The Paris Review's Blog, page 647

November 5, 2014

Poetry Brothels, and Other News

Gerard van Honthorst, De koppelaarster (The Matchmaker), 1625.

A new English-language interview with Knausgaard: “I once met a German journalist who compared me to a rock band. He said, the books don’t really have any focus, it’s just loose, it’s like just having some songs about drinking and they don’t have anything else. But it’s in that band photo, that image, where everything comes together. He wondered if I had a certain point in my writing, because it’s all, you know, bits and pieces and nothing. And then he saw pictures of me, he said, ‘You pose like a rock star, you kind of summarize everything there’ … He meant it really, really badly.”

Today in the anxiety of influence: the aftereffects of one writer’s childhood obsession with Michael Crichton. “Much of the rhythm and timbre I claimed as my own in fact belonged to Crichton: isolating revelatory sentences on a line break between paragraphs … complex sentences interspersed with short sentence fragments like the dots and dashes in Morse Code. Even in my early twenties, writing bad pseudo-autobiographical short stories, it seems that I had retained, by osmosis, the stylistic habits I’d developed while eating ham-and-cheese sandwiches, drinking Coke, and imagining my name writ large on the shelves of an airport bookstore.”

Just when you’d been thinking, Hey, it’s been a while since I heard a quality new acoustic musical instrument, along comes the Yaybahar, recently invented in Turkey; it uses “a combination of two drum-like membranes, long springs, and a tall fretted neck” to produce plaintive, resonant sounds.

Must we continue to live in a world where this is happening? “She wears a leather corset and harem pants, like a gypsy girl from a fairytale. She is barefoot. In the dim candlelight, she asks what I’m in the mood for—something sexy? Something dark? I tell her what will please me, and she reads me a poem. She calls herself a poetry whore, and I have paid for her company. For the next ten minutes or so, she will read me her verses, converse with me, entertain me.”

Fun facts about mace: it was invented in Pittsburgh in 1964 by a couple who kept an alligator in the basement. “At first they called it TGASI, for ‘Tear Gas Aerosol Spray Instrument,’ but soon they came up with the catchier name of ‘Chemical Mace’ … the name implied that chemicals could produce the same incapacitating effect as a medieval mace—a chilling design of spiked club—but without causing the same brutal injuries.”

November 4, 2014

Congressional Districting in Iowa

It’s late, and you’re still awake. Allow us to help with Sleep Aid, a series devoted to curing insomnia with the dullest, most soporific prose available in the public domain. Tonight’s prescription: “Congressional Districting in Iowa,” a paper from the July 1903 issue of the Iowa Journal of History and Politics.

From Tacuina sanitatis, fourteenth century.

It is the purpose of this paper to outline briefly the history of legislation on the subject of congressional districting in Iowa—pointing out the changes made from time to time, showing by means of maps the exact form and extent of the districts established by the several acts of the General Assembly, and commenting upon the motives and circumstances prompting alterations in the boundaries of these districts. Prior to 1847 there were no congressional districts in the State. From 1838 to 1846 Iowa existed as a separate Territory, entitled to one Delegate in Congress, who was chosen for a term of two years and who represented the entire territorial area and population. Then came the change incident to statehood. On August 4, 1846, Congress passed an act defining the boundaries of the State of Iowa and providing that, until the next census and apportionment, the new State should be entitled to two seats in the House of Representatives. A State Constitution was adopted, and on December 28, 1846, Iowa entered the Union. The State had not, however, been districted in time for the election of that year; hence the two congressmen were chosen on a general ticket, each to represent the State as a whole. Since that time Iowa congressmen have been elected by districts and the General Assembly has enacted seven laws respecting the division of the State for this purpose.

THE ACT OF 1847

On December 7, 1846, the State Senate voted that a “select committee of seven” be appointed to “report a bill to the Senate, dividing the State into two congressional districts, so as to include, as nearly as can be done, an equal portion of the territory and an equal portion of the population of the State in each district, and that the vote given in August last for and against the constitution be taken as the basis in dividing the population.” This committee reported a bill which was later referred to a selected committee of three from each judicial district. From this body the bill emerged in a somewhat modified form; and, after considerable discussion and amendment both in the Senate and in the House, it became a law, February 22, 1847. This first statute on the subject divided the State into two congressional districts: the first was to consist of the counties of Lee, Van Buren, Jefferson, Wapello, Davis, Appanoose, Henry, Mahaska, Monroe, Marion, Jasper, Polk, Keokuk, and the country south of a line drawn from the northwest corner of Polk county west to the Missouri river; the second was composed of the counties of Clayton, Dubuque, Delaware, Jackson, Clinton, Jones, Linn, Poweshiek, Benton, Iowa, Johnson, Cedar, Scott, Muscatine, Washington, Louisa, Des Moines, and all north of a line from the northwest corner of Polk county west to the Missouri. From the standpoint of area, of population, and of politics, this arrangement seems to have been equitable. Turning to Map I, on which the limits of the two districts are indicated, we see that the dividing line marks off a southern, or first district, and a northern, or second district, which are fairly regular in outline, but quite unequal in area. This inequality is, however, readily explained in this way. To compensate for the sparse settlement of the northwest, the eastern portion of the boundary line veers to the south so that the comparatively dense population of the southeast may be shared by the second district. In population, on the other hand, the first (and smaller) district leads by more than 2,000; while in voters it outnumbers the second district by about 500. As to politics, each district returned a Democratic majority of a few hundred. But there is little ground for a charge of gerrymander; for, while the Whig minority was large in each case, it was so distributed as to make the formation of even one Whig district impossible, except through the establishment of the most irregular and unnatural boundaries.

THE ACT OF 1848

Early in January, 1848, a bill was introduced into the House of Representatives providing for the transfer of Poweshiek county from the second congressional district to the first. Apparently without opposition, this measure passed both houses, and on January 24 received the signature of the Governor. Why this transfer was made, is not clear. It is true that on this same January 24 the first law was passed for the organization of the county of Poweshiek, whose boundaries had been fixed a few years before; but this change in the status of the county did not necessitate a change in its relation to the congressional districting of the State. The transfer was not to equalize the population of the two districts; for the census returns for 1847, 1848, and 1849 show that the inhabitants of the first district outnumbered those of the second by several thousand. Nor could the political motive have been weighty; for, while the election returns indicate a decreasing Democratic majority in the first district and an increasing Democratic majority in the second, the Whig majority of five in Poweshiek was not sufficient to make any material difference in the political complexion of either district. The chief merit of the law seems to have been that it tended to straighten the dividing line and so make the form of the districts more regular.

THE ACT OF 1857

On January 24, 1857, Mr. Foster from the Senate committee on apportionment reported a bill to alter the boundaries of the congressional districts. The measure promptly passed both houses without amendment, and on January 28 became a law. By its terms, three counties (Des Moines, Louisa, and Washington) were detached from the second district and attached to the first. The reasons for this change are not far to seek. In the first place, the population of the second district had been increasing much more rapidly than that of the first. In 1849 the latter had numbered 86,899 inhabitants, while the former had only 68,074; but in 1856 the order of precedence was reversed, since the first district had but 222,120, whereas the population of the second had grown to 285,755. A slight change of boundaries was, therefore, warranted in order to restore equality. Moreover, several circumstances argued in favor of the transfer of the three counties mentioned in the act. It tended to equalize the population of the two districts, and yet guarded against the necessity of a too early readjustment, by giving the first district a slight excess of inhabitants to offset the more rapid increase in the second. Furthermore, it served to secure greater regularity in the boundaries and forms of the districts than any other arrangement would have done. But it seems also to have subserved partisan ends. In the congressional election of 1856 the second district returned a Republican majority of 6,017, while the first went Republican by only 955 votes. The second was safe; but no great change of sentiment would be requisite to give the first to the Democrats. The counties of Des Moines, Louisa, and Washington alone had, in 1856, given a majority of 862 for the Republican candidate. This vote could be shifted to the first district; and so, without endangering party success in the northern district, the Republican chances in case of general Democratic gains would be strengthened several fold. The outcome of the election of 1858 vindicated the wisdom of this precautionary step; for the Republican majorities were reduced to 2,739 in the second district and 600 in the first, while the three counties in question were carried by only 499 votes. This last number subtracted from the 600 would have left the dominant party with the uncomfortably narrow margin of 101 in the southern district. The act of 1857 had relieved the Republicans of great anxiety and fortified their success for the future.

Still awake? Read more here.

Gertie Turns One Hundred

A century ago, well before Jurassic Park or The Land Before Time or even plain old moribund Godzilla, cinema’s preeminent dinosaur was Gertie, a colorless, potentially narcoleptic herbivore, species indeterminate, fond of dancing and casting elephants into the sea. Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) was one of the first animated films; it pioneered key-frame animation, a technique in which a story’s major positions were drawn first and the intervening frames were filled in afterward. Gertie’s creator, the cartoonist Winsor McCay, made more than ten thousand drawings of her, and these, as you can see above, yielded fewer than seven minutes of animated footage. (If you want to skip straight to the Gertie goods, head to the seven-minute mark, but beware—you’ll miss some riveting live-action scenes featuring well-dressed gentlemen shaking hands, well-dressed gentlemen gathering at a dinner party, and well-dressed gentlemen smoking.)

This Friday, as part of the MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation, the animation historian John Canemaker hosts a screening of Gertie and three of McCay’s other early animations, “as well as a re-creation—with audience participation—of the legendary routine that introduced Gertie in McCay’s vaudeville act.” No elephants will be harmed.

William Carlos Williams’s “Election Day”

An abandoned grade school in La Prairie Center, Illinois, used as a polling place in 1973. Photo: National Archive

Your typical polling center seldom evokes the poetic. In my neighborhood, we’re assigned a local elementary school. There are student projects lining the walls: family trees, doggerel, pictures. (“Children only!” a volunteer yelled at me when I tried to use the girls’ room—which, fair enough. But everyone in the place was over eighteen.)

Enter William Carlos Williams. His “Election Day,” from 1941, is spare and sardonic; vote before reading.

Warm sun, quiet air

an old man sits

in the doorway of

a broken house—

boards for windows

plaster falling

from between the stones

and strokes the head

of a spotted dog

A Penny Saved Is a Waste of Time

How our coins got their names.

The 1909 penny.

Election Day is here again, and I know there are some single-issue voters out there who haven’t forgotten an issue of our time that Congress has repeatedly failed to act on, despite the introduction of bills HR 3761 in 1989, HR 2528 in 2001, and HR 5818 in 2006. President Obama has stated that he is in favor—the lobbyists for outnumber the lobbyists against—and yet the Price Rounding Act, the Legal Tender Modernization Act, and the Currency Overhaul for an Industrious Nation (COIN) Act, respectively, have all failed to pass. As a nation, we have yet to abolish the penny.

A penny costs more to produce than it is worth (even after the 1982 change from a 95 percent copper composition to 97.5 percent zinc), so the U.S. loses tens of millions of dollars a year minting them; the sheer cost of lost time spent hunting for pennies, waiting in line behind someone else hunting for pennies, and disposing of pointless pennies once we have them has been estimated at as high as a billion dollars a year. No coin in U.S. history has ever been worth less than a penny is today, by a long shot: the half cent, eliminated in 1857, was worth more than a dime in today’s buying power. A penny saved may be a penny earned, but it is about two seconds of income for an average American, so who cares. Yet again, the Ben Franklin for our time turns out to be Andy Warhol: “I hate PENNIES. I wish they’d stop making them altogether. I would never save them. I don’t have the time. I like to say in stores, ‘Oh forget it, keep those pennies. It makes my French wallet too heavy.’ ”

One thing we’ll lose, when the penny eventually goes the inevitable way of the half cent and the Canadian penny (extinct as of 2012), is the last possible link between our language of money and the everyday physical world.

A quarter is a fourth of a dollar, a dime a tenth (Old French dîme, Latin decima), a cent a hundredth or one percent—all math. Anyway, a cent is not a piece of money: a U.S. penny is technically a cent or one-cent coin, but in spoken language, a cent is a value and a penny is a coin. We offer someone our two cents, not two pennies; pennies can clink in your pocket, cents can’t. (When Americans adopted the British term penny in 1793, they took over the distinction, too: in England between pennies and pence.)

Nickel refers to something specific, but also tautological and unreal. A nickel is made out of nickel, the little devil, a diminutive Old Nick: a Nickel in German is a goblin or rascal, and nickel ore was called Kupfernickel, or devil’s copper, mischievously tricking miners and yielding no copper despite its coppery appearance. (The German etymology is why nickel ends in -el, not -le, like another German import, pumpernickel.)

As for penny, its etymology is uncertain, though the ending implies a Germanic origin—the word used to be penning, with an -ing, like shilling and farthing, instead of a -y. The root may be Pfand, which turned into the English word pawn meaning “a pledge or token”: in that case, penny basically just means money. Or it may derive from the German Pfanne, “pan,” the round metal thing that you cook in. My head says it’s pawn: the pan pun sounds like classic folk etymology that somebody simply made up. But my heart belongs to Pfanne: surely the original coin goes back to some concrete reality, an object of actual use.

What about dollars? They have a definite birthday, January 15, 1520, when Bohemia’s Counts von Schlick began minting coins from silver mined in St. Joachim’s Dale: Joachimsthal (now known as Jáchymov, Czech Republic, near Karlovy Vary). These coins were called Joachimsthaler, soon shortened to thaler. (The H is silent, the vowels pronounced just as they are in dollar.)

Dollars also have a brother of sorts, a demon far worse than the tricky Nickel: pitchblende. (Pitch refers to its black color; blende is another kind of ore, from the German blenden, deceive, because the material was dense enough to be metal but had no known economic uses. Those German miners were fooled again.) It was pitchblende, now called uraninite, from Joachimsthal, in which Marie Skłodowska-Curie discovered and isolated radium, leading to her Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911 and her death from radiation exposure in 1934, five years after a certain golemically named Dr Löwy of Prague had shown that “mysterious emanations” in the mine led to cancer. (Miners: 0 for 3.) Until World War I, the birthplace of the dollar was the only known source of radium in the world. Get rid of the penny and, maybe it’s only fair, self-referential fractions and nuclear poison will be all we have left for the meaning of money.

Damion Searls, the Daily’s language columnist, is a translator from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch.

Walt Whitman, “Election Day, November, 1884”

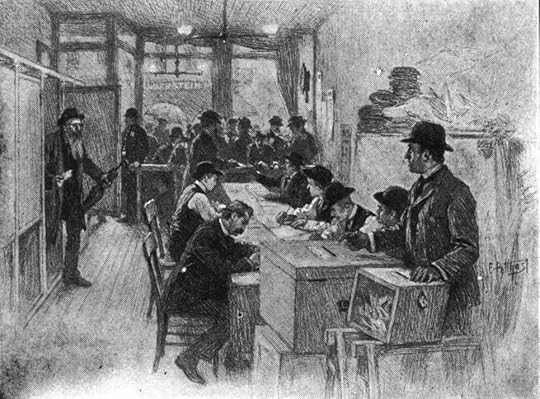

A polling place in New York ca. 1900.

A reminder: Walt Whitman really, really liked Election Day. Nothing could quicken the man’s pulse like a good showing at the polls.

As “Election Day, November, 1884” has it, he preferred the spectacle of democracy—the “ballot-shower from East to West”—to any of our nation’s natural wonders, including, but not limited to, Niagara Falls, the Mississippi River, Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Great Lakes … you name it, Whitman thought the vote was better than it. (You’d think someone could’ve sold him on the Rockies, at least.) One can imagine a latter-day Whitman passing up a trip to the Grand Canyon and instead hunkering down at the TV, flipping anxiously from network to network as the precincts begin to report, wringing his hands. Not, mind you, that he would have any particular stake in the outcome; he’d just be along for the great democratic ride, clucking his tongue at the gerrymanderers of the world.

(If you need an antidote for all this unalloyed patriotism, try Charles Bernstein’s “On Election Day,” which contains, among many excellent lines, “The air is putrid, red, interpolating, quixotic, torpid, vulnerable, on election day.” I know which poet would get my vote.)

If I should need to name, O Western World, your powerfulest

scene and show,

’Twould not be you, Niagara—nor you, ye limitless prairies—nor

your huge rifts of canyons, Colorado,

Nor you, Yosemite—nor Yellowstone, with all its spasmic geyser-

loops ascending to the skies, appearing and disappearing,

Nor Oregon’s white cones—nor Huron’s belt of mighty lakes—

nor Mississippi’s stream:

—This seething hemisphere’s humanity, as now, I’d name— the

still small voice vibrating—America’s choosing day,

(The heart of it not in the chosen—the act itself the main, the

quadriennial choosing,)

The stretch of North and South arous’d—sea-board and inland

—Texas to Maine—the Prairie States—Vermont, Virginia,

California,

The final ballot-shower from East to West—the paradox and con-

flict,

The countless snow-flakes falling—(a swordless conflict,

Yet more than all Rome’s wars of old, or modern Napoleon’s:)

the peaceful choice of all,

Or good or ill humanity—welcoming the darker odds, the dross:

—Foams and ferments the wine? it serves to purify—while the

heart pants, life glows:

These stormy gusts and winds waft precious ships,

Swell’d Washington’s, Jefferson’s, Lincoln’s sails.

November 3, 2014

The Poet Bandit

Black Bart, the outlaw poet.

November 3, 1883, marked the beginning of the end for Charles Earl Bowles, aka C. E. Bolton, aka Black Bart the Poet, aka the very picture of delinquent suavity. Bowles was a legendary nineteenth-century stagecoach robber known for the poetry he left at the scenes of his heists. Over the course of nearly a decade, he pulled off some two-dozen robberies hither and yon, concentrating on Wells Fargo stages throughout Oregon and Northern California. He made off with thousands of dollars a year plus the many intangibles that come with being a criminal mastermind, and he never once fired his gun or rode a horse.

Many fragments of his poetry survive, but apparently only two verses can claim Bowles as their author with full certainty. (Understandably, the guy had a lot of copycats.) Both of these merit close exegesis. The first was found at the scene of an August 1877 stagecoach holdup:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor, and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tread,

You fine-haired sons of bitches.

And the second verse, found at the site of Bowles’s July 25, 1878, holdup:

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will, I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse;

And if there’s money in that box

‘Tis munny in my purse.

Bowles had a pretty good reputation, as far as highwaymen go. People referred to him as a gentleman bandit, a man of sophistication. A police report described him: “A person of great endurance. Exhibited genuine wit under most trying circumstances, and was extremely proper and polite in behavior. Eschews profanity.”

Of course, that report wouldn’t exist had Black Bart not run into trouble that fateful November 3, when he held up a stage in Calaveras County, en route to Milton from Sonora. The exact location, I shit you not, was Funk Hill, just southeast of Copperopolis.

Alas, all did not go well on Funk Hill. At the ferry crossing where the stickup went down, Black Bart took heavy fire from two Wells Fargo fellas named (I’m still not making this up) Reason McConnell and Jimmy Rolleri. One of the bullets hit him in the hand; he used a kerchief to stop the bleeding, but he left it at the scene. Rookie mistake, Bart! Wells Fargo detectives traced it, with considerable effort, to a laundry in San Francisco, where they learned that Bowles lived in a boarding house nearby. He was toast: six years in San Quentin Prison.

Being a gentleman, though, Bowles was out in four—his sentence was commuted for good behavior. As the story goes, he was mobbed with reporters upon his release, and they asked him, as reporters are wont to do, if he planned on resuming his career as a criminal. Quoth Wikipedia:

“No, gentlemen,” he replied, smiling. “I’m through with crime.” Another reporter asked if he would write more poetry. Bowles laughed and said, “Now, didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”

In Which André Malraux Kills Death

An engraving by Fernand Léger.

André Malraux was born today in 1901, and his first novel, Paper Moons (Lunes en papier), was published when he was only twenty. If that provokes pangs of jealousy, bear in mind that the print run was limited to 112 copies. The National Library of the Netherlands has a terrific post about the first edition, which was published by Éditions de la Galerie Simon, one of the most forward-thinking publishers of its day.

As that small print-run indicates, Simon wasn’t a major operation. Malraux’s publisher, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, had a shrewd and prescient eye for writers and artists. He was also an art dealer, one of the first to find merit in the work of the Cubists, who were largely written off as pretentious pranksters at the time. As a publisher, he sought work that “accomplished in words what the Cubists did with paint”; accordingly, he published early work by Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Raymond Radiguet, Pierre Reverdy, and Antonin Artaud, among others, often with artwork from his friends. In the case of Lunes en papier he called on Fernand Léger to contribute several wood engravings. This was not, it must be said, a popular or canny decision at the time:

Léger [had] caused a sensation at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911 with his Nude in the Woods (Nus dans la forêt). Kahnweiler was immediately intrigued and attempted to contact its creator, who had previously made a living as a draughtsman for an architectural firm. Léger was mockingly called “tubiste” because of his tube-like presentations: he felt isolated and unappreciated.

As for the novel itself:

Lunes en papier continually subverts the reader’s expectations, starting with the cryptic subtitle and the warning in the front of the book: “There is nothing symbolical in this book.” The three stories are absurdist in nature, with strange plot turns and metaphors, airy, sometimes humorous in tone, while still dealing with seemingly serious matters, and ending with the death of Death … Malraux would later qualify his first effort as a “gloire de café.” But it suited the Surrealist and Dadaist ideas of its time extremely well.

There’s a translated excerpt from Cipher Journal that includes the bit where Death dies. More specifically, Death—a woman in a dinner jacket that makes her look like an insect—receives a visit from a dubious physician, who informs her that she may be going bald. He prepares her a bath of nitric acid. She slides on in and begins to corrode; by the time her servant intervenes, it’s too late, and Death has resigned herself to dying.

“Dear friend, I’ve had enough. The world (it’s useless to stand there gaping—I’ll soon be dead) the world is only tolerable to us because of our habit of tolerating it. They inflict this tolerance on us when we’re still too young to resist, and then … do you see what I mean? If we can suppress the habit of—”

“I don’t understand … ”

“Well, it’s not hard to figure out! Let’s say your friends are eggcups, for example. Can’t you see them handing out, at random, the title of God of the Eggcups, and confiding to him their eggcup desires? Can’t you imagine the female eggcups saying with a smirk ‘The balance and harmony of the female eggcup is clearly superior to that of the male eggcup’? My god, just look at them all! I’ve had enough of the whole game, I tell you, enough! I’m ill and you’re trying to pick a fight with me—well I’m taking my umbrella and leaving. My departure will be a great practical joke. They call me Death but you know perfectly well that I’m only Chance. Slow decay is just one of my disguises. But, now, where’s she gone? Rifloire! Rilfoire! She took off! The slut! Whore! Well … finally! I’ve been a torment to her, and now that I’m going to die she won’t be able to even take revenge upon me. Oh, let’s get it over with!”

And she lit a cigarette. A sinuosity of smoke rose like a delicate, wispy girl floating on the air, and Death tried to imagine all sorts of pornographic shapes, tried to will them into movements that would correspond to the swaying of the thread of smoke.

And not a single cushion stirred.

Danke Schoen

A still from The Entertainer, 2005.

If I need to, I can date my periods of depression by the corresponding enthusiasms for terrible TV shows. Enthusiasms is maybe the wrong word: let’s say commitment to.

Now, at the best of times, I can be sucked into watching almost any show—give me a marathon and I’m yours for the next twenty episodes, and I genuinely mourn the passing of Most Eligible Dallas—but when I think of the other times, the bad times, my devotion had a different quality: resigned, enervated, yet obsessive. It was sort of coaxing a tepid crush out of boredom; with a little care and a lot of time, you can create something that approximates a genuine interest.

And I was willing to put in the time. There was my relatively respectable Upstairs Downstairs fixation after I moved into my parents’ house after college, when I’d spend my days crouching by the mail slot, waiting for the red Netflix envelopes to arrive with my fix. Even now, I see those weeks in 1970s BBC yellow. Less defensible was the obsession with the Australian soap McLeod’s Daughters, which could only be watched (a) during the day and (b) on Lifetime. This one crept up on me. Did I enter a McLeod’s Daughters contest to try to win a trip to the outback? Maybe. Let’s just say that when the booby prize, a faux-silver cowboy-boot key chain, arrived in the mail, it felt like a wake-up call.

But by any measure, the nadir came in the summer of 2005. I know the date because it was the one and only season of Wayne Newton’s The Entertainer, which aired on E!. Wayne Newton’s The Entertainer was part of the spate of copycat programs that followed the early success of American Idol, and the talent-show premise was similar. Ah, but here was the twist: The Entertainer was not restricted to singers—it sought to give exposure to all kinds of Vegas-style razzle-dazzle. As such The Entertainer was composed not merely of singers, but of ventriloquists, magicians—sorry, “illusionists”—and comedians, too, all vying for the grand prize: opening for “Mr. Vegas” himself. (Apparently Wayne Newton is called that, though I’m not sure by whom.)

In the grand tradition of such programs, the contestants—each of whom was given a nickname like The Showstopper, The Sexy Diva, The Magic Man, or The Ice Queen—also lived in close proximity to one another. There was some low-grade flirtation between an aspiring singer (The Country Girl) and The Joker, a prop-comic. One guy, I think he did impressions, halfheartedly tried to mess with people’s heads. There was always some kind of challenge: putting on a lounge act, throwing together a wedding, working as a team to mount a full-scale show. (I distinctly remember a manic and disorganized rendition of “Celebration” from the finale of that one.) Wayne Newton—looking like a walnut-stained baby-doll in a Roy Orbison wig—presided over everything. He’d often impart wisdom—“the lounge show is the soul of Las Vegas”—and when someone was on the chopping block, he’d imperiously demand, “Entertain me!” At which point the contestant had a chance to win a reprieve, as from an arbitrary monarch.

The show was premised on Wayne Newton’s status as a showbiz legend; by dint of contractual obligation, madness, or brainwashing, all the contestants seemed to subscribe to the view that Newton was an unquestionable luminary. Their awe when they saw his house—Casa de Shenandoah, with its “seven-hundred-year-old piano”—was matched only by their enthusiasm for the macabre rendition of “Danke Schoen” he croaked out in episode three.

One arc concerned the two-episode rise and fall of a human beatbox (nom de guerre: The Wild One) who was initially perceived as the one to watch. But then he had some kind of vague existential crisis, swigged cheap vodka from a plastic handle, and let his team down in the wedding challenge. Wayne Newton’s wrath in this case was swift and terrible to behold. “Mr. Newton,” began the Wild One. “I respect you more than any man I have ever met—”

“That’s enough!” thundered Newton. “You are not the Entertainer!”

In the end, The Showstopper won. I see he has a MySpace and is singing on cruise ships now.

But that’s not the point. I didn’t care who won. The show drew me in partly through nostalgia—in this case, for the old Vegas, the one now subsumed by Celine and her troupes of sinister dancers. And as with any fourth-rate reality program, the cravenness of it was of course a draw. Most of all, perhaps, I needed the painless dose of responsibility. If American Idol made people feel involved in a great enterprise, I liked the sense that I was the only person in the world bothering to tune in to The Entertainer. It felt like an obligation, a trust, even. And maybe I wasn’t so wrong to feel burdened; Wayne Newton has since filed for bankruptcy, and Casa de Shenandoah is currently on the market.

A Conversation About Our Secret Life in the Movies

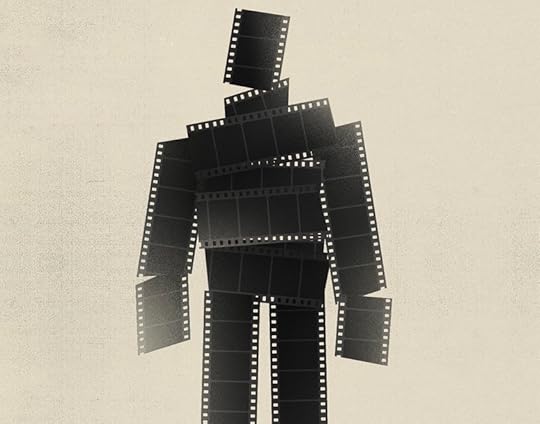

A detail from the cover of Our Secret Life in the Movies.

When the writers Michael McGriff and J. M. Tyree lived together in San Francisco, they set out to watch every film in the Criterion Collection. Their new book, Our Secret Life in the Movies, is a coauthored mash note to cinema classics from Andrei Tarkovsky to Michael Mann: a novel in fragments, vacillating between fiction and autobiography, with more than thirty pairs of stories inspired by the films they watched together. Part collage and part homage, Secret Life follows two boys as they come of age in Reagan-era America, where the video store is the locus of the imagination and the fear of a nuclear winter looms large in the collective conscious.

McGriff and Tyree sat down together to discuss their impetus for the project, the enigma of writing about moving images, and their influences in literature and film alike.

J. M. Tyree: I’m trying to remember how we got the idea for Our Secret Life in the Movies.

Michael McGriff: We were roommates in San Francisco, both teaching in the Creative Writing Program at Stanford, and I somehow convinced you that it would be a good idea to watch the entire Criterion Collection that year.

JMT: We were living in that wonderful place near Mission Dolores, a block away from where Alfred Hitchcock created the fictional grave of Carlotta Valdes in Vertigo. The Criterion project was a real Y-chromosome thing, wasn’t it? We were watching two or three movies a day, eating a lot of pizza, drinking a lot of sambuca. I think our book evolved naturally from the feeling that movies and life seep together out there in the fog.

MM: We started writing these pairs of stories. For each movie that fascinated us, we’d both write one story. A double take on the film. We decided to leave our names off the individual stories and let the book have a life all its own.

JMT: Then the stories started connecting and linking up and merging and growing and taking over—cue The Blob. Why did you want to write a book about movies?

MM: I’ve always gone to film as my primary source of inspiration. Tarkovsky and Bergman taught me how to be a poet just as much as reading Tranströmer and Neruda.

JMT: Your poems often invoke images of growing up in the rainy mud of rural Oregon, but they do feel intensely cinematic to me.

MM: For whatever reason, telling stories one frame—one image—at a time feels like the purest form of art making to me. There’s something alchemical about watching great movies. I’ll never forget going down to the local movie rental place as a family and buying a brand-new top-loading VCR. I remember my dad hoisting that huge box into the back of his pickup.

JMT: It’s amazing how horrible the images look now on VHS, but also how you can feel and hear the gears and tape moving and touching. It’s tangible and charming. That’s the sound of the eighties, isn’t it? The sound of our childhoods. The movies entered our dreams early on. They entered the home.

MM: Alongside Reagan and the Space Shuttle Challenger and The Day After.

JMT: Like Faulkner said in his Nobel Prize address, we were all waiting to be blown up. By the Russians or by ourselves or by computer error, like in WarGames. Our Secret Life tries to capture the feeling of that era. Did you dream about nuclear war?

MM: All the time. Most of Our Secret Life deals with aspects of growing up during the end of the Cold War. It’s amazing how many references there are to Soviet-era Russia, and how Cold War rhetoric defined American life in the eighties. Finishing the book with a homage to Tarkovsky, whose own work had to get past Soviet censorship, seems totally apt. And we talk a lot about nuclear annihilation, which Tarkovsky directly and indirectly addresses in many of his films. And his masterpiece, Mirror, shares the logic of our book—that strange, metafictional yo-yo of a film that bounces between points of view, linear and nonlinear time, characters who bleed in and out of each other’s consciousnesses.

JMT: That idea of something that reads like autobiography even though it is clearly fiction. We tried to design this book so it could be read from cover to cover like a fragmented novel—and the reader wouldn’t need to know the movies to read the book. Sometimes the connections between the stories and the movies are very loose, just an outlandish What If? provoked by a single image. We wanted something more associative and evocative, less literal-minded …

MM: Right—something that had the life and motion of a book with narrative arc and tension, not merely a compilation. For months we tried various arrangements, swapping, deleting, and adding stories. We finally ordered the pairs in chronological order, with the early sketches embodying the characters’ childhoods and stories that touch on World War II and Vietnam, and with later sketches moving toward the characters’ adulthoods and the attacks of 9/11. The book suddenly popped to life after we organized it chronologically. Richard Brautigan is an obvious influence on the book. He came up in our conversations. His novel In Watermelon Sugar gets a shout-out in one of our stories. We definitely share an affinity for Brautigan’s vignette-style prose. Did you have him in mind while you were writing?

JMT: I did. I appreciate his brevity and his weirdness. He knew how to take himself not so seriously. The fact that he was both experimental and playful. He seemed to be having fun, at least in his books, but there was also this horrible sadness underlying his work.

MM: As readers, we both gravitate toward—though I hate the word—experimental prose.

JMT: There was a golden age of that stuff, wasn’t there? In the early seventies, Doris Lessing would publish her new sci-fi novel, The Memoirs of a Survivor, and then claim it was her attempt to write an autobiography. What a genius! Barthelme, Burroughs, Ballard. I miss all that loose, meandering, try-anything weirdness. There’s still this idea of the short story that’s twenty pages or more, a format originally designed to fit print magazines in the twenties. I think art should try to keep pace with—to colonize—new technologies. I’m seeing the page now more as a screen or a Web page, an online space that elicits the reader’s attention—as I’ve heard it described—in a different way. I don’t mind at all if someone reads my work on a phone or a tablet. I like the idea of cell-phone fiction, designed to bring cheer to odd moments on the bus or in the waiting room, to fill up all those in-between times and to reclaim dead spaces.

MM: I don’t share your enthusiasm at all. What a horrible thought. John Berger said that art has been reduced to screens. “The days of pilgrimage are over.” What I’m more interested in is the collision of the narrative world and the world of images—art anchored by some kind of narrative tension. What was your most recent mind-bending movie-watching experience?

JMT: I’ve been watching Agnès Varda’s Daguerréotypes, from 1976, in which she takes strolls in her neighborhood. She records ordinary interactions, at the local bakery, for example, as if they’re great dramas. “The stars are bread, milk, hardware, and white linen,” she says. “Also short hair, and always the accordion!” I also love Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares—that’s my guilty pleasure. Unlike in Hell’s Kitchen, which is a lot less fun, in Kitchen Nightmares Gordon Ramsay becomes a kind of folk hero because he’s honest with people. He goes around telling people the truth in a world where most of us would rather go bankrupt or face ruin than listen to criticism. He’s actually a good writer when he advocates for the simple, the honest, and the local. I think William S. Burroughs said you can’t fake good writing any more than you can fake a good meal. What have you been watching recently?

MM: Ingmar Bergman’s Fårodökument 1979. This is the sequel to Bergman’s first Fårodökument, from 1969, and it is, for my money, one of Bergman’s deepest and most humane films. I recently read Tove Jansson’s novel The Summer Book—it captures the same tone and complexity of Fårodökument 1979. I’m stunned by how complementary those two works are. Both use the vignette to navigate moments of quiet joy and muted sorrow. I find I’m drifting toward very quiet and acutely minimal things more and more.

JMT: But there’s something that fiction and poetry can do that film cannot, of course. I’m not sure I could describe it very well. Something about how words convey felt experience … how the entire imaginary world in fiction is conjured by words alone.

MM: Tarkovsky wrote that the image is an “entire world reflected as in a drop of water.” I love this definition of the image. It transcends genre. It even transcends medium. Images are our shared experiences. Sometimes I want that shared experience in a book, sometimes on a platter spinning vinyl, and sometimes in a movie. And speaking of shared experiences—I know you’re interested and invested in artistic collaboration. You coauthored a book on The Big Lebowski with Ben Walters. And your book on the documentary Salesman highlights the artistic collaboration between the Maysles brothers and their film editor, Charlotte Zwerin. And now you’ve coauthored a book of short stories with a poet. Does it surprise you that you’ve ended up collaborating on so many projects?

JMT: I’ll write it myself if I have to, but I prefer to collaborate. Collaboration is anathema to a lot of fiction writers, and I do realize that it’s a little bit risky to trust another person enough to follow through on a big project. I’ve had plenty of projects that didn’t pan out, but you have to keep trying. By sharing and giving away an element of control, I can do things I never would have thought of on my own. Collaboration comes much more naturally to musicians and filmmakers—and maybe to poets, too?

MM: Eavan Boland wrote somewhere that poets coauthor their work with the cultures they come from. As for literal collaboration, on the other hand, that’s a whole different story. Having seen Our Secret Life emerge from a concept into a book, I have a new admiration for literary collaboration. I suppose the risk—and the nightmare scenario—is that a collaborative project can turn into something written by committee, a homogeneous blob. But there’s something else that can happen, too. You have to drop your guard. You have to become open, flexible, willing to travel down whatever path opens before you. I think this leads to invention.

Michael McGriff is an author, translator, and editor. His most recent book, Home Burial, was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice selection.

J. M. Tyree was a Truman Capote–Wallace Stegner Fellow and Jones Lecturer in Fiction at Stanford University. He works as an associate editor of The New England Review.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers