The Paris Review's Blog, page 669

August 27, 2014

The Ultimate Example of Everything, and Other News

John Ashbery at the Brooklyn Book Festival in 2010. Photo: David Shankbone

Our poetry editor, Robyn Creswell, on the New Museum’s current show, “Here and Elsewhere”: “So many of today’s iconic images are made in the Middle East … For visual artists working from the region, this surfeit of spectacles poses a challenge. When everyday life—at least as it is experienced via a computer screen—regularly throws up these images of terror and drama and the technological sublime, how can a photographer compete?”

Ben Lerner at the Met: “What interests me about fiction … is in part, its flickering edge between realism and where a tear in the fabric of a story lets in some other sort of light.”

Things that—according to the students and faculty of the first Ashbery Home School, a new writing conference in Hudson, New York—John Ashbery is “the ultimate example of”: “surrealism, realism, hyperrealism, distance, proximity, translation, tradition, the grotesque, the beautiful, the blind, the all-seeing, the old, the young, the queer, the hetero, the hedgehog, the fox, the human, the alien, the bric-a-brac in the cupboard, the masterpiece on the wall, painting, cinema, architecture, life.” (NB the author of this list describes it as “incomplete and incompetent.”)

A brief history of the problem of sorting, classifying, and otherwise categorizing things: “It is tempting to think making categories is a straightforward scientific enterprise, and that debates will be clearly settled once we’ve amassed enough data. But the history of science shows this not to be the case … The nature of scientific categories is not merely an empirical issue; it’s also a philosophical one, and one affected by self-interest and social forces.”

Today, in posthumous gifts: more than three thousand of Doris Lessing’s books are to be donated to a public library in Zimbabwe, where she lived for twenty-five years.

August 26, 2014

Freak City

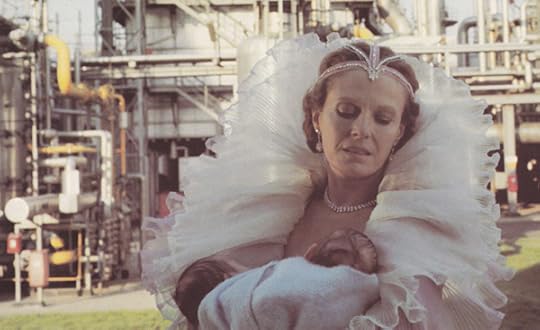

Film still from Ulrike Ottinger’s Freak Orlando.

Would it be frivolous to bring a class-action lawsuit against the Emmys? I can’t be the only one who slept poorly and, when she did drop off, slid into nightmare. One assumes productivity suffered. Wages and jobs may even have been lost.

It’s not just the contrast to the state of the world and the country that rankles. This is the nature of the beast. Opening monologues based on racial tensions and international crises have never been calculated to keep network viewers glued to the screen. It's not merely the crumminess of the writing, which was stale and dull, full of hoary, tone-deaf jokes and bits that would have felt démodé on The Benny Hill Show. Or even the monotony of the awards themselves, which overwhelmingly favored a couple of programs; a rout is never very entertaining.

People looked creepy. I know we all realize this, but it bears repeating. We are as physically grotesque right now as at any time and place in human history. The face-lifts, the fillers, the wasted, sinewy limbs are now the rule, not the exception. We all know why; the fetishization of youth—and its spiritual implications—are recognized by everyone. And yet, our cultural tolerance for true unnaturalness is unbelievably high. This is horrifying, but it is also fascinating. And this has got to be a unique moment: within five years, plastic surgery techniques will have evolved. Makeup artists and chemists will have better adapted to the harshness of HD. In a decade, we’ll look back with shock at what we accepted as normal and desirable. Never before, and never again, will things be as bad. Relish it.

Over the weekend, I went to see a little-screened West German comedy from 1981, by the avant-garde filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger. It was part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Strange Lands: International Sci-Fi series, although—as the curator pointed out when introducing the movie—Freak Orlando is not, strictly speaking, science fiction. It is, rather, a chaotic, low-budget, campy spectacle that feels like a particularly interminable performance by the Bread and Puppet Theater, if that venerable guerrilla-art troupe decided to cross Virginia Woolf’s Orlando with Tod Browning’s Freaks. Perhaps predictably, it drew a (sparse) crowd of hard-core cineastes, genre enthusiasts, and cranks.

Like the Woolf novel, the film ranges across the centuries and follows a gender-bending protagonist, although in this case all the action takes place in a garish universe known as Freak City, populated by the sorts of characters who inhabit Browning’s famous sideshow: two-headed women, hermaphrodites, conjoined twins, midgets. By the time we have gotten through the Spanish Inquisition and Holocaust references and reach the film’s denouement—a pageant to crown “the World’s Ugliest Person,” which is won by the normal-looking salesman who wanders in by mistake—we get the idea: Capitalist society is shallow, sexist, myopic, and cruel. Gender is a construct. Religion is arbitrary. Lunatics run the asylum. Beauty is subjective.

At the time, I found it heavy-handed. But then, last night, I watched the Emmys. And it was so much more grotesque than anything Ottinger could have imagined. From the polished fingers creeping across the mani-cam like an army of James Joyces, to those orange, emaciated—yet muscular!—arms, it was, as my mother would say, beyond parody. We are living in a world between genres, and it’s awful. For a while I thought, Where is our Grosz, our Otto Dix? Who will show us for what we are when life becomes so obvious and heavy-handed? And then, of course, I glanced up, and saw someone’s under-eye concealer exposed by the unforgiving glare of the HD, and realized I was looking at it.

The Shape of a Life

Notes for Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life.

Congratulations to Hermione Lee, who has won the 2014 James Tait Black Prize for her biography of the Booker Prize–winning novelist Penelope Fitzgerald. One judge described Lee’s biography as “a masterclass in writing of this type … the perfect marriage of an excellent subject and a biographer working at the very top of her game.”

Lee was at work on the book during her Art of Biography interview last year: in the course of their conversation, Louisa Thomas discovers a blanket-covered box that contains the Fitzgerald family archive. Though Lee denies having set out to be a “woman writer writing about women writers,” she has almost exclusively chosen women authors as her subjects. Still, for a biographer of Woolf, Cather, Wharton, and Bowen, Lee found Fitzgerald to be a special case:

I don’t have a theory about Penelope Fitzgerald. I’m deeply interested in the shape of her life, and I’m fascinated by lateness, late starts. She didn’t start publishing novels until she was sixty, for a variety of reasons. I feel there was a powerful underground river running through her life. She was a brilliant young woman, and everybody thought she was going to be a writer and she was writing away like mad in her teens and early twenties, and she was the editor of a magazine. And then it all went underground. Meanwhile, she’s writing notes in her teaching books, which are a form of apprenticeship, and she’s bringing up her family, and she’s coping with her husband. And then he dies. And then up it comes, this underground river, at the age of sixty, and she writes thirteen books in twenty years. I don’t have a theory about that. Nor do I want to blame anyone. But I want to understand it and show it happening as best as I can.

The complexity of women’s lives is, naturally, at the center of Lee’s interview, and it’s a thread that connects Lee to her subjects intimately. The first woman to hold the Goldsmiths’ Chair and the first woman president of Wolfson College, Oxford, she recalls walking across the grass of New College and thinking of Virginia Woolf, who, in trespassing momentarily on the lawn, was chased off by a beadle. As Woolf writes in A Room of One’s Own, “Instinct rather than reason came to my help, he was a Beadle; I was a woman. This was the turf; there was the path. Only the Fellows and Scholars are allowed here; the gravel is the place for me.”

Lee, however, feeling the benefit of the “strenuous labors of my female predecessors,” can stray from the path; she makes a point of walking across the grassy quad, because “I had the right to be there.”

The Great Unread

Why do some classics continue to fascinate while others gather dust?

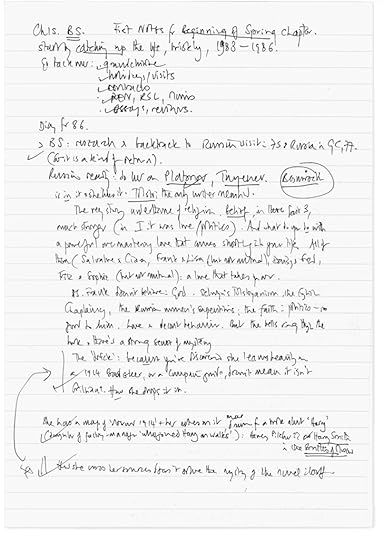

An illustration by Attilio Mussino from a 1911 edition of The Adventures of Pinocchio.

Even in our era of blurb inflation, it’s hard to top Giuseppe Verdi’s claim that Alessandro Manzoni’s novel The Betrothed (1827) was “a gift to humanity.” Verdi was hardly alone in praising the author, who ranks second only to Dante in Italian literary history. Manzoni’s contemporaries Goethe and Stendhal celebrated his genius, while the critic Georg Lukács said that The Betrothed was a universal portrait of Italy so complete that it exhausted the genre of the historical novel. In Italy, such is the ubiquity of Manzoni’s novel that Umberto Eco claimed “almost all Italians hate it because they were forced to read it in school.” Manzoni was named senator in 1860 by the Italian government; in his greatest honor, Verdi dedicated his Requiem to him on the one-year anniversary of his death.

So why do few outside of Italy care about Manzoni—or, even more tellingly, why do they care much more about other books, written around the same time as The Betrothed and devoted to themes similar to its own? By comparison, one of the best-selling Italian books of all time is Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (1881), the story of a mischievous puppet who dreams of becoming a boy. The scholar Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg has shown that Pinocchio, in his struggle to assert his individuality against the controlling wishes of the outside world, represented the archetypal Italian child in the newly formed nation: the book first appeared twenty years after unification. Similarly, Manzoni’s Betrothed gives us two typical Italian peasants, Renzo and Lucia, who struggle to marry and build a life together amid class inequality, foreign occupation, and church domination.

But here the similarities end: Manzoni’s novel promotes a Christian faith whose adherents are rewarded for submitting to God’s providential wisdom. Collodi’s story, beyond exploring the plight of Italians in their newborn nation, describes how children learn to make their way in an adult society, with all its strictures and codes of behavior. Manzoni’s legacy in Italy is so strong that his book will always be read there. But outside of Italy, those same readers curious about Collodi’s star-crossed puppet are likely never to give Manzoni’s thoroughly Christian universe a second thought.

This contrast, between a celebrated and largely unread classic and an enduringly popular classic, shows that a key to a work’s ongoing celebrity is that dangerous term: universality. We hold the word with suspicion because it tends to elevate one group at the expense of another; what’s supposedly applicable to all is often only applicable to a certain group that presumes to speak for everybody else. And yet certain elements and experiences do play a major role in most of our lives: falling in love, chasing a dream, and, yes, transitioning as Pinocchio does from childhood to adolescence. The classic that keeps on being read is the book whose situations and themes remain relevant over time—that miracle of interpretive openness that makes us feel as though certain stories, poems, and plays are written with us in mind.

In his Defence of Poetry, Percy Bysshe Shelley writes that great literature is “a fountain forever overflowing with the waters of wisdom and delight; and after one person and one age has exhausted all its divine effluence … another and yet another succeeds, and new relations are ever developed.” Shelley understood that some works have the magical capacity to resist closure—they read us as much as we read them, by revealing what is most important to our lives individually and our age collectively. Each great book, Shelley writes, is “the first acorn, which contained all oaks potentially”: the meaning we derive from literature changes over time, though the words on the page remain the same.

Sometimes we even look for meaning that isn’t really there—at least not in the way that the author intended it. In 1756, Voltaire proclaimed “nobody reads Dante anymore,” and indeed the Enlightenment had little time for Dante’s religious allegories and Christian doctrine. He was about to go the way of Manzoni’s Betrothed: a classic that was once much admired but now rarely read. Then the Romantics came along and rediscovered Dante, celebrating his individuality and heroism—those same qualities from Inferno that Dante would reject in Paradiso. But that didn’t matter to the Romantics. They creatively misread Dante, and in so doing made him the literary touchstone he is today. Our interest in Dante’s hell, the universality of its concern with questions of justice and crime and punishment, overrides our indifference to his medieval vision of Christianity.

Manzoni famously announced that The Betrothed would reach only “twenty-five readers,” yet his book became a national treasure. Its inability to attract a non-Italian audience isn’t the result of its artistic shortcomings, but of the nature of its questions and themes, which simply don’t appeal to a contemporary audience. No literary work can predict the future, but some do a better job than others in carving out a space for readers of all types and from all epochs. Where Manzoni failed, others, like Collodi, succeed. Manzoni’s novel exudes a Christian faith at odds with an increasingly secularized world; Collodi’s focuses on the eternal plight of children in the land of grown-ups.

W. E. B. Du Bois defended the necessity of a liberal arts education for recently emancipated African Americans by saying, “I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not.” Separated from Shakespeare’s Elizabethan England by centuries, he still found in the plays a universal space where he could explore his common humanity with Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello. The greatest defense of the classics, he understood, was to keep reading them—and to let them keep reading us.

Joseph Luzzi teaches at Bard and is the author of the new memoir My Two Italies .

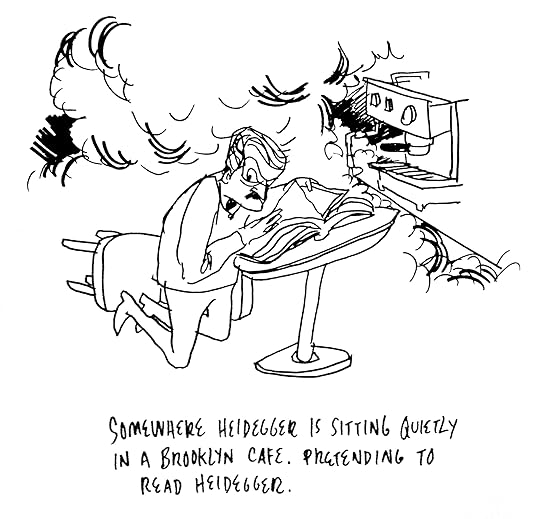

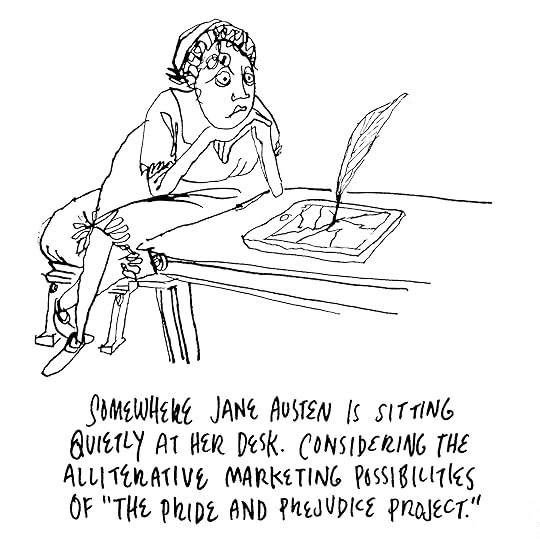

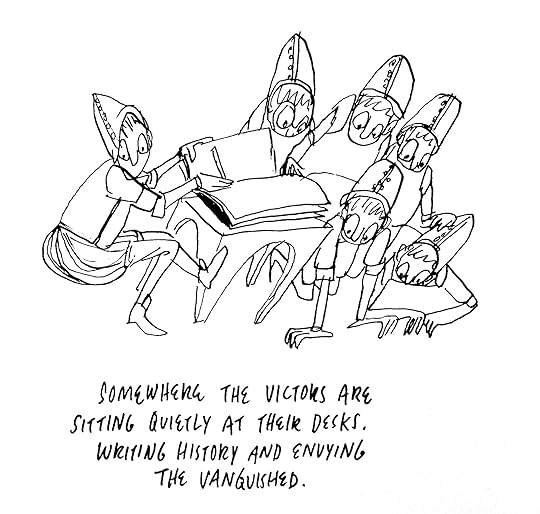

Where Are They Now? Part Two

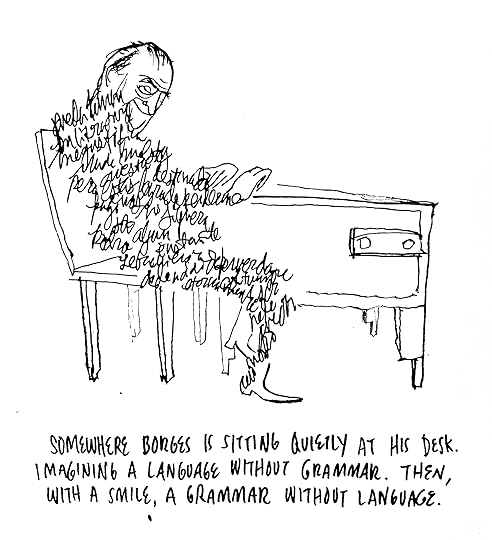

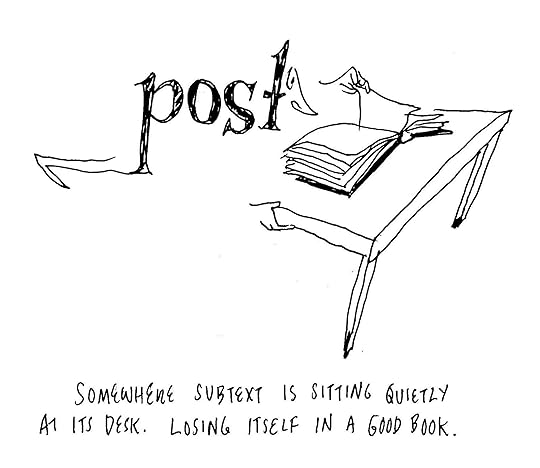

The second in a week-long series of illustrations by Jason Novak, captioned by Eric Jarosinski.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist in Oakland, California.

Horseback Balloonist, and Other News

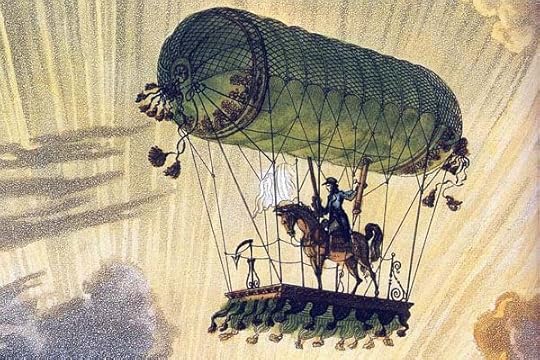

What one did for fun in the eighteenth century. Image via Retronaut

Blootered, plonked, fuddled, muckibus: what we talk about when we talk about getting wasted.

An interview with Rachel Cusk, whose new novel, Outline, is serialized in The Paris Review: “I’m certain autobiography is increasingly the only form in all the arts. Description, character—these are dead or dying in reality as well as in art.”

James Wood on James Kelman: “Kelman’s language is immediately exciting; like a musician, he uses repetition and rhythm to build structures out of short flights and circular meanderings. The working-class Glaswegian author knows exactly how his words will scathe delicate skins; he has a fine sense of attack.”

In the UK, literature in translation is enjoying a surge in popularity. “There used to be a feeling translations were ‘good for you’ and not enjoyable … like vegetables … But actually they’re wonderful books.”

“Pierre Testu-Brissy was a pioneering French balloonist who achieved fame for making many flights astride animals, particularly horses.”

August 25, 2014

Charmed Objects

An example of a Phantom Shelf. Credit: EM Photography

People talk about a “Keeper Shelf” for those books they love more than any others. Those which, I suppose, are worth owning in this time when owning a physical book means something more than it once did. (Or, as much as it once did.) For my money, though, there is no better proof of love for a title than not owning it—that is to say, having given it away. Call it the Phantom Shelf.

When my coffers are in a particularly robust state, I will sometimes indulge in the extravagance of replenishing those favorite books I am most inclined to give away. It is always the same few—titles that I need to share with someone like-minded, right now!—and by the same token, those which I always miss when they are gone. They are, in alphabetical order:

Pitch Dark, by Renata Adler

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, by Barbara Comyns

Don’t Look Now, by Daphne du Maurier (specifically for the novella “Monte Verità”)

In Love, by Alfred Hayes

A Girl in Winter, by Philip Larkin

Climates, by André Maurois

After Claude, by Iris Owens

Excellent Women, by Barbara Pym

Loitering with Intent, by Muriel Spark

In the nonfiction category, I can’t seem to hold onto Stevie Smith’s Cats in Colour, Among the Bohemians by Virginia Nicholson, E. B. White’s collected essays, and The Secret Life of the Lonely Doll by Jean Nathan.

I don’t know why this should be so: There are plenty of titles I would recommend—Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea; Elena Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment; Laurie Colwin’s Home Cooking, Shirley Jackson. Yet in each case, I still retain my original copy; I have had to replace each of the others at least twice.

It is always nice to give someone the treat of a great read; there is no storyteller like du Maurier, and so many people stop at Rebecca! It was pure chance that I didn’t myself! Sometimes you are trying to give not just the book but the author—when you recommend Excellent Women or Who Was Changed or the Spark, you are really recommending every book that each of them has ever written. It could as well be A Few Green Leaves or The Ballad of Peckham Rye. Sometimes it is needing desperately to share the vocabulary of a book, or even the book’s flaws—to burst with the desire to analyze the characters of Climates, or to know without having to talk about it just how messed up the whole Lonely Doll story really is. (In fairness, I also feel this way about Scotty Bowers’s Full Service, but I understand this to be a more rarified taste.)

I love to give things away, to a degree I am not sure is healthy. Not just books—music, food, clothes. Few leave my home empty-handed, whether or not they want to. I like to share my enthusiasms. Now that I think about it, it is possibly pathological, maybe malevolent. Maybe I want to magically sneak into their homes, charming my books like genii. Maybe a part of me is just a megalomaniacal dictator who wants to impose a twee, mandated groupthink on everyone I encounter. (Although I must say, a world of people shouting—or blogging—about dollhouses and food all the time sounds nightmarish.)

But don’t people like getting recommendations? I don’t mean those things others think one ought to love (See: Dud Avocado, The), but those things about which they are genuinely passionate? It is a window into who another person is. And how else, after all, does anyone learn about anything? I’m eager to hear about others’ favorites, in any case, and hope you don’t mind. I’ll exert benevolent control, I promise. I won’t even make you read Full Service.

Last Chance

The manager of the LRB Cake Shop wandering the world for inspiration in Tokyo’s Narita Airport.

This is the final week to enter our #ReadEverywhere contest, celebrating our joint subscription deal with the London Review of Books, which ends on August 31.

To enter, just post a photo of yourself reading The Paris Review or the London Review of Books on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook—use the #ReadEverywhere hashtag and one of our magazines’ handles. (Those of you who have already posted photos, fear not—your work is in the running.)

Our three favorite contestants will receive these plush, severely enviable prize packages:

FIRST PRIZE ($500 value)

From The Paris Review: One vintage issue from every decade we’ve been around—that’s seven issues, total—curated by Lorin Stein.

And from the London Review of Books: A copy of Peter Campbell’s Artwork and an LRB cover print.

SECOND PRIZE ($100 value)

From TPR: A full-color, 47" x 35 1/2" poster of Helen Frankenthaler’s West Wind, part of our print series.

And from the LRB: Two books of entries from the LRB’s famed personals section, They Call Me Naughty Lola and Sexually, I’m More of a Switzerland.

THIRD PRIZE ($25 value)

From TPR: A copy of one of our Writers at Work anthologies.

And from the LRB: An LRB mug. (Never one to be outdone, the LRB is actually including a tote bag, some postcards, a pencil, and an issue with all of the prizes above. Retail value: inestimable.)

Hurry! August 31 is less than a week away.

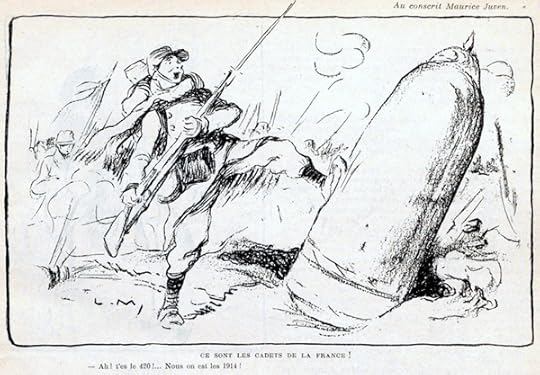

Les Combats Modernes

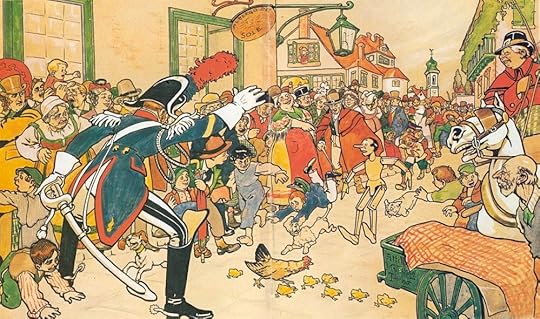

“Ce sont les cadets de la France!” (“These are the cadets of France!”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, No. 1, Nov. 21, 1914.

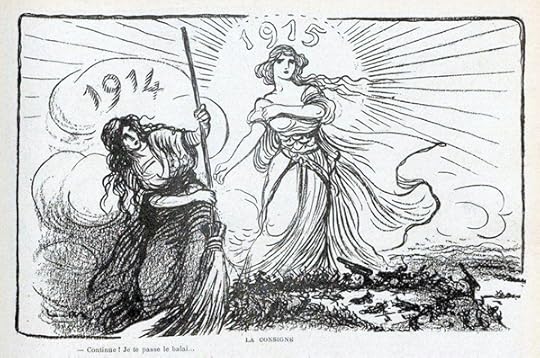

“La consigne” (“The Order”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, January 2, 1915.

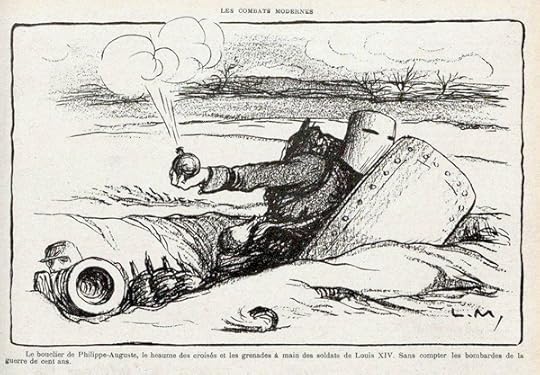

“Les combats modernes” (“Modern Combat”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, January 30, 1915.

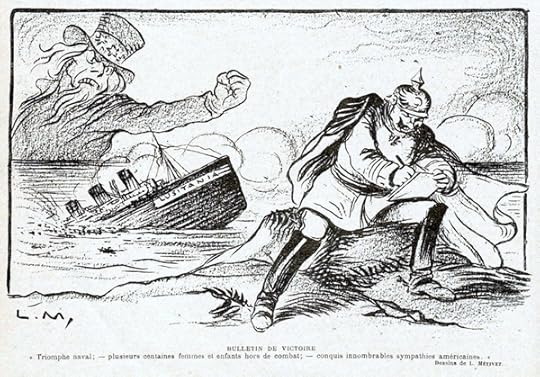

“Bulletin de victoire” (“Forecast of Victory”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, May 22, 1915.

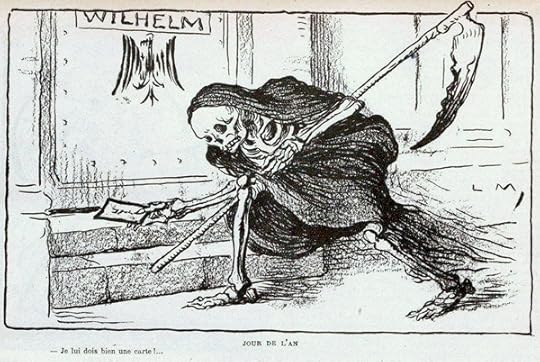

“Jour de l’an” (“New Year’s Day”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, January 1, 1916.

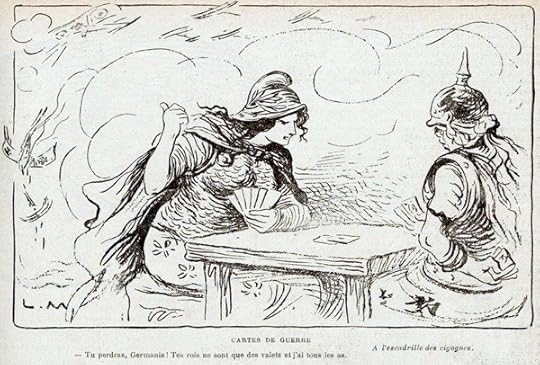

“Cartes de guerre” (“War Maps/War Cards”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, February 10, 1917. The phrase “cartes de guerre” means “war maps” but here it has a double meaning because “carte” is also the word for “card” (including the kind used in card games).

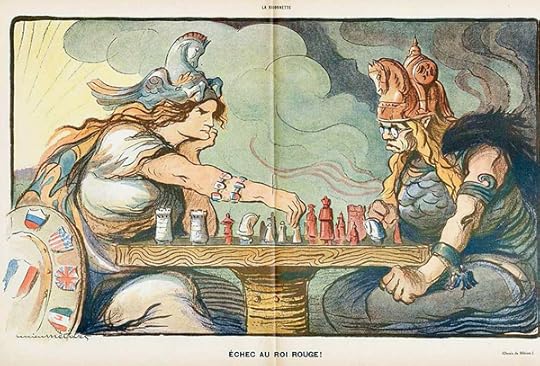

“Échec au roi rouge!” (“Check to the Red King!”), Lucien Métivet, centerspread from La Baïonnette, August 16, 1917.

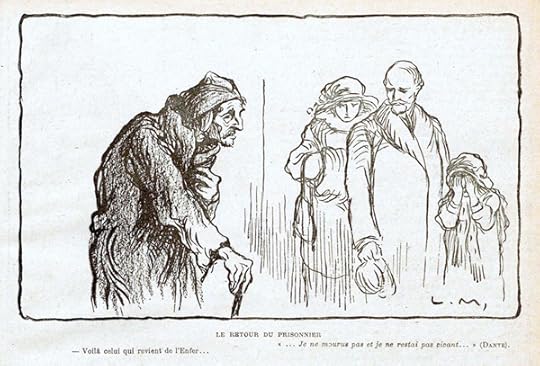

“Le retour du prisonnier” (“The Return of the Prisoner”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire Rouge, December 14, 1918.

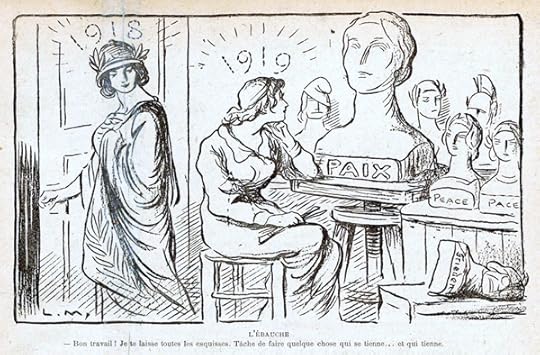

“L’ébauche” (“First Draft”), Lucien Métivet, from Le Rire, January 4, 1919.

Given the recent centennial of the beginning of the Great War (as it was then known), I’ve found myself thinking again of Lucien Métivet, the French artist I wrote about here last year, best known for his works from the 1890s. The advent of the war brought an abrupt halt to the publication of Le Rire (Laughter), the weekly journal of humor to which Métivet was a regular contributor, but its publisher, Félix Juven, soon relaunched it with a small but significant change of title: now it was Le Rire Rouge (The Red Laugh), presumably in recognition of the blood of France’s soldiers and the dark nature of the times.

It had become customary for Le Rire to start each issue with Métivet’s drawings up front, and in the journal’s first new issue, of November 21, 1914, his was the opening image: an energetic, optimistic young conscript. The picture’s cheerleading join-the-war-effort ambience is given a discreetly poignant touch by a telling detail just outside the frame: to the upper right we see the typeset words “Au conscrit Maurice Juven”—a dedication to a young conscript whose surname suggests a close relationship to the magazine’s publisher, a longtime friend of the artist. Clearly this dedicatee was, like all soldiers, carrying with him into danger the hearts of those who loved him. With this single, seemingly exuberant image, the very personal stakes for the creators of Le Rire Rouge, and indeed for all of France, were acknowledged.

That same opening page contained a note to readers, summed up in a quote from the dramatist Henri Lavedan: “Le soldat français rit, partout. C’est une de ses manières.” (“The French soldier laughs, everywhere. It’s part of his manner.”) True to its intentions as stated in that initial letter to readers, for the next four years Le Rire Rouge maintained, along with its new name, its new theme: the war in all its aspects, from the quotidian to the grim, served up in a range of styles but with loyalty to France never in doubt. The year 1915 began with a drawing depicting the passing of a giant broom from the previous year to the new, each of the “years” personified as a heroic woman (variations on Marianne, the Goddess of Liberty, a popular symbol of France), ready to sweep up the war. A few weeks later, a depiction of “modern combat” made reference to the shields, helmets, grenades, and cannons of wars past.

As Métivet continued to deliver his contributions, usually three images per week, and the months passed, perhaps these cartoons—which, like many editorial cartoons, were not always designed to provoke laughter but often rather a nod of recognition, and a sense of affirmation and solidarity—began to feel to readers like a chronicle of the era, albeit one entirely partisan to the French cause. In May, the United States’s outrage at the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine prompted Métivet’s “Bulletin de victoire” (“Forecast of Victory”), with its memorable depiction of a furious Uncle Sam; the forecast, however, was premature, as the U.S. was not in the least eager to enter the war. As the horrors continued, the darkness and bitterness of the times wove their way through the images of subsequent years, such as, for example, one for New Year’s Day 1916 in which the Grim Reaper pays a courtesy call on Kaiser Wilhelm II (“I owe him a card!”).

In February 1917, Métivet portrayed war as a game of cards between the valorous Marianne-as-warrior-woman and an ugly, brutish warrior hag—his standard depiction of Germany, often accompanied by vultures and skulls. France has “all the aces,” thanks to the cigognes (“storks”) air force squadron to which the drawing is dedicated. Six months later, Métivet recast this image for La Baïonnette, another war-themed publication, transforming the game of cards into one of chess. As a color center spread, more than four times the size of its black and white prototype, the reworked version provided a canvas well suited to Métivet the renowned poster artist, with his longstanding taste for the symbolic. We see in the lower left that the French shield is decorated with the emblems of its Allies (now including the United States), as the warrior-goddess, clearly out of patience, makes a critical move toward winning the game. Battlefield smoke forms a backdrop, but a glorious sunrise is breaking behind the winner-to-be. And in a detail characteristic of Métivet at his best, the helmets of each player form a parallel staging of the drama: each takes the shape of a horse in battle. France’s helmet is Pegasus, rearing up to fly to victory—a victory that in reality was still more than a year away.

Le Rire Rouge continued on through the Allied victory in November 1918 and for several subsequent weeks, ending with issue number 215, dated December 28, 1918. Two weeks prior, Métivet had included among his contributions a simple drawing titled “Le retour du prisonnier” (“The Return of the Prisoner”) that acknowledged the personal devastation apparent in those who had “returned from Hell” as broken men. Its pathos is too deliberate, too conventional, to impress one as art, but its worth is in its gesture of humanity. As I look at it I think back to the image with which Le Rire Rouge began—that eager young conscript—and I wonder what became of Maurice Juven.

I do know what Félix Juven did next. With his magazine’s first issue of the new year, dated January 4, 1919, he dropped the word “rouge,” reset the numbering to indicate a new series, and Le Rire returned. Issue No. 1 opened with a Métivet drawing that addressed the hope of a lasting peace, with the title “L’ébauche,” which can mean “first draft,” “first signs,” or “beginning.”

Robert Pranzatelli is the founding editor of the Folio Club , an independent publishing project. He is also a longtime staff member of Yale University Press.

Where Are They Now? Part One

The first in a week-long series of illustrations by Jason Novak, captioned by Eric Jarosinski.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist in Oakland, California.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers