The Paris Review's Blog, page 637

December 5, 2014

Staying Out of Trouble: An Interview with Julia Wertz

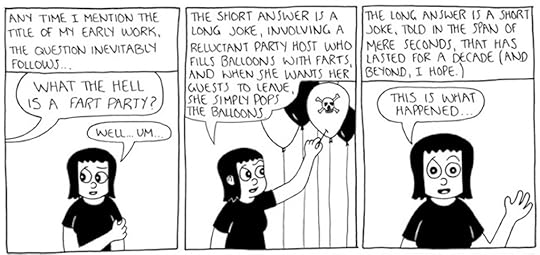

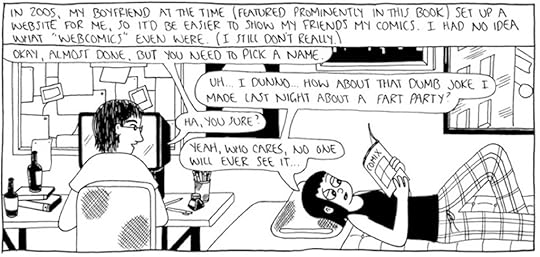

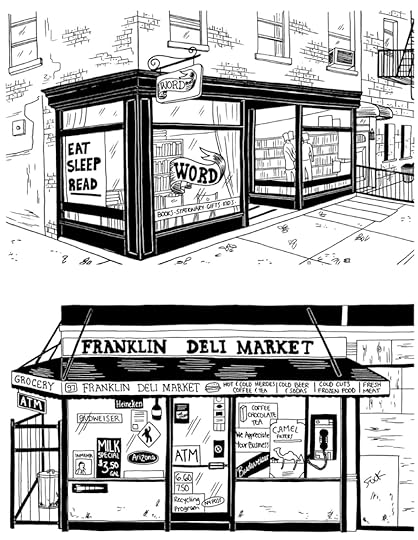

I met Julia Wertz at a slightly rundown family diner she’d recommended deep in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. We drank coffee and ate waffles (hers, covered in bacon) and whole-wheat pancakes (mine, covered in syrup). We’d talked briefly before, but always amid the clamor of comics conventions, where Wertz hustles hard to sell her books but does not relish being on display. Yet she has been putting her life online for nearly a decade. Her new omnibus collection, Museum of Mistakes, brings together three volumes of her autobiographical Web series called Fart Party, written between 2005 and 2010; miscellanea, such as hate mail and guest sketches; and a handful of previously unpublished stories, including one that delves into her past and how children process grief.

As the cartoonist Tom Hart has noted, Wertz “makes self-destruction charming.” In comics gloriously full of curses and insider jokes, she catalogs love found and lost, family dysfunction, and a risky cross-country move; she suffers low-wage service jobs and the publishing industry’s rush after indie comics darlings. Though Wertz’s frustration is often palpable (she occasionally imagines pulling people who annoy her limb from limb), she employs a kind of innocent visual style—her figures are wide-eyed and jaunty—and she’s adept at developing a sense of intimacy between the reader and her antisocial persona on the page. In other words, she lets you in, then flips you off.

Wertz has published two graphic memoirs since most of the comics in Museum of Mistakes first appeared: Drinking at the Movies (2010) and The Infinite Wait and Other Stories (2012). The latter is partly concerned with her diagnosis with Lupus and the horrors of navigating the health care system as an uninsured artist. She also recently chronicled her journey to sobriety in an essay for Narratively about comedy, depression, and addiction. A few years ago, she began documenting her urban-exploring exploits, posting haunting photographs of modern ruins on her site Adventure Bible School.

This fall, Wertz made a much-anticipated return to publishing new online comics that, as Gary Panter puts it, “look cute and nice, but they aren’t.”

You’re back to making daily diary comics after a two-year break. Why have you started again—and why did you stop?

I stopped because I was sick of myself. I completed the The Infinite Wait in only six months by drawing autobio comics sixteen hours a day. And before that, I had drawn comics every day, nonstop, for six years.

Eleanor Davis took a year after she finished How to Be Happy where she said, I’m only going to draw what I want to draw, when I want to—not what I need to for work, not what I think I should be working on. I used her example as justification, but I would have stopped anyway. I had planned to take a two-week break, and then, two years later, I was just ready to start again. I had remembered why I liked drawing comics.

What was it like rediscovering your older work? You’ve said, “I drank my way through my first three books, and consequently, I think they’re all garbage.”

Wow, I’m so harsh. I’ve been able to take enough time to appreciate these comics again. I realized that although I was an alcoholic when I made them, it doesn’t mean they aren’t good. Well, I don’t know if I would say good, but they’re funny. I also tried at one point to ditch the name Fart Party. I ended up reembracing it. Who fucking cares?

The early stories were drawn when alcohol worked for me. I write about it in a celebratory way, but if you look back knowing what happened to me later, you see that it’s excessive. I was also making an active choice during those years not to talk about the serious issues in my life, which were later covered in The Infinite Wait. My brother’s drug and alcohol addiction was slowly taking over my life, and I was sick. But in Fart Party, only every once in a while is there a panel that says, Oh, my brother fell off the wagon and got the shit kicked out of him but here I am, eating a cookie.

There is a striking scene in the saga in Fart Party of your now ex-boyfriend Oliver. You come in to bed at night drunk and he pushes you off him—he doesn’t find it sexy. With hindsight, it’s clear how your drinking was interrupting relationships.

It’s such a cute comic, and I thought that was funny when it first happened. Then it definitely happened more than just that one time. I put that poor guy through some ridiculous nonsense. You can’t conduct adult relationships like that, being out at four-thirty in the morning and not returning phone calls. Who does that? Alcoholics do that.

I love the comic your brother made, which is in Museum of Mistakes, about your obsession with Guns N’ Roses. It deals with a form of addiction, a subject you cycle back to throughout your work.

You see me going into a K-hole of Guns N’ Roses videos, not going to school, not wanting to participate in my own life. My brother swooped in, took the videos away, and then he started watching them. The pattern repeats itself later, when he had his addiction years and I swooped in to save him. That’s been a constant narrative in our relationship. The comic is a funny piece about me liking hair metal, but it also says more about me than my own work does.

What is your process? Do you keep a diary and draw from life?

I write out stories as they happen. I don’t have the luxury of retrospect. Retrospect is what most memoirs are written from—and that’s good, because you want to see people grow—but I prefer to create a narrative where I don’t afford myself the grace of afterthought. It’s embarrassing and raw. You have to watch me fuck up.

The Infinite Wait was the first story I wrote as a long-form script, but I pulled it from diary sketches. I did draw the stories of my childhood from memory, putting myself in the mind of a child rather than taking an adult perspective. I was selling golf balls, running off into the woods with my older brother and a dull pocketknife. We were on welfare when I was a kid, but I didn’t know it. I don’t attribute being poor to having a hard childhood. Rather, it forced my family to be together. If we went on vacation, we were all stuck together in my grandmother’s motor home, because at that time gas was maybe seventy cents a gallon. There were problems I was unaware of until later, when my parents broke up. But the good times are ingrained in my memory, and I like to write about them. It may make it painful because it all went bad later, but it’s that much more important to me to remember.

You’ve said that you originally tried writing short stories, but once you started telling stories with drawings, the art did the editing for you. How did that work?

Throughout my childhood and high school, I wanted to be a writer, but I don’t have the discipline to self-edit. I have good bones for storytelling, but I’m too loquacious and go off on too many tangents. I also wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t want to go to art class. I only wanted to draw what I wanted to draw. So I never was a good artist, and I never was a good writer. But with comics, I realized I could put art and writing together, and the physical constraint of nine panels or four panels creates an editorial process.

Within that framework, I look at a piece and ask myself what is absolutely essential—what can I draw, and what do I have to put in dialogue or words? Comics are minimal, so I can take three pages of writing and make a comic that’s nine panels. By selecting only the essential words and sentences, I see what I don’t need to talk about, where I don’t need to draw upon a tangent—I find all that matters.

You tend to

disparage your skills, but in The Museum of Mistakes you include juvenilia and process sketches, and I see how your drawing has evolved

. Is your style deliberate?

disparage your skills, but in The Museum of Mistakes you include juvenilia and process sketches, and I see how your drawing has evolved

. Is your style deliberate?

To paraphrase Charles Schultz, the simplest art form is the most effective. If you draw a simple face, readers can then project themselves into the story. In the early Peanuts, the characters were more childlike. The more “grown-up” versions are what most people know from the newspapers, but I prefer when they looked like kids. Similarly, in The Infinite Wait, I refined my drawings. But it’s like I decided to take it a little too seriously, for that book. In the comics I’m posting now, I am going back to my cruder, cartoony style from the Fart Party days. I’m going to play it looser.

I’m not a trained artist—that’s obvious. I can draw a good background, good buildings. It’s people I don’t like drawing.

That’s revealing!

I know, it’s my temperament in life.

The character Julia is so angry. I was a little afraid of you.

I’m a real bitch in my work. No one likes a happy-go-lucky character—that’s the character everyone wants to see destroyed. I portray and exaggerate the ugliest aspects of my personality. When I draw a comic where my eyes are bugging out, in real life I was mildly irritated at most. I build up an interaction in the story, and there’s an invisible end panel that I don’t draw, which is just me laughing at the situation. In real life, I’m more even-keeled, though I do my best work when I’m unhappy.

You regularly draw yourself in isolation. But cities—particularly New York and San Francisco—feature prominently in your stories. How do you relate to being an artist alone in the social architecture of a city?

I have a conflicted relationship with the city. I do live an isolated life—I live alone, I work alone, I travel alone. In my urban exploring I’m going to places where humans no longer are—that’s the objective. But even when I don’t want it, the city still provides human interaction. Even basic subway encounters force me to remember that I’m a human being, that we’re all here doing this together.

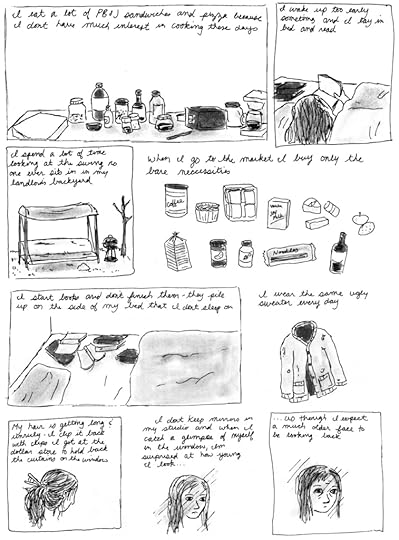

What’s “urban exploring”?

I explore abandoned buildings, take photos of them, and go treasure hunting. I research and write up the history of the places, then weave in some autobio.

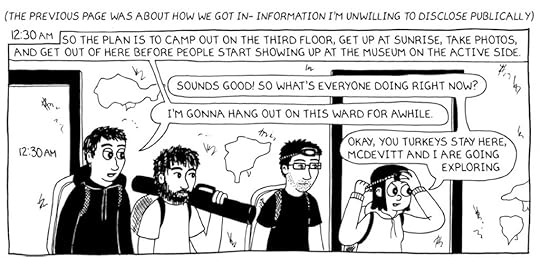

There are five levels of urban exploring. I don’t want to brag, but I’m very good at what I do. There are places, like Farm Colony on Staten Island, where you can walk right through a hole in the fence. Then there are decaying hotels and resorts, with cops on patrol, and, on a higher level, depending on security and the state of the building, an abandoned hospital and asylums. The fourth level includes super illegal sites to enter, like military bases and the subway system. Last, there are “world traveler” explorers—usually professionals, like photographers for National Geographic, who investigate places like Chernobyl and abandoned islands like Hashima in Japan.

Do you go alone?

I go alone if I’m familiar with the place. If I’m not, I bring a friend, because I don’t want to fall through the floor, and that’s how I die, laying there with two broken legs.

You publish photos and documents you find. You unearth people’s private lives. What is the legality of that and what are the ethical issues?

I’m holding onto a lot of paperwork, including patient files, from asylums. The institutions were supposed to destroy them when they abandoned the facilities. During the period of mass deinstitutionalization, from the sixties through the nineties, they considered files destroyed if they were sealed in the basement or the roof. But explorers get in there and discover people’s stories. We find diaries and interviews. In terms of legal issues, it’s trespassing and larceny. The ethical issues have to do with whether a patient has any living relatives. How much material can you publish and discuss without hurting family, without getting yourself in trouble?

I’m waiting to make some finds public. I’m waiting for buildings to be torn down. I’m also well versed in the statute of limitations for larceny and trespassing, so I’m waiting those out, too.

Are you searching for living family members?

I am hunting for the family of one patient who was institutionalized for homosexuality during World War II. He’s a genius. I found twenty years of handwritten personal letters where he’s writing to his mother, who is herself going into an institution. And she institutionalized him. The doctors talk about his IQ as a child, which was off the charts. In the documents, you see him go in an arrogant narcissist—he’s the worst, but I love him. He was totally functional, just gay. And he loses his mind completely over the years of being a smart person who’s institutionalized. Then he tries to go back out into the world, and he can’t function. He goes back to the hospital of his own accord. It’s so painful to see him unravel.

What compels you to share your own life?

It’s definitely not the money—there is none—and it’s not for fame or praise. I like doing it. I like talking about myself. It’s fun to ink. It’s fun to draw. It’s fun to tell stories. It’s a therapeutic process. When I cover something in a comic, it’s already a little less painful as I’m writing it. I can sit at home in my pajamas drawing and come to the same conclusions as I could by putting on pants, going to the city, and talking to a therapist. From a removed point of view, I look at myself on paper and identify behaviors that have to stop. I see patterns I can’t see otherwise. I’m learning about myself right along with the readers.

Meg Lemke is a contributing editor at MUTHA Magazine and chairs the comics and graphic novel programming committee at the Brooklyn Book Festival. You can find her online @meglemke and meglemke.tumblr.com.

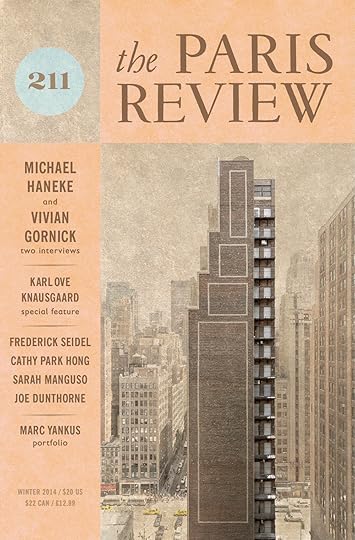

Behind Our Latest Cover

The cover of our new Winter issue features Stairs Building, a photograph by Marc Yankus, who’s been taking pictures of architecture since the nineties, though he doesn’t consider himself an architectural photographer. The building is in Manhattan, on Thirty-Ninth Street between Seventh and Eighth avenues. Marc wrote to me about it:

The cover of our new Winter issue features Stairs Building, a photograph by Marc Yankus, who’s been taking pictures of architecture since the nineties, though he doesn’t consider himself an architectural photographer. The building is in Manhattan, on Thirty-Ninth Street between Seventh and Eighth avenues. Marc wrote to me about it:

In Stairs Building, I was drawn to the strange design of the rectangles off the street-side facade and the discreet doors tucked away toward the back. I spotted the building from a rooftop party I’d attended—its unusual shape drew me in, and I felt compelled to come back and photograph it.

I’m not sure what it is about some buildings that just stops me in my tracks. Everything around them vanishes. I notice that I am often attracted to older architecture and unusual, forgotten buildings. For this portrait, I faded out the surroundings in a haze, making the featured building more prominent and monolithic.

This photograph was taken in mid-July, 2013.

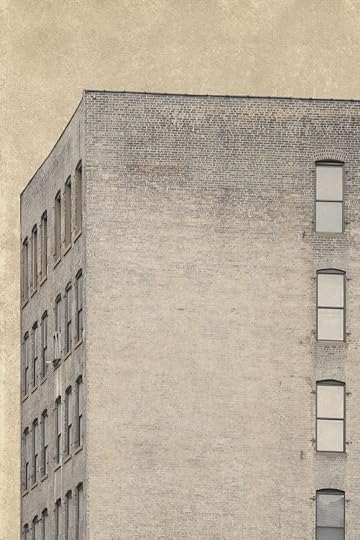

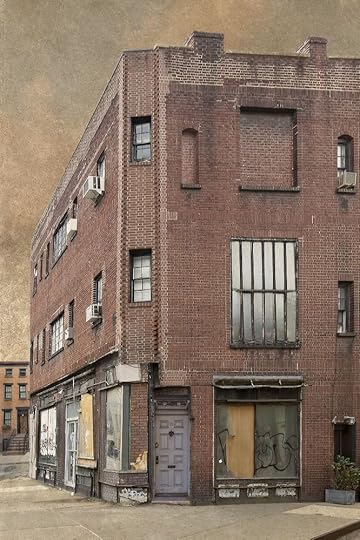

In our new issue you’ll find “The Secret Life of Buildings,” a portfolio of sixteen of Yankus’s pictures with an introduction from our art editor, Charlotte Strick. Subscribe now and have a look. In the meantime, here’s a larger version of Stairs Building, plus a few additional photographs not included in the portfolio:

Stairs Building, 2013, color photograph.

The Space Between, 2013, color photograph.

Yellow Ochre Building, 2013, color photograph.

Somewhere in the West Thirties, 2013, color photograph.

Inside Out, 2013, color photograph.

Holland Tunnel Tower, Across the Highway, 2014, color photograph.

Charles and Seventh, 2013, color photograph.

The Quick and Easy Way to Become a Pig, and Other News

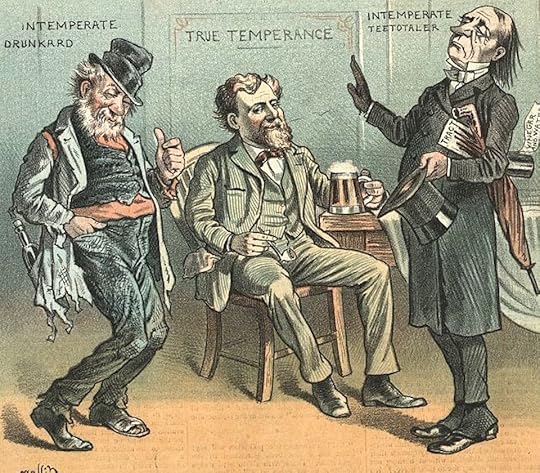

“Between Two Evils,” from Puck magazine, 1888.

“The kinds of books we’ve decided to ‘note’ have changed over time, and so have the books that loom largest in our imaginations or that we urge on our friends, even if similar books have been around all along. In other words, it may be the readers who have changed as much as (if not more than) the titles made available to us.” A history of the New York Times Notable Book list …

… and a history of humankind’s antipathy for drunkards—specifically their drunk, decaying bodies. “To [Edward] Bury, the most comparable creature to the drunkard was the swine, as drunkards seemed to take great pleasure in wallowing in their own vomit, dung, and the dirt. Drunkards even came to resemble swine by crawling about, after losing control over their ability to walk; though, while beasts are serviceable in this manner, Bury remarked, ‘the Drunkard [is] good for nothing but to spend and consume.’ ”

“There are Mayakovsky Streets in forty-five Russian cities and fourteen Ukrainian cities. There are three Mayakovsky Streets in St Petersburg, more than there are in the whole of Kazakhstan, which boasts only a couple, one in Almaty and one in Ust-Kamenogorsk. Triumph Square in Moscow was called Mayakovsky Square from 1935 to 1992; the metro station that serves it is still called Mayakovsky. Omsk seems particularly fond of the poet: as well as a street, it has a cinema and a nightclub (or rather a ‘youth relaxation complex,’ which I hope is a nightclub) blessed with the great man’s name.”

Want a way of predicting if a new word will become a fixture of the language or simply fade away? Use the FUDGE system (Frequency of use; Unobtrusiveness; Diversity of users and uses; Generation of other forms and meanings; Endurance of the concept).

Pantone’s color of the year is Marsala, “a reddish-brown shade that’s not quite as bright as Adobe clay but not as deep as brick … slightly more pink than your basic brown.”

December 4, 2014

The Lion Cage

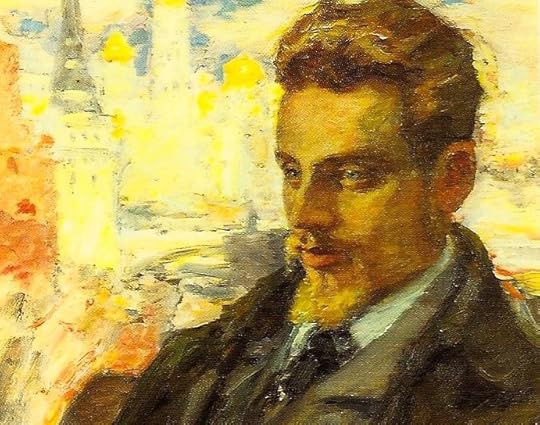

Detail from Leonid Pasternak, Rilke in Moscow, 1928

Rainer Maria Rilke was born on this day in 1875. The below is excerpted from “The Lion Cage,” one in a series of Rilke translations by Stephen Mitchell in our Summer 1989 issue.

She paces back and forth around him, the lion, who is sick. Being sick doesn’t concern him and doesn’t diminish him; it just hems him in. The way he lies, his soft bent paws intentionless, his proud face heaped with a worn-out mane, his eyes no longer loaded, how is erected upon himself as a monument to his own sadness, just as he once (always beyond himself) was the exaggeration of his strength.

[…] But he just lets things happen, because the end hasn’t yet come, and he no longer exerts any energy and no longer takes part. Only far off, as though held away from himself, he paints with the soft paintbrush of his tail, again and again, a small, semicircular gesture of indescribable disdain. And this takes place so significantly that the lioness stops and looks over: troubled, aroused, expectant.

But then she begins her pacing again, the desperate, ridiculous pacing of the sentinel, which falls back into the same tracks, again and again. She paces and paces, and sometimes her distracted mask appears, round and full, crossed out by the bars.

She moves the way clocks move. And on her face, as on a clock dial which someone shines a light onto at night, a strange, briefly shown hour stands: a terrifying hour, in which someone dies.

Stock

Photo: lyzadanger, via Flickr

There are a few things you need to understand about the particular grocery store I’m about to discuss. It’s part of a New York chain, but it is not what anyone would call a supermarket; it’s on the small side, for starters, with none of the slickness or charm one might associate with supermarkets.

It’s in a basement. You descend a broken escalator to a time that knows no season, no hour, no change. There is never any music playing; it is usually empty. There is a single, dejected cashier. It has that vaguely rancid smell endemic to urban supermarkets, with base notes of wet cardboard, old vegetables, and less-than-immaculate deli slicers.

Oh, and lest you think it is cheap—it’s not. The unit pricing is generally about 10 percent higher than that of the two other markets in a mile radius. Its one advantage is that it is open late, until midnight most evenings, although late-night trips there are even drearier than usual.

None of this is the point, however. The noteworthy thing about this market is its mysterious organization. Almost nothing is where you might expect it to be: baking needs share an aisle with cleaning supplies; pet food and dried fruit are cheek by jowl; spices are to be found in three different places, sorted by brand. (Herbs are in a different place completely.) The selection is vast, but arbitrary. On a recent visit, I found they had no whole milk—although they stocked no fewer than five varieties of eggnog, including dairy-free, low-carb, and organic.

The stockers, when they appear, are remarkable: you can ask where to find white vinegar and they’ll explain it’s next to a heretofore unknown Asian section in aisle three, as if it were the most natural thing in the world. And you will have to ask. Finding anything on your own is an exercise in frustration. If you do stumble upon what you need, it’s by sheer luck, and you don’t feel any sense of accomplishment.

Generally, I love wandering the aisles of a grocery store. Initially, I even thought it might be a fun challenge to myself to try to run to earth-tricky things. But after you learn that the liquid smoke is with the prebottled lemon juice and the candied peel is not with dried fruit, nor baking stuff, nor even candy, but is, in fact, in the produce aisle, this palls. The few other shoppers look disoriented and exhausted, and everything takes twice as long as you imagine it will. We’ve all read about stores that deliberately arrange their goods so that shoppers spend a long time on the premises—Anthropologie or Ikea. But this feels different.

The thought cannot help but intrude that the whole thing is an elaborate setup; that we are being gaslighted or maybe studied like mice in a maze. It would be an expensive experiment, yes, but as we know from movies, sinister higher-ups will stop at nothing in their pursuit of godlike omnipotence. Anyway, you start to feel that way after spending a few hours underground.

A Crazy Mixed-Up Day: Thirty Brainteasers

Image: Doyle Saylor

From 1927 to early 1933, Walter Benjamin wrote and delivered some eighty to ninety broadcasts over the new medium of German radio, working between Radio Berlin and Radio Frankfurt. These broadcasts, many of them produced under the auspices of programming for children, cover a fascinating array of topics: typologies and archaeologies of a rapidly changing Berlin; scenes from the shifting terrain of childhood and its construction; exemplary cases of trickery, swindle, and fraud that play on the uncertain lines between truth and falsehood; catastrophic events such as the eruption of Vesuvius and the flooding of the Mississippi River, and much more. Now the transcripts of many of these broadcasts are available for the first time in English—Lecia Rosenthal has gathered them in a new book, Radio Benjamin. Below is one of his broadcasts for children, including thirty brainteasers. We’ll post the answers next week.

Perhaps you know a long poem that begins like this:

Dark it is, the moon shines bright,

a car creeps by at the speed of light

and slowly rounds the round corner.

People standing sit inside,

immersed they are in silent chatter,

while a shot-dead hare

skates by on a sandbank there.

Everyone can see that this poem doesn’t add up. In the story you’ll hear today, quite a few things don’t add up either, but I doubt that everyone will notice. Or rather, each of you will find a few mistakes—and when you find one, you can make a dash on a piece of paper with your pencil. And here’s a hint: if you mark all the mistakes in the story, you’ll have a total of fifteen dashes. But if you find only five or six, that’s perfectly alright as well.

But that’s only one facet of the story you’ll hear today. Besides these fifteen mistakes, it also contains fifteen questions. And while the mistakes creep up on you, quiet as a mouse, so no one notices them, the questions, on the other hand, will be announced with a loud gong. Each correct answer to a question gives you two points, because many of the questions are more difficult to answer than the mistakes are to find. So, with a total of fifteen questions, if you know the answers to all of them, you’ll have thirty dashes. Added to the fifteen dashes for mistakes, that makes a total of forty-five possible dashes. None of you will get all forty-five, but that’s not necessary. Even ten points would be a respectable score.

You can mark your points yourselves. During the next Youth Hour, the radio will announce the mistakes along with the answers to the questions, so you can see whether your thoughts were on target, for above all, this story requires thinking. There are no questions and no mistakes that can’t be managed with a little reflection.

One last bit of advice: don’t focus on just the questions. To the contrary, keep a lookout for the mistakes above all; the questions will all be repeated at the end of the story. It goes without saying that the questions don’t contain any mistakes; there, everything is as it should be. Now pay attention. Here’s Heinz with his story.

*

What a day! It all started early this morning—I had hardly slept a wink, because I couldn’t stop thinking about a riddle—anyway, the doorbell rang early. I opened the door and there was my friend Anton’s deaf housekeeper. She handed me a letter from Anton.

What a day! It all started early this morning—I had hardly slept a wink, because I couldn’t stop thinking about a riddle—anyway, the doorbell rang early. I opened the door and there was my friend Anton’s deaf housekeeper. She handed me a letter from Anton.

“Dear Heinz,” writes Anton, “yesterday, while I was at your house, I left my hat hanging by the door. Please give it to my housekeeper. Best regards, Anton.” But the letter continues. Below he writes: “I just now found the hat. Forgive the disturbance. Many thanks for your trouble.”

That’s Anton for you, the absent-minded professor type. By the same token, he’s also a great fan and solver of riddles. And when I looked at the letter, it occurred to me: I could use Anton today. Perhaps he knows the solution to my riddle; I made a bet that I would figure out the riddle by this morning. The riddle goes like this (Gong):

The peasant sees it often, the king only seldom, and God never at all. What is it?

Yes, that’s it, I thought to myself, I have to ask Anton. I was hoping to ask his housekeeper whether he was already at school—Anton is a teacher—but she had already left.

I thought to myself, Anton must be at school. I put on my hat and just as I was heading down the stairs, it occurred to me that summer daylight saving time began today, so everything starts an hour earlier. I pulled out my watch and set it back one hour. When I reached the street, I realized that I had forgotten to shave. Just around the corner to the left I saw a barbershop. In three minutes I was there. In the window hung a large enamel sign: “A shave today ten pfennigs, a shave tomorrow free.” (Gong): A shave today ten pfennigs, a shave tomorrow free. The sign struck me as odd. I wish I knew why. I went in, took a seat and got a shave, all the while looking in the large mirror hanging before me. Suddenly the barber nicked me, on my right cheek. And sure enough, blood appeared on the right side of my mirror image. The shave cost me ten pfennigs. I paid with a twenty-mark note and got back nineteen marks in five-mark coins, along with five groschen and twenty five-pfennig coins. Then the barber, a jolly young man, held open the door and said to me as I went out: “Say hello to Richard if you see him.” Richard is his twin brother who has a pharmacy on the main square.

Now I’m thinking: the best thing is to go straight to Anton’s school and see if I can’t track him down. On my way there, walking down a street, I saw a large crowd of people standing around a carnival magician performing his tricks. With chalk he drew a tiny circle on the sidewalk. He then said: “Using the same center point, I will draw another circle whose circumference is five centimeters greater than the first.” After doing so he stood up, looked around with a mysterious smile and said (Gong): “If I now draw a gigantic circle, let’s say as big as the circumference of the Earth, and then I draw a second one whose circumference is five centimeters greater than that of the giant circle, which ring is wider: the one that lies between the tiny circle and the one five centimeters larger, or the ring between the giant circle and the one five centimeters larger?” Yes, I would like to know this, too.

I’d finally managed to push my way through the crowd, when I noticed that my cheek still hadn’t stopped bleeding, and as I was on the main square, I went into the pharmacy to buy a bandage. “Greetings from your twin brother, the barber,” I said to the pharmacist. He’s old as the hills and a bit of an odd bird to boot. And more than anything, he’s terribly anxious. Whenever he leaves his ground-floor shop, not only does he double-lock the door, he also walks around the whole building, and if he sees he’s left a window open somewhere, he reaches inside to close it. But the most interesting thing about him is his collection of curiosities, which he’ll show to anyone who comes into his shop. Today was no exception and, before long, I was left to admire everything at my leisure. There was a skull of an African Negro when he was six years old, and next to it a skull of the same man when he was sixty. The second was much larger, of course. Then there was a photograph of Frederick the Great, playing with his two greyhounds at Sanssouci. Next to it lay a bladeless antique knife that was missing its handle. He also had a stuffed flying fish. And hanging on the wall was a large pendulum clock. As I paid for my bandage, the pharmacist asked (Gong): “If the pendulum on my clock swings ten times to the right and ten times to the left, how often does it pass through the middle?” This, too, I wanted to know. So, that was the pharmacist.

Now I needed to hurry if I wanted to make it to the school before lessons were over. I jumped onto the next streetcar and just managed to get a corner seat. A fat man was seated to my right and on my left was a small woman talking to the man across from her about her uncle (Gong): “My uncle,” she said, “has just turned one hundred years old, but has only had twenty-five birthdays. How can that be?” This, too, I wanted to know, but we had already reached the school. I went through all the classrooms looking for Anton. The teachers were very annoyed at being disturbed.

And they asked the oddest questions. For example, I walked into a math class where the teacher was getting cross with a young boy. He had not been paying attention and the teacher was going to punish him. He said to the boy (Gong): “Add up all the numbers from one to a thousand.” The teacher was more than a little surprised when, after a minute, the boy stood up and gave the right answer: 501,000. How was he able to calculate so fast? This I also wanted to know. First I tried it with just the numbers one through ten. Once I came upon the quickest way to do this, I had figured out the boy’s trick.

Another class was geography. (Gong): The teacher drew a square on the blackboard. In the middle of this square he drew a smaller square. He then drew four lines, each connecting one corner of the small square with the nearest corner of the large square.This resulted in five shapes: one in the middle, this was the small square, and four other shapes surrounding the small square. Every boy had to draw this diagram in his notebook. The diagram represented five countries. Now the teacher wanted to know how many different colors were needed so that each country was a different color than the three, or four, countries that it bordered. I thought to myself, five countries need five colors. But I was wrong, the answer was smaller than five. Why? This, too, I wanted to know.

I then entered another class, where students were learning to spell. The teacher was asking very strange things, for example (Gong): “How do you spell dry grass with three letters?” And (Gong): “How can you write one hundred using only four nines?” And (Gong): “In your ABC’s, which is the middlemost letter?” To conclude the lesson he told the children a fairy tale (Gong):

“An evil sorcerer transformed three princesses into three flowers, perfectly identical and planted in a field. Once a month, one of them was allowed to return to her house for the night as a human. On one of these occasions, one of the princesses said to her husband just as dawn broke and she had to return to her two friends in the field and become a flower again: ‘If you come to me this morning and pluck me, I will be redeemed and can stay with you for evermore.’ This came to pass. Now the question is, how did her husband recognize her, since the flowers looked identical?” This, too, I wanted to know, but it was high time for me to get hold of Anton, and because he wasn’t at school, I headed to his home.

Benjamin in 1928.

Anton lived not far away, on the sixth floor of a building on Kramgasse. I climbed the stairs and rang the bell. His housekeeper, who had been at my house in the morning, answered right away and let me in. But she was alone in the apartment: “Herr Anton is not here,” she said. This irritated me. I thought the smartest thing to do was to wait for him, so I went into his room. He had a gorgeous view onto the street. The only hindrance was a two-story building across the way, which obstructed the view. But you could clearly see the faces of passersby, and on looking up, you could see birds fluttering about in the trees. Looming nearby was the large train station clock tower. The clock read exactly 14:00. I pulled out my pocket watch for comparison and sure enough, it was 4 pm on the nose. I had waited for three hours when, out of boredom, I started browsing the books in Anton’s room. (Gong) Unfortunately a bookworm had gotten into his library. Every day it ate through one volume. It was now on the first page of the first volume of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I thought to myself, how long will it need to reach the last page of the second volume of Grimm’s Fairy Tales? I wasn’t concerned about the covers, just the pages. Yes, this is something I wanted to know. I heard voices outside in the hallway.

The housekeeper was standing there with an errand boy, who had been sent by the tailor to collect money for a suit. (Gong) Because the errand boy knew the housekeeper was deaf, he had handed her a piece of paper with one word written on it in large capital letters: MONEY [GELD]. But the housekeeper had no money with her, so to convey her request that he be patient, she drew just two more letters on the piece of paper. What were these two letters?

I had had enough of waiting. I headed out to find a little something to eat after such a tedious day. As I reached the street the moon was already in the sky. There had been a new moon a few days prior, and by now it had waxed to a narrow crescent that looked like the beginning of a capital German “Z” hovering over the rooftops. In front of me was a small pastry shop. I went in and ordered an apple cake with whipped cream. (Gong): When the apple cake with whipped cream arrived, it didn’t appeal to me. I told the waiter I would prefer a Moor’s Head [i.e., a mallomar]. He brought me the Moor’s Head, which was delicious. I stood up to go. As I was just on my way out, the waiter ran after me, shouting: You didn’t pay for your Moor’s Head!—But I gave you the apple cake in exchange, I told him.—But you didn’t pay for that either, the waiter said.—Sure, but I didn’t eat it either! I retorted, and left. Was I right? This, too, I’d like to know.

As I arrived home, imagine my astonishment at seeing Anton, who had been waiting there for five hours. He wanted to apologize for the silly letter he had sent to me early this morning via his housekeeper. I said that it didn’t matter all that much, and then told Anton my whole day as I’ve just told it to you now. He couldn’t stop shaking his head. When my story was over he was so astounded that he was speechless. He then left, still shaking his head. As he disappeared around the corner, I suddenly realized: this time he really has forgotten his hat. And I—of course I had forgotten something as well: to ask him the answer to my riddle (Gong): The peasant sees it often, the king only seldom, and God never at all.

But perhaps you’ve found the answer by now. And with this, I say goodbye.

*

Repetition of the fifteen questions:

The first question is an old German folk riddle: The peasant sees it often, the king only seldom, and God never at all. What is it?

What’s fishy about a barber who hangs an enamel sign in his window reading, “A shave today ten pfennigs, a shave tomorrow free”?

If I have a small circle and then around its center point I draw a circle whose circumference is five centimeters greater than that of the original, this creates a ring between the two circles. If I then take a giant circle, one as big as the circumference of the Earth, and around the same center point I draw another one, whose circumference is five centimeters greater than that of the first giant one, there is then a ring between those two circles. Which of the two rings is wider, the first or the second?

If the clock pendulum swings ten times to the right and ten times to the left, how often does it pass through the middle?

How can a man who is a hundred years old have had only twenty-five birthdays?

What is the quickest way to add up all the numbers from one to 1,000? Try it first with the numbers from one to ten.

A country is surrounded by four other countries, each of which borders the middle country and two of the others. What is the fewest number of colors needed so that each country has a different color than its neighbors?

How do you spell dry grass with three letters?

How can you write 100 using only four nines?

In your ABC’s, which is the middlemost letter?

There are three identical flowers in a field. In the morning, how can you tell which of them has not been there overnight?

If each day a bookworm eats through one volume in a series of books, how long will it take for it to eat its way from the first page of one volume to the last page of the next, provided he eats in the same direction in which the series of books is arranged?

You have a piece of paper with the word money [Geld] written on it. Which two letters can you add to convey a request for patience [Geduld]?

What’s wrong with the logic of a man who orders a piece of cake, exchanges it for another once it arrives, and then won’t pay for the new piece because he claims he traded the old piece for it?

The old riddle once more, whose solution is worth four points because it has now appeared twice: The peasant sees it often, the king only seldom, and God never at all.

We’ll post the answers to these fifteen questions, as well as a list of the fifteen mistakes, next Thursday. Feel free to speculate in the comments section. Good luck!

Translated from German by Jonathan Lutes. Broadcast on Southwest German Radio, Frankfurt, probably on July 6, 1932. The Südwestdeutsche Rundfunk-Zeitung announced for the Youth Hour on July 6, 1932, at 3:15 pm, “‘Denksport’ [Mental Exercise], by Dr. Walter Benjamin (for children ten years and older).” “A Crazy Mixed-Up Day” was most likely the text Benjamin prepared for this broadcast.

This transcript appears in Radio Benjamin, available now. Reprinted with the permission of Verso Books.

Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) was a German Jewish Marxist literary critic, essayist, translator, and philosopher. He was at times associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory and is the author of Illuminations, The Arcades Project, and The Origin of German Tragic Drama.

Is There a Vespa?: An Interview with Michael Hofmann

Photo © Thomas Andenmatten

Michael Hofmann’s first collection of poems, Nights in the Iron Hotel, came in 1984, and in the ensuing thirty years he has translated more than sixty novels from the German and published five more poetry collections, along the way collecting numerous prizes for his work. He is the editor of an anthology, Twentieth-Century German Poetry, and in 2002 published an earlier collection of critical essays, Behind the Lines. (This is far from a comprehensive accounting.) The thirty essays in his new collection, Where Have You Been?, visit a range of poets, novelists, and artists of the last hundred years, including Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, Thomas Bernhard, Kurt Schwitters, and Frederick Seidel.

Hofmann’s essays are intense inquiries: he tunnels deeply, engages profoundly, and whether or not he likes what he’s read or seen, his essays ennoble the work under review. There’s a sense of humor, even joy, electrifying the enterprise. Of course, his criticism can pulverize, too—Günter Grass and Stefan Zweig are destroyed in Where Have You Been?—but most of Hofmann’s selections tend toward the form of one reader grabbing another’s sleeve and shouting, Come on now, this way! You’ve got to see this!

Though Hofmann doesn’t keep a computer at home—“usual Luddite setup,” he said at one point—this interview was conducted over e-mail. On a couple of occasions, he wrote from a stand-up terminal in a municipal library.

You’ve written that contemporary American poetry is “a civil war, a banal derby between two awful teams.” In Britain, it’s “a variety show.” These are grim assessments.

Discouraging, isn’t it? It’s just a fact that there are never very many poets around at any given time. I think poetry is always one or two poets away from extinction anyway. If it’s any comfort, it’s not a living tradition—it doesn’t depend on being passed from hand to hand. It could easily go underground for a couple of decades, or a couple of centuries, and then return. People disappear, or never really existed at all, and then come back—Propertius, Hölderlin, Dickinson, Büchner, Smart. Poetry is much more about remaking or realigning the past than it is about charting the contemporary scene. It’s a long game.

Also, it’s not about extent, never about extent, not about numbers or range or choice. It’s not a supermarket. You can’t roam around, and read x on one day, and a the second, and b the third, not if you have taste and take it with you everywhere. It’s a condition of poetry that you can’t read everyone. What is it Lowell’s Harriet says— “You can’t love everyone—your heart won’t let you.”

It’s about depth, and what you find in it. The question isn’t, Who would I like to read now for the first time? It’s, I have these six poets. I must have read them all a hundred times. They’re just about all I read—it’s years since I read anyone else. Which of them do I feel like reading for the hundred-and-first?

Whose books do you wait for? That’s the question. Precious few. I’m not a generalist or a charity. Who interests me? Seidel, Paulin, Solie.

Precious few.

I think there’s always been an element of absence for me, of what’s not there. The first thing I heard about Lowell, at a time when I was still mispronouncing his name, was that he had just died. In England, the great poets from the seventies and eighties were literally over the water—they were the Northern Irish pleiade of Heaney, Longley, Mahon, Paulin, Muldoon. I read German poets, but without being in Germany when I did. Who was the greatest poet in America in the seventies and eighties? Joseph Brodsky. The spark has to fly, or is the better for flying.

And then there’s what one imports into poetry—from novels, from biographies, from films, from paintings, from other, acute cultural references. For a long time, I don’t think I made up a single title of my own. They were all “borrowed.” Poetry grows on all kinds of rubbish, as Akhmatova says. Whereas the kind of hydroponic poetry that sustains itself was always an object of horror and incredulity to me. A library with nothing but the poetry of the past two years—and I’ve seen them, people have them—would send me round the twist.

In an essay on Kurt Schwitters, you write that “badly heard or badly reproduced music is more moving than expensive acoustic perfection can ever be.” Is there a way to approach your philosophy of translation through that fragment?

I’m thinking of a mixture of Laforgue poems—some of the “Dimanches,” maybe?—and certain scenes in Joseph Roth, hurdy-gurdies, street musicians, public music, marching bands. Rimbaud’s “A la musique.” Rilke near the beginning of the First Elegy, the violin through the open window. But it’s true. You hear a snatch of something from a passing car, and you worry at it until you’re able to place it, or not. Those few second instrumental shifts on NPR—I’ve heard this before somewhere, what is it? And then it’s things like the Keep it with Mono side of Stiff Records. Lo-fi. People go to concert halls to show off their coughs. The unpampered ear does more. Once when I was in Michigan for a term, and didn’t have a record player, someone in Shaman Drum put on Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, and I had to stay there browsing unobtrusively for the next forty minutes, feeling like a pervert. That’s music starved, that’s not bad repro. I suppose the Brit in me believes in a degree of adversity. The less than ideal. Bad weather. The ideal is often only sterile.

As for the connection to translating, I can’t offer you consistency there—or necessarily anywhere else for that matter. I think Brodsky would have gone for that, and maybe Nabokov as well. Something not slick, something that betrays its noble difficulties, something that has an accent, so to speak. It’s the loyalty of exile, to the past, the other, the original … It’s a pleasing idea, a lovely idea, but you wouldn’t want to be the party responsible for the awkward rendition. Or I wouldn’t, anyway. I have a different imperative. The need to “pass.” The desire to make something near autonomous, deceiving, and of high quality—in English. The translation as immigrant.

Do you think a faithful translation can be more moving than the original?

Do you think a faithful translation can be more moving than the original?

Yes, I do. It would be like something sung by a different voice or played by a different instrument. But it’d be perfectly possible for slovenly up-and-down English to offer a better home to some foreign text than the foreign language in question. And variations of the above. We had a lovely intellectual schoolmaster who told us he thought Proust was better in the Scott Moncrieff—and that not from ignorance or monolingualism. Scandalous!

You don’t own a TV and “don’t really approve of seeing films except in cinemas.” Writing about The Passenger, you describe a specific shot but note that you might have inserted a Vespa where there wasn’t one. It would have been easy enough to pull up the scene and confirm your hunch, but you chose not to.

I think that’s—paradoxically—a question of manners or acculturation. Too positive or definitive a reference, something too categorical, would just sound bossy to my fey British ear … It feels courteous to leave some room for error or inaccuracy—which I’m going to need anyway! It’s difficult—I’m too old to rely on my memory, and far too old to have adapted to Google’s exomemory facility. I like the chiaroscuro of a little measure of uncertainty. Is there a Vespa? I think there might be. It would be good if there were one. Maybe not.

You’re condemned to permanent rereading anyway. You can do mathematics on a blank sheet of paper. For literature—criticism—you need a full one. (Unless you’re Auerbach, who had memorized the texts he wrote about.) I have a memory that reduces a poem to three or four discrete lines or half lines. Greatest Hits, and nothing over ten seconds. Maybe that’s why I like Lowell so—he looks particularly good like that. Some people’s memories are like abundantly furnished rooms. Mine is liked a half-wrecked carpenter’s shop.

As you worked on the arrangement of these essays, did they communicate with each other in ways you hadn’t expected?

Yes, in a kind of call-and-echo. It may appear to be negatively conditioned—a narrowness of reference—and I’d have to accept that, except that there’s also a perfectly reckless and deliberate cross-referring. Take the end of the last piece, on Robert Walser. There’s a reference to a line from another one of my subjects, John Berryman—“The Bach-Gesellschaft girdles the world.” Now, I could quite easily have left that out, and it would probably have had the effect of making me seem even more learned, but I wanted to leave it in. The book doesn’t have an index, but I’d be surprised if there are many people or works that appear in it just once. So the effect is something like that of a carousel or a big wheel. “Und dann und wann ein weisser Elefant!” the Rilke line. It’s an Ark or a biotope. “Meet my critters.”

This is a complicated, essential, idea—“I translate to try to amount to something … To repair a deficit of literature in my life.” What do you mean?

That goes back to a feeling of inadequacy I’ve had really forever, since I got my first copy of my first book of poems in my hands, and it felt like an airmail letter. If I flipped it up in the air, I thought it might never come back to me. My father was a novelist, so it’s bred into my fingers to expect a little more heft from a book, something a little thicker in the way of a spine. If Kafka hadn’t said it, then I would say it—“literature, from which, or out of which I am composed.” Perhaps I’ll say it anyway, echoing Kafka. When my father’s first book appeared, I was twenty-one or so. I called it his firstborn, in a poem written not long after. We defer to print, where I’m from. Quite soon, I’ll be like that Arcimboldo painting, all book.

Jack Livings is the author of a collection of stories, The Dog, published earlier this year. The title story originally appeared in The Paris Review, where he has also published interviews with Tobias Wolff and Salman Rushdie.

“We Want You to Eat More Pies,” and Other News

The Orwell in Wigan, a town in Lancashire.

In the sixty-five years since Orwell’s death, his reputation has only grown, spawning a cottage industry for Orwell tourism. “The strangest place associated with Orwell is Wigan, the town in Lancashire where he stayed in February 1936 … one of the warehouses by the canal, opposite National Tyres and Autocare, has been converted into The Orwell, which offers weddings and civil ceremonies from £900. The local specialty is meat pies. Outside the pub a poster shows Uncle Sam holding out a pie, with the slightly Big Brotherish message: ‘We want you to eat more pies.’ ”

“Adrift on warm currents, no longer of this world, she became aware of him gliding into her … The universe was in her and with each movement it unfolded to her. Somewhere in the night a stray rocket went off.” The long-awaited winner of this year’s Bad Sex in Fiction Award.

A bunch of prominent scholars are bickering about the possibility that Shakespeare was gay. “Such figments of the critic’s imagination not only produce quantities of waste paper but … are inimical to the proper reading of poetry,” one wrote.

And while we’re being litigious: the Maurice Sendak estate is embroiled in a debate about his will, which stipulates that his house in Ridgefield, Connecticut—where, two years after his death, his slippers still sit next to his bed—become a study center and museum. “I really don’t know who’s going to go there,” his longtime British editor said. “It’s in the middle of nowhere.”

A new book of photographs “reveals the British West Indian experience of death in all its pathos, occasional comedy, and life-affirming sense of the funeral as essentially a fun-for-all … In [Charlie] Phillips’s moving and often beautiful images, dating from 1962 to the present, the bereaved are seen to face the mystery of the end of life in stush black suits, spidery hat veils, Rastafari head-ties, spiffy trilbies and strictly-come-dancehall white socks.”

December 3, 2014

Douglas Coupland Is Covered in Gum

Photo via Escape Kit

Douglas Coupland—you know him. Author of Generation X, and conflicted progenitor of the same term; occasional Financial Times columnist; one-time Paris Review Daily interviewee.

You may now see his likeness swathed in chewing gum.

Coupland, who’s also a visual artist, constructed a seven-foot sculpture of his head from polyester and resin. It sat outside the Vancouver Art Gallery all summer long, where passersby were encouraged to deposit their gum on it.

He calls it … Gumhead.

“At first the added gum looked like jewels against the black,” Coupland said in an interview. “I’ve never seen people interact so intimately and for such a long time as they do with Gumhead. And people who drive past it every day like to monitor its progress. It’s eight pieces in one: a self-portrait, a still life, a landscape, social sculpture, performance art, conceptual art and time-based art. And it wants to be your friend.”

You may be jealous of the citizens of Vancouver—I am, kind of. For who doesn’t harbor within oneself the latent desire to cover one of the nineties’ most prominent literary names in bits of flavored, food-grade butyl rubber, wet with one’s own saliva? You can do that in January, in Toronto, when Gumhead—restored to its original pristine condition—arrives as part of Coupland‘s “everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything” exhibition.

Pro tip: bring colorful gum. “The big surprise,” Coupland said, “was mango-flavored Hubba Bubba, which provides rich vibrant deep yellow hits of color. Also, people don’t seem to chew pink bubble-gum much any more. It’s like almost the entire gum industry has moved over to off-whites. This is a loss for society.”

Photo via Escape Kit

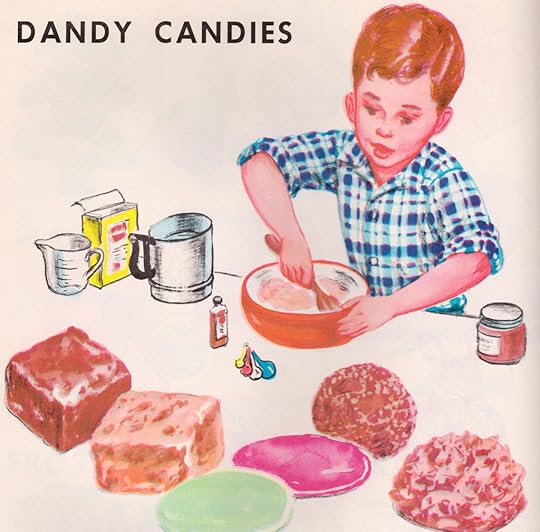

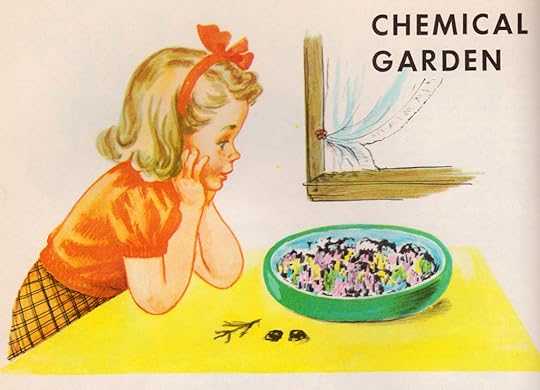

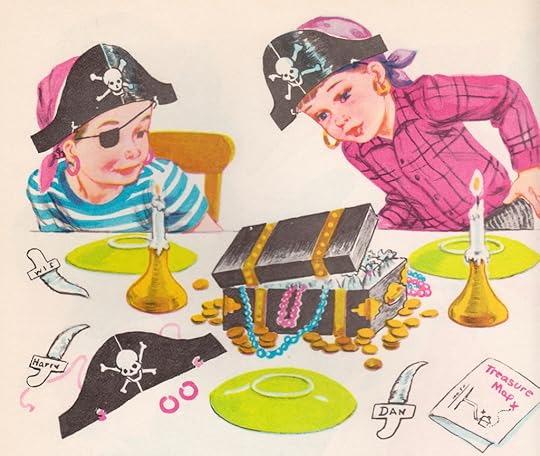

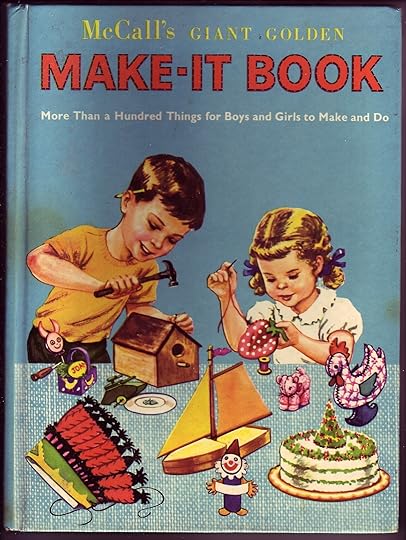

Make It

“More Than a Hundred Things for Boys and Girls to Make and Do.”

Here’s a gift idea for you, suitable for children and arrested adults—which is to say, a large part of your Christmas list. Go online at once and buy several copies of McCall’s Giant Golden Make-it Book.

Until recently, I had totally forgotten about the Giant Golden Make-it Book, but I ran across a copy at a used bookstore and immediately realized how well it’s held up. Simply put, no modern activity book can compare. It’s truly giant, and really comprehensive, but like the same-vintage Betty Crocker’s Cookbook for Boys and Girls, it’s as much about the illustrations as the ideas. A smart publisher has seen fit to reissue the latter; McCall’s really needs to do likewise.

There’s everything you might hope for—games and homemade costumes and simple recipes and easy knitting instruction and theme parties—but also a lot of things that never occurred to you. Dutch painting! Soap carving! Elementary flower arranging!

Because this giant golden book was popular, and came out in several editions in the fifties and early sixties, it is not that hard to find. It was also well made, so despite its age and the fact that it was intended for young children, a lot of the sturdy volumes—hardcover, issued without a dust jacket—have held up.

It is of its times, and some things date. A modern equivalent would certainly illustrate a wider range of children, for starters. But it’s not particularly gendered—boys and girls do all the activities interchangeably.

One of the difficulties for the modern child user would be sourcing some of the materials: say, acquiring the copper sulfates for your chemical garden.

What I like about this book, as both a child and now as an adult, is the sense of possibility it gives children. Not only does it suggest almost total self-sufficiency, but between the covers is hundreds of hours of proof that one need never, ever be bored.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers