The Paris Review's Blog, page 646

November 7, 2014

Orwell by Way of Langley, and Other News

A still from the British film adaptation of Animal Farm, 1954.

Fact: the New York Public Library has among its possessions a letter opener with a handle made from the paw of Charles Dickens’s dead cat. (“The story is that he had trained his cat to put out his night candle with his paw.”)

“Genre doesn’t have to be vexing. It can be illuminating. It can be useful for writers and readers to think in terms of groups and traditions. And a good genre system—a system that really fits reality—can help us see the traditions in which we’re already, unconsciously, immersed.”

Sixty years ago, the CIA helped to bankroll England’s first-ever animated film: an adaptation of Animal Farm. They thought it would make for great anti-Russian propaganda, especially if they changed the ending, and they knew it would be cheaper to make it in England. “The CIA agent who bought the film rights supposedly promised Mrs. Orwell that he would arrange for her to meet her favorite star, Clark Gable.” Did such a meeting ever occur? When will our government finally tell us the truth?

Oops: “Do you remember when the Authors Guild sued Google over Google Book Search, which is basically the right to make an index of stuff in books? They said to Google, ‘If you’re going to do this, you’re going to do it on our terms, and you’re going to have to give us a whole $70 million.’ … Google said, ‘$70 million? Let’s shake the sofa and find some change for you.’ Meanwhile, you are guaranteeing that nobody else in the future history of the world will be able to afford to index books, which is one of the ways people find and buy books. Now Google owns that forever, for a mere $70 million! Nice work, Authors Guild. You’ve just made us all sharecroppers in Google’s fields for the rest of eternity.”

The latest battle in the Usage Wars is really heating up: “If you say ‘It’s not you, it’s me,’ you are probably a native speaker of English or someone with a good command of how native speakers actually speak. If you say ‘It’s not you—it’s I,’ you will quickly achieve the goal of making the other person not want to spend any more time with you. Yet this bizarre formulation is just how Nathan Heller of The New Yorker would have you speak.”

November 6, 2014

Berlin’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams, Part 1

Life on the Karl-Marx-Allee, Block C South. Read Part 2 here.

[image error]

© WalcherBild Fridolin Walcher 2014

In the late eighties, the German Democratic Republic was bleeding people like money; the Iron Curtain was coming apart at the seams. November 9, 1989, would be the turning point, the evening on which the Socialist party allowed what had once been unimaginable.

In Block C South of the Karl-Marx-Allee, Otto Stark sat in the quiet of his apartment, tuning in to the historic national blunder that precipitated the fall of the Berlin Wall: one of the few international press conferences in East Germany’s history, with one very ill-prepared party spokesman, Günter Schabowski, at the microphone.

Schabowski: (reading from a memo) “Permanent departures can be made through all border crossing points of the GDR to the [West German] Federal Republic of Germany. This eliminates the temporarily allowed issuance of appropriate permits in foreign missions of the GDR or permanent exit with the identity card of the GDR via third countries.” […]

Reporter: When does this take effect?

Schabowski: (leafing through his papers) To my knowledge this takes effect immediately … without delay.

Further along the Karl-Marx-Allee, people were buzzing at the Kino International. They had come from the West to see the first—and what would be the only—gay film of the GDR. Later, these West German visitors would witness, by accident, the historic event, as thousands of East Berliners gathered at the border-control points and the confused guards finally relented. Thousands of East Berliners strolled through the gates of the Berlin Wall, their blue GDR passports waving in the air. Scaling the Wall, sitting on the Wall, ecstatic reunions between families after three decades apart.

But things were quiet in the Stark household on the Karl-Marx-Allee. Mr. Stark, the famous actor and later director of the Cabaret Distel, and his wife, the famous actress Ilse Maybrid, did not go out that evening: they would wait until the next day to see for themselves what was going on at the Wall. Otto had had a long day; it was nearing midnight when the gates opened, he was already in his late sixties, he’d just returned home from work. The Starks held a privileged position in the GDR. They were a prominent couple, they traveled to the West on professional engagements, and they lived in a penthouse on the showcase boulevard—something reserved for celebrities and the “best workers,” as Otto Stark, now ninety-two, tells me from his living room of fifty-four years. The same living room in which he and his wife first watched the collapse of the GDR on television, twenty-five years ago this Sunday.

Less than one month before, tanks had rolled down the Karl-Marx-Allee for the fortieth anniversary of the GDR. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had hugged General Secretary Erich Honecker, the two sides coming together after years of stubborn disagreement. “If we stay behind, life will punish us immediately,” Gorbachev told Honecker that day. The last Day of the Republic, the last military parade on the crumbling Karl-Marx-Allee.

* * *

Exiting the subway on Karl-Marx-Allee can be something of a disorienting experience, given the homogeneity of the buildings in every direction. The curve of the street reveals Strausberger Platz, which bends around a large centerpiece fountain with decorative metal panels like studs or brass knuckles, which give the fountain its title, “Floating Ring.” In the direction of the curve lies Alexanderplatz and the district Mitte, while the rest of the monumental boulevard, and Friedrichshain, unfolds along the straight traversal of the long, broad street.

The sidewalk is quiet early on a Wednesday, save a few mothers and their strollers. The haziness of the skyline is accented by the biscuit-colored monotony of the buildings that follow one after the next. The street is disarming for its consistency, but there are a few anomalies interspersed: the two modernist Laubenganghäuser nearing Frankfurter Tor, which were built in the Bauhaus tradition before the concept for the Stalinallee emerged; and the later Plattenbauten, or prefabricated buildings, nearing and past Strausberger Platz, which were built after a dwindling of resources and dwindling esteem for the neoclassicist style. There are glitzy modernist buildings here, too, like the Kino International, the Café Moscow, and the House of the Teacher, which became popular attractions after the regime backtracked on its disavowal of the supposedly bourgeois and formalistic International Style, but these are in the other direction, beyond Strausberger Platz and what most people think of when they think of Karl-Marx-Allee.

Ugly prefabricated buildings fill either side of the next block, offset from the sidewalk as if in deference or apology to the impressive compositions that silhouette them before and beyond. On that block, the monumental project of the Karl-Marx-Allee is confused, moderated; on the next, it’s resurrected in its all-encompassing might.

Stalinallee, November 1952.

The Karl-Marx-Allee came about in the early fifties, when East and West Berlin were just beginning to be carved out in the way we now remember them: the Allied zone had just become its own tentatively occupied West German state and the Soviet zone had shortly thereafter become its own East German state. On Stalin’s seventieth birthday, just seventy-five days after the founding of the German Democratic Republic in October 1949, East Berlin’s Grosse Frankfurter Strasse and the connecting Frankfurter Allee were symbolically renamed Stalinallee. The streets had been largely destroyed during the bombings of World War II. They offered up a sorry sight of half torn-down buildings and lots of rubble. An ideal boulevard had to be constructed anew, a boulevard to show the world just what Socialism could be.

Seventy percent of the bricks were resurrected from the ruins of Berlin. They were gathered in a voluntary effort: thirty-eight million bricks picked out of the debris during four million hours of voluntary work to construct this, the Socialist utopia of the new East German state.

Isa Henselmann, the daughter of the GDR’s most prominent architect, Hermann Henselmann, recalls her childhood breaking stones: Steine klopfen, a foreign notion to English ears, is as natural as woodcutting to any German. “We all broke stones back then, from our grandfathers to the children,” she said in an interview with Die Zeit last year. “We wanted to be the ‘Good Germany.’ We wanted to make a whole lot better. We still had so much guilt.”

When the houses were completed they were top of the line, with elevators, heat, running water, and an iconic architecture, well proportioned and well located on the most exemplary boulevard of the GDR. They were monumental, overpowering in their grandeur and consistency, with tile upon tile of ornamental, decadent might. Not decadent, really: the houses of the Stalinallee were “Worker’s Palaces,” available at an extremely fair rate, all in the name of equality. And at first, people say, they really were.

* * *

The worker’s uprising came on June 17, 1953. Isa Henselmann remembers this as the moment she first questioned the benevolence of her liberators. When she saw the street—her street, the Stalinallee—full of people, and after them the tanks, she thought it was a political celebration, so she put on her pioneer’s outfit with its characteristic red kerchief and she went outside. There, she saw the green tanks with red stars. “I had learned that these were our emancipators after the war; these are the good ones.”

When she waved to the tanks rolling by, she was greeted with knocks on the head and reprimands by her fellow compatriots. “They’re against us!” they told her.

The GDR bound itself to the mighty Soviet crutch through the interference of the Red Army on the day of the worker’s uprising, which certainly helped trample it underfoot. The uprising had been organized, among other reasons, in response to the increasingly untenable construction demands for the workers of the Stalinallee and it was quashed. Many historians mark this as the date from whence the young nation’s gloomy path was set, a day that precipitated the siphoning off of its population through the thousands who fled to the West, leading to the Berlin Wall as a countermeasure.

The uprising was celebrated in West Germany within the week through the christening of an iconic West German boulevard: the Street of the Seventeenth of June, which runs from Brandenburg Gate through the Victory Column, and begins right behind the wall that would later be erected.

* * *

Every year on the first of May and the seventh of October, tanks rolled down the great Stalinallee, celebrating first the workers and second the state of the GDR. The parades were televised across the country. In later years, the tanks were left out of the May Day celebrations, but the processions continued with politicians and celebrities alongside the common people, balloons, parade floats, members of the Free German Youth holding up massive pictures of the country’s leaders—a “demonstration” in the name of Socialism, peace, and worker freedom.

Stalinallee came twelve years before the Wall—shortly after the Wall went up, it became the Karl-Marx-Allee. In an effort to distance the regime from the despotic image that Stalinism had acquired in the decade since Stalin’s death, his statue was torn down and modern buildings were erected in the remaining one kilometer of the boulevard. The Soviet wedding cake–style (known alternately as Socialist Classicism or disparagingly in German as Zuckerbäckerstil) had proven itself far less popular than the modernism embraced by the West; the Stalinist neoclassicism was seen as outdated, perhaps too massive. And since it had been championed by the now-eschewed Stalin, a change of taste might not be so bad.

Karl-Marx-Buchhandlung, February 1954.

The curly orange sign outside the Café Sibylle brings something of this new aesthetic to the Stalin-era café, and just a short ways further, the unlit sans-serif of the KARL MARX BUCHHANDLUNG reveals a revamped identity if not in style, then certainly in name. From the Doric portico of Block C South, seven stories of Soviet wedding cake–style ornamental tiling shoot up. Twelve central reliefs portray the values of Socialist daily life: hard work, and labor, manual labor, quotidian labor, good cheer, conversation amongst laborers during a break from labor, good cheer, family.

In Five Germanys I Have Known, Fritz Stern, an American intellectual and German emigrant whose family fled during his childhood from the Nazi regime, recalls his first visits to the GDR and its iconic bookstore as a visiting academic at the Free University in West Berlin:

I also repeatedly visited the stately, spacious Karl Marx Buchhandlung on Stalinallee, where one could buy inexpensive editions of the great “classics of socialism” and translations of acceptable foreign works. The SED-controlled publishing enterprises produced a great flow of authorized books at low prices, hoping to leave no comrade behind. And in the secondhand section one could find “bourgeois” editions of old classics at bargain prices: I bought an old four-volume edition of Herder’s Werke with a modern stamp on the flyleaf: FROM THE GHETTO LIBRARY—no place specified. A grim irony: the works of an Enlightenment philosopher taken from the ghetto, perhaps the one place where he might have been read in the old spirit.

I also purchased a big volume entitled Deutschland, translated from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Its editors, Jürgen Kuczynski and Wolfgang Steinitz, noted that this “most comprehensive scientific work in the history of humanity” had been raised to a “still higher level” in its 1950 edition, as decided by the Soviet Union’s Council of Ministers. Of contemporary historical writing, it reported, “After the destruction of Hitler’s Germany by the Soviet Union, German historians have gained wider perspectives in free scientific research … However, reactionary ideas are once again prevalent in West German historiography, as Anglo-American imperialists conduct a policy of dividing Germany so as to allow the revival of fascism and militarism in West Germany.”

Still, West Germans and even the odd “Anglo-American imperialist” made the cumbersome journey over to the East, undergoing the stringent border control and mandatory currency swap after the construction of the Berlin Wall, to visit the spacious bookstore. It’s associated with names like Christa Wolf and Bertolt Brecht, who both numbered at times among the happier and the more miserable inhabitants of the GDR. Thomas Mann had shown himself open to East Germany, visiting both the Allied Frankfurt and the Soviet Weimar when he was honored with the Goethe Prize in 1949 and later exhorting his Frankfurt-based publisher to authorize the publication of his books in the East:

I know no zones. My visit counts to Germany itself, Germany as a whole, and not to any occupied territory … Who should ensure and represent the unity of Germany if not an independent writer, whose true home … is the free and unoccupied German language?

His death in 1955 prevented him from witnessing the development of the GDR and the heartache of the embodied Iron Curtain, but his early show of goodwill brought him enduring celebrity in the East; his face was put on a stamp and even a special 5-Ostmark coin at the centennial of his birth, and his works were always to be found at the Karl-Marx-Buchhandlung, one of those rare places where the two Germanys could truly mix.

The old bookstore now houses a film production company. Photo courtesy of the author

The Karl-Marx-Buchhandlung hasn’t been a bookstore since 2008—today it’s a film production company, Cobblestone, with its Berlin office run by Juri Wiesner. The 6500-square-foot space is kind of the ultimate worker’s paradise: a Ping-Pong table right in the middle of the foyer, a Foosball table overlooking an incredible boulevard view, and oddly pleasing curations distributed among its oak bookshelves—thirty-one brightly colored piggy banks filling one set of shelves, action figures in another, mounted butterflies, a model factory with tiny, electrically wired industrial sewing machines, and other odd tidbits lying somewhere between item and art.

When I stop by, Wiesner is already in the midst of a busy morning, his phone ringing again. I spend a long time examining a large painting of Yuri Gagarin, the Soviet cosmonaut who was the first human in space, portrayed here with young red kerchief–clad Soviet pioneers, an array of rockets, tanks and satellites at their feet. Wiesner explains the mixed heritage of the objects, East and West: the 1970s Gagarin painting purchased at auction, the Richard Neutra furniture and props—like the piggy banks—incorporated into the office space after commercial shoots, as well as things dug out from the bookstore’s original bookstore days.

“There are a few relics: the Manifest der kommunistischen Partei and a number of pictures of GDR authors taken at readings here. I found those in the basement and hung them up.”

Wiesner was born and raised in the GDR and recalls it as a somewhat odious state in which there was little freedom and little to do as a youth. “After the age of fifteen, sixteen, one rejected everything. One thought the East was dumb and wanted out,” he says, mildly. “One didn’t find the system so great.”

His choice, after a brief period following German reunification in which he completed his high-school diploma in the former West, to study here and to settle here does not represent a return to his childhood space, he says; it’s changed so much and, besides, Berlin was always different from the rest of the East.

“Berlin was always a showcase area. One could buy things in Berlin that weren’t available elsewhere,” he recalls. “Everything was bigger and more grand.”

It was also a place of less uniform thinking. “There were always people here who spoke out against the system, who were nonconformists,” he says, and, of course, it had its cultural offering, like the Karl-Marx-Buchhandlung or the operas and theaters. The Bookstore, the boulevard, and Berlin were three microcosms within microcosms that Wiesner associates with exception: “Not super East.”

In a sense, the space does recall Wiesner’s childhood, but not the one spent in a remote East German town. Wiesner, who’s half Russian, would visit his maternal relatives in St. Petersburg during the summer, memories of which are evoked by the bookstore and the Allee. His father was also an officer, and on occasion the family would visit GDR bases of the Soviet Army in Eberswalde and Bad Freienwalde. The forces, he says, were housed in buildings of this style. “Heavily paneled, hardwood—very similar.”

Café Sibylle. Photo: Cadaverexquisito, via Flickr

Today, plaques on the street point to similarities to Moscow’s Gorky Street, while literature points to architectural likenesses to Moscow’s Seven Sisters towers, commissioned by Stalin following World War II as the buildings that would define the capital’s skyline. These, along with the main building of the Moscow State University and the Palace of Culture and Sciences in Warsaw, were models for the GDR’s showcase boulevard.

It’s ironic but not all that surprising that an East German delegation was sent abroad to study the architecture and city planning of Stalingrad, Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev in order to come up with an architectural manifesto demanding fidelity to the local German building traditions. The “Sixteen Principles of City Building” state that the “city planning and architectural design of our cities must express the social order of the German Democratic Republic, the progressive traditions of our German people, and the goals set for the reconstruction of the whole of Germany.”

Of course, an understanding of those “progressive traditions” was subject to the whims of politics, and goals for reconstruction were set with a heavy hand. Before he designed the bookend neoclassicist buildings of the original Stalinallee, Hermann Henselmann was immersed in the modernist German tradition of the Bauhaus, serving as the director of the Weimar College of Architecture and Fine Arts (the original Bauhaus), where he’d called for a stronger return to the Bauhaus program initially set forth by Walter Gropius in 1919. But he had to rescind those modernist ideals to assume projects on the Stalinallee, later becoming chief architect of Socialist Berlin. The Soviet wedding-cake towers showed fidelity to the German tradition, but not to the Bauhaus; they paid homage to Friedrich Schinkel, a Prussian architect responsible for many other landmarks in Berlin, whose work predated modernism.

When modernism was restored to vogue in the Socialist party, Henselmann was restored to his modernist principles—he designed the Karl-Marx-Allee’s House of the Teacher and helped to design the iconic TV tower just beyond. What do these buildings say? Freedom from one totalitarian regime is just another, the next.

This is the first in a two-part series. Read Part 2 here.

Brenna Hughes Neghaiwi is a writer based in Berlin. Currently, she spends her time thinking and writing about the once divided capital and, separately, the merits of metaphysics. She’s written for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Berfrois, and others.

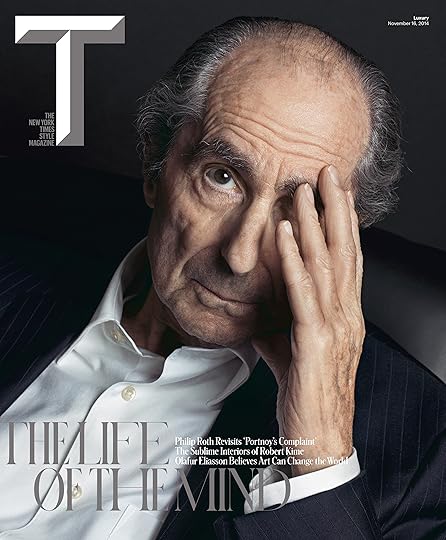

Cover Model

Photo: Inez and Vinoodh for T: The New York Times Style Magazine.

T: The New York Times Style Magazine just sent us a sneak preview of their newest cover model: Philip Roth. He’s in handsome company, perhaps dangerously so. The last guy on the cover was Channing Tatum.

But if Roth has that stressed, I-can’t-bear-to-look thing going on—anxiety chic—it’s not because he’s out of his depth in the modeling game. It’s because he’s been rereading his own work, always a dicey proposition. Specifically, he’s been rereading Portnoy’s Complaint, to which his reputation remains staked, many decades and nearly two dozen novels later. Roth doesn’t have a problem with that, but he does have a problem with those who have cast the book as gratuitous or indecorous:

I portrayed a man who is the repository of every unacceptable thought, a 33-year-old man possessed by dangerous sensations, nasty opinions, savage grievances, sinister feelings and, of course, one stalked by the implacable presence of lust. In short, I wrote about the quotient of the unsocialized that is rooted in almost everyone … One writes a repellent book (and Portnoy’s Complaint was taken by many to be solely that) not to be repellent but to represent the repellent, to air the repellent, to expose it, to reveal how it looks and what it is. Chekhov wisely advised that the writer’s task lies not in solving problems but in properly presenting the problem.

With his usual candor, Roth meditates on Alexander Portnoy’s standing today, in these “erotically unfettered” times. His essay is one in a series wherein authors reread their own work; there’s also Lydia Davis on Break It Down, Robert Caro on The Power Broker, George Saunders on CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, Marilynne Robinson on Housekeeping, Jennifer Egan on A Visit From the Goon Squad, and Junot Díaz on The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. You can read all of them here.

Next month, these writers and others are auctioning annotated first editions of their books to benefit PEN American Center. The auction, “First Editions, Second Thoughts,” takes place December 2 at Christie’s New York; previews begin November 17.

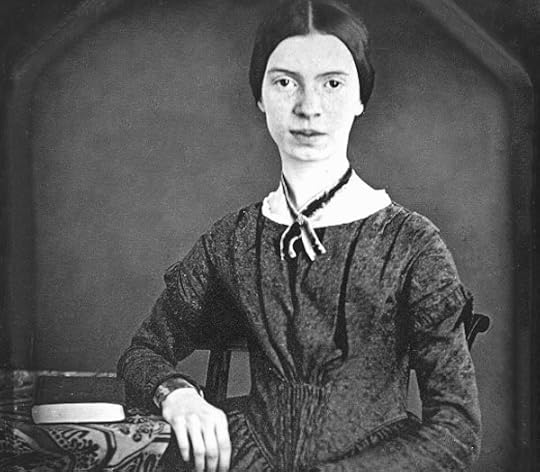

Context

A daguerreotype of Emily Dickinson from Mount Holyoke Seminary, ca. 1847.

I’ve always loved this line of Emily Dickinson’s: “November always seemed to me the Norway of the year.” Where did I first encounter it? Who knows—maybe a kid’s book of quotations or a calendar or something else. I know the context was cheerful rather than melancholy, although on a day like this one—gray, rainy, fall shading into winter—it felt apt, in its gnomic way.

What did Norway convey to Dickinson, who had never left New England? A bleaker, more romantic version of the same? A place of Norse legends and epics? Perhaps she’d met Scandinavian immigrants and this informed her remark. But however she intended it, it’s so evocative. It was not until very recently that I read the fuller context, from an 1864 letter to her frequent correspondent Elizabeth Holland:

It is also November. The noons are more laconic and the sunsets sterner, and Gibraltar lights make the village foreign. November always seemed to me the Norway of the year. ------ is still with the sister who put her child in an ice nest last Monday forenoon. The redoubtable God! I notice where Death has been introduced, he frequently calls, making it desirable to forestall his advances.

In the same letter, she mentions the recent death of the family’s maid, Margaret O’Brien—“I winced at her loss, because I was in the habit of her, and even a new rolling-pin has an embarrassing element, but to all except anguish, the mind soon adjusts.” Another friend is ill. And, of course, there would have been the background of the Civil War, felt even from within her home. The letter ends, “Sharper than dying is the death for the dying’s sake.”

The first English translation of Asbjørnsen and Moe’s landmark Popular Tales from the Norse appeared in 1859. It’s filled with trolls, enchanted animals, captive princesses held under spells. One of the best known is “East of the Sun, West of the Moon,” a Cupid-Psyche story in which a maiden is only allowed to interact with her husband by darkness. Others feature mountain people, envious of those who get to live by daylight. Did it make its way to Amherst? I have never read of it in Dickinson’s letters, but perhaps a scholar can tell me otherwise.

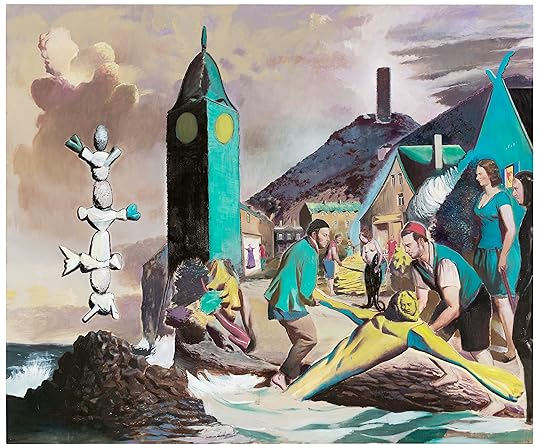

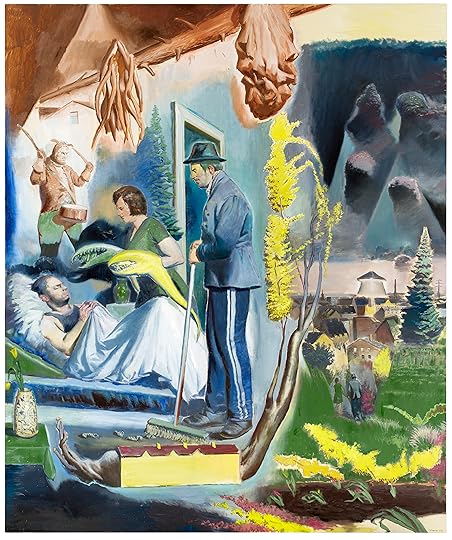

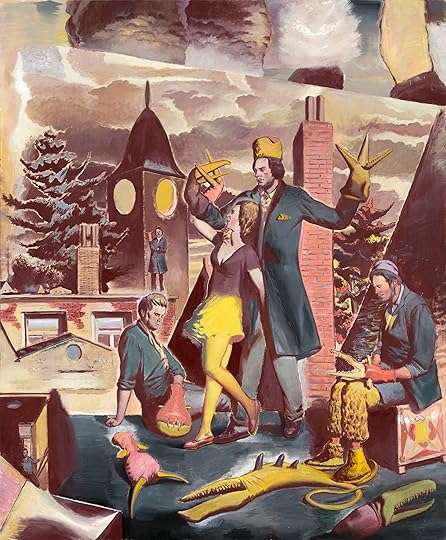

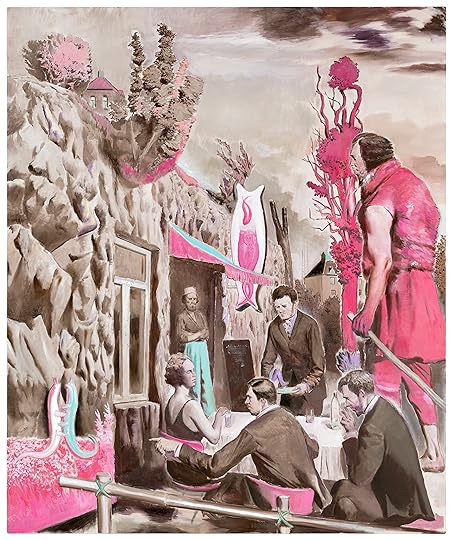

“At the Well”: Four Paintings by Neo Rauch

Neo Rauch, Marina, 2014, oil on canvas, 98 1/2” x 118 1/8”. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Neo Rauch’s “At the Well,” featuring new small- and large-format paintings, opens today at David Zwirner Gallery.

Rauch was born in Leipzig in 1960; his parents died in a train accident when he was four weeks old. Growing up in East Germany, he wasn’t exposed to much of the Western avant-garde, and though he’s denied that reunification influenced his development, I think it’s no coincidence that his show comes now, on the eve of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

His aesthetic couches the East with the West, and they make for strange bedfellows: the work is full of doom, but it’s never quite nefarious. If anything, a disquieting calm obtains. “My pictures supposedly have a vital quality, like an animal, a living thing,” Rauch told the Art Newspaper in 2011. “There is no need to understand, only to feel that this creature is, to the greatest possible degree, at peace with itself.”

Whether we’re at peace with it is another question. Looking at Rauch’s paintings, you feel as if you’ve gotten lost in the corridors of a vast, oppressive Soviet bloc building and opened the wrong door: you’ve stumbled upon the neon guts, the recondite boiler room, of social realism. Everyone is hard at work—but what are they working on? Again and again, his paintings find stone-faced men and women in dutiful pursuit of some arcane greater good. They plod through slanted, parti-colored worlds of clock towers and quaint rooftops, abrading the land without doing violence to it. This is labor as ritual, or ritual as labor. As a statement by the gallery says,

His paintings are characterized by a unique combination of realism and surrealist abstraction. In many of his compositions, human figures engaged in indeterminable tasks work against backdrops of mundane architecture, industrial settings, or bizarre and often barren landscapes.

Rauch said in a 2009 interview,

What finally condenses on the canvas is highly subtle and in need of protection. Sometimes I am surprised by the result of my art. There is a figure, which appears again and again: it might be a revenant or a reincarnation. He finds his way on to my canvas subconsciously. Only when I look at the finished work I realize: here he is again. It is true, his is the face of a decade and that decade is the fifties.

“At the Well” is up through December 20.

Neo Rauch, Hüter der Nacht, 2014, oil on canvas, 118 1/8" x 98 1/2". Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Neo Rauch, Über den Dächern, 2014, oil on canvas, 98 1/2" x 118 1/8". Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Neo Rauch, Der Felsenwirt, 2014, oil on canvas, 118 1/8" x 98 1/2". Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

All images © Neo Rauch

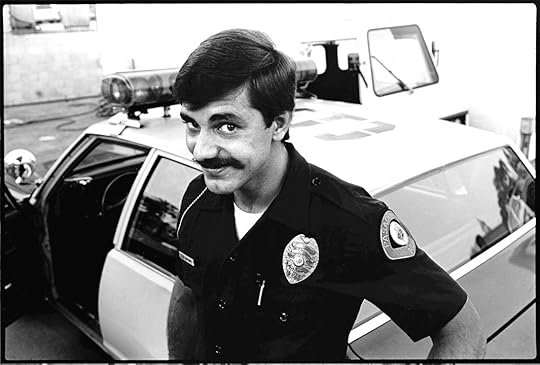

The Fuzz that Was, and Other News

January 17, 1986: Officer Gary Capuano. Photo: William Karl Valentine, via Slate

A certain Gen-X urtext is now twenty years old and all the more interesting for it: “I discovered that Reality Bites, weirdly, provides interesting commentary about the economy. In fact, it’s a film about money. To be a little more specific, the movie explores a deep, complicated ambivalence about work, freedom, capitalist impulses, and authenticity … Their story looks a lot less romantic from the vantage point of middle age. Generation X has turned out to be not so much indifferent to money as screwed by it.”

In praise of finishing every book you start: “The most common defense of book-dropping I hear is that because there are more good books than any one person could possibly read, it’s stupid to waste time on a dull or otherwise unsatisfactory novel. That argument makes sense if the novel is utter trash—if it’s so bad that the reader needn’t respect the author and would possibly get dumber by going forward. But if a novel starts well and descends into trash, then it seems to me that it’s worth continuing to see if it gets better, or to see where the writer went wrong.”

Your bladder is more than just an organ. It affects your stance on one of the most knotted, hotly debated questions in philosophical history. “Even healthy subjects have less belief in free will when they’re subtly reminded of their own physical limitations. [Two scientists] had people respond to a battery of questions not just about free will, but also about their current corporal desires. The desires that negatively correlated most strongly to belief in freedom were: a) the desire to urinate, b) the desire to sleep, and c) the desire to have sex.”

In 1985—years before Cops had proven that America loves to watch its enforcers in action—a photography major at Arizona State went on spring break and began to photograph the Pasadena Police Department. Now he’s published the photos: “Welcome to hell.”

Total number of kisses in Jane Austen novels: fourteen. Total number of speeches in Shakespeare: 34,895. And other statistics that won’t do much to improve your enjoyment of literature.

November 5, 2014

Nonfiction

An anonymous nineteenth-century painting.

The hard truth is that not everyone has a novel in them. “I have no gift for invention,” I say to anyone who ever asks after my own ambitions—and why do people ask? For that matter, is my response even appropriate? I’m not sure what that means, “a gift for invention”: certainly I’ve never visited the Genius Bar without concocting some elaborate and gratuitous lie to explain the condition of my computer.

Which is not to say I’ve never written any fiction. I have, under duress. It was a requirement for my degree. The instructor was an older lady in caftans and arty jewelry with pumpkin-colored hair who had at one point written an epic women’s best seller with a lurid, seventies-style jacket. She’d also written a book of cat poetry. I didn’t mind any of that; the problem was that every detail of the class was as lazy and clichéd as that constellation of characteristics.

A few people in the class were predictably pretentious. They turned out derivative takes on macho writers and they were unnecessarily confrontational when discussing others’ submissions. One guy’s work was disturbing, but tritely disturbing. A few in the class spoke and wrote poor English. One girl was writing a fantasy novel; she was my favorite.

We were required to write a story every week. As much as I hated other people’s work, I hated my own more. I resented being forced to show writing I knew to be bad, and I went to ever-greater lengths to avoid committing myself to anything resembling earnestness or feeling. There were multipage descriptions of meals. There was this weird period piece “written in the style of 1850s potboilers,” whatever that meant; I hadn’t actually read any in preparation. There was a series about a dollhouse decorated for different obscure liturgical holidays; one of the dolls abruptly committed suicide at the end, just to shake things up. The teacher and the fellow students seemed oblivious to my hostility—I admit, it was something of a deep game—but they frequently urged me to express more emotion in my work.

Our final project was a longer piece. Mine was—well, I guess you’d call it slash fiction, though it defied easy characterization. First I’d attempted a novella about Kay Thompson, the author of Eloise, going crazy and drinking a Negroni in Florence with a concerned gay man. That didn’t really come together, so I switched my energies to a fictionalized account of Joyce Carol Oates’s first year as a graduate student. In this piece, “In Which a Fictionalized Joyce Carol Oates TAs Her First Class,” Joyce Carol Oates really hates everyone in her writing seminar and develops an obsessive crush on a mature student, despite her scorn for his terrible writing. She contemplates murder. She is an excellent dancer. At the end she walks across the campus resolutely. I worried it read as too conventional so I threw in a dollhouse and set the whole thing on Shrove Tuesday. “Of course gritty reality always wins,” says Oates in the story’s final lines. “But I don’t understand why everyone assumes the smart people get to plot life … romances and fantasy novels are best sellers. Why don’t those women get to write the plot sometimes? Escapism is a reality too.”

Deconstructing Édouard Levé

From the cover of the English-language edition of Autoportrait.

I find myself ugly more often than handsome. I like my voice after a night out or when I have a cold. I am unacquainted with hunger. I was never in the army. I have never pulled a knife on anyone. I have never used a machine gun. I have fired a revolver. I have fired a rifle. I have shot an arrow. I have netted butterflies. I have observed rabbits. I have eaten pheasants. I recognize the scent of a tiger. I have touched the dry head of a tortoise and an elephant’s hard skin. I have caught sight of a herd of wild boar in a forest in Normandy. I ride. I do not explain. I do not excuse. I do not classify. I go fast.

Édouard Levé’s “When I Look at a Strawberry, I Think of a Tongue” appeared in our Spring 2011 issue, and it’s been a staff favorite ever since—a beguiling and sui generis self-portrait. It’s taken from the pages of Autoportrait, which Levé wrote in 2002 while he was traveling across America, taking the photographs that became “Série Amérique.” He’s still best known as a photographer, but his four works of prose—Oeuvres, Journal, Autoportrait, and Suicide—have begun to find the wider readership they deserve. Levé delivered Suicide to his publisher eight days before he took his own life, in 2007, at the age of forty-two.

If you’re in San Francisco, join our editor, Lorin Stein, in conversation with Jan Steyn for “Deconstructing Édouard Levé,” tonight at The Lab. (Lorin and Jan have both translated Levé.) Two Lines Press’s Scott Esposito, a certified Levé-ian and the coauthor of The End of Oulipo?, will moderate the discussion:

“We will immerse ourselves in the artistry and ideas behind his books—and we will also invite the audience to participate in creating some Levé-ian artworks and texts of our own. No prior knowledge of Levé or experimental prose necessary!”

Entry is free, and the event begins at seven this evening.

Writing a Life

On reimagining what a biography can look like.

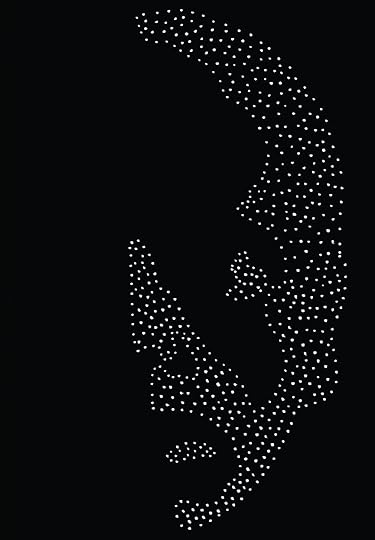

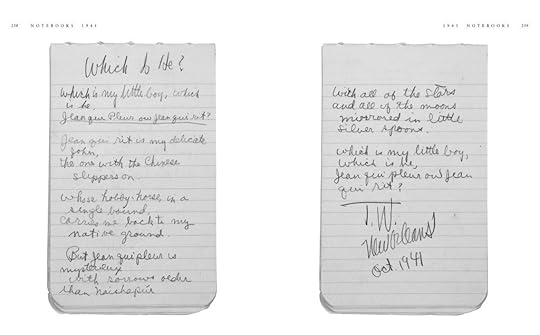

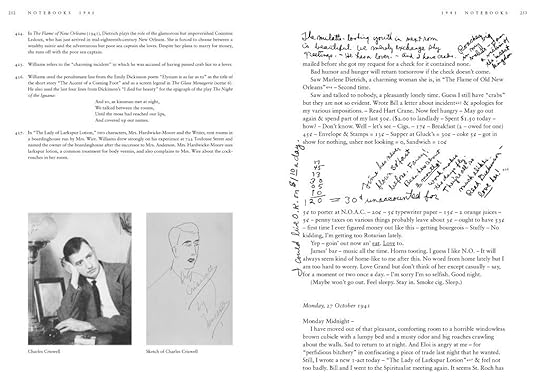

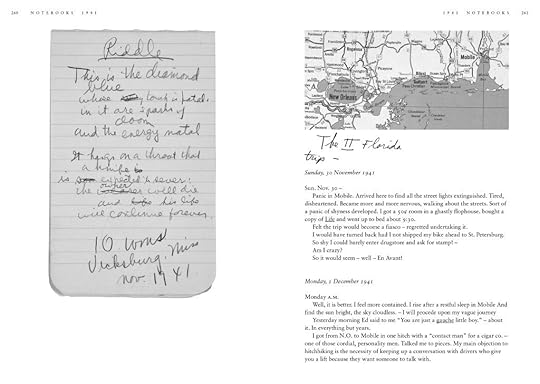

From Tennessee Williams: Notebooks. Copyright the University of the South; Courtesy Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library

In December 2012, I spent several days in Laurel, Mississippi, with my wife, researching her grandmother’s family history and childhood. I also did a lot of thinking about Stella and Blanche DuBois, the sisters who, as imagined by Tennessee Williams in A Streetcar Named Desire, also hailed from Laurel. They would have been roughly the same age as my wife’s grandmother. When we left Laurel, we followed Stella and Blanche’s path down to New Orleans. While in the city, we made several visits to Faulkner House Books in the French Quarter; I’d seen a brick of a book there called Tennessee Williams: Notebooks, edited by Margaret Bradham Thornton, and couldn’t stop thinking about it.

Williams has been on my mind for the nearly two decades I’ve been researching W. Eugene Smith, who declared that the plays of Williams were a major influence on his photojournalism. I thought I knew the names of all the prominent Williams scholars, and I’d heard in 2011 that John Lahr was working on a major biography for Norton. So this huge volume of Williams’s notebooks (it weighs close to four pounds; Lahr’s recently published Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh weighs just over two, by comparison) and its editor were a bit of a mystery. A one-line bio on the jacket flap simply describes Thornton as “a writer and independent scholar,” with no other credentials and no photograph.

The book was puzzling in structure and detail, too. Williams’s handwritten diary entries are transcribed in chronological order on the right side of each spread—on the odd-numbered pages—in a font that couldn’t be larger than eight or nine points. On the left side of each spread are meticulous annotations by Thornton in an even smaller font, maybe six points, that correspond to numbers on the opposite page. The results are parallel tracks of text: one, a series of odd, cryptic personal notes jotted by Williams over the course of his life; the other, 1,090 annotations, occupying equal space, that contextualize Williams’s arcane references many decades later. All told, I later learned, the book contains 265,000 words.

From Tennessee Williams: Notebooks. Copyright The University of the South. Left page: Photo by Bill Wood (left); courtesy Harry Ransom Research Center, University of Texas Austin (right). Right page: courtesy Harry Ransom Research Center, University of Texas Austin.

Notebooks also includes facsimiles of Williams’s scribbled notes as well as reproductions of postcards he’d sent to friends and many archival photographs of the playwright and of pertinent sites such as his New Orleans drinking holes, the Rendezvous and Dixie’s Bar. There are 580 credited images in total (Lahr’s biography has ninety-seven). On the dust jacket is an unusually strong blurb from Walter Isaacson. Thornton, he avers, has created “almost a new literary genre: a mix of diary, biography, autobiography, scrapbooks, and documentary history. It is addictive and it bares Williams’s soul.”

I bought the book before leaving New Orleans, and I carried it in my bag for nearly a year. Isaacson was right; I couldn’t put it down.

* * *

I’ve worked with the Eugene Smith archives for the majority of my adult life (a blue note for me at times), and that background helps me appreciate the difficulty and significance of Thornton’s achievement. I’m drawn to books that deal in fragments and digressions, authors that patch together something larger from these pieces while also letting them stand on their own. This is what Thornton has done.

On page 549 of Notebooks there are entries by Williams from March and April of 1952, when he was working on his intended experimental opus, Camino Real:

Sat. March 8. 4am.

Shit!

drunk—sleepy

a moderately pleasant encounter with a ¾ German

Piddling work on a poem this A.M.

dull, rainy P.M.

movie–

Now Casanova’s memoirs

On the facing page is Thornton’s annotation, entry 803:

Williams had written to Cheryl Crawford on 10 February 1952 (NYPL) about being encouraged that she was interested in Camino Real. He added:

I have gotten hold of the unabridged (12 volumes) Memoirs of Casanova and Dumas novel ‘Camille’ and the material in the play is now based on the real histories of those characters. I think the play is essentially a plastic poem on the romantic attitude toward life.

Then, Thornton adds,

Jacques Casanova de Seingalt (1725–98) was an Italian adventurer who, after being expelled from a Venetian seminary for misconduct, led a life as a charlatan, gambler, and lover who traveled around Europe. His fortunes vacillated, and he ended his career as a librarian at Count Waldstein’s castle in Bohemia. His Memoires (1826–37) are considered unreliable but of great historical interest.

Back over on the right side of the spread, there is Williams’s next entry:

April 16 or 17

… I’ve been working on “3 Players of a Summer Game”—The Writing is stiff. But Camino seems to be getting under control and if I have some good days in New Orleans or Columbus, it will be out of the woods when I arrive in New York, though I wonder if any producer could raise enough money for it …

Later—

… a series of queer feelings as if close to extinction—brea air hunger?—just as I am about to fall asleep, the last one with a twinge of pain in the chest—alarm me so much that I get up and go downstairs for a drink and take a seconal tablet.

This occurred after fucking.

Now I feel fairly calm but don’t want to sleep for a while if I can help it.

On the left side of the spread, Thornton’s note 804:

A few days earlier (14 April 1952), Williams had written Audrey Wood about the story which he started the previous summer in Venice:

I think it has the situation and characters for a play or a film, eventually. I spoke of it to Jay while he was here and he thought it would make a good title story for a collection of stories that he wants to bring out along with the selected poems.

These pages also bear two photographs of Williams, circa 1950: one of him and the mysterious Paul Bigelow in amorous party poses with sailors, and another of Williams at a black-tie dinner onboard the S.S. Liberte. The spread evokes sex, erudition, and travel, of both the geographic and literary kinds (Casanova worked in a library?), as well as Williams’s comfort with high and low life: sailors in bars and black-tie dinners—it was all the same to him.

Thornton presents nearly four hundred spreads like this in Notebooks. They function like Cornell boxes, made from scraps of a life, pieced together, curated, and offering multiple connections—back and forth and up and down. Thornton and Williams are in a dialogue made more subtle and dynamic in this format, and perhaps more informative, than in traditional biography.

From Tennessee Williams: Notebooks. Copyright The University of the South; Courtesy Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library

* * *

In October I made the five-hour drive from my home in Durham, North Carolina, to Charleston, South Carolina, to visit Margaret Thornton. Her first novel, Charleston, was published earlier this year. Thornton grew up in Charleston and was state tennis champion before leaving for Princeton. She worked at Goldman Sachs in New York and London, where she was one of only two female vice presidents, and graduated from Harvard Business School along the way. She met her husband in New York and they have raised four kids.

Thornton’s professional résumé makes her an unlikely candidate for a decade-long literary exploration, so I was curious to find out more about her. Before I left to meet her in Charleston, I called a couple of the principal figures who had facilitated Notebooks to see what I could learn. John Eastman, a New York entertainment lawyer who is the former executor of the Tennessee Williams estate, originally put the notebooks in Thornton’s lap. I asked Eastman, brother of the late Linda McCartney, why he thought Thornton was right for the project on Williams’s notebooks. “I’ve known Margaret for more than thirty years,” he explained. “The first serious conversation I had with her—I guess she was in her twenties and working for Goldman—was about Henry James and The Portrait of a Lady. I wouldn’t call the conversation an argument, but it was lively. She has an unusual mix of intellectual discipline and flights of fancy. Lots of people have one of those traits but rarely both. I knew she was perfect for the project.”

I also called Jonathan Brent, Thornton’s editor on Notebooks and the former editorial director of Yale University Press. He told me, “I was moved by her intensity. She was fixated on doing everything right, with care and love. There were so many obstacles to publishing the book the way she wanted it done. I could give you a list—everything was outside the mold. It was hard for some of my colleagues at Yale to see how the book would hang together. There’s a messiness to it, a variousness, that is difficult, but there’s a poetry to it, too, and that’s who Tennessee Williams was. I strongly believe you cannot tell the story of anyone’s life in a linear way, certainly not Williams’s. Margaret felt a debt of honor to him, and she created a love letter that you can read backward and forward. The result is something like a diary-novel, perhaps like those loose, baggy monsters of Eastern European and Russian literature.”

* * *

The main characters in Thornton’s novel, Charleston, are named Eliza and Henry, possibly taken—consciously or unconsciously, she’s not sure now—from George Bernard Shaw’s 1912 play, Pygmalion. But in Thornton’s story, which is set in 1990, there is a twist and a reversal: rather than being molded by Henry’s tutelage, Eliza grew up in Charleston’s high culture, attended Princeton, and then moved to New York and London. The novel is a meditation on the question of whether her first love, Henry, who never left Charleston, can recast a spell on her ten years later, after they cross paths at a wedding in the English countryside.

By page ten, Eliza is on a flight back to Charleston for her stepsister’s debutante party, having left behind her steady boyfriend, Jamie, an Etonian and world-traveling documentary filmmaker. All the pieces are in place for a story befitting the book’s cover: a Southern romance novel, a book-club pick, a beach read. What Thornton delivers, instead, has more in common with her Williams book—an obsessive and poetic scaffolding of details. Eliza is sitting at the window of the airplane as it approaches Charleston:

Thousands of feet below, roads that curved and faded without apparent reason snaked through large green untouched forest. Unlike the ordered rectangles and quadrilaterals and polygons of the English countryside that fit together like irregular pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, everything here was sinuous, unordered, untamed. The only straight line she could see was the Southern Seaboard Railroad and the power lines that cut sharp tracks through large expanses of timber. Toward the coast, the solid forests gave way to winding rivers and irregular patches of marsh. Eliza guessed that the dark river that curled in lazy loops was the Ashley River—it reminded her of the white sugar icing her grandmother used to let her serpentine across the top of her lemon cakes. Eliza watched the plane’s shadow flee in front of them across land that disappeared into marshes. She enjoyed the weightless feeling of the shadow’s swift escape precisely because running away from something or someone had never felt so easy.

The following eighty pages cover a mere twenty-four hours as the uncertain rendezvous of Eliza and Henry begins, along with a strong undertow of Eliza returning to her hometown. The Charleston-based poet, Nick Bozanic, has noted that “what reads at first like a field guide to the Low Country becomes a mesmerizing spell and explores stylistically and thematically the various ways in which we are beguiled, seduced, charmed into a relinquishing of the will, a yielding of one’s own purposes to those of the place and its allurements.” The novelist Bret Lott said the book reminds him of Roxana Robinson’s work in its anthropological study of upper-class culture. The Charleston visual artist Jonathan Green called the book “a beautifully written cross-cultural symphonic love song of a painted journey back home.” A few reviewers have complained that there is no plot, but Thornton makes no apology about focusing on character and having form serve, and not dominate, the story.

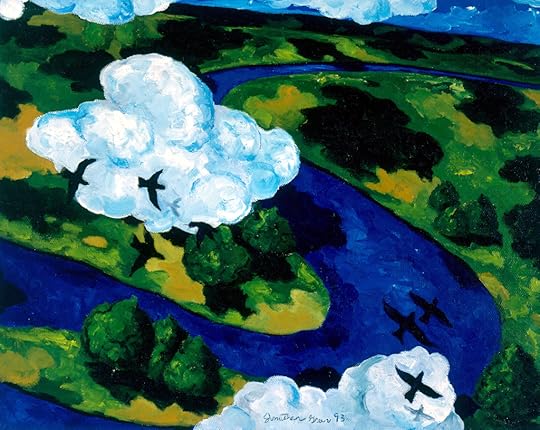

Jonathan Green, Snake River, 1993, acrylic on canvas. © Jonathan Green

At Princeton, Thornton majored in English and trained in drawing with artists Jerry Buchanan and Sean Scully, who liked her work enough to recommend she move to the Art Students League after college. She took a job with Goldman Sachs instead. “Wall Street was much more interesting in the 1980s than it is today,” Thornton said. “Back then Goldman—at least the investment side —wouldn’t hire you if you were an economics or business major. They wanted people with broader perspectives, with more creativity. I don’t have many regrets in life but one of them might be that I didn’t take the advice of my teachers and attend art school. Coming from such a conservative and formal place as Charleston, I found the art world intimidating, and I didn’t have enough confidence or courage to overcome that persuasion at the time.”

Visual art and the act of seeing are central, if subliminal, themes of Charleston. Eliza has a fellowship at the Courtauld, in London; Henry is an amateur photographer; local art, nineteenth-century slave pottery, and artists such as Bonnard are woven throughout the story. “Old World” Charleston has praised Thornton for her accurate rendering of the Holy City and the surrounding Low Country—from the South of Broad dinner parties to the swamps of the ACE Basin. With Charleston she seems again to have dealt in fragments and digressions, stitching them together into something larger while leaving the pieces to speak for themselves. Thornton includes a quote from artist Jasper Johns in the book and also uses it in conversation: “What interests me is the thing that cannot be located.”

“It's a mysterious sentence,” Thornton tells me, “so declarative, and it seems to me an apt metaphor for someone as rigorous and honest as Eliza. As she looks down from the airplane, I imagine that she is wondering about what, if anything, is left of her relationship with Henry. What is the thing? Can it not be located because it cannot be found, because it cannot be seen? Or because it doesn’t exist? Johns’s statement can also apply to the mysterious pull that Charleston has for Eliza, for the feeling—the fear—that home will never let her go.”

Sam Stephenson is a writer and partner in Rock Fish Stew Institute of Literature and Materials, a Durham, North Carolina–based documentary company. His is currently at work on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Ways of Witnessing

Geoff Dyer and John Berger, 1984.

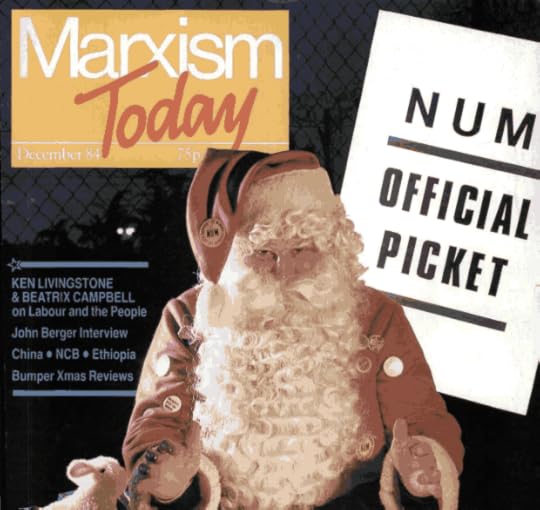

Marxism Today, December 1984.

I read Berger’s Ways of Seeing and then started to read more and more of him, and I found it all very stimulating and exciting. He was doing something that I hadn’t come across before in English writing—bridging the gap between criticism and fiction and so on. All with that level of political engagement that was absolutely de rigueur back in the early eighties. He was my favorite writer, and I interviewed him for Marxism Today. —Geoff Dyer, the Art of Nonfiction No. 6, 2013

John Berger is eighty-eight today—I’d been curious for a while about his interview with Geoff Dyer, so I finally did the obvious thing and Googled it. Lo and behold: the December 1984 issue of Marxism Today has been digitally archived by unz.org, with the Dyer-Berger exchange complete and unabridged. The interview, “Ways of Witnessing,” sits among such fare as “Hopes, Dreams & Dirty Nappies” (“What can utopias do for mothers and mothers do for utopias?”) and a column called “Video Viewpoint” (“Perhaps 1984 will be remembered in some small footnote as the year in which video tapes started to live up to the claims several people, mostly video producers to be sure, had been making… ”). The cover story: “Santa’s Dramatic Intervention.”

At the time, Berger was soon to release And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, but he doesn’t discuss the new book much. Instead—as you might anticipate given the venue—he and Dyer talk a lot of leftist shop: “My reading tended to be more anarchist than Marxist-Kropotkin and all the anarchist classics,” Berger says. And on why he never became a card-carrying Communist: “I had reservations about the party line in relation to the arts.”

Dyer would’ve been twenty-six when this interview came out; there’s not a lot of his voice here, and certainly none of his humor comes through. But you can sense, maybe only because of his later comments, his eagerness to please Berger, or at least to convey the scope of his intellect. Toward its midpoint, the conversation turns to romanticism, and here it’s somewhat less arid:

Marxism sees history as an arena of struggle but to what extent do you see romanticism or love as a refuge from history and “the laws of change which spare nothing”?

… During the Soviet revolution and the civil war people didn’t stop falling in love. Think of Mayakovsky who wrote extraordinary love poems at the same time that he was writing political poems. The problem is that in an individual life they often do not confirm one another. If one denies too much those subjective intuitions which romanticism is about and which are frequently expressed in love then something withers. The consistent, logical political line cannot bring them back. When that withering takes place there is political danger.

But Dyer’s boldest and best question is his last:

Finally I would like to take a line from the play you have written with Nella Bielski, A Question of Geography: “Each of us comes into the world with her or his unique possibility—which is like an aim, or, if you wish, almost like a law. The job of our lives is to become—day by day, year by year, more conscious of that aim so that it can at last be realized.” What do you see as the job of your life?

I don’t think I can answer that … Perhaps I am like all people who tell stories—and I often think now that even when I was writing on art, it was really a way of storytelling—storytellers lose their identity and are open to the lives of other people. Maybe when you look at their entire output you can see something that really belongs to that one person. But at any one moment it is difficult to see what the job your life is because you are so aware of what you lending yourself to. This is perhaps why I use the term “being a witness.” One is witness of others but not of oneself.

Read the whole interview here. “Berger is not an academic, but he’s deeply learned and passionate,” Dyer said almost thirty years later. “What you get in his books is a total engagement with whatever he happens to be writing about.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers