The Paris Review's Blog, page 660

September 24, 2014

The Cowboys of Europe, and Other News

From The Sons of Great Bear, a 1966 Romanian Western.

The Western is an integral part of the Hollywood canon, but European filmmakers weren’t about to let Americans have all the fun. Germany and France produced scores of Westerns, in part because “once you found a wide-open landscape vaguely redolent of the American West, they were relatively cheap to make.” But it was Italy that arguably perfected the European Western: “The Spaghetti Westerns, with their multiple aliases (Leone’s A Fistful of Dynamite is variously also known as Once Upon a Time ... the Revolution and Duck, You Sucker!), their badly-dubbed voices, their sweaty, sunburned close-ups and their loud, redounding music, were both gothic and grand guignol. They could also be incredibly sophisticated amid all the alarum.”

Today in pointless but strangely gratifying thought experiments: What would the longest book in the world look like? (“If there’s a new major character introduced every hundred pages or so, you’d have 100 billion main characters … ”)

A second novel is rarely greeted with the exuberance of a first. To help stop “Second Novel Syndrome,” the Whiting Foundation and Slate are compiling a list of under-recognized second novels from the past five years and reminding readers of their joys.

The radical linguists of the early twentieth century: “Historically, it was languages that were swept in with strong political, economic, or religious backing—Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, and Chinese in the Eurasian core—that were held to be the oldest, the holiest, and the most perfect in structure, their ‘classical’ status cemented by the received weight of canonical tradition … It was just over a century ago when a group of linguists made an effort to go beyond the language politics of imperialism and nationalism.”

Taking a cue from Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” a woman attempts to swim every (public) pool in Manhattan. (Unlike Cheever’s Neddy Merrill, she is not an alcoholic.)

September 23, 2014

Their Just Reward

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Librarian, 1562.

From The Librarian at Play , a collection of essays by Edmund Lester Pearson, published in 1911. Pearson was a librarian who wrote humor and true-crime books.

I looked and beheld, and there were a vast number of girls standing in rows. Many of them wore pigtails, and most of them chewed gum.

“Who are they?” I asked my guide.

And he said: “They are the girls who wrote ‘Lovely’ or ‘Perfectly sweet’ or ‘Horrid old thing!’ on the fly-leaves of library books. Some of them used to put comments on the margins of the pages—such as ‘Served him right!’ or ‘There! you mean old cat!’”

“What will happen to them?” I inquired.

“They are to stand up to the neck in a lake of ice cream soda for ten years,” he answered.

“That will not be much of a punishment to them,” I suggested.

But he told me that I had never tried it, and I could not dispute him.

“The ones over there,” he remarked, pointing to a detachment of the girls who were chewing gum more vigorously than the others, “are sentenced for fifteen years in the ice cream soda lake, and moreover they will have hot molasses candy dropped on them at intervals. They are the ones who wrote:

If my name you wish to see

Look on page 93,

and then when you had turned to page 93, cursing yourself for a fool as you did it, you only found:

If my name you would discover

Look upon the inside cover,

and so on, and so on, until you were ready to drop from weariness and exasperation. Hang me!” he suddenly exploded, “if I had the say of it, I’d bury ‘em alive in cocoanut taffy—I told the Boss so, myself.”

I agreed with him that they were getting off easy.

“A lot of them are named ‘Gerty,’ too,” he added, as though that made matters worse.

Then he showed me a great crowd of older people. They were mostly men, though there were one or two women here and there.

“These are the annotators,” he said, “the people who work off their idiotic opinions on the margins and fly-leaves of books. They dispute the author’s statements, call him a liar and abuse him generally. The one on the end used to get all the biographies of Shakespeare he could find and cover every bit of blank paper in them with pencil-writing signed ‘A Baconian.’ He usually began with the statement: ‘The author of this book is a pig-headed fool.’ The man next to him believed that the earth is flat, and he aired that theory so extensively with a fountain-pen that he ruined about two hundred dollars’ worth of books. They caught him and put him in jail for six months, but he will have to take his medicine here just the same. There are two religious cranks standing just behind him. At least, they were cranks about religion. One of them was an atheist and he used to write blasphemy all over religious books. The other suffered from too much religion. He would jot down texts and pious mottoes in every book he got hold of. He would cross out, or scratch out all the oaths and cuss words in a book; draw a pencil line through any reference to wine, or strong drink, and call especial attention to any passage or phrase he thought improper by scrawling over it. He is tied to the atheist, you notice. The woman in the second row used to write ‘How true!’ after any passage or sentence that pleased her. She gets only six years. Most of the others will have to keep it up for eight.”

“Keep what up?” I asked.

“Climbing barbed-wire fences,” was the answer; “they don’t have to hurry, but they must keep moving. They begin to-morrow at half-past seven.” […]

We hurried on to a crowd of men bent nearly double over desks. They were pale and emaciated, which my guide told me was due to the fact that they had nothing to eat but paper.

“They are bibliomaniacs,” he exclaimed, “collectors of unopened copies, seekers after misprints, measurers by the millimetre of the height of books. They are kept busy here reading the Seaside novels in paper covers. Next to them are the bibliographers—compilers of lists and counters of fly leaves. They cared more for a list of books than for books themselves, and they searched out unimportant errors in books and rejoiced mightily when they found one. Exactitude was their god, so here we let them split hairs with a razor and dissect the legs of fleas.”

In a large troop of school children—a few hundred yards beyond, I came across a boy about fifteen years old. I seemed to know him. When he came nearer he proved to have two books tied around his neck. The sickly, yellowish-brown covers of them were disgustingly familiar to me—somebody’s geometry and somebody else’s algebra. The boy was blubbering when he got up to me, and the sight of him with those noxious books around his neck made me sob aloud. I was still crying when I awoke.

The Art of the Obituary: An Interview with Margalit Fox

Photo: Ivan Farkas

In nearly twenty years and twelve hundred obituaries, Margalit Fox, a senior writer at the New York Times, has chronicled the lives of such personages as the president of Estonia, an underwater cartographer, and the inventor of Stove Top Stuffing. An instrumental figure in pushing the obituary past Victorian-era formal constraints, Fox produces features-style write-ups of her subjects whether they’re ubiquitous public figures, comparatively unknown men and women whose inventions have changed the world, or suicidal poets. (More on those below.)

I caught up with Fox in the Upper West Side café where she’s written two books, Talking Hands: What Sign Language Reveals About the Mind and The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code, the latter of which was published in paperback earlier this year. She was remarkably jovial and eager to clarify what it’s like to write about the dead every day. We spoke about the history of the obituary, her love of English eccentrics, and how it feels to call a living person in preparation for his or her eventual death.

Does the work you do change the way you think about death?

This work does skew your worldview a bit. We all watch old movies with an eye toward who’s getting on in age. I watch the Oscars memorial presentation and sit there going, Did him, did her, didn’t do that one. For obit writers, the whole world is necessarily divided into the dead and the pre-dead. That’s all there is.

How did you end up in the obituaries department?

I’d never planned for a career in obits. The child has not yet been born that comes home from school clutching a composition that says, When I grow up, I want to be an obituary writer. I started as an editor at the Times Book Review. It was wonderful to be around books and people that love books, but the job itself was copyediting. I was afraid that all they’d be able to put on my tombstone was “She Changed Fifty-Thousand Commas into Semicolons.” I started contributing freelance to the obituary section and ended up getting pulled in as a full-time writer.

How is your section different from other news sections at the paper?

Ninety-five percent of our job is writing daily obits on deadline. It’s impossible to have an advance written for all the pre-dead who we hope to cover, so we usually have to phone someone up to ask about a person or a subject we don’t know much about. Recently, one of my colleagues was heard running around the office going, Does anyone know anything about exotic chickens?! It’s that sort of thing.

How do people respond to getting a call from you within hours of the death?

In all my time doing obits, I’ve had maybe three families who refused to talk to me. In fact, families often reach out to us. If you’re a public figure who’s had a publicist during your working life, your publicist will do this one last act of publicity for you. One is eligible for spin control, even in death.

When I cold call a family, the minute I say my name and my paper, they’ll usually put the phone aside, turn to a relative and say, I’m on the phone with the New York Times! People tend to be grateful that their loved one is being publicly remembered.

Is it hard for you to navigate sources that are so regularly in a fragile state?

It behooves you, in purely human terms, to treat them as kindly as possible. That said, you don’t want to lull them into the sense that you’re a friend, an advocate, or some sort of a grief counselor. You do have people break down crying on the phone and you just wait patiently for them to regain composure.

In what ways do families try to control the narrative?

Families will say, Oh, be sure to put in that he died surrounded by his loved ones, or, Make sure you add that she touched the lives of everyone she knew. Those are things I never want to put in because they’re these Victorian clichés, but also because the obituary as a form has moved beyond protecting the family’s narrative.

How else has the form changed?

Well, for one thing, they’re a lot more fun to read. They used to be very formulaic.

Since they were considered boring, editors used to assign journalists obits as punishment. You knew someone was in trouble if they were chasing down obituaries.

That started to change with the great Alden Whitman, Mr. Bad News. He was famous for his advances. He’d do all this research and sit down with his subjects and they’d give him these very revealing interviews because they knew nothing would come out till they were gone. Douglas Martin, a colleague of mine who has been on obits longer than I have, started writing them in this charming, lively way, which has influenced my own style.

Our last few obits editors at the Times encouraged, where appropriate, a lighter, more features-style treatment. If you get one of these wonderful characters who took a different route to work one day in 1947 and invented something that changed the world, or one of these marvelous English eccentrics, there’s so much space to play. In the course of an obit, you’re charged with taking your subject from the cradle to the grave, which gives you a natural narrative arc.

Is there room for humor in today’s obituary?

I think so. The obits section is quite misunderstood. People have a primal fear of death, but 98 percent of the obit has nothing to do with death, but with life. There are maybe two sentences in there about when or where the guy died and with the rest, you let the person’s life guide the treatment. We like to say it’s the jolliest department in the paper.

Do you ever fight over covering particular people?

Only very gently. The thing about obits is there’s always enough to go around.

How do advance obits work?

Very often, in terms of advances, you hear that someone is hanging by a thread, you drop everything, you read all these books, do whatever you think you might have time to do, and then they live forever. The first advance I worked on was a big-deal academic, and he’s still around today. I wrote it almost twenty years ago.

We work on advance obits in the brief lulls between dailies, but it’s impossible to get them all done, so you’re left hoping people will live to be a hundred—otherwise it’s a mad scramble. That happened to me with Betty Friedan. She was among my pile of advance obits, but I hadn’t gotten started when I got a call that she had died. It was a Saturday; I rushed down to the office and frantically turned out 3,500 words. We got it in the next day’s paper. As I was running out of my apartment, I looked in the fridge and all I had was a leftover falafel, which was the only thing I had time to eat as I wrote it. I will forever associate Betty Friedan with cold falafel.

Can you talk about your use of euphemisms, either in the obituaries or in your dealings with families and close friends of the dead?

Rarely do I reach out to the subject of an advance obit, but when I do it can be difficult. The great Alden Whitman used to have these euphemisms he’d use, like, This is for possible future use, or, We’re updating your biographical file. I’ve used that successfully a few times. People absorb as much as they can handle.

The one thing that has changed, in terms of journalistic practice, is the cause of death. It’s much less euphemistically couched than in the past. When I was growing up, newspapers were very Victorian when it came to describing death. If you saw “short illness” it meant heart attack and “long illness” meant cancer. In small town papers where obits are written to protect the families, you still see that, but we’re much more straightforward.

How was suicide described?

Into the first half of the twentieth century you’d see, He died by his own hand. We say he committed suicide or he shot himself. We don’t go out of our way to be gruesome, but we’re obliged to report the cause of death even if it’s something stigmatized like AIDS or suicide.

Is it harder to get a confirmation on a suicide?

Occasionally, the family will confirm the death but won’t give the cause. One of the most heart-wrenching interviews I’d ever have to do was for a poet. I have maybe one suicide a year and they all seem to be poets. If I were an insurance company, I’d never write a policy for poets. This particular poet had shot himself, which I knew from other sources. But we’ve got to get the cause of death or the confirmation from someone close to the subject because many, many years ago we put an obit in the paper of someone who wasn’t dead. So now we’ve got an ironclad rule that a family member or close source has to confirm the death, usually by way of giving the cause.

I knew I’d have to call this poet’s wife and ask her to confirm the cause of death. There is nothing in Emily Post on making that call. It’s bizarre and horrific that as a stranger you’re calling someone cold and saying, Hello, you don’t know me, but I’m going to ask about the most painful thing in your life, which just happened yesterday, and I’m going to publish it where millions of people can see it. I called up, I took a deep, silent breath, I introduced myself and then—I’d normally never be this familiar with a source—I said, Honey, what the hell happened? God bless her, she told me. It was New York, in the summer, they had a bedroom air conditioner that was very noisy and, as his last act of tenderness to her, he made sure it was on, knowing the noise of the AC would cover the sound of the shot.

Is there an emotional toll for you in writing up those kinds of stories?

Suicides, particularly young suicides, are very, very painful. You can’t not be affected by having a story on your desk about someone in their twenties or thirties who has just shot himself. Very rarely is there an emotional toll, maybe once or twice a year. Happily, the vast majority of people we write about are people who’ve died in their beds in their eighties, having lived long, fruitful lives.

What happened with the obituary that was published before the person had died?

It was the obit of an elderly Russian dancer. One of our dance writers read in the European papers that she’d died. It was a Friday night, he couldn’t reach anyone in Europe, so he wrote that her death was reported by whatever paper he sourced the announcement from and the obit ran the next morning. We got furious calls from her family. Not only was she not dead, she was living in a nursing home in Manhattan.

Alex Ronan is a writer and abortion doula based in New York. She’s written for nymag.com, Adult, and Wag's Revue.

Mending Wall

Photo: Nigel Mykura

Colette once wrote that it’s impossible to write about love while you’re in it. (I’m paraphrasing.) I think the same is true of depression, although for different reasons. Love is too euphoric; depression is too tedious. It is not dramatic, it is not romantic. It is boring—to experience, to be around, to recollect. The rest of the time, when one is well, it is interesting only to the extent that a structurally unsound house is interesting to live in—you don’t think about it most of the time, and then occasionally you’re reminded to be careful, or to shore it up. (I can’t continue that metaphor because I have no idea how one goes about strengthening buildings. Mortar? Supports, probably.)

In the house where we grew up, the garage had a series of long cracks running up the stucco of its back wall. No one ever fixed it, but we were told sternly not to play near that wall. Instead, I would climb about twenty feet up a nearby pine tree, crawl onto the roof of the garage, and read there, or sometimes just run up and down the shingled peak, although I wasn’t habitually a physical risk-taker.

The only times my state of mind worries me are those times when Elves fails. Elves is the one thing that can always make me laugh—well, smile, anyway. The elves I mean are the ones in “Mending Wall,” wherein Frost’s speaker, walking the length of a crumbling fence with his hidebound neighbor, speculates about the forces that tear it down. “I could say ‘Elves’ to him.” I love the idea of someone saying “Elves” to someone else; having the thought of it.

When I would get sad and grim and joyless and my college boyfriend would see a cloud cross my face, he would sometimes lean over and whisper, “Elves.” He would say it in a very stentorian way, often at the strangest moments—on the Cyclone at Coney Island, or in the quiet car of a commuter train. It was always enough to jolly me out of myself for the moment. Often, just thinking it is enough. While that’s in the world, we’re okay, or we will be.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows?

But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Don’t Get Hot

Illustration: Tomia

An anecdote about censorship, since it’s Banned Books Week. Readers of today’s TPR know that our writers cuss with all the relish of a splenetic sailor who’s just stubbed his toe on shore leave. But such was not always the case. The magazine’s earliest editors were leery of salty language, and Terry Southern never forgot it.

Our latest issue features an editorial exchange between Southern and George Plimpton from 1958, when they were preparing Southern’s interview with Henry Green for publication. That interview features a now-classic aperçu from Green about the origin of his novel Loving:

I got the idea of Loving from a manservant in the Fire Service during the war. He was serving with me in the ranks, and he told me he had once asked the elderly butler who was over him what the old boy most liked in the world. The reply was: “Lying in bed on a summer morning, with the window open, listening to the church bells, eating buttered toast with cunty fingers.” I saw the book in a flash.

As Southern wrote to Plimpton, “Hot stuff, eh George? Well now you realize of course that the word ‘cunty’ makes the reply, gives it bite, insight, etc. I mean to say it simply would not do to rephrase it, ‘Lying in bed on a summer morning, with the window open, eating toast with fingers,’ would it?”

He’s right, of course—but if it seems he’s being unduly emphatic, that’s because The Paris Review had bowdlerized his words before, and he wanted to be absolutely certain it wouldn’t happen again. Southern’s short story “The Accident” had appeared in our first issue with a bit of dialogue as follows:

“Get Emergency,” he said. He spoke with a slight lisp. “They’ve got to get a foam-pump out here. Did you see this thing?” He gestured impatiently toward the burning wreck. Patrolman Stockton and the doctor considered him mutely for the moment, as if the lisp must dry away from the words one by one and let them drop in the dust at his feet all raw and revealed.

“Okay,” muttered Stockton, finally turning away, “okay, don’t get hot.”

Southern aficionados will raise an eyebrow at that last bit: “don’t get hot”? It’s not a very vigorous reproach—especially not when you bear in mind that this is the same guy who has elsewhere written of “tonguing dead Cong assholes with such incredible fervor and abandon as to finally lose consciousness.” What gives?

Well, the editorial powers that be had removed the words your shit from Southern’s dialogue. They feared repercussions from the U.S. customs officials, who were vigilant in their search for expletives—censorship was a going concern. Thus “don’t get your shit hot” became “don’t get hot,” which was not so hot at all, especially not to Southern, who hadn’t been consulted about the change.

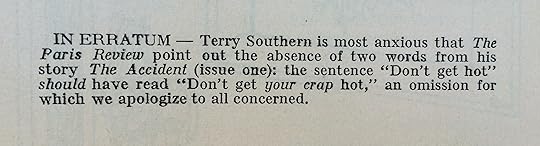

He was so dismayed to see his shit removed that a correction ran in the table of contents for our next issue, though, as you’ll see, it added insult to injury:

One can only imagine the torrent of imprecations that issued from the Southern tongue as he discovered crap where shit should’ve been.

To remedy the situation once and for all, if belatedly, I would like to present the unexpurgated sentence from “The Accident”:

“Okay,” muttered Stockton, finally turning away, “okay, don’t get your shit hot.”

And may the record show that cunty appeared in Green’s interview with no trouble, though Southern and Plimpton continued to swap jokes about it. Subscribe now and you’ll receive our Fall issue, which contains the gloriously profane (jock straps! razor fights! urinary tract worship!) and totally uncensored Plimpton-Southern correspondence.

[REDACTED], and Other News

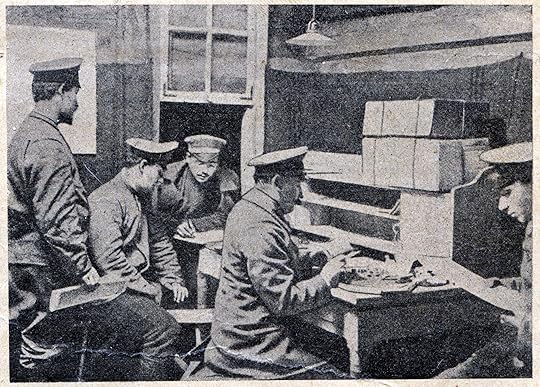

The censors of the Russian Empire. “Examination of correspondence from the theater of war by military censors,” an illustration from the journal Priroda i liudi, May 28, 1915.

What not to do during Banned Books Week: ban seven books. After a tense board meeting, a high school in Highland Park, Texas, has demanded its students stop reading The Art of Racing in the Rain, The Working Poor: Invisible in America, Siddhartha, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, An Abundance of Katherines, The Glass Castle: A Memoir, and Song of Solomon. “Parents and grandparents brought books flagged with sticky notes. They read excerpts of sex scenes, references to homosexuality, a description of a girl’s abduction, and a passage that criticized capitalism.” (Most of which you can find in a given issue of The Paris Review—lock up your daughters.)

Relatedly: What is censorship? “To dismiss censorship as crude repression by ignorant bureaucrats is to get it wrong. Although it varied enormously, it usually was a complex process that required talent and training and that extended deep into the social order. It also could be positive. The approbations of the French censors testified to the excellence of the books deemed worthy of a royal privilege. They often resemble promotional blurbs on the back of the dust jackets on books today.”

Things from which invisible ink has been made, through the ages: “The milk of figs, cows and nuts; lemon juice, orange juice and onion juice; saliva, urine, blood, vinegar, aspirin, and laxatives.” Oh, and a dormouse’s corpse … oh, and the display codes embedded in porn images …

Talking to Emmanuel Carrère—“the most important French writer you’ve never heard of,” unless you’ve read the Art of Nonfiction No. 5—about his new book Limonov, which comes out next month: “In the manner of Truman Capote … Carrère has waited, with the patience of a deer hunter, for the true story that would not only illuminate aspects of his own life, but also exemplify the puzzle of the post–cold war west.”

“The internet gives us everything that writing does not: it gives us what we dream about when sitting alone at our desks: contact with our tribe and the sense that we’re in a community … The internet reminds me of smoking—which I gave up almost twenty-seven years ago—but whenever someone talked about cancer or heart disease it made me want to light up.”

September 22, 2014

Double the Pleasure

New York: this week, you can catch our editor, Lorin Stein, in conversation with two great writers, at two different independent bookstores, on two separate occasions.

First, on Wednesday at seven thirty, he’ll talk to Donald Antrim at Brooklyn’s Greenlight Bookstore, about Antrim’s new story collection, The Emerald Light in the Air: “No one writes more eloquently about the male crack-up and the depths of loneliness,” says Vanity Fair, “than Donald Antrim; the stories in The Emerald Light in the Air, hopscotching between the surreal and ordinary, comic and heartbreaking, are dazzling.”

Then, on Thursday at seven, join us at McNally Jackson, where Lorin and Ben Lerner will discuss the latter’s new novel, 10:04, which Maggie Nelson has called “a generous, provocative, ambitious Chinese box of a novel … a near-perfect piece of literature, affirmative of both life and art.”

We hope to see you there!

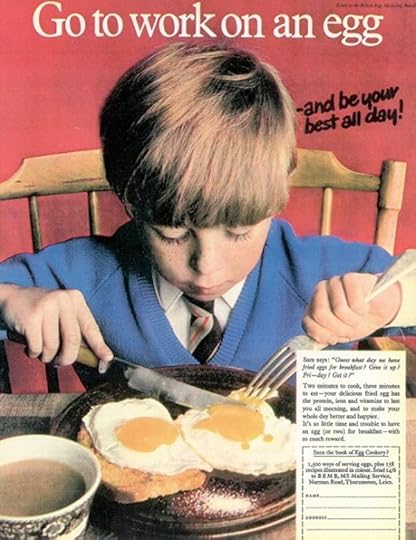

Go to Work on an Egg

Before she made a living as a novelist, Fay Weldon, who’s eighty-three today, was a copywriter “at O&M, a copy group head in charge of the Little Lion egg account, first-generation IBM computers, and goodness knows what else.” As she tells it, her crowning achievement there was the slogan “Vodka makes you drunker quicker”: “It just seemed to me to be obvious that people who wanted to get drunk fast needed to know this.” Her superiors disagreed—god knows why—and the motto never saw the light of day.

What did see the light of day is “Go to Work on an Egg,” a masterly double entendre that served as the catchphrase for the aptly named British Egg Marketing Board. Weldon managed the ad team that coined the phrase, and proof of her handiwork abounds. On YouTube you can find a series of “Go to Work on an Egg” meta-advertisements in which an increasingly indignant Tony Hancock—a famous British radio and TV personality—bemoans that his career has come to this. “Ladies and gentlemen, owing to the present state of the theatrical profession, I have with great reluctance been forced to accept a job as a supporting actor to a lady doing a commercial for eggs.”

That lady is a stereotypical housekeeper, a brassy harridan who squawks, “Eggs is easy. Eggs is cheap! Full of proteins, and what’s more, they helps ya to face up to the day.” Success, we learn, is egg-shaped. Happiness is egg-shaped. Vitality is egg-shaped, too. Another rendition features Hancock, having “sold his soul” to the egg harridan, going virtually insane as her egg maxims reverberate through his mind; he even sees them on the wall of his bedroom. I admire the ambivalence of these ads—far from an enthusiastic shill, Hancock is perhaps the most embattled, indifferent spokesman I’ve ever seen. He doesn’t even seem to particularly like eggs. (He always takes them soft-boiled and à la carte, which may be part of the problem.) He’s only enumerating their benefits because he needs the work, and because, well, eggs are pretty good, and cheap, if you think about it ...

Looking back on her advertising career in 2002, Weldon wrote,

Odd how moving those early ads are, both in the press and, from the beginning of the sixties, on TV. They show an age without cynicism, without haste. Mother and wifely love triumphant and unquestioned: the appreciation of a family all-important … And yet, the very insistence in the ads that women hardly existed in their own right—but were there to serve children and husband, and let that be enough for them—no doubt contributed to the surge of feminism in the seventies and the profound changes in our society we've seen since then.

The “Go to Work on an Egg” slogan persisted in various guises until 2007, until the UK’s Broadcast Advertising Clearance Centre banned pro-egg ads “for failing to promote a balanced diet.” Weldon told the Daily Mail at the time, “I think the ruling is absurd. We seem to have been tainted by all the health and safety laws. Eggs were enormously healthy compared to what people were eating in the fifties and a great form of protein. If they are going to ban egg adverts, then I think they should ban all car adverts because cars really are dangerous—and bad for the environment.”

Charm

Detail from the cover of The Polly Bergen Book of Beauty, Fashion and Charm (1962)

When I was in tenth grade, I went through a phase when I cut class all the time. Not in a fun way—I never told any of my friends what I was doing—or to be rebellious. In retrospect, I think I must have been depressed; I simply could not face other people, or think beyond hiding myself in the library in a small nook on the second floor. For some reason, I always read The Polly Bergen Book of Beauty, Fashion and Charm, from 1962.

Polly Bergen died this week at the age of eighty-four. She was a polymath: an actress, singer, professional sophisticate, and (evidently) advice-giver. I knew none of this when I first picked up the book—why it was in my high school's library is another open question—but quickly I learned about her country-music career, her success in films like Cape Fear, and, of course, the development of her signature look, which involved big glasses and a pouf of a dark coif. It’s not hard to see what attracted me; the cover features Bergen, in evening dress, peering out seductively from behind a cellophane curtain.

Bergen would go on to be a successful entrepreneur—she sold makeup, jewelry, and shoe lines—and an outspoken feminist. She was what was known as a “big personality” in the day, and was open about her ambition and strong will. Her recent obituaries have been laudatory, and quite moving.

In tenth grade, I didn’t know anything about Bergen’s life past 1962, but during those few months of intense intimacy, her brassy sixties-era confidence was deeply comforting. I liked how definite she was about beauty tips, the elements of charm, and the importance of establishing a “type.” I remember her writing that she was really only herself in her glasses; I liked that this was an essential part of her glamor.

One day, I got caught by my favorite teacher. He had checked with the nurse’s office and found that I had lied about being sick. (I had been in the library, reading The Polly Bergen Book of Beauty, Fashion and Charm.) This man was a wonderful teacher; I loved his history class, and I knew he liked me, too, and thought I was smart. I know exactly why I had skipped his class that day. I was ashamed; I had not wanted him to see me depressed and unprepared and as I really was. I wanted to keep his good opinion. “Why did you lie to me?” he said, seeming really hurt. And I didn’t know what to say. Of course, he didn’t like me after that.

Talk About Beauties

The lost recordings of a phantom musician.

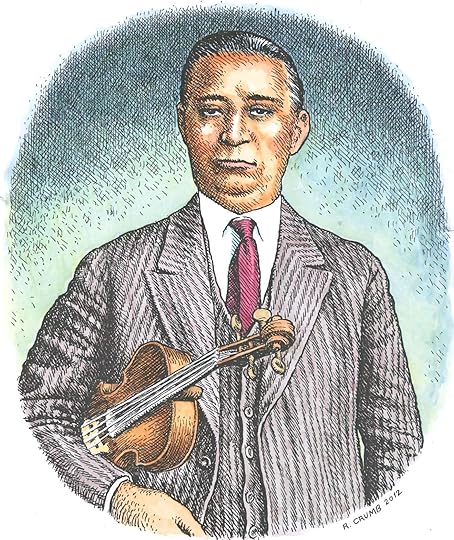

Alexis Zoumbas, illustrated by R. Crumb.

The text printed on the label of the Greek 78-rpm disc translated as “Alexis Zoumbas ~ violin, accompanied by young men of the Epirot village of Politsani.” Its significance, and the meaning behind its very existence, stymied all speculation. No one had heard what was etched into these grooves since they’d been pressed—the Greek title for the song was untranslatable, and the recording itself was undocumented, hushed into being for no perceptible reason other than to come into my possession.

A week before this record arrived at my post office, I’d finally untethered myself from Zoumbas and his recorded legacy. After two years of focused inquiry, I’d finished work on Alexis Zoumbas: A Lament for Epirus, 1926-1928, a collection of his recordings. I’d let go. But any comfort I found in that was lost when this disc came into my life.

The 78 rpm record was the dominant medium of auricular permanence and commerce for more than fifty years. These fragile vessels of sound are coveted by collectors who, like myself, have developed a precise yet vaguely sexual phraseology to describe their physical condition. This Zoumbas disc, for instance, was in excellent condition, but with a tight hairline crack and a slightly enlarged spindle hole.

And what of its artist? Alexis Zoumbas was a phantom musician, a violinist. Born in the hinterlands of Epirus, Greece, in 1883, he immigrated to New York City in 1910 and died practically unknown in Detroit in 1946. The myth surrounding his life maintained that he’d fled Greece after murdering his landlord, and that he himself had been gunned down by a jealous lover. Drawn in by his music and intrigued by these stories, I become obsessed with his life. I traveled to his home village, Grammeno, to interview his two surviving nephews, Michalis and Napoleon Zoumbas, both retired musicians in their eighties. In Ioannina, the capital of Epirus, I unearthed biographical documents; in the U.S. I found immigration and naturalization papers, as well as a draft card and a death certificate. This trail of evidence, dispersed across continents, corrected the narrative of this powerful musician’s life. He did not kill his landlord, and he wasn’t offed by a jilted lady friend—those were apocryphal stories created to elevate his musical status and cultural legacy. Zoumbas had entered into the elite mythical realm reserved for more well-known American prewar musicians like the Delta bluesman Skip James and the Appalachian banjoist “Dock” Boggs, majestic artists surrounded by imaginary rows of corpses, stacked like cordwood, coolly dispatched in their dreams and in the stories told about them.

My fixation with Zoumbas—especially with his bow stroke and what it said about him, about his movement from traditional northern Greek melodies to an idiosyncratic expression of immigrant artistry—sprang from an earlier fixation with instrumental songs from Albania and Epirus. Zoumbas came from a musical tradition where the violin rarely led the entire performance and where the repertoire scarcely varied from one small village to the next. When he moved to New York in 1910, he found he could take this very old body of folk music and imbue it with his own story: his experiences of a strange land and his raw emotions. Zoumbas longed for Epirus, and this longing combined with his virtuosity to produce recordings of unfathomable misery and pathos. His music was colored by the Epirot concept of xenitia—a profound yearning for one’s home soil, and a corresponding ache for the emigrant by those left behind.

Villagers and musicians from Epirus believe that a unique body of melodies, played principally with the clarinet and violin, give psychological healing to all those who listen to them: a harmonic panacea. The two tunes most strongly identified with Epirus are the mirologi and the skaros, both improvised pentatonic instrumentals, with free melody and meter but regionally defined tonal emphases and embellishments. They’re ancient and primal. The mirologi was originally a vocalized funerary lament, sung over the body or next to the grave of the deceased for several years until the earth consumed the flesh; after that, the bones were exhumed, bathed in wine, and placed in the village. Mirologi are found throughout ancient Greek literature, in the epic poems and tragedies. At some point, the keening of mourning women was transformed into an instrumental that’s central to Epirot music and culture. This dark, melismatic piece is played at the beginning and at the end of the traditional feast-dances in Epirus, the paniyeria.

A skaros is a shepherd’s song, as old as the mirologi. The shepherd would play a special skaros with his flute to calm and gather his herd, essentially drawing them together in a hypnotic state. An especially well-crafted skaros, played in Epirus with the clarinet and violin, produces a kind of viscerally felt introspection.

I came to discover Alexis Zoumbas through two old 78 discs, one containing a mirologi and the other a skaros. Upon acquiring his Epirotiko Mirologi, “A Lament for Epirus,” I played it in my record room and a dark vastness opened; I wanted to uncover the instinct that created this music, this expression of despair. While his violin keened and wept, the horsehair on the bow of the contrabass maintained constant contact and dark tension, a tonal anchor. Zoumbas’s mirologi was the sound of a looming asteroid right before it smacks into Earth, ending all life and hope.

* * *

A map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich Kiepert, 1902.

As I unpacked his life and constructed a narrative, Zoumbas had inevitably taken on a corporeal form. The trek to Epirus to gather oral history from his family and village, the dossier of vital documents from the U.S. and Europe, and the shelf containing nearly all of Zoumbas’s twenty-odd instrumental discs seemed to imply closure. But then this record came.

An Albanian American and second-generation Bostonian, Steve John, had been graciously feeding me duplicate 78s from his collection. Three days after I’d finally finished the Zoumbas compilation, Steve called to inform me that he had acquired a stack of Albanian records and a very curious Greek disc, a twelve-inch record on the Me-Re label, established by an Albanian musician, Ajdin Asllan. I had acquired a 1946 catalog of the Mi-Re label a few days earlier and had scarcely thumbed through it. Now, looking up the disc, I shuddered in disbelief: Zoumbas was listed in a catalog the very year he died, sixteen years after his last documented recording. Typical of the time, the listings for the records were misspelled in Greek, so the title of this one was untranslatable. Only when I got the disc in my trembling hands did I realize that someone, probably Asllan, had etched the proper name of the song and the date of recording into the dead wax. It read: “O MENOUSIS (10-2-43).” After washing the disc, I glided the stylus into the groove and the old Greco-Albanian murder ballad echoed forth after having been unheard all these years. Slow, stark, and funereal:

Menousis, Birbilis and Resul-aga

Met at a taverna to eat and drink.

While eating, while drinking, while making merry,

They drifted into talk about beauties.

“A beautiful wife you have, Menous-aga.”

“Where did you see her, how do you know her and mention her?”

“I saw her last evening at the well—she was drawing water

And I gave her my kerchief and she washed it.”

“If you met her and you know her, tell us what she’s wearing.”

“A silver petticoat with golden coin.”

Menousis, drunk, went home and stabbed her to death.

In the morning, sober now, he wept her a lament:

“Rise, my duck, rise, my goose, rise, my blue-eyed one,

Rise and dress, put on your jewelry and join the dance,

That young men may see you and wither,

That I, poor man, may see you and rejoice in you.”

It was dizzying to hold the last disc, the only known copy, of Zoumbas in my hands, but perhaps it was more unnerving that this was barely a Zoumbas recording. The voices of four or five young men from Politsani—a village that’s almost wholly Greek Orthodox and Greek speaking, though it’s located about twenty miles within Albania’s border—dominate the recording. They sing in the iso-polyphonic style of Epirotes and Southern Albanians, in which one or more vocalists deliver the main melodic line while another singer or two add commentary, weaving in and out, creating dissonances and increasing the tension of the narrative. Another one or two people provide a constant drone an octave below the tonic key of the piece: a low, dark center. This tapestry of sound has its roots in Byzantine hymnody and Balkan epic song. Zoumbas’s violin and probably Asllan’s clarinet punctuate each verse, nothing more.

Questions flowed from this record, suggesting narrative detours that I must explore. Why, for instance, did Asllan choose to label and list this disc as a Zoumbas record when Zoumbas was no longer famous in the forties? His music, outside of Epirus, was too old-fashioned, reminiscent of a homeland that few longed for. Perhaps Asllan recorded Zoumbas out of friendship, maybe as a last glorious gesture before the void took everything away but this brittle piece of shellac. Because of rationing for the war, this disc wasn’t pressed until early 1946, implying either that Zoumbas saw and heard it right before he died—on February 7, 1946—or that he never saw it at all. And why had this disc found me? How had something so rare, so fleeting, ended up in my hands at exactly this time?

I’d thought earlier that the collection I produced was a proper lament for Alexis—he had never been mourned, and he died in a state of xenitia, yearning for his home soil. But as I sat alone in my record room, the needle trapped in the dead wax of the run-off groove, I realized that having stitched up a new suit of flesh for this specter meant I’d always have to look after him. In Epirus the dead are always with the living: they see them, they long for them, they care for them.

Lyrics translated by the Greek poet Demetrios Dallas.

Christopher King is an auricular raconteur and sonic archeologist. He produces CD and LP collections of music from old 78s through his studio, Long Gone Sound Productions, in Virginia.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers