The Paris Review's Blog, page 641

November 23, 2014

This Week on the Daily

Georgios Jakobides, Girl Reading, ca. 1882, oil on canvas.

Never-before-heard recordings of Maya Angelou, Denise Levertov, and Gary Snyder from our ongoing collaboration with 92Y.

*

Why has Italian cinema lost its appeal abroad? Antonio Monda sees a pattern: “The films that speak to a world audience deliver a poetic or extreme image of Italy, or of an ‘Italy,’ that gibes with the image foreigners already have of it.”

*

Lilly Lampe reviews “Teen Paranormal Romance,” a group exhibition inspired by the burgeoning genre of YA lit.

*

Damion Searls hears haiku in the rhythms of American speech.

*

A brief history of insect control: James McWilliams tells the surprisingly fascinating story of how pesticides came to dominate American agriculture.

*

Plus, Sadie Stein on migraines, “the most glamorous of headaches”; some thoughts on vape, the OED’s 2014 Word of the Year; and Duane Hanson’s Security Guard patrols an art gallery in terrifying solitude.

November 21, 2014

Staff Picks: Staircases, Sister Mountains, Self-Help

A still from The Staircase.

In The Program Era, Mark McGurl illuminated postwar American fiction’s inextricable ties to universities and creative-writing programs; his new paper, “The Institution of Nothing,” undertakes a reading of David Foster Wallace in the framework of “the program,” and it’s one of the most thoughtful exegeses I’ve found of Wallace, whose work has enjoyed no shortage of critical insight. (Remember Wyatt Mason on Oblivion?) McGurl finds that the bulk of Wallace’s writing is fixated on institutions—it invokes them as a kind of safe harbor, a respite from the nihilism of the world at large. (This is borne out not just in his books but in his life, which he spent almost entirely in the thrall of institutions of higher learning.) In this light, a certain unnerving conservatism emerges in his work: what should be questions of sweeping political import are recast as matters of individual ethics. McGurl writes, “Clinging to the institutional order, clinging for dear life, Wallace’s commitment is … to a conception of therapeutic community in which what might have become political questions—and, by implication, motives for political contestation—are obediently dissolved.” —Dan Piepenbring

Natalie Lyalin’s poetry collection Blood Makes Me Faint But I Go For It has an intriguing title, but I’ve felt mildly daunted by the illustration on the cover—of a woman who stares straight into my eyes whenever I look at her. It turns out, though, that such feelings of discomfort aren’t inappropriate. Lyalin’s poems are weird, wide-eyed, and bold, and I feel uneasy reading them—in a good way. Like this, from “On the Beaches of Majorca”: “Aboard ships they snapped goodbye to their cities / They sparked like knives / And the oceans took them in with oceanic slurps / In a parallel moment we were on the beaches / Mute pastel puffs / Smoking around a cult-like fire.” Her poems remind me of Karen Russell’s fiction: at once familiar and otherworldly, tame and frightening. Lyalin’s “A Lemon Sweat Over Everything” is almost a poetic version of the title story from Russell’s Vampire in the Lemon Grove:

You can find my bones in the sister mountains

Identify me by the gold fangs

The fangs I showed you in the lemon arc hard

almost two hundred years ago

You said they were sexy

The sun blinding you for my mouth

We were both smirking and then I snarled

It was very foreign

chasing you around the trees

—Nicole Rudick

I could write about the addictive nature of Serial, the true-crime podcast from the This American Life team, but millions of others beat me to the punch. Instead, thanks to a recommendation from my friend Josh Lieberman, I advise you to fill these next two weeks until the next Serial episode with Sundance Channel’s eight-part documentary series, The Staircase. The crime saga follows the case of the novelist Michael Peterson, whose wife, Kathleen, was found unconscious at the bottom of a staircase in the couple’s Durham mansion. Was the death an accident, the result of falling down the stairs after consuming alcohol and Valium—or was she murdered by Peterson? While the twists and turns are captivating and the series is filled with a cast of characters so interesting and bizarre it’s difficult to appraise anyone involved, it’s the fly-on-the wall–style of Jean-Xavier de Lestrande’s filmmaking that kept me going from one episode to the next. —Justin Alvarez

You might have heard that Sam Lipsyte used to be in a punk band called Dungbeetle. This Saturday night at Le Poisson Rouge, they’re reuniting—with LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy on drums, no less—as part of the launch party for Radio Silence, a lit-and-music mag that’s just released its third issue. I suspect magic will be in the air. Bring earplugs and a taste for the bizarre. —DP

I had never heard of Lorrie Moore when I tried to sit in on her M.F.A. workshop at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. It was 2009, and I was barely eighteen. She kicked me out pretty quickly. Now, having spent the better part of five years recovering from the embarrassment, I have finally read Self-Help, Moore’s first collection of stories. About two-thirds are written in the second person, and this is both refreshing and compelling. It serves an almost didactic purpose in “How,” as Moore guides us, step-by-step, through the motions of dumping a (maybe) dying boyfriend. In “How To Be an Other Woman,” the second person puts a delightful twist on a recycled story: her protagonist struggles to find herself in (and as a result of) a messy extramarital affair. Witty and deft, Moore demands that her readers believe the story could be about them … not that it is about them, but that it could be. She blends comedy and tragedy so seamlessly that I found myself merrily caught between sadness and mirth, cynicism and optimism. —Alex Celia

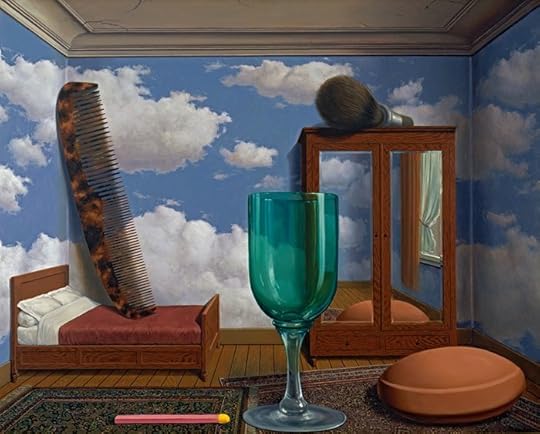

Magritte Shaving

René Magritte, Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values), 1952, oil on canvas. Image via SFMOMA

René Magritte was born on this day in 1898. Louis Simpson’s poem “Magritte Shaving” appeared in our twenty-fifth anniversary issue in Spring 1981.

The houses look at one another,

a language of windows.

The violin stands above the collar ...

sleigh bells in a blue sky.

How calm the torso of a woman

like a naked statue.

Reclining in an alcove

with curtains, the window gives

a view of earth ... yellow fields.

She has a blue leg and a green arm,

red arm, and leg painted saffron.

The orange sphere floating in space

in front of the blue canyon

has a face like a mask

with fixed brown eyes.

Directly underneath, on the parapet,

stands a shirt with a tie

in a dark, formal suit.

He has left his shaving brush

on top of the cabinet with doors of glass

that is merging with a cloud.

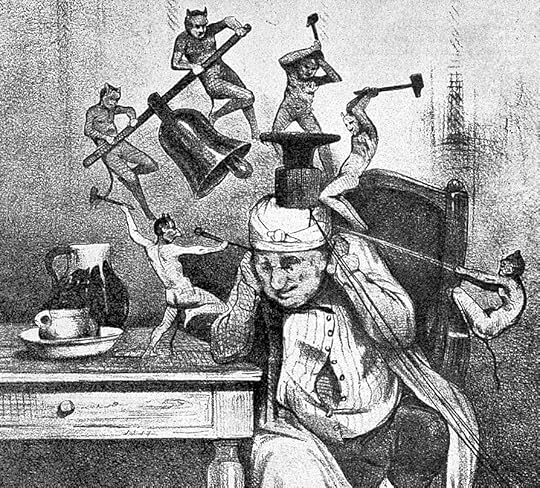

Head Cases

An illustration from Les gens de Medecine dans l'oeuvre de Daumier. Via the Wellcome Library

Migraines are the most glamorous of headaches. Mysterious, debilitating, unpredictable: they get all the press. Who wants to talk about the workaday irritation of a tension headache, the dull thud of dehydration, the queasy slosh of sinus infections? That’s not sexy. By definition, even; the headache is the punch line to half the Andy Capp jokes in the world.

But migraines! Everyone relishes a migraine. They have a literal aura! Migraines foster the sort of pure narcissism that only intense, essentially benign pain can. We sufferers (that’s how it’s described, “migraine sufferer”) feel it is meet and right that the migraine should be dramatized in films like Pi or White Heat; this strengthens the perception that migraines are the hallmark of geniuses, or at least psychopaths. Joan Didion writes about them; of course she does. In “In Bed,” she describes the purification arising from this crucible of pain:

The migraine has acted as a circuit breaker, and the fuses have emerged intact. There is a pleasant convalescent euphoria. I open the windows and feel the air, eat gratefully, sleep well. I notice the particular nature of a flower in a glass on the stair landing. I count my blessings.

Yes, Joan, yes! That’s it exactly! Of course, she also says, “My husband also has migraine, which is unfortunate for him but fortunate for me: perhaps nothing so tends to prolong an attack as the accusing eye of someone who has never had a headache.” I disagree. What migraine sufferer wants to share the limelight? After all, we all know in our hearts that no one in the history of the world has ever experienced basically unserious pain like we have.

It’s a bit like cats on social media. On the face of it, social media is a boon for cat fanciers, so long isolated from the easy socialization of other pet owners. And on the face of it, it is indeed a vibrant online community. But the suspicion cannot help but intrude, first, that everyone really thinks her cat is the cutest, the wackiest, the wittiest, the best. And second, that this conviction is unshakeable.

So it is with migraine sufferers. On the face of it, we’re collegial. Oh, you get migraines, too? We compare triggers (Tyramines? Blood sugar? Hormones?) and triptans. Have you tried Zomig? Maxalt? Imitrex? What about the spray? And then the one-upsmanship begins. How often? For how long? Where is your pain localized? Really, behind the eyes? Interesting. I didn't realize that qualified as a migraine! Light sensitivity? Nausea? Have you tried biofeedback? Beta-Blockers? Botox? Acupuncture? Going GF? (That’s recent.) What about that codeine stuff you can only get in Europe because the FDA hasn’t approved it? Have you been to the ER? How many times? Have you seen a neurologist? (We all have; there’s never anything wrong with us. At least, nothing detectable.) Of course, if anyone plays the “Cluster Headache” card, the conversation is over, and the rest of us have to trudge sullenly away.

Lost in Translation

Why has Italian cinema lost its appeal abroad?

A still from La grande bellezza, 2013.

It must be the Ponentino—the wind from the sea—blowing through the baroque gardens, or the scent of the Roman pines rising from ruins, but each time I return to Italy, I realize how much I miss its decadence. Yes, it’s this breeze, fresh yet melancholic, that makes me think of the persistent sense of fallacy in the eternal city. And while I can’t escape being mesmerized by Rome’s beauty, I question why contemporary Italian culture doesn’t travel or translate. It is as if Italy is appreciated only for what it was and not for what it has become.

While I appreciate the current popularity of Scandinavian literature, or the enthusiasm, periodically revived, for Latin American writers, I have to wonder why, or, indeed, if, Italian authors are less interesting to the Anglo-Saxon public than those spare, gritty Northerners and quixotic Latinos. Italy has produced a few celebrated authors, but there has never been a real fascination for our literature.

Cinema is a different story, perhaps because of its more immediate seductive power of images. La Dolce Vita was unique in making Romans feel that we lived, at least vicariously, in the caput mundi—the capital of the world. The film is the portrait of an Inferno costumed as a Paradise. Its glamorous description of Roman decadence generated a fashion, and people all over the world dreamed of enjoying those orgies, dressing in those stylish suits, driving those convertibles, listening to that music, and bathing in the Fountain of Trevi. As one character says, “to live within the harmony of perfect beauty.” Who wouldn’t subscribe to that fantasy? I would be the first, if I could ignore the fact that the intellectual who delivers the line commits suicide after killing his own children.

Federico Fellini has captured the city’s paradoxes—its wisdom and disenchantment, provinciality and universalism, morbid religiosity and virulent secularism—better than any artist before or since. And he did it again with Roma, Toby Dammit, and Satyricon, a science-fiction film set in a desperate, godless past. Since the heyday of neorealism, some of our best films have dealt with the same phenomena of glorious corruption and placid surrender to dissolution. It happened last year with La grande bellezza, directed by Paolo Sorrentino, a homage to Fellini, and la grande eccezione—the great exception in an otherwise fairly desolate artistic landscape.

* * *

After the seventies, Italy’s international artistic presence became marginalized, if not irrelevant. On my visits to Rome, I’m fascinated by the large number of posters advertising films that could never succeed abroad. Most of these pictures, and their directors, even seem indifferent to such an opportunity: they are self-referential, preaching to the choir. (Insularity has always been an Italian vice.) Other films suffer from the opposite form of provincialism: they are made with the international market in mind, sometimes with foreign actors and locations, yet without understanding how to penetrate it. The only director who’s been able to do it is Bernardo Bertolucci, but there’s a clear difference between the art-house success of the Italian The Conformist and the international, multiple-Oscar-winning The Last Emperor. You might think of Sergio Leone as well, but his hyperrealist, ironic celebration of American mythology was a case of its own.

Historically, the few Italian films that traveled well have been those deeply rooted in our culture while touching upon universal themes. In addition to La dolce vita and many other Fellini pictures, think of Divorce Italian Style, the Wertmüller films of the seventies and, more recently, Nuovo Cinema Paradiso and Il postino.

Except for Life Is Beautiful, a special case for its controversial treatment of the Holocaust, you might see a pattern: the films that speak to a world audience deliver a poetic or extreme image of Italy, or of an “Italy,” that gibes with the image foreigners already have of it.

* * *

Is exaggeration also the secret of La grande bellezza? In Paolo Sorrentino’s film, the description of contemporary debauchery is even more Roman—ancient Roman—than in La dolce vita. But the luminous beauty is still there, and, starting from the title, to the closing credits filmed along the Tiber, the movie expresses a continuous, hungry, even insatiable longing for its redemptive powers.

Both films show the pivotal presence of the Catholic Church: empires have fallen, art has evolved, and politics continue to disappoint, but it seems that the Church, despite its continuous mistakes, is the only institution that keeps dealing with the possibility of eternity. And both pictures embody that terrifying description of the city, which Marcello Rubini—Mastroianni plays a character with his own name—relays in La dolce vita: “a sweet swamp in which it is beautiful to drown.”

Fellini’s and Sorrentino’s films generated great controversy in Italy, where each met a critical coldness that was later annihilated by their international triumph. Italians don’t like to look at themselves in the mirror—especially, perhaps, the Italians who belong to the haute bourgeoise intellectual milieu the films depict.

But if you compare these films with other Italian hits, you’ll see it’s clearly not only beauty that wins the hearts of foreign audiences. The public abroad likes, on one hand, flamboyant Italian characters (such as those in the comedies of Germi and Wertmüller, or in dramas like La strada), and, on the other, melancholic and retro fables about children or poets (Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, Il postino).

When I speak about the failure of Italian films to translate, I’m not only referring to the work of auteurs beloved by a fairly esoteric circle of scholars and cinephiles. An excellent picture like Gomorra, for example—based on an international best seller and the winner of the Special Jury Prize in Cannes—did poorly at the U.S. box office: it shows the worse of Italy with neither a clear plot nor the possibility of redemption. The protagonists imitate Scarface and the mobsters from Goodfellas, but we hardly understand their names or their motivations, and we witness only the violent squalor of their lives. The Godfather, to mention a huge hit in gangster genre, had a completely different approach: The ultimate Italian-American film was a celebration of a criminal family, where family, deeply rooted in the Italian archetype, prevails over criminality. The Corleones perform horrible acts while delivering unforgettable lines, and the audience is forced to realize that in the saga no one is morally superior to them.

Moral ambiguity, or worse, seems to be another winning card: for the foreign audience, it confirms preexisting impressions or prejudices. But it needs memorable characters and a strong narrative arc. Within the moral territory, nothing appeals more than l’arte di arrangiarsi, the art of making do, the quintessential Italian way of solving problems in creative, smart, often anarchic, and not necessarily ethical ways. This seems to have disappeared: Where is the Baron Cefalù of Divorce Italian Style, the man who falls in love with an adolescent cousin and creates the most byzantine way to possess her after killing his wife? Has a more creative way ever existed of explaining the expression getting away with murder? Did you ever meet anyone in the audience who wouldn’t root for him? Sure, it’s almost impossible to dislike Marcello Mastroianni, and in the film the cousin is much younger, lighter, thinner, and sexier than the wife—but Germi’s genius manipulation makes us minimize, if not ignore, the monstrous moral of the story. This triumph of amorality in the country of the Catholic Church is another Italian paradox, which ends up being hugely attractive for its cunning fooling of legal and religious institutions.

A still from Divorce Italian Style, 1961.

In most of today’s cinema, we are very far from this kind of ruthless freedom: what we see is a universe of bitter, conformist, pompous self-consciousness, designed, it seems, as a vehicle for some lugubrious message.

Art always reflects the circumstances under which it is created, and in the last twenty-five years, the majority of Italian filmmakers have been focused on representing an economical, social, and political crisis that seems still distant from being solved. Or, worse, complaining about it, without the creative leap that would seduce an international audience. It’s not simply a matter of talent, but of culture, courage, vision. If the international audience tends to enjoy clichés about Italy, we seem to have lost the truth behind those stereotypes without being able to replace them with anything exciting, nonideological and noninsular.

Our neorealist masters narrated a much greater crisis through powerful pictures that were never contaminated by a “message.” The solidarity and hope we found among the postwar ruins have been replaced today by depression and indignation.

Honestly, I don’t see why an international audience should enjoy this, why it should embrace seriousness versus freedom and beauty. Maybe the public abroad resists our proposals because they love us too much, they don’t want us to betray our spirit—to become a joyless, moralistic people.

So the Ponentino continues to blow against the posters for films with no international future. I feel that this crisis might be solved only through the arte di arrangiarsi. The foreign audience misses and loves our decadence as much as I do. I recall a line from Ennio Flaiano, who wrote La Dolce Vita with Fellini: “In Italy the situation is always tragic, but never serious.”

Antonio Monda is the author of nine books, including, most recently, La casa sulla roccia. His work has been translated into eleven languages. A regular contributor to the cultural page of La Repubblica, and a columnist for RAI Italian Television and Vogue Italy, Monda has directed several documentaries as well as the feature film Dicembre. He lives in New York, where he teaches in the Film and Television Department at New York University.

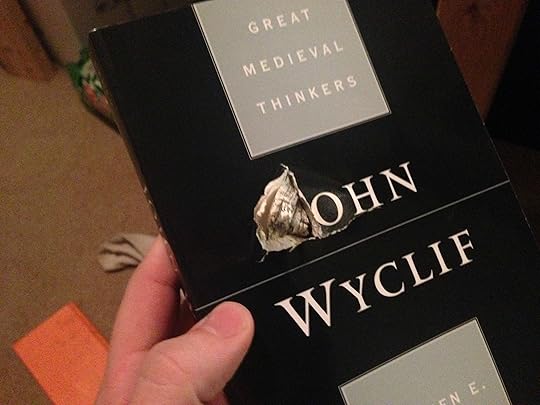

Books Stop Bullets, and Other News

Photo via Reddit

At Florida State University, a student’s life was saved when the books in his backpack stopped a bullet. (Insert joke about e-books, importance of print here.)

On Boston’s David R. Godine, a publisher who “specializes in books nobody buys … Godine has a knack for nurturing Nobel Prize recipients; he was the first in the United States to publish Modiano as well as 2008 Nobel laureate J. M. G. Le Clézio. He is renowned for producing—if not always selling—eclectic and fastidiously assembled and designed books.”

“Like eros, wonder was once considered a dangerous passion. Much of the traditional intellectual ambivalence surrounding wonder derived from its affinity to the passions of horror and terror … Modern wonder, like many of the traditional passions, has faded from the saturated hues of blood red and lapis lazuli blue to baby pink and blue pastels. ‘Baby’ is used advisedly in this context: modern wonder has become infantilized, the stuff of children’s entertainment, whether in the form of cartoon fairy tales or science museum exhibitions.”

The first-ever weather forecast, from 1861: “North—Moderate westerly wind; fine. West—Moderate south-westerly; fine. South—Fresh westerly; fine.” (It was mostly accurate.)

… And today there are, apparently, commercial meteorologists, who “work behind the scenes to provide companies with customized weather data and analysis. On some days, like last Wednesday, that can entail cooling unfounded fears, while on others it means assisting corporate clients in prepping for a natural disaster. Whatever the weather throws at stores and shoppers, it’s the job of commercial meteorologists to help stores and their emergency management teams put a plan in place.” (Leaving their customers to make do with good old network-television meteorologists.)

November 20, 2014

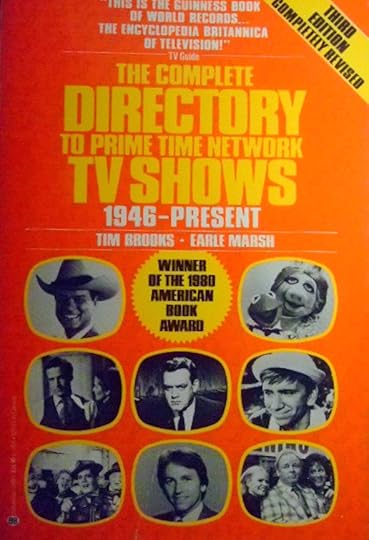

Winner of the American Book Award

The third edition of The Complete Directory, prominently advertising its award-winning status.

The early eighties were strange times for the National Book Award. At the turn of the decade, the award’s custodians decided to modernize its image. As Craig Fehrman described the scenario in The New York Times a few years ago, “If publishers were going to spend upward of $100,000 a year running the prizes—not to mention the costs of transporting and feting authors—they wanted something that would give them a better return on their investment.”

And so the National Book Awards—which were, at the time, frankly even more literary than they are today—were dissolved. In their stead came the American Book Awards, a wan bid for populist affection, as implied by that patriotic new name. “It will be run almost exactly the way the Academy Awards are run,” a spokesman told reporters, as if the fickle literary set were hankering for an injection of Hollywood glamor. Or Broadway glamor—a theatre producer designed the set for the event, which was to be televised. An “academy” of more than two thousand publishing pros took part in the voting.

In 1979, awards were given in seven categories. In 1980, they were given in twenty-eight, including typographical design, current-interest nonfiction, religion and inspiration, and—my personal favorite—general reference. In essence, the American Book Awards are to the National Book Awards as New Coke is to Coca-Cola Classic, i.e., a complete fucking disaster, one that all parties involved would prefer to forget.

But we shouldn’t forget, especially not now, the day after the National Book Award’s latest crop of winners has been announced. The American Book Awards serve as a reminder that ostensibly prestigious institutions—institutions whose authority and taste depend on their perceived stability—are just as susceptible to whims and trends as the rest of us, which is to say very.

I have a kinder point to make, though, which is that some of those American Book Award winners are actually very good at what they do. Take 1980’s general reference winner, Tim Brooks’s and Earle Marsh’s The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network TV Shows, 1946–Present. I have to say, having spent several hours with its ninth edition (ca. 2007), that it’s a charming, gracefully written, and incredibly handy reference text, one that’s easily more broadening for the mind, and more fun to read, than some of the fiction to have won the National Book Award in recent years.

Like a lot of once-vital reference books, the Complete Directory’s purpose has been lately obviated by the Internet, that completest of directories. In the thoughtful compression of its writing, though, and the scope of its research, it argues for life beyond Wikipedia, which for all its comprehensiveness doesn’t include a lot of the TV shows mentioned in this book—and when it does, its writing on them isn’t nearly as smart. The Complete Directory does what all good reference books do: it gives readers a sense of the immense vastness of its subject, an easy way of accessing information on the specifics of that subject, and the chance to discover—by a happenstance that always feels magical in this sort of text—stuff that we never knew.

Most of the Directory’s bulk is devoted to capsule reviews of … well, every American network television show of all time. Its back matter includes primetime schedules for all the major networks spanning several decades, a kind of nostalgists’ TV Guide. What did CBS air at 9:30 p.m. on Mondays in Fall 1952, for instance? I’ll tell you. Hang on.

It was Life with Luigi. (“Luigi was a newly arrived Italian immigrant who was learning to love his new homeland. He did no always understand what everything meant, and often took things too literally…”)

You can understand, then, why it won an award. It’s a series undertaking, a big old body of facts, and I imagine there was a time when it could be found on the shelves of any media studies professor, or on the coffee tables of any self-styled TV mavens, or maybe dog-eared in some network exec’s summer home.

Here are samples from three of its fluent, often wryly funny descriptions, all pertaining to old shows I’d never heard of.

Kobb’s Korner (CBS, 1948-49):

The Korn Kobblers were a group of accomplished musicians who, in addition to playing straight music, used mouth harps, whistles, sirens, cowbells, jugs, washboards, and anything else would at would make a noise. Actress Hope Emerson played Maw Shufflebottom, the other of the general store, and Jo Hurt played her daughter Josiebelle.

Break the Bank (ABC/NBC, 1948-57)

Experts’ were brought in to answer complex question worth thousands of dollars. They did this while standing in a specially designed ‘Hall of Knowledge’ … Among the unusual contestants during this period were two Hungarian refugees just arrived in the United States (their category was ‘Fight for Freedom’) and the veteran actress-singer Ethel Waters, who said she needed the money to pay off back taxes (she won $10,000).

The Borden Show (NBC, 1947)

It opened outside the club with a shot of a group of autograph-seekers besieging an unseen celebrity—who turned out to be Elsie the Borden Cow, in marionette form. The camera then moved inside where emcee Wally Boag entertained with his rubber balloons.

Read enough of these and apposite phrases start to leap out at you—you’re steeped in a kind of dream vision of Americana, rife with stereotypes and easy laughs and the unnerving comforts of the overfamiliar—

Dagmar, the statuesque, well-endowed blonde … starred in this late-night variety show as the hostess of a real canteen for servicemen

An intelligent, dreamy boy whose great passion was bicycle racing

Rusty was incredibly gullible and constantly falling in love

Sonny and Will were two gypsy truck drivers from radically different backgrounds

Mayor Alcala was no youngster, having been in office for sixteen years

Only Gerald B. Hannahan, the balding, bombastic regional director of CIS, linked him with the world of spies and adventure

As we’ve written about before on the Daily, it’s hard not to miss these sorts of books, these hulking compendia with their claims to the definitive. The Complete Directory’s ninth edition still bears a small reminder of its past as a National Book Awards anomaly—AMERICAN BOOK AWARD WINNER!, says a small, many-pointed star on the backside. This in 2007, when the AMAs were more than twenty years gone. I like that lack of qualifications. There’s no asterisk to explain that the American Book Awards no longer exist; or that they do exist, kind of, just under a different and much more highly regarded name; or that they were eliminated in just a few years because people hated them. It just states the truth: this book won a major award.

Call Me Madam

Photo: Karen Horton

In my defense, I was really little when my mom took me to my first concert at a grown-up concert hall. The music was for children, but I was still too babyish; I demanded to leave in the middle of act I so I could pee. I have no memory of what we heard that day, but the elegant bathroom made a huge impression on me. “Who was that lady?” I asked my mother, after a uniformed woman had handed me a paper towel and my mom had dropped a bill in her basket. And she explained: that was a Madame Pipi.

For a long while after that, I was obsessed. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” adults would ask me. And I would answer, “A Madame Pipi.” It seemed to me the most glamorous job in the world; to be surrounded by grandeur, dressed in a smart uniform, and have a bowl of money, besides. To a small child, all grown-ups seem important and magisterial; bathrooms loom large; the adult measures of income and status do not apply. I made myself a Madame Pipi outfit with a small apron, although my parents would not allow me to be on duty when we had guests.

Nowadays, bathroom matrons are less figures of fantasy than of controversy. Recently Keith McNally removed the attendants from Balthazar after patrons complained that the practice was extortionate and made them uncomfortable. It’s true that in modern times the meaning of the job has changed. When the legendary Lorenzo Robinson died after years working as a bathroom attendant at the Twenty-One Club, it was regarded as the end of an era. (His words: “When I leave, it’s going to be an end of an era.”)

And whereas a hundred years ago a lady at a ball might well have needed a quick stitch to a hem or a gentleman might have wanted his tails brushed down, now their role is less clear. “It makes me feel like I’m the kind of guy who dreams of being rich enough to be able to pay someone to turn on the water for me,” Henry Blodget wrote in Business Insider, criticizing Balthazar’s attendants. McNally wrote at the time of the attendants’ reassignment that, although he loved these employees, “I’m looking forward to standing at Balthazar’s urinal without another man staring at me.” (By contrast, a colleague said of Robinson, “He made it so once you met him, you wanted to come back to talk.”)

Of course, in other countries the whole matter is less fraught. It’s far more common in Europe to find a bathroom attendant, often one whose job is to accept a small fee in order to use the facilities. But even there, it is an endangered phenomenon. Yesterday was (apparently) World Toilet Day, and one blogger took to his keyboard to salute the Madame Pipi, and to lament her passing.

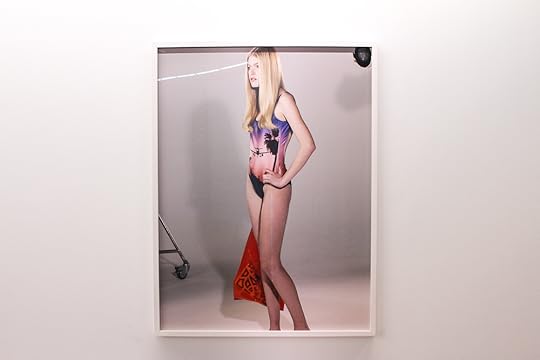

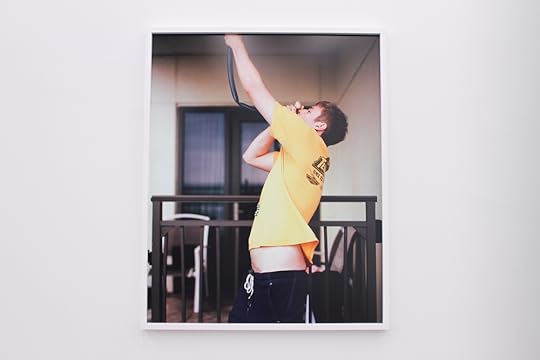

Teen Paranormal Romance

Finding artistic inspiration in YA lit.

Roe Ethridge, Louise with Red Bag, 2011, chromogenic print in artist frame, 69" x 52.5". Collection of Daryl and Irwin Simon. Photo: Kimberly Binns

At the behest of his preteen daughter, Hamza Walker set off one Saturday in search of Insurgent, the second book in Veronica Roth’s wildly popular Divergent trilogy. The book had been published the day before, and early crowds had snapped up seemingly every copy in Chicago. After a fruitless trip to Powell’s, Walker tried Barnes & Noble, only to be turned away. With his daughter’s imprecations buzzing in one ear, he stared at the Insurgent-less bookshelves, noting their panoply of shockingly similar titles. Then he saw the label on the wall: TEEN PARANORMAL ROMANCE.

Those three disparate words rang through his head: age demographic, supernatural phenomena, Eros. Together, these incongruous terms coalesced into a phrase that felt positively surreal. Walker, a curator, didn’t see the absence of the object of his daughter’s desire; he saw a ready-made exhibition title.

And so “Teen Paranormal Romance” became a group exhibition of the same name. It was on view this past spring at the University of Chicago’s contemporary museum, The Renaissance Society, where Walker has been a curator for twenty years; and it recently opened at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. The theme of adolescence runs through the assembled artworks, but the exhibition is generous with meaning; like lodestones for memory, the artworks dislodge the bits and pieces of our adolescent desires and anxieties.

Anna K. E., Lucky Weekend, 2013, wood, tile, aluminum, clothes, paper, 236" x 96" x 65". Courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Kimberly Binns

Anna K. E., Lucky Weekend, 2013, wood, tile, aluminum, clothes, paper, 236" x 96" x 65". Courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Kimberly Binns

The largest sculptures in the exhibition have a grounding effect, evoking the ubiquitous settings of the American teenage experience. Anna K. E.’s Lucky Weekend is a stand-alone wooden wall covered in patterned white tiles; the wall’s framework is exposed on the other. The tiled side, which features layers of posters in addition to the patterned tile, is reminiscent of mass-transit public-art pieces: looking at it, one can imagine a pack of teenagers exiting the CTA or MTA en masse, traveling in packs through exit corridors, individuals made anonymous by virtue of the larger group. The other side, in its bareness, appears like the backdrop of a theater, a space tinged by the anticipation and thrill of imminent performance. A line of coats dangling from the exposed frame adds to the behind-the-scenes effect. There’s an implied virtue here, a kind of innocence.

The other works undo this naïveté. Kathryn Andrews’s Friends and Lovers—a large, physically domineering piece comprising an enclosed area of chain-link fence containing two concrete brick walls—teases at dualities. The fence has no opening or entrance, making it an exclusive space, a cage. A menacing feeling of school-yard hierarchies is heightened by the concrete walls, which create ominous hidden spaces. The inner face of each wall is painted with the head of a cartoonish black bear, somewhere between Grateful Dead and Berenstain. The bears leer at each other as if caught in a standoff—is their symmetry meant to critique a viewer who might look into a school yard (or prison yard, for that matter) and see sameness, generalizing the inhabitants within? Or does it imply the folly of spending too much time looking for answers in one’s own image?

Guyton\Walker, Canstripe_Mint_Mattress, Queenzebra_Desat_Mattress, Stripe_Turtle_22_Mattress, Canabstract_Pumpkinspice_Mattress, 2013, mattress, 80" x 60" x 8". Courtesy of the artists and Greene Naftali Gallery, New York. Photo: Kimberly Binns

Bare mattresses from a series by Guyton\Walker are strewn across the entrance to the exhibition—the remnants of yesterday’s sleepover. Sounds from Ed Atkins’s video Even Pricks blare throughout the space, adding to the abandoned-party effect. The video has the sparkle and dynamism of a Gillette commercial, but it picks at psychological anxieties. An upward thumb deflates like a balloon; the center of a bed turns ashen and collapses.

The smaller, wall-mounted sculptures in “Teen Paranormal Romance” appear like altarpieces to the burnout life. In the works of Jack Lavender, energy-drink bottles, dried limes, air fresheners, and other tchotchkes dangle from grid-like assemblages of steel bars. Two used pizza boxes studded with pushpins and grease hang in the gallery, as if their artist, Chris Bradley, is thumbing his nose at convention with dorm-room trash. But these pizza boxes have been painstakingly crafted out of cast bronze and aluminum, with trompe-l’oeil grease stains rendered in paint. Even the pushpins, which are situated like red eyes, are handmade.

Chris Bradley, Grease Face, 2011, aluminum, cast bronze, spray paint, adhesive hubcap ring, masonite, screw, color pencil, 24" x 22.5" x 3.25". Collection of Nancy and David Frej, Chicago.

Jack Lavender, Hannah, 2012, dried limes, magnum tonic wine bottle, posters, resin object, plastic peanuts, ocean scent air freshener, fire sealant, beer glass, Wimpy sugar packet, novelty magnets, sand in a bottle, plastic rock, energy-drink bottle, wicker object, steel, 51.25" x 31.5" x 9.5". Collection of Dr. Michael I. Jacobs. Photo: Kimberly Binns

Jill Frank, Bong (Shawn), 2014, c-print, 50" x 40". Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Kimberly Binns

In its second incarnation, “Teen Paranormal Romance” added a work by the photographer Jill Frank, whose image of a young man taking down a beer bong corresponds with the other photograph in this show: Roe Ethridge’s Louise with Red Bag. These pictures present the only recognizable human figures in the exhibition. Louise, blonde and fair, stands in a photography studio wearing a one-piece swimsuit featuring an image of a plane flanked by palm trees heading towards sunset. She affects a model’s insouciance, but her gaze betrays her discomfort. In Frank’s Bong (Shawn), our beer-swilling protagonist stands heroically, one arm raised as if in salute, the other presenting the nozzle of the beer bong to his face. This pose raises his shirt to reveal a vulnerable slice of pale navel. Louise and Shawn are presented as fragile archetypes of youth—the lovely girl hoping for supermodel stardom, the fratty coed engaged in a masculine display of endurance with presumably regretful consequences—but they also transcend the archetypes. Paired, they’re like face cards excised from a deck, Louise the self-conscious queen of hearts and Shawn the suicide king.

“Teen Paranormal Romance” conjures a desire to fabricate stories, to search for meaning with the plainness of an adolescent: in his or her own face, in a startling coincidence, in an unexpectedly lovely sight, in the smile of a stranger. This desire is hardly limited to youth, of course, but it begins in that uncertain time, when signs are misread as answers to questions you don’t even understand yet. No wonder we seek comfort in the paranormal; there’s something more knowable about creatures we’ve invented, even if they’re fantastical. But don’t look for vampires or werewolves here; you’ll still have to go to the bookstore for that.

“Teen Paranormal Romance” is on view at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center from October 25, 2014 through January 17, 2015. It will travel to the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara, where it will be on view from April 19 through July 5, 2015.

Lilly Lampe is a writer and art critic based in Atlanta, Georgia, and New York City. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, ArtAsiaPacific, Art Papers, Artforum.com, Modern Painters, and the Village Voice, among others. She currently teaches art history at Georgia State University.

The Poets Speak

Maya Angelou backstage at the 92Y.

At 92Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center, The Paris Review has copresented an occasional series of live conversations with writers—many of which have formed the foundations of interviews in the quarterly. Now, 92Y and The Paris Review are making recordings of these interviews available at 92Y’s Poetry Center Online and here at The Paris Review. You can consider them the deleted scenes to the printed interviews, or the director’s cuts, or the radio adaptations, or—let’s not dwell on it …

The latest editions to the collection are three poets: Maya Angelou, Denise Levertov, and Gary Snyder.

In this recording from 1988, Maya Angelou, who died this past May, speaks to our founding editor, George Plimpton:

I would be a liar, a hypocrite, or a fool—and I’m not any of those—to say that I don’t write for the reader. I do. But for the reader who hears, who really will work at it, going behind what I seem to say. So I write for myself and that reader who will pay the dues.

Denise Levertov died in 1997—Kenneth Rexroth called her “the most subtly skillful poet of her generation, the most profound, the most modest, the most moving.” Here she speaks to Deborah Digges in 1991:

Where I live in Seattle, I see a good deal more—more sky, more trees. I can see the lake. And from one upstairs window I can see a bit of Mount Rainier—when it’s out ... Who would want a mountain that was out all the time? You’d stop seeing it. It’s wonderful when it comes and goes.

And Gary Snyder, “the poet laureate of deep ecology,” talks to Eliot Weinberger circa 1992:

There’s no question that spending time with your own consciousness is instructive. You learn a lot. You can just watch what goes on in your own mind, and some of the beneficial effects are you get bored with some of your own tapes and quit playing them back to yourself.

We owe these recordings to a generous gift in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker, who worked in the art department at The Paris Review and volunteered as an archivist at 92Y’s Poetry Center.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers