The Paris Review's Blog, page 652

October 21, 2014

Your Newspaper: Writer’s Cut, and Other News

A handyman at the H. C. Johnson Grocery Store in Robertstown, Georgia, reads a newspaper, July 1975. Photo: National Archives

“There’s an endless appetite among film buffs for the contents of the cutting-room floor. We’re forever being offered outtakes and alternative endings and ‘director’s cuts’ of movies. But what do newspaper editors excise from raw copy destined for the printed page? What would a ‘writer’s cut’ look like?”

Area Novelist Super Pissed He Keeps Getting Compared to Cormac McCarthy: “This is testament to the McCarthy hegemony, to how wholly he dominates an entire sector of American fiction, and to how he has usurped our understanding of a certain literary pedigree. Write a novel with a specific poetical register adequate to the task of addressing nature and redemption, one which includes the sanguinary madness of men, and McCarthy is the artist languidly at hand for every reader itching to make a connection.”

“It was difficult sometimes to eat lunch with Robert because his makeup was so realistic. His brains were hanging out of his prosthetics.” An oral history of A Nightmare on Elm Street.

Photographers have found themselves “in the age of citizen Instagrammers, in which phones carry an endless roll of virtual film, and there are so many photos that we think we’re entitled to have them for free.” What to do? Litigate!

Our poetry editor, Robyn Creswell, on the novels of the Lebanese writer Rabih Alameddine: “The heroes of his fiction are all misfits of one sort or another. They rebel against what they take to be the tyrannical conventions of Lebanese society—its patriarchy, its sexual norms, its sectarianism. In most of his novels this revolt takes the form of flight to America … In America, Alameddine’s characters discover that the pleasures of individualism often turn out to be empty, and their host country’s foreign policy, particularly its support for Israel, is a constant irritant. So their emigration is only ever partial; the old world haunts all their attempts at reinvention.”

October 20, 2014

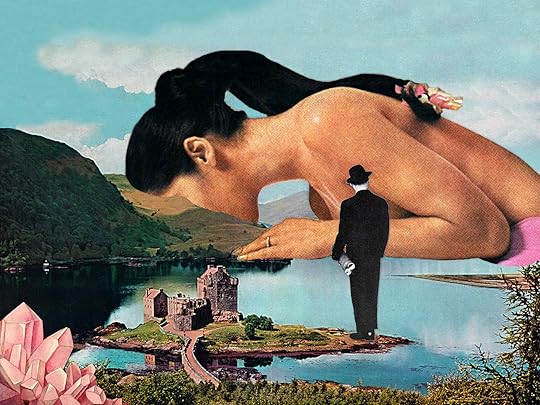

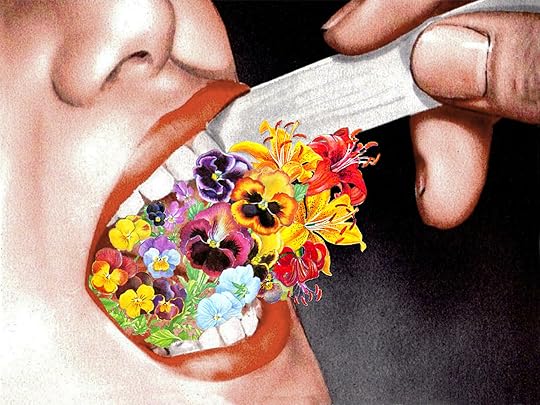

Two Collages by Eugenia Loli

Eugenia Loli, The Day TMZ Got Hold of Her Sex Tape, 2014, 6" x 8"

Eugenia Loli, Gardens Flower in Her Blooming Breath, 2014, 8" x 6"

To Suit the Occasion

School of Martin Van Meytens, Coronation Banquet for the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II in Frankfurt, 1764.

In the spring of 2000, The Paris Review published an issue dedicated to poetry—dubbed, in fact, The Poetry Issue—including a series of prompts for poets and an essay by Robert Pinsky, who was then the U.S. Poet Laureate. Pinsky is seventy-four today; an excerpt of his essay, “Occasional Poetry and Poetry on Occasions,” follows.

What does it mean that so many distinguished and gifted poets responded to the somewhat goofy games and assignments suggested by The Paris Review for this issue? Not just willingly, but with spirit, they have composed poems to strange titles like “An Empty Surfboard on a Flat Sea” and “Lavatory in a Cathedral,” written commentaries on worksheets—written, in other words, to suit the occasion.

Occasions have elicited poems throughout history: coronations, birthdays, weddings, victories, executions, seductions (successful and unsuccessful), births, and deaths have their genres and great examples. Poems responding to specific circumstances have ranged from the agonized majesty of Yeats’s “Easter 1916” to the humblest good-humored verses produced for benign laughs at the office retirement party or a family anniversary. Donne wrote “the Anniversaries” on assignment and Marvell’s “Upon Appleton House” is the most gloriously entertaining in-group, after-dinner speech in the language.

Does this play of talent in response to occasions and assignments tell us anything about the art of poetry? Many poets have been unwilling or unable to write on assignment, in response to circumstance but even their work has been used after the fact—quoted in speeches, inscribed in stone, read at the graveside or after the victory. (Anyone who writes or studies poetry can remember being asked for something suitable to be recited at a wedding or a funeral.)

Occasional poetry is a reminder that poetry is related to speech a little bit in the way dance is related to walking: it is more playful, as well as more serious. Poetry’s medium is not merely light as air, it is air: vital and deep as ordinary breath.

The title of Poet Laureate, always dangerously inviting to comedy and satire, more than a little absurd, may be linked to the idea of the occasion: just as there is for some reason no Photographer Laureate or Novelist Laureate or Choreographer, we do not speak of occasional photographs (unless they are called “snapshots”?) or occasional novels or occasional dances.

There is no occasional acting or dancing because performance is itself an occasion. But a poem creates or calls for an occasion: the re-creation of its words in the reader’s voice. The poem makes the occasion of its reading, its invited taking-place in the reader’s actual or imagined breath. This creation of occasion can be described as both playful and formal.

A poem is something that happens. It is not words or characters on a page, and it is not a performance by the artist: the artist makes the means or occasion for the poem to happen in the reader, an action spirited into being. This process from maker to work to recipient, a process so ancient it seems natural, is itself a human creation, like any other social form.

[…]

Expectation is created artificially, in a way, by rhythm and thyme. The rhythmical crooning or rocking of the miserable or abandoned child is described by psychologist as self-stimulation: the cadence creates a kind of homemade Other. Occasional poems may recognize or manifest something like this principle: they tend to be formal. The world occasion has its root in the Latin word for falling: the assignment or situation falls to a certain person, or across someone’s path. A certain sound falls to a certain meaning, and from the chance association of grunts and idea, art can be made …

The occasion, the challenge of a reality that falls into one’s path, offers something like collaboration—between the enteral world and the self, between language and intention—is the hoped-for event of a poem.

Read the whole piece in Issue 154.

Rote Learning

A postcard of the Bleecker Street IRT stop, 1905.

“I’ve never seen the point of New York,” someone said to me last week, in a foreign city, upon learning that it was my hometown.

I must confess to being nonplussed by this. I hadn’t fielded such an idiotic remark since middle school. Back then, I would have responded in kind with some nonsense—“Well, since it’s not pyramid-shaped, neither have I,” or something about John Stuart Mill, if I knew about him—but now this did not come so easily. Most of us have long since learned that there’s not much sport in breaking the fine-print clauses of the social contract.

And most of us learn the hard way. My most shameful memory is of creeping around a tree, perhaps in second grade, at Reynolds Field, and hissing, “Candy is dandy, but liquor is quicker,” at a mystified five-year-old. I knew instantly that I had not conjured the mystery and allure I’d been going for; that I was, in fact, an ass. I have never admitted that before. I wonder if that kid remembers it. I really hope not.

But now I am a grown-up. So I quoted to him one of the few things I know by heart:

On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy. It is this largess that accounts for the presence within the city’s walls of a considerable section of the population; for the residents of Manhattan are to a large extent strangers who have pulled up stakes somewhere and come to town, seeking sanctuary or fulfillment or some greater or lesser grail. The capacity to make such dubious gifts is a mysterious quality of New York. It can destroy an individual, or it can fulfill him, depending a good deal on luck. No one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky.

I finished. We stared at each other blankly.

“That was E.B. White,” I said.

“I meant it rhetorically,” he said.

Being Discovered: An Interview with Calvin Tomkins

Gerald and Sara Murphy with Cole Porter and the Murphy’s friend Ginny Carpenter, in Venice, summer of 1923. Gerald had come to collaborate with Porter on their ballet Within the Quota.

In the late fifties, Calvin Tomkins, a longtime staff writer for The New Yorker, moved his family from New York City to a little community on the Hudson River called Sneden’s Landing. “The houses are built on the side of a hill fairly close together,” Tomkins told me by phone this past summer, “but in those days there were no real property lines. Everybody knew each other, and the kids wandered all over.”

Tomkins’s two daughters, Anne and Susan, eventually found their way to Gerald Murphy, then in his sixties, pruning his rose garden. As kids do, they struck up a conversation with Gerald, and when Tomkins and his wife caught up with them, Sara, Gerald’s wife, emerged from the house, taking orders for ginger ale.

“The Murphys didn’t talk about the past in those days, and it was some time before I realized they were the people F. Scott Fitzgerald had used as models for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender Is the Night,” Tomkins wrote in 1998. In the twenties and early thirties, the couple, along with their three children, spent part of the year in the south of France, on the Riviera, and the rest of it immersed in the salad days of modernism and surrealism in Paris, where they had befriended, among others, Picasso and his first wife, Olga Khokhlova; Ferdinand Léger; Dorothy Parker; Cole Porter; the Fitzgeralds; the Dos Passos; and the Hemingways. It was a fascinating life, though shrouded in mystery and tragedy.

Gerald Murphy with Picasso.

Tomkins urged Murphy to write a memoir, but Murphy “scoffed at the notion … he had too much respect for the craft of writing, he said, to attempt something which could only be second-rate.” Tomkins reported the piece instead. It was called “Living Well Is the Best Revenge,” a reference to the seventeenth-century poet George Herbert’s mordant epigram, which Murphy had once jotted down on a piece of paper. The piece ran in The New Yorker on July 28, 1962. By the time Tomkins had expanded it into a book, in 1974, “Gerald had been dead for ten years, and Sara, who died in 1975, was no longer aware of the world around her.”

Fortunately, Tomkins was, and Living Well Is the Best Revenge remains one of the most ingeniously reported profiles of the Lost Generation, with the Murphys serving to illuminate the nearly century-old American expat scene that flourished in Europe between the two World Wars. The book had gone out of print until MoMA reissued it earlier this year in a beautiful flex-cover format. I spoke to Tomkins, who’s now eighty-eight, about the Murphys’ past, Gerald’s career as an artist, and his reporting for the book.

Before you got to know them, did you know much about Gerald and Sara Murphy?

I had heard about them. The Murphys were legendary because people knew vaguely about their life in Paris in the twenties, but nobody really knew them very well. They had a party a year, I think—a garden party with candles in paper bags. More or less the whole community was invited. But otherwise, they kept to themselves. We were all very curious about them. It seemed to us that we had these exotic creatures living in our midst.

You had read Tender Is the Night—Fitzgerald’s fourth novel, published nine years after The Great Gatsby—by happenstance before meeting them. At the time, the novel had been all but forgotten.

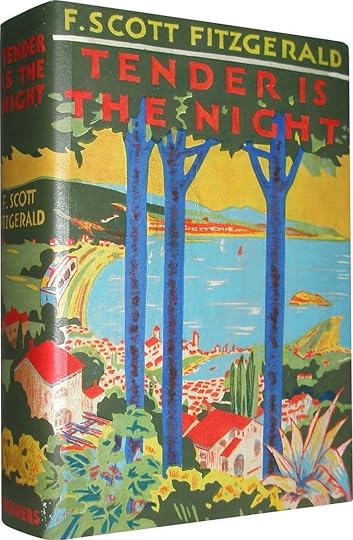

The first edition of Tender Is the Night, 1934

Yes, my wife at the time and I had gone to live in Santa Fe for almost a year. I was writing a novel and we were actually caretakers of a house whose owners had gone with their children to France for the summer. There was a nice library there. One of the books I pulled out to read was Tender Is the Night, which I had not read before. I had read Gatsby in college and a few Fitzgerald short stories, but I had never read Tender. It was one of those reading experiences that you get maybe two or three times in your life, when a book just takes you over. I was deeply immersed in that book and in the world it had conjured up. I still think it’s by far his best work.

But as you know it was not a success at the time. It came out during the Depression, and it was considered frivolous—a narrative about rich people on the Riviera, with no relevance for the period people were living in. But ever since then it’s been gradually assuming more and more of a place in American literature.

I was really upset by the book. It made me deeply sad and troubled because I became emotionally involved in the life of those two people, Dick and Nicole Diver. It seemed like such an extraordinary coincidence that a few years later I would move next door to the people who were their models.

You make a number of interesting observations throughout Living Well, most notably that some people, including the Murphys themselves, felt that Tender was a disingenuous representation of that period, and of Gerald and Sara in particular. More than fifty years after reporting this story, how do you remember Fitzgerald’s relations to the Murphys?

Gerald and Sara were not at all happy when they found out that Scott was writing a novel about them. Scott’s way of going about it was extremely annoying. He would ask them intrusive questions, like, How much money do you really have? and How did you get into Skull and Bones at Yale? They felt that many of his questions were quite hostile. He had a somewhat disapproving attitude of them by then. They had met in Paris in 1922 or 1923, and the Fitzgeralds started coming to the south of France largely because the Murphys were there.

Gerald and Sara were not at all happy when they found out that Scott was writing a novel about them. Scott’s way of going about it was extremely annoying. He would ask them intrusive questions, like, How much money do you really have? and How did you get into Skull and Bones at Yale? They felt that many of his questions were quite hostile. He had a somewhat disapproving attitude of them by then. They had met in Paris in 1922 or 1923, and the Fitzgeralds started coming to the south of France largely because the Murphys were there.

For several summers they were very close. Gerald admired Fitzgerald as a writer. He thought that Gatsby was an extraordinary achievement, and that some of the short stories were first-rate, but he didn’t have a great deal of respect for the work that Fitzgerald was doing then. He was writing mainly for the Saturday Evening Post—short stories. A lot of them seemed to Gerald too commercial, and not up to the standards of his earlier work. Fitzgerald never seemed to Gerald and Sara to be a writer on the same level as Hemingway, who took himself far more seriously. They felt that Hemingway was the important writer, the one who was breaking new ground in prose. I don’t think they had the same feeling about Scott, and as a consequence, the idea that he was writing a novel about them did not fill them with joy.

Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald in the south of France, ca. the late twenties.

Gerald was a painter, and his career seems to have been cut short by the tragedy of his two children passing away. You mention that his art, most of which was produced in the twenties, was, in many ways, proto-pop art. Do you think Murphy fits in with the modern pop of the sixties? Was that something he was interested in?

He became interested. He had not really thought much about art in a long time. He had stopped painting in the early thirties when his younger son contracted tuberculosis, and he devoted his whole life to caring for and trying to save the child. He never took it up again. Apparently he didn’t even want to talk about it. His friends told me he just pushed it aside.

As I was getting to know him better in the early sixties, he was very interested in some of my artist profiles. We talked about them quite extensively. Partly as a result of that he became interested in Rauschenberg and Tinguely, and a lot of people I was writing about. His interest in art itself was revived. I remember him becoming quite interested in young European artists of that period, as well. It was a big change in his life. It was as though, after all of these years, he was finally able to take an interest in the thing that had utterly consumed his interests in the twenties. His whole life had changed when he got to Paris in 1921 and he saw, for the first time, paintings by Braque and Picasso and Miró in Paris galleries. That was what triggered his interest, and he began to think that this was something that he could do, too.

Why do you think he produced so little work?

He didn’t really start painting on his own until 1922. Some of the earliest paintings were extremely large. There was one that was eighteen feet tall by twelve feet wide. He had studied in Paris with Natalia Goncharova, the Russian émigré artist, who introduced him to the principles of abstract art. It took him a long time to finish each one. There were a lot of preliminary sketches and studies and drawings, and he worked very slowly. Each of these paintings took him maybe six or eight months. I think we have to realize that he wasn’t just doing that. He was also leading a very active life in Paris in winter, and in the south of France in summer. He told me he spent no more than three hours in the studio per day. The total of his production in those ten years was fifteen paintings.

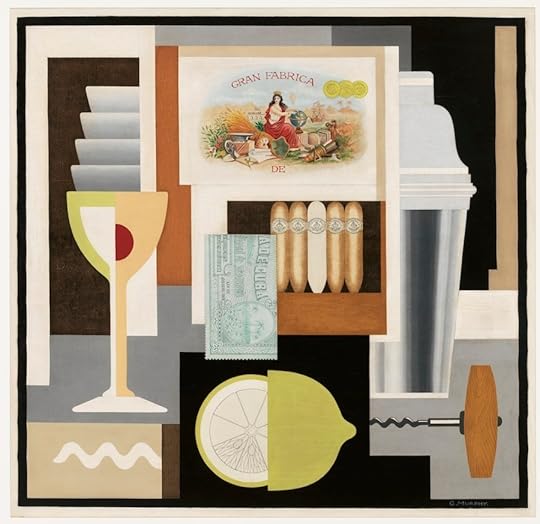

Gerald Murphy, Cocktail, 1927, oil on canvas, 29 1/16" x 29 7/8". The Whitney Museum.

Gerald Murphy, Razor, 1924, oil on canvas, 32 1/2" x 36 1/2". Dallas Museum of Art.

Gerald Murphy, Villa America, 1924, oil and gold leaf on canvas, 14 1/2" x 21 1/2". Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis.

Gerald and Sara had known each other since childhood.

Theirs was unlike any other marriage I’m aware of. They were so close that they seemed to complement each other in all sorts of different ways, although they were extremely different in just as many ways, too. As Gerald said, “Sara is in love with life and people, and I’m the opposite. I have a mistrust of life. I think life is only worth living when you do things to it. What you do with your mind is what counts.” Sara in a way was much more open, friendly, unguarded. Gerald had a kind of puritanical reserve. There was really that spontaneous, effervescent, unpredictability about Sara, while Gerald’s approach was much more carefully thought out. There was a mating of temperaments.

Do you think Gerald didn’t want to talk about being a painter because it brought back memories of his son, and not because he thought he was necessarily a failure?

Gerald and Sara, Cap d’Antibes, 1923

Sometimes I think Gerald never realized how good he was, but then at other times I feel he must have. Léger and also Picasso were very positive about what he was doing. Léger said he was the only American artist in Paris. You can’t hear that sort of thing from people of that caliber without it registering in some way.

One of the things I’ve often regretted is that I didn’t talk to him more about his painting. I’m afraid at that time I didn’t realize he was a serious artist. It was only later that I began to realize how good he had been. There were two of his paintings in an upstairs bedroom, but I was never encouraged to look at them. Another one was rolled up in the attic. Gerald just didn’t talk about them. What really broke him out of that was an art historian named Douglas Macagy, who had worked once for the Museum of Modern Art. He did a show called “American Genius in Review” about four relatively forgotten artists—Tom Benrimo, John Covert, Morgan Russell, and Gerald Murphy.

Macagy had heard about Gerald Murphy from one of the other artists. He looked up the work and fell in love with it. He not only put Gerald in the show—which was held in 1960 at the Dallas Museum of Art, where, at the time, he was the director—but he also wrote an article about him for Art in America. This article really brought Gerald’s art to the attention of a lot people. All this was just happening at the end of his life—the beginnings of a rediscovery of his work. Gerald joked to me, I’ve been discovered. What does one wear?

J. C. Gabel is a writer, editor, and publisher living in Los Angeles. He grew up in Chicago.

Hang Your Quiver on Your Wagon, and Other News

An illustration of the Amazons from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493.

In 1882, Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde spent an afternoon together. They had some homemade elderberry wine and talked about how to be famous.

And in 1817, Keats, Wordsworth, and Charles Lamb had dinner. Lamb said repeatedly, “Diddle idle don / My son John / Went to bed with his breeches on.”

Winning the Nobel Prize causes an intense, nearly insurmountable euphoria. But according to Patrick Modiano, there is one way to magnify this sensation: by having a family member who hails from the same country that gives the prize. “It gave me even greater pleasure because I have a Swedish grandson … It’s to him I dedicate this Prize. It is, after all, from his country.”

Historically, fiction has afforded writers the chance to break taboos—under the guise of the fictive, one can “talk about potentially embarrassing or even criminal personal experiences without bringing society’s censure on oneself.” So what happens when taboos fall away? “It could be we are moving towards a period where, as the writer ‘gets older’ … he or she finds it increasingly irrelevant to embark on another long work of fiction that elaborately reformulates conflicts and concerns that the reader anyway assumes are autobiographical. Far more interesting and exciting to confront the whole conundrum of living and telling head on, in the very different world we find ourselves in now, where more or less anything can be told without shame.”

The sexual congress of the Amazons “was robust, promiscuous. It took place outdoors, outside of marriage, in the summer season, with any man an Amazon cared to mate with … The sign for sex in progress was a quiver hung outside a woman’s wagon.”

October 19, 2014

This Week on the Daily

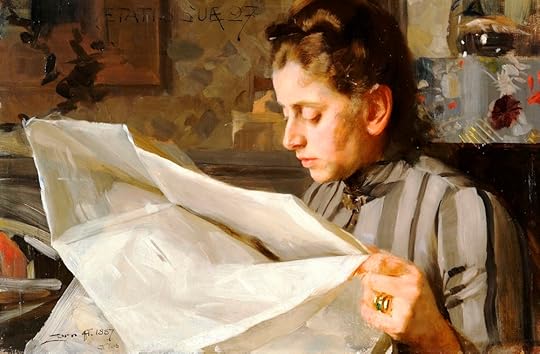

Anders Zorn, Portrait of Emma Zorn, 1887, oil on canvas, 15.8" × 23.9".

In a not-so-glamorous Las Vegas, Kerry Howley watches as a UFC fighter starves himself before weighing in, visiting all-you-can-eat buffets just to see everything he’s missing:

In the twenty-four hours between weigh-ins and the fight, Erik would gain twenty pounds, and he took great pleasure in imagining of what those pounds would consist. The Rio Buffet, he informed me, offered three hundred distinct dishes, seventy varieties of pie, an array of “bars,” including a sushi bar, a taco bar, and a stir-fry bar. He knew its small army of friendly spoon-holding servers, its fifty yards of curving black countertop, its unaccountable progression from sausage pizza to cocktail shrimp to scrambled eggs to lentil soup to crab legs to fried fish to sushi to green salad to gravy-slathered pork chops to honeyed ham to flank steak to barbecue ribs to burritos to tacos to waffles to spring rolls to dumplings to sweet-and-sour pork to eggs Benedict to bacon to one giant vat of ketchup to croissants to cubed mango to green-bean salad to seven kinds of lettuce to the gelato-and-pastries bar whose delights are too many to enumerate but which Erik would attempt to enumerate if given the chance.

Forrest Gander on the mysterious end of Ambrose Bierce, a hundred years ago: “According to witnesses, Bierce died over and over again, all over Mexico.”

Jeff Simmermon started a band with a guitar, a typewriter, and a pair of chickens who peck at toy pianos. They wanted to tour Japan. Al Sharpton got mixed up in it, and the whole affair provided a strange and invaluable lesson about artistic ambition and closure...

A new Italian novel takes Antony Shugaar back into the Years of Lead, a time of kidnappings and earthquakes and cholera epidemics: “Those who say they want to leave this country, or simply spend their whole lives saying they want to leave, do so because they want to save themselves. Well, I’m staying here. Because I don’t want to be saved.”

Plus, Sadie Stein’s dispatches from Berlin, where the chefs carry around Spinoza’s Ethics and the cabbies are fluent in Patrick Modiano; Terry Southern goes skeet shooting; and all of us get an irrefutable, statistical answer, at last, to that most pressing question: How often do Oscar Wilde’s characters fling themselves onto couches, sofas, and/or divans?

October 17, 2014

Staff Picks: Pirates, Policemen, Purple Skies

Jane Wilson, Hurricane Watch, 1990, oil on canvas, 35" x 40". Image via DC Moore Gallery.

In 1965, Jane Wilson made a print for The Paris Review. Hers was included in the first group offered by the magazine through its new print series; Wilson was joined in that inaugural endeavor by, among others, Helen Frankenthaler and Jane Freilicher, all of whom were cohorts in midfifties New York. Other than the print, I’ve only ever seen one of Wilson’s works, at a friend’s house—it’s a sizable painting of a landscape—but that’s been enough to make me covet her artwork. DC Moore Gallery has nearly a dozen of these landscapes on view right now, and they’re stunning. At almost six feet square, the paintings are large, and their size is amplified by terrific expanses of sky that take up most of the picture space. And what skies: a full range of purples, golds, blues, and greens—they appear as visions, as though you can see through time while only looking at the clouds. —Nicole Rudick

If you call Pirate Joe’s in Vancouver during off hours, you’ll be greeted by the store’s owner, Michael Hallatt, on the recording. “We do not sell Trader Joe’s products,” he says. “You might have heard we do; we don’t. That would be unfair to Trader Joe’s, to go down there and buy groceries from them. Say you bought like maybe a million dollars worth of groceries from them over three years, that would be grossly unfair.” But that’s exactly what Hallatt has done. Trader Joe’s doesn’t have a Canadian presence, so loopholes in a gray market allow Hallatt to resell Joe’s groceries. Priceonomics has the full story, from Hallatt’s early stock runs to Bellingham, Washington, and his subsequent ban from Trader Joe’s locations to his ongoing lawsuit with the grocery chain. At the end of the day, this is a love story between a man and a store. “Hallatt’s ultimate goal with Pirate Joe’s is to ‘bring’ Trader Joe’s to Canada—before he had the store he would call them and just petition them, and he has always promised to close up shop if they ever expand north. In many ways, Hallatt would count this as the ultimate victory.” —Justin Alvarez

The Melville House blog introduced me to The Policeman’s Beard Is Half Constructed, a—novella? discourse? medium-length prose work?—composed in the early eighties by an artificial intelligence called Racter (short for raconteur). Racter likely had some editorial assistance from good old-fashioned human beings, but even so, its work is affecting. There are moments when it has an eerily sophisticated grasp of these things we call “emotions,” all the complex longings that come with personhood: love, envy, hunger. And then there are moments when it sounds utterly robotic, almost autistic. A representative sample: “A sturdy dove flies over a starving beaver. The dove watches the beaver and fantasizes that the beaver will chew some steak and lamb and lettuce. The beaver spies the dove and dreams of enrapturing and enthralling pleasures, of hedge-adorned avenues studded with immense pink cottages, of streets decorated with bushes and shrubs. The beaver is insane.” —Dan Piepenbring

I was reluctant to read Don DeLillo’s Falling Man because I don’t remember how I felt on 9/11; I was barely ten. My mom, an EMT, pulled me out of school and dropped me home with my dad before rushing to the train station where first-responders were meeting. I was in McDonald’s eating a Big Mac when the South Tower fell. Eventually my brother and I got tired of watching my dad watch CNN; we went upstairs and watched Dumb & Dumber on a nine-inch television instead. DeLillo shows incredible tact and poise in his navigation of such a delicate subject. The novel is bookended by short scenes that take place during the attacks. The imagery is vivid, horrifying, and pea-soupy with detail. But DeLillo’s voice is strongest in his enigmatic mastery of the domestic. He doesn’t attempt to evaluate fallout and fear on a national level. Instead, he shadows a single survivor who returns to his estranged wife and child. The brilliance of Falling Man isn’t in shoving the reader back through the ashes of American flags but in exploring how the tragedy affected our understanding of memory, faith, and fear. —Alex Celia

In The Guardian’s “The Long Read” this week, Pankaj Mishra critiques The Fourth Revolution, a new book by John Micklethwait and Adrian Woolridge (both editors at the Economist). It’s beyond me how Mishra isn’t completely exhausted from his tireless defense against that most damaging and useless binary, “East/West.” “The twentieth century was blighted by the same pathologies that today make the western model seem unworkable, and render its fervent advocates a bit lost,” Mishra observes. Among the “advocates” he takes to task are “such Panglosses of globalization as Thomas Friedman” and Francis Fukuyama, whose pernicious “inverted Hegelianiam” must stop being consumed by the masses. Deftly showing how ISIS is “the latest incarnation” of “the blood-splatted French revolutionary tradition” and arguing that we must look to “historical specificity and detail” rather than support totalizing ideologies, Mishra provides a much-needed, sober reading of the state of the world today. —Charles Shafaieh

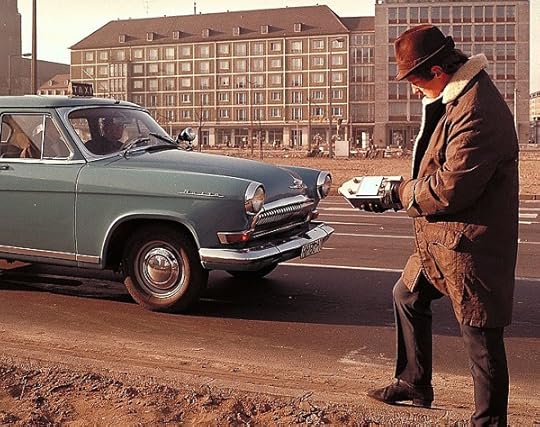

Globalization

A German cab in 1971. Photo: Eugen Nosko

You expect to feel humbled when you travel. Strange public transit, alien customs—add a language you don’t speak and it’s an immediately chastening experience. When the residents are so inured to your national arrogance and laziness that they don’t even visibly resent conducting transactions in English, it is more galling still. It’s sort of like being a baby—helpless, barely verbal, sleep deprived—except you can’t throw a tantrum. On the contrary, you are often expected to conduct business.

All this I expected. I was even impressed and charmed, on my first visit to Berlin, to find people eager to discuss Spinoza in restaurants and quote Schiller on the plane. Here is what (or who) I did not expect: my cab driver to the airport. It’s not that I was shocked by his exquisite English, his verbatim recitations of Kleist, or his strangely in-depth knowledge of the Frankfurt Book Fair (“I wondered about the Finnish literature they featured … Well, I try to keep up with such things.”) Here is what was deeply intimidating: he had actually read Patrick Modiano. And not just La Place de l’Étoile! “But not all thirty,” he said.

On the plane, I was seated between the aforementioned Schiller scholar and a teenage girl. I watched Maleficent and devoted considerable thought to the derivation of the term fruits of the forest, as used to describe that one mix of luridly red berries occasionally found atop old-looking tarts and cheesecakes. The teenager appeared to be writing diligently in a journal; I felt abashed anew. Then I glanced down at the page and, from her rounded, teenage-girl handwriting, I could see that it was a list of German words: a food diary. Before I looked away, I clearly saw a sentence beginning “Mein chicken nuggets.”

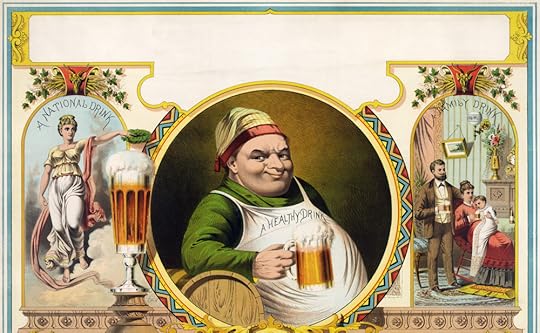

Too Much of a Good Thing

An ad by Mensing & Stecher, ca. 1870.

Fact: two hundred years ago today, eight Londoners drowned in a flood of beer.

I don’t know what else to say.

I guess I can tell you a little about it: how it began at the Meux and Company Brewery on Tottenham Court Road, where an enormous vat ruptured, unleashing more than a hundred thousand imperial gallons of beer; how the force of that gushing beer apparently caused the brewery’s other vats to rupture, thus sending some 1,470,000 liters of beer into the streets; and how that beer washed through a nearby home, killing a mother and daughter as they took tea. The Times reported that “inhabitants had to save themselves from drowning by mounting their highest pieces of furniture.” And the story goes that that the beer deluged right through a living room where a wake was in progress, killing a few mourners with intoxicating irony.

When I learned of the flood, my first question wasn’t “How many people died?” It was “What kind of beer was it?” And according to no less reputable a source than FunLondonTours.com, the answer is porter. Porters tend to be pretty strong, so anyone who managed to gulp down a few mouthfuls as he or she was enveloped by the beer wave … well, you can see where I’m going with this.

For more on the flood, check out Atlas Obscura.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers