The Paris Review's Blog, page 654

October 15, 2014

Wish You Were Here, and Other News

A still from a film recording of Eugen Weidmann’s execution, June 17, 1939.

Richard Flanagan has won this year’s Man Booker Prize for his novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North. “He instinctively hugged the Duchess of Cornwall as he received the award at a black tie dinner in London.”

Last night everything was peachy, but the Booker has a history of dust-ups and disorder. Also idiocy—Julian Barnes recalls an encounter after his novel Flaubert’s Parrot failed to win the prize: “I was introduced after the ceremony to one of the judges, who said to me: ‘I hadn’t even heard of this fellow Flaubert before I read your book. But afterwards I sent out for all his novels in paperback.’”

The guillotine at the dawn of the media age: in the Paris of 1939, the simplest way to stop executions was to film them. “Unbeknownst to Parisian prison officials, a film camera had been set up in one of the apartments overlooking the Place Louis-Barthou. The film recorded [an] execution and by the next morning photographic stills appeared on the cover of nearly every French newspaper … The public was scandalized by their own violence; the government embarrassed. In response France banned public executions.”

James Wood on the Australian novelist Elizabeth Harrower, whose work is back in print after twenty years: “[Harrower] essentially terminated her literary career. She has said that she thinks of her fiction as something abandoned long ago, buried in a cellar. She can’t now be bothered with writing. ‘I don’t know anybody who knows I’m a writer,’ she said in 2012.”

Against basic, the most modish putdown of 2014: “While what it pretends to criticize is unoriginality of thought and action, most of what basic actually seeks to dismiss is consumption patterns—what you watch, what you drink, what you wear, and what you buy—without dismissing consumption itself. The basic girl’s sin isn’t liking to shop, it’s cluelessly lusting after the wrong brands, the ones that announce themselves loudly and have shareholders they need to satisfy. (The right brands are much more expensive and subtle and, usually, privately owned.)”

October 14, 2014

The Literary Agent of Yore (Unspeakable Rascal!)

An illustration by Lauren Stout for Lawton Mackall's Bizarre, 1922.

My continuing odyssey across the World Wide Web—I’ll read it all, someday—has yielded these two gems from the public domain, both early constructions of the literary agent as a type; neither, I’m sorry to say, is very flattering.

Now as then, agents get a bad rap. In the popular imagination, they’re usually seen as unscrupulous middlemen, always on the phone, insistently plying their wares. The agent, we’re told, is a necessary evil at best, or, at worst, the first in a line of craven corporate interests designed to suck the marrow from a writer’s work, making it suitable for a wide and churlish readership. In movies, writers are always seeking agents, falling out with agents, or at the very least nervously talking to agents, twisting the phone line in their fingers. And then there’s the editor-agent relationship, in which the agent never wins: he’s either part of a profit-obsessed cabal keeping subversive “new voices” out of print, or he’s a tasteless entrepreneur disturbing the delicate rapport between editor and author.

I’d thought all this was a fairly recent phenomenon—I had always imagined it came from the eighties, when publishers couldn’t conglomerate fast enough and the soul was said to have fled the industry—but these two old books suggest it’s been going on much longer than that. Which makes sense: in publishing, the sky is always falling. Every year is an abysmal year for books and a terrific year for books. Editors no longer edit, except when they do; publishers care only for their bottom line, except when they don’t; the three-martini lunch is always dead, always quietly continuing. That’s what’s fascinating about these excerpts: they’re both about a century old, documenting that same thwarted intersection of art and capitalism.

First, from Arnold Bennett’s Books and Persons, an essay collection composed of work from 1908 to 1911, the parts cited below being from 1908:

The author will insist on employing an Unspeakable Rascal entitled a literary agent, and the poor innocent lamb of a publisher is fleeced to the naked skin by this scoundrel every time the two meet. Already I have heard that one publisher, hitherto accustomed to the services of twenty gardeners at his country house, has been obliged to reduce the horticultural staff to eighteen …

I am prepared to offer £50 for the name and address of a literary agent who is capable of getting the better of a publisher. I am widely acquainted with publishers and literary agents, and though I have often met publishers who have got the better of literary agents, I have never met a literary agent who has come out on top of a publisher. Such a literary agent is badly wanted. I have been looking for him for years. I know a number of authors who would join me in enriching that literary agent. The publishers are always talking about him. I seldom go into a publisher's office but that literary agent has just left (gorged with illicit gold). It irritates me that I cannot run across him. If I were a publisher, he would have been in prison ere now. Briefly, the manner in which certain prominent publishers, even clever ones, talk about literary agents is silly …

According to "a well-known member of the trade," the business is once again—the second time this year—about to crumble into ruins. This well-known member of the trade, who discreetly refrains from signing his name, writes to the Athenæum in answer to Mr. E.H. Cooper's letter about the disastrous influence of royal books on the publishing season. According to him, Mr. Cooper is all wrong. The end of profitable publishing is being brought about, not by their Majesties, but once more by the authors and their agents. It appears that too many books are published. Authors and their agents have evidently some miraculous method of forcing publishers to publish books which they do not want to publish. I am not a member of the trade, but I should have thought that few things could be easier than not to publish a book. Presumably the agent stands over the publisher with a contract in one hand and a revolver in the other, and, after a glance at the revolver, the publisher signs without glancing at the contract. Secondly, it appears, authors and their agents habitually compel the publisher to pay too much, so that he habitually publishes at a loss. (Novels, that is.) I should love to know how the trick is done, but “a well-known member of the trade” does not go into details.

And then, even more remarkably, “Lucy the Literary Agent,” from Lawton Mackall’s 1922 collection, the aptly named Bizarre:

“I know you will agree with me,” said Lucy, “that these stories by Perth Dewar are quite remarkable, quite the most distinctive things of the kind that have been done in years, and that your readers will like them immensely.”

Ethridge the Editor said nothing. It was unwise to contradict her; for of all the personal-touch literary agents, Lucy was the personal-touchiest. So he let her run on and on, trusting that eventually she would run down. Also she wasn’t bad looking—in her aggressive way.

“You’ve read them?” she queried suddenly.

“Why, certainly,” he lied, glancing with studied casualness at the Reader’s Report slip attached to the blue manuscript cover.

Ethridge never read anything he could possibly avoid reading. He was one of those successful editors who edit by belonging to the best clubs and attending the right teas. Mere perusal of manuscripts was not particularly in his line.

The Report slip said: “Costume stories of Holland in the 17th Century. Only moderately well done. Not suitable for this magazine.”

“Who is this Dewar person, anyhow?” asked Ethridge defensively.

“You mean to say you haven’t heard of him? Why, my dear Mr. Ethridge! Dewar is a man of independent means—lives on his estate down in Maryland and writes stories between fox hunts. Enormously gifted.”

She failed to add, however, that Dewar had offered to let her keep any money she received for the stories—provided she could get them printed.

Resting her white elbows on Ethridge’s desk and eyeing him with calculating coyness, Lucy knew that he had not read the stories. She would make him wonder if she knew he hadn’t.

“What do you yourself honestly think of them, Mr. Ethridge? Candidly, now. You’re always so delightfully frank with me, Mr. Ethridge. That’s why it’s such a pleasure to deal with you. How did they strike you?”

“Really, Miss Leech, I don’t see how in our magazine we could possibly—”

“Now, Mr. Ethridge!” She held up a reproving finger, laughing roguishly. “But what’s the use of our trying to discuss imaginative literature here in your busy office with the telephone ringing every moment—or threatening to ring—and your discouragingly pretty blonde secretary—the minx!—popping in continually to see if we’re behaving!”

Ethridge smiled complacently. Why be an ogre?

“I tell you what. Let’s have supper at my studio this evening,” continued Lucy. “It’ll be so much more satisfactory to discuss things sensibly, without interruption.”

So he did, and they did.

At breakfast it was finally decided that the series by Perth Dewar should consist of ten stories, including four still to be written.

Ethridge salved his conscience by resolving secretly that they should all be published in the back of the book.

In due course of time the first story appeared. It contained a mean reference to the Knights of Pythias, or Mormonism, or a former Vice-President of the United States, or something; for which reason the issue containing it was suppressed.

Whereupon the buried issue became a Living Issue. The intelligentsia rushed to the rescue with highbrow hue and cry. Round robins were circulated. Newspaper columnists got sarcastic. Liberal cliques chittered. Perth Dewar became suddenly significant.

The issue containing the second story was sold out the day it appeared.

By the time the third one was out, Professor Lion Whelps, of Yale, proved in an article in the Sunday Times, that Dewar’s attitude toward women was like Turgeniev’s, and Professor Brando Methuseleh, of Columbia, discovered he had cadences. Sinclair Lewis inserted a mention of him in the forty-ninth edition of “Babbitt”. Nine British novelists hurried over to lecture on him.

And Ethridge?

He was made. In acknowledgement of his peerless editorial acumen that could discern true genius at a glance, the directors of the magazine doubled his salary and gave him a bonus to keep him from being coaxed away by the “Saturday Evening Pictorial”.

And Lucy?

Ethridge married her to keep her quiet.

Wanna Be Like Everyone

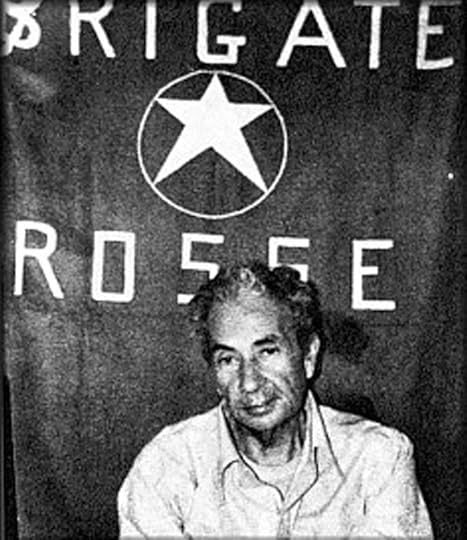

Italy in the Years of Lead.

Photo: southtyrolean, via Flickr

In the Italy I first knew, the Italy of the midseventies, political debate seemed to constitute the molten core of every dramatic conversation. My Italian was good and improving, but it never really got good enough to penetrate the mist of political verbiage. “Compagni, cioè, nella misura in cui” was the standard Italian catchphrase, mocking the loopy revolutionary discourse of the time: “Comrades, I mean, to the extent to which…” If the militant jargon was eye-glazing, the newspapers printed a language that can only be compared to the incense-clouded Latin of the Catholic Mass, a series of hieratic shibboleths that resembled Abstract Expressionist dance, the high holies and sacred mysteries of a Kabuki facade behind which deals were being cut.

But one aspect of the political debate became dazzlingly clear to me on a July afternoon in 1977 when my flatmate Angela burst into the small apartment we shared; she had the day’s newspaper and sat down to read it at the kitchen table. Angela was tall, with a crazed serpent’s nest of curly, hennaed red hair, intensely exorbital brown eyes, stunningly uneven buckteeth, and a dangerous temper. She dressed in the uniform of leftist Italian students: vest over peasant blouse, long embroidered skirt, Dr. Scholl’s clogs, oversize velvet purse riding at hip height.

As she read one article, something broke in her usually impetuous demeanor. “Oh, mamma mia, quanto mi dispiace,” she keened softly, expressing her sorrow. A NAP militant—Antonio Lo Muscio—had been shot and killed by police on a piazza in Rome, and two female comrades were shot and wounded. Angela was openly mourning the death of people who had killed policemen and hoped to overthrow the state. I was already afraid of her temper and her glare, but I was now aware that her political beliefs went to a place much more glamorous and romantic, and far scarier, than I had guessed.

That scary, romantic Italy is at the center of Francesco Piccolo’s remarkable novel Il desiderio di essere come tutti (The Desire to Be Like Everyone), published last year, which received this year’s prestigious Strega Prize. It’s a sincere personal account of two looming personalities: Enrico Berlinguer and Silvio Berlusconi, respectively the beloved leader of the Italian Communist Party in the seventies and early eighties and—well, Silvio Berlusconi needs no introduction. Francesco Piccolo is fifty years old, and he’s spent his life working between those two figures; he’s a screenwriter and author and the artistic director of Italy’s Sanremo Music Festival—as comfortable with populism as with pop culture. The book’s two parts, “The Pure Life—Berlinguer and Me” and “The Impure Life—Berlusconi and Me,” imply a simplistic portrayal of the past forty years of Italian life, but the novel isn’t as easy as that dichotomy might suggest; it’s a beautiful, subtle evocation of the life of a single person and a whole country.

That scary, romantic Italy is at the center of Francesco Piccolo’s remarkable novel Il desiderio di essere come tutti (The Desire to Be Like Everyone), published last year, which received this year’s prestigious Strega Prize. It’s a sincere personal account of two looming personalities: Enrico Berlinguer and Silvio Berlusconi, respectively the beloved leader of the Italian Communist Party in the seventies and early eighties and—well, Silvio Berlusconi needs no introduction. Francesco Piccolo is fifty years old, and he’s spent his life working between those two figures; he’s a screenwriter and author and the artistic director of Italy’s Sanremo Music Festival—as comfortable with populism as with pop culture. The book’s two parts, “The Pure Life—Berlinguer and Me” and “The Impure Life—Berlusconi and Me,” imply a simplistic portrayal of the past forty years of Italian life, but the novel isn’t as easy as that dichotomy might suggest; it’s a beautiful, subtle evocation of the life of a single person and a whole country.

Piccolo’s is one of a number of recent books exploring the Years of Lead, the tumultuous period in Italian life that stretched from roughly the late sixties to the early eighties. He stitches together a history from his experiences in those years, at the center of which is the 1978 kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, the former prime minister. Moro’s murder resides at the core of the Italian psyche in the way that the JFK assassination once did for us: this and many other books and movies are coming out in Italy at a distance roughly comparable to the lapse from Dallas 1963 to the making of Oliver Stone’s JFK and the publication of Don DeLillo’s Libra.

It can be hard for an American reader to follow some of the currents of solidarity, hatred, frustration, and dashed hopes in this very political book. Piccolo is a gifted explainer, but nothing explains his ultimate embrace of the calm and superficial—his willingness to accept “human beings we’d never even known existed,” as he refers to Berlusconi and his ilk—the way that an episode from his family life does. He finds that his father has a complete collection of every article he’s written, most of them political anathema to the elder Piccolo, and yet dear to him because of their author. Family, in the end, trumps philosophy; the dangerous creatures of the political depths cannot swim in the shallows of love.

* * *

“I was born on a day in early summer in 1973, at the age of nine,” the novel begins; its opening scene is set in the late afternoon, in the deserted park of the Reggia di Caserta, an enormous royal palace a few miles outside of Naples. A local kid offers to show the narrator—Francesco Piccolo keeps himself studiedly anonymous, in keeping perhaps with the rules of autofiction, where the narrator may or may not be factually accurate—and a friend a secret place in the park of the beautiful royal palace, an unguarded freezer where they’ll be able to steal all the ice cream they can carry. The other two kids, laden with stolen ice-cream sandwiches and Algida cornetti, climb over the wall, but the narrator stays behind, maneuvering to be left absolutely alone in this immense place of majestic beauty:

It seemed to me, for one hallucinatory instant, that all the walks and lawns were completely overrun by hundreds of thousands of people, millions of them, striding from the palace uphill toward the waterfall, and these were all the human beings that had ever set foot in the palace grounds from when they’d been built until this very afternoon. And I was there too, in their midst.

This visionary experience marks the moment in which the narrator becomes aware of the outside world. He bookends his childhood with two major events of the Italian 1970s: the cholera outbreak of 1973 and the terrible Irpinia earthquake of 1980. Cholera is a terrifying disease, a medieval one, and the fact that a modern city should have fallen victim to it says all that needs to be said about the failures of the Italian postwar political class. Piccolo describes the terror of being a child in a cholera outbreak:

Vibrio. That was the word. Before, there had been no such thing, I could have gone a lifetime without ever hearing it. The cholera vibrio … It takes root in the small intestine and destroys the entire epithelium. But that’s not the way it was explained to me … what I understood, or had been told, is that the way you could tell you had cholera was that at some point you felt a stabbing pain in your belly, just overpowering, and then you went to the bathroom and what came out was this white stuff. That’s right: white. And this white diarrhea started gushing out, and it never stopped, ten or even fifteen times a day. Until all you were expelling was water, and you couldn’t hold it in. And then, in the end, you died…

The narrator spends weeks waiting for that stab of pain, dreading it, having nightmares about it. And then one day, at a movie theater, it comes. He sits out the movie, thinking in his nine-year-old mind that every minute he doesn’t go to the bathroom is another minute left to live. When he finally gets home, he goes straight to the bathroom and: it isn’t white. Turns out, as she does every summer, the narrator’s mother has secretly administered a purgative, part of the generally medieval Neapolitan health regimen. And he hates her for it. Hates her for superficiality. For persisting in ordinary life in the midst of an overpowering disaster.

Aldo Moro after having been kidnapped by the Red Brigades.

As he gets older, our narrator falls in with a radical crowd, though he’s careful to explain that the turning point was a soccer victory by the East German team; like many of the time, he’s in the thrall of Enrico Berlinguer, who from 1972 until his death was head of the Italian Communist Party—a Christ-like Communist leader who embodies decency, human respect, a lack of superficiality. The narrator even pines for one of his communist classmates, Elena, his equivalent of Angela. But when Moro is kidnapped by the Red Brigades, he begins to question his orthodoxy:

I saw, as I walked out the front gate and went practically running the length of the school’s green metal fence, that Elena and the others were hugging. You couldn’t say they were happy, considering that terror was unmistakably painted on their faces too, but they knew, and conveyed to each other—this was the meaning of those hugs—that they weren’t sorry that the Red Brigades had kidnapped Moro. I stopped to watch them for a moment … I watched them, I envied them; and at the same time, my stomach ached with nausea.

Later, after the Irpinia earthquake, his conscience clouds even further, as the superficiality he once witnessed in his mother takes a political form; in the eighties, the moral stature of the Italian Communist Party made way for the profiteering hustle of the Italian Socialist Party and its slick leader, Bettino Craxi. In his Milan mansion, Craxi, to give you some idea, kept a pet lion that had been given to him by a Mafia hit man. It’s hard to overemphasize the corruption that pervaded the Italy of the eighties—and Craxi was a close ally of, yes, Silvio Berlusconi, the best man at his wedding, a loyal guardian of Berlusconi’s political interests. Craxi finally fled Italy, dying of cancer in exile, a fugitive from the law on a resort island in Algeria like a latter day Pompey the Great. With Craxi gone, Berlusconi went looking for a replacement. He decided the best candidate was himself.

So the crucial thing to understand is that Craxi and Berlusconi are largely a single entity, operating in lockstep in Italy’s political history. One of the cruelest and most buffoonish moments of that history came in 1984, when Enrico Berlinguer was invited to speak at the Socialist party congress. It’s a tradition, this invitation of the colleague-rival to come and address the party rank and file, but this congress was different. This was a party of profiteers and connivers, a party that sensed its opportunity was at hand—a party that scorned Berlinguer’s old-fashioned attachment to the good of the people, the principles of social justice, the idea of economic equality. The narrator describes how Berlinguer made his way into the sports arena where the congress was being held, how a chorus of “sce-e-e-emo,” or “i-i-id-i-i-o-ot,” echoed overhead, accompanied by a shrill symphony of derisive whistles, the most profound insult an Italian crowd can offer, the equivalent of the shoes waved overhead during the Arab Spring. And how Craxi, the next day, addressed his followers, now slightly abashed but still defiant, and declared, “I didn’t whistle. But that’s only because I don’t know how to.”

Communists signing the front page of l'Unità at Berlinguer's funeral.

Less than a month later, a broken Berlinguer collapsed while addressing a public assembly and died, a month to the day after being whistled into silence. His funeral in Rome was a momentous occasion—two million people gathered, and the communist newspaper, L’Unità, ran a banner headline: TUTTI. “Everyone.” But when this moment comes in Il desiderio, the narrator stays home, alone, afraid to become part of “everyone,” certain that he’s not really the communist he pretends to be. He was, after all, a communist who would later become a successful novelist and screenwriter, a communist with plenty of money, a communist who is actually published by a publishing company owned by Berlusconi. And a communist who, like all Italians of his generation, lived through something very close to a civil war. Still, as the coffin moves through the throng on the tiny television he watches, he bows his head, tears streaming, and holds his right fist high in solidarity.

That opening scene at the Reggia di Caserta—the narrator’s intellectual awakening—pairs neatly with the start of the second part of the book, when the narrator, now thirty and a longtime member of the Italian Communist Party, describes the advent of Silvio Berlusconi, at a 1994 G7 meeting held, of all places, at the Reggia di Caserta.

Berlusconi spent a long time admiring the fountain … I can’t say that the people who were with him were his friends, but he too was inside the Reggia which was closed to the public, and he hadn’t even had to climb over a wall. It was already dark, but for the first time the entire park had been illuminated at night—and it was empty.

Listening to the splashing water and looking down at the lit-up, empty grounds, Berlusconi announces to his fellow statesmen that this is a very romantic place. “Look out,” he says, “or tonight we’ll be increasing the population.”

Berlusconi at the Reggia di Caserta with Bill Clinton, in 1994.

To the narrator, seeing Berlusconi

there, in that exact spot—where I belonged—and hearing him utter a lascivious and awkward phrase—and especially to older people, in all likelihood too old now ever to have children again—[…] such an unseemly phrase, dripping with a demented, ruinous libido, tantamount to a broad and knowing wink of the eye, at the level of jokes out of weekly puzzle magazines—gave me an exact perception of the time that had passed; it gave me an exact perception of what had come with Berlusconi’s election.

He describes the wave of despair that had come over his fellow Italian Communists as they watched the election results: “We would all have to go live in another country, more civilized, more in tune with us, because Italy had fallen into the hands of human beings we’d never even known existed.”

The second half of the book is an intelligent meditation on living in—and through—twenty years of Berlusconi, but it also contains a deeper and wiser exploration of the importance of superficiality: Better Living through Shallowness. True political depth requires hatred, or the ability to hate, but think of Piccolo’s father, still collecting clippings of his son’s radical articles. Or think of Piccolo himself, in his capacity as artistic director for the Sanremo Music Festival. What could be more vacuous, more politically empty, than a national pop-music extravaganza? And yet Sanremo brought much of the sound track to the radical, troubled, happy-sad Years of Lead.

Throughout the book, a chorus of fellow communists says it’s time to leave Italy, that it’s impossible to live in an Italy run by Berlusconi. But what if you love Italy? What if you love the Italians, in all their relentless maddening idiosyncrasy? And this is how Piccolo ends: “Those who say they want to leave this country, or simply spend their whole lives saying they want to leave, do so because they want to save themselves. Well, I’m staying here. Because I don’t want to be saved.”

The last time I saw Angela was on a blustery fall day in Perugia. I had finished my course in Italian and was heading back to college in California at UCLA, which I still mentally pronounce ooklah, in the Italian style. She was in a blind panic, rushing to the hospital where her boyfriend Michele, the third occupant of our apartment, was struggling for life after his third or perhaps fourth overdose. This was where a great deal of the energy of that generation finally dissipated, and every left-wing screed you read from those years theorizes an unholy alliance between a conservative government and the Mafia. There was so much death in those years, so much misery and so much loss. If the shallows of love and family are what Italy finally comes up with to salve those wounds, if the Sanremo song festival can provide some balm, who can call that wrong?

Antony Shugaar is a writer and a translator from the Italian and the French. He is a contributing editor to Asymptote Journal. Among his recent translations are Walter Siti’s Resistance Is Futile (which won the Strega Prize in 2013), Viola Di Grado’s Hollow Heart, and the Nobel laureate Dario Fo’s The Pope’s Daughter. He has published articles in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, and The New York Review of Books.

Ultrarumpus

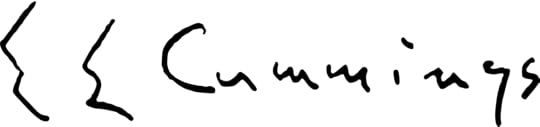

For E. E. Cummings’s birthday: a letter he wrote to Ezra Pound in October 1941, larded with gossip, political commentary, neologisms, and mordant pseudonyms. (Look out for Archibald MacLeish and William Carlos Williams, among others.) Pound and Cummings first met in Paris in 1921; this letter and others from the expansive Pound-Cummings correspondence appeared in our Fall 1966 issue, with Cummings’s “often eccentric punctuation and his verbal byplay intact.”

October 8, 1941

DEAR EZRA—

whole, round, and heartiest greetings from the princess & me to our favorite Ikey-Kikey, Wandering Jew, Quo Vadis,Oppressed Minority Of one, Misunderstood Master, Mister Lonelyheart, and Man Without A Country

re whose latest queeries

East Maxman has gone off on a c-nd-m in a pamphlet arguing everybody should support Wussia, for the nonce. “Time” (a loose) mag says Don Josh Bathos of London England told P.E.N. innulluxuls that for the nonce writers shouldn’t be writing. Each collective choisi(pastparticiple,you recall,of choisir)without exception and—may I add—very naturally desires for the nonce nothing but Adolph’s Absolute Annihilation, Coûte Que Coûte (SIC). A man who once became worshipped of one thousand million pibbul by not falling into the ocean while simultaneously peeping through a periscope and sucking drugstore sandwiches is excoriated for,for the nonce,freedom of speech. Perfectly versus the macarchibald maclapdog macleash—one(1)poet,John Peale Bishop, hold a nonce of a USGov’t job;vide ye newe Rockyfeller-sponsored ultrarumpus to boost SA infrarelations. Paragraph and your excoed Billy The Medico made a far from noncelike W.C. of himself(per a puddle of a periodical called “Decision”)relating how his poor pal E.P. = talented etc but ignorant ass who etc can’t play the etc piano etc… over which tour d’argent the wily Scotch duckfuggur Peter Munro Jack 5 Charles Street NYCity waxed so wroth he hurled at me into New Hampshire a nutn if not incandescing wire beginning “stab a man in the back but do it three years too late”:’twould hence appear you’ve still some friends, uncle Ezra, whether vi piace or non

now to descend to the surface;or, concerning oldfashioned i: every whatsoever bully(e.g. all honourless & lazy punks twerps thugs slobs politicos parlourpimps murderers and other reformers continues impressing me as a trifle more isn’t than least can less and the later it’s Itler the sooner hit’s Ess. Tune: The Gutters Of Chicago

“make haste” spake the Lord of New Dealings

“neutrality’s hard on my feelings”

—they returned from the bank

with the furter in frank:

& the walls,& the floors,&the ceilings)

As my father wrote me when I disgraced Orne—forsan et haec. And the censor let those six words through

hardy is as hardy does

—salut!

Trim Size

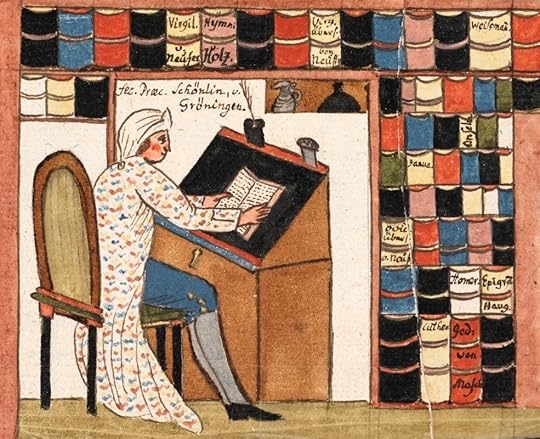

An illustration from Bundesbuch von Magenau (Book of the Covenant of Magenau), 1790.

One of the many things that dates my childhood firmly to the eighties and early nineties is the ubiquity of large reference books in it. Reference books, big ones, figure in most of my memories; I guess they were easy to find at tag sales. At any given moment, you could find me poring over The Great TV Sitcom Book, The Doctor’s Book of Home Remedies, Best Movie Quotes, or The Big Broadway Fake Book, which is in fact probably still in use for auditions, since it contains only sheet music. (I read this only in moments of desperation.) However, it should be said that lines were drawn: someone once gave my family one of those dedicated Great American Bathroom Books, and my mother found it disgusting and threw it away immediately.

For a few years, this sort of tome—eighties excess between two covers—must have had imprints in every major publishing house of the era. There was a distinctive look to the volumes, which were probably intended as gifts or coffee-table items, but had their own low shelf at our house. Monumental title adjectives—great, big, ultimate, definitive—were desirable. The font had to be assertive. It was also a good idea to have lots of the content listed on the jacket, a taste of the great knowledge contained therein. Obviously they had to be physically large, as unwieldy as possible—although I carried them from room to room. It wasn’t just me, either. My friends liked them, too, as I remember, but this may be a comment on the quality of entertainment on offer at my playdates.

Genrewise, I was particularly fond of esoterica, such as the sort found in The People’s Almanac. That and a huge volume of obscure baseball trivia were both in heavy rotation, although I don’t recall ever particularly impressing anyone with my knowledge. The finest book of all was one I found at my grandparents’ house: it was called The Best, and it authoritatively identified all the best stuff in the world. I guess it was the end of an era of absolutes; the 1981 Genius Edition of Trivial Pursuit was a mark of your knowledge, the Scrabble Dictionary had the last word, and if some guy said that the Bentley Fortissimo was the greatest tennis racquet of 1984, well then, that was that.

Some of the big books served a specific function, of course. My brother had enormous compendia of Simpsons trivia, and we had one devoted to the history of the Little Rascals. In a pinch, I would curl up with a Leonard Maltin omnibus; I also had a book called the Film Encyclopedia that I read, for fun.

I went into this feeling very nostalgic, thinking of a time when you got your trivia from between two covers, rather than a digital rabbit hole. And it’s certainly true the Internet has rendered this genre—or whatever it was—obsolete. Yet, walk into any Urban Outfitters: stupid books are enjoying a golden age. On one book cover, a dog balances a slice of watermelon on its nose. A furious cat glowers from another. A third promises hundreds of pages worth of drinking games. Yes, they may be smaller and more portable. But there are memories to be made there.

Thinking Hurts, and Other News

George Cruikshank, The Head Ache, 1818.

Flannery O’Connor on a 1957 television adaptation of her story “The Life You Save May Be Your Own”: “Well, I have seen the production and I thought it was slop of the third water. I aver that everybody connected in any way with it, except me, had a stinking pole cat for a mother and father.”

Thomas Pynchon doesn’t enjoy talking to reporters, but he’s not really a recluse—who saddled him with that reputation? It may have been none other than our own founding editor: “It all started fifty-one years ago, in 1963, when George Plimpton in the New York Times published the line: ‘Pynchon is in his early twenties; he writes in Mexico City—a recluse.’ It is doubtful if Plimpton, who helped create The Paris Review, knew at the time that he was accidentally kicking off the largest and longest game of Where’s Waldo? ever conceived. Nevertheless, the label has stuck.”

Daily bummer: “We must reckon with the fact that pop culture really likes to be agreeable along with its thrills. It likes to say yes, and makes endless conciliations to do so. It is safer to say yes. Yes can be deeply pleasurable. History is made by those who say no.”

Kierkegaard’s prescience extends to cyberbullying and trolls: “If, for instance, I enter a place where many are gathered, it often happens that one or another right away takes up arms against me by beginning to laugh; presumably he feels that he is being a tool of public opinion. But lo and behold, if I then make a casual remark to him, that same person becomes infinitely pliable and obliging … That is what comes of living in a petty community.”

Is contemplation a pleasant exercise? No, experts say, “most people would rather give themselves an electric shock than be alone with their thoughts.” But “proclaiming that we’re unable to enjoy our own thoughts suggests that our mental weather is always supposed to be pleasant … The human mind is not meant to resemble a postcard from paradise forever fixed in a state of tropical bliss. It’s a vast and perplexing wonderland whose entire topography can change in an instant.

October 13, 2014

Carolyn Kizer, 1924–2014

I’ve been enormously fortunate. People say, How do you feel about your reputation? My real belief is that I have exactly the reputation I deserve … on the whole I feel comfortable with myself. You know I’ve always always loved that line from Chaucer’s Criseyde, “I am meyne own woman wel at ease.” That’s the way I feel. Of course, there are always disasters looming, both cosmic and domestic. But even if it should all end tomorrow I would just hope I’ve burned enough bad drafts and old love letters!

—Carolyn Kizer, the Art of Poetry No. 81, Spring 2000

Carolyn Kizer died last Thursday at eighty-nine, the New York Times reports. Her poems are immaculately crafted and very smart, often with a steely feminism; she won the Pulitzer Prize in 1985 for her collection Yin. As the Times says, “She was writing as early as the 1950s about the conflict for women between the creative imperative and social expectations—but it was far different in character from that of her contemporary Adrienne Rich. Where the poems of Ms. Rich, who died in 2012, landed like bombs flung from the barricades, those of Ms. Kizer felt more like a stiletto slipped between the ribs.”

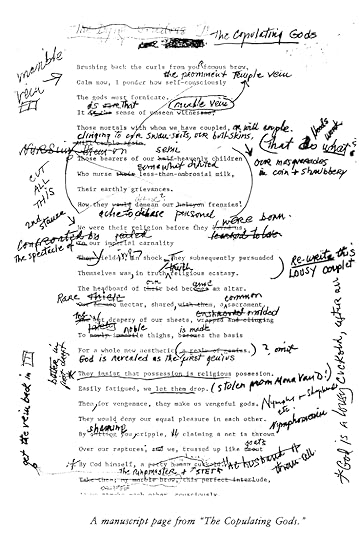

Ursula K. Le Guin called Kizer’s poetry “intensely, splendidly oral, wanting to be read aloud, best of all to be read or roared by the lion herself.” Kizer, born in Washington, was known for her long, careful periods of revision, as evidenced in the manuscript above. (She was an honest self-critic, too; note that “Re-write this LOUSY couplet” scrawled in the margin.) She took more than thirty years to edit the sequence “Pro Femina,” which contains one of her most famous lines: “We are the custodians of the world’s best-kept secret: Merely the private lives of one-half of humanity.”

In addition to her Writers at Work interview, The Paris Review published many of Kizer’s poems, including “Twelve O’Clock,” in our Winter 1990 issue; and “Gerda,” which opens with an old Swedish children’s prayer, from Spring 1987. To celebrate her life, we’ve made them both available online.

From “Twelve O’Clock”:

At seventeen I’ve come to read a poem

At Princeton. Now my young hosts inquire

If I would like to meet Professor Einstein.

But I’m too conscious I have nothing to say

To interest him, the genius fled from Germany just in

time.

“Just tell me where I can look at him,” I reply.

From “Gerda”:

Down the long curving walk you trudge to the street,

Stoop-shouldered in defeat, a cardboard suitcase

In each hand. Gerda, don’t leave! the child cries

From the porch, waving and weeping; her stony mother

Speaks again of the raise in salary

Denied. Gerda demands ten dollars more

Than the twenty-five a month she has been paid

To sew, cook, keep house, dress and undress the child,

Bathe the child with the rough scaly hands

she cleans in Clorox; sing to the child

In Swedish, teach her to pray, to count her toes

In Swedish. Forty years on, the child still knows how.

Royal Quiet Deluxe

Marinus Adrianus Koekkoek, In the Chicken Yard, ca. 1850, oil on canvas, 22.8" × 29.7".

In 1972, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings changed the face of country music forever with the Outlaw country sound. In 1974, the Ramones did the same thing for rock ’n’ roll. In 2000, my friend Tim and I set out to do the same for both genres with a way-out sound and a more ambitious instrumentation.

We call ourselves Royal Quiet Deluxe, which is also the make and model of the typewriter I play as percussion. Tim plays the guitar and the bass, often simultaneously. We provide the backing rhythms for two live chickens that peck out abstract melodies on toy pianos.

Every rehearsal and performance is a spontaneous improvisation, and no two performances are ever the same. The chickens are named Kitty Wells and Patsy Cline. Different individual chickens come and go, but in our pretentious barnyard Menudo they are always named Kitty Wells or Patsy Cline.

The band played two shows last year in college that we felt went incredibly well. Our former housemate lives in Japan now with a boyfriend who books bands in Osaka and Tokyo. We lied to her a little about how much we’d improved since graduation, and she lied to her boyfriend a little more on top of that, and now he says that if we can get him a solid live tape, of an actual show with a cheering audience and everything, he can book us a tour in Japan.

And you just know Japanese people are crazy about this kind of shit.

So now we’ve got to get a gig together, which you would figure would be hardly any problem at all, given the solidity of the whole general concept. But it’s harder than you might think, mainly because we are in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy. On the one hand, Richmond has a rich history of highly weird independent music—hardcore legend Avail is from Richmond, and it doesn’t get louder and weirder than GWAR, from right here in the 804. But then again, it’s like this town is doing the same thing with punk rock that it’s doing with the Civil War, just running reenactments until the old ghosts rise again.

Here’s the other thing on top of all that: you can’t have a show unless you can sell booze. And you can’t get a liquor license in this town unless you sell food. Then the city has this bullshit ordinance that says barnyard animals are not allowed into restaurants, even if they’re caged the entire time. It’s totally fine to chop them up, deep-fry ’em, and serve them with a side of collard greens, but if they want to come in through the front door and contribute to the rich tapestry of American music, that’s not allowed.

It’s this kind of attitude that’s holding the South back.

Tim and I live in a sagging two-bedroom apartment in the center of a block bedazzled with dried dog turds, half a mile from a stately row of monuments to Confederate war heroes flanked by a statelier stretch of historic homes. When you have chickens in your band, you do what the chickens do, which means waking up at dawn and rehearsing for a while before heading off to a beige job full of gray people reading a script into a telephone, and then coming back again to practice at dusk before the birds bed down for the night. We get an extra few practices on the weekends, but it really cuts into our social lives.

Some Sundays we sit there and listen to Johnny Cash for a while and then feel the fire so hard that we get up and try to capture it for ourselves. I figure out how to mic that typewriter up just right and I can get a really nice, booming, kick-drum sound from the shift and space-bar keys, and the letters thwacking on the cylinder make for a sharp snare sound. It’s pretty easy to reproduce Fluke Holland’s driving, minimalist drum sound on a typewriter if you’re really paying attention.

So I get a nice rhythm going on that typewriter and Tim smokes out that signature “Folsom Prison” riff and then the birds kick in all over the place, improvising and freestyling. Sometimes we get to going on that for twenty minutes or so, and a hole opens up in the fabric of everything and we slip through it into a palace of pure white light.

Right in the middle of it all, the father of one of my best friends calls me up. He’s the president of the local university and he says that the Reverend Al Sharpton is coming to speak at his school and would I like to not only come to the speech but eat dinner right next to Sharpton beforehand.

I strongly believe that you’ve got to take every opening you can get, even if you don’t understand it at all.

I’m seated at a large circular table across from my friend’s father and right next to Reverend Al Sharpton. Everyone else at the table is an exceptionally successful and prominent member of the African American community in southeast Virginia. There are CEOs and military brass and ministers and revered professors, as well as the coach of Hampton University’s basketball team. My friend’s dad says, Well, Reverend Sharpton, we all know what you do, but maybe we could go around the table and introduce ourselves and say what it is that we do for a living, starting with the young man to your right.

Would I ever! I say, Well, I temp to make money, but really what I’m into as a passion is that I play the typewriter as percussion in a country-rock band featuring two chickens that play toy pianos. Sharpton’s eyes widen to maximum strength, and then his pupils dash upward and back in an eye-roll so hard it probably sprains his optic nerves.

Hampton University’s basketball coach is seated on the other side of Reverend Al, and he leans over with an intense and gleeful intrigue, saying, Chickens! Really! Tell me more!

Well, I say, what we do is we glue corn to certain keys on the keyboard that are in tune with what the guitar is playing, and we practice at feeding time. We throw a bunch of corn on the keyboard so they can get a meal, which also makes them kind of a free-jazz Sun Ra thing all over the place at first, but they eventually lock into a more repetitive groove that’s in tune once they eat up all the loose stuff.

It feels so good to have an audience, even if we aren’t actually technically playing. I go all the way into how I see us fitting into and stretching the boundaries of country and rock music, and I don’t even really know what all I am saying. I just keep going. I have a dissociative moment where I’m hovering above my own body, watching Al Sharpton be like, God, Jesus, please make this boy stop, as a plume of pure purple bullshit hoses out of my mouth and all over the table. I see everyone else nodding politely and checking their watches, stifling yawns. But the me that’s still talking about the band is still talking about the band.

Al Sharpton’s speech makes me want to get out in the streets and get active, to get myself organized and help my community to do the same. I approach him afterward to tell him how much he’s inspired me and shake his hand. But he sees me coming—he meets my eyes, rolls his eyes again, turns his back, and vanishes behind his security.

Al Sharpton hates our band, man, I tell Tim the next morning. Tim takes a long drag on last night’s roach, exhaling slowly through his nostrils and says, I don’t believe we started this band just to impress Al Sharpton. We’re about a lot more than that. Now let’s take “Folsom Prison” from the top.

* * *

Sharpton’s disapproval bothers me even more than I want to admit out loud. I’m beginning to think that the whole band is little more than a concept that’s going to burn up like a meteorite as it falls into reality’s atmosphere. Having a prominent, widely respected figure who obviously has his whole life together think that the concept—arguably, the best part about the band—is dumb, too: it unties the dinghy of my self confidence and shoves it away from the pier.

Then the unthinkable happens: a band of Sun Ra devotees asks us to open for them at a show in an art gallery. There’s no health code to violate, but the show is coming up really fast. We call everybody, get a bunch of flyers made and out at all the record shops. Ticket sales are doing well. But sometimes when you get what you think you want, it feels like the universe is actually calling you on your bullshit bluff.

We may not actually be all that good.

One morning I snap a little: Tim, we have a show in two week’s time and we’re going to get up in front of everyone we know with these chickens and look ridiculous. But the birds, man, the birds can only practice until they’re full at breakfast and dinner. How are we going to get more practice time?

He thinks for a second. Then he scoops up a bird, engulfing its head inside his armpit, and says, Hey now, check this out. It thrashes a little and then settles into deep, steady breaths. You have never heard a stranger sound than that of a chicken’s snores muffled by a man’s armpit.

I learned this on the farm as a kid, he says, All you have to do is plunge a chicken into darkness for a few minutes and it goes right to sleep. It’s like pressing Ctrl-Alt-Delete on their little brains. It just reboots the whole system. And it’s a whole new day with a whole new breakfast.

He pulls the chicken out into the light. It opens its eyes and squawks, flapping back down to the keyboard to peck at the corn again.

With this we’re able to stretch a twenty-minute rehearsal to forty or fifty minutes, plunging the birds into our underarms when they slow up on the keys. Eventually they hit a wall and become sluggish. It’s like making pâté in slow motion. Whether or not our music improves, we do gain confidence, which is arguably more important.

It’s the night of the show, and the four-track we’re going to use to launch our Japanese art-rock careers is acting a little wonky. It will only record if it’s at a forty-five-degree angle. We duct-tape it to a shoe and hope for the best. The place is packed; even some of the GWAR guys are there. We’ve wrapped the birds’ cage in a large American flag, and I whip it off with a flourish to reveal Kitty Wells, Patsy Cline, and their keyboards. The stage lights hit them and they wake up, and Tim and I lay down what we know to lay down with maximum efficiency, allowing the birds to figure out their surroundings and come into the song with a bang.

The crowd erupts and for a moment we are all floating in the white light together, the birds and the band and the crowd. Then Kitty Wells pecks Patsy Cline right in the eye, opening up a blood spurt right across the tiny, white ivories on her toy piano. Someone in the crowd goes Ooooo and they all jump to their feet, edging closer to watch a spontaneous cockfight. We each grab a bird and stick its head under our left armpit while taking a deep bow. And that’s pretty much the end of it.

We check the tape the next night, and the recording messed up. The duct tape that was supposed to hold the shoe in place peeled off a layer of dirt instead, and the four-track settled at a bad angle. It’s a bummer, but after a performance like that, we shouldn’t have much trouble getting another gig, and we’ll make sure and tape that four-track to a clean shoe next time.

But I’m calling around looking for shows, and one of the guys from GWAR puts it to me straight, sort of: Listen, that show was a lot of fun, but you guys are not exactly headlining material. But nobody wants to go on after you, either.

The dejection seeps down into our bones. We take Kitty Wells and Patsy Cline back to a bemused farmer outside of town, and then the band breaks up. Tim moves to San Francisco, goes to grad school for art, and starts growing weapons-grade marijuana. And eventually I move to New York with no more sense of direction than I had when we started this band in college.

That’s where the story should end. Or it’s where the story really should have ended, if I could just let the past be the past. But late one night about ten years after Royal Quiet Deluxe’s tragic dissolution, I’m in a comic-book shop in Union Square and I see the Reverend Al Sharpton browsing the stacks. It’s surreal to find him here, a controversial civil-rights icon flipping through the latest Batman releases, and I just want to make a connection, to see if he remembers me and the band from that dinner a decade ago. To live on in the mind of someone that really matters, that’s a form of accomplishment itself. And it’s the only accomplishment Royal Quiet Deluxe has left.

I trail him, keeping my distance until he’s not near anyone else; then I sidle up to him and say, Reverend Sharpton? Is that you?

He looks at me, stunned, his eyes wide. I clarify: We had dinner together in Virginia about ten years ago, do you remember? I played the typewriter in that band with chickens that play toy pianos, and you gave an exceptionally moving speech after dinner, and I’ve wanted to shake your hand ever since.

He snaps out of his silence, his mouth working, then roars, Motherfucker, you think I look like Al Sharpton? He’s not Al Sharpton at all, I see now, just a heavyset guy with slicked back silver hair, a thick but neatly trimmed moustache, and a stylish velour tracksuit draped in gold chains. He yells, What the fuck? and my face ignites with shame. I drop my comics on the floor and bolt out into the night.

I know now, in 2014, what I wish I knew then: that closure is a story we tell ourselves, a momentary seizure of the ego, an attempt to reach back in time and rearrange events so that we look cool to ourselves and our self-image can carry on intact. When you have a strange vision you’re trying to turn real, loneliness and misunderstanding are just part of the process. If you’ve got a strange portal to something massive and wonderful, you’ve just got to yank that thing open on the regular any old way you can. You don’t need the real Al Sharpton or some phony Al Sharpton to approve of it, either.

People will not get you at first, but eventually they will—and they’ll act like they discovered you themselves or knew about you all along. Soon the whole world will warm their hands by your weird flame.

Listen to a recording of Royal Quiet Deluxe above.

Jeff Simmermon is a writer, storyteller, and stand-up comedian in Brooklyn. He has appeared on This American Life and won The Moth’s New York SLAM with a version of this story. He produces and performs in “And I Am Not Lying,” a show featuring stand-up, storytelling, and burlesque, at UCB East. Follow him on Twitter @jeffsimmermon.

No One Can Draw Runners, and Other News

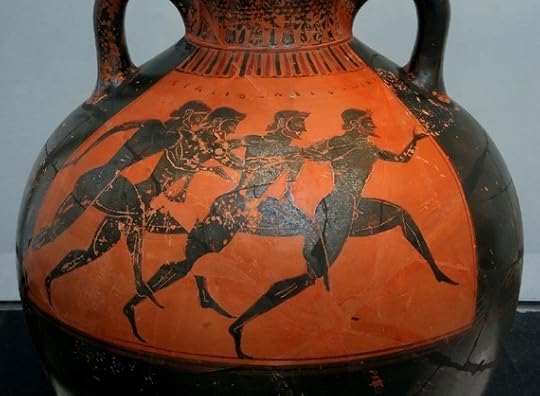

A Greek vase with runners at the panathenaic games, ca. 530 BC.

“Picture a person running. You’re probably picturing [it] wrong. It’s okay, you wouldn’t be alone. It turns out that artists have been drawing people running incorrectly for thousands of years. From Greek vases to drawing handbooks to modern sculptures, even our very best artists can’t seem to get the pose right.”

A new anthology’s narrow definition of art: “There is certainly great value in drawing attention to the historical context of a poem. We ignore an essential feature of literature when we lose sight of its power as an artifact of a particular moment, place or era. Still, it is difficult to read Poetry of Witness without quickly sensing that the editors are gaming the system to support their narrow preconception of poetry’s utility.”

Censorship in China: great for sales. “Having a book banned in China is often a marketing coup for publishers selling copies abroad. In the age of social media, this dynamic appears to be playing out on the mainland as well … ‘Smothering someone is as good as crowning that person … A ‘smothering’ order is a reading list.’”

The art of brand names: ? (Pro tip: do not name your company Shpoonkle. It will fail.)

Against brunch: “There’s something more malevolent at work than simply the proliferation of Hollandaise sauce that I suspect comes from a packet. Brunch has become the most visible symptom of a demographic shift that has taken place in our neighborhood and others like it … Our once diverse neighborhood now brims with the homogeneity of an elite university.”

October 10, 2014

Staff Picks: Kids Tossing Guns, Phenomenal Hard-ons

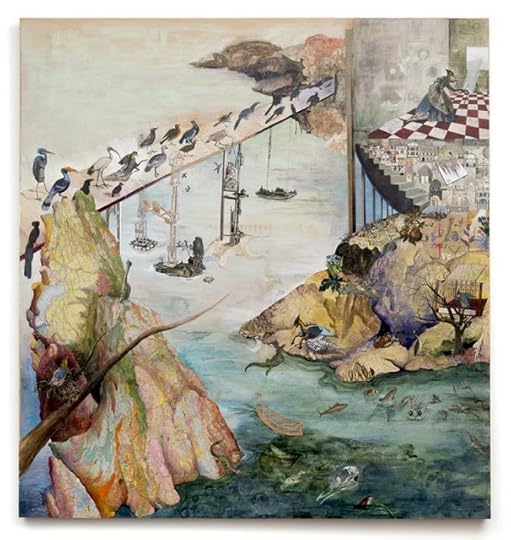

Josh Dorman, A Life Led, 2014, ink, acrylic and antique paper on panel, 60" x 56."

Despite the fact that the workmen next door have been playing the catchiest pop songs from the past thirty years for a few days now, I managed to tune them out long enough to read Jon McNaught’s Dockwood, a book that, though spare in dialogue, is oddly focused on sound, or, more accurately, on a symphony of silence. The book comprises two comics stories set in the titular British town, a leafy, suburban sort of place that is settling into the early days of autumn and into what seems like a permanent state of dreamy twilight. The first story follows a man named Mark through his day as a kitchen porter at a nursing home. The opening pages of the book are soundless, save the munch of a mouse eating a chip and tink of colliding hanging straps on a bus. But the quiet of early morning is surprisingly vivid. It creates a rhythm of reading—the pages are divided into tiny panels mixed in with larger ones—and plunges you instantly into the narrative. The second story, about a boy delivering newspapers, works according to the same principles. It’s a stunning effect. And McNaught, who is also a printmaker, makes each panel contemplate the smallest of life’s details. —Nicole Rudick

This Saturday is your last chance to see “Whorled,” Josh Dorman’s vast and imaginative solo show at Ryan Lee Gallery. Dorman paints vibrant, dreamlike landscapes and festoons them with found images: illustrations, fragments, and diagrams from old textbooks and catalogs, all of them from the seemingly prelapsarian period before photography, and all carefully (though still jarringly) collaged into the paintings. Parades of flora and fauna coexist with kids tossing guns; lakes are made of hammers, mountains grow from maps. You’d expect all this to devolve into chaos, a kind of jackdaw’s nest, but Dorman’s compositions are precise, even orderly, which makes them all the more uncanny—as beautiful as they are, the paintings evoke a state of basic contradiction that has a way of getting under your skin. —Dan Piepenbring

Even if it’s only an hour and forty minutes, Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja was one of the most difficult films I’ve sat through, and I’ve survived everything from Sátántangó to Snakes on a Plane. Moving at a glacial pace, with a plot as complicated as Waiting for Godot’s, the film follows the Danish surveyor Dinesen in nineteenth-century Patagonia as he tries to find his missing daughter in the otherworldly landscape. In long, carefully composed takes, Alonso declares his commitment to a minimalist cinema, one that blends narrative with documentary; the film is more about Dinesen’s relationship with the landscape itself than any miraculous reunion with his daughter. I walked out of the screening completely perplexed by the experience, but since then I haven’t been able to shake the film. It’s like a dream you hope to revisit until some sort of answer reveals itself. —Justin Alvarez

This week’s New Yorker includes “Scheherazade,” a gorgeous new story by Haruki Murakami with quiet undercurrents of the fantastic. Murakami writes of the intimacy between a housebound man, Nobutaka Habara, and his caregiver. Though Habara doesn’t seem to suffer from any ailment in particular, he’s always receiving the ministrations of Scheherazade, a woman he names after the queen in One Thousand and One Nights. She brings him provisions and takes him to bed, and then becomes a raconteur, telling him stories of lamprey eels or her preternatural youth, leaving Habara invested in her company but hyperaware of its mutability. Their relationship is resigned, mercurial, and that dynamic interests Murakami: “I occasionally think that, in our heart of hearts, we all may be seeking situations like this one—where our free will doesn’t apply and (almost) everything is determined by someone else, where each day must be lived according to the conditions that someone else has laid down … What interests me is trying to ferret out the identity that is so deftly concealed within the accumulation of such passive operations.” —Caitlin Youngquist

If you happen to be looking for a short-story collection that features talking fish, immortal dogs, and girlfriends that turn into fat, hairy men at night, Etgar Keret’s The Nimrod Flipout is your best bet, maybe your only bet. The Israeli author’s particular brand of magic realism comprises equal parts normalcy and sleeping pill–induced dream puddle. But underneath the phantasmagoria of these stories and their unusual titles (one story is called “Actually, I’ve Had Some Phenomenal Hard-ons Lately”) lies an entirely serious commentary that grapples with issues of emotional expression and individuality. The collection’s deeper implications are charmingly concealed but are definitely present—just ask the fish. —Alex Celia

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers