The Paris Review's Blog, page 673

August 14, 2014

Beach Read

Image via Urban75.org

Over at the LRB blog, Peter Pomerantsev has an affecting story about love, lies, and hair in Brighton Beach—you know,

the Russian ghetto where Brooklyn meets the ocean, a last stop on the subway from Manhattan. In the evening the boardwalk would be full of Russian immigrants with gaudy haircuts and fur-wrap finery, and as the light faded you could forget you were in America.

He tells of a time in 1982—and this is a true story—when an unemployed electrician named Lev found himself spinning a web of lies in pursuit of a beautiful young woman. What captivated him was her alluring, progressive hairdo: “shaved at the back with a Siouxsie Sioux spiked mop on top. He couldn’t stop staring at it.” Lev told the woman he was an intellectual, a Soviet dissident—he wasn’t. He said he was single—he was married, with kids. He said he’d been arrested by the KGB—he hadn’t been.

The story takes a tragicomic turn in the end that I won’t spoil here, except to say that it involves the woman’s haircut and has a singularly arresting image of a stroll on the Brighton Beach boardwalk. Read it here.

Those with no tolerance for shameless plugs can stop reading now, because I’m only about to mention our subscription deal with the LRB, which is, like this story, a kind of summer romance, and is, unlike this story, not sad in the slightest. Subscribe now and you’ll save on both magazines.

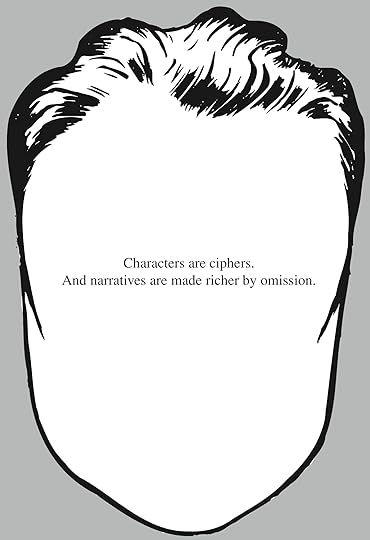

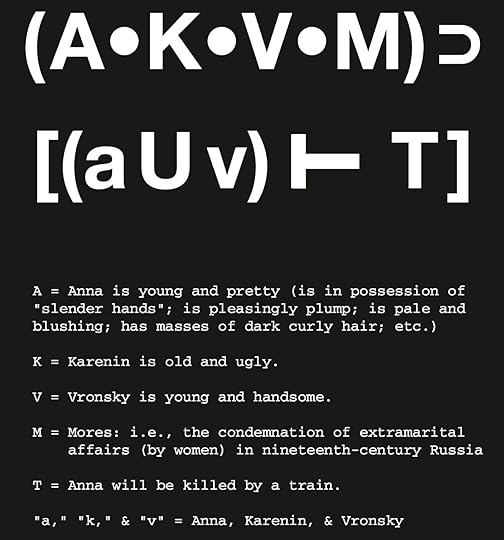

What We See When We Read

If I said to you, “Describe Anna Karenina,” perhaps you’d mention her beauty. If you were reading closely you’d mention her “thick lashes,” her weight, or maybe even her little downy mustache (yes—it’s there). Matthew Arnold remarks upon “Anna’s shoulders, and masses of hair, and half-shut eyes … ”

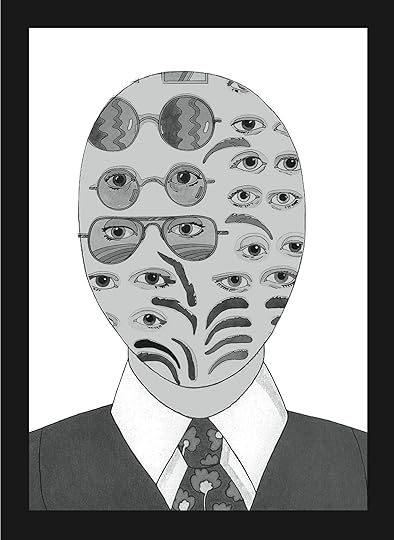

But what does Anna Karenina look like? You may feel intimately acquainted with a character (people like to say, of a brilliantly described character, It’s like I know her), but this doesn’t mean you are actually picturing a person. Nothing so fixed—nothing so choate.

Most authors (wittingly, unwittingly) provide their fictional characters with more behavioral than physical description. Even if an author excels at physical description, we are left with shambling concoctions of stray body parts and random detail (authors can’t tell us everything). We fill in gaps. We shade them in. We gloss over them. We elide. Anna: her hair, her weight—these are only facets, and do not make up a true image of a person. They make up a body type, a hair color … What does Anna look like? We don’t know—our mental sketches of characters are worse than police composites.

Visualizing seems to require will …

… though at times it may also seem as though an image of a sort appears to us unbidden.

(It is tenuous, and withdraws shyly upon scrutiny.)

I canvass readers. I ask them if they can clearly imagine their favorite characters. To these readers, a beloved character is, to borrow William Shakespeare’s phrase, “bodied forth.”

These readers contend that the success of a work of fiction hinges on the putative authenticity of the characters. Some readers go further and suggest that the only way they can enjoy a novel is if the main characters are easily visible:

“Can you picture, in your mind, what Anna Karenina looks like?” I ask.

“Yes,” they say, “as if she were standing here in front of me.”

“What does her nose look like?”

“I hadn’t thought it out; but now that I think of it, she would be the kind of person who would have a nose like … ”

“But wait—How did you picture her before I asked? Noseless?”

“Well … ”

“Does she have a heavy brow? Bangs? Where does she hold her weight? Does she slouch? Does she have laugh lines?”

(Only a very tedious writer would tell you this much about a character. Though Tolstoy never tires of mentioning Anna’s slender hands. What does this emblematic description signify for Tolstoy?)

Some readers swear they can picture these characters perfectly, but only while they are reading. I doubt this, but I wonder now if our images of characters are vague because our visual memories are vague in general.

* * *

A thought experiment: Picture your mother. Now picture your favorite literary character. (Or: Picture your home. Then picture Howards End.) The difference between your mother’s afterimage and that of a literary character you love is that the more you concentrate, the more your mother might come into focus. A character will not reveal herself so easily. (The closer you look, the farther away she gets.)

(Actually, this is a relief. When I impose a face on a fictional character, the effect isn’t one of recognition, but dissonance. I end up imagining someone I know.* And then I think, That isn’t Anna!)

*I recently had the experience while reading a novel wherein I thought I had clearly seen a character—a society woman with “widely spaced eyes.” When I subsequently scrutinized my imagination, I discovered that what I had been imagining was the face of one of my coworkers, grafted onto the body of an elderly friend of my grandmother’s. When brought into focus, this was not a pleasant sight.

*I recently had the experience while reading a novel wherein I thought I had clearly seen a character—a society woman with “widely spaced eyes.” When I subsequently scrutinized my imagination, I discovered that what I had been imagining was the face of one of my coworkers, grafted onto the body of an elderly friend of my grandmother’s. When brought into focus, this was not a pleasant sight.

Often, when I ask someone to describe the physical appearance of a key character from their favorite book they will tell me how this character moves through space. (Much of what takes place in fiction is choreographic.)

One reader told me Benjy Compson from William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury was “lumbering, uncoordinated … ”

But what does he look like?

Literary characters are physically vague—they have only a few features, and these features hardly seem to matter—or, rather, these features matter only in that they help to refine a character’s meaning. Character description is a kind of circumscription. A character’s features help to delineate their boundaries—but these features don’t help us truly picture a person.*

* * *

It is precisely what the text does not elucidate that becomes an invitation to our imaginations. So I ask myself: Is it that we imagine the most, or the most vividly, when an author is at his most elliptical or withholding?

(In music, notes and chords define ideas, but so do rests.)

*Or is it that comprehensiveness is not an important factor in the identification of anything?

William Gass, on Mr. Cashmore from Henry James’s The Awkward Age:

We can imagine any number of other sentences about Mr. Cashmore added … now the question is: what is Mr. Cashmore? Here is the answer I shall give: Mr. Cashmore is (1) a noise, (2) a proper name, (3) a complex system of ideas, (4) a controlling perception, (5) an instrument of verbal organization, (6) a pretended mode of referring, and (7) a source of verbal energy.

The same could be said of any character—of Nanda, from the same book, or of Anna Karenina. Of course—isn’t the fact that Anna is ineluctably drawn to Vronsky (and feels trapped in her marriage) more significant than the mere morphological fact of her being, say, “full-figured”?

It is how characters behave, in relation to everyone and everything in their fictional, delineated world, that ultimately matters. (“Lumbering, uncoordinated …”)

Though we may think of characters as visible, they are more like a set of rules that determines a particular outcome. A character’s physical attributes may be ornamental, but their features can also contribute to their meaning.

(What is the difference between seeing and understanding?)

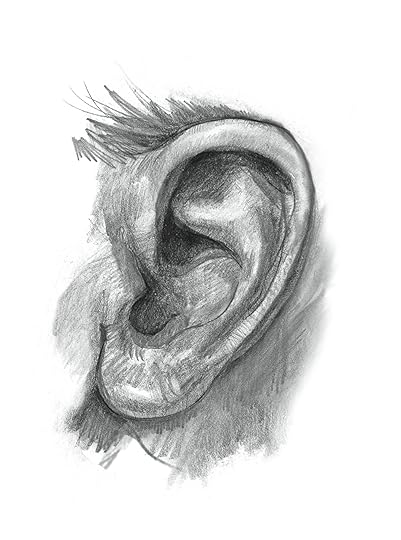

Take Karenin’s ears … (Karenin is the cuckolded husband of Anna Karenina.) Are his ears large or small?

At Petersburg, so soon as the train stopped and she got out, the first person that attracted her attention was her husband. ‘Oh, mercy! Why do his ears look like that?’ she thought, looking at his frigid and imposing figure, and especially the ears that struck her at the moment as propping up the brim of his round hat …

Karenin’s ears grow in proportion to his wife’s disaffection with him. In this way, these ears tell us nothing about how Karenin looks, and a great deal about how Anna feels.

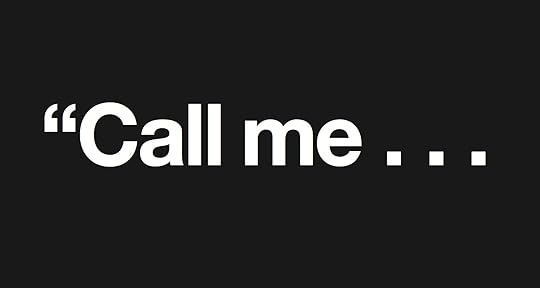

Ishmael.” What happens when you read the first line of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick?

You are being addressed, but by whom? Chances are you hear the line (in your mind’s ear) before you picture the speaker. I can hear Ishmael’s words more clearly than I can see his face. (Audition requires different neurological processes than vision, or smell. And I would suggest that we hear more than we see while we are reading.)

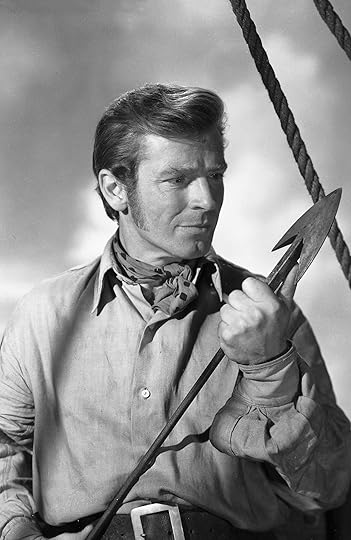

If you did manage to summon an image of Ishmael, what did you come up with? A seafaring man of some sort? (Is this a picture or a category?) Do you picture Richard Basehart, the actor in the John Huston adaptation?

(One should watch a film adaptation of a favorite book only after considering, very carefully, the fact that the casting of the film may very well become the permanent casting of the book in one’s mind. This is a very real hazard.)

* * *

What color is your Ishmael’s hair? Is it curly or straight? Is he taller than you? If you don’t picture him clearly, do you merely set aside a chit, a placeholder that says, “Protagonist, narrator—first person”? Maybe this is enough. Ishmael probably evokes a feeling in you—but this is not the same as seeing him.

Maybe Melville had a specific image in mind for his Ishmael. Maybe Ishmael looked like someone he knew from his years at sea. But Melville’s image is not ours. And no matter how well illustrated Ishmael may or may not be (I can’t remember if Melville describes Ishmael’s physical attributes, and I’ve read the book three times), chances are we will have to constantly revise our image of him as the book progresses. We are ever reviewing and reconsidering our mental portraits of characters in novels: amending them, backtracking to check on them, updating them when new information arises …

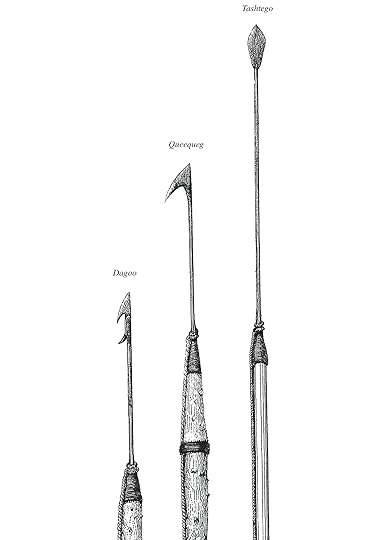

What kind of face you assign to Ishmael might depend upon what mood you are in on a particular day. Ishmael might look as different from one chapter to the next as, say, Tashtego does from Stubb.

Sometimes, in a play, several actors perform a single role. In these instances, the cognitive dissonance aroused by multiple actors is evident to the theatrical audience. But after reading a novel, we think back on its characters as if they were played by single actors. (In a narrative, multiplicity of “character” is read as psychological complexity.)

Another question: As a character develops throughout the course of a novel, does the way this character “looks” to you (their appearance) change … as a result of their inner development? (A real person may become more beautiful to us once we are better acquainted with their nature—and in these cases our increased affection isn’t due to some closer physical observation.)

Are characters complete as soon as they are introduced? Perhaps they are complete, but just out of order; the way a puzzle might be.

Levin gazed at the portrait, which stood out from the frame in the brilliant light thrown on it, and he could not tear himself away from it … It was not a picture, but a living, charming woman, with black curling hair, with bare arms and shoulders, with a pensive smile on the lips, covered with soft down; triumphantly and softly she looked at him with eyes that baffled him. She was not living only because she was more beautiful than a living woman can be.

—Anna Karenina

Peter Mendelsund is the associate art director of Alfred A. Knopf and a recovering classical pianist. His designs have been described by The Wall Street Journal as being “the most instantly recognizable and iconic book covers in contemporary fiction.” He lives in New York.

This is an excerpt from What We See When We Read , by Peter Mendelsund. Copyright © 2014 by Peter Mendelsund. With permission of the publisher, Vintage Books. All rights reserved.

Fit to Print

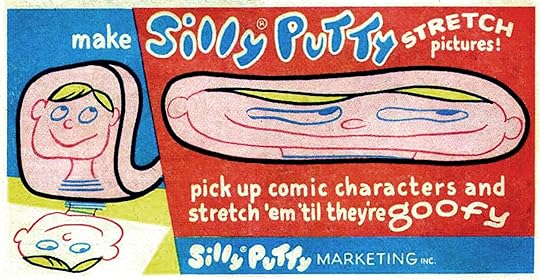

A 1965 ad for Silly Putty, plainly advertising its ability to pick up newsprint.

On Monday, the Times’s David Carr had a gloomy prognosis for the fate of print newspapers. He wrote,

It’s a measure of the basic problem that many people haven’t cared or noticed as their hometown newspapers have reduced staffing, days of circulation, delivery and coverage. Will they notice or care when those newspapers go away altogether? I’m not optimistic about that.

Carr and many others are alive to the societal, artistic, and human implications of this loss. All this aside, it means lost jobs. You don’t need me to say that, or to belabor the passing of an era. These things are too huge to contemplate.

So you start thinking about the stupid things. The oblong bags newspapers come in. What will people use to clean up after their dogs? Where will they get rubber bands? Will “train-style” folding become a lost art? And what about Silly Putty?

Silly Putty can’t really be called a major casualty in this overhaul, but it is something that will be decisively rendered extinct. It’s a retro toy now—if you can even call something which was so obviously the byproduct of industrial experimentation a “toy”—but with the death of the newspaper, one of its primary functions (if you can call it a function) will be nullified.

Silly Putty should be placed in a time capsule immediately on grounds of sheer weirdness. Try explaining it to an alien: “It’s putty, but it’s … silly. It’s sort of flesh-colored. It has a really distinctive chemical smell. It stretches, and snaps, and turns into a puddle. If you roll it up, it bounces like a ball. Oh, and it picks up newsprint. Then it gets really grubby and you keep it in a plastic egg, forever.” If Silly Putty’s origins are clear enough—it was a World War II–era attempt to address rubber shortages—its ability to transfer newsprint is more mysterious. How did someone figure this out? And how did anyone decide it was a selling point?

And yet, from the get-go, it was. When this sea captain (you just have to stop asking after a certain point) extolls its manifold virtues in an early commercial, newsprint-transfer is listed prominently:

In fact, it’s been a while since Silly Putty was really able to copy newsprint well: it worked only on petroleum-based inks, and in recent years, inks have increasingly been made from soy products. Nevertheless, today I purchased an egg, my first. (I don’t mean the first I’ve owned; Silly Putty was one of those things that just sort of … materialized. It’s not what any kid would request, or spend his own money on.)

It’s true: When I pressed it to Page Six, I could barely make out the name “Antonio Banderas”—and that was boldface! When I folded the mirror image back into the Silly Putty, it showed barely the faintest smudge of gray.

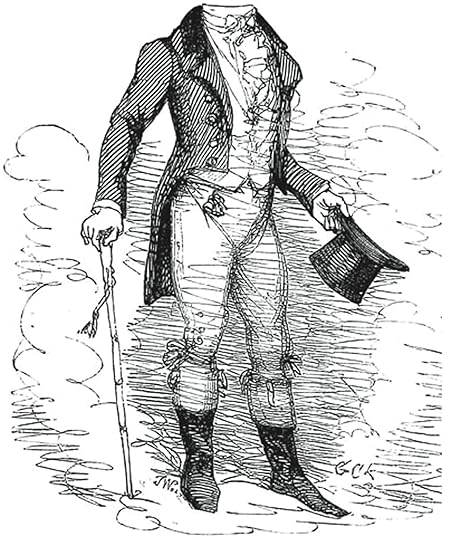

James Berry, Celebrity Executioner

James Berry

From “Hanging: From a Business Point of View,” a chapter in James Berry’s My Experiences as an Executioner (1892). Berry was a renowned hangman in England from 1884 to 1891; he refined the “long drop” method pioneered by William Marwood, and once famously failed to execute John Babbacombe Lee, “The Man They Couldn’t Hang,” when the scaffold’s trap door repeatedly stuck.

I am not ashamed of my calling, because I consider that if it is right for men to be executed (which I believe it is, in murder cases) it is right that the office of executioner should be held respectable. Therefore, I look at hanging from a business point of view.

When I first took up the work … I made application on a regular printed form, which gave the terms and left no opening for mistake or misunderstanding … I still use this circular when a sheriff from whom I have had no previous commission writes for terms. The travelling expenses are understood to include second-class railway fare from Bradford to the place of execution and back, and cab fare from railway station to gaol. If I am not lodged in the gaol, hotel expenses are also allowed.

There are, on an average, some twenty executions annually, so that the reader can calculate pretty nearly what is my remuneration for a work which carries with it a great deal of popular odium, which is in many ways disagreeable, and which may be accompanied, as it has been in my own experience, by serious danger, resulting in permanent bodily injury …

I always try to remain unknown while travelling, but there is a certain class of people who will always crowd round as if an executioner were a peep-show … I got into a carriage with a benevolent-looking old gentleman. A little crowd collected round the door, and just as we were starting a porter stuck his head into the window, pointed to my fellow-passenger, and with a silly attempt at jocularity said:—“I hope you’ll give him the right tightener.” The old gentleman seemed much mystified, and of course I was quite unable to imagine what it meant. At Darlington there was another little crowd, which collected for a short time about our carriage. Fortunately none of the people knew me, so that when the old gentleman asked them what was the matter they could only tell him that Berry was travelling by that train and that they wanted to have a look at him. The old gentleman seemed anxious to see such an awful man as the executioner, and asked me if I should know him if I saw him. I pointed out a low-looking character as being possibly the man, and my fellow-traveller said, “Yes! very much like him.” I suppose he had seen a so-called portrait of me in one of the newspapers. We got quite friendly, and when we reached Durham, where I was getting out, he asked for my card. The reader can imagine his surprise when I handed it to him.

Red Pens for Robots, and Other News

Better wielded by machines. Photo: ellenm1, via Flickr

Residents of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, rise up, and reclaim Gilbert Sorrentino as your bard! “Sorrentino died of lung cancer in Brooklyn in 2006; he remains widely uncelebrated in his own neighborhood, his own borough, despite the fact that so many of his books are set there, and he lived so much of his life there. The Fort Hamilton High School Alumni Association doesn’t list him in its Hall of Fame. The libraries don’t stock his books, and neither does the local bookstore. I spent thirty years in Bay Ridge as a bookish neighborhood enthusiast without ever hearing his name, until a poet mentioned it to me in passing.”

Where do typos come from? Our foolish brains, and their inveterate laziness. There’s no escaping it, really.

Which is part of why we need editors—but even editors aren’t good enough. What the world needs, apparently, is robot editors: “Students almost universally resist going back over material they’ve written … [but they] are willing to revise their essays, even multiple times, when their work is being reviewed by a computer and not by a human teacher. They end up writing nearly three times as many words … Students who feel that handing in successive drafts to an instructor wielding a red pen is ‘corrective, even punitive’ do not seem to feel rebuked by similar feedback from a computer.”

“It’s a common and easy enough distinction, this separation of books into those we read because we want to and those we read because we have to, and it serves as a useful marketing trope for publishers, especially when they are trying to get readers to take this book rather than that one to the beach. But it’s a flawed and pernicious division … There are pleasures to be had from books beyond being lightly entertained. There is the pleasure of being challenged; the pleasure of feeling one’s range and capacities expanding; the pleasure of entering into an unfamiliar world, and being led into empathy with a consciousness very different from one’s own … ”

Exploring the annals of Dalkey Archive Press, which is now thirty years old.

August 13, 2014

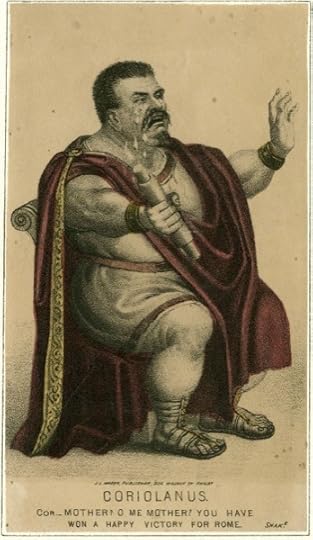

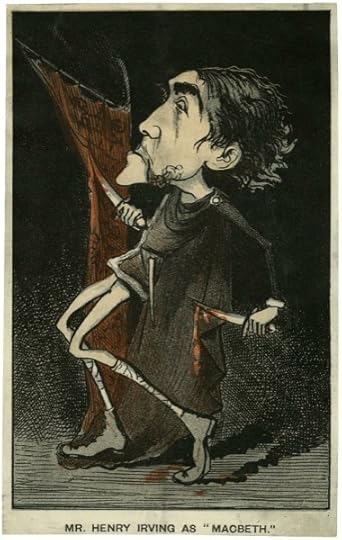

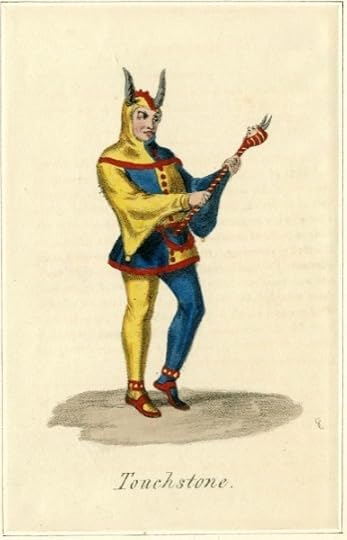

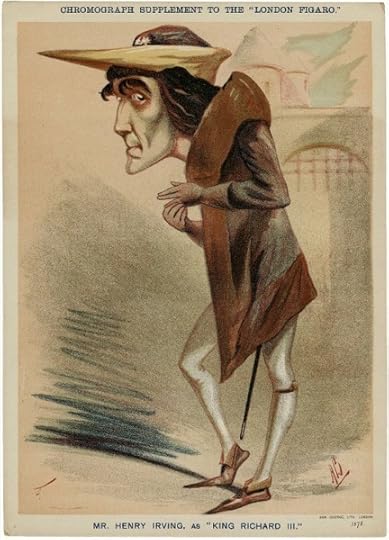

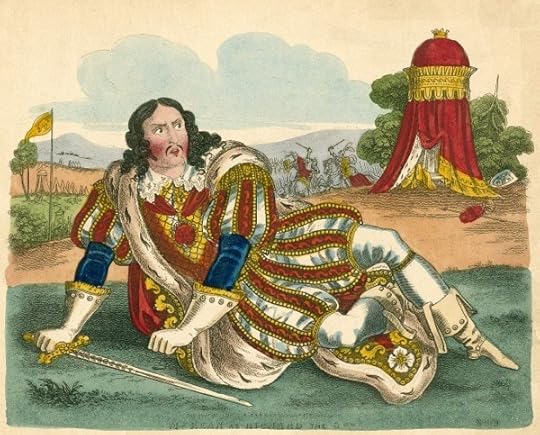

Corpulent Coriolanus

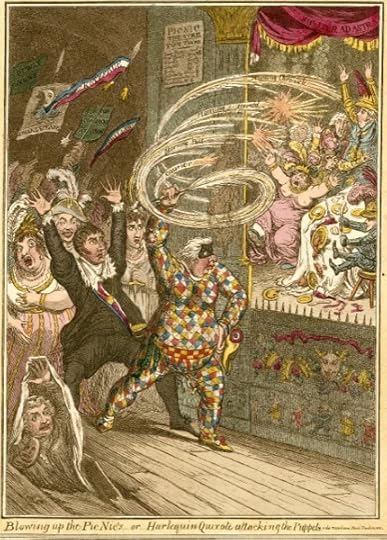

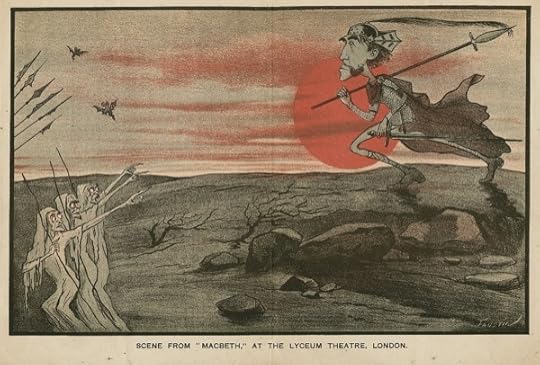

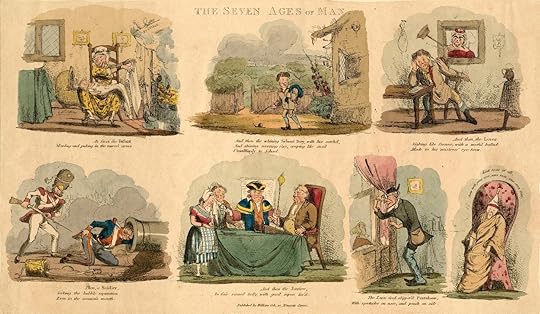

Yesterday the Folger Shakespeare library released some eighty thousand images into the Creative Commons, a deluge of bardic miscellany from which the Internet may well never recover. There are astrology charts, game boards, hornbooks, advertisements, illustrations, engravings, and more, all of it related, however tangentially, to Shakespeare. We’ve had TPR interns taking a fine-tooth comb to the collection for twenty-four hours now, with closely monitored breaks for water and gruel, and we present to you now the results of their exhaustive research. There’s a plump Coriolanus with a salty cheek; a lurid and seemingly shrunken Lady Macbeth; a King Lear who seems to have wandered off the Grateful Dead tour bus; and a plus-sized “Harlequin Quixote,” dressed in a modish, dance-floor-ready romper, attacking some puppets.

There is, perhaps best of all, this illustrated version of Shakespeare’s “Seven Ages of Man” monologue, from Jaques in As You Like It. Click to enlarge:

Oh, to be a lean and slippered pantaloon...

Memoirs

Lauren Bacall and Howard Hawks, ca. 1943

When I heard the news that Lauren Bacall had died, at first I felt the melancholy we all feel when another legend of a fading age goes. And then I thought: Is she in the Scotty Bowers book?

Since Valentine’s Day, 2012, the world has been divided unevenly between those who still live in a state of blissful innocence, and those who have read Scotty Bowers’s memoir, Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars. If you enjoy old movies, mourn the passing of the Golden Age of Hollywood, want to be able to watch Mutiny on the Bounty, or have a soul, I beg you not to open this book, for once you do, you’ll feel compelled to devour every page in fascinated horror. Everyone else: read it immediately.

My mom was the first one I knew to read the book. She spoke so darkly and incessantly about it that I felt compelled to buy it. (This was one of the few cases in which I felt an e-book was the appropriate medium.) After reading it, obsessively, I started evangelizing myself, much as my mom had, in the vaguest and most menacing terms. I wanted people to know—and yet, I didn’t. I felt like a sort of Ancient Mariner, wandering the world and sharing the darkness I had seen.

Not that the book is especially dark, mind you. Scotty Bowers is possibly the happiest man to have ever walked the earth. Here is the rather sanitized Wikipedia description:

Bowers fought in the Pacific, including at the Battle of Iwo Jima, as a paramarine in the Marine Corps during World War II. In 1946, he was pumping gas at a service station when he says Walter Pidgeon gave him $20 for a gay sexual encounter. Word spread about Bowers among Pidgeon’s friends, and Bowers turned the service station into a meeting place for paid sexual encounters, which took place in a nearby trailer or hotel, with his old marine friends assisting him in the business. In 1950, he stopped working at the service station and began a legitimate business as a party bartender, which also became well known in Hollywood for Bowers arranging sexual encounters for gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, and heterosexuals. In the book, Bowers claims he arranged gay or bisexual encounters for Cary Grant and his longtime lover Randolph Scott, George Cukor, and Rock Hudson, as well as for actresses Vivien Leigh and Katharine Hepburn, for whom Bowers claims to have arranged encounters with “over 150 different women.” He claims to have arranged various types of encounters for Desi Arnaz, Alfred A. Knopf, Sr., Spencer Tracy, Cole Porter, Laurence Olivier, Tyrone Power, Tennessee Williams, Howard Hughes, Charles Laughton, John Carradine, Montgomery Clift, Anthony Perkins and his longtime lover Tab Hunter, Malcolm Forbes, Harold Lloyd, Tony Richardson, Errol Flynn, Bob Hope, W. Somerset Maugham, Vincent Price, Édith Piaf, J. Edgar Hoover—who he says was a cross-dresser—Brian Epstein, Raymond Burr, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor (both of whom Bowers claims were homosexual; he claims that their marriage was a sham). Grove Press had the book reviewed by a libel lawyer prior to publication. Bowers’s illicit activities were never caught by authorities; he kept all his contact information in his head. Bowers claims to have personally had multiple gay sex encounters with Spencer Tracy. He also claims that the romance between Tracy and Hepburn was a myth dreamed up by publicists to give each a facade of heterosexuality, although both (according to Bowers) were homosexual. The veracity of Bowers’s many claims has been endorsed by Gore Vidal.

Bowers put a stop to this aspect of his life and business when the AIDS epidemic began, though he continued to work as a handyman and bartender during this time. He got married in 1984 to his wife, Lois. Bowers claims he never took payment for arranging sexual encounters for others, only when he provided sex himself, and that though he is bisexual, his own preference is for women. Bowers never talked about these experiences before but decided to do so now because most of the people involved are now dead and can no longer be affected by his revelations.

(If you want a far franker, more thorough—and more illuminating—description—read this. NSFW, I guess.)

By the end of the book, you’ll be changed. Yes, you’ll know a lot of stuff about peoples’ sex lives, but somehow, you’ll feel broadened and jaded yourself; sex will have been stripped of mystique, effort, morality, beauty. This is either a beautiful or terrifying thing. It is certainly philosophically powerful.

Anyway, I had a vague idea that Lauren Bacall had cameo’d in the book—almost everyone does—but when I quickly ran a search (another reason it’s a good idea to read this one electronically; you’ll want to be able to reference it easily), I came up with nothing.

Instead, I turned to my other old Hollywood oracle: David Niven, whose memoirs of Hollywood, Bring on the Empty Horses and The Moon’s a Balloon, are compulsory reading—and not just for the soulless. Urbane, kind, and funny, Niven is a terrific raconteur, and somehow his assertions feel completely reliable. And as I thought, he had plenty to say about Bacall. Indeed, his words make a pretty terrific epitaph: “ ‘Betty’ Bacall was the perfect mate for Bogey—beautiful, fair, warm, talented and highly intelligent. She gave as good as she got in the strong personality department. Women and men love her with equal devotion.”

His Own Wavelength

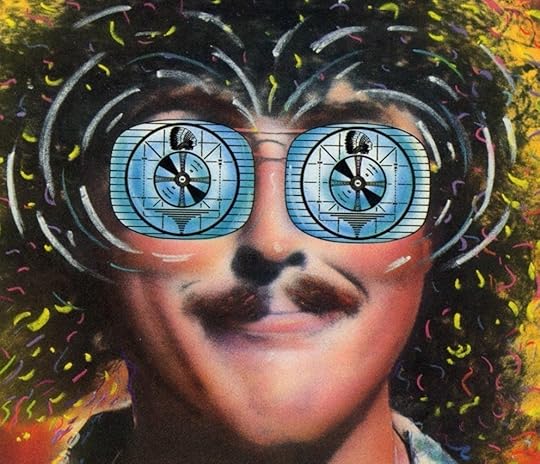

Talking to Weird Al about his process.

From the promotional poster for UHF, Al’s 1989 film.

It’s not that there wasn’t a self-referential pop culture before “Weird Al” Yankovic; it’s just that those of us under forty might have a hard time remembering it. Just as difficult to imagine are those who, even after all these years—after all the albums and songs and verses, after all the puns and parodies and poetry—still think of Weird Al as nobody more than that guy who rhymes about food over popular music. Weird Al engages the entire culture, in all its functions and facets, through his lyrics, his videos, his original musical-style parodies. Just how he does it all remains a mystery no matter how often he explains it.

When he explained it to me recently, by Skype, he said much that I’d never heard before, even though, like most culture vultures my age, I’ve followed his career since the early eighties. And if a lot of those early songs did in fact find their rhymes in the names of food, it’s also true that a lot of them did not. His songs have become more intricate with each new album, even as they’ve become more expansive. And more popular, too. It’s easy to forget that Weird Al’s career, after an early but tough start, nearly failed to make it very far out of the eighties. It wasn’t until his parody of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” (“Smells Like Nirvana”) that he safely established full traction and momentum.

That was 1992. Since then, his career has been an inverted, warped variation on the typical pop-music career, just as his songs have always been inverted, warped variations on typical pop music. In 2006, he released his first album ever to break the top ten (Straight Outta Lynwood, featuring “White & Nerdy”). And now, eight years after that, and thirty-five years after his very first single—“My Bologna,” which, yeah, is about food—his new album, Mandatory Fun, has gone number one. It’s not just the first time Weird Al’s done it; it’s the first time any comedian’s done it since Allan Sherman, with My Son, the Nut in 1963.

Which makes a special kind of sense, because the song parodies of Allan Sherman did a lot to put Al on the road to where he is now. “Allan Sherman is one of my all-time heroes,” he said. “I would say my Mount Rushmore of inspiration would be Allan Sherman, Stan Freberg, Spike Jones, and Tom Lehrer. Those are probably the four main people that influenced me and inspired me, and I was exposed to them through the Dr. Demento Show,” that ageless, perpetually hospitable home to musical satire.

By the time he was out of high school—he graduated at the age of sixteen as class valedictorian—his homemade parodies were being played on Demento’s radio show. While studying architecture at Cal Polytechnic, he worked at the campus radio station and continued contributing to Demento. During his senior year, he took his accordion and some recording equipment into the bathroom across the hall from the radio station—he really liked the acoustics in there—and recorded “My Bologna.” The Knack really dug it, finding it a suitable parody of “My Sharona,” and, more consequently, the song earned Al his first recording contract. After that, he hooked up with his manager, Jay Levey, who’s with him still, and—with the exception of John “Bermuda” Schwartz, whom he’d already been working with—all but one member of the band he’s with today.

The only formal training Al’s had in music—in anything except architecture, really—are three years of accordion lessons his parents encouraged him to undergo as a kid. All of the aptitude he exhibits now—not just for writing, but for vocals, for musical composition, for video direction, even for dancing and physical comedy—has pretty much been acquired on the job. “I do things I’m not qualified to do,” he said, “and I keep doing them until I get good at it.”

He still plays the accordion, of course, in a fresh polka medley of popular songs to appear on each new album. Many consider these polka medleys the black jelly beans in Weird Al’s bag, and even though I agree with them, I’m still happy they’re there. They’re part of what gives him his identity and authenticity—his indefinable integrity. They’re part of what makes him iconic and unique.

Al in 2013. Photo: Kyle Cassidy, via Wikimedia Commons

Just because he makes it look easy doesn’t mean it is. You listen to a song like his Beach Boys pastiche, “My Pancreas,” and just know Al isn’t bringing all that biological/anatomical expertise straight to the writing desk. “I knew a little bit about how the pancreas worked,” he said, “but not enough that I could write an entire song about it. So I went online and I did a lot of research about the pancreas. Back in the eighties, in pre-Internet days, I would go to the local public library and I’d check out books and I’d look at reference material and I would xerox things off the library photocopier. I would learn as much as I could, like I was doing a senior project on something, before I even started writing the lyrics, because I wanted to present the best possible version of my subject matter.

“All of my songs are carefully written,” he said. “They’re crafted. It’s not like I freestyle with lyrics that I spit off the top off my head. Everything is done with a lot of care and precision. If they need to be outlined, if the lyrics need a lot of research, or analytical observation, I put in the time.” He elaborated further:

Usually when I write a song, and I’ve come up with a concept for it, I’ll generate pages and pages and pages of ideas, jokes, and gags based on the song, just random words and phrases that have anything to do with the concept … as much material as I possibly can. And then later I’ll go through that and I’ll pick out what I think the best ideas are. And if there’s a joke I really want to make, I’ll go, Okay, if I want to use this line, then what can I rhyme that with? … It’s a very long and drawn-out analytical process. But that’s why I’m able to craft something that I think takes advantage of all the options that I have.

A lot of time is freed up in the efficiency of his methodology, no wasted motion in his machinery. Much of his editing happens “in the conceptual stage,” he said. “I generate a million ideas, and then I boil them down to my twelve favorite ideas for songs, and then will pour all my energy into those ideas and write those twelve songs as best as I can. And all twelve make the album. There are no B cuts, there’s nothing in the vault; it’s all exactly what I set out to do.”

One of the more wonderful things about observing Weird Al’s career is that there’s no typical Weird Al song. He seems intent on working in every musical mode and style, indulging every comedic and linguistic impulse. He might do a pastiche of Bob Dylan, comprised entirely of anagrammatic nonsense, calling it “Bob”—which is, expert linguists will notice, itself an anagram. Or he might tell hyperbolically grandiose tales about Charles Nelson Reilly in the style of the Truth About Chuck Norris book (although Al made sure to inform me that the Chuck Norris jokes weren’t his only inspiration for “CNR”: “It’s a comic trope that’s been around a long time, and that’s just something I thought would be fun”). Or he might, as he does on Mandatory Fun in what’s become the album’s most popular video, “Word Crimes,” completely repurpose a popular, controversial song (“Blurred Lines”) as a grammar tutorial. (It should be mentioned that, although I don’t have the heart to mention it myself, in every interview Weird Al has given, including this one, he’s consistently committed a rather egregious and aggravating word crime of his own, using the pronoun that instead of who even when the object is another human being—as in, “I enjoy sometimes being around people that are high, because it’s easy to make them laugh.”) Or he might even pop up performing on somebody else’s signature franchise—The Simpsons, say, or, as he did most recently, Epic Rap Battles of History. (When I express genuine surprise that he let the show’s creators write his lyrics for that one—he played Isaac Newton battling Bill Nye the Science Guy and Neil deGrasse Tyson—he says, “If it sucked, I would have rewritten it. But it was great.”)

The first time he ever did a cameo was The Naked Gun (1988). Al was single then, and he took a series of first dates to the movie, not telling any of them he was in the film. When he’d show up on screen emerging from that airplane, “they just flipped out,” he told me, especially when they realized he was wearing that exact same Hawaiian shirt, in two totally different realms yet at exactly the same time.

Lary Wallace is an eccentric at large and the features editor of Bangkok Post: The Magazine.

The Perils of Value Judgment, and Other News

Preference: it’s a good thing.

RIP, Lauren Bacall. “Her simplest remark sounded like a jungle mating call, one critic said.” (He meant it as a compliment—I think … )

Michel Gondry’s new film, Mood Indigo, is based on L’Écume des Jours, a 1946 novel by Boris Vian whose title “literally means either ‘The Foam of the Days’ or ‘The Scum of the Days’ but has been translated as ‘Froth on the Daydream,’ ‘Foam of the Daze,’ and—after the Duke Ellington song—‘Mood Indigo.’ The problem of translating Vian doesn’t end with titles. His books are crawling with wordplay: puns, mixed metaphors, neologisms, you name it.”

Speaking of translational difficulties, here’s how to give yourself an anxiety dream: just before bed, imagine being the first translator to attempt War and Peace or Anna Karenina. “Not only was the sheer prolixity of Tolstoy’s great novels a deterrent to all but the most determined of translators, but after the urbane Turgenev, whose measured prose slipped so easily into English, Tolstoy was also far more unpolished, more uncompromising and, well, altogether more Russian.”

How to give yourself an anxiety dream, part two: like everything on Facebook and watch as your hyper-personalized world crumbles around you. “Literally everything Facebook sent my way, I liked—even if I hated it. I decided to embark on a campaign of conscious liking, to see how it would affect what Facebook showed me … I began dreading going to Facebook. It had become a temple of provocation … By liking everything, I turned Facebook into a place where there was nothing I liked.”

Is the science-fiction writer R. A. Lafferty due for a comeback? “Lafferty’s most accessible and widely read novel, Space Chantey, is a psychedelic, Homeric odyssey in which space captain Roadstrum leads an expedition to the pleasure planet Lotophage, where the immortal houri Margaret tells him, very wisely, that ‘there are worse places to live than in tall stories.’ ”

August 12, 2014

Sartre and Borges on Welles

Theatrical release poster, 1941

In a sense, that poster doesn’t lie: everyone was talking about Citizen Kane. In another, more accurate sense, that poster does lie: not everyone was joining in that “It’s terrific!” chorus.

I hadn’t known, until Open Culture told me earlier today, that Sartre and Borges numbered among Kane’s more outspoken critics. Sartre reviewed the film in 1945, meaning he took four years even to bother seeing it. His is a damning appraisal not just of the movie but—kind of toothlessly—the whole United States cinema culture:

Kane might have been interesting for the Americans, [but] it is completely passé for us, because the whole film is based on a misconception of what cinema is all about. The film is in the past tense, whereas we all know that cinema has got to be in the present tense. ‘I am the man who is kissing, I am the girl who is being kissed, I am the Indian who is being pursued, I am the man pursuing the Indian.’ And film in the past tense is the antithesis of cinema. Therefore Citizen Kane is not cinema.

Not exactly an open-and-shut syllogism, but that’s in keeping with the Continental tradition, I guess.

Borges reviewed Citizen Kane in 1941—in fact, he reviewed many a film in his day, among them King Kong, The Petrified Forest, and Sabotage (the 1936 classic, not the 2014 Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle). Many of these can be found in his Collected Nonfictions. As the translation below attests, his review of Kane is typically well observed, though he’s kind of hard on Rosebud, and we can now say, from the vantage of more than fifty years, that he was dead wrong about the whole endurance thing:

AN OVERWHELMING FILM

Citizen Kane (called The Citizen in Argentina) has at least two plots. The first, pointlessly banal, attempts to milk applause from dimwits: a vain millionaire collects statues, gardens, palaces, swimming pools, diamonds, cars, libraries, man and women. Like an earlier collector (whose observations are usually ascribed to the Holy Ghost), he discovers that this cornucopia of miscellany is a vanity of vanities: all is vanity. At the point of death, he yearns for one single thing in the universe, the humble sled he played with as a child!

The second plot is far superior. It links the Koheleth to the memory of another nihilist, Franz Kafka. A kind of metaphysical detective story, its subject (both psychological and allegorical) is the investigation of a man’s inner self, through the works he has wrought, the words he has spoken, the many lives he has ruined. The same technique was used by Joseph Conrad in Chance (1914) and in that beautiful film The Power and the Glory: a rhapsody of miscellaneous scenes without chronological order. Overwhelmingly, endlessly, Orson Welles shows fragments of the life of the man, Charles Foster Kane, and invites us to combine them and to reconstruct him.

Form of multiplicity and incongruity abound in the film: the first scenes record the treasures amassed by Kane; in one of the last, a poor woman, luxuriant and suffering, plays with an enormous jigsaw puzzle on the floor of a palace that is also a museum. At the end we realize that the fragments are not governed by any secret unity: the detested Charles Foster Kane is a simulacrum, a chaos of appearances. (A possible corollary, foreseen by David Hume, Ernst Mach, and our own Macedonio Fernandez: no man knows who he is, no man is anyone.) In a story by Chesterton—“The Head of Caesar,” I think—the hero observes that nothing is so frightening as a labyrinth with no center. This film is precisely that labyrinth.

We all know that a party, a palace, a great undertaking, a lunch for writers and journalists, an atmosphere of cordial and spontaneous camaraderie, are essentially horrendous. Citizen Kane is the first film to show such things with an awareness of this truth.

The production is, in general, worthy of its vast subject. The cinematography has a striking depth, and there are shots whose farthest planes (like Pre-Raphaelite paintings) are as precise and detailed as the close-ups. I venture to guess, nonetheless, that Citizen Kane will endure as a certain Griffith or Pudovkin films have “endured”—films whose historical value is undeniable but which no one cares to see again. It is too gigantic, pedantic, tedious. It is not intelligent, though it is the work of genius—in the most nocturnal and Germanic sense of that bad word.

“This is a labyrinth of a movie with no way out,” Welles later said in response. “Borges is half-blind. Never forget that. But you know, I could take it that he and Sartre simply hated Kane. In their minds, they were seeing—and attacking—something else. It’s them, not my work.”

Whatever gets you through the night, Orson.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers