The Paris Review's Blog, page 665

September 9, 2014

The Words Are Everything

Our congratulations to Ursula K. Le Guin, who will receive the National Book Foundation’s 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters:

“Ursula Le Guin has had an extraordinary impact on several generations of readers and, particularly, writers in the United States and around the world,” said Harold Augenbraum, the Foundation’s Executive Director. “She has shown how great writing will obliterate the antiquated—and never really valid—line between popular and literary art. Her influence will be felt for decades to come.”

And additional congratulations are in order for Louise Erdrich, who has won the PEN/Saul Bellow Award, a “lifetime achievement honor for American writers” judged this year by E. L. Doctorow, Zadie Smith, and Edwidge Danticat, “who praised the ‘awesome’ breadth of Erdrich’s work.”

The Paris Review has interviewed both Le Guin and Erdrich for our Art of Fiction series, the former in 2013 and the latter in 2010. Erdrich advised aspiring writers,

Begin with something in your range. Then write it as a secret. I’d be paralyzed if I thought I had to write a great novel, and no matter how good I think a book is on one day, I know now that a time will come when I will look upon it as a failure. The gratification has to come from the effort itself. I try not to look back. I approach the work as though, in truth, I’m nothing and the words are everything. Then I write to save my life. If you are a writer, that will be true. Writing has saved my life.

And Le Guin said,

Fiction is something that only human beings do, and only in certain circumstances. We don’t know exactly for what purposes. But one of the things it does is lead you to recognize what you did not know before … A very good book tells me news, tells me things I didn’t know, or didn’t know I knew, yet I recognize them—yes, I see, yes, this is how the world is. Fiction—and poetry and drama—cleanse the doors of perception. All the arts do this. Music, painting, dance say for us what can’t be said in words. But the mystery of literature is that it does say it in words, often straightforward ones.

We offer both of them our best wishes.

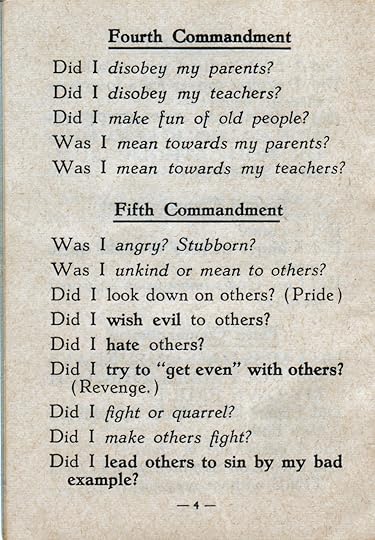

Conscience for Boys and Girls

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853

Scrolling through Retronaut, you might run across a 1927 pamphlet called “Examination of Conscience for Boys and Girls,” which the site resurfaced last year. It’s a Catholic publication by a Jesuit brother named A.J. Wilwerding, distributed by something called “The Queen’s Work” in Saint Louis. The first few pages are pretty straightforward—the author defines different kinds of sins and helpfully distinguishes them by typeface: venial, venial (at risk of becoming Mortal), and MORTAL. Did the child DENY he was a Catholic? Did he curse? Did he misbehave in church? And then you reach the fourth page:

And maybe you cry, and you think that these are not bad rules to live by. Not just for kids. Certainly not just for Catholics. And that it’s not easy; as Morrissey said, it takes guts.

Of course, then you keep reading:

DID I WILLINGLY TAKE PLEASURE IN USING IMPURE WORDS?

DID I WILLINGLY TELL IMPURE STORIES AND TAKE PLEASURE IN THEM?

DID I LIKE TO LISTEN TO IMPURE THOUGHTS?

DID I TAKE PLEASURE IN SINGING IMPURE SONGS?

DID I WANT IMPURE THOUGHTS AND DID I TAKE PLEASURE IN THEM?

DID I TEACH OTHERS TO COMMIT IMPURE SINS?

DID I TAKE PLEASURE IN TOUCHING MYSELF OR OTHERS IN AN IMPURE MANNER, OR LET OTHERS DO SO TO ME?

DID I COMMIT AN IMPURE ACT?

DID I REALLY WANT TO LOOK AT IMPURE THINGS OR PICTURES?

This is a relief.

That’s better, you might think. That’s imposed enough distance and history and sadness on the whole thing. Irony, or contempt, even. Easier to forget that one page, I think. Probably all of it. Although I do rather like the notion that italics are a venial sin.

Regarding Mystery: An Interview with Richard Rodriguez

Photo: Timothy Archibald

In San Francisco earlier this spring, I’d hoped to meet the essayist Richard Rodriguez, the author of The Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez, Days of Obligation: An Argument with My Mexican Father, Brown: The Last Discovery of America, and, most recently, Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography, which has just been published in paperback. Though he’s largely associated with his early stances against affirmative action and bilingual education, not to mention his regular appearances on the PBS NewsHour, Rodriguez, who turned seventy in July, has had a wide-ranging career, and I wanted to discuss the shift of his work from cultural identity to religion. But our schedules were tricky to coordinate, and then I lost my wallet. “Pray to St. Anthony!” Rodriguez immediately wrote. (The wallet was recovered by one of the famous bellmen at Sir Francis Drake Hotel. “St. Anthony dressed as a beefeater,” as Rodriguez put it.) Instead, we corresponded for several weeks.

I was excited and surprised by Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography. I had seen you referred to as a Mexican-American writer, a Californian writer, and a gay writer, but never, until recently, as a religious writer. Have you always considered yourself a religious writer?

Of course, I haven’t, until lately, considered myself a “writer”—in the grand sense. For most of my writing life, I have stood truly, if uneasily, on American bookstore shelves as a sociological sample—shelved “Latino” between a gangbanger’s book of poetry and the biography of a Colombian drug lord. Only in recent years, as it has become clear to me that so few people I know read books, have I been struck by the fact that I am a writer.

My sense of being religious is older. From boyhood, particularly my lower-middle-class childhood in Sacramento, I was transported by religion into the realm of mystery. Consider this: The Irish nun excused me from arithmetic class so that I could serve as an altar boy at a funeral mass. Along with the priest and the other altar boy, I would welcome Death at the doors of the church. We escorted Death up the main aisle. I later went with the cortege to the cemetery. There was a fresh pile of soil piled high at the edge of the grave site, discreetly, if unsuccessfully, covered by an AstroTurf rug that was as unconvincing a denial of the hardness of time as a cheap toupee. I wondered at the mourners’ faces—the melting grief, the hard stoicism. Thirty minutes from the grave, I was back within the soft green walls of Sacred Heart Parish School. It was almost lunchtime. I resumed my impersonation of an American kid.

Were there certain writers that you looked to in forming your style? Sometimes I sense a bit of Auden coming through.

As a reader, I knew Auden the poet many years before I knew Auden the essayist. I don’t know quite how to say this, but I find him gloriously un-modern because of his religious faith. There is a strength in his essays, some bedrock, that makes him seem, in the best sense, Victorian. He doesn’t go all wobbly as a modern might.

My earliest influences in the art of the personal essay were more local. There was Joan Didion—the Didion of those glorious California essays of the sixties. Because she was from Sacramento and writing about the Central Valley when I first read her, it was she who taught me to imagine my own Sacramento as a literary landscape. About that same time, there was William Saroyan. There were voices in Saroyan, particularly the wondering boy in Fresno and the hungry writer’s voice in San Francisco, I have never forgotten. For all of the passion and energy in Saroyan, however, there was something sexless about him—the son of a Presbyterian minister. Maybe that sexual diffidence deepened my sense of companionship with him. For reasons of my own, I did not, for many years, imagine sex in my writing.

I should mention two other influences crucial for my appreciation of the personal essay. First, James Baldwin, the great Jimmy Baldwin. I began with Nobody Knows My Name and I never let go of him—through the years of the Negro Civil Rights movement on our small black-and-white TV, then the many decades after. What impressed me about Baldwin was his literary elegance, despite all. He was never more resolutely in control than when he was describing Jim Crow America. The hideousness of anti-black racism could not undermine the clean line of his prose. And Orwell! I learned from George Orwell that narrative was compatible with the essay, that it was possible to write what I call the “biography of an idea”—and trace the way an idea makes its way through a life. Beginning with my first book and in all the books after, I employed the fictional devices of the short-story writer in writing my essays. My best essays, I think, are unafraid to be stories. That’s Orwell’s influence.

In another interview, you talk about experiencing what Auden, in his essay “The Protestant Mystics,” called a Vision of Agape, when you were undergoing surgery for kidney cancer.

In another interview, you talk about experiencing what Auden, in his essay “The Protestant Mystics,” called a Vision of Agape, when you were undergoing surgery for kidney cancer.

I mention in Darling that the night my mother died, the floor lamp at the foot of my bed turned itself on. When I told this to a neighbor, he supposed there must have been some sort of power surge in our part of the city.

Maybe because as a writer and journalist I live in a prosaic society, I long ago learned a certain discretion regarding mystery, one not enforced against poets like Auden. If Jesus ever appeared to me, as He appeared to Reynolds Price, I would not mention it here.

All I will tell you is that one summer dawn, in a dark pre-op room at St. Mary’s Hospital in San Francisco, in the minutes before my gurney was wheeled into the operating room where I would be separated from a two-inch blue-gray tumor, I experienced something—let me call it a sense of peace. This was all pre-anesthesia. Something happened to me—passive construction. From whence it came, I cannot say. I remember feeling something like a warm rush of water over my body. I did not levitate but I came close to the joyful lightness of being that the astronaut freed of gravity enjoys. This exhilaration lasted for no more than a minute. And it took place under a sentimental statue of the Virgin Mary, holding the Baby Jesus. When a Mexican male nurse who looked strangely like me—of the same age and toothy smile—pushed my gurney into the surgery, he softly told me, his face upside down over my head, that he had survived the same operation, and that I must not worry. I felt giddy. I smiled almost to laughter when I shook the lead surgeon’s hand.

The desert appears often in Darling. I appreciated your take on it as a somehow fertile place. I had come to associate it with boredom and acedia, the noonday demon, about which the desert monastics used to complain.

I long regarded the desert ecology with a curiosity I gave to no other landscape. In a dentist’s waiting room, as a boy, I stopped attending to the shrieking drill behind the pebbled glass window when I beheld photographs of the North African desert in National Geographic. My interest was as strange to me as sexual desire. I had no name for what attracted me.

I love the semantic paradox proposed by the noun we give to the desert—a place we define by what is no longer there. Once there were seas, once great tribes crossed these plains, great flocks of animals, once angels were as common as herons.

Place is always central to the writing of an essay for me, because we live in our bodies and whatever we know comes within the experience of our bodies. When I started thinking about the desert religions, I was struck by how rooted in place they are. I consider acedia to be the thorniest flower of the desert. Acedia is, on the one hand, the midday loneliness the monks find burdensome. But it also opens the soul to a longing for the solitary God who yearns for us. I do not mean to imply a deterministic interpretation of religion, but I cannot write of the Abrahamic religions without writing of the desert.

And yes, I write of “postlapsarian” California, where I live. I write of the decline of my local newspaper. In writing about dying newspapers, I end up noticing the decline of the American cemetery, as more and more Americans are being cremated and their ashes are cast to the wind. And look at those boys and girls of modernity, along with their crazed parents and grandparents, walking up Fillmore Street, consulting their digital toys of “communication,” oblivious to my staring. Much of the satire in Darling is directed against the modern secular resistance to place.

Las Vegas! Look at the way Las Vegas amuses the visitor by toying with the desert’s tragic conclusion. Las Vegas has even become a model for the oil-rich capitals of the Middle East with their ice palaces and golf courses and skyscrapers that stand defiantly vertical against the desert’s horizontal plane. Even Mecca has lately constructed a vast shopping center and a hotel in the shape of Big Ben, dwarfing the Kaaba.

The task of living within our bodies, even more than the fear of leaving the body in death, may be our greatest human predicament.

What does your average day, living in your body, look like?

My own writing life is as predictable as the old priest preparing to say the dawn mass. The pleasant cold, the mild pain of being alive. I have the same breakfast every day—cold cereal, yogurt, coffee. I read the newspapers. I take a fistful of vitamins. I shower. I linger at my bookshelf or at the window. I read a chapter or a poem from a shelf I keep above my desk of former lovers and seducers, impossible rivals—Nabokov or Lawrence, Larkin. Woolf. Sitting down at the computer is as daunting as the altar boy’s first genuflection.

Aquinas described writing as a form of prayer. Writing is for me dishearteningly hermetic. Revision is writing. Revision is humiliation—Tuesday saying something less well than Monday. Revision is open to noticing connections. Revision is joy at precisely that moment when the sentence no longer seems mine but speaks back to me and haughtily resists further revision.

I read in the afternoons. I take long walks. I watch TV in the evening. I write letters at all times.

Do you have any advice for younger writers hoping for a career?

I don’t have any advice. You are asking me to live in an era other than the one that formed me. But I will tell you this: An editor in New York told me the other day that, even as the reading audience for serious prose has diminished, the unsolicited manuscripts she receives are better than ever. Even while I think we are leaving the splendid Victorian age of serious popular literature—novels and poetry—we may be entering the Elizabethan Age, when few in London read, but there was an intensity of thought and beauty to the prose, and the poetry, and, of course, the plays.

Religion still reveres the book—just visit a yeshiva if you want to see devotion to the weight of the holy word. But in our secular lives the digital revolution seems to have eroded the great age of the middle-class reader. And without readers what are we? Half-writers whose sentences are never completed by the stranger’s eyes.

I tell young writers not to give a single sentence away. Charge for every noun! Beyond the matter of strategy, the question really is whether our society needs complicated thought or expressions of beauty that reveal themselves only slowly and with difficulty. The question is whether a civilization can forget the pleasure of difficult, beautiful writing so thoroughly as to ignore its loss.

David Michael is a writer and producer living in Brooklyn.

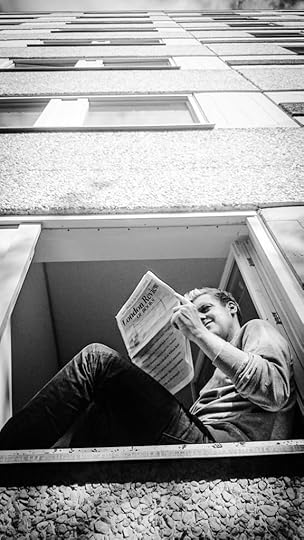

Our Globe-trotting Winners

Last month’s #ReadEverywhere contest was a great success. (If you need a refresher: we asked readers to submit pictures of themselves reading The Paris Review or The London Review of Books around the world.) Now the time has come to announce the winners. Cue the marching band, please, and have the sommeliers ready their champagne sabers …

THIRD PLACE is a tie! Both Ivan Herrera and Anders Gäddlin will receive third-place prizes. Ivan is pictured with The Paris Review (and an erumpent sparkler) at Tennessee Alabama Fireworks. Anders read The London Review of Books in a “modernist twentieth-century utopian suburb”: Råslätt, Jönköping, Sweden. They’ll get a copy of one of our Writers at Work anthologies and an LRB mug.

Ivan Herrera

Anders Gäddlin

SECOND PLACE goes to @arodchenko, who keeps bees on Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal; she and her beekeeping partner “read everywhere, even while checking our hives!” Her prizes: a full-color poster of Helen Frankenthaler’s West Wind, part of TPR’s print series; and two books of entries from the LRB’s famed personals section, They Call Me Naughty Lola and Sexually, I’m More of a Switzerland.

@arodchenko

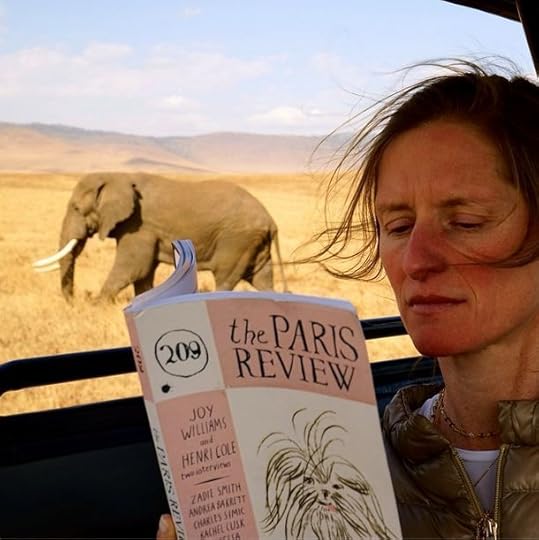

And FIRST PLACE is awarded to David Lasry, who somehow coaxed a pelican in Mahale, Tanzania into attempting to eat The Paris Review’s Summer issue. (Note that the issue matches the bird.) From The Paris Review, David will receive one vintage issue from every decade we’ve been around—that’s seven issues, total—curated by our editor, Lorin Stein. And from The London Review of Books: A copy of Peter Campbell’s Artwork and an LRB cover print.

David Lasry

HONORABLE MENTIONS go to Jim Carey, who read The London Review of Books while floating on the Dead Sea; and Evelyn Day Lasry, who read The Paris Review within eyeshot of an elephant.

Jim Carey

Evelyn Day Lasry

Congratulations to our winners, and many thanks to everyone who contributed! You can see a map of all the submissions here.

More Than Mere Brotherly Love, and Other News

Nicolaus Knüpfer, Bordeelscène, ca. 1650.

If you were a rake headed to Philly in the 1840s, you wanted to have this pocket guide with you—it lists all the brothels in town, with some helpful editorializing about each. “None but gentlemen visit this Paradise of Love,” one description says. Another: “Beware of this house, stranger, as you would the sting of a viper.”

A list of the one hundred most popular books on Facebook contains exactly zero surprises.

From a new documentary on Susan Sontag: “She sat me down on her bed … and ran through the argument of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. She must have been fifteen.”

“We all have bodies; we all wear clothes; we all have reflections that vex us; we all exist in dynamic relationship to our communities, and fashion is a medium for testing or strengthening those bonds … anyone who diminishes the significance of that is carrying water for the patriarchy, deferring reflexively to those thousands of years of human history when men got to decide what was frivolous or not. You know what's frivolous? Fantasy football.”

In 1932, Einstein endorsed a psychic. And she endorsed him: “Dr. Einstein is indeed the most remarkable personality I have ever contacted [sic]. And his aura is just sublime—pure blue electric sparks, instead of color. It was just like talking to God.” And so Einstein’s credibility as a scientist came under fire: “Now he is the tamest lion in the intellectual zoo. He goes everywhere. He attends picture openings with the regularity and aplomb of Clark Gable. He is at all the public dinners.”

September 8, 2014

Tomorrow: Robyn Creswell at NYU

Image via Bidoun

Tuesday evening at seven, join us at NYU’s Abu Dhabi Institute (19 Washington Square North) where our poetry editor, Robyn Creswell, will appear on a panel called “The Authoritarian Turn: On The State of the Egyptian Intelligentsia.” The panel, sponsored by New Directions and Bidoun, will

bring together a distinguished group of writers and scholars to reflect upon the predicament of the Egyptian intellectual in the year since President Mohamed Morsi’s dramatic fall. From Ibrahim himself to the bestselling author Alaa Al Aswany, countless writers and artists–many of them of historically contrarian bent–have expressed their support for a military-backed government whose abuses and excesses have on occasion surpassed those of the Mubarak era. How to begin to understand the role of the public intellectual in such times?

Robyn appears alongside Khaled Fahmy (American University in Cairo) and Mona El Ghobashy (an independent scholar); Negar Azimi moderates.

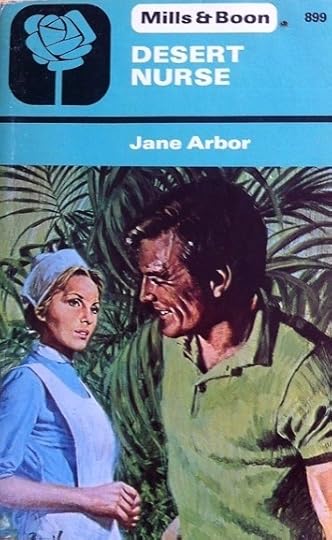

Strong Names

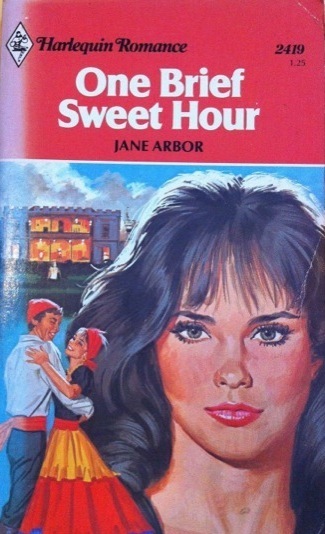

Sometimes you go to Wikipedia to see whose birthday it is and you end up spending the next thirty minutes reading flap copy from old Harlequin romances. By “you” I mean me, here—I’ve just now crawled up out of the Jane Arbor mineshaft I fell into.

Arbor, who was, yes, born today in 1903, wrote fifty-seven romance novels in her day, all of them published by Mills & Boon, a UK imprint of Harlequin. Even without their florid illustrations, their titles are terrific; they sound variously like managerial concepts, short-lived sitcoms, or Yankee Candle scents. In addition to those in the slideshow above, here are a few favorites:

Ladder of Understanding (1949)

My Surgeon Neighbor (1950)

Memory Serves My Love (1952)

Jasmine Harvest (1963)

The Feathered Shaft (1970)

Two Pins in a Fountain (1977)

But Arbor’s true talent was in naming her characters, a gift that extended to the author herself. Jane Arbor is a pseudonym—and a pretty perfect one, dainty without lacking in heft and authority—for the comparatively ungainly Eileen Norah Owbridge. Arbor had a knack for naming her heroines’ love interests, all of whom have strong but subtle appellations of three or four syllables. They’re impossibly perfect names that seem hewn from granite, as are, presumably, the abdomens of the men they belong to. Names like Erie Nash. Dale Ransome. Elyot Vance. Lewis Craig. Mark Triton. Raoul Leduc. Grandmere Cordet. You see how a Piepenbring could be envious.

Without further prologue, then: the flap copy for three of Arbor’s novels.

The Growing Moon:

Cesare Vidal’s attitude left Dinah silently fuming. He’d shifted responsibility for the twins to her shoulders and apparently had no interest in them—even though they were his cousins.

Maybe she should have been flattered, but she would have gladly exchanged his airy confidence in her for a little old-fashioned male concern. Why couldn’t she be given a trace of the solicitude he showed for Princess Francia Lagna?

One Brief Sweet Hour:

The luxurious Caribbean cruise was a onetime extravagance—supposed to help Lauren forget the past and build a new life.

Instead it brought her face to face with the unhappiest part of that past—Dale Ransome. He was as bitter and hurtful as ever.

All Lauren wanted to do then was return home—but she stayed to help Dale’s young brother with a problem. She never dreamed it would help solve her own!

Roman Summer:

Teaching an attractive teenager to love Rome didn’t seem a particularly arduous job. But for Ruth it meant having to fight her old attraction to Erie Nash, who had said, “The folly of marriage is a heady, distracting adventure I don't mean to afford.”

Border Control

The queue for customs was long, and very disorganized. People kept trying to cut—or they cut inadvertently, and were yelled at. But really, it was hard to tell what was a line, and who was in charge, and what they wanted from you. You could only do wrong. It was like being a child in a Roald Dahl story, arbitrary and potentially magical, if you are in the business of silver linings.

And then suddenly a new officer appeared. He didn’t seem to be standing anywhere official, exactly; I mean, there were no dividers or ropes or podium sorts of things around him. He had just chosen an arbitrary spot kind of near the exit. But he was wearing a uniform and radiated great authority. “New Line!” he shouted. “I AM A LINE!”

I was pondering what it meant to be a line—I was very tired—when he beckoned me forward. “Now!” he barked. And then, “STAY BACK. DO NOT RUSH FORWARD.” And then, “IF YOU HOARD ME, I WILL LEAVE.”

“If you hoard me / I will leave.”

Or maybe:

if you hoard me

i will leave

Even,

if you

hoard

me

i will leave

“MOVE!” he shouted.

But I am hoarding him now.

Forever

And ever. Has he left?

Welcome

Home.

Pastless Futureless Man

Image: Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator

“The Marivaudian being is, according to Poulet, a pastless futureless man, born anew at every instant. The instants are points which organize themselves into a line, but what is important is the instant, not the line. The Marivaudian being has in a sense no history. Nothing follows from what has gone before. He is constantly surprised. He cannot predict his own reaction to events. He is constantly being overtaken by events. A condition of breathlessness and dazzlement surrounds him. In consequence he exists in a certain freshness which seems, if I may so, very desirable.”

—Donald Barthelme, “Robert Kennedy Saved from Drowning”

I’ve been watching and avoiding a man who lives in the present. We go to the same café, each of us alone. He resembles a distinguished physicist, the kind invited to appear on television when a scientific worldview is needed. So I was intent on listening to him when he stood up to greet his friend, also in his golden years.

The friend asked him how he had been doing.

“Oh, I don’t know, I misplaced my laptop. I can’t remember where I put it.”

“Did you ask someone for help?”

“I think so. But you know I can’t remember anything. And so I bought an iPad, but I lost that, too.”

“Yes, I lost my car the other day.”

“No. Where?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t remember anything?”

“No.”

“I see. I don’t, either.”

What united these two seemed to be kindness and an ability to chat ad infinitum about everything they couldn’t remember. They mentioned the failure of their memories more times than seemed possible.

“Has your family visited?”

“I don’t know. I don’t remember. How about you?”

“Yeah. Hard to say. That’s not something I remember.”

It was kind of like a first date. They would get to the subject of movies only to realize neither could say anything specific. “I think I saw that one. But, you know, I don’t really remember anything.”

“Yes, I know. I don’t remember anything either. But I think it won an Academy Award.”

“I don’t know. I don’t remember. Let me check.” The friend reached for his phone. “No, it was only a Golden Globe.”

And for an hour I listened.

One of the worst ideas to emerge since yoga and Buddhism came in vogue is how you ought to live in the present. Celebs hurried to the cause, which should have been fair warning for the rest of us to sprint in the other direction. Happiness exists only in the moment, we’re told, in mindfulness, in attaining complete presence.

Here was one such presence.

Sometimes our schedules coincide. This pastless man orders the same cup of coffee every time, carrying an Economist or a book of history from the library. How he decided on a title was something that interested the Walter Benjamin in me. With time I started to imagine that someone chose for him.

Often he falls asleep.

One day a salesman sharing my table lit up when the man walked in. “Hey hey,” the salesman said, immediately.

I felt ashamed for having never said anything to the man, despite having sat across from him dozens of times. But perhaps it isn’t rude if he has no memory of it.

The salesmen extended his hand. “I wanted to say hi. But I’m sorry, I forgot your name. I’m Brian.”

Of all the things to say, bringing up forgetting like that. It couldn’t have been more perfect. The effect was electrifying. Perhaps the salesman has a sadistic streak, and often introduces himself this way to my subject, living out his version of Groundhog Day.

The man with no memory paused, adding to the suspense.

“You know, I’m so sorry, but you might remember I don’t remember anything.”

And he didn’t say his name. He only met the guy’s hand.

“How have you been?” the salesman continued.

“Not bad,” the man said. I wondered how he decided what to say to that question. “I lost three iPads and two computers this year. I can’t find anything. It’s terrible. I can’t remember what happened. I put things down and then I lose them.”

Their conversation stalled there, on these missing computers he’s always bringing up. The man went back to his coffee and the moldy tome on Churchill’s wife. Why does he read, given that he’s only going to forget it? It must satisfy some present moment in him, or it’s a way to pass the time. The memoryless man started to fiddle with his iPhone. He leaned over to the salesman: “I don’t mean to bother you, but I wonder if I can use this to get on those WWW places.”

“The Internet?”

“Yeah, that.”

“Of course, yes, that’s what it’s for.”

“Great, but I forget how. Can you help me? How can I get my e-mail?”

The salesman examined the man’s iPhone. “Well, you’ll need your password.”

A look of doom passed over him, as if to say, Wow, I have to remember that, too. The burden of it all, trying to keep up. He had no idea what the password was, and he didn’t remember that he’d gone through this same conversation with someone else an hour earlier. He put away his phone, stared out the window, yawned. Sipped his coffee. Eventually he picked the phone up again and shuffled through the various app windows, not opening any. He’d mastered the act of swiping, at least.

He has an umbrella. There’s a drought on in LA. Someone takes great care of him, I assume. Hats off to you. Appearing bored, he opened his book, where there was a bookmark reminding him where he left off. Clever. You could put it in another spot and he wouldn’t notice. You could change the book, for that matter.

Leaning forward, he mumbled to himself as he read, but I couldn’t make out his lips. He stared at the page as if he were reading. I know what reading looks like, and I’d bet my house he wasn’t really reading. He’d stop, cover his mouth as if deep in thought, look around the café, and then scan the same paragraph again, this professorial man. He moved the bookmark out of the way as if he were going to continue on to the opposite page, but he didn’t.

Over the months, I’ve continued to study him. With time there came the new laptop with passwords scribbled on a sticker by the trackpad. The last time I saw him, with my phone still on the table, he looked up at me with great horror. Please, don’t forget that, his whole face said.

Bernard Radfar is the author of Mecca Pimp: A Novel of Love and Human Trafficking and Insincerely Yours: Letters from a Prankster. Two of his screenplays are currently in development. Follow him on Twitter.

Smoke This Book, and Other News

The novelist Martha Baillie turned her book into installation art. Photo via Publishers Weekly

In praise of the footnote1: “Many readers, and perhaps some publishers, seem to view endnotes, indexes, and the like as gratuitous dressing—the literary equivalent of purple kale leaves at the edges of the crudités platter. You put them there to round out and dignify the main text, but they’re too raw to digest, and often stiff … Still, the back matter is not simply a garnish. Indexes open a text up. Notes are often integral to meaning, and, occasionally, they’re beautiful, too.”

One way of arguing for the necessity of print: “Rather than stand on a street corner yelling, ‘Literature is not commodity!’ I decided to inflict a series of physical experiments on my published work, to take several copies of the new book, go at them with my hands, and see what might result. I stripped the book of its cover, bought a pouch of tobacco, tore the pages, rolled the words.”

Among the many treasures of the Bodleian Libraries: “A bivalve locket with locks of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s hair. ‘Blessed are the eyes that saw him alive,’ an inscription reads in Latin.”

“Metaphor is actually a fundamental constituent of language … In the seemingly literal statement ‘He’s out of sight,’ the visual field is metaphorized as a container that holds things … Ordinary language is saturated with metaphors. Our eyes point to where we’re going, so we tend to speak of future time as being ‘ahead’ of us. When things increase, they tend to go up relative to us, so we tend to speak of stocks ‘rising’ instead of getting more expensive.”

Really, though, if humanity discovered evidence of extraterrestrial life, could we be expected to behave ourselves? “There might be happiness and celebration to mark the end of isolation, or the news might be met with a shrug. But human nature suggests it’s more probable that this discovery triggers a chain of events that lead to utter disaster. Suddenly your safe haven is threatened by an unknown ‘them.’ Your time-tested principles of governance and social order are put under pressure. Gossip, rumor, and conjecture will gnaw away at your stable home.”

1. And the endnote, too.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers