The Paris Review's Blog, page 635

December 11, 2014

Time Bandits

The New York Historical Society’s underwhelming time capsule. Photo: New York Historical Society

If you enter the New York Historical Society by its Seventy-Seventh Street side entrance, you’ll see before you a smallish chest: a time capsule, the plaque explains, created in 1914 by the Lower Wall Street Business Men’s Association. It was supposed to have been opened in 1974, but everyone forgot about it, so the powers that be decided to wait until this year, the 400th anniversary of the New Netherland charter. In October, they opened it, and the results proved so generally underwhelming and dry—some newspapers, some charters, a few catalogs—that the New York Historical Society was inspired to make a better one.

To ensure that Capsule 2114 would be more hep and happenin’, the society asked high school students to contribute items. These include smartphones, e-readers, a Lady Gaga concert ticket, and a T-shirt that reads, SOME DUDES MARRY DUDES, GET OVER IT.

The problem with any contemporary time capsule is that so much of what’s truly reflective of our culture is ephemeral, and in the literal sense. For instance, any real memorial to the second decade of this century would need to include Someecards. Described by Wired as “the Hallmark of the web,” this wildly popular company combines old-time stock images with cheeky, deadpan captions to create commentary for basically any event in modern life. Belated birthday? Cynical Valentine? Pregnancy scare? Someecards has had you covered for the past five years. As the founder told Wired, “We like to play off the minutiae of life and call attention to it in a funny way. When you’re being honest, stuff comes out that people usually don’t talk about because it’s dark, dirty, or inappropriate.”

We’ve all gotten them, and many of us have used them. Recently, I created my first: a seventies-looking couple juxtaposed with the caption “I mean, Christ (is born).” I categorized it under “Christmas.” So far it has failed to become one of the site’s most popular offerings.

When a friend successfully defended his dissertation last week, I hied to the “Congratulations” section of the site to send him some free, pre-fab acknowledgment of his accomplishment. Someecards did not disappoint. Or, at any rate, they had plenty of topical options. “My Thesis is ruining my life,” says a card featuring a pensive-looking Victorian maiden at a desk. Another portrays a smiling 1980s woman at a desktop: “I worked on my dissertation today by pinning motivating pins on Pinterest about working on my dissertation,” it reads. Or there’s the etched judge at the bench: “Congratulations on plagiarizing Wikipedia enough times to get a degree.”

And that’s just for starters. Maybe you want to send something more general: “You’re not as complex as you think.” “I’d blow a pharmacist for 2 mg of Klonopin.” “The iPhone 6 will have a larger screen for me to repeatedly shatter.” “The last time I saw you I was hoping it was the last time I saw you.” “I would rather be sitting on a toilet with no toilet paper than no cell phone.” “Someone asked me if I wanted to have another child and right before I could answer my uterus jumped out of my body, into oncoming traffic.”

Recently, an article in the Wall Street Journal touted the therapeutic effects of cooking and baking; the sense of accomplishment and absorption in tasks is helpful for those dealing with depression and anxiety. Now, I’m not a therapist—I’m not even a psychiatrist!—but it seems like if reward neurotransmitters are helpful to troubled folks, looking at hundreds of Someecards in a row is the opposite. You’d need to run a controlled study to really prove it, but from anecdotal evidence I can tell you that what might seem innocuous or even mildly amusing in a vacuum becomes mind numbing, depressing, disheartening in large doses. It is like living in a vat of curdled milk. It is bad for the mind and, I would argue, worse for the soul.

And yet, this should be in the time capsule. If the point is to capture the Zeitgeist, how better to do so? I have even made a card for the purpose. The denizens of 2114 can thank me later.

Our Holiday Pop-up Shop Is Coming This Sunday

We’re making a banner and everything. That’s how serious we are.

Experts (i.e., us) have found that holiday shopping is altogether more bearable when there’s food and drink involved. Which is why we’re opening a pop-up shop in a restaurant.

If you’re shopping downtown this Sunday, December 14, come visit us at Contrada, a cozy Italian restaurant in the East Village at 84 East Fourth Street. From three-thirty to six-thirty, we’ll be there with discounted subscriptions, back issues, T-shirts, and boundless reserves of holiday cheer (i.e., snacks and drinks). We’ll gift wrap anything you’d like to give as a present. Stop by and say hello!

If you’re not in New York, you can still get a gift subscription to The Paris Review—just forty dollars for a year’s supply of fiction, poetry, interviews, and art, including a postcard announcing your gift with a personal message. They make a great present for aspiring writers, who should, in the words of William Kennedy, “read the entire canon of literature that precedes them, back to the Greeks, up to the current issue of The Paris Review.”

Order before December 15 and your gift is guaranteed to arrive by Christmas.

Erasing Duchamp

On Marcel Duchamp, Mad Libs, and conceptual writing online.

Five-Way Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1917.

As Marcel Duchamp had it, an artist is nothing without an audience. No work of art—no balloon dog, no poem mentioning cold-water flats, no four-minute-and-thirty-three-second performance by silent musicians—is a great work until posterity says so. In a 1964 interview between The New Yorker’s Calvin Tomkins and Duchamp, the latter remarked, “The artist produces nothing until the onlooker has said, ‘You have produced something marvelous.’ The onlooker has the last word in it.”

This is also a tidy summary of Duchamp’s short lecture “The Creative Act,” given in Houston in 1957, in which he calls the artist a “mediumistic being,” one whose “decisions in the artistic execution of the work … cannot be translated into a self-analysis.” Analysis is the work of the spectator, who “brings the work in contact with the external world.” Posterity decides if an artist’s works are deserving enough of an extended solo show at the Whitney, or should be reprinted in every iteration of the Norton Anthology until the end of time. The “creative act” is a transaction between artist and onlooker, and in it, again, the onlooker has the last word.

This is literally true in Joe Milutis’s new conceptual project Marcel Duchamp’s The [Creative] Act, released last month via Gauss PDF. Milutis’s text is a free fourteen-page PDF file that takes Duchamp’s 1957 lecture and turns it into a sort-of Dadaist Mad Libs:

Millions of artists [verb]; only a few thousands are [passive verb] or [passive verb] by the [noun] and many less again are [passive verb] by [noun].

In the last analysis, the [noun] may shout from all the rooftops that he is a [noun]: he will have to wait for the [noun] of the spectator in order that his [noun] take a [adjective] value and that, finally, [noun] includes him in the primers of Artist History.

Between each page of text are images of the error messages and broken links familiar to anyone who’s ever used the Internet: “We’re sorry, this image is temporarily unavailable”; “No Image Available”; “Sorry No Pic.” Of course, nothing is “temporarily unavailable” here. There were never any images in the first place.

From Joe Milutis’s Marcel Duchamp’s The [Creative] Act.

It’s not a typical erasure, if such a thing exists; it isn’t like Matthea Harvey’s Of Lamb, for example, a book-length poem derived from erased passages of a Charles Lamb biography. It seems more what we might call pop-Derridean conceptual writing. In the blank spaces he’s made, Milutis could have simply written “[redacted]”—instead, he supplies labels as guideposts of a sort, announcing exactly what kind of absence he’s presenting. And it’s crucial to remember the context here: this is a speech about how we lend meaning to a work of art. By excising certain words like this, Milutis forces us to do the very thing that Duchamp has asked of us.

But we shouldn’t take this to be all so cerebral. Milutis’s gesture is by and large a playful one. For instance: Where Duchamp repeatedly uses the expression à l’état brut (“raw state”) to refer to art before it is deemed good or bad by an audience, Milutis redacts the French, replacing it with “[french phrase].” We might decide à l’état brut should be avoir le cafard (have the cockroach) or si ma tata tâte ta tata, ta tata sera tâtée (if my aunt feels your aunt, your aunt will be felt).

This is the kind of niche project that the digital publisher Gauss PDF is becoming known for among a small set of literary netizens. The site itself looks deceptively minimal—it’s built using a simple Tumblr template, displaying almost no information about the authors or the works published. It would be easy to land on it from another page, think, What?, and move on.

And your What? wouldn’t be misplaced. Available for download right now on the site’s front page is a JPEG file that, when opened, displays the words BÊTE NOIRE dozens of times in various sizes and colors. There’s also The Comedy of Hamlet, in which the consonants in each line have been replaced with the letter h, so that every character’s utterance is reduced to giggles. Gauss PDF’s founder, J. Gordon Faylor, has established what is, in some ways, an initiative with a Dadaist spirit. A PDF published earlier this year, Adam Braffman’s “Bestseller,” compiles hundreds of one-sentence summaries of books that have appeared on the New York Times best-seller list over several decades. The names of the books themselves are never given; the summaries are simply strung together as a disorienting narrative. (“Men seek the green turtle with the sea around them. The exploits of a woman and her two daughters from pre-World War I Paris to present-day Los Angeles. King David tells his story in comic and irreverent style.”) And Dandyisms, a short poetry collection by the conceptual writer and poet Felix Bernstein under the name of his Victorian camp character, Leopold Brandt.

The most effective conceptual writing, as with all conceptual art, alters a thing’s accepted context. Critics would have you think that all this is merely silly, but in the best cases there’s a method to the madness: these artists are doing the very basic, very necessary work of helping us see with new eyes. When Kenneth Goldsmith transcribed, word for word, baseball sportscasters narrating the longest ever nine-inning game (Yankees vs. Red Sox, 2006), and then published the transcript with no edits—even the commentators’ stuttering is preserved—as a book called Sports, readers didn’t open it hoping for a riveting depiction of that game. Likewise, in 1917, when Duchamp took a urinal, signed it R. Mutt, and then submitted it to be presented in a show by the American Society of Independent Artists as Fountain, the committee of curators didn’t approach it looking to pee. Of course, we can glean a lot about sports coverage from Sports—and about circumlocution and observation and the human need to keep things interesting. And anyone is certainly able to pee on reproductions of Duchamp’s urinal—many have tried. But we understand these works as having new meanings beyond their original context.

Milutis has complicated Duchamp’s famous ready-made, which has, of course, seen no end of complications since its debut. “Marcel Duchamp’s The [Creative] Act” isn’t already-made. It’s still in the process of being made. However tongue-in-cheek this Mad Libs approach is, though—and however many eye rolls it, along with the rest of the Gauss PDF list, might garner—it’s a transaction I think Duchamp might enjoy.

Rebecca Bates has written for Guernica, Nylon, The New Inquiry, and elsewhere. Her poems have appeared in the Believer, Gigantic, Gulf Coast, Best American Experimental Writing, and other places.

The World Just Wasn’t Ready, and Other News

Rest in peace, WebVan. Photo: Mark Coggins, via Flickr

Tim Parks was dismayed to find that his students were so enthralled by “the printed word and an aura of literariness” that they’d miss obvious absurdities in what they were reading. His advice? “Always read with a pen in your hands, not beside you on the table, but actually in your hand, ready, armed. And always make three or four comments on every page, at least one critical, even aggressive. Put a question mark by everything you find suspect. Underline anything you really appreciate. Feel free to write ‘splendid,’ but also, ‘I don’t believe a word of it.’ And even ‘bullshit.’ ”

On a similar note, Oxonians are obsessed with finding marginalia in their library books: on Facebook, the Oxford University Marginalia group “now has two thousand five hundred and three members, making marginalia to Oxford something like what a cappella is to Princeton. ‘The Oxford libraries are still heavily used, and the curriculum remains relatively stable, so you have so many students reading the same texts’ … ‘The books are thrashed, basically.’ ”

Not many people are managing to slog through literary best sellers, experts say: “A study has shown the most downloaded ebooks of the year were not necessarily ever finished by hopeful readers.” Just 44 percent of readers made it through The Goldfinch, and 28 percent got through Twelve Years a Slave.

Crummy computer news, part one: they’re better at flirting than we are. “Women were okay, able to judge with 62 percent accuracy when a man was flirting with them. Men were worse, accurately guessing that a woman was flirting just 56 percent of the time. The Stanford guys’ flirtation-detection system, in comparison, was able to correctly judge flirting with 71 percent accuracy.”

Crummy computer news, part two: all the seemingly horrendous dot-com ideas of the nineties were actually pretty decent. Remember WebVan? No? They wanted to use the Internet to deliver fresh groceries to your door—just as dozens of profitable companies are doing today.

December 10, 2014

It Changes Nothing

If you’ve never seen it, watch Clarice Lispector’s first and only TV interview, from February 1977, when she appeared on TV Cultura in São Paulo. She’d arrived intending to appear in a program about film, apparently, when the station’s director summoned his nerve and asked for an interview. She died later that year.

Lispector is restless, and charmingly curt, throughout the interview—it seems as if she really, really doesn’t want to be there. Even under duress, though, she gives stronger, more meaningful answers than many writers give at their most accessible. “I write without the hope that what I write can change anything at all. It changes nothing … Because at the end of the day we’re not trying to change things. We’re trying to open up somehow.”

At one point, the interlocutor asks, “What, in your opinion, is the role of the Brazilian writer today?”

“To speak as little as possible,” she says, her head tilted, her thumb half-massaging her temple, a cigarette between her fingers.

Letters from the Earth

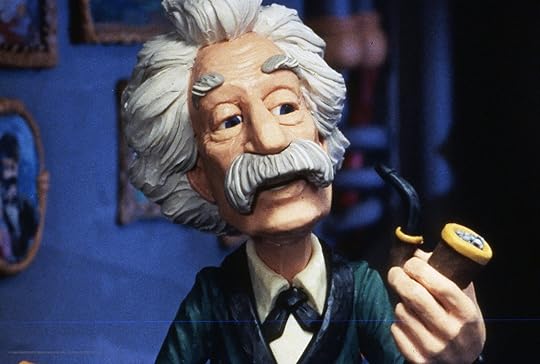

A still from The Adventures of Mark Twain, 1985.

The Internet is filled with half truths, dead ends, and flat-out lies. But to my mind the single greatest disappointment is on YouTube: the video called “Mark Twain’s Voice.” I’ll admit, it’s interesting in its own right. (And it does lead one to Val Kilmer’s Mark Twain impression, a service in itself.) But the title is, to say the least, misleading.

Perhaps the strangest of all Twain’s many pop-cultural portrayals is his claymation iteration in 1985’s The Adventures of Mark Twain. If it’s been a while, allow me to refresh your memory: A stop-motion Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn and Becky Thatcher have to convince a suicidal, disillusioned Mark Twain not to ram his magical, time-traveling balloon into Halley’s Comet. Along the way, there’s history, some dramatizations of Twain’s work, and more oddness than you could possibly imagine. But you don’t have to take my word for it!

Its creator, Will Vinton, was apparently inspired by the quote in which Twain prophetically predicted the year of his death:

I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year (1910), and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’

Personally, I love that this film exists. Did it terrify me as a child? Yes. (But what didn’t? This was the era of Return to Oz and The Black Cauldron.) But it’s also a respectful, albeit bizarre, introduction to the works of Twain that gives children a lot of credit. You wouldn’t, maybe, want to use it as the basis for a paper—that’s why God made Val Kilmer—but as a testament to the author’s enduring appeal, it’s noteworthy.

Poets on Photography

The latest issue of Aperture magazine focuses on the relationship between literature and photography. The editors were kind enough to share the feature below, in which four poets discuss some of their favorite photographs. It appears in Aperture magazine #217, Winter 2014, “Lit,” as “Collectors: The Poets.”

© Sergio Larrain/Magnum Photos

John Ashbery

Sergio Larrain, Boulevard Saint-Germain, Before the Deux Magots Café, 1959.

I lived in Paris mostly from 1955 to 1965. This photograph, called Boulevard Saint-Germain, Before the Deux Magots Café, Paris 1959, is by Sergio Larrain. The Café Deux Magots was a favorite hangout of mine, at least when I was flush enough to afford it. I could conceivably have been there when the picture was taken. The photograph sums up beautifully the atmosphere of Paris on a rather chilly autumn afternoon, with well-dressed and well-behaved tourists sipping their café exprès and two fashionable cars, a sports car and a sedan. The three people chatting around the sports car are almost crystallizations of Parisians of that now distant era. The young man at far left, with his back to the camera, is an iconic silhouette of the time, with pleasantly rumpled clothes and both shoes planted firmly on the pavement. I keep this card tucked into a picture frame over my desk to remind me of the past in all its melancholy variety.

Photographer unknown.

Ann Lauterbach

The Fellowship Photograph (Portrait of Ludwig Wittgenstein), 1929.

I live in an old schoolhouse, built in 1885, in Germantown, New York. It has a large room with south-facing windows. Along the walls, above wainscoting, at about waist height, there is a very narrow, slightly indented shelf that, I am told, once held chalk. It now supports my collection of poetry chapbooks and the occasional postcard portrait of writers: Proust, Samuel Beckett, and this startling one of Ludwig Wittgenstein, known as The Fellowship Photograph, taken by an unknown photographer. It was sent to me some years ago by the poet Mónica de la Torre, with a note about a piece of mine she was publishing in the Brooklyn Rail. For so many years, postcards stitched us to one another and to the world! The Wittgenstein photograph is unsettling; it’s as if he can barely see out from his mind’s fervent activity. There’s something eerie about looking back at him, into his uncomfortable, intelligent eyes, and thinking about the silence that every photograph compels us to acknowledge. I think about this silence often, and the indifference of images to it, and the ways in which captions try, but ultimately fail, to undermine it. Wittgenstein thought a lot about the relationship of silence to words, which is probably why so many poets cherish his writing. He is very good company.

![217MAG400_Poets[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1418418197i/12782123._SX540_.png)

Courtesy of David Alexander

Richard Howard

David Alexander, Dogs and Hydrant, 2014.

I have lived with this photograph taken by the artist David Alexander for the last five years. It consists of a repetitive frieze of three horizontal rows of the same alternating pair of dogs’ faces beneath a slender horizontal strip of what is too severely cerulean to be an indubitable sky. The two dogs’ multiplied faces stare straight ahead, interrupted only on the lower right corner of these repeating posters by four identical placards of an oddly shrimplike image which eclipses all but the sable ear tips of one puppy and the even sabler nose and chin of the other. In front of the dogs is an alluring fire hydrant which offers a curiously practical attraction to the multiple pairs of dogs. Considering the shiny wet surface in which the hydrant stands, it is possible, even likely, that all the poster dogs have already taken advantage of the opportunity.

Courtesy Argos Films

Ben Lerner

Stills from Chris Marker, La Jetée, 1962.

Chris Marker’s La Jetée is composed entirely of stills—save for one brief shot of a woman opening her eyes. This image—the last shot in the photomontage before it briefly becomes a “motion picture”—is a photograph on the verge of becoming film, a flickering between media and their distinct temporalities. I’ve had various images of the image: a cellphone capture of it from a screen, a page in the book version of La Jetée—and what I find most haunting about the photograph is that I always feel her eyes are about to open, to look at me. All photographs I can think of are in the past tense, even if it’s the instant past of Instagram—except for this one, which I feel like you have to be careful not to wake.

John Ashbery is the author of more than twenty volumes of poetry. He has been the recipient of a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and a MacArthur Grant, among many other honors.

Ann Lauterbach received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1986 and a MacArthur Grant in 1993. Her most recent book is Under the Sign. She teaches at Bard College.

Richard Howard, as you can tell, is a devoted dog lover as well as a teacher and translator, notably of works by Baudelaire and Barthes. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1970 and a MacArthur Grant in 1996. His latest book of poems, A Progressive Education, was released this fall.

Ben Lerner is the author of three books of poetry, and the novel Leaving the Atocha Station. His second novel, 10:04, was released in September.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture #217. Reprinted with permission.

The Year in Review (and in Orbit), and Other News

The Cocos Fire, San Diego County, May 15, captured by a DigitalGlobe satellite. Image via Slate

“Time and again we hear about a new desire for the real, about a realism which is realistic set against an avant-garde which isn’t, and so on … It seems to me meaningless, or at least unproductive, to discuss such things unless, to borrow a formulation from the ‘realist’ writer Raymond Carver, we first ask what we talk about when we talk about the real. Perhaps we should have another look at the terms ‘the real,’ ‘reality’ and ‘realism.’ ”

On David Lynch’s paintings and drawings: “Lynch has long been the American director with the most direct pipeline to his unconscious—his graphic work suggests the doodles of an extravagantly disturbed child … The implied or explicit subject of these paintings is often arson, rape, or murder, but in Lynch’s work, merely existing is a violent affair.”

The year in satellite images: snapshots from DigitalGlobe’s WorldView-2 and WorldView-3 satellites captured erupting volcanoes, protests, melting glaciers, music festivals, and, most chillingly, wildfires—from 480 miles up, a landscape on fire looks more like it’s covered in blood.

Slava Polunin is Russia’s “best-known artistic clown,” and now he’s taking his act on the road. “His reaction to events, he insists, is best seen in his portrayal of the human condition … He thinks Samuel Beckett ‘had the human condition about right, but there is no need to be miserable about that.’ Audiences watch a mime character preparing for suicide with a noose—and end up cheering a finale involving a ticker-tape storm and giant colored balls, against a haunting, electronic soundscape.”

“In a poll conducted by Variety in August, the five most influential celebrities among Americans age thirteen to eighteen were all YouTube stars. Ryan Higa, KSI, Smosh, Jenna Marbles, and other YouTubers with equally absurd names were all more popular than notable old person Leonardo DiCaprio. The highest-ranking movie star, Jennifer Lawrence, lagged well behind someone named PewDiePie, a Swedish twenty-five-year-old who films himself cracking jokes while playing video games. His videos have been seen more than 6.5 billion times, making his the most viewed channel of all time—bigger than Beyoncé, bigger than Bieber.”

December 9, 2014

Art Amnesty

Why are some people artists while others are not? Was Joseph Beuys an idiot when he said everyone is an artist? Do artists think they are a cut above the rest of us? Are the arts a good in themselves, or is it much, much, more complicated than that?

Many artists delude themselves into believing that they are promising, productive artists when they would live much more fulfilled and useful lives engaged in proper employment. I PROMISE NEVER TO MAKE ART AGAIN provides a baptism of necessary real life and allows artists to “Get Real.” Ditch a life of poverty and precarious self-employment! Don't miss a life-changing opportunity.

Art: It’s had a good run.

You know, there was the Venus of Willendorf. And the Dutch Masters—remember them?—and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, all with some very nice work. And Picasso! Who could forget Picasso?

But we’ve come to the end of the line, more or less. The art world may continue apace, with its Jeff Koonses and its Damien Hirsts, but most artists know only suffering. And to these artists, Bob and Roberta Smith have issued a clear message: go home, clean off your paintbrushes, and do something meaningful with your lives.

“The personal journey for most artists starts with enthusiasm and joy,” Bob and Roberta have said, “and ends, if the artist does not have huge success, in embarrassed children taking their dead parents’ work to the dump.”

It would be better just to quit, no? Bob and Roberta—who are, in fact, one person, named Patrick Brill—aim to ease your transition into the world of utility. If, in surrendering your artistic impulses, you have any leftover artworks in need of prompt disposal, take them to MoMA PS1, where, through next March, Bob and Roberta are hosting the Art Amnesty project. It’s an almost unconscionable bargain: you bring them art, they throw it away. Hell, they’ve got dumpsters right there in the courtyard! And if you’re the sentimental type, they’ll let you exhibit your work one last time in the gallery. You know, before it’s unceremoniously destroyed.

All you have to do is promise never to make art again.

You’ll even get a complimentary badge that says I AM NO LONGER AN ARTIST. (No word on whether this offer applies to writers yet—I’m hoping the answer is yes.)

Got a work of art that isn’t yours, but that still demands immediate eradication? No problem! Bob and Roberta Smith will take it off your hands and ensure that it rots in some landfill somewhere, and you’ll sign a pledge that says I NEVER WANT TO SEE THIS WORK OF ART AGAIN.

All the details are here. With the New Year around the corner, it’s high time you asked yourself: Isn’t it time you gave up?

New York’s First Daily Newspaper

Here’s the front page of the inaugural edition of the American Minerva (“Patroness of Peace, Commerce and the Liberal Arts”), New York’s first daily newspaper, published on December 9, 1793, from Wall Street, “nearly opposite the Tontine Coffee House.” It aimed to contain “the earliest intelligence, collected from the most authentic sources,” and it’s full of those long s letterforms (ſ) that look like lowercase fs and were by then not long for this world.

Its editor was Noah Webster, a Federalist who wanted to discourage the French influence in the U.S. His first “address to the public” covered nearly the entire front page. (Must’ve been a slow news day.) “Newspapers,” he wrote,

from their cheapness, and the frequency and rapidity of their circulation, may, in America, assume an eminent rank in the catalog of useful publications in a great degree, supersede the use of Magazines and Pamphlets. The public mind in America, roused by the magnitude of political events and impatient of delay, cannot wait for monthly intelligence. Daily or at furthest weekly communications are found necessary to gratify public curiosity.

The American Minerva ran for 744 issues between 1793 and 1796. It was bought out and eventually became the New York Sun, which was around until 1950.

Click to enlarge.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers