The Paris Review's Blog, page 649

October 30, 2014

Ship of Fools

Hieronymus Bosch, The Ship of Fools (detail), ca. 1494-1510, oil on oak panel.

There is something profoundly lonely about sitting in a movie theater, watching something you know to be bad, while people around you enjoy it. I had such an experience recently: the movie had been rhapsodically reviewed, was as full and red a tomato as I’d ever seen on the Internet, had been enthusiastically recommended by people whose tastes I trust. I bought my ticket with high hopes. We want every movie to be fantastic, to change our lives or at least our day. And how rarely we have reason for such hopes! Nevertheless, it was with such an unusually optimistic outlook that I settled into my seat and cracked open my box of Junior Mints.

My first doubts crept in quickly. A joke was cracked; it wasn’t funny. Chill, I told myself. Go with it. It’ll get better. The dialogue was forced and unnatural. Everyone around me was laughing. There’s that moment in a movie when you can’t pretend anymore: when the unassailable realization sets in that, simply put, you’re not in safe hands. Maybe it’s a stupid twist or bad line; more often, it’s just the cumulative stupidity outweighing anything redeeming. You can’t trust the filmmakers anymore, and as a result, you can no longer relax. Besides everything else, it’s exhausting. This movie got worse and worse: clichéd, pretentious, clumsy, vain. I was cringing; the women next to me were laughing heartily. At the end of the movie, much of the audience rose for a spontaneous standing ovation.

It did not occur to me for a moment that I was mistaken. No: they were wrong. The movie was bad. Is this sort of certainty merely arrogance or some sort of madness? Either way, it’s not fun. I’m much too old to derive any satisfaction from poking holes in other people’s pleasure. At $14.50, there are cheaper ways to feel lonely.

* * *

Once, I was riding the subway and this homeless guy got on. I’d seen him before—he rides the same line I do, and he’s hard to miss, at almost seven feet, usually barefoot and dressed in what appears to be a filth-encrusted monk’s cowl. Anyway, it was rush hour, and in the scuffle, maybe my paper grocery bag brushed him. (I don’t think so, but maybe.) The homeless giant turned on me.

“HOW DARE YOU GRAB MY ASS?” he shouted, pointing a menacing finger at me. “DON’T PRETEND YOU DIDN’T DO IT! YOU GRABBED MY ASS! SHE GRABBED MY ASS! EVERYONE, SEE THIS GIRL? SHE GRABBED MY ASS! THAT’S SEXUAL HARASSMENT! IF IT WERE THE OTHER WAY AROUND, I’D BE ARRESTED, BUT SHE’S JUST ALLOWED TO GO AROUND GRABBING MY ASS?”

It did not end there. It went on for at least ten minutes—we were on an express—which is like two hours in rush-hour time. No one really knew where to look. I was beet red. I kept my eyes down while he yelled at me. Did I defend myself? Deny it? No, better to ignore the whole thing. After all, maybe it was good that he had the self-respect to think someone might fancy him enough to sexually harass him, when the truth was, everyone on the train was giving him as wide a berth as was humanly possible. One thing was certain: whatever the truth, he was very sure that I had grabbed his ass.

In Madness and Civilization, Foucault writes that,

Confined on the ship, from which there is no escape, the madman is delivered to the river with its thousand arms, the sea with its thousand roads, to that great uncertainty external to everything. He is a prisoner in the midst of what is the freest, the openest of routes: bound fast at the infinite crossroads. He is the Passenger par excellence: that is, the prisoner of the passage. And the land he will come to is unknown—as is, once he disembarks, the land from which he comes. He has his truth and his homeland only in that fruitless expanse between two countries that cannot belong to him.

Here is what I can tell you: that movie was terrible. And we all need our truths, no?

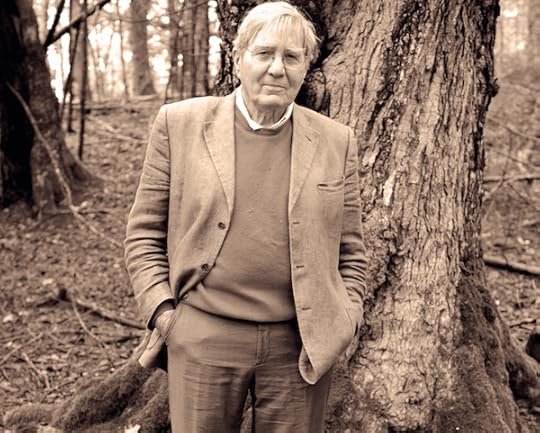

Galway Kinnell, 1927–2014

Photo via GalwayKinnell.com

Galway Kinnell, who aspired to a poetics that “could be understood without a graduate degree,” died on Tuesday in Vermont, at eighty-seven. A winner of both the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, Kinnell wrote poems that “dwell on the ugly as fully, as far and as long as I could stomach it,” as he once told the Los Angeles Times. “I think if you are ever going to find any kind of truth to poetry it has to be based on all of experience rather than on a narrow segment of cheerful events.”

Tony Hoagland said that Kinnell’s primary subjects were “mortality, erotic love, and creatureness.” That might make him sound solemn, But Kinnell, who was born in Rhode Island, could also be exceptionally warm, especially when his subject was New England. An obituary by the Associated Press quotes Major Jackson, who included Kinnell among “the great quintessential poets of his generation”:

In my mind he comes behind that other great New England poet Robert Frost in his ability to write about, not only the landscape of New England, but also its people … Without any great effort it was almost as if the people and the land were one and he acknowledged what I like to call a romantic consciousness.

It would be hard to overstate the effect of Kinnell’s poems on the form at large. “I don’t think Galway Kinnell influenced me, but what’s more important, he inspired me,” Philip Levine said in his Art of Poetry interview:

When I read his great poem “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World,” I said, My God, this is how good the poetry of my generation can be. I can remember exactly where I was when I first read it, on the second floor of the library in an armchair holding The Hudson Review and shivering with excitement.

The Review published Kinnell’s poems throughout his career; his work first appeared in our Spring 1965 issue. We’ve made available one of those earlier poems, “On the Frozen Field,” which begins:

We walk across the snow,

The stars can be faint,

The moon can be eating itself out,

There can be meteors flaring to death on earth,

The Northern Lights can bloom and seethe

And be tearing themselves apart all night,

We walk arm in arm, and we are happy.

You can also read “The Geese,” from our Summer 1985 issue, and “Lackawanna,” from Fall 1994. But best of all is “Another Night in the Ruins,” which Kinnell read at a Review salon in 2001; you can hear the recording here.

All’s Welles That Ends Welles, and Other News

They’re doing what? Orson Welles in 1960.

“Whatever type styles were available to The Paris Review founders at the time of printing had just been embraced without our modern preoccupations of ‘branding’ and ‘identity.’ It was less a carelessness than a carefree-ness. At first the uptight twenty-first-century graphic designer in me was frustrated by this inconsistency, but I came to rather admire the early Reviewians for maintaining a consistent voice while continuing to see themselves anew with each issue.” An interview with our art editor, Charlotte Strick.

“American Sign Language isn’t a translation of English. It’s a language with its own grammar and idioms. Sign language speakers also have their own accents … There are also variations in sign language speed. New Yorkers are notorious fast-talkers, while Ohioans are calm and relaxed. New Yorkers also curse more.” (We’re foul-mouthed, even with our hands.)

When did the chapter emerge as one of the most essential tools in book-length writing and storytelling? “The chapter has become a way of looking at the world, a way of dividing time and, therefore, of dividing experience. Its origins date back to long before the printing press or even the bound codex, back to the emergence of prose in antiquity as both an expressive and an informational medium. Literary evolution rarely seems slower than it does in the case of the chapter.”

After Evelyn Waugh married for the second time, he received a letter from a woman he’d known as a student at Oxford: “I think of you all the time when I am making love, until the word and Evelyn are almost synonymous! And in the darkness each night & in the greyness of each morning when I wake I remember your face—& your voice and your body and everything about you so earnestly and intensely that you become almost tangibly beside me.”

Orson Welles’s unfinished final film, The Other Side of the Wind, may finally see release next year for the centenary of his birth. “The main character’s life has echoes in Hemingway’s: his father’s suicide, the day of his death, his love of Spain … Welles explores the last day of the fictional director’s life before he dies in a car crash that could be an accident or a suicide.”

October 29, 2014

Who the Fuck Was That Guy?

From the first-edition jacket of Henry Green’s Party Going.

I’m delighted to hear from Bob that you have undertaken an interview with Henry Green. I meant to write you last spring that I had tea with him in London—with his wife, some others, and Christopher Logue, that frenetic poet whom you may remember from Paris and who worships Green and begged to be taken along. Well, he was, and there was Green in a double-breasted black business suit going under the name York (sic), talking like a businessman from Manchester, with an anecdote or two, terribly long—one, as I remember, about a seal two old ladies found on a beach near Brighton and nursed back to health in their bathtub, the point of the story being that in England alone could such a thing happen. Logue kept darting looks at the door, for Green, I guess, and making side remarks of incredible rudeness to York. When we left, Logue asked: “Jesus, who the fuck was that guy on the sofa.” “Henry Green,” I said.

—George Plimpton, from a letter to Terry Southern, 1957

Ever since I read that letter (plug: it’s from our Fall issue) I’ve had Henry Green’s seal anecdote on my mind, mostly in light of the many questions it raises: How did those old ladies transport the seal? What was entailed, exactly, in nursing it back to health, and how did they know it was well again? Did they keep it as a pet afterward?

I fear the answers are lost to the ages.

As Plimpton tells it, Green wasn’t very stimulating company, but—given what I know of his persona, and the intense affinity I feel for his seal story—I can think of few writers I’d rather spend an afternoon with. I envision us puttering around his family’s pipe factory in Birmingham, perhaps checking various gauges, with Green in his business suit, his hands clasped behind his back, carrying on a kind of tour-de-force monologue all the while, losing his place and opening several series of parentheses with no intention of closing them. Listening to Green hold forth, I imagine, was probably a lot like reading him: an enlightening, exhilarating, and not infrequently exhausting experience.

In October 1963, just before his fifty-eighth birthday, Green contributed a brief piece to The Spectator: “For Jenny with Affection from Henry Green.” (I’d never encountered it before today. Don’t ask me who Jenny is; she’s never mentioned again.) By this time he hadn’t put out a book in more than a decade, and he seems to riff on this silence; he writes mainly about the hows and whys of being a hermit:

Green lives with his wife in Belgravia. He has now become a hermit. Only the other day a woman of sixty looking after the tobacconist’s shop was dragged by her hair across the counter and stabbed twice in the neck. That is one reason why I don’t go out any more …

Love your wife, love your cat and stay perfectly quiet, if possible not to leave the house. Because on the street if you are sixty danger threatens.

It has always been said as a sign of age that if you don’t see policemen with medal ribbons it means that you are getting very old. In other words, the policemen are very much younger. One of the reasons I won't go out is for fear of meeting a policeman. Yesterday I saw four at the corner and was very frightened indeed.

… So the whole thing is really not to go out if one can afford it, the best thing is to stay in one place, which might be bed. Not sex, for sleep.

It’s all this way, maddeningly, wonderfully elliptical, at once less and more profound than it’s supposed to be—a prime example of what Updike saw as Green’s “air of peddling nothing and knowing everything.” There’s that one perfectly tortured construction (“It has always been said as a sign of age … that you are getting very old”) that strikes me as the essence of what you might call Green Logic, a limber, sleepy-eyed cousin of the logic you learn in school. And what are we to make of that swap in the first few sentences from the third person to the first, offered without notice or reason? It’s just like that seal story: more questions than answers. The whole piece is here; it won’t be the most essential thing you read today, but it will have … an effect. A definite effect.

“Most of us walk crabwise to meals and everything else,” Green had said in his Art of Fiction interview a few years earlier. “The oblique approach in middle age is the safest thing. The unusual at this period is to get anywhere at all—God damn!”

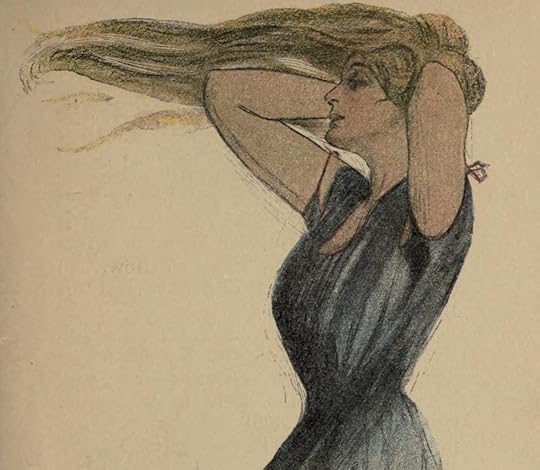

Raised on Promises

An illustration from Cupid’s Cyclopedia, 1910.

If you’re looking for a crash course in prewar hilarity—or, indeed, in American gender dynamics—get yourself to the nearest used bookstore and pick up a copy of 1910’s Cupid’s Cyclopedia, “Compiled for Daniel Cupid by Oliver Herford and John Cecil Clay.” Perhaps the infantile title and winking byline give a sense of the work’s witty tone.

Clay was a popular commercial artist of his day. Herford, meanwhile, was a successful professional wit; he was actually known as the American Oscar Wilde. (One imagines those who called him that had never read much Oscar Wilde.) He wrote a good bit of doggerel, plus such urbane texts as The Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom for 1903, The Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom for 1904, The Entirely New Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom for 1905, The Complete Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom for 1906, The Altogether New Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom for 1907, The Quite New Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom for 1908, The Perfectly Good Cynic’s Calendar, The Complete Cynic, and The Revived Cynic’s Calendar (1917).

As to the Cupid’s Cyclopedia, it was not just for cynics. On the contrary! It’s a pretty book, embellished with mischievous pen-and-ink cupids and liberally illustrated with watercolor plates. Here’s the author’s note:

It has long been the belief of the authors that Love-making should be included in the regular curriculum of our schools. It seems to us the most important branch of co-education.

How few of us know how to make love properly, and how very few, after making it, know how to keep it!

So much depends upon the kind of love that is made. There are no artificial methods for preserving love, but the best kind will keep forever. Few beginners know how to make the lasting kind, and many, even, of those with vast experience, keep at it.

We hope that this book will fill a long-felt want. Surely of all long-felt wants the want of love seems longest.

It is for the earnest student of True Love that we have inspired this cyclopedia.

What follows is an alphabetized list of vaguely love-related words with cutesy captions. (“Bill: See Coo.” “Husband, n.: See Brute.”) There are also maps and charts detailing the behavior of the typical American girl and beau—and then there are those illustrations. These, you see, identify the various types of American girl. Rather like a protohipster handbook, Cupid’s Cyclopedia attempts a full taxonomy of femininity. But it should be said that all of them—from “The Typist” to “The Western Type” to “The Bathing Girl” (“They can hardly be called aquatic, as they hardly go into the water enough to more than wet the feet”)—have a uniform, Gibson Girl look, with dramatic S-curves, sharp pen-and-ink snips of noses and clouds of improbable pompadour.

And don’t worry, the wit doesn’t stop here! We learn that “Type A Widow, Found the World Over” is “Very Dangerous to Man.” And as to the “Type Found Pretty Much All Over North America”?

NOTE THE HEAD-DRESS OR WAR-BONNET OF FEATHERS. THEY HAVE ALSO VARIOUS COLORED SUBSTANCES KNOWN AS “WAR-PAINT,” WHICH THEY SMEAR ON THEIR FACES, GIVING A GHASTLY AND UNNATURAL APPEARANCE. THIS PRACTICE IS QUITE COMMON. SOME OF THIS TYPE, HOWEVER, ARE MOST ATTRACTIVE, ESPECIALLY THOSE FOUND IN THE UN-UNITED STATES.

It’s no stupider, really, than half the novelty gift books on the market today. Hackery is eternal. But I still don’t understand the intended audience: even if these guys were considered the most hilarious thing going and people snapped up their work unquestioningly, this book seems too tame to tempt even the most milquetoast of young bucks; might young women have chortled over its naughtiness? Someone must have: shortly thereafter, the duo reteamed to pen Cupid’s Fair-Weather Booke. Second verse, one presumes, same as the first. But then, I’m a cynic.

Future Eligibles

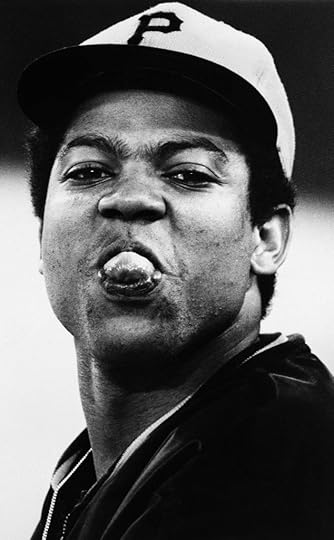

Finding a Hall of Fame for Dock Ellis.

Dock Ellis getting a manicure in a Detroit barbershop on July 13, 1971. He was starting pitcher later that day for the National League in the All-Star Game with the American League.

Let’s get Dock Ellis into the Hall of Fame. Oh, not really, of course—by the Hall’s statistical criteria, he isn’t even close. But after a visit to Cooperstown in September, I found myself imagining a Hall of Fame that would enshrine him.

Ellis is unquestionably famous, after all—infamous, too. He is the subject of No No: A Dockumentary, which headlined the Hall of Fame Film Festival I attended last month; a Society for American Baseball Research panel event a few weeks later; a psychedelic song, recorded in 1993, by Barbara Manning; and, especially, an excellent book, published in 1976, by The Paris Review’s own Donald Hall, Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball. Evidence keeps mounting that Dock—always flamboyant, often controversial—was the emblematic player of his era, the seventies, with its dubious introduction of such artificialities as the designated hitter and Astroturf; the acrimonious battle for free agency; and all those drugs.

Ah, yes, drugs. Ellis, who died in 2008, is best known as the pitcher who, in 1970, threw a no-hitter while tripping on acid—appropriately, his name in a box score reads, “Ellis, D.”—but that freak feat is a red herring, and it’s not even his most freakish. On May 1, 1974, Dock decided to send a message to the Pirates’ archrivals, the intimidating Cincinnati Reds, who had cowed Pittsburgh into competitive docility. “We gonna get down,” Dock decided. “We gonna do the do. I’m going to hit these motherfuckers.” Donald Hall recounts Ellis’s plan and its execution. The first guy Dock hit was Pete Rose (who should also be in the Hall of Fame, though for very different and far more genuine reasons). After he hit three batters, walked another who ducked and dodged four pitches, and threw two beanballs at future Hall of Famer Johnny Bench, Ellis was mercifully removed from the game with this remarkable stat line: zero innings pitched, no hits, no strikes thrown, three hit batsmen, one walk, one run allowed. “Dock Ellis faced four batters in the first inning,” the box score decorously explains. Dock’s own explanation of himself in No No says more: “It’s not that you’ve got to watch how I pitch,” he insists. “You’ve got to watch how I play.”

The Hall of Fame is as much a fortress as a cathedral, and in some places it protects numbers more than heroes. An entire floor is devoted to the former—61, 3,000, and so on—and one baseball sabermetrician has even designed an earnest and elaborate data-crunching system to compute the Hall-worthiness of each candidate. Every off-season, baseball experts squabble over the nominees like pets over food, and make a dog’s breakfast of it.

It’s silly, and it misses the point, especially in this case. Ellis was the spiritual heir to Jackie Robinson, each a key symbol of baseball blackness for his time. In No No, Ellis shares a letter of support he received from the retired Robinson in 1971, when Dock was having the best season of his career. Robinson wrote him after Ellis made combative comments to the media, claiming he’d never be named the National League starter for the All-Star Game. Vida Blue had already gotten the American League nod, and “they wouldn’t pitch two brothers against each other,” Ellis declared. He was a master button-pusher. He was charismatic and sported flashy clothes and cars; wore curlers in his hair while in uniform, until management ordered them removed; and brazenly nominated himself as a book subject for Donald Hall, who was hanging around spring training looking for something to write about. “He was a chapter ahead,” says his Pittsburgh teammate Bruce Kison, in No No, and Kison wasn’t talking about Hall’s book. Ellis got that starting spot in the All-Star Game.

“I want you to know how much I appreciate your courage and honesty,” Dock reads aloud from Robinson’s letter of praise, offscreen. The torch is being passed, the era changing, from civil rights to Black Power to blaxploitation, Sidney Poitier to Richard Pryor. In 1971, the Pirates fielded baseball’s first all-black lineup, with Dock on the mound; they went on to win the World Series. As Dock reads the letter, his voice grows more intense, then wobbles, and then, on Robinson’s words “Try not to be left alone,” erupts into sobs. “Aw, man!” he wails in a teary falsetto. “I never read that like that!”

I was at the film festival representing Ivan Weiss’s Bull City Summer making-of film, Leaving Traces. I’d tell people our documentary was about the Bulls, and their eyes lit up every time. When the Bulls call themselves America’s favorite minor-league team, they aren’t exaggerating. One memorabilia store’s window boasting MINOR-LEAGUE GEAR FOR SALE displayed an enormous blue-and-orange Bulls logo, the iconic bull crashing through a Stonehenge-size D and virtually right onto a Cooperstown street.

Why is the Hall of Fame here, anyway, in the land of Natty Bumppo? Because of a myth: Abner Doubleday did not invent baseball in Cooperstown. “Every year,” Bernard-Henri Lévy writes in American Vertigo, “millions of men and women come, like me, to visit a town devoted entirely to the celebration of a myth.” Nonetheless, there is the Hall of Fame myth that Doubleday inspired, as well as Doubleday Field, right in the middle of town. On Friday afternoon before the film festival, there was a game going on. An over-forty league from Baltimore had rented out the park. Potbellied and hip-replaced men chuffed as they rounded bases and muffed easy grounders, but something remarkable came over them as the setting sun cast golden light from beyond right field: Put a baseball uniform on almost any man, no matter his age, shape, or arthritis, and he looks like a ballplayer. His carriage changes; his face, too. He walks with stoic uprightness, acquires a frontiersman’s sense of gravitas that can explode into urgent, heroic daring at any moment. When a third baseman named Andy Shank (a great baseball name) speared a line drive, reaching for it backhanded, the play had the same snap and fling as its major-league iteration. The game is the game, no matter who plays it, and it’s great.

* * *

Despite its portentous reputation, the Hall of Fame is surprisingly small (you can see the whole thing in two or three hours), not because it’s inadequate, but because baseball is so big. The Hall only has room for the greatest hits, and it manages to gather nearly all of them, along with a lot of memorabilia, which provide a fascinating evolutionary history. Balls used to have tiny, low stitches, which must have vexed pitchers (smooth balls don’t move as much in flight), jerseys were wool cardigans, and bats were cumbersome and imbalanced. Gloves were maddeningly slow to change. The one Willie Mays used to make “the catch” in 1954 looks unthinkably tiny. So does the great second baseman Joe Morgan’s. (Morgan also took one in the ribs from Dock that day in Cincinnati.) How did he ever catch anything in it? He had to have his glove hand in exactly the right place to snare that little white rat as it scurried toward the outfield. Morgan’s glove sits there in its shrine, stronger evidence of his greatness than any of his numbers.

The tools of the trade are the most interesting things in the Hall (the hallowed plaques are the least). Look at 2014 inductee Tom Glavine’s shoes: the left one has the ankle cut away, exposing the inner foam core, in order to give relief to his injured Achilles tendon. The gorgeous satin jersey on the second floor, worn briefly by the Braves when they started playing night games in 1946, was not an aesthetic or comfort choice but “for better visibility under artificial lighting.” I started to think more about what belongs in the Hall of Fame, less about who—not least because the Hall is a private nonprofit, founded by a hotelier in an effort to boost tourism during the Depression, and although it is MLB approved, it isn’t an unassailable authority. The Hall farms out its induction votes to a motley group of baseball writers, some of whom barely qualify as such, and the committees that round up players whose eligibility has expired have made many poor decisions. Highpockets Kelly is a great name, and so is Lloyd “Little Poison” Waner, but neither belongs in the Hall, not even by its own reckoning; clubbiness, perception, and pedigree trumped even the numbers in these cases and others. Still, the Hall does manage to snag nearly all the deserving in the end, and it makes those it refuses even more famous: Pete Rose, Shoeless Joe, Barry Bonds. To the right of the plaques for the 2014 inductees hang a clutch of empty ones, awaiting future honorees. It’s nearly impossible not to see them as the plaques that rightly belong to Bonds, Roger Clemens, and all the other greats whose performance-enhancing drug use has kept them out.

Who would have pegged LSD for a performance-enhancing drug? It was one for Dock that day in 1970. It’s not to say he would have been a Hall of Famer had he dropped acid before every start, of course. He’d probably have been out of baseball well before his actual exit in 1979. But he was halfway out of baseball even in uniform, and not just because his mind was usually altered. “If Dock is pitching,” one of his teammates marveled, “you know he’s high. But how high is he?” And on what? In Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball, Hall takes him out to lunch in Cincinnati at Pigall’s (they refused Dock entrance until he went back to his hotel and put on a coat), where Dock ate poached trout and knocked back plenty of Pouilly Fuissé—“his favorite wine,” Hall notes—“moaning with the excellence of the food.” Pouilly Fuissé!

Dock Ellis, 1971.

Since Dock’s time, ballplayers have lost most of their color, and their combativeness is restricted almost exclusively to the diamond—they have one of America’s most powerful sports unions and little to fight for anymore when it comes to money and labor rights. They no longer participate much in the culture around their sport, which is itself shrinking. Two of the eleven entries in the Hall of Fame Film Festival were about saving old ballparks, two were about baseball teaching young people intercultural appreciation and understanding, and two were about the Chicago Cubs. We were also treated to twenty just-discovered seconds, at full speed and then in slo-mo, of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig playing an exhibition game in Fresno in 1927. It was like watching footage of a couple of ivory-billed woodpeckers.

As I walked through the Hall’s gallery of plaques, I overheard a kid ask his grandfather, Where’s Derek Jeter? Grandpa: He’s not in yet. (Active players aren’t eligible.) As Jeter’s career came to its prenostalgized end in September, the striking thing was his participation in his own early induction. He accepted feting and gifts in every big-league ballpark on his farewell tour—including what seemed like innumerable ceremonies in his Yankee Stadium home—wore custom cleats that looked suspiciously like Hall of Fame plaques, and did a Gatorade commercial so self-aggrandizing and condescending (and in black-and-white, of course) as to verge on parody. If Ellis was the heir of Jackie Robinson, Jeter is the heir of Joe DiMaggio: the classical ballplayer, rightly beloved by the masses and his peers, amazingly graceful and strong on the field even as his skills declined with age, his play full of personality and audacity and heroics; yet characterless and dry off the field, where he was necessarily chary of the media, some of whom didn’t shy from taking resentful parting shots even as others piled on the mound of hagiography. The polarization has only made Jeter more famous, of course, but his inarguable greatness was plainly visible to us right on the field. Dock Ellis’s ran far beyond the country of baseball. They both belong in some kind of Cooperstown.

Adam Sobsey has covered the Durham Bulls since 2009 and was the lead writer for the Bull City Summer documentary project in 2013. He has also written for Baseball Prospectus since 2011. He is at work on a book about Triple-A baseball. Follow him on Twitter.

Inhabiting the Invisible Plane, and Other News

A monotype print by Grady Gordon. Image via Beautiful Decay

“My mind is so dumb when I write. Each story requires a different style of stupidity ... I don't know how the mind works, but isn't there a part of it that deals specifically with reason and sense? The brainy asshole of the mind? ... That asshole is my intellect. He's a really shitty writer, as you might imagine.” Lorin Stein interviews Ottessa Moshfegh.

Librarians versus algorithms: Who recommends better books? The latest developments in a John Henry story.

A new exhibition at Tate Britain shows paintings alongside William Hazlitt’s criticism about them, reminding us of what a vital, unusually perceptive critic he was. “One purrs at what he’d have made of the homogenized, commercialized art world of today—and how surgically he might have cut into it.”

Sven Birkerts in (and on) convalescence: “How the feel of time changes when all the terms are altered. What on most days had moved with an almost hectic momentum, an ill-choreographed succession of one thing after another, one day just halted, causing the hours to then pool up behind it: the afternoon immobilized, with almost nothing to mark the change or confirm that this is not the world paralyzed into still life.”

Grady Gordon makes monotype prints “by removing thick black ink from a plexiglass surface.” They’re ghoulish. They “bring about the characters that inhabit the invisible plane.” They make great gifts for your enemies.

October 28, 2014

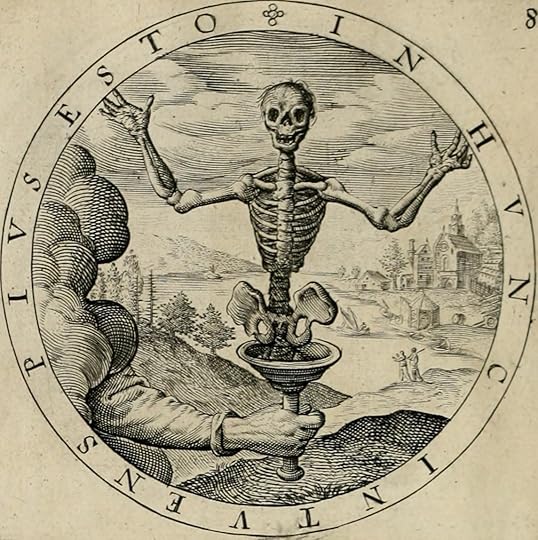

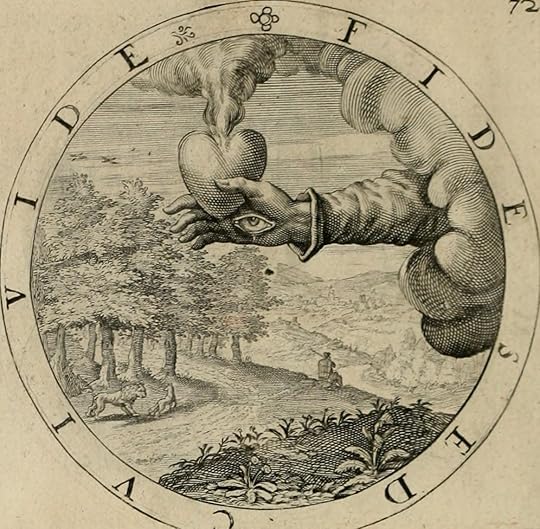

Moral and Divine (and Terrifying)

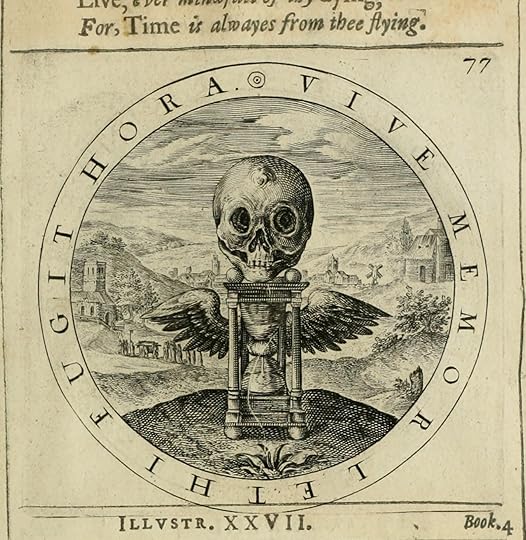

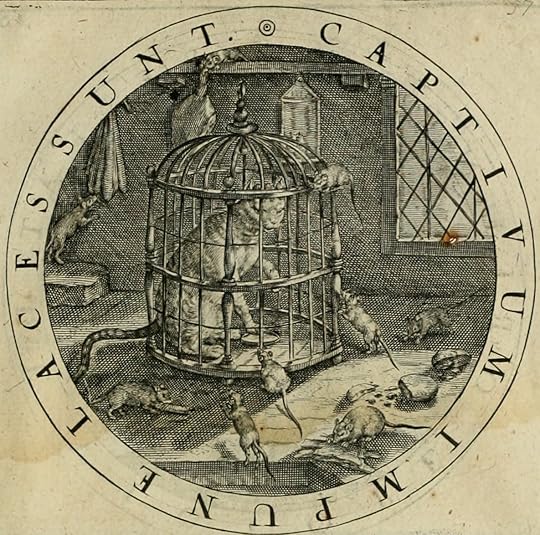

Cruel fate.

Yesterday’s journey into the macabre (via Thackeray) was so lousy with skulls and black cats and seasonal pageantry that I thought, Hell, let’s do it again.

The public domain is teeming with hoary, scary fare for Halloween. Time was, you couldn’t throw a rock without hitting something spooky.

I present to you, then, a few morbid selections from George Wither’s A Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne: Quickened with Metrical Illustrations, both Moral and Divine; and disposed into Lotteries, that Instruction and Good Counsel, may be furthered by an Honest and Pleasant Recreation, from 1635. Wither wrote verses to accompany these allegorical plates, which were originally by Crispin van Passe from earlier in the seventeenth century. The allegories depicted here aren’t always easy to parse, but I think we can safely assume that they instruct humankind in the evasion of sin. If you sin, after all, your hand may wind up mounted to a stick, or you may become like the caged cat, beset by the mice you once terrorized.

Political Theater

The Death of Klinghoffer and grand opera’s political tradition.

The Death of Klinghoffer. Photo: Metropolitan Opera

Opera is the most pretentious art form of all time, which makes it an easy target for the Marx Brothers and for Bugs Bunny—but its pretension makes it explosive. And—surprise—even in the wake of the death of City Opera and the Met’s labor disputes, it is explosive in America, where a revival of an American opera about the death of an American against the backdrop of international geopolitics has become a scandal or a sensation, depending on who you talk to. (Whether it’s selling tickets, only Peter Gelb can tell us.)

No recent film or album or musical has caused the kind of agony that John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer has; outside the Met, hundreds of protesters have accused it of anti-Semitism. Its reception makes any real appraisal of its virtues or weaknesses impossible—the same fate that befell, say, Parsifal, Birth of a Nation, Guernica, and Cradle Will Rock, in their times.

Why has Klinghoffer faced such intense hostility? An English friend recently said to me, with enormous authority and disdain, You have no tradition of political theater in America. That statement is absurd, but the following is true: England has Shakespeare’s histories, continental Europe has opera, and America has … Shakespeare’s histories and Europe’s operas. I should note that I ran this by an extremely knowledgeable friend last night, who was distraught at this simplification; We did have a tradition, he said, And it was systematically eradicated and watered down by McCarthyism, and many of us have worked very, very hard to bring it back! He’s right, of course. That said, we do not have an ongoing, unbroken, native, above-ground tradition of accepted political theater. We have musicals, yes, but the musical has never had the direct connection to political power and patronage that the London stage, the Paris Opera, and Bayreuth do. And so we tend to be both overawed by and suspicious of these forms. They have a special status, but their political content is not ours.

Since it’s not ours, we may not understand how inextricably bound the art and the politics are. Carl Dahlhaus’s magisterial book Nineteenth-Century Music turns the usual narrative of classical music—its inevitable march toward atonality and modernism—on its head. Music, he says, was an instrument and an expression of political power, inextricably bound up in economic, class, and religious transformations, and above all in the rise of nationalism. In his panorama, chamber music, the symphony, and solo music fall away, leaving a century of choral music, operetta, and, at the dead center, opera.

And opera, grand opera, featured a parade of violent religious wars, exiled slaves, and nationalist hysteria. Operas were both an engine and a critique of imperialism. Think of Verdi and his first big hit, Nabucco, with its chorus of Hebrew exiles—“Va, pensiero”—that became the de facto anthem of Italian nationalism; or Aida, with its Nubian slave love and her father’s desire for armed revolt against their oppressors; or even Macbeth, which gained a chorus of Scottish exiles lamenting their occupied land. Think of Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots, in which bloodthirsty Catholic priests sing a grotesque travesty of a hymn as they plan the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre; or Auber’s La Muette de Portici, whose story of Italians under Austrian occupation supposedly caused the Belgian revolution. Even innocent Rossini wrote William Tell, about the conflict of love and honor in Austrian-occupied Switzerland. Think of Mendelssohn’s two oratorios, one Christian and one Jewish, as if to identify the religious confusion of his own family of converts. Think of Wagner.

The form’s origins are in the reforms of Gluck (radical simplification, clarity of diction), the breakthrough of Mozart (who wrote music that was esoteric yet popular, and created a stylized world filled with people who seem alive), and the massive festival cantatas of the French Revolution and the rediscovery of Bach’s passions. With this came the transformation of opera from an exclusively aristocratic form with stories from the ancient world to a bourgeois and even populist one, with stories about everyday people and modern (or, at least, early modern) historical and political events; thus the scandal of operas like La Traviata—ripped, as it were, from the headlines. Verdi had originally set the opera in the present day, but censors made him change that. Over and over, these works present fictionalized people in real historical contexts, trapped in the machinery of actual geopolitics. This naturalism was new and shocking.

It still is. Amazingly, Klinghoffer has all the same nineteenth-century tropes: the choruses of exiles; the eclectic score, sometimes exotic and sometimes pastiche; the nationalist and religious hysteria; the apparent conflict between bourgeois tragedy and historical imperatives; and the debate about the ethics of blending documentary and fiction. Its defenders will cite the gorgeous choral writing, the inventive use of Adams’s trademark orchestral minimalism to provide momentum and continuity, the frequently beautiful arias, and the even tone of the strange libretto, which refuses to clarify its politics. Its detractors will cite the libretto’s refusal to clarify its politics, a few oddly inserted arias, and the fact that the piece plays more like an oratorio than an opera.

The work coolly refuses to take sides, which may seem admirable, and Adams himself has said that the piece is modeled on Bach’s Passions. But imagine the “St. Matthew Passion” untethered from piety. For that matter, imagine Nabucco without the clear sympathy for the Jewish exiles, or Parsifal without Parsifal. Which may be to say that what’s missing is—dare I say?—vulgarity.

Beyond the obvious parallels with Bach, and between the choruses of Palestinian and Jewish exiles and “Va, pensiero,” another opera lurks in the background here, also on the subject of the question of Zion: Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron. (And look! Even in this forbidding score, Schoenberg makes a concession to showbiz vulgarity with a sexy ballet.) Schoenberg’s feelings about Israel were clear, but he’s unable, in the opera, to reconcile the conflict between faith and government, or one could say between music and the word, represented by the two brothers. At least in his case, the reason is clear: he never finished act three of his magnum opus.

Grand opera is, and has been, at war with itself: populist but aristocratic, revolutionary but reactionary, imperialist but critical of imperialism. These are total, inviolable, integrated artworks that are also showbiz whores—they’ll do anything for a good curtain. And the music! Banal, sublime, bombastic, exotic, phantasmagoric, with folk songs and hymns, historic pastiches and the music of the future. This is a form arguably defined by its lack of integrity: Why is an opera not just a play or just music? Why all this melodrama? Why the tacky sets and sexy dances? And why the audiences who are so upset but who can seldom be bothered to actually watch?

Michael Friedman is a composer and lyricist in New York City.

Palpable Disappointment

Or, the hazards of wearing a Paris Review shirt.

Vintage Paris Review advertisement.

While I was shopping for milk, I felt a hand tap my shoulder. It was a lady of perhaps sixty, wearing arty jewelry. “Excuse me,” she said. “I was just wondering … are you from … Paris?” She said the last word with an exaggerated French accent: Par-ee.

I stared at her blankly for a moment. She, in turn, was staring at my breasts. I looked down and realized that I was wearing a Paris Review T-shirt, the dark blue 2013 version that’s modeled on a design from early in the magazine’s life. THE PARIS REVIEW, it says, along with an image of the hadada ibis in its Frisian bonnet.

“Oh, no,” I said apologetically. “No. I’m from here.”

This is not, of course, an uncommon error; as names go, The Paris Review—which denotes a magazine based in New York, one that publishes zero reviews—is among the most misleading out there. I can’t think of another title that’s quite so dishonest. To paraphrase Mary McMarthy’s remark about Lillian Hellman, every word here is a lie, including The. (Okay, maybe not The.)

I was prepared to explain that the American founders had indeed started the magazine in Paris in 1953; that they’d moved to New York in 1973; that upon George Plimpton’s death they’d relocated operations from his Seventy-second Street apartment to an office. I was not going to say—but was thinking—that in any case, in my experience, Parisians don’t tend to advertise their Parisian-ness on their clothing. Or maybe they do; as I’ve stated, I’m not one.

As is so often the case, the clarification resulted in palpable disappointment.

“Oh,” said the woman. “I was going to ask you about baguettes.” She indicated the bakery section.

“You can!” I said. “I think I’ve tried all the breads here, and some are way better than others.”

“No,” she said. “That’s okay. Thanks.” And she walked away.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers