The Paris Review's Blog, page 668

August 29, 2014

The Dreams in Which I’m Dying

The vanity of the zombie apocalypse.

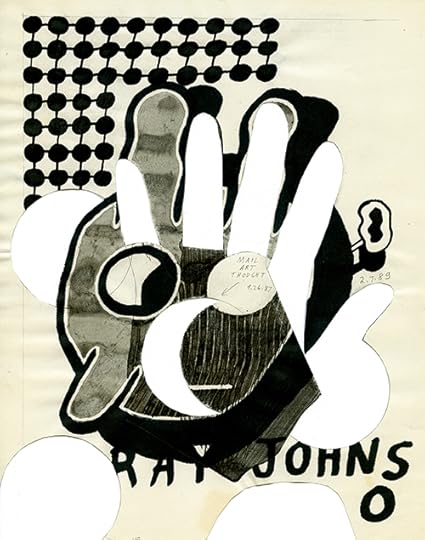

A publicity still from The Last of Us.

There are few things as narcissistic as an apocalypse fantasy. The apocalypse doesn’t mean the end of the world, just the end of humankind, and considering such a fate can lead us into a sentimental peace with the present day. Suddenly, in spite of all its flaws—flaws that might be harder to accept in less dire circumstances—the world seems worth keeping intact. In recent years, zombies have been a catalyst of fictional doom in every conceivable manner, from popular horror and comedy to moral parable and literary send-up. They offer us freedom from death in exchange for our subjective consciousness and social identity. But we’d sooner have death, if it means our egos can be spared for a bit.

The Last of Us, a PlayStation game whose latest version was released last month, is a story about a zombie apocalypse, but it wasn’t supposed to be. Its creative director, Neil Druckmann, said in a 2011 interview that he wanted the game to be more of a love story, one between a middle-aged man and a fourteen-year-old girl. So maybe it’s more accurate to describe The Last of Us as a story about a kind of taboo love that requires a zombie apocalypse to normalize—and, by extension, a story that, through love, gives the fungal zombification of humanity a silver lining. Our species may be on the verge of extinction, but if we’re able to fall in love and learn a little about ourselves along the way, it can’t be all bad. Love is where all educated people go to bury their narcissism.

The idea for the game dates back to a 2006 BBC documentary—part of the Planet Earth series—that showed the effects of the Cordyceps fungus on ants. The parasitic growth infests the ant host and begins to replace its tissue with fungal material until the entire body has been eaten away. The fungus can influence the ant’s movement, causing its jaws to open and close sporadically and driving it to cling to tree leaves in warm spaces ideal for continuing growth. Druckmann immediately recognized the ramifications that such a relationship might have in a story about human extinction. Soon the creative spores for the game were drifting through his brain.

In The Last of Us, this fungus afflicts people. The game’s protagonists, Joel and Ellie, bond with one another during the awkward limbo phase of the apocalypse, when most of the damage has been done but not quite everyone has been snuffed out. They fall in love between killing fungal zombies with crowbars and shooting scattered human outlaws. Joel is a single dad from a Texas suburb—a short prologue lets us play as his daughter, Sarah, home alone experiencing the first wave of police sirens, terrified news reports, and power outages as the zombies appear in town. A soldier shoots both Joel and Sarah, thinking they’re infected; as Sarah whimpers her last few breaths in Joel’s arms, he quietly begs her to stay alive. “Please don’t do this to me,” he says, as if being shot was a thing kids did to their parents.

Twenty years later—when most of America has been wiped out by the fungal scourge, with ivy eating away building walls and abandoned quarantine zones left to be picked over by armed looters—Joel has migrated to Boston, and we meet Ellie, a fourteen-year-old girl whom a militant group called the Fireflies believes can save the world. Ellie was bitten by a zombie, but she appears to be immune, and so they want to get her to a lab to try and engineer a vaccine from her magical body. Joel agrees to escort her to the other side of Boston, which, in the fashion of complication-driven road stories, ends up stringing them along to Pittsburgh, and then to Colorado, and finally to Utah.

Ellie’s not quite a replacement daughter for Joel, nor is she a friend, and the game seems oblivious to any sort of sexual tension between the two. And though the plot distinguishes her as a figure of mystic privilege, the lone immune human in a country of three hundred million plagued, she’s not given any messianic pomp. It makes more sense to think of Ellie and Joel not as characters but as symbiotic symbols that need each other to reach maximum cathartic signification. All videogame characters carry the weight of what players want to be true of the world, and so Joel and Ellie must serve the dual purpose of revealing how horrible the apocalypse is—forcing them to kill in increasingly gruesome ways—while making the case that humans deserve, if not a reprieve, then at least some sentimental gratitude for the warmth and intimacy they brought to the world.

The Last of Us depicts the zombie end-times in a way that endorses a basic fear of other people. Zombies have always functioned as emotional shorthand for a condition in which it’s morally allowable to attack everything, to see every encountered life as a possible threat, while resenting or mistrusting the last few survivors. The game’s humans are hostile to both the zombies and one another, fighting petty skirmishes over remnant sacks of sugar and rubbing alcohol while leaving mazes of armaments and munitions in their wake—cold, cubist structures that feel inhospitable and alienating as soon as they’re deprived of electricity. There’s little joy, cooperation, or generosity between anyone here. “You survived because of me,” Joel tells his brother, Tommy, when they’re finally reunited years after having parted ways. “It wasn’t worth it,” Tommy says. We have a habit of imagining others this way, romanticizing our own struggles while villainizing everyone else’s—seeing, in a documentary about ants, a way to make this intimate discomfort with other life seem justified.

The underlying expectation here—that without Western civilization humans would become monsters—is a psychic tic of game designers, who tend to be overeducated upper-middle-class men whose primary lens for understanding the world comes from commercial entertainment. If your worldview is built around a series of compromises you’ve made to secure a comfortable salary building eidolons of human narcissism into restricted-admission dream-states, paranoia and projected self-loathing are in order. And when these labors make you servant to an economy of Moore’s Law and inescapable obsolescence, the competition for scarce resources (conveniently abstracted in the game with overlaid icons, as if Google Glass were the only thing to survive the collapse of human civilization) must seem like an especially poetic prism.

The game’s greatest irony is its conclusion, which finally seems to admit that if narcissism must be the banner of our species, then it might be best to let us all die out. It turns out that to save humankind, Joel will have to watch as Ellie dies; for some reason the Fireflies need to kill her to research her brain and create their vaccine. And while Ellie appears ready to make that sacrifice, it sends Joel into a narcissistic tunnel: he ends up rescuing her unconscious body from the operating table at the last minute and then kills the woman who’d entrusted him with the mission at the beginning of the game. When Ellie regains consciousness, he tells her the Fireflies had been wrong about the immunity, and had studied several other immune cases from around the country before she arrived, concluding that there was nothing to be learned from them. The game ends with a mean-spirited close-up of her face as she questions Joel about the story, having a hard time accepting it could be true. We stare at her for a few seconds as she vacillates, and then she decides to accept the lie. “Okay,” she says.

It’s not by accident that the game immediately jumps forward twenty years after the death of Joel’s daughter in its first section, depriving players of the chance to experience Joel’s mourning, very probably because Joel didn’t mourn and because the people making the game probably could not have imagined a believable way to dramatize that mourning. It’s not by accident that industrial videogames—produced by hundreds of people for millions of dollars—cannot be about mourning, sorrow, or inaction. Shooters sell, and so the industry depends on its ability to produce fresh bodies to kill. It’s continually reinventing variations on the same basic moral context that makes it permissible to kill them. As a metaphor, The Last of Us is a suicide note for the human species, but as an object of paid-for culture, duplicated and distributed en masse, it’s a reminder of our sentimental preference for postmortem artifacts to living specimens. It’s easier to understand the idea of death than the reality of life, and so we make an industry of waiting, imagining our end lumbering toward our vain and cubicled bodies, inventing the selfish moral blank spots we suspect ourselves of being.

Michael Thomsen is a writer in New York and the author of Levitate the Primate: Handjobs, Internet Dating and Other Issues for Men. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Bookforum, The New Inquiry, and Guernica.

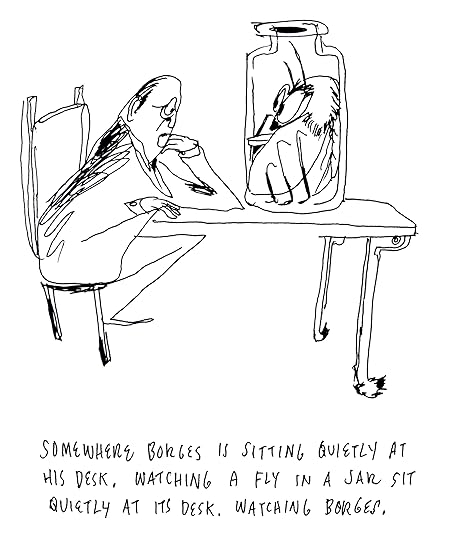

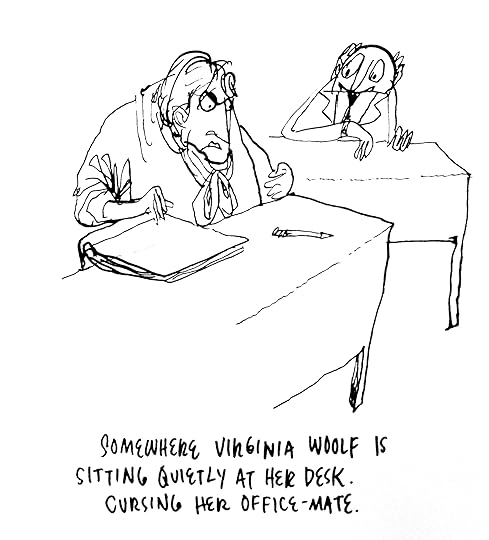

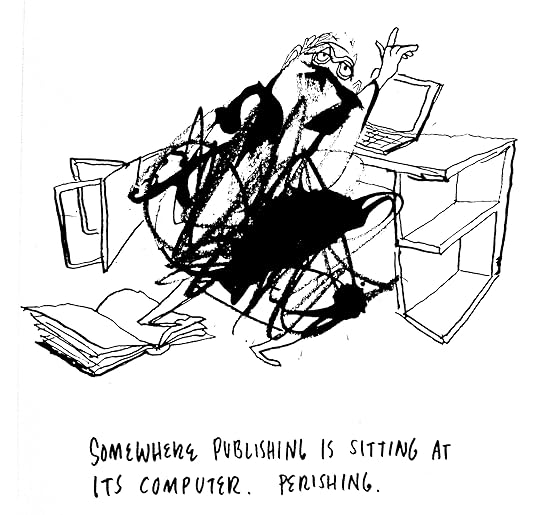

Where Are They Now? Part Five

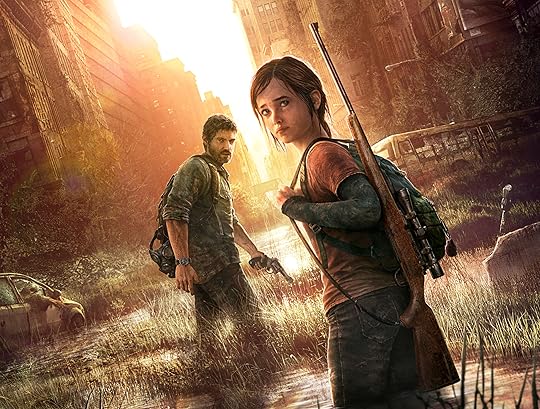

The last in a week-long series of illustrations by Jason Novak, captioned by Eric Jarosinski.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist in Oakland, California.

Telling It Like It Is in Times Square, and Other News

Alfredo Jaar, A Logo for America, 1987/2014. Photo: Ka-Man Tse for Times Square Arts

Coming this fall: a host of new books about football. But do they hold up against the venerable backlist of football literature?

Today in trepidatious grammatical hairsplitting: whoever versus whomever , and all the complications thereof.

On syllabus bloat: “Today’s college syllabus is longer than many of the assignments it allegedly lists … The syllabus now merely exists to ensure a ‘customer experience’ wherein if every box is adequately checked, the end result—a desired grade—is inevitable and demanded, learning be damned.”

Every night between 11:57 and midnight, the slogan “This Is Not America” has appeared on a high-definition LED in Times Square—a message from the Chilean conceptual artist Alfredo Jaar, who debuted the work in a decidedly more analog form back in 1987.

Science shows that listening to your favorite songs, regardless of their genre, will generate “strikingly similar brain activity patterns” of a sort that can encourage creativity.

August 28, 2014

For the 1 Train Dead

Robert Lowell at home.

New Yorkers like to affect jadedness in the face of celebrity; we yawn, we stare fixedly in the other direction, we scorn star-struck tourists And yet today, I had a celeb sighting so exciting I reacted like a middle-schooler at a taping of Total Request Live.

I had just entered a pleasantly empty subway car, only to discover the cause of its emptiness—a broken AC—too late. I was cursing my luck, and considering an illegal dash between cars, when I saw him. There, across the aisle, and under a “Poetry in Motion” poster, was Robert Lowell. To the life: the patrician features, the distinctive nose, eyes that had known suffering and pain, as well as realms of genius invisible to the normal run of mortals. He was not a man in the first blush of youth; this was “Day by Day”-era Lowell. He was wearing a rumpled linen jacket and tie. Of course he was.

All thoughts of changing cars having fled, I took a seat directly opposite and stared. There was no question about it: this was Robert Lowell. Maybe a ghost. At the very least a relative. He could certainly have made a good living as a Lowell impersonator, traveling the world and reciting confessional poetry with a Brahman inflection. Well, a living, anyway.

I waited for my chance. I didn’t want to strike too soon, but on the other hand I couldn’t live without knowing. Best-case scenario, he’d break into “Life Studies.”

I timed it carefully. When we were one stop away from my point of departure, I planted myself in front of him. “Excuse me, Sir?” I said, my voice quavering. He looked up. His eyes were very, very sad. “Has anyone ever told you how much you look like Robert Lowell?”

For a horrible moment, the lack of comprehension on his face was such that I thought he might not speak English. But then he said, “Robert who?”

There were two French tourists watching the proceedings with interest. Maybe they didn’t realize that other cars were air-conditioned.

“Robert Lowell, the poet,” I said. “It’s a compliment. He was an excellent poet! And handsome! I mean, he had his problems”—I said this in case he should look up his biography and think I had been less than forthcoming—“but who doesn’t?”

“Oh,” he said. “Thanks, I guess.”

I turned my back and stared at the doors for what felt like an eternity. It must have been a hundred degrees in there. Frankly, I thought, if that guy wasn’t Robert Lowell, and either mentally ill or supernatural, it was really weird that he was sitting in this sweltering car. Frankly, it was irrational.

Olympia by the Sea

The dashed ambitions of Brooklyn’s Marine Park.

The salt marshes of Marine Park. Photo via Baldpunk.com

There is a proud park on the watery edge of Brooklyn. It contains a pool, a little sandy beach, canoes and kayaks, new sporting fields of all kinds, gardens, an open-air theater, and a playground; nearby subway stops draw people from the extremes of the five boroughs. Today, this sounds more or less like Brooklyn Bridge Park, the enchanting construction facing downtown Manhattan and built through public-private partnership, as is the way of city planning these days. But almost ninety years ago, these were just the lesser diversions in the grand plans for Brooklyn’s Marine Park.

Take the B or Q train down, down, down to Kings Highway—bring a book or music, because it’s a ride. Get off there, find the B2 or B100 bus on Quentin Avenue, and ride that another fifteen minutes east, and you’ll find the modern Marine Park. (You can also ride the 2 or 5 to the end of the line, which requires two bus transfers, but you’ll get there.) Almost ten miles from City Hall, you’ll have reached the greatest graveyard of a mighty park that New York City has ever seen.

It started in 1911, when the famed designer of the Chicago Columbian Exposition, Daniel Burnham, was invited to Brooklyn with his partner Edward Bennett to design a blueprint for the borough’s expansion. They set aside a large area far and away to the southeast by Jamaica Bay, as “a littoral counterpoint to Prospect Park,” as Thomas Campanella, Marine Park’s assiduous (and perhaps only) historian writes. As Campanella has documented, this suggestion became a reality through the philanthropy of two prominent Brooklynites, Frederic B. Pratt and Alfred T. White. They bought up and gave to the city about a hundred acres of land for the park’s creation. The city was leery even then—there were murmurs that a park would do little more than increase real-estate value for homeowners in the region. The philanthropists sweetened the deal to include $72,000 dollars to pay for costs. “The donors owned no other land in the vicinity and did not expect to profit in any way from the gift,” promised the chairman of the League for the Improvement of Marine Park, which throughout its history would have its work cut out for it. In 1925, the City at last made a formal announcement, and Marine Park was born.

The first grand plan for the park came from the turn-of-the-century impresario Sol Bloom, who tried to create a great exposition there to celebrate the two-hundredth anniversary of George Washington’s birth, including a stadium with capacity for two-hundred thousand and a structure tall enough to beam a light that could be seen as far as Detroit. (Like Marine Park, Detroit was spoken of with more hope back then). That version didn’t pan out, but in 1930 six baseball diamonds were unveiled. Then-mayor Jimmy Walker arrived five minutes early, saying confidently, “One day this will be the greatest chain of parks in Greater New York.” Scanning the baseball fields out towards Gerritsen Creek and the homes that had recently been erected, Mayor Walker said, “I hope you will live to see the day when this park is completed. I probably will not. It’s a short life in the mayor’s office, politically and otherwise.” The crowd laughed. In two years Walker would resign in scandal.

Things started to heat up. The first million dollars was appropriated. A contest for park design was announced, then canceled, for the eminent architect Charles Downing Lay had been chosen: he was one of the first to earn a formal degree in the field of landscape architecture and, indeed, a founder of Landscape Architecture magazine. Lay’s design, though not as ridiculous as Bloom’s, was still a whopper: on large, oil-painted canvasses, he dreamed of a park larger than Prospect and Central combined, with a football stadium fit to hold 125,000 people. Also a zoo, a casino, a music grove, an amphitheater, bathing pools, hundreds of tennis courts and baseball diamonds, an eighteen-hole golf course, and slips for hundreds of yachts, as reported by the New York Times—the list goes on.

But the utopian designs for Marine Park ran into an even more titanic midcentury builder: Robert Moses, whose tireless biographer, Robert Caro, has written, “He turned parks, the symbol of man’s quest for serenity and peace, into a source of power.” Mayor Jimmy Walker was no more and these days the “Little Flower,” Fiorello La Guardia, occupied City Hall, and in 1934 (in a move he’d come to regret) he put Moses in sole charge of the city’s newly unified Department of Parks. Lay had the misfortune of crossing the newly-crowned Moses about the importance of decorating all that land along Moses’s beloved roadways (he called parkways “obsolete and ‘ill adapted to present needs,’” as Campanella writes). People just want to get where they’re going, Lay told the king. Drive along the Belt Parkway these days and you’d probably side with Lay, not that public opinion much mattered to Moses. Moses ended up delegating the Marine Park project to one of Lay’s former employees. Thus died the football field.

All this time, the League for the Improvement of Marine Park and their compatriots were doing their best to remain optimistic. In 1931 they were forced to drag themselves down to City Hall to preserve the very name of their park and neighborhood, which was in danger of becoming American Legion Memorial. “If you would go out there and look at Marine Park, you would understand,” a League member said passionately. “You cannot walk there because it is swampy. Anybody who has gone to Marine Park waterways knows that you cannot step on the shore. It is nothing to be proud of.” The name stuck. In 1939, after much to-do, the League got a plaque to commemorate the generosity of Pratt and White, the original donors. That May, the Parks Department band struck up a tune at the unveiling. Moses spoke first, and a League member went second.

Perhaps not understanding the sway of things, a League member wrote to Moses in 1940 asking if it might be a good idea to agitate for the 1944 Olympics to be held in Marine Park. Moses was on a short vacation and a subordinate responded, but the answer was obvious. The only trace of a stadium that would remain was the running and biking track, which exists to this day, surrounded by quiet trees, emptiness inside. Moses had his hands full with the Marine Parkway Bridge and Riis Park (along with the Marine Parkway Authority, moneymakers for Moses), which opened in 1937, and there was no money left for Marine Park. He’d scaled back even his assistant’s scale-back—baseball fields and some tennis courts. In 1936 Downing Lay won a medal for Marine Park’s design at the Berlin Olympics, but the facts on the ground were a done deal. A golf course did get built, it’s true, and some say it’s one of the better ones in the city. But the more salient image, I think, of what happened to the park for the rest of the millennium involved one Bertha Schalk, of Kimball Street, who in 1948 got herself charged with disorderly conduct while forming a human chain across Avenue U at Flatbush Avenue. She hoped to stop garbage trucks from unloading their wares there. In that, at least, Robert Moses and the city government ten miles away begrudgingly obliged.

It’s been a long half-century since then, and despite pamphlets like “Marine Park: Sixty Years of Decay”—printed by Citizens for a Better Brooklyn in 1969—things haven’t changed. “It is common enough knowledge that many middle-class families are fleeing the city for life in the suburbs,” that group wrote archly. “Many groups have succumbed to local rivalries,” the pamphlet states. The park was called the number one “forgotten development” in a postwar edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. But there was never much decay, really. The park just stayed the same.

Photo: Mary Chiusano

Park history, in many ways, repeated itself at the dawn of the new century, when a bathroom and meeting facility was designed to replace the old red-brick structure that used to house the public restrooms, steps from where the entrance to the old football stadium would have been. It took nearly ten years and ran nearly ten million over budget. In the end, residents got a senior center with a green roof and, admittedly, much nicer bathrooms. The politicians trotted out, as in bygone days, and talked about the money they’d raised and the benefits the building would bring. The Marine Park Civic Association was present and saw the building named after a former president of theirs. As usual, people clapped.

But perhaps the senior center was an omen of greater things, albeit in a small way. Today, one can rent bicycles and surreys (who ever saw a surrey in South Brooklyn?) in the parking lot off Avenue U. It’s also possible to rent kayaks, just as you can on the other end of the borough in Brooklyn Bridge Park. You have to pay for them, but what can one expect in this age of austerity we live in? It is just as true as it was in 1930 when an Eagle op-ed said, “In the hot summer days it is many degrees cooler in the Marine Park vicinity than a few blocks away. It seems incredible but is nevertheless a fact.” There are no trains but the buses run well and are clean and orderly. It’s not the Olympics, but then, that wouldn’t be the Marine Park way.

Mark Chiusano is the author of Marine Park, a new collection of stories. His work has appeared in Narrative Magazine, Harvard Review, and online at Tin House and Huffington Post, among other places.

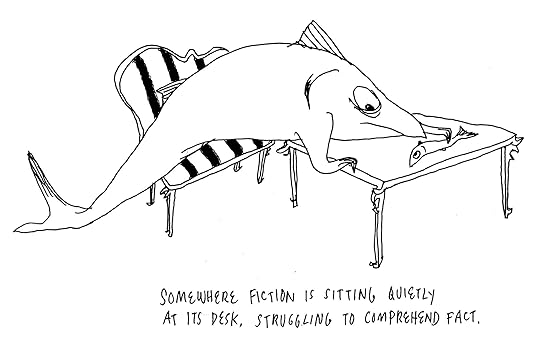

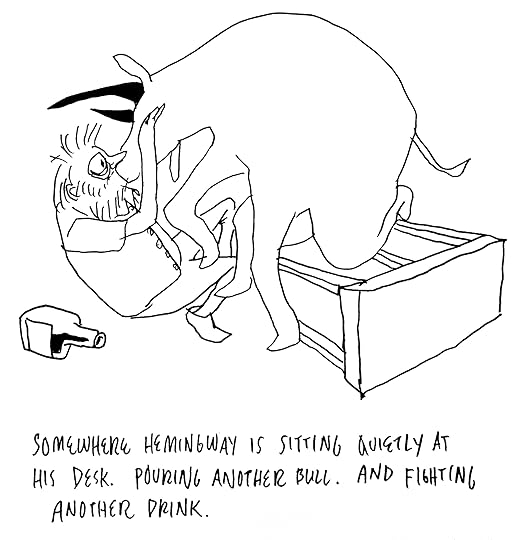

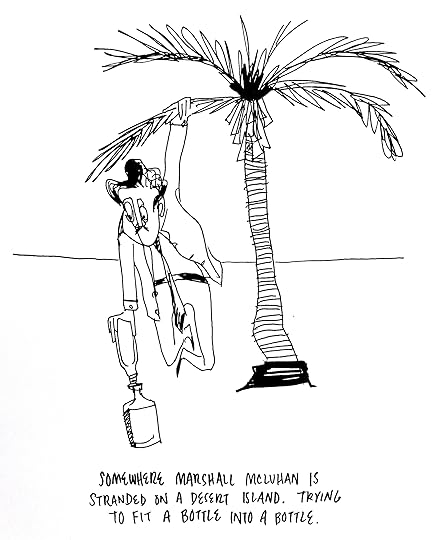

Where Are They Now? Part Four

The fourth in a week-long series of illustrations by Jason Novak, captioned by Eric Jarosinski.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist in Oakland, California.

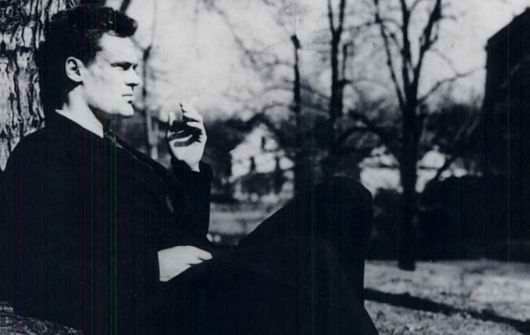

He Killed the Hedgehog, and Other News

Philip Larkin. “His letters to girlfriends were full of little drawings, showing them as cute squirrels or bunnies or honey bears.”

Philip Larkin: Not always a tremendous admirer of people, but an ardent lover of animals. “His secretary Betty Mackereth remembers how, ‘He just stood at the window of his office, looking out, and said: “I mowed the lawn last night; and I killed the hedgehog.” And tears rolled down his face.’ ”

James Meyer, who was for thirty years an assistant of Jasper Johns, has pled guilty to stealing at least twenty-two of Johns’s works—an estimated $6.5 million value.

We live in a world where not one but two new apps promise to re-create “the experience of a manual typewriter, but with the ease and speed of an iPad.”

Against Against: “In recent years, there has been an ‘Against [X]’ epidemic: against young-adult literature, against interpretation, against method, against theory, against epistemology, against happiness, against transparency, against ambience, against heterosexuality, against love, against exercise, et cetera. The form announces a polemic—probably a cranky one, and very likely an unfair one. But an essay with such a title has inoculated itself against the criticism of being too polemical or tendentious—after all, did you read the title? Caveat lector!”

In Pittsburgh, a nonprofit called City of Asylum provides free housing and a stipend “for foreign-born scribes who endured imprisonment, or worse, in their home countries.”

August 27, 2014

Snow Day

Still from Snow White.

Disney’s Snow White is an animation classic, and a beautiful one. But if you’re looking for something altogether weirder (albeit shorter) go back four years, and check out the Fleischer Studios’s 1933 Snow White. Technically, this is a Betty Boop short, and it’s true that the iconic flapper does indeed play “the fairest in the land.” But the cartoon is really a showcase for all kinds of wholly unrelated tricks.

Although it’s technically a “Fleischer Brothers” production, in fact Max and Dave Fleischer didn’t have much to do with Snow White, which is considered the masterpiece of animator Roland Crandall. Apparently Crandall was given free rein on this short as a reward for all his work for the studio, and took full advantage. It’s incredibly innovative, and seriously trippy. This isn’t the only Fleischer Brothers cartoon to employ the voice talents of bandleader Cab Calloway, or even his rotoscoped moves (he also cameoed as the Old Man of the Mountain), but it’s the best: as Koko the Clown, and then a ghost, Calloway does a haunting rendition of the “St. James Infirmary Blues,” and then what might be the first recorded instance of the moonwalk. What does any of this have to do with the story of Snow White? Not all that much. But that’s what Disney was for.

(To see the full seven-minute version, click here.)

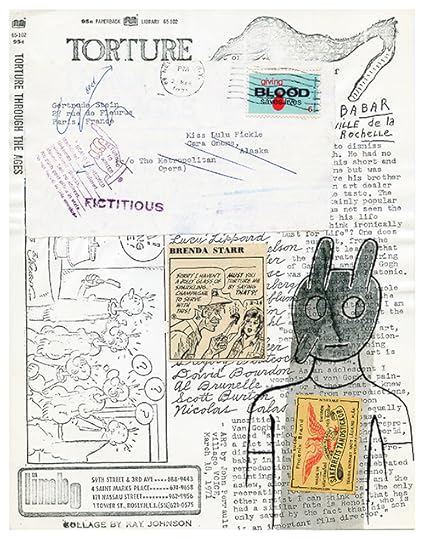

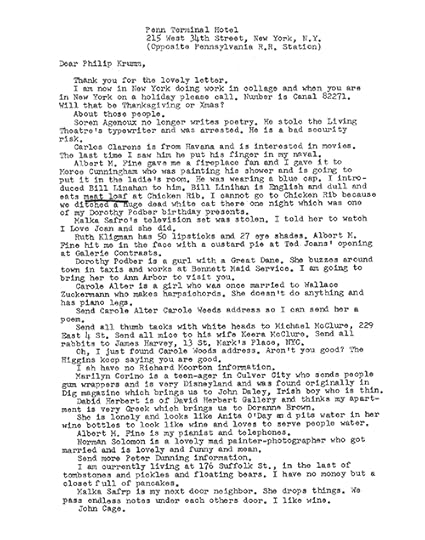

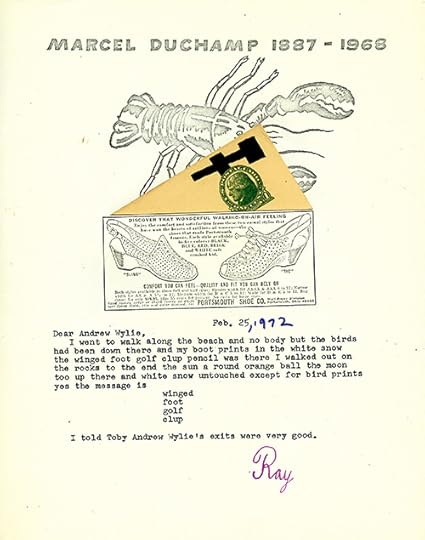

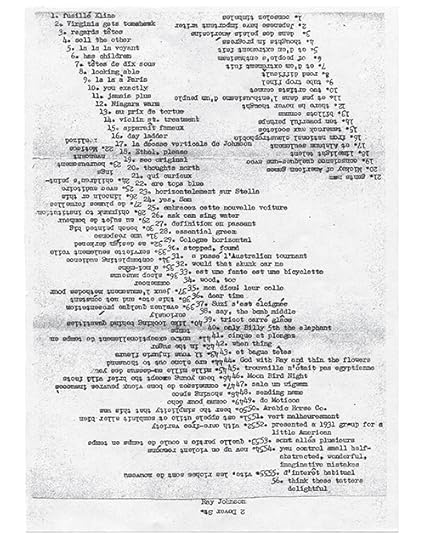

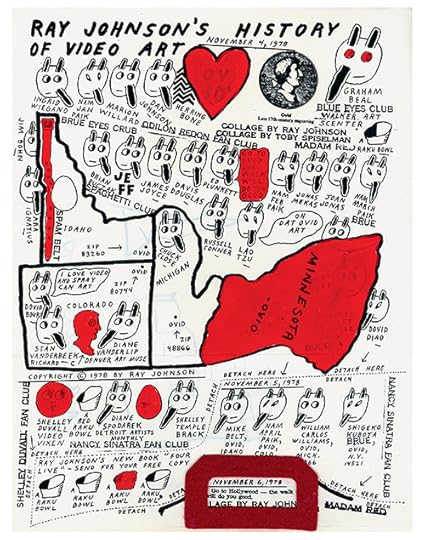

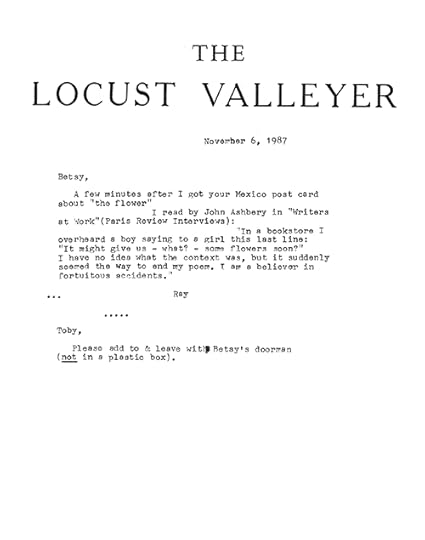

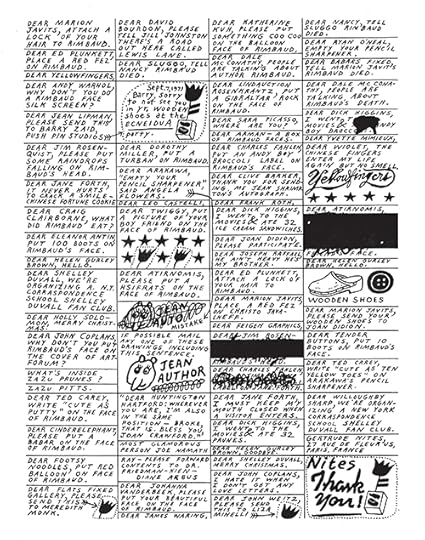

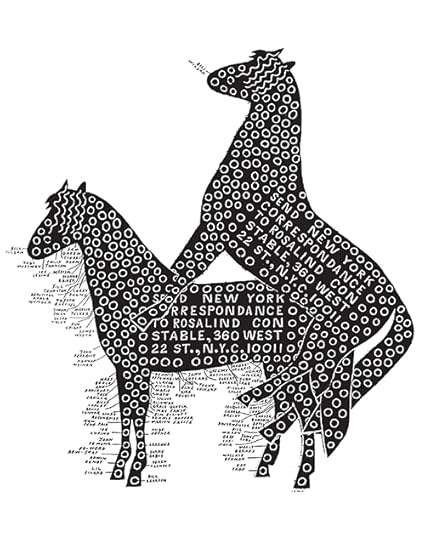

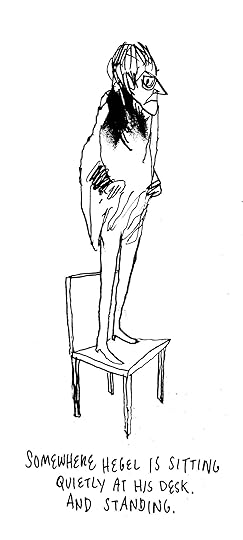

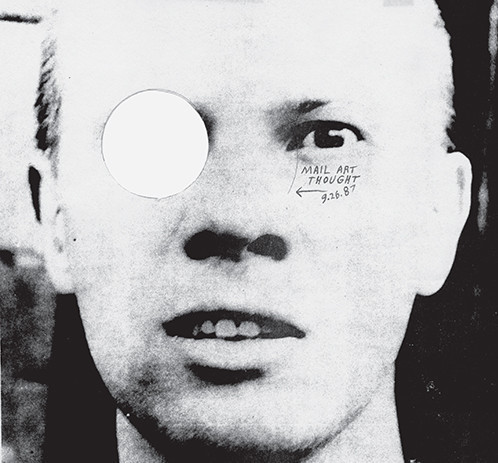

Please Forward Contents

Remembering Ray Johnson through his pioneering correspondence art.

Detail of a work from Not Nothing: Selected Writings, 1954–1994, published by Siglio.

Ray Johnson thought he was ugly, but I thought he looked cool—just like Ray Johnson.

Being a teenage modern-art fan in Texas in the sixties, I was excited to learn of the New York Correspondence School from Eye magazine, or maybe it was Artforum or Print. Ray, whose early abstracted celebrity photos and painted collages I had seen featured in the pages of many histories of Pop, was encouraging artists all over the world to make and trade mail as an art activity, an idea readily appreciated in the midcentury’s burst of experimental and novel art approaches. Thousands of people began to send art objects to each other through the postal service.

My notion was that Ray didn’t make the first piece of mail art, but his creation of a school around that activity was the benediction for a folk-art movement in motion. Some of these letters were finished statements or handmade objects; others were exquisite corpses conducted by mail, objects that traveled and accumulated the mojo of human touch and attention as they were ever modified. The latter was the kind of thing Ray did: he mailed objects and letters and asked the recipients to add to them and then return them, or send them along to other destinations. Ray’s handmade work, cryptic and rarely seen, was striking, sure, but humorous, too, a quality I really like in art. It had a purposive childishness, but also a readily appreciable design rigor—a controlled looseness, beautiful color, shape and textural sense, a mastery of a private hieroglyphics of bunnies and goo-goo eyes.

I see in the work of Dubuffet, Dine, Oldenburg, Hockney, Red Grooms, and the avant-garde Cobra group a self-conscious reversion to childhood artistic approaches and enthusiasms as a starting point for self-investigation. It can be helpful, and maybe essential, for artists to relearn the freedom and work of child's play and to unlearn and strip away the imposed habits, expectations, and limitations of received culture. The aforementioned artists were marked by the twentieth century's World Wars and economic depression; the culture needed some lightening up. Mail art was an art form everyone had access to. It developed before the computer age and even before high-quality photocopies; artists young and old could join the conversation, as could people in far-flung places.

I wrote Ray Johnson a fan letter on lined grade-school paper in 1970, and I am glad he didn’t remember receiving it when he called me up in the late eighties, and blew my fanboy mind by doing so. I had learned by that time what an influence Ray was on other artists and on the temper of the time and the chemistry of the transition from the black-and-white, suited, crew-cut fifties to the colorful, frantic, long-haired sixties. He was a major alchemist, employing the power of the small, personal gesture.

Maybe he called me because he was a fan of Pee-wee Herman. He mailed me a big Diesel jeans box, from which he had cut sections of cardboard, and asked me to send it to Paul Reubens, with instruction for Paul. I phoned Paul and told him it was important and valuable and that he should play along with the instructions and modify the box and mail it back to Ray, but I imagine that Paul was too busy being a movie star, which would have been one of the reasons Ray was interested in him in the first place. Another was that the Pee-wee character was a nerd misfit, and Ray seemed to reject his own lot; he thought himself a misfit and an outsider and kept it that way as a routine or policy or public persona. Moving his studio to Long Island and playing complicated games with collectors and curators kept people at a remove and kept Ray alone in the house making a lot of beautiful art objects, and puzzling ones, too.

He knew my work, though, and I was pretty swell-headed and happy about that. I asked him the first time he called if he was painting, which was an inexact way to begin to ask him about his long, complicated process of collage. He said, Let me put it this way, this morning I was out in the yard and there was a beautiful woodpecker on the roof, so I ran to get my camera and a ladder and by the time I got back, the woodpecker was gone, so I set up the ladder and climbed up and took a picture of the roof where the bird had been.

I said that it sounded to me like he was painting.

Ray never gave me his phone number, but he called out of the blue four or five times. I told him that he had a very young-sounding voice, and he said that he hated his looks and that he was old. He sent me a few photocopies with marks or stamps affixed to them and instructions to add to them and forward to people I didn’t know, all of which I did.

As a typical fan would inevitably do, I asked him to contribute to an underground comic, which never did see the light of day. I had asked a lot of people, and many sent me work in vain, little did they know. Little did I know. Ray sent me a photocopy of a traced profile of de Kooning ornamented with bunny stamps. A month or so later, Ray made his calculated and tragic and majestic and pitiful exit from this world, our world, where you can still make collages, tease friends, and wave to the postman.

Gary Panter is a painter, cartoonist, and designer. His exhibition of new work will be on view at Fredericks & Freiser, in New York, from August 26 through September 27.

All images from Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994 . Copyright the Estate of Ray Johnson, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co.

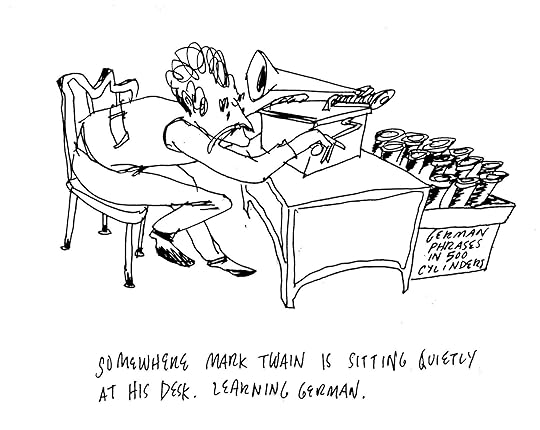

Where Are They Now? Part Three

The third in a week-long series of illustrations by Jason Novak, captioned by Eric Jarosinski.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Eric Jarosinski is the editor of Nein Quarterly.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist in Oakland, California.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers