The Paris Review's Blog, page 648

November 3, 2014

Brecht’s Breath, and Other News

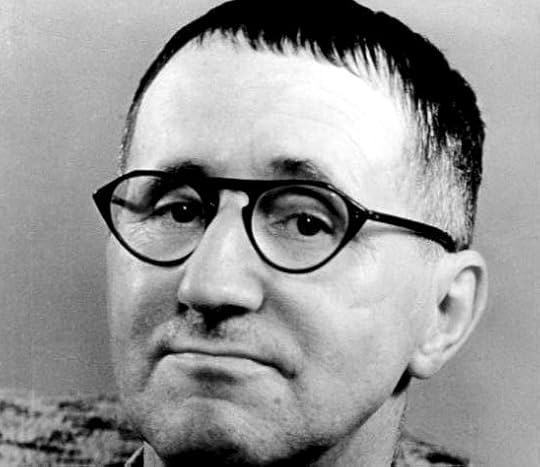

Better closed than open, that mouth. Brecht in 1954. Photo: German Federal Archives

On Brecht and hygiene: “He was physically repellent. He seldom washed and he smelled. He didn’t brush his teeth, and, consequently, many of his teeth decayed and fell out … Not surprisingly, he suffered halitosis—or rather, others suffered it. Brecht probably thought that, since imitation is the highest form of flattery, he was expressing his solidarity with the proletariat by being dirty. This, however, is insult rather than flattery … Brecht’s dirtiness was a form of condescension, the product of a lack of real interest in what poor people actually wanted.”

Please allow me to introduce myself: I’m a man of great wealth and taste. That’s why I’ve got this ten-thousand-dollar Rolling Stones art book sitting prominently, resplendently on my coffee table.

Lionel Shriver on the bitch goddess: “I’ve had to revisit a whole era of my own life, during which I imagined I was miserable. I was living in Belfast, and my career was on the rocks. Over this period, I lost my American publisher, and two novels thereafter were released exclusively in the UK. Reviews were agreeable, but sales meager … This is going to sound a stretch, but: those twelve years in the literary wilderness as a nobody, with a horribly high likelihood of getting nobodier? I think I was happy.”

Quick and easy advice for reading poetry (and making it, you know, fun): “Someday, when all your material possessions will seem to have shed their utility and just become obstacles to the toilet, poems will still hold their value. They are rooms that take up such little room.”

The cinema: Should we give a fuck? “We all know that movies make a lot of money for a few people, provide a living for many, and help most of us pass the time—which is fine, as far as it goes. But beyond that, why should anyone care?”

November 1, 2014

This Week on the Daily

Detail from Carl Ostersetzer, Wirtshauspolitik, 1914, oil on panel

James McGirk writes from Oklahoma, where plans for a public Satanic ritual expose cultural fault-lines and religion seems to permeate every aspect of life. “They want your soul and they’re willing to fight for it.”

*

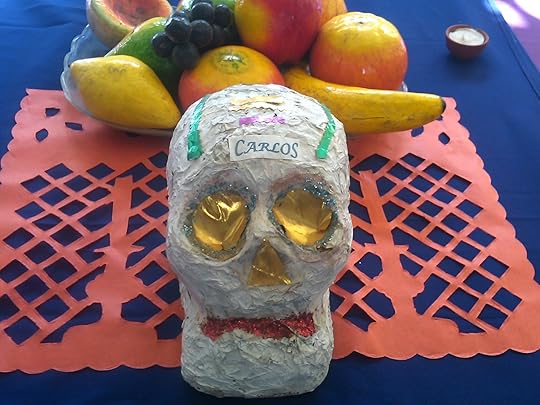

Preparing for the Day of the Dead, Rex Weiner reports from Casa Dracula, a haunted house for writers on the Pacific Coast of Mexico.

*

Looking at the controversy surrounding The Death of Klinghoffer, Michael Friedman reminds us that grand opera has always been intertwined with the politics of the day.

*

Dwyer Murphy interviews David Gordon: “My protagonists eat a lot of Chinese food and go to a lot of cafés. People tend to have cats in my stories, and the women have long fingers. I have no idea where this stuff comes from. I have no lost love with long fingers.”

*

Now that the World Series is over, Adam Sobsey has a simple request decades in the making: “Let’s get Dock Ellis into the Hall of Fame.”

*

Plus, Sadie Stein looks at the outmoded fun on display in Cupid’s Cyclopedia; what scares the staff of The Paris Review? (Taylor Swift, among other things); and Thackeray’s doodles reveal his macabre side.

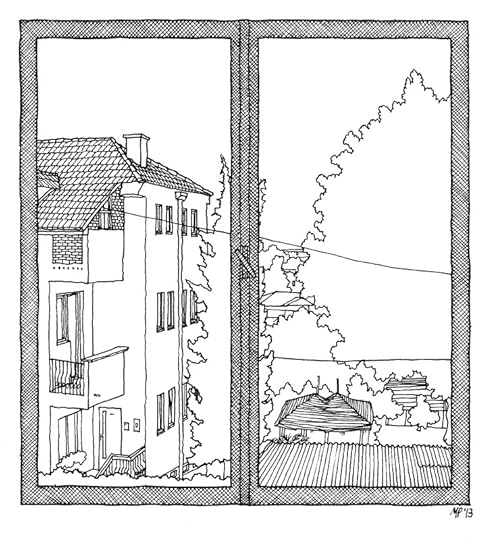

Announcing Our Windows on the World Contest

Matteo Pericoli’s drawing of the view from Lidija Dimkovska’s window in Skopje, Macedonia.

For the past few years, readers of the Daily have enjoyed an occasional series called “Windows on the World,” featuring Matteo Pericoli’s intricate pen-and-ink drawings of the views from writers’ windows around the world. Now those drawings are available in a book—Windows on the World: Fifty Writers, Fifty Views—and we’re celebrating with a contest. You can have your view illustrated by Pericoli, too.

Starting today, submit a photograph of the view through your window—including the window frame—along with three hundred words about what you see, to contests@theparisreview.org. Submissions will be judged by the editors of The Paris Review and Penguin Press, and by Matteo Pericoli. The winner will receive Pericoli’s original sketch and have his or her essay published on the Paris Review Daily. Five finalists will receive signed copies of Windows on the World.

For all the details, click here, and then get cracking: we‘re only accepting submissions until November 15.

October 31, 2014

If I Had a Ribbon Bow

From the cover of In a Dark, Dark Room.

As we all know, the world divides, evenly or otherwise, between those of us who grew up reading In a Dark, Dark Room and those who did not. Those of us who have read it (I got my copy at one of those sponsored school book sales, noteworthy for its bake sale and wealth of Klutz-brand books, one of which came with a Koosh ball) will never look at a green ribbon the same way again.

Spoiler alert for “The Green Ribbon”: Girl has green ribbon around her neck. Grows up, marries, ages, dies. Ribbon is untied, head falls off. It is a perfect scary kid’s story: simple, terrifying, pleasantly idiotic. Certainly, I didn’t feel it to be in any conflict with the basic facts of anatomy. Certainly not doll anatomy. In Alvin Schwartz’s 1984 I Can Read! version, the girl—Jenny—looks sort of like Laura Nyro and rocks a really good look.

If I have a beef with most modern fright-fests, it’s that they’re too complicated: over-plotted, spilling over with various malignancies and kinds of dark magic. “The Green Ribbon” is an antidote to this. Unlike, say, the Koosh ball, it has aged well. After its fashion, it is the perfect scary story. But you don’t have to take my word for it!

Disturbing Innocence

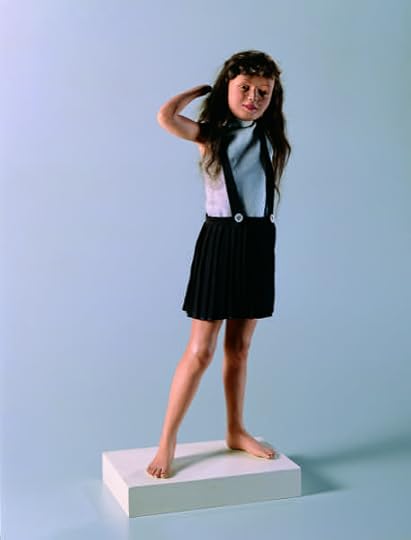

Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, Kirsten, Star, 1997.

James Croak, Dirt Baby, 1986.

Morton Bartlett, Untitled (Doll in Blue with Pleated Skirt), undated.

Peter Drake, Siege of Syosset, 2007.

Jake & Dinos Chapman, Doggy, 1997.

James Casebere,

Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County) #9, 2011.

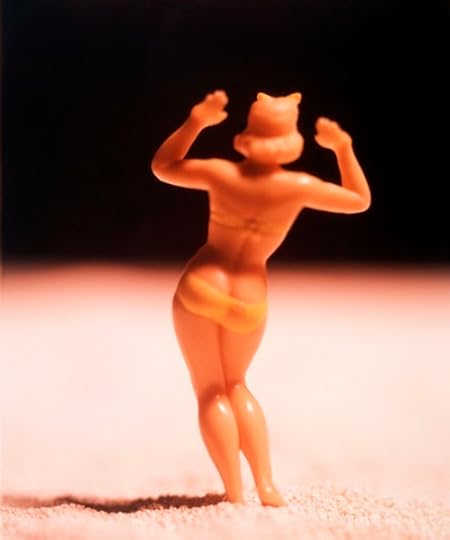

David Levinthal, Untitled (Woman with arms raised from behind), 1989.

Dare Wright, Edith And Big Bad Bill: Little Bear To The Rescue, 1968.

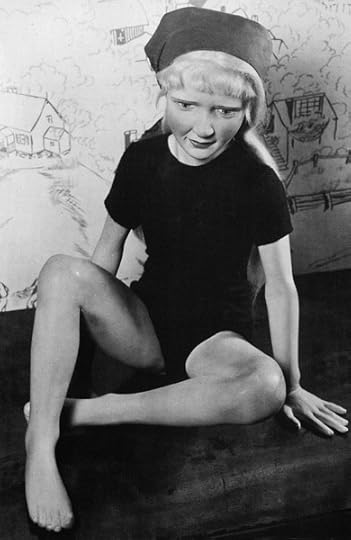

Morton Bartlett, Untitled (Sitting Pre-Teen Girl in Leotard with Painted Background), 1950.

Morton Bartlett, Untitled (Young Girl with Bow and Dress and Stuffed Dog), 1950.

The artist Eric Fischl has curated “Disturbing Innocence,” a group show on display at the FLAG Art Foundation through January 31, 2015. More than fifty artists, historical and contemporary, are represented in the exhibition, which features work with a focus on surrogates—mannequins, dolls, robots, toys—and “presents a subversive and escapist world at odds with the values and pretensions of polite society.”

Fischl says in a preface to the catalogue:

Curiously, “toy,” “robot,” “mannequin,” and “doll” are all nouns with negative connotations embedded in their definitions, including phrases like “something of little value,” “non-important,” “subservient,” “a non-entity,” “without original thought,” “controlled by others,” “a pretty girl of little intelligence,” and “disposable.” The very thought of this goes against the profound experiential impact these supposedly trivial attachments have had on our imaginations and within our emotional development as children. It flies in the face of what we know from our own essential experience with our toys. The difference between children playing with their toys and adult artists using toys and other surrogates for their art, the way that male and female artists use these surrogates differently, are the crux of this exhibition.

Letter from Casa Dracula

A haunted house for writers on the Pacific Coast of Mexico.

Photo: Billy Sheahan

The writers are coming.

But first, we must get our house in order, because, ay carajo, Hurricane Odile’s rude visit left the place in a shambles—muy malo, as our property manager Paula told us by e-mail a few days later, after Odile’s wrath had passed and the Internet had been restored to our dusty little town on the Tropic of Cancer. The Day of the Dead approaches, and while so many are mourning their losses and celebrating their miraculous survival, we have much to do.

Our house, the house in question, is known as the Casa Dracula, an ancient two-story, adobe-brick landmark in Todos Santos, Baja California Sur. Odile was a category-four hurricane and she made a direct hit on the southern Baja peninsula last month.

The writers are the attendees of the 2015 Todos Santos Writers Workshop, taking place for the second year at Casa Dracula at the end of January. They’ll draw inspiration from the old haunted house, a noble structure built around a courtyard in 1852 by a local sugar baron. Legend has it the Casa was given its name by the barrio children in awe of the imposing, long-vacant, bat-infested structure, and it was later officially designated such by the town—a town with, in fact, its own official designation as a Pueblo Mágico by the Mexican government. Nobody is sure what that means exactly, a “pueblo mágico,” but in Mexico the exact meaning of anything is not necessarily the point. The poetry is what matters, and Todos Santos is known for its lyrical beauty—a lush oasis bounded by mountains to the north, an oddly verdant desert, and a Pacific Ocean coastline alive with whales spawning, with baby sea turtles emerging from sandy nests on certain moonlit nights to begin their tireless journey to the sea, and with surfers skimming the waves by day.

Todos Santos is also known for its brujería, the gentle witchcraft practiced in the region since before padre Jaime Bravo arrived to build the Misión Santa Rosa de las Palmas in 1723 and to preside with his Jesuits over the errant souls of the indigenous Guaycura. Herbs are gathered, special candles lit, incantations repeated, and spells cast by brujos and brujas for good or bad. The coyotes roaming Todos Santos neighborhoods at night appear as restless emanations of a town of shape-shifters and tricksters. This is a good environment for writers: writing is a sort of shape-shifting trick we play on others, or a spell we cast on ourselves.

To invoke the mágico of our workshop and to assist in the exorcism of Odile, we have invited Donald Cosentino, professor emeritus of World Arts and Cultures at UCLA, to preside over an exploration of “the persistence of mythic characters in contemporary storytelling,” as he puts it. Cosentino identifies the trickster as “Hipster, Rapster, Prankster, Shit Kicker, Psychopath, Hell’s Angel … the oldest and most ubiquitous of all protagonists, whose present-day avatars range from Randall Patrick McMurphy to Bugs Bunny.” A world-renowned expert on Haitian vodou, Dr. Cosentino will enlist the friendlier spirits of the Casa Dracula in our group purpose, and probably some of the more mischievous ones as well.

An altar at Todos Santos’s Casa de la Cultura for the Day of the Dead. Photo courtesy of the author.

Before everyone arrives, though, we’re preparing the house for the Día de los Muertos on the first of November. This is no gringo Halloween. It’s a dead-serious celebration of the spirits that walk among us. The graves in the panteón, just above town, will be swept clean, washed and decorated with flowers and photos of the deceased. Plates of their favorite food will be set out on the sandy mounds and cement-block tombs to satisfy their unearthly hunger, beer and tequila to slake their thirst in death, as in life. It is an appropriate date to be once again in Todos Santos—not just one, but all saints—and to be at home in our beloved Casa Dracula.

We will be surveying the destruction wrought on the town by Odile’s terrible winds, in which—¡qué milagro!—nobody in our town died. We hear the electricity is restored and the water is running. The Palapa Society is raising funds for repairing the homes of many wiped out by the storm. We’ll be assessing the damage to our Casa and its gardens, lament the stump in the courtyard where the stately tamarind tree once stood to shade us on the hottest days. Renee, our jardinero, has cleared it away with his merciless chain saw.

We will be renewing our ties to the house, to the ghosts that inhabited the nineteenth-century pile of bricks when we purchased it thirty years ago from the great-great-granddaughter of the original owner, as well as to our own ghosts, installed in the house since. Will they come forth to welcome the writers in January? Burning a little pile of herbs, whispering a few sacred words, and pouring a shot of tequila for good measure, we perform the trickster rituals that get us through the years. “You hope for inspiration whatever the circumstances,” said García Márquez.

We shall be ready—¡ojala! We go to prepare, and will report back.

Rex Weiner, a journalist who divides his time between Los Angeles, New York City and Todos Santos, BCS, is a co-founder and executive director of the Todos Santos Writers Workshop.

What Scares The Paris Review?

From a 1939 Dutch workplace safety poster by Gé Hurkmans.

The book I find myself most often recommending—Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps—is perfect reading for tonight, or for any chilly evening, when the fallen leaves outside have begun to mold and decay in wet piles. I may originally have read it in the summer, but so thoroughgoing is its tone of paranoia, cold, rot, and subsumed violence that you can’t easily separate yourself from the refracted narrative of the book’s protagonist, an ESP-endowed teenage girl running with a group of “vampire hobo junkies” in the Pacific Northwest. She’s searching for her foster sister, Kim, along the “highway That Eats People,” and the novel reads like an Orphic descent into a bad dream within a bad dream, with the physical landscape—loamy, waterlogged, and dank—doubling as the psychic landscape: “The land was not to be trusted. Its climate had the potential to make those teetering on the edges of decency spill over into murderville … Psychos tried to plug up cracks with bodies, cloth, whatever’s at hand.” —Nicole Rudick

Scary things I remember: a hand coming out of a box on The Electric Company, the dying boar on the cover of my parents’ Four Seasons LP (made them skip the Autumn movement), “Ode to Billy Joe,” reading The Dead Zone by flashlight under the blanket at camp, The Shining (movie), The Exorcist (book), the prophecies of Nostradamus (had to hide the book), Let’s Scare Jessica to Death on TV on a Sunday afternoon (Sunday afternoon movie), the Twilight Zone movie (had to leave theater), Eraserhead late at night alone in my parents’ bedroom (“You are sick!”), the diner scene in Mulholland Drive (the compressed audio), the distortion of Laura Dern’s face in Inland Empire, “Don't Crash” by Front 242, in the listening room at the school library (do these still exist?), Don’t Look Now, Francis Bacon, Fleetwood Mac, The White Ribbon, the dream sequence in Amour, and the scary-doll movie Sadie made me see last month. The other things I’ve managed to forget. —Lorin Stein

Taylor Swift’s “Track 3” recently made it to number one on Canadian iTunes. The track was a glitch, eight seconds of white noise. I’m open-minded, so I gave it a try, and by lunchtime I realized, rather suddenly, that “Track 3” was stuck in my head; Swift seemed to follow me into the void, filling it with something familiar yet indefinable. In “Track 3” she’s mastered the Freudian uncanny, something that’s frighteningly unknown but brings us back to something familiar. Freud once quoted Ernst Jentsch: “One of the most successful devices for easily creating uncanny effects is to leave the [listener] in uncertainty whether or not a particular figure … is a human being or an automaton.” I maintain that Swift released “Track 3” in all its uncanniness to confess that she is, in fact, an automaton. If you think your costume is good, stew on that: Swift’s has been better, every day, since 1989. —Alex Celia

Alex jests, but I do not: I really adore Taylor Swift. And that’s scary. She’s just released the best pop record of 2014: the most exhilarating, the most addictive, and also the most inscrutable, the most frustrating. Carl Wilson, the best pop critic writing today, understands—his review of 1989 uses Swift’s famously undisclosed bellybutton as a metaphor through which to apprehend the entire Swiftian zeitgeist. He gazes into her navel “as umbilical nub,” “as median point and sore spot,” “as Jell-O shot dispenser,” “as contemplative locus,” “as camera aperture,” “as teen-pop erogenous zone,” “as pretty hate machine,” “as the whitest thing on Earth,” and “as the omphalos of capital,” among others. No one has better identified the qualities that make her such a vital force in pop, so lucid and so obscure. “You could tug forever at the ends of Swift’s elusive, invisible abdominal bundle of avarice and sentiment, art, ego, envy, love and hate, drought and flood, truth and fiction, savior and monster,” Wilson writes, “and it would never come undone.” If that’s not horrifying … —Dan Piepenbring

There once was a time when the scariest thing imaginable was what one never saw: creaks in the floorboard, the rustling of branches against the window, whispers floating in the wind. It used to be that the monsters in horror films were never seen, which got under your skin: think of the spiral staircase of the original The Haunting, the eerie sobs of an unseen woman in The Uninvited, the psychological violence in later films like The Entity. Then slasher flicks and the “video nasties” of the early 1980s came, and we evolved into the terror porn of the Hostel series to laughable films like The Human Centipede. These films are indeed horrific, but are they scary? It’s pretty unlikely that I’ll stumble upon some sadistic German surgeon, but I turn the lights off every night. So it totally makes sense that The Blair Witch Project made millions of dollars—that last image in the basement is still ingrained in my head because—besides being absolutely terrifying—you never know who was behind the terror. (I still can’t go camping without thinking of the film.) One recent film that stands out, and one that gets better with repeated viewings, is The Orphanage (2007). There’s nothing innovative in the storytelling—haunted house, missing child—but it expertly builds the atmosphere of the remote orphanage and the characters who inhabit it. There aren’t as many thrills as something like The Descent—a great example of what is still possible within creature features–but when the scares come they are genuine. The rest is waiting, anticipating, dreading; there’s nothing scarier than what haunts one’s imagination. —Justin Alvarez

A gory horror flick can disquiet even the most courageous moviegoer. But I’m more haunted by 1950s women’s film, a genre that explores female dramas and dreams: romantic entanglements, major wardrobe malfunctions, and domestic crises of all shapes and sizes. Jeanine Basinger (of no relation to Kim), a film scholar and the author of A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women (1993) shares my horror, and investigates this shiny pink brand of cinema, deftly placing our favorite heroines—Bette Davis, Ava Gardner, Jeanne Crain, Jean Arthur, et al—under a microscope. What does a love triangle really signify? Why is the vixen wearing red, and the virgin bedecked in floral? Why does the has-been actress/mother resent her ambitious daughter? With conversational ease and acerbic wit, Basinger reminds us of the many ways that writers in Hayes Code–era Hollywood spoke subliminally, with cues and winks. —Kate Gill

David Foster Wallace’s “Mister Squishy” (from Oblivion, 2004) has mirrors, masks, and poison—three of horror’s tropes, deployed here to clinical, even banal, effect, which makes them all the more terrifying. The story follows a midlevel advertising exec as he conducts a focus group for a new line of superbly chocolatey snack cakes called Felonies!; he’s so fed up with his career, and indeed with the trajectory of his whole life, that he’s elected to turn his focus group into act of terrorism against the advertising industry. His methods, as you’ll see, are the stuff nightmares are made of. And Wallace’s alert, anxious prose taps into our deepest fears about society: about the loneliness, estrangement, and resentment produced by corporate culture; about the way that language, in such a culture, functions as an alienating, dissociative tool rather than a way to communicate; and about the sense that under late capitalism we’re all complicit in a kind of hypnotic consumerism, that we’ll never get out from under “the jargon and mechanisms and gilt rococo with which everyone in the whole huge blind grinding mechanism conspired to convince each other that they could figure out how to give the paying customer what they could prove he could be persuaded to believe he wanted.” —D.P.

I recently rediscovered Lisabeth Zwerger’s selected and illustrated fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen on my bookshelf. It’s a beautiful collection with some of Andersen’s most treasured stories. For me, the most bizarre is “The Tinder-Box” (1835), about a witch with an under lip that hangs down on her breast; three dogs with eyes as large as teacups or windmills or towers; a tinderbox that, with each spark, summons the elephantine-eyed dogs; and a soldier so avaricious it’s chilling. What’s most intriguing is the story’s princess: she’s locked in a tower, as most princesses are, kidnapped and kissed by the nefarious soldier as she sleeps soundly, and when her parents are slaughtered, she sheds not a tear. By the end, fear reigns, the soldier becomes king, and it was all “very pleasing to her.” Now, this could be another display of the vilified damsel. But what if the princess was in on it all? —Caitlin Youngquist

The New Frontier for Art and Commerce, and Other News

Live and create here! Photo: Muhammad Mahdi Karim

If you’re like me, your otherwise successful ghost-hunting expeditions are often thwarted by matters of taxonomy: Was that a wraith you just saw or simply a type-two apparition? Wonder no more. (N. B., the type-two apparition “leaves behind appalling ectoplasm stains on wallpaper and soft furnishings.”)

Today in zingers and put-downs, we bring you Edmund Wilson on H. P. Lovecraft, 1945: “The only real horror in most of these fictions is the horror of bad taste and bad art.”

Whither the artist residency? Say you’re a serious, industrious, diligent artist whose working life requires “solitude, beauty, the natural sublime, and global travel … extended stretches of time, free of any interruption, in order to create new work. All of this can be found on a container ship.” A new residency called Container gives artists the chance to work on just such a ship. (“Artists won’t have to live in a container,” the program hastens to add.)

And while we’re hithering and thithering: Whither Ethan Hawke, who seems finally to have escaped the long shadow of the nineties? “Ethan Hawke was once the mascot we did not ask for. He has become the one we deserve.”

To raise money for Freedom from Torture, seventeen authors—including Margaret Atwood, Julian Barnes, Ken Follett, Hanif Kureishi, Will Self, Alan Hollinghurst, and Zadie Smith—are offering the rights to name characters in their new novels. (They call this an “Immortality Auction,” which implies that all the authors involved expect to have healthy readerships in the coming eons.)

October 30, 2014

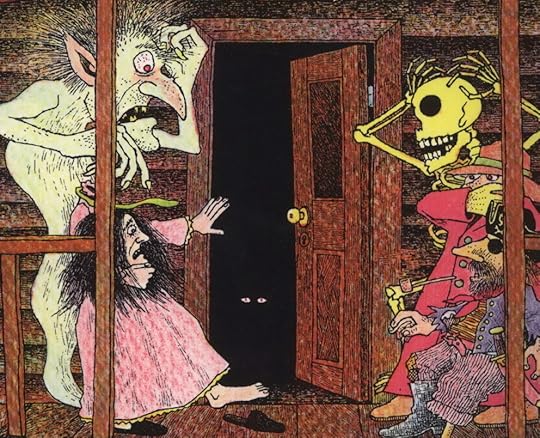

The Not-So-Ghastly Ghosts of Arthur B. Frost

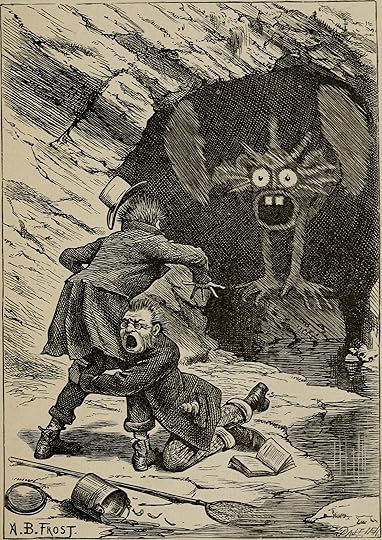

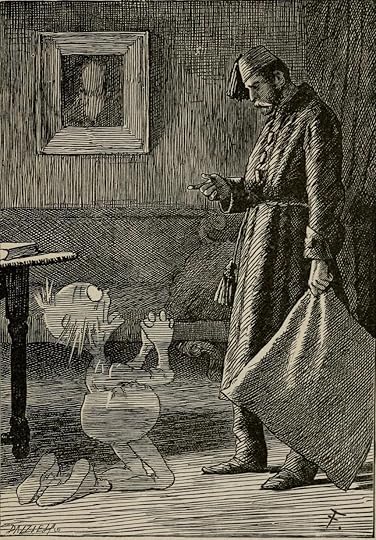

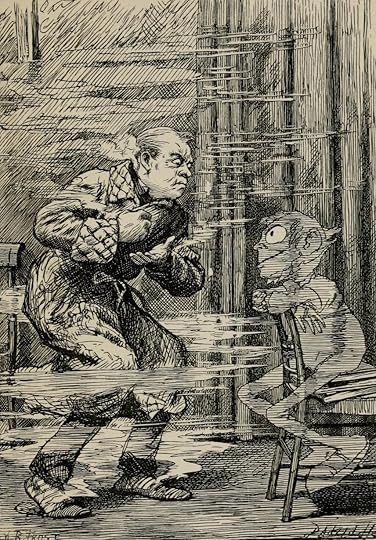

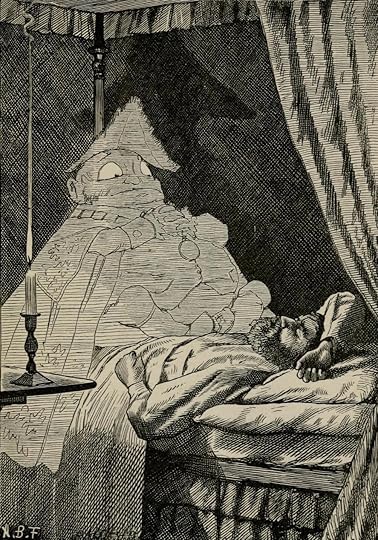

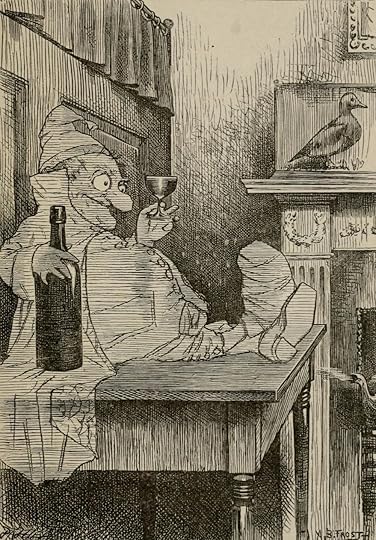

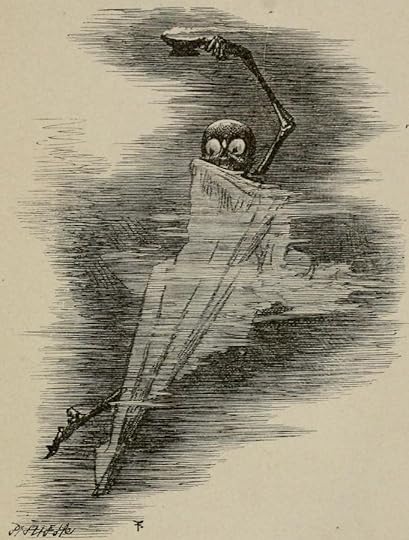

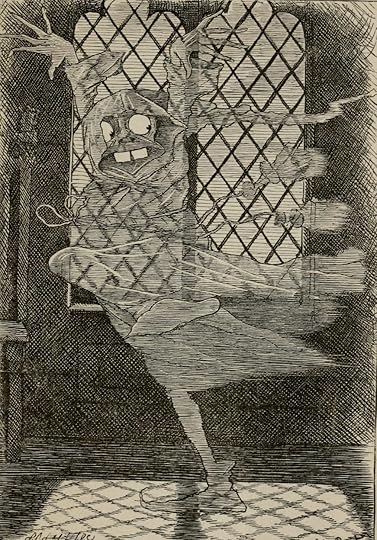

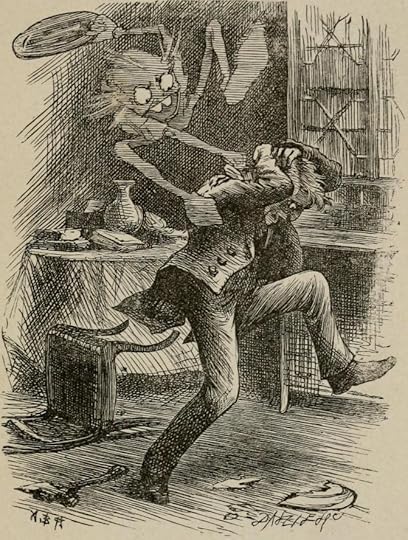

These are a few of Arthur B. Frost’s illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s “Phantasmagoria,” as collected in Rhyme? And Reason? in 1884. Frost was part of the Golden Age of American Illustration; he illustrated more than ninety books, including a few by Carroll.

Satan Comes to Oklahoma City

Facing fears in the Sooner State.

Photo: the Satanic Temple

My ailing wife, Amy, had demanded that I take her to a Black Mass, a well-publicized one that would have meant aligning myself with Satan on local television. These people aren’t really Satanists, Amy explained. They’re blue-collar subculture types who’ve grown up and know their rights and want to thumb their noses at the judgy creeps who persecuted them growing up. Amy, who had seen more than her fair share of those creeps in her own youth, wanted to lend her support.

“Understand that this is all they’ve got,” she told me. “It may seem stupid, but after twenty years of getting shit it’s all they’ve got.”

Despite protests from the local Catholic community, the [Satanic] Church of Ahriman held a Black Mass at the Civic Center in Oklahoma City on September 22. The Catholics had also attempted to file an injunction against them, claiming they had stolen the Holy Sacrament they intended to defile in an unholy consecration. This was their fourth mass, but this time it was for real. The Satanists had won permission to build a monument to Satan on the grounds of the State Capitol, and the wild bad reverend in charge of the Church of Ahriman (also known as the Dakhma of Angra Mainyu) was new and media savvy. He basked in the attention, held interviews and press conferences, did all he could to whip his antagonists into a righteous froth. Those antagonists arrived by the busload and dug in, singing songs and passing out leaflets.

Much of the south refers to itself as the buckle of the Bible belt, but Oklahoma has a special claim to bucklehood: there’s the hard-line Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, and everywhere you turn there seems to be a crucifix; pricey little Amish general stores line the highways and tens of thousands of churches are sprinkled throughout the state, from hippieish splinter sects nestled in the foothills of the Ozarks to goliath megachurches with media teams and television studios and lobbying groups. Life in the Sooner State has a churchy feeling—the stickiness of Kool-Aid soaking through the seams of a waxed paper cup, bake sales manned from behind rickety card tables, devotional sing-alongs, gymnasium lock-ins—and there’s a creeping sense of menace for outsiders.

I’ve experienced a whisper of that menace, living here. A remark I made about the cost of a neighbor’s baked goods led to public denunciations of my work at church meetings and a campaign of vicious online personal attacks. Assigning a Sam Lipsyte story in a college composition class provoked a spectacularly argued series of scripture-laden e-mails from an angry student. For an adult with a professional perch, these are little more than minor inconveniences. But growing up in God’s country is another matter. They want your soul and they’re willing to fight for it.

* * *

My wife, Amy, is from Tampa, Florida, which was definitely God’s country in the 1970s and 1980s. Oklahoma is just like Tampa, she tells me. Nowadays she’s an artist and like me has armored herself with a postgraduate education and a decade and a half of cultural deprogramming in New York City. But in the Tampa of the eighties she was a pale, skinny, redheaded teen runaway, a girl who dressed in black and listened to New Wave and smoked Virginia Slim Menthol 100s and had a look that basically screamed vulnerability—the local Baptist churches slavered to save her soul. She had to push her way past picketing protesters to get to her gyno appointments at Planned Parenthood. Groups of strangers would surround her while she puffed her smokes behind the school bus stop, holding cookies with her name written on them in frosting, and they would pray for her while she smashed them against the pavement, even though she was hungry.

Amy has an invisible illness called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which manifests as a heartbeat that won’t slow down when she changes positions and flurries of excruciating neuropathic pain and clusters of four-day long migraines. Her doctors had been tinkering with her meds, and the present combination sometimes made common words blip out of her mind during conversation. As the day of the Black Mass approached, she was getting worse, speaking to me in an unusual register, frantic and breathless. Her movements reminded me of an animatronic puppet, stiff and strange, with a slouching, lurching gait. In photos taken that week her chin juts out and she looks as imperious and fragile as Benito Mussolini.

“We should get you an appointment with your doctor,” I told her. “This devil-worship stuff is making you nuts.”

The Mass, she said, was all over Facebook, and the fundies were leaving messages, and it was fucking her up but we had to go there. The word triggered has been diluted from overuse, but in Amy’s case it seemed apt: here in Oklahoma, where posters of hacked-up fetuses share floor space with beef-jerky merchants at the state fair, I could believe she was actually being drawn back into her horrible past.

But what had really happened to her? Even after being together for twelve years, I didn’t know. She didn’t like talking about her days as a runaway. When we first met and I was still young enough to be titillated by descriptions of adolescent vandalism, she gave me a recitation that emphasized the cute rebelliousness of it—she belonged to a group of runaways called the Family who lived together in a rancid trailer with no electricity or running water, just a hole and a long drop into the swamp for a toilet. They shoplifted cigarettes and had motel parties where they’d scrawl profanities in Gideon Bibles, and they snuck into camps to steal supplies, and she could field strip a nine-millimeter semiautomatic wearing a blindfold. She’d once set a clubhouse on fire, and when she first ran away from home she’d broken into a church and pelted the altar with paint-soaked tampons.

Then there were her casual mentions of the real reason she’d left home: in her first week of high school, the administration accused her of belonging to an adolescent death cult, and then asked if she was a lesbian, and then conspired to have her committed to a psychiatric hospital. She sometimes spoke of a hyperreligious art teacher who’d hurled her against a wall just before she ran away.

I’d avoided asking her about those days mostly for stupid reasons, as if it would wound my ego if she breathed the name of an ex-boyfriend or I had to hear about how she had to panhandle to pay for an abortion when she was sixteen or about the second abortion at eighteen, when the doctor was so jangled by her sobbing and the chanting and screaming from the protestors outside that he kicked a chair over, and when she flinched at the touch of a cold metal speculum shouted, This is dangerous equipment and if I miss and I gouge you open you will bleed to death here and there is no way in hell an ambulance can reach in time and you’ll die strapped to this table with your knees splayed open. With Satan’s horned head looming over our travel itinerary, I decided that it was time to ask, and this time actually listen to her.

* * *

It was 1987, the beginning of tenth grade for Amy at Chamberlain High School in Tampa, home of the Chiefs, which was a little weird for Amy since her mom was half Cherokee Indian and had passed on her high cheekbones, brittle teeth, and an official Certificate of Indian Blood card, plus some superstitions about the Spanish moss in the trees being dead Indian hair hoisted by spirits; but she didn’t think about it much. Chamberlain was a new school, a dull star-shaped municipal facility made up of low, squat buildings made of concrete and laid out like a prison complex. She was excited because there was an art-class elective, a real art class, with drawing horses and easels and pots of paint and scissors and charcoal. Amy was excited, or she was until she met the teacher.

His name was Mr. Nemeth. Amy scanned him for signs of empathy and intelligence and whiffs of the world beyond Florida. She had a problem with authority figures—especially those who gave her arbitrary time-wasting punishments—but she tried to give them a chance to be human. But this Nemeth gave off nothing. He wore the standard Tampa grown-up guy’s uniform, pressed khaki trousers and a pastel shirt with the sleeves rolled up, but you could tell he was a little off: his nails were grimy and long, and his face was crooked, but it wasn’t a defect, it was just the way he held it, and there was a conspicuous sparkly gold cross dangling around his neck—usually a signal that someone was going to have serious problems with her—and his gaze lingered too long on the girls. And this wasn’t the leer of a food-court perv; it was much more sinister than that. It began as a leer but short-circuited halfway through and became a furious glare, as if his leggy charges had insulted his manhood.

There wasn’t much actual art going on in Nemeth’s class. Half the time he’d hector them about drugs or dating or just rant about whatever Tipper Gore had said about rock music that week. Worse yet he’d only praise the students who were snipping out pictures of saints and cathedral spires and making collages from them around Bible quotations, and would do little more than grunt at Amy and her seatmate Terry. Terry’s work was usually inspired by the band Slayer, though it wasn’t too bad—better than most of class’s. But Amy, who’d been drawing comics since she could crawl, was fairly advanced, and obviously better than anyone else in the class, and she couldn’t stand the idea that this horrible man who called himself an art teacher would gush all over the blousy, cutoff-jeans-wearing, convenient Christians while simply snorting at her.

To pass the time and vent their anger, Amy and Terry would scrawl cartoons on a sheet of notebook paper. They christened Nemeth “Nedemons,” and he became the star of an increasingly grotesque interplanetary adventure. Terry would add tentacles, fangs, and an extra eye to a full-body cartoon of Nedemons, and Amy would raise the ante drawing him dripping with his own filth, the obnoxious cross mutating into a dripping, tumescent phallus. To pass the note, Amy would crumple it up, smile sweetly, and lock eyes with Nemeth, draping her hand over Terry’s desk and letting the crumpled ball fall into Terry’s lap. Of course they got caught.

Nedemons didn’t even pretend to give a damn about Terry—he was a boy, so he was obviously going to dabble in the unholy. But a girl, a girl who shaved her head and wore black and sixteen-hole Doc Martin boots, she needed to be saved. Amy was to become his personal project. She was put upon, as her mother would say. That day after class he pinned her up against the wall and with his face inches from hers ranted about god and devilry and sin, and it happened again the next day and the day following that. Amy started cutting school to get away. The truant officer would haul her back from the mall or Burger King, and Nedemons would be waiting.

These were the days of the Satanic Panic, and so, no doubt with Nemeth pulling strings behind the scenes, things came to a head a few months later when the school called in Amy’s father and prevailed upon him to send her to a mental facility. There was group therapy, there was Narcotics Anonymous, and when she got out, there was Nemeth again, with a group of people singing carols and holding up placards with her name on them.

We don’t ever forget, he told her, so the next time she ran away for good. It was the right decision. Leaving her family was sad, but her family life was imploding anyway—now Amy was finally rid of the Nedemons and the chanting Christians.

In some ways running away doomed her. Without a high-school diploma, she was forced to get a GED—Florida would have kept her from getting a driver’s license otherwise. But a GED wouldn’t get her into college. She tried community college, but she got pregnant a second time and was sick throughout the six months it took to raise the funds for an abortion. She dropped out and worked crappy customer-service jobs—like the one she had at Silk Gardens, a Hobby Lobby clone that reeked of mothballs—and one day, years after she’d run away from home and from school, in walks Nedemons, holding the hand of a prepubescent girl, a scrawny, spindly thing with her hair cut in black bob like Cleopatra who definitely didn’t look related to him. Amy ducked and flattened herself onto the grimy floor until the coast was clear. It was a new low, literally the lowest low, and the moment she resolved to leave Florida.

* * *

The weekend before the Black Mass, the media hype reached its manic peak. Catholic groups rented vans; community churches in Kansas, Texas, Colorado, Arkansas and all over Oklahoma descended on the Civic Center with permission to distribute literature. The Satanists received daily updates from the police department. They were not allowed to come within ten feet of an officer; there was a special segregated parking lot for the mass. Church groups promised to pray for all attendees. There were three bands scheduled to play; two canceled. A flock of reporters came in search of Okie insanity and juicy quotes from yokels on both sides. The bad reverend grabbed as much airtime as he could.

Now I wanted to go. I wanted to write the story and document what happened: I hoped there would be tear gas and flash bangs lighting the sky and protestors clashing. But Amy balked. She was getting sicker. She tried taking fewer pills, but even reducing the dosage by a third brought on a storm of migraines. And an old fear had come back. “We have too much to lose,” she said. “We aren’t going. They’ll hound us forever. I can’t do it.” To her, our lives seemed vulnerable. She knew how relentless the fundamentalists could be. They would be logging license plates, they would have allies in the police force, in the schools—and this wasn’t teenage stuff, this was Satan, this was a fight for people’s souls, a righteous quest against evil and evildoers. They would send letters to employers, picket art shows, summon SWAT teams, call in complaints to HR departments; they were thousands, we were two. Press credentials were no guarantee of neutrality.

So we didn’t go.

On television the news announced that about half of the people who bought tickets showed up. They were tattooed townies, mostly, and they walked in with their shoulders back, as proud as their silly leader. The bad reverend gloated. Somewhere inside the Civic Center a wafer of terrible-tasting biscuit was defiled. Protestors protested. And then the parties climbed into their buses and cars and pulled away and Satan left Oklahoma City.

James McGirk is the author of American Outlaws and an adjunct professor at Northeastern State University and the University of Tulsa, teaching nonfiction writing and composition. Amy McGirk’s artwork can be seen on her tumblr.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers

]

]