The Paris Review's Blog, page 662

September 18, 2014

Antrim Returns, and Other News

John Jeremiah Sullivan on Donald Antrim and his new collection of short stories, The Emerald Light in the Air: “That last story [‘The Emerald Light’] does something special, something very quiet that demands extremely close brushwork, something that exceedingly few writers can do … The technique is one of illusion and happens at the level of the text itself. It’s a way of rendering permeable the surface lens that divides the underworld of fantasy from the ‘painful realism’ hovering above it, so that writer and reader at moments seem joined in not being totally certain whether what’s happening on the page should be taken literally and naturalistically or as mythical, otherworldly.”

“It is almost unheard-of for the same writer to have a byline on the lead item in rival newspapers. But it has happened in Britain today—to a man who last picked up his pen in 1796.” (Hint: think New Year’s Eve.)

Apple’s iOS 8 includes QuickType, a predictive typing feature that suggests words you might want to type next. Followed to its extremes, it takes one’s sentences to strange and arguably poetic lands: “I have a great way of saying the government has ordered a pizza./ Yes, you do that for the rest of the day before I go to sleep.”

Ben Lerner and Ariana Reines in conversation: “For me, the cow is a real modernist figure. I feel like after God died, the cow became the onlooker in great works of modernism. It’s the witness in Joyce, it shows up again and again—for me, it’s like the residue of the divine in the twentieth century.”

In the eighties, Michael Chabon had a punk band in Pittsburgh. They were called the Bats. One of his bandmates said, “I just remembered being very impressed with his stage presence, like he’d been waiting all his life to do this.”

September 17, 2014

MacArthur Fellows, Past and Present

Amy Clampitt’s former home in Lenox, MA. Photo via NPR

Congratulations to the MacArthur Foundation’s twenty-one new fellows, including the graphic memoirist Alison Bechdel, whom the Daily was fortunate to interview back in 2012:

Most people are oppressed in some way or other by their family’s expectations, by their parents’ psychological issues, by any number of things. And it holds us back, it limits who we can be in the world. We’re so consumed with our personal problems that we’re not doing more important things. I mean, who am I to talk? All I do is sit in my basement making notes about my therapy sessions. But I want us all to be autonomous and think for ourselves and do the things we’re good at, and I think that’s much more the exception than the rule for people. Not to mention living in a democracy that’s functional. I mean, if we were all really doing those things, what would our world look like?

This latest round of “genius grants”—always with those pesky tone quotes!—inspired NPR to look back at the work of Amy Clampitt, whose poems the Review occasionally published before her death in 1994. Clampitt, a 1992 MacArthur fellow, used her grant money to buy a home in Lenox, Massachusetts, “a small, clapboard house that became the seventy-two-year-old poet's first major purchase.” Soon after, Clampitt was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and her husband Richard Korn

dreamed up a fund to benefit poetry and the literary arts. Since 2003, the house Clampitt bought with her MacArthur money has been used to help rising poets by offering six- to twelve-month tuition-free residencies …

This December, the nineteenth resident of the house Amy Clampitt purchased with her MacArthur purse will settle in, get to work and likely draw on some of the same things that inspired Clampitt. Among them is a small box on the mantel filled with the late poet's beach glass collection.

Clampitt was interviewed for our Art of Poetry series in the Spring 1993 issue, where she elaborated on another collection of sorts:

My own original handwritten drafts are usually on the backs of those silly announcements law firms send out, that so-and-so has just been appointed a partner, which would otherwise go into the wastebasket, and which my best friend Hal, a law professor, saves for me. They’re printed on fine creamy vellum, and they’re very small—four-by-six inches or so, though maddeningly there isn’t even a standard size. I’ve put away stacks of these things for a single poem.

Below is an abbreviated list of Paris Review contributors who have been awarded grants over the twenty-three years of the Fellows program:

A. R. Ammons

Donald Antrim

John Ashbery

Andrea Barrett

Joseph Brodsky

Anne Carson

Guy Davenport

Lydia Davis

Deborah Eisenberg

William Gaddis

Jorie Graham

Aleksandar Hemon

John Hollander

Richard Howard

Edward P. Jones

William Kennedy

Jonathan Lethem

Richard Powers

Kay Ryan

Charles Simic

Mark Strand

Derek Walcott

David Foster Wallace

Robert Penn Warren

John Edgar Wideman

Extreme, Extreme!

The literature of laughing gas.

“This is not the Laughing, but the Hippocrene or Poetic Gas, Sir.” Colored etching by R. Seymour, 1829, via the Wellcome Library.

What’s mistake but a kind of take?

What’s nausea but a kind of -ausea?

Sober, drunk, -unk, astonishment.

Everything can become the subject of criticism—how criticise without something to criticise? Agreement—disagreement!!

Emotion—motion!!!

These words were set to paper in 1882 by William James, one of the most celebrated proponents of the new science of psychology, and a newly minted assistant professor of philosophy at Harvard. James was in many ways the paragon of an eminent Victorian—his writing tends to summon images of the author ensconced beside a roaring fire in some cozy wood-paneled study in Cambridge. And yet here James comes off as utterly, absurdly stoned.

Because he was.

After huffing a large amount of nitrous oxide, James set out to tackle a prominent bugbear of 1880s intellectual life: Hegelian dialectics. He came up with a stream of consciousness that centered on a kind of ecstatic binary thinking:

Don’t you see the difference, don’t you see the identity?

Constantly opposites united!

The same me telling you to write and not to write!

Extreme—extreme, extreme! Within the extensity that “extreme” contains is contained the “extreme” of intensity

Something, and other than that thing!

….

By George, nothing but othing!

That sounds like nonsense, but it’s pure onsense!

Thought much deeper than speech … !

Medical school; divinity school, school! SCHOOL!

Oh my God, oh God; oh God!

James acknowledged to his readers that these ravings were the product of a mental state that, like alcohol intoxication, “seems silly to lookers-on.” But he came away from the experience with a remarkably positive take on nitrous oxide. James had argued that drunkenness produced a kind of “subjective rapture” occasioned by its ability to make “the centre and periphery of things seem to come together.” Nitrous oxide, he believed, produced a similar effect, “only a thousandfold enhanced.” On the gas, his mind was “seized … by logical forceps” and jolted into a new order of consciousness which, he thought, made the logic of Hegelian dialectics perfectly obvious to him.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about James’s experience report is that it didn’t appear in a private diary or letter, but in public, in one of the most eminent psychological journals of his day. What today might be taken for sophomore-dorm drug ramblings was, in the 1880s, novel enough to be cutting-edge science. Nor was James alone in his fascination with recreational drug use. Three years later, a young Sigmund Freud would publish “Über Coca,” usually regarded as the first scientific study of cocaine—but also a paean to the recreational abuse of the drug, which Freud engaged in with considerable gusto.

A young William James looking decidedly anachronistic in Brazil, 1865. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Cocaine, of course, would rise to prominence in the twentieth century. It was immortalized in hit songs; it fueled (fuels?) Hollywood; Woody Allen sneezed in it. There’s no comparable cultural space for nitrous oxide. Today, the drug summons up vague images of wayward fifteen-year-olds huffing cans of Reddi-wip in muddy parking lots.

Things were different once. In a recent article for The Public Domain Review, Mike Jay explores the summer of 1799, when the newly discovered “laughing gas” became a surprise hit among a group of adventurous London aristocrats that included Sir Humphry Davy and Coleridge.

The early reviews were rapturous. “When the bags were exhausted and taken from me,” wrote one early user, “I continued breathing with the same violence, then suddenly starting from the chair, and vociferating with pleasure, I made towards those that were present, as I wished they should participate in my feeling.” Coleridge described “a highly pleasurable sensation of warmth over my whole frame, resembling that which I remember once to have experienced after returning from a walk in the snow into a warm room.”

Sir Humphry Davy was the drug’s most ardent proponent. During full moons in the summer of 1799, Jay writes, Davy took to “inhaling the gas under the stars and scribbling snatches of poetry and philosophical insight.” By winter, Davy had progressed to building “an air-tight breathing-box,” which he entered “with a curved thermometer inserted under the arm, and a stop-watch,” and proceeded to pump full of nitrous oxide. Davy proceeded to get ever-more intoxicated: first he felt a warm sensation in his chest, then points of light in his eyes and “a sense of tangible extension highly pleasureable [sic] in every limb.” At length, “as the pleasurable sensations increased,” Davy “lost all connection with external things” and fell into a fugue state. “I existed in a world of newly connected and newly modified ideas,” he remembered. “I theorized; I imagined I made discoveries.”

Davy’s takeaway from this experience—“Nothing exists but Thoughts!”—bears a family resemblance to James’s Hegelian ranting of eighty years later. In both cases, eminent scientists engaged in an extreme form of nitrous oxide intoxication and came away from it with what they believed to be a new understanding of epistemological fundamentals. And in both cases, neither of their insights made much sense to sober audiences.

Despite this, James’s experiment seems to have had a real effect on his philosophical thought. In December of 1880, James had written to his friend Charles Renouvier that “my principal amusement this winter has been resisting the inroads of Hegelism in our University,” calling it “fundamentally rotten and charlatanish.” After his 1882 nitrous encounter, James had undergone a shift in thinking. The gas’s “first result,” he wrote, “was to make peal through me with unutterable power the conviction that Hegelism was true after all, and that the deepest convictions of my intellect hitherto were wrong.”

Twenty years later, in his most famous work, The Varieties of Religious Experience (1901), James would cite the nitrous experiment as the basis for one of his most celebrated and oft-quoted observations about human consciousness:

I myself made some observations on … nitrous oxide intoxication, and reported them in print. One conclusion was forced upon my mind at that time, and my impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.

Sixty years later, another young professor of psychology at Harvard would argue something similar: his name was Timothy Leary. But there’s something about the reports of James and Davy that make them, for me, at least, far more compelling than the self-indulgence of the 1960s drug writers. They’re not only trippy—they’re exuberant, experimental, playful, funny, honest, and intellectually curious. The literature of laughing gas turns out to be worth a huff or two.

Benjamin Breen is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin and the editor-in-chief of The Appendix, a new journal of narrative and experimental history. His writings have appeared in Aeon, The Atlantic, The Public Domain Review, and The Journal of Early Modern History. He is currently writing a book on the origins of the global drug trade and is on Twitter.

Life Studies

A subway ad for the latest “Body Worlds” exhibition.

With the passage of time come certain revelations. Sometimes these are melancholy; people you love are aging, your window for having a family is shrinking, you will never again know the euphoria of youth. Others are welcome. It is comforting to know there will always be more good books to read than there is time in the average life. And I know I can die happily—and will—without ever going into space, swimming with dolphins, or visiting any one of the endless iterations of that “Body Worlds” exhibition.

When the first such exhibition made its grand tour (in the manner of young gentlemen of a past age), it was a novelty. Vaguely shocking, even—remember the ethics review? Everyone was amazed at the artistry of the preservation. One could lend credence to the creators’ arguments that it taught valuable anatomical lessons and educated the public about biology and physiology and, in so doing, helped encourage healthy lifestyle choices. Imagine how much effort such a show might have saved Michelangelo—to say nothing of grave-robbing Scottish medical students!

As to the bodies themselves, they are all given freely and maybe even joyfully. The web site explains,

The BODY WORLDS exhibitions rely on the generosity of body donors; individuals who requested that, upon their death, their bodies could be used for educational purposes in the exhibition. All the whole-body plastinates and the majority of the specimens are from these body donors; only some organs, fetuses, and specific specimens that show unusual conditions come from old anatomical collections and morphological institutes. As agreed upon by the body donors, their identities and causes of death are not disclosed. The exhibition focuses on the nature of our bodies, not on telling personal information. Currently there are more than 14,000 donors registered in the body donation program of the Institute for Plastination. For more information please visit the body donation section. BODY WORLDS exhibitions are based on an established body donation program through which the body donors specifically request that their bodies could be used in a public exhibition after their deaths.

But wandering past an urbane specimen displayed on a “Body Worlds” poster the other day, I couldn’t help but wonder how much agency the donor had. Say I died with intact musculature and wanted to donate my corpse for educational purposes and be preserved via the magic of Plastination. So far so good. Could I specify that I did not want my body dressed vaguely like a naked Truman Capote on Saint Patrick’s Day, and placed in the map seat (the worst seat of all) on what looks like a 1 Train? After all, as a friend of mine observed, one of the primary benefits of dying is never again having to ride the subway.

It is highly irresponsible of me to critique a show I have never visited; rather like piling on The Death of Klinghoffer without having so much as glanced at the libretto. And certainly, stripping death of its terror can only be a good thing—the American way of death, as we know, is a modern phenomenon. In a sense, “Body Worlds” (and its siblings and offspring) are logical offshoots of time-honored phenomena like the Mütter Museum, or even Victorian postmortem photography. We are never not macabre. And that, too, is comforting.

Austenites Resplendent, and Other News

Photo: Jane Austen Festival

“Madame Bovary, c’est moi” is all well and good as a witty rejoinder—but in all honesty, which of the women in Flaubert’s life was the real Madame Bovary?

At a Jane Austen festival in Bath, 550 people claimed the world record for “the largest gathering of people dressed in Regency costume.”

On “reading insecurity,” the newest existential disease: “the subjective experience of thinking that you’re not getting as much from reading as you used to. It is setting aside an hour for that new book … and spending it instead on Facebook.”

Among Stephen King’s “most hated expressions”: many people, some people say, and YOLO. (I agree with the first two, but I’ll go to the mat for YOLO any day of the week.)

What’s it like to translate a compendium of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s sadistic fantasies? Haunting, but, you know, in a good way: “As translator, I am a filter for material: it travels through me. As such, there’s a residue, but it is difficult to qualify. At best, you might compare the book’s effect on me to its effect on any reader: certain images—many, in fact—remain in you, and surge forth unbidden, superimposing themselves in your mind’s eye on perfectly anodyne and serene scenes of everyday life.”

September 16, 2014

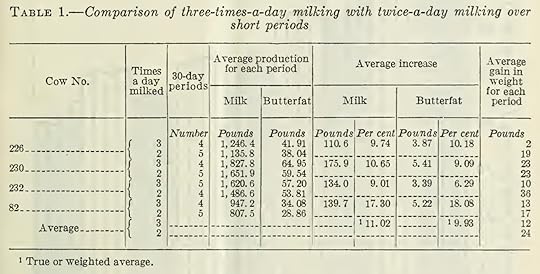

The Production of Dairy Cows as Affected by Frequency and Regularity of Milking and Feeding

It’s late, and you’re still awake. Allow us to help with Sleep Aid , a series devoted to curing insomnia with the dullest, most soporific prose available in the public domain. Tonight’s prescription: “The Production of Dairy Cows as Affected by Frequency and Regularity of Milking and Feeding,” circular 180 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture , published in September 1931.

In the management of the dairy herd, milking requires more time and labor than any other phase of the work. The application of recent findings regarding the secretion of milk and the development of milking machines may be expected to produce important changes in the frequency and also in the manner of milking. At the United States Dairy Experiment Station at Beltsville, Md., the Bureau of Dairy Industry has carried on experiments x on the effects of the frequency of milking, change of milkers, and regularity and irregularity in the hours of milking and feeding on the cows’ production of milk and butterfat. The results of these experiments are reported and discussed in this publication.

FREQUENCY OF MILKING

MILKING THREE TIMES A DAY AS COMPARED WITH TWICE A DAY

It is generally known that cows produce more milk if milked three or four times a day than if milked twice a day. Just how much more milk will be produced, however, is a matter upon which investigators differ. Some of the results obtained in comparing three with two milkings a day are as follows: At the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of Vermont, two cows milked three times a day, in trial periods of 3 to 14 days, gave less milk than when they were milked twice a day. Walker, after carrying on an experiment at Offerton Hall, England, in which he used two groups of five cows each, reported as follows:

So far as milking three times a day is concerned, the results obtained in these experiments show no advantage whatever. On the contrary, the extra driving and other undue interference with the treatment of the cows has produced results of a negative character.

At the Ontario Agricultural College, Canada, two cows milked three times a day for two weeks gave more milk, but only one of these cows gave more butterfat, than when milked twice a day. At the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, cows producing about 400 pounds of butterfat a year when milked twice a day gave only about 22 pounds more when milked three times a day. Fleischmann estimated the increase in yield to be about 6 or 7 percent for milking three times a day as compared with twice. According to Huynen, the milk yield when cows were milked twice a day as compared with three times was about 1 per cent less for cows yielding 10 liters and 10 per cent less for cows yielding 30 liters or more, with an average for the herd of about 6 or 7 per cent less. The milkings were 12 hours apart when made twice a day; and 5K 3 6K, and 12 hours apart when made three times daily.

At the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of New Hampshire, two cows milked three times a day for three days gave slightly more milk and somewhat more butterfat than when milked twice a day. Biford reported that a herd of 50 cows which averaged 45 pounds of milk a day when milked twice daily, gave 4 pounds more per cow when milked three times a day for two weeks. Smeyers found that 34 cows which yielded 8.5 to 17 kilograms (18.7 to 37.5 pounds) of milk daily when milked twice a day, averaged 8 per cent more milk and 13 per cent more butterfat when they were milked three times a day for seven days. At the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of Idaho three cows milked two, three, and four times a day gave relative yields of 60, 75, and 100 pounds of milk. Thirteen cows milked three and four times a day gave one-fourth more milk when milked four times a day than when milked three times. With twice-a-day milking the peak of production was reached in about three weeks; with the other two methods of milking the peak was reached in about six weeks. In the work referred to above, milking three times a day generally resulted in greater milk production per cow than milking twice. However, the increase in the amount of milk that might be expected over long periods was not determined, as only one or two of the trials exceed a few weeks in length. In order that he can decide whether it would pay him to milk his cows more than twice a day, the farmer should know how much extra milk he may expect to get from his herd by milking oftener than twice a day for both long and short periods. It was for the purpose of getting such definite information that the Bureau of Dairy Industry conducted the experimental work reported herein.

SHORT-PERIOD EXPERIMENT

Four Holstein cows (three registered and one grade), soon after freshening, were milked two and three times a day in alternate periods of 40 days. The experiment was continued for 360 days, making nine periods for each cow. In this experiment, three of the cows were started on a period of twice-a-day milking and therefore ended with a period of twice-a-day milking, and one was started and ended with three-times-a-day milking. These four cows were good producers, their average daily yield when milked twice a day varying from 27 pounds for the lowest producing cow to 55 pounds for the best. The average for the four cows was 42 pounds. The cows were kept in box stalls, were fed three times a day, and were given approximately the same quantity of feed regardless of the number of times milked. The results of this experiment are given in Table 1, which shows that milking three times a day resulted in a production of about 11 per cent more milk and 10 per cent more butterfat, on the average. In this table the Jesuits of the first 10 days of each 40-day period were not included, as this time was allowed for the cows to become accustomed to the change in order of milking. The experimental results therefore cover only the last 30 days of each 40-day period.

The chart in Figure 1 shows the production of cow No. 230 in alternate 40-day periods. In this chart, each 40-day period is sub- divided into 10-day intervals, including the first 10 days of each period. In the first period the milking was twice a day. The production of this cow is characteristic of the production for the group. The chart shows that every change from milking twice a day to milking three times a day resulted in an increase in production, whereas every change from three times to twice a day resulted in a decrease. Furthermore these changes were immediate. The smaller gains in body weight made by the cows when milked three times a day, as shown in Table 1, were to be expected. As has already been stated, the cows received the same amount of feed during the entire experiment. Since milking three times a day resulted in a greater production of milk, less nutriment was available for making body fat.

Still awake? Read on here.

Cardboard, Glue, and Storytelling

Katherine Treppendahl’s design for Ulysses.

Last year, Sadie Stein wrote here about Matteo Pericoli’s Laboratory of Literary Architecture, a “cross-disciplinary exploration of literature as architecture” in which students create physical models of literary texts. Pericoli has taught the course at the Scuola Holden in Italy, at Columbia University, and elsewhere—now he’s broadening the horizons, and the Laboratory has a robust new Web site to prove it. There’s also a new video—replete with a kind of slinky Sade-ish groove, because why not?—that walks you through the course’s fundamental questions.

But perhaps the easiest way to grasp what Pericoli’s up to here is to look at an example—the LabLitArch site features a number of them. Here, for instance, is Katherine Treppendahl, an intern architect, on her workshop design for Ulysses, seen above:

The exterior space frame represents the overarching role of Joyce, the arranger, as well the modules of time within the text—each partition represents a different time of day. The two primary characters, Bloom and Stephen (Joyce’s Ulysses and Telemachus) are translated into different volumetric typologies. These volumes are stacked and arranged in terms of their presence, importance, and relationship within the story. The reader is represented as a pale tube snaking through these volumes. In the novel, there is a point at which the text shifts from a more conventional narrative style to a more abstract and self-conscious style. Within the model, as the reader moves into this territory, the volumes begin to break open and fracture. They are no longer whole vessels, and the “reader” is visible, moving uncertainly through this landscape.

There’s also a very fitting makeshift mission statement drawn from Alice Munro’s Selected Stories:

A story is not like a road to follow … it’s more like a house. You go inside and stay there for a while, wandering back and forth and settling where you like and discovering how the room and corridors relate to each other, how the world outside is altered by being viewed from these windows. And you, the visitor, the reader, are altered as well by being in this enclosed space, whether it is ample and easy or full of crooked turns, or sparsely or opulently furnished. You can go back again and again, and the house, the story, always contains more than you saw the last time. It also has a sturdy sense of itself of being built out of its own necessity, not just to shelter or beguile you.

Check out more of the student projects here.

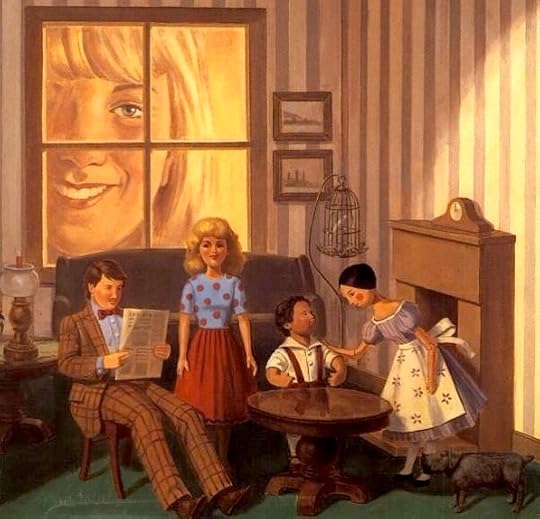

As Dolls to Wanton Kids

Detail from the cover of The Doll’s House.

It is an anxious, sometimes a dangerous thing to be a doll. Dolls cannot choose; they can only be chosen; they cannot ‘do’; they can only be done by. Children who do not understand this often do wrong things, and then the dolls are hurt and abused and lost; and when this happens dolls cannot speak, nor do anything except be hurt and abused and lost. ―Rumer Godden, The Doll’s House

Rumer Godden was preoccupied with dolls. In her many stories about dolls—including Miss Happiness and Miss Flower, Little Plum, Home Is the Sailor, and, of course, The Doll’s House—we are presented with a cast of characters who are at the mercy of children. Some children are rough and wild; others are conscientious and intuitive. They are little gods, and the dolls are their playthings, and when they feel powerless in their own lives, it is the dolls who bear the brunt of this powerlessness. Godden wasn’t the only author to recognize this essential dynamic—The Velveteen Rabbit, Hitty, and later Toy Story truck in the same themes—but no one makes that reality as scary and lonely as she does.

Of all the books, The Doll’s House is perhaps the most sinister. We have Tottie, the stable peg doll; the doll father, who seems to suffer the aftereffects of a rough owner; the mother, who is made of celluloid and so somewhat dotty and scattered. And there is the evil, beautiful Marchpane—more financially valuable in the real world than the others. The dolls are survivors who have found each other—their relationships are resolutely asexual, by the way—but their peace can be shattered by a gust of wind, a candle flame, a child’s whim. It is scary stuff, and compelling, too. There is tragedy here, but even before the tragedy, there is menace.

Of course this appeals to a child. Children are both dolls and masters; they know their powerlessness and need to understand their power. While the subject matter sounds sweet, it becomes a stage for something far darker.

They made a film of The Doll’s House, and while I don’t think it captures the charm of the book completely—Tasha Tudor illustrated one version—it is strange and forceful in its own right.

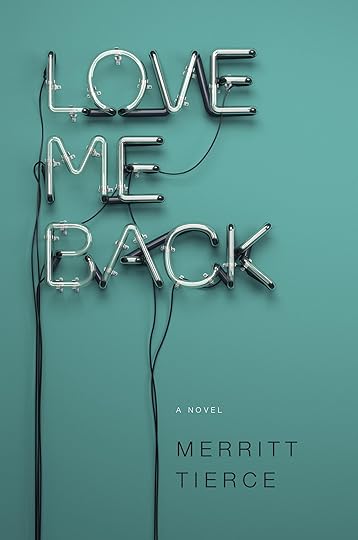

Freedom to Fuck Up: An Interview with Merritt Tierce

Photo: Michael Lionstar

In Merritt Tierce’s debut novel, Love Me Back, life does not go as planned. A Texas high school student named Marie becomes pregnant on a missionary trip when she’s only sixteen. The event completely changes Marie’s life. Raising a child means not going to college, marrying a boy she’s only just met, and cutting short her own adolescence. Tierce writes poignantly of the pain and loneliness in Marie’s new life—as a waitress at a restaurant where the only thing that feels permanent is what her life has become. She tests her boundaries and her limits, numbing herself from reality with sex, drugs, and pain. And while it’s a hard life on the page, Love Me Back is also filled with the kindness and humor that people offer one another when they know there’s no one else. Tierce is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she was a Meta Rosenberg Fellow; she is also a recipient of the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award.

You write of Marie’s pregnancy, “I don’t hear my whole life being written for me inside my body, cell by cell.” Marie had been accepted into Yale, but the baby completely upends her plans and distances her from her family. One of the earliest scenes in the novel is Marie’s interview at the Olive Garden—it signals the beginning of her life as a young mother in the service industry. What drew you to start at this point?

I wrote the book backward, chronologically—so I actually started at the latest point in Marie’s life. I knew what she felt and thought in the stories in the second half of the book more clearly than I knew younger Marie. I had to write back through her states of mind, back toward childhood. She was still a child when she became pregnant and I had to approach that fog carefully. Marie is unknown to herself at the beginning of the book, and I couldn’t start there. It felt like the gameplay in something like World of Warcraft, where you can only see as much of the map as you’ve explored. The rest is dark. While Marie was living it, she had to emerge from the dark and settle her territory—but while I was writing it I could only write out to the edge of black. I respected that. I let her be what she was—aware, but ignorant. New. And I can’t make any categorical statements about sixteen-year-old mothers, but my hope for my own daughter is that she lets herself find and grow and use her power for herself before she lets anyone else lay claim to it.

I’ve thought a lot about how both MTV’s Teen Mom and 16 and Pregnant series revealed the realities, highly edited, of teen pregnancy to a wider audience. There’s also a lot of new work, from women, that deals directly, and with a frank sense of humor, about accidental pregnancy and abortion—Jenny Slate’s Obvious Child, Emily Gould’s Friendship, even Juno. What do you think about the current conversation in our culture about pregnancy and abortion?

I think the culture and the conversation still have a long way to go, but Obvious Child is a great start. Efforts like Sea Change, Not Alone, All* Above All, and 1 in 3 give me a lot of hope because people are realizing it’s a long game. Abortion is the best-kept secret, in that it’s an experience so many women have—but they have it alone or with the one person who goes through it with them, whoever that may be. Most people don’t know anything about abortion until they need an abortion or someone close to them needs an abortion—and then they learn everything about abortion in a compressed timeline, under the stress of both their own circumstances and the stigma forced on them. They have the abortion and then they go on with their lives. But we have to stop pretending that abortion is an experience one has to earn or justify, and that means we have to talk about it. About how common it is, and how there might not be a lot to say about most abortions—someone got pregnant and they didn’t mean to, someone just doesn’t want a kid right now, someone isn’t sure about a lot of things and has trouble making decisions. It’s hard to report that story because it’s not “compelling,” but it’s the most common abortion story there is—a woman knows she doesn’t want to have a child so she has an abortion in the first trimester and the procedure itself takes less than five minutes. Abortion has been around as long as pregnancy, and our responsibility is to let it be complex and to make it safe and accessible. And most of all to not question people when they choose abortion—to let them be the experts on their own lives.

Obvious Child is so frank and so hilarious and I hope everyone sees it. There was hardly a line I didn’t laugh at, and my husband and I took our daughters, who are twelve and thirteen, because we thought it was practically a how-to for getting through that inevitable extended moment in your life when you’re good at some things and terrible at others and you don’t know if you’re going to make it. And it’s okay if all kinds of things go into that soup, including abortion.

Marie copes with her sense of alienation and depression by abusing drugs and alcohol as well as practicing other forms of self-destructive behavior, like casual sex and cutting herself. It sounds dark in summary, but I found those passages to be some of the most beautiful in the book. So much of what she is doing is avoiding any real sense of intimacy and disguising her pain. What was it like to write those scenes?

Marie copes with her sense of alienation and depression by abusing drugs and alcohol as well as practicing other forms of self-destructive behavior, like casual sex and cutting herself. It sounds dark in summary, but I found those passages to be some of the most beautiful in the book. So much of what she is doing is avoiding any real sense of intimacy and disguising her pain. What was it like to write those scenes?

It was like the kind of conversation you can only have with someone on a long car ride or when you’re trapped somewhere. I was in the enclosed space of Marie and I felt what she felt, both the deep sadness and the dissociation from it. I wanted to write that state of inwardness that is simultaneously so focused on the spark of the pain and on the avoidance of it. For the most part I ignored what she felt and just reported what she did, what she thought, what she saw, and trusted that the feelings would come through because they were there.

I’ve always considered sex scenes, by the way, to be incredibly challenging for most fiction writers. They can be too graphic, too cheesy, completely gratuitous, or total fantasy! But I loved the sex scenes in your novel. Did you look to other writing? Did you come across any, uh, bedroom dos and don’ts when writing?

I didn’t look to other writing. I just wanted it to feel real. And I think that Marie is teaching herself what she doesn’t want. Outlining it, repeating it, making sure she knows what it is and how bad it feels. That’s a painful process, but I don’t think women have enough freedom to fuck up in general, and even less when it comes to sex. The sex in Love Me Back is also not so much sex as it is just another way Marie hurts herself, so maybe I had more set boundaries than a writer typically does with a sex scene.

You live in Texas, where you work as the executive director of the Equal Access Fund, which provides financial support for those who can’t afford abortions. In what ways does this job inform you as a writer?

I’m constantly working on behalf of people who have nothing. They are homeless, they are living in violent situations, they have children they can’t support and children who have been taken from them. They have debilitating health issues and no money. They are twelve years old and were raped. My job is listening to their stories and then telling those stories to other people who have more than nothing, asking them to care. Chekhov said, “People must not be humiliated, that is the main thing.” I think about that all the time. I think about how shame is the most powerful force and you could write a story about anything horrific or depraved that someone did because of shame and it would feel true. Yes, you would think, someone could possibly do that most craven thing, because of shame. My urge to write and the focus of my job are both motivated by a need to reject unwarranted shame absolutely and explicitly. People have a right to healthcare that includes abortion, and they shouldn’t have to beg for it.

Some of my favorite characters were drawn from the scenes of Marie’s later job, at a five-star steakhouse in Dallas, where excess is the norm. Customers spend thousands and thousands of dollars on a dinner. Danny, the charismatic and hedonistic owner, is coked out of his mind, flirting and fucking women in the restaurant. I was wondering how you considered humor and caricature when writing these scenes—how humor can underpin Marie’s sadness in a really effective way.

Stories don’t feel real if people never laugh. Even in the most unbearable circumstances, people still laugh—and as one draws closer to death through illness, corruption, age, or violence, it can sometimes be easier to see the absurdity of life and laugh at it. You’re on the edge of the coin. Marie sees the excess up close but she pulls back to think about it and lets the humor in because it helps and it’s worth something.

Thessaly La Force is a writer based in New York.

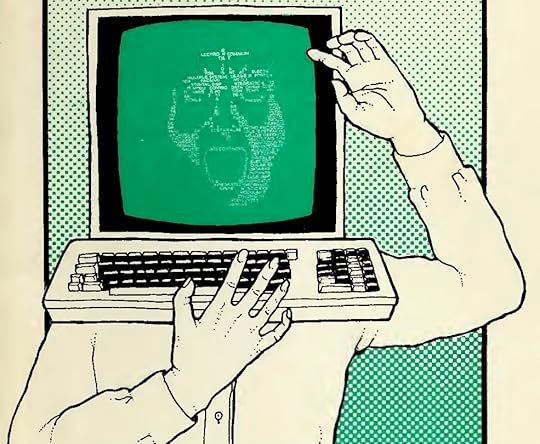

“Are You Being Processed?” and Other News

Detail from the cover of the first issue of Processed World, 1981.

The National Book Awards have published this year’s poetry longlist: Louise Glück, Edward Hirsch, and Fanny Howe are among the ten nominees.

Technology was supposed to increase our leisure time and enliven our workplaces—that hasn’t really panned out. But in the early eighties, amid all the Pollyannaism of the Bay Area, a magazine called Processed World seemed to foresee all the resentments of the contemporary office drone. “In the writing … one can also find the beginnings of today’s revolt against Silicon Valley and its pernicious mix of libertarian economics, techno-utopianism, and the deracinated remains of the sixties counterculture.”

“Fingerprint words”: the words and phrases we overuse to the point that they become our personal trademarks. (Mine are probably foresee, edify, and floccinaucinihilipilification.) The strangest thing about these words is that they’re contagious: “We’re all simultaneously donating to and stealing from those around us. But how do we pick up these linguistic signature words, and what is going on when we notice other people using those words and we feel, well, a certain way about it?”

Writers seeking peace, quiet, and old-fashioned American bonhomie: Washington, D.C.’s Politics & Prose is renting a cottage in Ashland, Virginia—a town where “people wave at you from their front porch”—for weeklong retreats.

On the performative paintings of Avery Singer: “The gentle sarcasm embedded in her work is usually aimed at art-world stereotypes. Her first solo exhibition at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler in Berlin last year, for example, was a satiric take on the art industry and its conventions. Works with titles such as The Studio Visit (2012), Jewish Artist and Patron (2012) and The Great Muses (2013) play on myths around the romantic figure of the artist. The show was accompanied by a short text by Singer, a fake press release for an exhibition that will never happen.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers