The Paris Review's Blog, page 642

November 20, 2014

Remembering Mike Nichols, and Other News

A publicity shot of a young Mike Nichols, ca. 1970.

Last night there was a modest ceremony for a little-known prize called the National Book Award. Congratulations to its winners this year: Evan Osnos in nonfiction, for The Age of Ambition; Phil Klay in fiction, for his collection Redeployment; Louise Glück in poetry, for Faithful and Virtuous Night; and Jacqueline Woodson in young people’s literature, for Brown Girl Dreaming. The Daily interviewed Klay earlier this year, and The Paris Review published five of Glück’s poems in our Winter 2007 issue—read one here.

While we’re at it, why won’t the National Book Foundation bring back its award for translation, which was eliminated in the eighties? “The prize was a model of award-as-activism … Its administrators leveraged the National Book Awards’s clout in service of a category of literature that desperately needed popular attention and validation.”

Mike Nichols has died at eighty-three. (Not to diminish his incredible accomplishments as a director, but NB: his “Mother and Son” skit with Elaine May is still funny more than half a century later.)

A new game, Ether One, brings us closer to the experience of dementia: “Your job is to dive into the mind of Jean Thompson, a sixty-nine-year-old woman diagnosed with dementia, and retrieve a series of lost memories … The collection gradually overwhelms the player’s ability to remember just where all of these things came from and why they seemed important enough to retrieve. Why did I bring this plate all the way back here? Whose hat is this supposed to be again? It’s a tidy simulation of the cognitive degradation of dementia.”

“How does one write a mouse-washing scene? There aren’t a lot of examples in literature, and in any event I didn’t want my mouse-washing scene to be contaminated by the work of other fiction writers.”

November 19, 2014

Talking Tate: A Fake Oral History

Photo: Library of Congress

There’s no Writers at Work interview with Allen Tate—who was born today in 1899—but his name seems to pop up in nearly everyone else’s. By my count, he has cameos in nineteen of our interviews; he shuffles onstage to offer an apercu or to help someone or to drink or to be carried down a flight of stairs. And then he leaves.

Tate ran in many circles, in part because his teaching allowed him to move around so much. At one point or another he crossed paths with an astonishing number of his fellow writers: Robert Penn Warren and Robert Lowell, most prominently, but also Randall Jarrell, John Gould Fletcher, John Crowe Ransom, John Berryman, and Andrew Lytle. His walk-ons in The Paris Review interviews testify to his influence not just as a poet but as a friend. If you read these mentions of him in succession, as a kind of patchwork oral history, you get a strangely gratifying secondhand sense of the man, as if someone had painted his portrait based only on a description. Let’s give it a try—

Robert Giroux (The Art of Publishing No. 3, 2000):

There’s a memorable phrase of Marianne Moore’s about Allen Tate. T. S. Eliot or somebody asked her, What do you think of Allen Tate? And she said, That man is freckled with impropriety like a trout. Allen Tate was a Southern gentleman with impeccable manners. Who knows what she meant? She was a colorful talker, an original.

Robert Lowell (The Art of Poetry No. 3, 1961):

I met Ford at a cocktail party in Boston and went to dinner with him at the Athens Olympia. He was going to visit the Tates, and said, “Come and see me down there, we’re all going to Tennessee.” So I drove down. He hadn’t arrived, so I got to know the Tates quite well before his appearance … Mrs. Tate was doing all the housekeeping. She had three guests and her own family, and was doing the cooking and writing a novel. And this young man arrived, quite ardent and eccentric. I think I suggested that maybe I’d stay with them. And they said, “We really haven’t any room, you’d have to pitch a tent on the lawn.” So I went to Sears, Roebuck and got a tent and rigged it on their lawn. The Tates were too polite to tell me that what they’d said had been just a figure of speech. I stayed two months in my tent and ate with the Tates.

[…] It was a very interesting year I spent with Tate and his wife. He’s a poet who writes in spurts, and he had about a third of a book. I was going to do a biography of Jonathan Edwards and he was going to write a novel, and our wives were going to write novels. Well, the wives just went humming away. “I’ve just finished three pages,” they’d say at the end of the day; and their books mounted up. But ours never did, though one morning Allen wrote four pages to his novel, very brilliant. We were in a little study together separated by a screen. I was heaping up books on Jonathan Edwards and taking notes, and getting more and more numb on the subject, looking at old leather-bound volumes on freedom of the will and so on, and feeling less and less a calling. And there we stuck. And then we decided to make an anthology together. We both liked rather formal, difficult poems, and we were reading particularly the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the evening we’d read aloud, and we started a card catalog of what we’d make for the anthology. And then we started writing. It seems to me we took old models like Drayton’s Ode—Tate wrote a poem called “The Young Proconsuls of the Air” in that stanza. I think there’s a trick to formal poetry. Most poetry is very formal, but when a modern poet is formal he gets more attention for it than old poets did. Somehow we’ve tried to make it look difficult … I think both Tate and I felt that we wanted our formal patterns to seem a hardship and something that we couldn’t rattle off easily.

Peter Taylor (The Art of Fiction No. 99, 1987):

[…] Allen Tate had called me from Chicago, and said, “Cal [Robert Lowell] is not himself at all,” and that he and Caroline Gordon had just put him on a train! Well, of course I was furious—Allen had no business putting him on a train. But I also knew that Allen had a great dramatic sense and I thought he must be exaggerating. I didn’t think it was true when he said that Cal was beside himself. He’d behaved strangely, frightened a child at the station, and he had picked up Allen and carried him down the platform. Allen was very small. Anyhow, Allen said I was to meet him with the police at the railroad station! Well that was something! Because some time before that, when the Tates were in Maine visiting the Lowells, Caroline had thrown a peanut-butter jar at Jean Stafford Lowell and Jean ran and called the sheriff, saying, “I fear for my life.” Allen was outraged. He said, “You don’t call the police on your friends.”

Robert Bly (The Art of Poetry No. 79, 2000):

I was buying toothpaste one morning, and the drugstore radio said that the police had picked up John [Berryman] trying to break into his own apartment the night before. This was a wholesome state university. I said, There goes John. He remarked that there was only one man in the country who would understand what had happened without asking a single question; he called Allen Tate in Minneapolis. Allen said, Come to Minneapolis, John. So John taught for years in the humanities department at the University of Minnesota and was marvelous.

Anthony Hecht (The Art of Poetry No. 40, 1988):

I have not felt the need to resort to cunning devices and secret caches of booze. I have never joined AA, or felt I needed to. But still, I had after a while acquired a reputation for drinking. I was amused by a letter from Allen Tate, in which he congratulated me on winning the Rome Prize (he had been my chief advocate on the committee that made the choice) and warned me not to drink too much at the Academy in Rome, lest I disgrace the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (which awarded the grant) and so offend the Academy in Rome as to persuade them never to admit another writer. You see, this was the first writing fellowship ever conferred. What amused me was that, as I saw it, Tate drank much more than I did in those days.

Richard Wilbur (The Art of Poetry No. 22, 1977):

Now as for our conflict, Edgar [Allan Poe]’s and mine, I object to him simply because he is far too much a fantasist. Or, as Allen Tate put it, the trouble with him is that his imagination does not proceed upward through the order of nature, moving toward the invisible through the visible. Instead, he tries to destroy the visible world on the assumption that if you do that, then the invisible world will rush in to take its place. Well, I question that formula, but I think it is an exciting mistake and resulted in a number of remarkable works.

Robert Bly:

[…] Bill Duffy and I started a magazine called The Fifties. On the inside front cover, we announced that “most of the poetry published in America today is too old-fashioned.” We developed various ways to infuriate people who had submitted old-fashioned poems. One was a card that read: “This entitles you to buy the new book of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, / as soon as it is published.” … One man wrote me, saying, You know who you are? You’re nothing but a Captain Bly pissing up a drainpipe! That was a strange metaphor. Allen Tate said something like: So people can write poems that are not in iambic? A cat can walk on its front legs too. So what? That was another strange metaphor.

Robert Lowell:

I could see how Tate was done, though Tate has a rhythm that I’ve never been able to imitate. He’s much more irregular than I am, and I don’t know where the rhythm comes from, but I admire it very much. Crane said somewhere that he could write five or six good lines but Tate could write twelve that would hang together, and you’d see how the twelve were built. Tate was somehow more of a model: he had a lot of wildness and he had a lot of construction.

Peter Taylor:

Allen Tate particularly made a great impression on me. I had him as my freshman English instructor at Southwestern and he was electrifying. He talked about the art of fiction, taking it seriously as a form. It was his genius as a teacher that he made young people feel the importance of literature, the importance of art. That came just at the right moment for me. I had already realized that I had a welter of stories I wished to tell. I had written stories, I had written poems, but I had no real principles of writing. When I became interested in the formal qualities, art and life itself meant something. Later in life, Allen Tate and I quarreled. I think he did me a great injury. But I was able to forgive him because that injury counted for almost nothing compared to what he taught me when I was young. The next summer I took a writing course with Tate, in fiction, and that was the real beginning. Allen liked my stories immensely. He wrote letters to Robert Penn Warren about them—at that time Warren and Cleanth Brooks were editing The Southern Review—and sent him two of my stories, without my knowledge. That was very like Tate. He was ever generous with young people, to the end of his life.

Another Evening Gone

If you never have, watch this 1964 episode of the BBC show Monitor, in which John Betjeman interviews Philip Larkin. It is twenty-four minutes well spent. There’s the poetry: Larkin reads “Here” and “A Study of Reading Habits” and “Toads Revisited” and “Church Going” and “Wants.” Betjeman inventories the wares of a Hull department store like a mystical incantation.

There's the deliberate portrait of Larkin's circumscribed existence: we see his flat, the cemeteries and streets where he walked, and of course, the library where he worked.

Betjeman was a great champion of The Whitsun Weddings, and his knowledge of and admiration for Larkin’s work is clear. The portrait is certainly what both poets would have wished, carefully orchestrated from its location to its doleful closing quotation. And yet, there is the great, odd moment when Betjeman says, “I envy you, being a librarian. It must be marvelous to have something to fall back on.”

Lawn Fawn Moon Boon

An illustration from Topsell’s The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents, 1658.

The excellent Public Domain Review is making its first foray into print with a new anthology, The Book of Selected Essays, 2011–2013, celebrating their three years as dedicated spelunkers of the public domain. They’ve amassed an incredible collection of esoterica—stuff that, as their editor Adam Green writes, “didn’t quite make the cut when that mysterious editor on high was working away with razor blade and glue upon the reels and reels of recorded past”—much of which I hadn’t encountered before. How, for instance, had I never heard of Christopher Smart?

Smart was an eighteenth-century English poet, an intimate of Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, and Henry Fielding; in 1755 he got a gig producing a weekly paper, The Universal Visitor or Monthly Memorialist, and the job so overworked him that he had some kind of a nervous fit. It’s not clear whether he really went mad or not, but he was admitted to St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics—an admirably blunt name, no?—where he wrote one of his more enduring works, Jubilate Agno.

As Frank Key writes in the Public Domain Review,

Smart never completed the work, which consists of four fragments making a total of over 1,200 lines, each beginning with the words “Let” or “For”. For example, Fragment A is all “Let”s, whereas in Fragment B the “Let”s and “For”s are paired, which may have been the intention for the entire work, modelled on antiphonal Hebrew poetry. References and allusions abound to Biblical (especially Old Testament) figures, plants and animals, gems, contemporary politics and science, the poet’s family and friends, even obituary lists in current periodicals. The language is full of puns, archaisms, coinages, and unfamiliar usages. Dr Johnson famously said “Nothing odd will do long; Tristram Shandy did not last.” Jubilate Agno is, if anything, “odder” than Sterne’s novel, and perhaps we are readier to appreciate it in the twenty-first century than when it was written.

Indeed we are. “One of the great joys of Jubilate Agno,” Key says, “is in its sudden dislocations and unexpected diversions.” Nowhere is this more evident than in the poem’s most famous passage, a long consideration of Smart’s cat, Jeoffry:

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For this is done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his forepaws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the forepaws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For tenthly he goes in quest of food.

Smart was known, with his “disturbed mental state,” for his loud, feverish, constant praying, and you can read some of that catatonia in Jubilate, with its litany of “for”s and its incantatory quality. Elsewhere, the poem is more openly religious: “For Eternity is like a grain of mustard as a growing body and improving spirit,” one line goes, “For the malignancy of fire is oweing to the Devil’s hiding of light, till it became visible darkness. ” And its vaguely apocalyptic consideration of music reads like an especially manic evangelical pamphlet, of the sort that glassy-eyed believers sometimes try to press into your hands on the subway:

For God has given us a language of monosyllables to prevent our clipping.

For a toad enjoys a finer prospect than another creature to compensate his lack.

Tho’ toad I am the object of man’s hate.

Yet better am I than a reprobate. who has the worst of prospects.

For there are stones, whose constituent particles are little toads.

For the spiritual musick is as follows.

For there is the thunder-stop, which is the voice of God direct.

For the rest of the stops are by their rhimes.

For the trumpet rhimes are sound bound, soar more and the like.

For the Shawm rhimes are lawn fawn moon boon and the like.

For the harp rhimes are sing ring string and the like.

For the cymbal rhimes are bell well toll soul and the like.

For the flute rhimes are tooth youth suit mute and the like.

For the dulcimer rhimes are grace place beat heat and the like.

For the Clarinet rhimes are clean seen and the like.

For the Bassoon rhimes are pass, class and the like. God be gracious to Baumgarden.

For the dulcimer are rather van fan and the like and grace place &c are of the bassoon.

For beat heat, weep peep &c are of the pipe.

For every word has its marrow in the English tongue for order and for delight.

You can read the completed fragments of Jubilate Agno in their entirety here; it’s one of roughly thirty texts given careful attention in the Public Domain Review’s book, which they’re offering at a reduced price through November 26.

Who Shot Van Gogh? and Other News

Toulouse-Lautrec’s portrait of Van Gogh, 1887.

Mark Twain’s career as an author began at a place called Jackass Hill, a boomtown gone bust where, in the local tavern, he heard the story that would become “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” “[I] turned my attention to seriously scribbling to excite the laughter of God’s creatures,” Twain wrote. “Poor, pitiful business!”

Today in terrifyingly ambiguous headlines: “Family’s agony over when to tell mother her premature babies died while she was in a coma after she woke up.”

“O to sail to sea in a ship!” Walt Whitman inspired many things—one of them, it turns out, was a logo.

Was Van Gogh … murdered? Conventional wisdom has it that he shot himself, but the facts don’t really support his suicide. “What kind of a person, no matter how unbalanced, tries to kill himself with a shot to the midsection? And then, rather than finish himself off with a second shot, staggers a mile back to his room in agonizing pain from a bullet in his belly?”

“I sometimes see science like art. People don’t necessarily see the connections to how it makes their lives better—this is not going to give them a better toaster, or something like that—but there is this feeling, just like with art, that this is important in some way. It is worth expending vital resources on, whether it’s tax money or people’s focus. It just feels worthwhile to do.” What we talk about when we talk about landing spacecrafts on comets.

November 18, 2014

Overheard Haiku

The rhythms of overheard speech.

Photo: NARA

In Martin Walser’s 1987 book Brandung, about a German professor teaching abroad at the very un-German University of California, Berkeley—a novel really not worth reading unless you are interested in German-English translation and able to read it in the Berkeley sun, to a whiff of eucalyptus or a glimpse of Mount Tamalpais, and even then I didn’t finish it—the professor overhears a bit of dialogue. A student steps into an elevator and says “Going up?”; the one in the elevator says “Trying to.” The professor, “who did after all teach English back home, was crushed to realize, yet again, that he would never master this language.” Not long afterward, he sees a campus newspaper headline, “Sex Blind Admission,” and tries and fails to reconstruct the line in German. “English is a language for headlines,” he thinks.

I saw a headline myself in Berkeley, on the unbelievably trashy San Francisco Examiner: “Cops Fear Pimp Turf War.” Five punchy syllables, each pretty much any part of speech—it took me a moment to understand what it meant, then I knew I had witnessed greatness. (I’m not the only one who noticed: a weekly DJ night called “Cops Fear Pimp Turf War!” sprang up a few months later in San Francisco.)

It was walking in downtown Manhattan, on the other hand, past the new construction of, according to the slogan around the scaffolding, TWENTY INDIVIDUALLY-CURATED FINELY-CRAFTED CONDOMINIUM RESIDENCES, that a couple hurried past and we heard the man say, “The problem is in this country people believe they deserve something ... ” Whether his complaint targeted the members of the 1 percent who were building or planning to live in these super-creative residences, or the passersby resenting that they couldn’t, or other groups altogether, it was also a classic example of American speech:

The problem is in

this country people believe

they deserve something

It’s not a haiku—the haiku form has demands besides 5-7-5 syllables: seasonal key words (kigo), one image, two moments with a turn or jump cut between them indicated by a “cutting word” (kireji). It’s the serendipitous, spoken, American form: the overheard haiku.

I’d heard about it from the poet Robert Hass, teaching a survey of American poetry course back at UC Berkeley and talking one day about speech rhythms. He mentioned something he’d overheard while in D.C. as Poet Laureate: a man in not a $1,200 overcoat but an $800 overcoat (midnineties dollars)—that means a lot, perhaps everything, in Washington—had said,

Well if he’d just been

focused he wouldn’t even

have considered it

After paying attention and counting syllables for not very long at all, you can hear this form everywhere. The length of a thought—in English? Or with average walking speeds? Or that you can remember when you’re not really listening?—seems naturally to fall into 5-7-5 syllables:

It’s just, right now I

don’t feel very much respect

for myself is all

She has a home phone.

Who has home phones?… Yeah different

lifestyle … Totally.

Or for that matter:

“Individually-

Curated Finely-Crafted

Residences”? Please.

Around half a tweet, but again, a very different form. “Cops Fear Pimp Turf War,” well less than a semi-demi-tweet, comes closer, because it is written: Twitter can share #overheardhaiku, but is not the medium for creating them.

English is a great language for writing headlines, and tweets, but also for hearing haiku. You can’t plan a phrase like this, craft it, present yourself to the world with it; it’s something you run across, something the facts of the world and of language fall into. As though by chance. It’s something you’ve trained your ear to notice, a way of paying attention.

Damion Searls, the Daily’s language columnist, is a translator from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch.

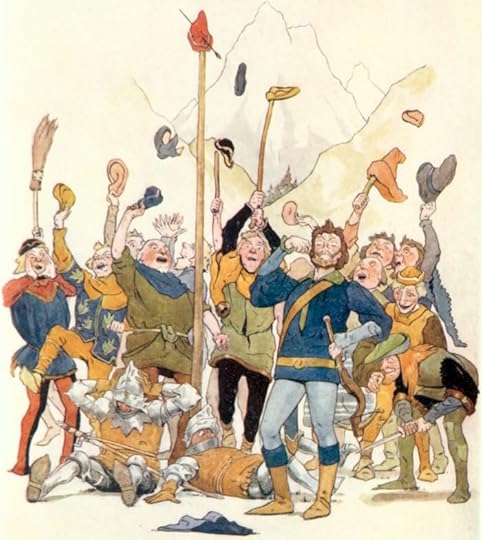

Them Apples

An illustration by Philip Dadd for P. G. Wodehouse’s William Tell Told Again, 1904.

According to legend, it was on November 18, 1307, that the Swiss patriot William Tell shot an apple off his son’s head. After refusing to pay homage to a Hapsburg liege, Tell was forced to submit to the test of marksmanship. Later, Tell killed the tyrant and went on to many a daring exploit in the service of the Old Swiss Confederacy.

Although the William Tell legend is mentioned in books dating back to the late fifteenth century—and one can find similar marksmanship myths throughout the world—it was Schiller’s highly politicized play that canonized the apple-centric version, and, buoyed by Switzerland’s post-Napoleonic patriotism, made the archer iconic. Schiller had never visited Switzerland; he got the idea from his friend Goethe, who returned from a trip bearing tales of local lore. In 1804, the play premiered at Weimar under Goethe’s direction. (The popular Rossini opera—and the resulting Lone Ranger theme—was based on the play.)

Although a part of the German dramatic canon (and initially a Nazi favorite), the play came into disfavor with Hitler. After a 1941 assassination attempt by a Swiss-born activist, the Führer banned William Tell, reportedly lamenting, “Of all people Schiller had to glorify this Swiss sniper.”

I would say Tell is well remembered, but lately I’ve been very concerned. As readers of tabloids well know, the reality-star-turned-Pinterest-doyenne Lauren Conrad recently married a law student and former musician (Wikipedia’s words; I would have thought you sort of kept amateur status throughout life) named William Tell.

Now, one would think that the name William Tell would be a great boon. Every Halloween costume, every birthday-party motif, every college-admissions essay writes itself. At the very least, one would imagine that such a name would give rise to a little apple-related badinage when the man in question became engaged to a bold-faced name. But no. Nary a bow and arrow decorated their wedding bower; nary a Schiller quote graced the pages of Us Weekly. It’s bad enough that the actress Anne Hathaway should have superceded Shakespeare’s wife in the public consciousness; now Lauren Conrad’s husband is hard on the Swiss patriot’s heels in Google results. As Schiller said, “Against stupidity the very gods themselves contend in vain.”

Notes on Vape

Photo: Jon Williams, via Flickr

Last night, Oxford Dictionaries announced its Word of the Year—vape—and it was hard not to feel, at first, a twinge of disappointment. After all, 2013’s Word of the Year was selfie, which was so ubiquitous, so contentious, so undeniably germane to our times, that think pieces are still being written about it a year later. Selfie was a gift from the lexical gods, a soft disyllable that contained within it the whole winding story of our evolving relationship with technology. Choosing it was almost an act of synecdoche: it stood for a massive and increasingly vexed conversation about our lives online.

But our neology isn’t always so supple; Oxford Dictionaries is on the lookout for words that “reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year,” and not every year delivers a pluperfect sign of the times. You play the hand you’re dealt. And 2014 has dealt us a lot of duds—slacktivism, budtender, bae, and normcore were on the shortlist this year, all clever and evocative as far as they go, but none of them with that era-encapsulating magic.

And none of them with the guarantee of longevity. I asked Allison Wright, an editor at Oxford University Press, what she and her colleagues look for in the Word of the Year, and she emphasized the importance of finding a word that isn’t “a flash in the pan.” Hence, she said, the ultimate appeal of vape—(v.) inhale and exhale the vapor produced by an electronic cigarette or similar device; (n.) an electronic cigarette or similar device; an act of inhaling and exhaling the vapor produced by an electronic cigarette or similar device—which promises to be around for a little while.

“It’s generating a new and more productive vocabulary,” Allison told me. I hadn’t been sold on vape until I considered the ramifications of this vocabulary, around which an entire subculture has risen. Oxford’s announcement calls out vape pen, vaporium, and most notably the retronym tobacco cigarette, which signals vape’s influence: what would’ve been laughably redundant in the twentieth century is now a necessary distinction.

I remember the first time I encountered an e-cigarette, probably five or six years ago, in my early twenties—not a time when you want to sense that the world’s moving too fast for you. That’s how I felt, though: Here was this sleek black cylinder with a blue light that throbbed when I inhaled from it. You could charge it with your computer. You could buy it from a kiosk in the mall, and yet I had no idea how it worked. Here was a harbinger of my obsolescence: I could see how in a few decades’ time the latest technology would overshadow my abilities to grasp it. I would grow old in the eclipse, ceasing to live in the present. Also, the spearmint flavor was really good.

And the need for the word—what Oxford refers to as “a gap in the lexicon”—was certainly there. I can recall a brief period in which people spoke of e-cigging and e-smokers, but these words always came tissue-wrapped in scare quotes, a shroud of irony marking their uncertainty. What we were reaching for, and soon found, was vape, a handsome abbreviation of vaporize. As a derivative of vapor, it’s a spin-off of a kind of heritage brand. For a word that just means “a substance diffused in air,” vapor has taken on a rich figurative life over the years—you can get the vapors, you can be vapid, and (best but most rare of all) you can vapor on and on—“to indulge in bragging, blustering, or idle talk,” as Merriam-Webster defines vapor the verb, with a perfect example: “a faded Southern belle tiresomely vaporing about all the handsome beaux she had in her long-ago youth.” So vape partakes of a long history of things turning mysteriously or irksomely into air; it won’t be long until someone puts it to apt figurative use.

Selfie asked us to accept what was, for some, a hard truth: that we live in an age when we really like to photograph ourselves, mainly because we’re better equipped than ever to do so. Vape is similarly pitched between hedonism and futurism. It celebrates something humans have always excelled at, which is finding new and novel ways to get buzzed. If neither of these words makes a rah-rah case for our enlightenment, so what? Where conservative critics see a culture dedicated to narcissism and addicted to nicotine, I see a bunch of people trying to have a good time—and a pair of words taking a small stand against propriety.

Advanced Studies in Time Wasting, and Other News

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Symposium, 1894.

The Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year is vape , which can function as a noun or a verb and “arose to fill a gap in our lexicon.” One can only imagine all the e-cigarette manufacturers presently scrambling to send complimentary samples to Oxford University Press’s offices.

At last, someone’s teaching a course at the University of Pennsylvania called “Wasting Time on the Internet.” “Although we’ll all be in the same room, our communication will happen exclusively through chat rooms and listservs, or over social media. Distraction and split attention will be mandatory. So will aimless drifting and intuitive surfing.” I’ve been auditing this class unknowingly for my entire adult life. I must owe UPenn hundreds of thousands of dollars by now.

Today in algorithms: a new one “automatically generates an independent ranking of notable authors for a given year.” It’s intended to help archivists learn which books in the public domain were the most popular—but it also has huge ramifications for ego massage and ego damage.

“He leans his right elbow on several grapefruit-size balls he has made from rubber bands people have given him during his daily circuit of social pit stops in Manhattan. He keeps hard candy in his pockets and a box of dog biscuits in the trunk, for dispensing.” This is New York’s oldest cabbie.

The oldest leather shoe, by comparison, has been around for 5,500 years and can be seen at a museum in Armenia.

November 17, 2014

Let’s All Go Down to the Bridge and Get Our Teeth Pulled

Louis-Leopold Boilly, 1827.

I’ve been enjoying The Smile Revolution, Colin Jones’s trenchant, very readable history of the smile—specifically its evolution in eighteenth-century Paris, where smiling was once, as the jacket copy puts it, “quite literally frowned upon.”

Obviously the emergence of the smile owes plenty to the emergence of dentistry, but the story as Jones tells it owes as much to shifting social mores as it does to science—and much of the fun in The Smile Revolution is in reading about this cultural shift. Here, for a taste, is the story of Le Grand Thomas, a charlatan who made a career of yanking people’s teeth out. Apparently you could find him standing on the bridge every day, barking and hawking his talents, dressed in a baggy scarlet coat. He traveled with a pair of musicians and a large cart with an enormous tooth (“Gargantua’s awesome molar”) hanging from it. Here’s Jones:

Every day, from sometime in the 1710s until his death in 1757, Jean Thomas stood on the Pont-Neuf, alongside the cheval de bronze … and offered to pull out the teeth of all and sundry.

[…] His portrait proudly proclaimed:

Our Grand Thomas, beplumed in glory,

The Pearl of Charlatans (or so’s the story).

Your Tooth aches? You need never doubt

Le Grand Thomas will yank it out.

[…] The demeanor of le Grand Thomas was such that it seemed that he could terrify peccant teeth into submission. Everything about him exuded mythic power. The medicines he described were made up in doses suitable as much for a horse as a man. He himself weighed the same as three men, and ate and drank for four. His barking voice could be heard across the city. If a client’s tooth resisted his assaults he would, it was said, make the individual kneel down in front of him and then, with the strength of a bull, lift him three times into the air with the hand still clenched on the recalcitrant tooth.

Le Grand Thomas was no mere physician—he was a folk hero. In 1743, toward the peak of his massive popularity, there was a character based on him in a play called Le Vaudeville. A few of his lines:

Beware the lure of windy exaggeration

Which doctors use—for our assassination.

Tho’ I, Thomas, am tongue-tied in truth

At least I can help with the ache of a tooth.

I pull it right from the root.

Crack! Right from the root.

In all my years of dental, orthodontic, and periodontal care—years of care that, don’t get me wrong, I’m quite grateful for—I’ve never encountered a figure with such panache.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers