rest upon the bulb D. The instrument is used in the following way: It is submerged in the liquor to be tested until the whole of the upper stem is under the surface, and an idea is thus gained of the weight that will be required to partly submerge the stem. This weight is added, and the hydrometer again placed in the liquor. The figure on the scale to which the instrument has sunk when at rest is now observed, and added to the number on the weight used, the sum giving, by reference to the tables, the percentage by volume of absolute alcohol above or below the standard quantity.

In exact estimations, the temperature of the liquor tested must be carefully registered, and the necessary corrections made. In Jones’s hydrometer, which is an improvement upon Syke’s, a small spirit thermometer is attached to the bulb, and by noting the temperature of the liquor at the time of the experiment, and referring to the tables accompanying the instrument, the strength is found at once without the need of calculation.

Dica’s hydrometer is very similar to Jones’s instrument above described. It is of copper, has a stem fitted to receive brass poises, a thermometer, a graduated scale, etc.

In Europe, Gay-Lussac’s hydrometer and tables are chiefly used for alcoholometric testing. This instrument is precisely similar in construction to those of Twaddle and Baume. On the scale, zero is obtained by placing it in pure distilled water at 59° F., and the highest mark, or 100, by placing it in pure alcohol at the same temperature, the intermediate space being divided into 100 equal divisions, each representing one per cent. of absolute alcohol. The correction for temperature, as in the above cases, is included in the reference tables.

Another hydrometer, used in France for alcoholometric determinations, is Cartier’s. In form it is precisely similar to Baume’s hydrometer. Zero is the same in both instruments, but the point marked 30° in Cartier’s is marked 32° in Baume’s, the degrees of the latter being thus diminished in the proportion of 15 or 16. Cartier’s hydrometer is only used for liquids lighter than water.

The alcoholmeter of Tralles is the official instrument for testing alcoholic liquors in the U. S. but the instrument which is most generally used both here and abroad is that of Beaumé. There are two instruments bearing Beaumé’s name, one for liquids lighter than water, the other for those which are heavier. All hydrometers, alcoholmeters and saccharometers work on the same principle, though they are each differently graduated for the particular work to be done and the details of the measuring process are slightly different. All these instruments are provided with tables whereby their readings may be corrected and the specific gravity of the liquid determined.

The above hydrometric methods can be safely employed only when the spirit tested contains a very small amount of solid matter, since, when such matter is contained in the liquor in quantity, the density alone cannot possibly afford a correct indication of its richness in alcohol. Many methods have been proposed for the estimation of alcohol in liquor, containing saccharine coloring and extractive matters, either in solution or suspension. Undoubtedly the most accurate of these, though at the same time the most tedious, is to subject the liquor to a process of distillation by which a mixture of pure alcohol and water is obtained as the distillate. This mixture is carefully tested with the hydrometer, and the percentage of alcohol in it determined by reference to the tables as above described; from this quantity and the volume of the original liquor employed the percentage by volume of alcohol in that liquor is readily found. The condensing arrangement must be kept perfectly cool, if possible in a refrigerator, as the alcohol in the distillate is very liable to be lost by re-evaporation. When great accuracy is desired, and time is at the operator’s disposal, the above method is preferable to all others.

It is performed in the following manner: Three hundred parts of the liquor to be examined are placed in a small still, or retort, and exactly one-third of this quantity is distilled over. A graduated glass tube is used as the receiver, in order that the correct volume may be drawn over without error. The alcoholic richness of the distillate is then determined by any of the above methods, and the result is divided by three, which gives at once the percentage of alcohol in the original liquor. The strength at proof may be calculated from this in the ordinary way.

If the liquor be acid, it must be neutralized with carbonate of soda before being submitted to distillation. From eight to ten per cent. of common salt must be added, in order to raise the boiling point, so that the whole of the spirit may pass over before it has reached the required measure. In the case of the stronger wines it is advisable to distil over 150 parts and divide by two instead of three. If the liquor be stronger than 25 per cent. by volume of alcohol, or above 52 to 54 percent. under-proof, an equal volume of water should be added to the liquid in the still, and a quantity distilled over equal to that of the sample tested, when the alcoholic strength of the distillate gives, without calculation, the correct strength required. If the liquor be stronger than 48 to 50 per cent. under-proof, three times its volume of water must be added, and the process must be continued until the volume of the distillate is twice that of the sample originally taken. In each case the proportionate quantity of common salt must be added.

For the estimation of alcohol in wines, liquors, etc., the following method may be employed: A measuring flask is filled up to a mark on its neck with the liquor under examination, which is then transferred to a retort; the flask must be carefully rinsed out with distilled water, and the rinsings added to the liquor in the retort. About two-thirds are then drawn over into the same measuring flask, and made up to its previous bulk with distilled water, at the same temperature as that of the sample before distillation. The strength is then determined by means of Syke’s hydrometer, and this, if under-proof, deducted from 100, gives the true percentage of proof-spirit in the wine.

A quick, if not always very exact, method consists in determining the point at which the liquor boils. The boiling point of absolute alcohol being once determined, it is obvious that the more it is diluted with water the nearer will the boiling point of the mixture approach that of water; moreover, it has been proved that the presence of saccharine and other solid matters has but an almost inappreciable effect upon this point. Field’s alcoholometer, since improved by Ure, is based upon this principle. It is shown in Fig. 53, and consists, roughly speaking, of a cylindrical vessel A, to contain the spirit; this vessel is heated from beneath by a spirit lamp, which fits into the case B. A delicate thermometer C, the bulb of which is introduced into the spirit, is attached to a scale divided into 100 divisions, of which each represents one degree over-or under-proof. This method is liable to several small sources of error, but when a great many determinations have to be made, and speed is an object rather than extreme accuracy, this instrument becomes exceedingly useful. It does not answer well with spirits above proof, because the variation in their boiling points are so slight as not to be easily observed with accuracy. But for liquors under-proof, and especially for wines, beer, and other fermented liquors, it gives results closely approximating to those obtained by distillation, and quite accurate enough for all ordinary purposes. Strong liquors should therefore be tested with twice their bulk, and commercial spirits with an equal bulk, of water, the result obtained being multiplied by two or three, as the case may be.

Another very expeditious, but somewhat rough, method was invented by Geisler. It consists in measuring the tension of the vapor of the spirit, by causing it to raise a column of mercury in a closed tube. The very simple apparatus is shown in Fig. 54. A is a small glass bulb, fitted with a narrow tube and stop-cock. This vessel is completely filled with the spirit, and is then screwed upon a long, narrow tube B, bent at one end and containing mercury. This tube is attached to a graduated scale showing the percentage of absolute alcohol above or below proof. To make the test the cock is opened, and the bulb, together with the lower part of the tube, is immersed in boiling water, which gradually raises the spirit to its boiling-point. When this is reached, the vapor forces the mercury up the tube, and, when stationary, the degree on the scale to which it has ascended gives directly the percentage of alcohol.

Another method, which is not to be relied on for very weak liquors, but which answers well for cordials, wines, and strong ales, is that known as Brande’s method. The liquor is poured into a long, narrow glass tube, graduated centesimally, until it is half-filled. About 12 or 15 per cent. of subacetate of lead, or finely powdered litharge, is then added, and the whole is shaken until all the color is destroyed. Powdered anhydrous carbonate of potash is next added until it sinks undissolved in the tube, even after prolonged agitation. The tube is then allowed to rest, when the alcohol is observed to float upon the surface of the water in a well-defined layer. The quantity read off on the scale of the tube and doubled, gives the percentage by volume of alcohol in the original liquid. The whole operation may be performed in about five minutes, and furnishes reliable approximative results. In many cases it is necessary to add the lead salt for the purpose of decolorizing the liquid.

For the investigation of the amount of sugar in, or the concentration of the mash, or beer, a specially scaled hydrometer is used which is termed a saccharometer. Sugar possesses a higher degree of specific gravity than water, and hence it follows that the greater the amount of sugar in the mash the higher will be the specific gravity. The less the hydrometer sinks into the fluid the greater the amount of sugar present. Saccharometers are provided with thermometers whereby the reading may be corrected to a standard temperature, usually 59° F. The saccharometer is correct for solutions containing sugar alone but it is only approximately correct for mash liquor which contains a variety of other matters in variable quantities.

It is a prime necessity that the distiller should be able to determine if the mash has been completely saccharified by the malt. For this purpose a solution of iodine is used. Iodine gives to starch a blue color. If the starch however, has been completely changed into sugar there will either be no discoloration or the filtered mash liquid which is at first a yellowish red becomes blue, then violet, and at last red.

Still awake? Read more here.

Sound Off

The Cincinnati Public Library Card Catalog. Image via Retronaut

The other day, a friend sent me a link to a Reddit conversation: What common sounds from a hundred years ago are very rare or just plain don’t exist anymore?

This, in turn, led us to the Museum of Endangered Sounds, which I highly recommend to anyone with a pair of headphones and a few hours to kill. Of course, we can’t even document some of them—the early-morning scuttle of coal, for instance, was probably too humble ever to rate a recording. I mean, how many of us have bothered to record the hiss of a radiator—and presumably that won’t be around forever. For that matter, someone ought to memorialize the rattle of a dead, incandescent bulb.

I must have had this in mind when I ran across this image on Retronaut. Because the sound of a card catalog—the squeak of the drawer, the slight ruffle of the stiff paper, the sliding noise as a card is pulled from the file—is almost certainly on the endangered list. (To say nothing of everything else in the picture.)

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers