The Paris Review's Blog, page 661

September 22, 2014

The Death of the Pay Phone, and Other News

A man in a Miami retirement community uses a pay phone, 1973. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

It’s Banned Books Week. Read something that some prudish bureaucrat condemned as mind-polluting trash. The options are nearly endless …

Woolf v. Wharton: “Critics exalted Dalloway as an important advance in literature. In the Saturday Review, the critic Gerald Bullett unfavorably compared Wharton’s latest, A Mother’s Recompense, with Mrs. Dalloway, calling Woolf ‘a brilliant experimentalist,’ while Wharton was ‘content to practice the craft of fiction without attempting to enlarge its technical scope.’ ” Wharton was stung by the slight, and disapproved of modernist experimentalism—but it may have goaded her into attempting a “stunning narrative maneuver” in The Age of Innocence.

Among Nabokov’s “menagerie” of pet names for Véra: Gooseykins, Pussykins, Monkeykins.

Graham Greene’s 1952 open letter to Charlie Chaplin, defending him against trumped-up charges from the House Committee on Un-American Activities: “I suggested that Charlie should make one more appearance on the screen … He is summoned from obscurity to answer for his past before the Un-American Activities Committee at Washington—for that dubious occasion in a boxing ring, on the ice-skating rink, for mistaking that Senator’s bald head for a rice pudding, for all the hidden significance of the dance with the bread rolls … at the close of the hearing Charlie could surely admit to being in truth un-American and produce the passport of another country, a country which, lying rather closer to danger, is free from the ugly manifestations of fear.”

Doomsday for NYC pay phones: “Next month in New York City, a contract will expire that requires the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT) to maintain the city’s 8,000 remaining pay phones.”

September 19, 2014

Staff Picks: Catharsis, Consumed, Containers

Photoville, in Brooklyn Bridge Park. Image via Photoville’s Instagram

“‘The first thirty days after that performance ... it hurt. I just wasn’t right. Whatever that was … catharsis … People don’t understand.’” In the new issue of Harper’s, Wyatt Mason has a moving, in-depth profile of Bryan Doerries, a director and translator who stages classical tragedies for veterans suffering from PTSD. —Lorin Stein

There’s no better way to savor the last of these summer evenings than to head to Photoville, a pop-up photography exhibition in Brooklyn Bridge Park. The exhibition comprises sixty-some shipping containers—surprisingly well suited for the purpose—and, over the course of its eleven-day run, will showcase the work of more than four hundred artists. Highlights include Josh Haner’s Pulitzer Prize–winning series on Jeff Bauman and a curated selection of James Nachtwey’s work from his thirty-year (and counting) tenure at Time. The Photoville runs through September 28. —Stephen A. Hiltner

As I read David Cronenberg’s debut novel, Consumed, I feared I was elevating its somewhat typical techno-thriller plot simply because of the filmmaker’s name. It’s too difficult to sum up here, but the story involves yellow journalism, Marxism, black-market organ trafficking, North Korea, 3-D printing, and sex—the latter “in an incredible number of varieties,” as the jacket states. But I needn’t have worried. Hints of what makes Cronenberg’s filmmaking so unsettling and enthralling began to seep in: the detailed horror of violence and its repercussions, unexpected humor (the Marxist philosophers are named Celestine and Aristide Arosteguy), and the plot’s transition from the tech world to the inner turmoil of our finite existences. As Cronenberg once said, “Consciousness is the original sin: consciousness of the inevitability of our death.” —Justin Alvarez

In this weekend’s Times Magazine, along with John Jeremiah Sullivan’s excellent profile of Donald Antrim, is Matt Bai’s piece about Gary Hart, a name that will fire cobwebbed synapses if you followed presidential politics in ’87. (I didn’t. I was a one-year-old.) Hart was the Democratic front-runner that year until a reporter from the Miami Herald got a tip that he’d been sleeping around. As Bai writes, the Herald’s sanctimonious coverage of these events—or nonevents—has had ramifications not just in the media but in the very essence of our political character. For fear of being crucified as Hart was, politicians no longer do, say, or believe in anything interesting; they’ve purged themselves of personality, conviction, and contradiction. Buried in Bai’s critique is a canny, surprisingly ardent defense of humanism: “As an industry, [the media] aspired chiefly to show politicians for the impossibly flawed human beings they are: a single-minded pursuit that reduced complex careers to isolated transgressions. As the former senator Bob Kerrey, who has acknowledged participating in an atrocity as a soldier in Vietnam, told me once, ‘We’re not the worst thing we’ve ever done in our lives, and there’s a tendency to think that we are.’ That quote, I thought, should have been posted on the wall of every newsroom in the country, just to remind us that it was true.” —Dan Piepenbring

With all the sunshine we’ve been enjoying in New York this September, it seems hard to believe that the autumnal equinox is almost here. As I’m returning to England tomorrow, where it will probably be winter and almost definitely raining, the realization that summer is over is now sinking in. And my mental countdown was only intensified by revisiting Elizabeth Bowen’s The Last September, a novel that centers on Ireland’s Anglo-Irish community during the early twenties, when the War of Independence finally broke through their isolated bubble of tennis and tea parties. Okay, so our situations are not quite analogous. But the magnetism of Bowen’s writing pulls you into a smoldering autumnal landscape that only heats up as the novel progresses, and the Irish rebels close in on “the big house” and its inhabitants. Growing up as an Anglo-Irish child herself, Bowen once remarked that she grew “accustomed to … being enclosed in a ring of almost complete silence.” It’s the breaking of this silence that The Last September captures so well, with those seasonal reds and oranges transforming into warning signs for an inevitable fall. —Helena Sutcliffe

Disco Purgatorio

Divina. Photo: Antonio La Grotta

The Italian photographer Antonio La Grotta has done what some intrepid ruin pornographer ought to have done years ago: he’s taken pictures of Italy’s abandoned discotheques.

Topkapi.

In the boom times of the eighties, these discos sprang up across the Italian countryside, shrines to saturnalia and synthesizers. Now there are purgatories where once there were infernos. La Grotta describes these edifices as “fake marble temples adorned with Greek statues made of gypsum, futuristic spaces of gigantic size, large enough to contain the dreams of success, money, fun … ” Now the discos are just “cement whales laid on large empty squares, places inhabited by echo and melancholy.”You can see more of La Grotta’s photos on his website and on Slate’s Behold blog, but you should set the mood first. Here’s Kano’s “I’m Ready,” seven minutes of blissed-out Italo-Disco that will help you mourn a bygone era and celebrate Friday night.

Expo.

The Favorite Game

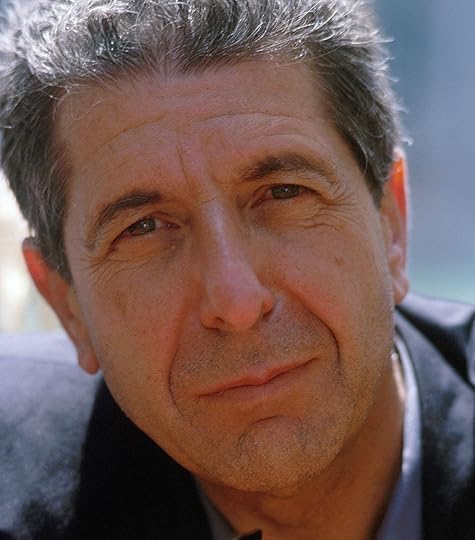

Leonard Cohen in love.

Cohen in 1988.

“Desperation is the mother of poetry.”

—Leonard Cohen

Like most people, I remember the first time I had sex pretty well. I can recall the surprisingly adept flirting I carried off beforehand, and the moment of pleasant shock when she kissed me. I remember how we stayed in bed until three the next day and how when we finally got up, faint from hunger, we went to eat at a greasy spoon that had a little jukebox by each table. I have no idea what I ordered, but I do remember that she got a grilled cheese sandwich. In the next year and a half that we were together, I don’t know if she ever ate another one.

We all have memories like that, jumping out of oblivion like buoys in the water. The facts might be fuzzy, but the moments are clear. Leonard Cohen describes such a memory in his first novel, The Favorite Game, published in 1963, when he was twenty-nine:

What did she look like that important second?

She stands in my mind alone, unconnected to the petty narrative. The color of the skin was startling, like the white of a young branch when the green is thumb-nailed away. Nipples the color of bare lips. Wet hair a battalion of glistening spears laid on her shoulders.

She was made of flesh and eyelashes.

Cohen, who turns eighty on Sunday, is exceptionally good at drawing out those moments of sexual crystallization. It’s a skill that, along with his gravelly voice and poems about women’s bodies, has given him a reputation for being a “ladies’ man.” Judging by the adoring crowds at his shows, it’s a reputation he deserves.

Yet it isn’t success with women that accounts for Cohen’s particular vision, even if his fame as a lover may have, over time, borne the fruits of self-fulfilling prophecy. Rather, his work is shot through with fears of physical deficiency and sexual deprivation, loneliness and insecurity. “He could not help thinking that … he wasn’t tall enough or straight, that people didn’t turn to look at him in street-cars, that he didn’t command the glory of the flesh,” he writes of his autobiographical protagonist in The Favorite Game. Decades later, in his 2006 poetry collection Book of Longing, Cohen confessed: “My reputation as a ladies’ man was a joke / that caused me to laugh bitterly / through the ten thousand nights / I spent alone.”

This experience of rejection explains Cohen’s freeze-frame insight into intimacy. Scarcity, after all, translates into appreciation and appreciation into value. It transforms sex into something more than a bodily function. Along with his focus on physical passion, Cohen is known for his spiritual and religious themes, and for yoking them with the ecstasies of the flesh. Sex for him is not just a pleasant pastime but also a spiritual adventure, the key to life-defining emotions.

Wordsworth, in his poem “Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,” famously expressed the loss of early wonder and the decline into adult insensitivity:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparell’ed in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore; —

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day,

The things which I have seen I can see no more.

Wordsworth was too genteel to factor sex into the equation, but it surely belongs with meadow, grove, and stream. From the mysteries of childhood to the torrent of adolescent desire to the thrill of long-anticipated discovery, there is a power in sexual experience that dissipates with age. It’s easy to remember a first time, or a first encounter with a new person, but what about the repetitions that follow? Even sex becomes dull and forgettable.

For Cohen, a near superhuman appreciation preserves the intensity of original experience. Among his works, The Favorite Game is the most remarkable in this respect. The novel is a bildungsroman of sexual and romantic experience, chronicling the coming of age of Cohen’s stand-in protagonist, Lawrence Breavman. The book ranges from childhood sex games in the garage to Breavman’s effort to hypnotize and undress the family maid—an event that, according to several Cohen biographers, has its basis in the author’s real-life interest in hypnosis. Together with his friend Krantz, Breavman tries to pick up French girls at the dance halls of Montreal and Jewish ones at communist meetings. He is mostly unsuccessful, although he occasionally comes close to his purpose. “Then he was in a room undressing her,” the narrator relates of one attempt:

He couldn’t believe his hands. The kind of surprise when the silver paper comes off the triangle of Gruyère in one piece.

Then she said no and bundled her clothes against her breasts.

He felt like an archaeologist watching the sand blow back.

When Breavman’s efforts finally meet with success, he is beside himself with rapture. “He exulted as he marched home, newest member of the adult community. Why weren’t all the sleepers hanging out of their windows cheering?” It is not just getting laid that he celebrates. Like Konstantin Levin in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, who takes a similarly exalted tour of Moscow after successfully proposing to Kitty Scherbatsky, it is the glory of life that moves him.

But Cohen’s focus on the emotional and spiritual impact of sex has led him in some unfortunate directions. In another artist, feelings of inadequacy might lead to hostility toward women, or outright hatred. “Women seem wicked when you’re unwanted,” Jim Morrison put it simply in “People Are Strange.” In Cohen’s case, the same experiences have resulted in an opposite response—not a hatred of women, but an idealization of them. Better, to be sure, than the more common and vicious misogyny, but troubling in its own way.

Take Cohen’s female characters. They are elegant and mysterious, often wealthy and occasionally prone to suicide. In The Favorite Game, Breavman’s girlfriend belongs to the East Coast WASP elite; in “Sing Another Song Boys,” from his 1971 album, Songs of Love and Hate, she is the “moneylender’s little daughter … eaten with desire.” Cohen’s women are sometimes submissive, sometimes imperious, vulnerable or powerful, dependent on a man or possessing the power to crush him. On other occasions they’re the familiar agents of bourgeois entrapment, domestic numbness and loss of freedom and creativity. But in all of these cases, Cohen’s women run to an ideal of romantic bliss or torture, ecstasy or pain. They are mirrors for Cohen’s own feelings, rather than depictions of human beings.

Cohen also seems convinced that sex is a gift, the result of an unequal relationship. “Because of a few songs wherein I spoke of their mystery / Women have been exceptionally kind to my old age,” he sang on his 2004 album, Dear Heather. However wonderful gratitude might usually be, to offer thanks for sex is to treat it as a service rendered, and to be oblivious of the other person’s pleasure. Perhaps those women also thought of Cohen as exceptionally kind? What of their experiences?

Still, there’s a great deal of truth in Cohen’s depictions of romance. In his early prose he captured the unique claustrophobia of a first relationship—the reluctance to leave even though “commitment was oppressive” because “the thought of flesh-loneliness was worse.” He’s expressed the sadness of separation (“Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye”), the pain of post-breakup memories (“Humbled in Love”), and the torture of failed but impossible-to-end relationships, which he evoked in “The Traitor,” a song I listened to repeatedly before ending things with the same girlfriend I had lost my virginity with a year and a half earlier.

Cohen’s rawness, and the honesty with which he displays his own vulnerabilities, sometimes leads him to extreme positions, granting sex a primacy that it doesn’t deserve. In his view “there is a war between the man and the woman” as well as “a war between those who say there is a war and those who say that there isn’t” (“There Is a War”). He has written, “a friendship between a man and a woman which is not based on sex is either hypocrisy or masochism.” And he has concluded, “when I see a woman’s face transformed by the orgasm we have reached together, then I know we’ve met. Anything else is fiction.”

For me, that’s the voice of a less mature self, for whom deprivation is not just the mother of poetry but of exaggeration. (Cohen sometimes presents himself not just as an initiate but as a master, like a creepy New-Age cult leader telling middle-age women that opening the body is the key to opening the soul.) Then again, who hasn’t cursed the entirety of the other sex after a bad breakup? What else is sexual jealously than the consciousness of someone you love sharing the intimacy of an “orgasm … reached together” with another person? And who hasn’t left someone’s house after a particularly wonderful night, exhausted but ecstatic, grinning stupidly into strangers’ faces?

Usually those emotions, even when we can admit them to ourselves or share them with our closest friends, have to be covered up in polite society. We can’t walk around constantly in the throes of our own private maelstroms. More important, maturity—and good sense—demands that we view each other as human beings who suffer from basically the same problems, not as enemies in a never-ending war of the sexes. We are the perpetrators of pain as well as its victims, we reject and are rejected, desire and are desired. But that knowledge doesn’t lessen the joy and suffering of our innermost selves. It doesn’t diminish the feelings of delight and anger that seem as though they had never been felt before. Only time diminishes them, along with experience, repetition and age.

Except, it seems, for Leonard Cohen. In his work, the bite of those feelings is still sharp. In his albums and novels, memories of love and heartbreak stay on the surface, bobbing up and down. In his poems and songs there is always, as Wordsworth put it, “The glory and the freshness of a dream.” Reading and listening to Leonard Cohen it is always, and forever, the first time.

Ezra Glinter is the deputy arts editor of the Forward. Follow him on Twitter.

No Hours But (Sort of) Sunny Ones

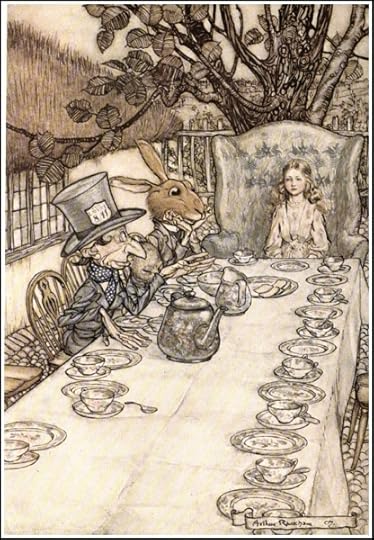

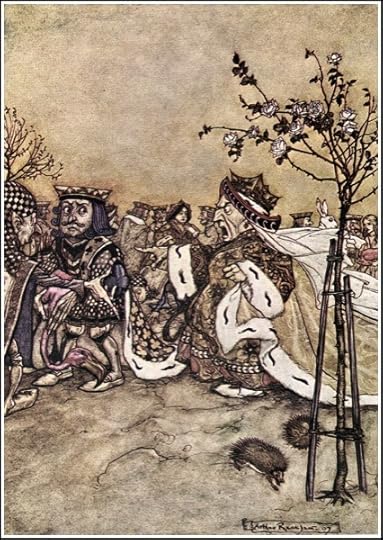

From Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland: a mad tea party.

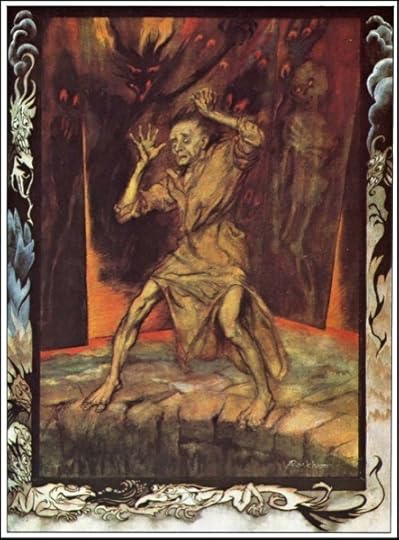

From Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum”

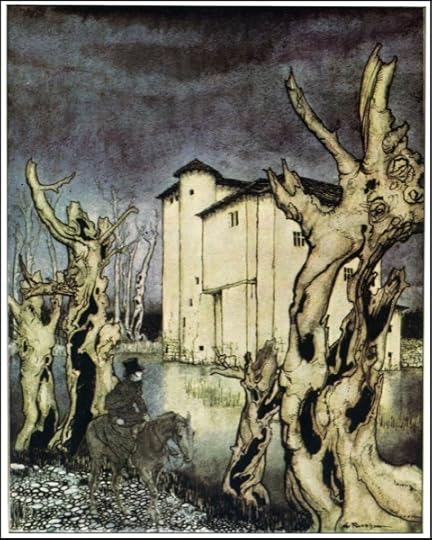

From Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher”

From Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland: “Off with her head!”

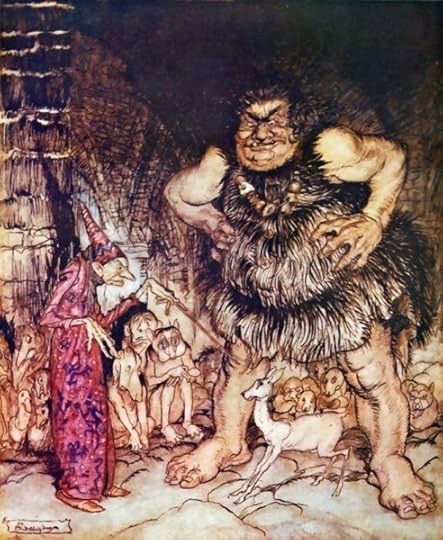

From Galligantus

From Peter Pan: away he flew.

From Jack and the Beanstalk Giant

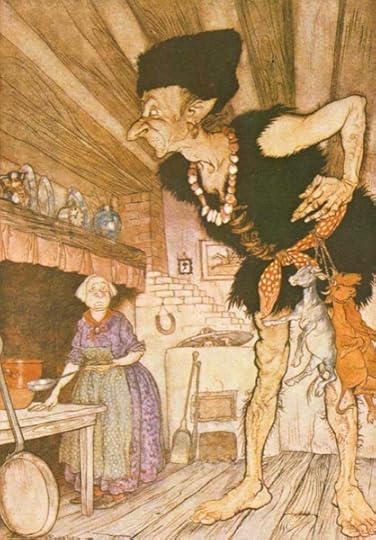

From Wagner’s The Rhinegold and the Valkyries

From Wagner’s Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods

From The Three Bears

You could spend hours marveling at Arthur Rackham’s work. The legendary illustrator, born on September 19, 1867, was incredibly prolific, and his interpretations of Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Rip Van Winkle (to name but a few) have helped create our collective idea of those stories.

Rackham is perhaps the most famous of the group of artists who defined the Golden Age of Illustration, the early twentieth-century period in which technical innovations allowed for better printing and people still had the money to spend on fancy editions. Although Rackham had to spend the early years of his career doing what he called “much distasteful hack work,” he was famous—and even collected—in his own time. He married the artist Edith Starkie in 1900, and she apparently helped him develop his signature watercolor technique. From the publication of his Rip Van Winkle in 1905, his talents were always in high demand.

He had the advantage of a canny publisher, too, in William Heinemann. Before the release of each book, Rackham would exhibit the original illustrations at London’s Leicester Galleries, and sell many of the paintings. Meanwhile, Heinnemann had the notion to corner multiple markets by releasing both clothbound trade books and small numbers of signed, expensively bound, gilt-edged collectors’ editions. When the British economy flagged, Rackham turned his attention to Americans, producing illustrations for Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and later Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Pragmatic he may have been, but Rackham’s detailed work is pure fantasy, alternately beautiful, romantic, haunting, and sinister. Nothing he did was ever truly ugly, although he could certainly communicate the grotesque. And his illustrations are never cute, although his animals—as in The Wind in the Willows—have a naturalist’s vividness, and he could do whimsy (think Alice in Wonderland, or his many goblins) with the best of them. Several generations of children grew up with this nuanced beauty; it’s probably wielded even more of an aesthetic influence than we attribute to it.

Rackham once said, “Like the sundial, my paint box counts no hours but sunny ones.” This is peculiar when one considers the moodiness of much of his palate, and the unflinching darkness of many of his illustrations. I think, rather, of a quote from his edition of Brothers Grimm: “Evil is also not anything small or close to home, and not the worst; otherwise one could grow accustomed to it.” He made that evil beautiful, too, and it was this as much as anything that enchanted.

Boswell’s Prurient Pastime, and Other News

Why is our vice president quoting Thomas Pynchon? In a speech in Des Moines, Joe Biden expounded on this bit of vintage paranoia, from Gravity’s Rainbow: “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.”

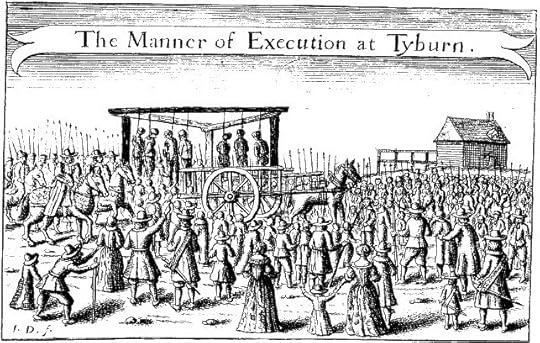

James Boswell had more hobbies than just following around Samuel Johnson; he was also “an inveterate execution goer in an age when such activity was considered prurient for a gentleman … Boswell diligently noted the names and crimes of the condemned: robbery, theft, escaping a prison hulk, forgery and murder. He describes a brother and sister convicted of burglary who met their deaths holding hands, only to be separated when they were cut down from the gallows.” He attended at least twenty-one executions, though they gave him nightmares and depressed him. The best hobbies (e.g., writing) often do.

At a recent school-board meeting in Murphy, Oregon: fuddy-duddies. “Some parents complained Tuesday night that students should not be allowed to read the book Persepolis without parental approval. The novel by Marjane Satrapi contains coarse language and scenes of torture, and it’s in high school libraries within the Three Rivers School District in southwest Oregon.” (“I’m boiling mad,” one parent said.)

The world’s oldest joke book, the Philogelos, dates to maybe the fourth century AD—but are its jokes funny today? The Internet has delivered its unassailable verdict: “kind of, sometimes.”

I’ve mentioned the Write a House project in this space before: it offers authors lifelong residencies in Detroit by renovating vacant homes and then simply giving them to writers. Now the first winner has been announced: the poet Casey Rocheteau, from Brooklyn.

September 18, 2014

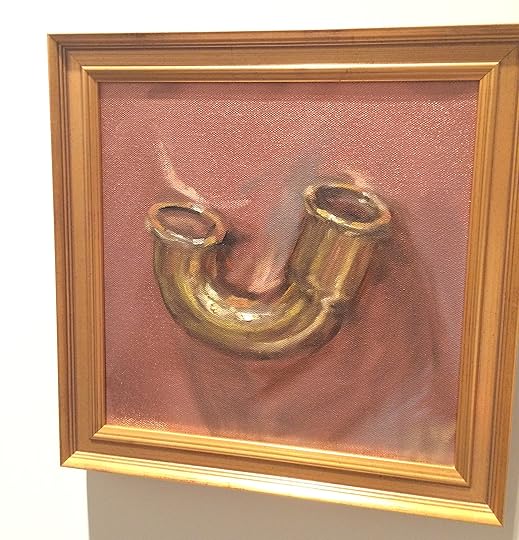

Plumbing the Depths

It was 1917 when Marcel Duchamp debuted Fountain, that perennially scandalous urinal, that Dadaist taunt, that porcelain keystone. Since then, befuddled museumgoers worldwide have asked, “How is that art?”; about half a dozen performance artists have made a show of peeing on, in, or around one of the many replicas of Fountain; and, at the Pompidou Center, one guy threw a hammer at it. But now, in 2014, the artist Alexander Melamid has outdone them all: he’s reconnected the urinal to plumbing. It flushes anew. And through its pipes, he hopes, will flow more than a century’s worth of the art world’s built-up shit.

Melamid’s new exhibition, “The Art of Plumbing,” opened last night at Vohn Gallery. It comprises paintings of assorted plumbing components—sometimes superimposed on canonical works by, say, Picasso or Rothko—with names like Form-N-Fit 1-1/2 Flanged Tailpiece, Large Drain Cleansing Bladder, and The No Clog Drain, Permaflow. At its center, atop a kind of plinth, is a fully functional urinal, its working parts very much visible.

“Modernism in art began in earnest with that urinal, severed from the sewage system. It was a truly revolutionary act,” an accompanying statement read. And yet, as the twentieth century wore on, artists descended into meaningless self-referentiality and the pursuit of wealth, thus necessitating another revolution:

Having acquired the skills to wield both pipe and wrench, the artist Alex Melamid will successfully perform an aesthetic coupling that will flush the human as well as the elephant waste from our great museums. Once sent down the drain and into the sewage system, this effluvial excess will affront the senses of public no longer.

If this “functional and highly effective plumbing environment” seems no more than an elaborate, obvious prank, rest assured that Melamid would agree. For years now, the sixty-nine-year-old, Russian-born artist has taken a boyish glee in playing the part of the gadfly. A recent piece in the Times called him a provocateur, but that’s too strong a word—he’s more an overgrown hellion, and I say that with admiration. His needling, jeering pieces are like spitballs flung from the back of the classroom: you really, really want to ignore them and the puerile kid behind them, but now a gob of his saliva is on the teacher’s face, and it’s pretty funny.

“The Art of Plumbing” is the latest in a series of projects he’s launched through his Art Healing Ministry, an LLC designed “to channel the powers of art to alleviate major human physiological and psychological afflictions,” or, in other words, to goad his audience into seeing what a farce it is to claim that art is any kind of balm, that it serves any purpose. (See below for a helpful study conducted by the Ministry—“VARHEL, the Visual Art and Health Trial.”)

“The only philosophical idea that doesn’t seem to exist nowadays is skepticism,” he told me at his studio last month. “I now believe that art is total bullshit and nonsense. It’s one of the religious systems … what looks stupid and idiotic is most likely stupid and idiotic. We have to free ourselves from the chains of art. We’re always told it’s good for you. What’s good about it?”

“The only philosophical idea that doesn’t seem to exist nowadays is skepticism,” he told me at his studio last month. “I now believe that art is total bullshit and nonsense. It’s one of the religious systems … what looks stupid and idiotic is most likely stupid and idiotic. We have to free ourselves from the chains of art. We’re always told it’s good for you. What’s good about it?”

He told the Times something similar:

Art is not only physical pollution, it’s intellectual pollution. Spiritual pollution. I belong to the down-the-drain generation. We were promised salvation by art. I was a passionate believer, until I realized it was one of those allegiances, like spiritualism or theosophy. All of this kind of semi-religious teaching, like Mary Baker Eddy or Madame Blavatsky.

These are hardly new ideas, but Melamid, with his impish grin, is fervent enough to make you believe that he really wouldn’t care if every major museum in the world closed tomorrow. He speaks with the bemused outrage of a new atheist. To that end, there’s something agreeably simple in his operative urinal, which makes its points as easily and flippantly as those parodies of the Jesus fish you see on the backs of people’s cars. And to any artist who would accuse him of crassness and emptiness, he can say, My art removes human waste and conveys it to the sewage system of New York City. What does yours do?

Come, My Lad, and Drink Some Beer

Samuel Johnson’s portrait by James Barry.

From James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson. Johnson was born on September 18, 1709; Boswell wrote this passage in 1777, on the occasion of Johnson’s sixty-eighth birthday.

Thursday, September 18. Last night Dr. Johnson had proposed that the crystal lustre, or chandelier, in Dr. Taylor’s large room, should be lighted up some time or other. Taylor said, it should be lighted up next night. ‘That will do very well, (said I,) for it is Dr. Johnson’s birth-day.’ When we were in the Isle of Sky, Johnson had desired me not to mention his birth-day. He did not seem pleased at this time that I mentioned it, and said (somewhat sternly,) ‘he would not have the lustre lighted the next day.’

Some ladies, who had been present yesterday when I mentioned his birth-day, came to dinner to-day, and plagued him unintentionally, by wishing him joy. I know not why he disliked having his birth-day mentioned, unless it were that it reminded him of his approaching nearer to death, of which he had a constant dread.

I mentioned to him a friend of mine who was formerly gloomy from low spirits, and much distressed by the fear of death, but was now uniformly placid, and contemplated his dissolution without any perturbation. ‘Sir, (said Johnson,) this is only a disordered imagination taking a different turn.’

He observed, that a gentleman of eminence in literature had got into a bad style of poetry of late. ‘He puts (said he,) a very common thing in a strange dress till he does not know it himself, and thinks other people do not know it.’ BOSWELL. ‘That is owing to his being so much versant in old English poetry.’ JOHNSON. ‘What is that to the purpose, Sir? If I say a man is drunk, and you tell me it is owing to his taking much drink, the matter is not mended. No, Sir, ——— has taken to an odd mode. For example, he’d write thus:

“Hermit hoar, in solemn cell,

Wearing out life’s evening gray.”

Gray evening is common enough; but evening gray he’d think fine.—Stay;—we’ll make out the stanza:

“Hermit hoar, in solemn cell,

Wearing out life’s evening gray;

Smite thy bosom, sage, and tell,

What is bliss? and which the way?”

BOSWELL. ‘But why smite his bosom, Sir?’ JOHNSON. ‘Why, to shew he was in earnest,’ (smiling.)—He at an after period added the following stanza:

‘Thus I spoke; and speaking sigh’d;

—Scarce repress’d the starting tear;—

When the smiling sage reply’d—

—Come, my lad, and drink some beer.’

I cannot help thinking the first stanza very good solemn poetry, as also the three first lines of the second. Its last line is an excellent burlesque surprise on gloomy sentimental enquirers. And, perhaps, the advice is as good as can be given to a low-spirited dissatisfied being:—‘Don’t trouble your head with sickly thinking: take a cup, and be merry.’

Inherit the Earth

From Alfred Hitchcock’s film adaptation of Rebecca, 1940.

The moment of crisis had come, and I must face it. My old fears, my diffidence, my shyness, my hopeless sense of inferiority, must be conquered now and thrust aside. If I failed now I should fail forever.

―Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

It must be wonderful to be one of those pedestrians who own the streets. To be one of those people who walks where he likes with Ratso Rizzo–like entitlement, or, better yet, is gracious enough to usher a car forward when, in fact, the car has the right of way. Such people, of course, never give a timid wave of appreciation—a tacit “thank you for not killing me”—when a car lets them cross.

It must be wonderful never to assume your name has been left off the list, or that your card will be declined. It must be wonderful not to have the moment of anxiety, every time you pass through automatic doors, that they will not open. It must be wonderful not to cry every time someone slights you, and feel bruised for days afterward. It must be wonderful to be Rebecca de Winter, rather than her nameless successor.

Whether you consider Rebecca escapist fun, or an uneasy picture of the Electra complex run amok, or a masterpiece of Gothic storytelling, one thing is for sure: du Maurier paints one of the most accurate portraits of shyness in all of English literature. The narrator has none of Jane Eyre’s reserves and mysterious poise, none of the position and dignity of Jane Austen’s uncomfortable heroes. She is instead consumed by the particularly agonizing egotism that is shyness: a paralyzing self-consciousness that is reinforced by every slight, every harsh word, every reaction of the world, real and perceived. (I suppose I should add a spoiler alert here, for those unfamiliar with the plot of Rebecca.)

That she should ultimately triumph is not surprising. Shy characters always triumph. (They are, after all, created by writers.) But the ending of Rebecca is unusual. Usually a shy character has to change: his gifts are recognized and celebrated, he becomes the leader he was always meant to be. He comes out of his shell. Think of just about any children’s book and you’ll recognize the pattern. The heroine of Rebecca, however, manages to get everything she wants on her own terms. She routs her rival, gets her man, even sees the house that has oppressed her destroyed. Yes, she is good in crisis, but as any shy person can tell you, crisis is the easy part: it’s the challenges of day-to-day living that are difficult.

By book’s end, she has not changed, but, rather, reduced the world to the tiny scale with which she is comfortable. She and her husband are alone, he is dependent on her, and she is no longer faced with the manifold social ordeals that, conventionally, a heroine would master. It is hard to say who is redeemed and who’s corrupted. Or, indeed, whether anyone has changed at all. Is it the ultimate triumph, or a nightmare? That’s probably part of the appeal.

When you wave at a car, the wave seems to say, Thank you for not killing me. Maybe it is less silly than strutting around, holding up peremptory hands and pretending you have dominion over all the cars of the streets. But when you thank someone, aren’t you seizing the moral authority? By reminding them of their power, aren’t you asserting your own? Maybe not. Maybe it’s just good manners.

Stalking Seán O’Casey

Today is the fiftieth anniversary of Irish playwright Seán O’Casey’s death. Sam Stephenson tracks his appearances in W. Eugene Smith’s archive.

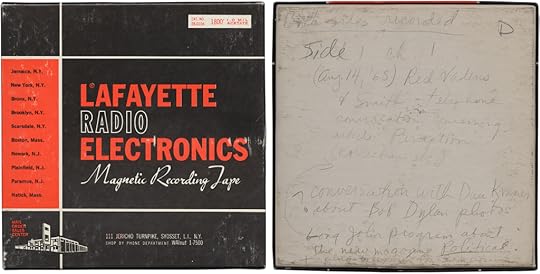

The original tape box for the reel containing the Red Valens phone call. On same reel, photographer Daniel Kramer is recorded in Smith’s loft discussing his photographs of Bob Dylan intended for Sensorium. Smith met Kramer in June 1965 when both were photographing Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited studio sessions. A Long John Nebel radio show is also recorded. The handwriting is an assistant’s, not Smith’s. Images courtesy of Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

On August 15, 1965, W. Eugene Smith was up late, as usual, in his dingy fourth-floor loft in the wholesale flower district, a neighborhood desolate after dark. He was working on the first issue of Sensorium, his new “magazine of photography and other arts of communication,” a hopeful platform free of commercial expectations and pressures. He was editing a submission by the writer E.G. “Red” Valens, whom he had met in 1945 when both were war correspondents in the Pacific. Despite the late hour, Smith decided to give his old friend a call.

Valens’s wife answered the phone just before the fifth ring. She’d been asleep. She gave the phone to her husband. He’d been asleep, too.

“Good morning,” said a groggy Valens.

“You don’t stay up as late as you used to,” joked Smith.

He then apologized for calling so late. Valens wasn’t irritated. He even resisted Smith’s offer to call back at a more reasonable hour.

Thirty-six minutes and nineteen seconds later, the pair said good-bye and hung up. We know this because Smith taped the phone call. When he died in 1978, this clip was among 4,500 hours of recordings he made from roughly 1957 to 1966.

After the discussion of Valens’s article concluded, the conversation turned to the habit of taking notes while reading. Smith said he couldn’t read one page of Henry Miller without taking three pages of dissenting notes. Valens said he could rank his library based on the number of notes he’d jotted in the margins of each book—the more notes, the more favor. Smith responded by expressing adulation for an Irish writer who had passed away the previous year:

That seeing, thoughtful soul Seán O’Casey causes me to be … when I run out of imagination or I’m just dead against a wall—I can’t function, I can’t think right, I have no probe, if I read O’Casey for a little while … I’m usually back to seeing and searching, and things start pouring out. Very few writers can do that to me. Faulkner can do it to some extent. O’Casey is my old standby. I always include a copy of O’Casey when I go somewhere on a story.

Valens then said, “That’s worth a short article next time you run out of ideas for an issue [of Sensorium]—‘O’Casey: The Traveling Man’s Boon.’ ”

Smith chuckled.

Valens then said, “No, I’m serious.”

Three weeks later, Smith’s financing for Sensorium fell through and another grand ambition was left unfinished. A more specific explanation of O’Casey’s impact on Smith’s photography never emerged, either.

* * *

In a letter to two editors at Holiday magazine in 1957, while pitching a layout of his extended work-in-progress on the city of Pittsburgh, Smith described the intended opus as “Tennessee O’Neill or Wolfe O’Casey.” The four names refer to three playwrights and a novelist, Thomas Wolfe, who also wrote several one-act plays. Throughout his life, Smith referred to literature and theater (and to music) as the most important influences on his photography, but he rarely provided references to specific works. His professed indebtedness bears a tinge of grandiosity and reveals, too, a general feeling of inferiority within the field of photography at that time.

Smith’s obsession with theater registered in other ways, too. Among them, his first daughter, Marissa, was named for a dancer he met while photographing a Broadway show in 1939. In much of his classic Life magazine work, especially 1948’s “Country Doctor,” his pictures resemble theater stills. He photographed the preparations and openings for original productions, such as Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire, and he produced two major photo spreads on obscure theater subjects for Life. When he began making voluminous photographs out his fourth-floor window in the late fifties, he called the frame his “proscenium arch.”

Smith spoke of his photography assignments as “stories,” as he did in the phone call with Valens. He would have been closer to the truth if he’d said, I always include a copy of O’Casey when I go somewhere on a poem. He never recognized or reconciled the difference between story and poem, or journalism and art, and the tension troubled him unconsciously.

Photojournalism—reporting from a field unseen by an audience—carried a legitimacy that was important to Smith. His father had been a business leader in Wichita, Kansas, and his mother a devout, converted Catholic; the expectations for young Gene were conventional. By age fourteen, he was working on assignments for local papers. When he was sixteen, he painted W. EUGENE SMITH, PHOTOGRAPHER on the side of his mother’s station wagon, signaling his desire to venture out for stories and be known for it. He retained the label of journalist for the rest of his life, long after his work had outstripped that field’s boundaries. In the margins of a book of writing by the sculptor Rodin, beside a passage about truth in art, Smith jotted, “This is the epitome of journalism.”

I recently came across a 1982 talk called “Impossible Stories” by the filmmaker Wim Wenders, in which he says, “In the relationship between story and image, I see the story as a kind of vampire trying to suck all the blood from an image. Images are acutely sensitive; like snails they shrink back when you touch their horns. They don’t have it in them to be the cart horses, carrying and transporting messages or significance or intention or a moral. But that’s precisely what a story wants from them.”

Wenders’s concern for the image helped me articulate my evolving feelings about Smith over the nearly eighteen years I have been studying his life and work. Smith resigned from Life magazine in early 1955, giving up a large salary and expense account. In doing so, he also gave up journalism once and for all. On his first freelance assignment in Pittsburgh, he befriended the young avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage, whose silent films and beliefs that language numbed the senses impressed Smith. His work moved further beyond journalism than ever, further beyond story, toward image and poetry. But he couldn’t shake the need for story in his public presentation. As a result, he strangled his extraordinary, lyrical Pittsburgh images by jamming them together on the page and inserting overwrought text. In one section comparing the most exclusive private club in Pittsburgh to a union beer joint, he added these words: “Yet at the core, down at the coiling depths of pulse and instinct, what difference here except in furnishing?”

I want to shake Smith. Hey, man, just let the images breathe. The image is enough.

* * *

I must admit that Wenders’s quote also gave me pause in my role as Smith’s biographer. I can see myself working to piece together a story from the detritus of his life—archives and memories and sometimes bread crumbs it feels he left behind on purpose. Too much effort to make a story from these fragments can suck the blood out of them.

When Smith’s archive was bequeathed to the University of Arizona, his library contained 3,750 books. Among them were two collections of Seán O’Casey’s plays, five of the six volumes of his autobiography, one essay collection, and two individual plays, Cock-a-Doodle Dandy and Red Roses for Me.

(Smith also owned about 25,000 vinyl records, including much of the spoken-word catalog of Caedmon Records, which means that it can reasonably be assumed that he owned that label’s 1952 recording of O’Casey reading selections from Juno and the Paycock and from two of the autobiographies).

Who knows how many O’Casey volumes Smith lost or gave away? A few jazz musicians who frequented Smith’s loft in the late fifties and early sixties were known to use his bookshelves like a lending library, with many books no doubt long overdue. Others would steal his things and hock them while Smith looked the other way.

A twenty-second comment by Smith about Seán O’Casey, in a dubiously recorded, nocturnal phone call in August 1965, led me down a rabbit hole. There are other references to O’Casey in the Smith annals, but none this alluring to me, the sympathy and patience for Smith demonstrated by Valens and his wife being the first thing, leading to the brief O’Casey monologue.

I now know a lot about O’Casey. I’ve read much of his work and I’ve reached out to O’Casey experts, such as James Moran, a professor of drama at the University of Nottingham and the author of a terrific study, The Theater of Seán O’Casey. There are ways to connect dots between Smith’s aesthetic impulses and O’Casey’s.

According to Smith’s first biographer, Jim Hughes, Smith had an affair with a young actress who read O’Casey aloud to him in 1949. Six of the books by O’Casey that Smith owned were published between 1944 and 1949, and thus would have been available during the affair. O’Casey had died less than a year before the 1965 taped phone call with Valens and the New York Times ran a three thousand-word obituary. There was even a Hollywood movie—Young Cassidy, from MGM—based on O’Casey’s autobiography that had been released earlier in 1965. The playwright reverberated in the culture then far more than he does today.

But what if Smith was more or less bullshitting about O’Casey? Slightly eager to grandstand in the lonely, sad-hour phone call? Knowing his tape was rolling, having enough ego to believe that a researcher would one day be listening?

Sam Stephenson is a writer and a partner in Rock Fish Stew Institute of Literature and Materials, a documentary enterprise based in Durham, North Carolina. He is the author of The Jazz Loft Project and is at work on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers