The Paris Review's Blog, page 656

October 8, 2014

The Will to Believe

Sitting in on the 2014 Objectivist Conference in Las Vegas.

The Venetian. Photo: Dietmar Rabich

Even on a Monday morning at eight A.M.—an hour ripe for sober reckoning—the greatest lie of Las Vegas endures undiminished: if you keep playing, you’ll eventually beat the house. As I strolled through the Venetian, I saw the familiar ring of mostly young men crowding the aprons of a long line of craps tables. If any moment in Vegas should lend itself to second thoughts for these men, it would’ve been this one, the morning after a boozy weekend of debauchery. Yet the only concession to the occasion were the mimosas hanging pendulously over the Pass Line.

I was late for a different sort of spectacle, so I didn’t stop to watch. The Venetian, by some measurements the largest hotel in the world, had set aside a tranche of its 289 “meeting rooms” for the annual summer conference of the Ayn Rand Institute, an organization founded in 1985, a few years after the death of its namesake, with the express mission of fostering “a growing awareness, understanding, and acceptance of Ayn Rand’s philosophy.”

Open conferences are admirably egalitarian, which makes them something of an awkward format for discussing Objectivism, the name Rand choose for her canon of unalloyed elitism. “The man at the top of the intellectual pyramid contributes the most to all those below him, but gets nothing except his material payment, receiving no intellectual bonus from others to add to the value of his time,” her avatar, John Galt, declares in Atlas Shrugged. Meanwhile, “the man at the bottom who, left to himself, would starve in his hopeless ineptitude, contributes nothing to those above him, but receives the bonus of all of their brains.”

One need not be an honors geometry student to understand where on this pyramid most of us must fall. Throughout her writings, which began with allegorical novels and evolved into a miscellany of short works—speeches, essays, newsletters, and even, for one year, a weekly column for the Los Angeles Times—Rand was an evangelist for an aristocracy of talents. She characterized her aesthetics as “a crusade to glorify man’s existence” and the essence of her philosophy as “the concept of man as a heroic being,” descriptions which, if they mean anything, would lead one to believe an assembly of her acolytes might resemble a cross between a meeting of Phi Beta Kappa and an afternoon among the bodybuilders at Venice Beach.

I wondered as much as I wound my way through the gilded alleys of the cavernous conference center. A floor beneath my destination, I passed the abandoned belvedere of the Martial Arts Industry Association, one of the many groups with scheduled summits that day. Later on, it would provide the only sighting of aggressively muscled men, who were conspicuously lacking at the Objectivist Conference—or OCON, the favored shorthand for attendees.

At first glance, they were an unassuming lot, whose sleepy eyes and towering lattes suggested they were as susceptible to the seductions of Sin City as most anyone else. They were a little older than I had expected and, more surprising still, there weren’t very many of them, eighty perhaps for the first session, an acroamatic overview of Ayn Rand’s philosophy. More arrived as the day progressed, but not enough to overcome the initial impression of a room full of empty seats, and not nearly enough for an interloper to feel anonymous in the least.

“Is this your first OCON?” a well-appointed woman with two cell phones asked me shortly before an afternoon session. The question was clearly rhetorical, coming as it did from someone who made it plain to me that she looked forward to the conference in much the same way we all anticipate certain events that embellish our identities. She wasn’t alone. One speaker shared that he had about twelve people he considered family. “Some are in this room right now,” he said, “and there’s only one of them biologically related.”

Such moments make me hesitant to call the conference participants “true believers,” not so much because the term is misapplied—given that one panel was titled “Objectivism Is Radical,” I suspect most of them would embrace it—but because it fails to capture what struck me about them. They seemed less like ideologues impatient for Galt’s Gulch than the graying registrants of a reactionary class reunion.

The effect was one that is common to any routine gathering that riffles a creedal code. The revealed word is best left unspoken, for demystification comes cheap: to the grizzled comrade sipping cold coffee between plenary sessions of the Sixth Congress of the Communist International, even Capital must seem a little less enchanting. The old villains remain—and at OCON, the welfare state, Obama, and liberal intellectuals all came in for a drubbing. But neither they, nor the cause they threaten, have the same sense of urgency. Familiarity may breed contempt, but it also breeds complacency.

And that’s why the first timers, perhaps a quarter of the crowd, were the more intriguing group to watch. Some of them were the high-school and college kids the Ayn Rand Institute determinedly cultivates, but others seemed to have recently “found” Rand’s work. For them, The Romantic Manifesto, The Fountainhead, and especially Atlas Shrugged still had the dazzling immediacy of a message that is extraordinary and half explained. They mobbed the microphone at the end of each session, eager to ask questions that inevitably involved a “coming to grips” with Rand’s philosophy.

Some were simply matters of implementation. At an education panel, a slight young man recounted the indignity of having to write a paper on Gravity’s Rainbow. He quickly determined that Thomas Pynchon was unworthy of his time—“he has no plot, there is no theme, there is no reasoning”—but when he shared his conclusion, he found himself sent to the principal’s office. There, he had a minor epiphany: what is right and what is expedient aren’t necessarily one and the same. Ambitious to get into a good college, he simply had to know: What would Rand do?

Some variation of that question was most common among the neophytes, but the more compelling inquiry came from those who ached because they already knew the answer. At the final session I attended, “How to Be an Impassioned Valuer,” a man wanted to know what you should do if you had lost the time to pursue the things you value. The question wasn’t exactly well thought out, and it seemed a little strange coming from someone who looked to be in his thirties, but everyone knew what he was getting at. The problem was not a matter of time but competence. What if you knew what you wanted to accomplish with your life, but you also knew in your heart of hearts that no matter how long you applied yourself, no matter how hard you tried, you could never do it, not in any way that would ever seem exceptional, not to you and certainly not to Ayn Rand? Could you live with yourself consistent with an elitist philosophy?

You couldn’t. That’s the honest answer, which is why Objectivism is the most American of philosophies. Its appeal, like that of Las Vegas, ultimately relies on the most irresistible self-deception of them all: You are never not exceptional. Only not yet.

John Paul Rollert is a writer in Chicago. His work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Boston Review, and the New York Times.

The Camera Wins by Being Honest

Image via X-Tra

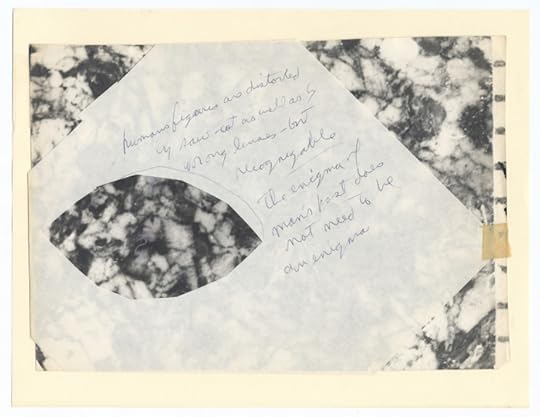

Richard Sharpe Shaver is best remembered as a controversial sci-fi writer—in the late 1940s, his pieces in Amazing Stories made outlandishly specific claims about evil ancient civilizations, and it became progressively clearer that Shaver didn’t regard these stories as fiction. Toward the end of his life, Shaver spent his time elaborating an arcane theory about “rock books”; in certain stones, he avowed, one could find intricate pictographic texts inscribed by the hyperadvanced races of millennia past. As the art quarterly X-Tra has it, Shaver believed he’d begun to decode the texts of “a whole prehistoric Atlantean library”:

Shaver accessed the rock books by cutting through stone with a saw to reveal a world of imagery within the fissures. “Humans figures [sic] are distorted by saw-cut as well as by wrong lenses—but recognizable. The enigma of man’s past does not need to be an enigma.” This statement, handwritten in blue ball-point pen on thin typewriter bond, floats to the right of an oculus cut into the paper, which reveals beneath a photograph of what appears to be a random black and white pattern. In fact, Shaver believed the pattern was a holographic picture created thousands of years ago by an advanced ancient technology.

It can feel voyeuristic to dwell on the remnants of lunacy—like gaping at the crazies on the subway—but Shaver’s devotion and imagination provoke a strange empathy. As Brian Tucker writes in an excellent summary for Cabinet, “Despite poverty and virtually unremitting scorn, Shaver continued this work until his death in November 1975.” A few years ago, Tucker curated an exhibit including some of Shaver’s papers and theories:

The pictorial content that Shaver identified in these rocks is dense and complex. Different images reveal themselves at every angle of view and every level of magnification; pictures mingle with ancient graphic symbols and typography in what he called “the most fascinating exhibition of virtuosity in art existent on earth” … Discouraged by critics who charged that the figures pictured in his paintings were mere fabrications from his own imagination, he eventually abandoned painting in favor of the relative objectivity of photographic documentation. In an unpublished manuscript, Shaver writes, “If I hadn’t been an artist most of my life, I would have realized that people will believe photos, and won’t believe drawings or paintings … The camera wins, by being honest … which doesn’t say much for artists’ honesty, I guess. We try … but people think we lie.”

Earlier this year, the Morgan Library included some of Shaver’s photos in its exhibition “A Collective Invention: Photographs at Play”; a write-up at Hyperallergic has a number of examples. Shaver’s descriptions of his pictures are bewilderingly opaque, with lots of cultural references and an occasional erotic undercurrent. “Once you get accustomed to high-contrast rock-photo prints,” he writes below one photo, “they have the same charm as a Beardsley black and white drawing, the same erotic fascination … ” He compares another to the Lone Ranger’s mask, and notes, “The mask is speaking to a larger female with very large breasts.” The back of another photo says simply, “Mer feet.” (“We think of mermaids as a mad sort of myth, but in fact they were our direct ancestors.”)

“It only seems confusing,” Shaver tries to explain of the texts. “The confusion is because it is four way and has to be separated into one way.” But this you could write off as garden-variety insanity: the frustrated condescension, the seeming obviousness of it all. For me, Shaver is most affecting when he seems too daunted by his discovery to begin to know how to comprehend it: “What to do about universal ignorance of man’s beginnings is too much problem [sic] for me. I can’t even sell a rock book.”

If you want to steep yourself in Shaver lore, check out Shavertron, an online magazine that bills itself “Your Only Source of Post-Deluge Shaverania.”

What Is an Essay, Anyway? and Other News

A portrait of Michel de Montaigne, whom you can blame in part, maybe, for all these “essays.”

Essays—essais, essayes—what are they, how are they, where did they come from, why can’t we seem to settle on the meaning of them, is Montaigne to blame for all this, or Francis Bacon or maybe King James, and what’s the meaning of all this “attempting” anyhow … John Jeremiah Sullivan aspires (don’t make me say essays) to find out.

Horace Engdahl, who helps to judge the Nobel Prize in Literature, laments the “professionalization” of writing in the West: “I think it cuts writers off from society, and creates an unhealthy link with institutions … Previously, writers would work as taxi drivers, clerks, secretaries, and waiters to make a living. Samuel Beckett and many others lived like this. It was hard—but they fed themselves, from a literary perspective.”

Relatedly: “A growing number of biographers and historians are retrofitting their works to make them palatable for younger readers … And these slimmed-down, simplified and sometimes sanitized editions of popular nonfiction titles are fast becoming a vibrant, growing and lucrative niche.”

Zadie Smith on a certain famous populous island: “Manhattan is for the hard-bodied, the hard-minded, the multitasker, the alpha mamas and papas. A perfect place for self-empowerment—as long as you’re pretty empowered to begin with. As long as you’re one of these people who simply do not allow anything—not even reality—to impinge upon that clear field of blue. There is a kind of individualism so stark that it seems to dovetail with an existentialist creed: Manhattan is right at that crossroads. You are pure potential in Manhattan, limitless, you are making yourself every day.”

“An intellectual is a person who is mainly interested in ideas. I am an aesthete—a person who is mainly interested in beauty. Nowadays the word aesthete carries with it the musty reek of high Victoriana. Still, there remains no better word to describe the way certain people—people like me—view the world.”

October 7, 2014

All Aboard L’Armand-Barbès

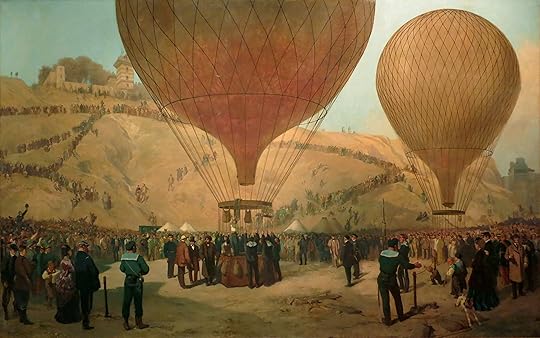

Jules Didier and Jacques Guiaud, L’Armand Barbès, 1870, 1914

Say you’ve got to skip town in a hurry. Maybe you owe somebody a lot of money; maybe the mayor’s daughter is in love with you and you’re below her station; or maybe it’s 1870, the Franco-Prussian War is on, and you have to ditch Paris because it’s under fierce siege and you’re the minister of the interior. In any case, here’s what history advises:

Flee in a hot-air balloon.

Léon Gambetta did it on October 7, 1870. Worked like a charm.

Okay, Paris ultimately lost the war, so “worked like a charm” may be overstating things, but still—Gambetta lived, didn’t he? He did. He became a prominent statesman.

At the time of his spectacular escape, Paris had been shelled by the Germans and Napoleon’s empire had fallen; Gambetta helped to improvise a new government and advised running it from someplace other than the capital, given the city’s precarious condition. A delegation left for Tours to organize the resistance, but Gambetta himself had to be sure to elude capture by the Prussians.

The safest way, against all odds, was by balloon: couriers had been delivering the mail to Paris that way with great success. And so they smuggled him out on the sumptuously named (if not sumptuously appointed) Armand-Barbès, one of some sixty-six balloons. He made it to Tours intact and resumed his post with vigor.

After this comes the part where the French lose anyway, but let’s skip that and wonder instead how Gambetta felt up there, in transit. I mean, I’m sure he was terrified, at least partially—his capture would be the end of him—and yes, there must’ve been a good bit of patriotism coursing through the old veins, but I hope he took a deep breath and saw the bigger picture, saw himself wafting into the history books on a hot-air balloon, Prussians cursing the sky and stomping on their hats.

And how, once he’d reached safety, could he find it in himself to talk about anything else?

“Hello,” I would say by way of introduction for the rest of my life. “It is I, the man who fled Paris by balloon. No, no, remain seated. Hold your applause.”

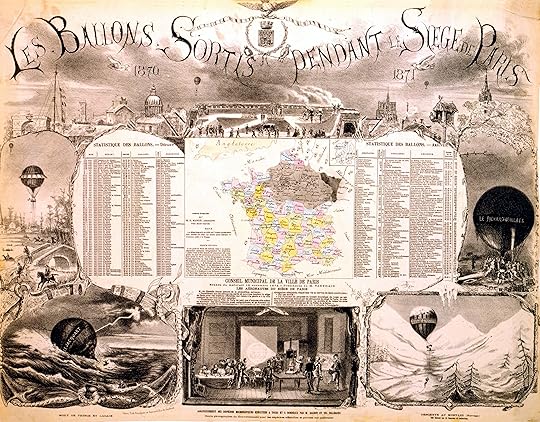

A broadside about ballooning during the Siege of Paris, 1870-1871, with a list of balloons that left the city.

The Notion of Family

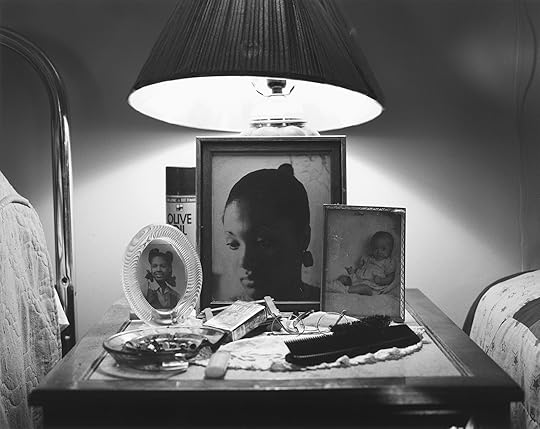

Aunt Midgie and Grandma Ruby, 2007.

LaToya Frazier’s first monograph, The Notion of Family, documents the decline of Braddock, Pennsylvania—a once-prosperous steel-mill town that employed generations of African American workers—alongside the hardships of Frazier’s family, who grew up there. Issues of class and race underscore the mostly black-and-white photographs in the collection, which is arranged as a kind of family album: intimate, collaboratively produced portraits of Frazier and her mother in mirrors and on beds, are presented with derelict scenes of collapsed buildings, vacant lots, and boarded-up stores.

Frazier provides short texts with each image—wistful snippets of memory and anecdote merge with facts and statistics. Illness is nearly a constant. As Laura Wexler points out in an accompanying essay, Braddock’s hospital, which eventually housed the town’s only restaurant and therefore became its de facto meeting place, “is as much or more a fixture in this album and this family than the school, the factory, the library, the market, the taxi stand, the pawnshop, or any other institution.”

Home on Braddock Avenue, 2007.

A particularly poignant grid of color photographs chronicles the long-term effects of exposure to toxic metals atomized in the air and spread downwind from a nearby mill, still in use. Frazier describes the results of an ionic foot detox that she and her mother tried: “My water was lighter, slightly translucent with a large amount of brownish orange yeast debris, thin lymphatic mucus, and black chips of heavy metals floating on top … Areas cleansed: liver, gall bladder, kidneys, intestinal tract, and the lymphatic system … Mom’s water was pretty dark with thick lymphatic mucus, indicating a congested liver and shredded lettuce-like particles from her intestinal track.”

The Notion of Family gilds its often grim truths with the hope of resistance, as in Frazier’s portraits of her Grandma Ruby—with her battalion of dolls, a stoic countenance, and a matriarchal sense of duty—who raised six children by herself on a Goodwill manager’s salary. In one photograph, she stands in her kitchen, her arm resting on the back of a chair where her grandson sits, light from the adjacent window pouring through a scrim of curtain and ivy, her nightgown slipping from her shoulder, her home a picture of order and cleanliness. “Grandma Ruby’s interior design was a firewall that blocked external forces,” Frazier writes.

Grandma Ruby and J.C. in Her Kitchen, 2006.

U.S.S. Edgar Thomson Steel Works and Monongahela River, 2013.

People in Braddock depended on the prosperity of the steel mills. Grandma Ruby’s stepfather worked for his entire life in Andrew Carnegie’s steel mill, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, “tearing down and rebuilding furnaces, cleaning up spilt metal and slag”; he eventually collected a pension, though as Frazier reminds us with an image of Grandma Ruby wiping his behind as he leans out of a wheelchair, the labor wrecked his body. Dennis C. Dickerson, who contributed another essay to the book, writes: “As long as black men offered their bodies to the enormous physical rigors required of mill labor and their wives and children breathed the contaminated air filling Braddock skies, Edgar Thomson made it possible for laborers to buy homes, educate their youth, and plan for the future.”

Throughout the book, Frazier invokes the specter of iconic Depression-era images from the Farm Security Administration, such as Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” (1936); Frazier has openly wondered what Florence Owens Thompson, Lange’s subject, might’ve said had she been invited to collaborate in documenting her family’s plight. Self-determination rarely figures in the social documentary tradition, and in many ways Frazier’s work seeks to redress this omission. That she defines her photography as a “conceptual documentary” practice speaks to her continued faith in the camera as a vehicle for both social change and aesthetic possibility: beauty, in her work, does not preclude protest any more than education presumes awareness.

“One of my goals is to disrupt the privileged point of view that only educated and elite practitioners can create work about the poor or disenfranchised,” she tells the artist Dawoud Bey in their interview for the book. “My mother did not have to read Roland Barthes to understand death in a photograph.”

Momme, 2008.

1980s “Welcome to Historic Braddock” Signage and a Lightbulb, 2009.

Jane Harris’s writing has appeared in Art in America, Artforum, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, The Believer, and elsewhere.

All photographs © LaToya Frazier and courtesy of Aperture Publishing

Gobble-uns

A photograph published alongside “Little Orphant Annie” in an edition of poems ca. 1900.

There’s a new iteration of Annie opening this year, starring Quvenzhané Wallis as the plucky eponymous orphan. You’ve probably seen the 1982 movie; maybe you’ve caught one of the musical’s many revivals. And most everybody knows that the musical itself was adapted from a popular and long-running comic strip. But did you know that all those were based, in turn, on the 1885 poem “Little Orphant Annie?” Or that James Whitcomb Riley wrote the poem about a real-life orphan, Allie? And that it’s creepy and scary? Well, now you do!

Mary Alice “Allie” Smith was an Indiana neighbor of the Riley family. When her father was killed in the Civil War, twelve-year-old Allie—the name change was a typographical error—came to live with the Rileys; the future poet was a child himself. Allie apparently entertained the other children of an evening with scary stories that made a huge impression on young James. The poem, which is made up of Allie’s cautionary stories, was one of his most popular, and a major part of his well-attended speaking tours. Well, it was the Victorian era.

Little Orphant Annie

Little Orphant Annie’s come to our house to stay,

An’ wash the cups an’ saucers up, an’ brush the crumbs away,

An’ shoo the chickens off the porch, an’ dust the hearth, an’ sweep,

An’ make the fire, an’ bake the bread, an’ earn her board-an’-keep;

An’ all us other children, when the supper-things is done,

We set around the kitchen fire an’ has the mostest fun

A-list’nin’ to the witch-tales ‘at Annie tells about,

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

Wunst they wuz a little boy wouldn’t say his prayers,—

An’ when he went to bed at night, away up-stairs,

His Mammy heerd him holler, an’ his Daddy heerd him bawl,

An’ when they turn’t the kivvers down, he wuzn’t there at all!

An’ they seeked him in the rafter-room, an’ cubby-hole, an’ press,

An’ seeked him up the chimbly-flue, an’ ever’-wheres, I guess;

But all they ever found wuz thist his pants an’ roundabout:—

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

An’ one time a little girl ‘ud allus laugh an’ grin,

An’ make fun of ever’ one, an’ all her blood-an’-kin;

An’ wunst, when they was “company,” an’ ole folks wuz there,

She mocked ‘em an’ shocked ‘em, an’ said she didn’t care!

An’ thist as she kicked her heels, an’ turn’t to run an’ hide,

They wuz two great big Black Things a-standin’ by her side,

An’ they snatched her through the ceilin’ ‘fore she knowed what she’s about!

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

An’ little Orphant Annie says, when the blaze is blue,

An’ the lamp-wick sputters, an’ the wind goes woo-oo!

An’ you hear the crickets quit, an’ the moon is gray,

An’ the lightnin’-bugs in dew is all squenched away,—

You better mind yer parunts, an’ yer teachurs fond an’ dear,

An’ churish them ‘at loves you, an’ dry the orphant’s tear,

An’ he’p the pore an’ needy ones ‘at clusters all about,

Er the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

Incidentally, the poem was also the inspiration for Raggedy Ann; but that’s a story for another day.

Planned Obsolescence

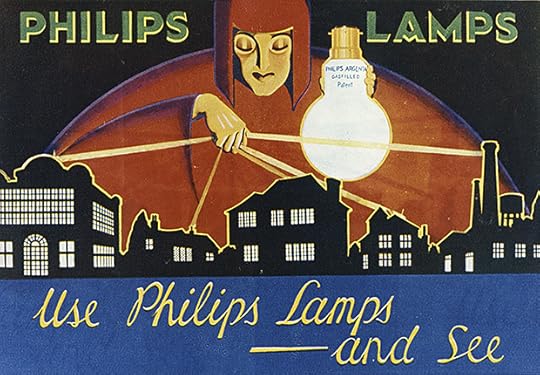

An ad from the Philips company archives.

Is Byron in for a rude awakening! There is already an organization, a human one, known as “Phoebus,” the international light-bulb cartel, headquartered in Switzerland. Run pretty much by International GE, Osram, and Associated Electrical Industries of Britain, which are in turn owned 100%, 29% and 46%, respectively, by the General Electric Company in America. Phoebus fixes the prices and determines the operational lives of all the bulbs in the world, from Brazil to Japan to Holland (although Philips in Holland is the mad dog of the cartel, apt at any time to cut loose and sow disaster throughout the great Combi-nation). Given this state of general repression, there seems no place for a newborn Baby Bulb to start but at the bottom.

But Phoebus doesn’t know yet that Byron is immortal …

—Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

I can remember reading Gravity’s Rainbow and marveling at the imagination on display in the famous “Byron the Bulb” section, in which a very chipper, eternally burning lightbulb (yes, that’s our Byron) finds himself in the crosshairs of Phoebus, a nefarious lightbulb cartel intent on controlling the life span of every bulb in the world.

At the time, I assumed without a second thought that Phoebus was a work of fiction—and why wouldn’t it be? The cartel was mentioned, after all, in basically the same breath as an all-girl opium den, “dildos rigged to pump floods of paregoric orgasm to the cap-illaries [sic] of the womb,” and, yes, a talking lightbulb.

Markus Krajewski, a media studies professor, was less skeptical: “I knew that Pynchon’s prose style mixes fact and fiction, and so I wondered: Could this be true?”

It was, his research revealed. Well, it kind of was—the Phoebus cartel really did exist, and it perpetrated what can only be called the “Great Lightbulb Conspiracy.” Appropriately enough, IEEE Spectrum—a trade magazine edited by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers—has Krajewki’s story:

On December 23, 1924, a group of leading international businessmen gathered in Geneva for a meeting that would alter the world for decades to come. Present were top representatives from all the major lightbulb manufacturers, including Germany’s Osram, the Netherlands’ Philips, France’s Compagnie des Lampes, and the United States’ General Electric. As revelers hung Christmas lights elsewhere in the city, the group founded the Phoebus cartel, a supervisory body that would carve up the worldwide incandescent lightbulb market, with each national and regional zone assigned its own manufacturers and production quotas. It was the first cartel in history to enjoy a truly global reach.

These companies colluded, it turns out, to engineer incandescent lightbulbs with dramatically attenuated life spans: over the next years, bulbs that once burned some fifteen hundred to two thousand hours were made to last for only a thousand, thus enabling every company in the world to sell more bulbs and artificially inflate prices. The ruse lasted until 1940, and it was surprisingly sophisticated in its execution; the companies involved made “very strenuous efforts … to emerge from a period of long life lamps,” as one executive wrote. I love the language there—as if efficiency was merely a phase, an independent variable, something to be waited out.

Read the rest of Krajewski’s piece here—and never again doubt the veracity of Pynchon.

Agatha Christie’s Diamond Cache, and Other News

Diamonds recovered from a compartment in a trunk owned by Agatha Christie.

Encouraging news for all who let their modifiers dangle: “A stickler insists that we never let a participle dangle, that you can’t say, ‘Turning the corner, a beautiful view awaited me’ … But if you look either at the history of great writing and language as it’s been used by its exemplary stylists, you find that they use dangling modifiers all the time. And if you look at the grammar of English you find that there is no rule that prohibits a dangling modifier … it was pretty much pulled out of thin air by one usage guide a century ago and copied into every one since.”

These are some ways we’ve received our mail: from pigeons, balloons, boule de moulins (“hollow zinc spheres the size of a man’s head and covered with fins … the idea was to place them in the river and let them float along the current … the service was canceled after just eleven days”), pneumatic rail, rockets, cats.

“Fincher appears to be more pessimistic about love than Kubrick was. Eyes Wide Shut, a post-Freudian work, takes sexual desire very seriously as a realm where the revelation of inner monsters makes it possible to live with them, with ourselves, and with each other. Gone Girl takes identity very seriously; it subordinates sex to power and love to pride, and suggests that the revelation of monstrosities brings knowledge without wisdom, adds pain to pain, covers masks with masks, and shows screens behind screens.”

When you’re stressed, you could drink and smoke or squeeze a rubber ball or get a spa treatment or indulge in some petty larceny—or you could just sit down and write a letter to yourself, which is apparently the way to do it.

An Agatha Christie fan has discovered the writer’s lost diamonds in a sealed metal strongbox bolted to the bottom of a trunk. “I had read Agatha Christie’s biography,” the fan said, “so I knew exactly what I was looking at.”

October 6, 2014

Once Everything Was Much Better Even the Future

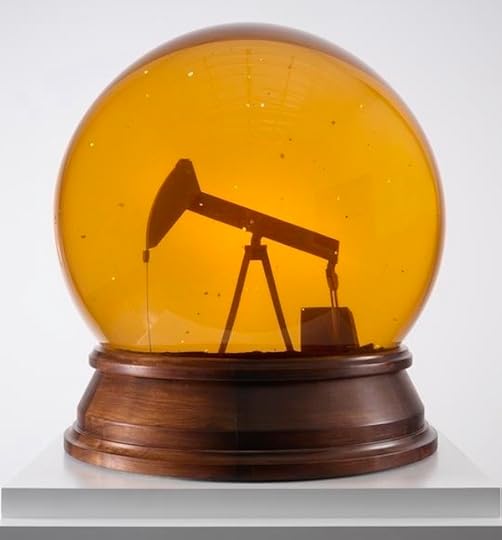

Nir Hod, Once Everything Was Much Better Even the Future, 2013, plexiglass, stainless steel, twenty-four-karat gold flakes, mineral oil, 78 1/2" x 42" x 42". Photo by Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Down the block from the Review is Paul Kasmin Gallery, where through October 25 you can see Nir Hod’s Once Everything Was Much Better Even the Future, which has the distinct honor of the most captivating snow globe I can recall having seen. (An honor formerly held by a particularly endearing Epcot souvenir from 1997—sorry, little guy.)

The globe is large—more than seventy-eight inches; the photo above doesn’t do justice to its scale—and it’s filled not with “snow” nor even “sno,” but with flakes of twenty-four-karat gold. Its vivid, lustrous amber color comes from mineral oil, and at its center is an ominous, gently swaying pumpjack. As the gallery notes, Hod’s work contains a “dark glamour that is both alluring and menacing”—this piece in particular brought to mind the iconic poster for Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood.

As Hod, who was born in Tel Aviv and lives in New York, told the Creators Project last month, “A generation ago, there seemed to be more collective romanticism, and I’m nostalgic for that.” That romanticism isn’t immediately in evidence here, but if you peer into the amber for long enough, you start to get a sense of it: the pumpjack, which begins as an emblem of rapacity, takes on a sentimental sheen without your even noticing.

“I’ve been told a number of times that people innately feel bad for the pumpjack because of the feeling of loneliness and despair imbued in it,” Hod said. I came away feeling faintly starry-eyed: how could such a beautiful machine do such violence to the landscape, et cetera, et cetera, the beauty of polluted sunsets, et cetera, are we all doomed, and so on. Then I stepped onto Twenty-seventh Street and was nearly hit by a cab, and the spell was broken.

Reunion

From a foreign edition of Reunion.

Glass half full: whatever the travails of the publishing industry, we live in a wonderful era for reissues. Think about it! All of Barbara Pym and Barbara Comyns are in print! Muriel Spark is having a moment! You want A Girl in Winter or Maiden Voyage or Sigrid Undset’s Jenny? You can have any of them within a week. Several of my new favorite books—In Love, Climates, After Claude—were introduced to me in recent editions. And people discuss Stoner and Speedboat as if they’re the latest must-reads.

Much of this is because of the hard work and great curation of publishers such as New York Review Classics, Persephone, Penguin, New Directions, and Lizzie Skurnick Books—to name only a few—but the readership is heartening, too. We want good books, but more than that, we want treasure. And the problem is, without library stacks and used bookstores, it’s increasingly difficult to stumble upon anything on our own. We depend on these publishers, and we depend on friends.

For all its chaos, the Internet does not make random book discovery as easy, I don’t think. Maybe that’s not a bad thing, altogether. I mean, I’ve read a lot of books, but I’m not what I would consider well read; there are too many gaps in my reading, it’s too scattershot, and too much of it has been bad. There were a lot of third-rate Victorian novels in the school library, or midseventies expository feminist novels from dollar carts, or memoirs by C-list celebrities. If I’d been shopping with intention—or, indeed, had had to pay shipping—I don’t think this would be as true. But for every random piece of pulp or strange book I’ve picked up on a stoop or at a thrift shop—okay, for every ten—there has been something worthwhile. I love the shelf of NYRB Classics in my local bookstore, but there’s less an element of discovery involved; you know what you buy will be worth reading.

I was talking online last night with some friends about what the next big new-old book would be; I joked that I had a hundred dollars on May Sarton. (I was only half joking.) I got several great recommendations out of the exchange, and I had the usual good feeling in the knowledge that there are tens of thousands of wonderful books we’ll never get to read, and thousands that could be potentially life changing, or at least life affirming.

It goes without saying that there are countless writers due for reappraisal and respectful reissue; just off the top of my head, what about Dorothy West, or Norman Douglas, or Helene Hanff? Elbowing the Seducer? Several of Rumer Godden’s adult novels—China Court, Greengage Summer—and her memoirs, are out of print in the U.S. (I’m willing to concede that there might not be a big market for Robert Farrar Capon’s Between Noon and Three: Romance, Law, and the Outrage of Grace, whatever my own feelings on the subject.)

I think if I had to agitate for one under-mentioned title, though, it would probably be Reunion, the 1971 novella by Fred Uhlman. Reunion is not exactly obscure—Arthur Koestler wrote the introduction to its 1977 reissue, and in 1989, Harold Pinter wrote the script for its film adaptation. Nor is it out of print; you can still buy the handsome 1997 FSG edition—though good luck finding it on the shelves of most bookstores. I first read it in college; it was loaned to me—an old hardcover copy—by my friend Dan. Later, I read it aloud to my family on a road trip. It is the story of the friendship of two boys in pre-war Germany. Here are the closing lines:

I don’t know where I read that “death undermines our confidence in life by showing that in the end everything is equally futile before the final darkness”. Yes, “futile” is the right word. Still I musn’t grumble: I have more friends than enemies and there are moments when I am almost glad to be alive. When I watch the sun set and moon rise, or see snow mountain tops.

I wonder if today people find the book too ingenuous, or too simple, or too old-fashioned. Maybe readers think they have read the story before. But I urge you to give it a try; it is short, and moving. I know that’s not the same as stumbling across it somewhere in the stacks—and those anonymous library bindings always give an added air of discovery!—but perhaps it can qualify as a treasure all the same.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers