The Paris Review's Blog, page 632

December 22, 2014

The Beauty of Code

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

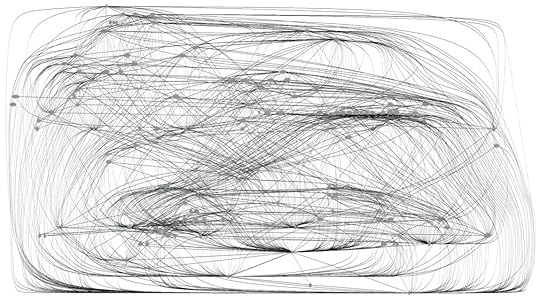

Dependency diagram (Image via TheDailyWTF)

This is what ugly code looks like. This is a dependency diagram—a graphic representation of interdependence or coupling (the black lines) between software components (the gray dots) within a program. A high degree of interdependence means that changing one component inside the program could lead to cascading changes in all the other connected components, and in turn to changes in their dependencies, and so on. Programs with this kind of structure are brittle, and hard to understand and fix. This dependency program was submitted anonymously to TheDailyWTF.com, where working programmers share “Curious Perversions in Information Technology” as they work. The exhibits at TheDailyWTF are often embodiments of stupidity, of miasmic dumbness perpetrated by the squadrons of sub-Mort programmers putting together the software that runs businesses across the globe. But, as often, high-flying “enterprise architects” and consultants put together systems that produce dependency diagrams that look like this renowned TheDailyWTF exhibit. A user commented, “I found something just like that blocking the drain once.”

If that knot of tangled hair provokes disgust, what kind of code garners admiration? In the anthology Beautiful Code, the contribution from the creator of the popular programming language Ruby, Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto, is an essay titled “Treating Code as an Essay.” Matz writes:

Judging the attributes of computer code is not simply a matter of aesthetics. Instead, computer programs are judged according to how well they execute their intended tasks. In other words, “beautiful code” is not an abstract virtue that exists independent of its programmers’ efforts. Rather, beautiful code is really meant to help the programmer be happy and productive. This is the metric I use to evaluate the beauty of a program.

December 19, 2014

Staff Picks: Crayoned Cartoons and Computer Corruption

James Hoff, Stuxnet No. 1, 2014, chromaluxe transfer on aluminum, 30" × 24". Image via BOMB

I caught Susan Te Kahurangi King’s exhibition at Andrew Edlin Gallery before it closes this weekend, and I’m glad I did. I'd never heard of her, but her cartoony, figurative drawings have affinities with work by some of my favorite artists: Gary Panter, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Barry McGee, and Peter Saul. King hails from New Zealand (her middle name is Maori), and has drawn prolifically since childhood. The show contains work she made when she was only about a decade old; these drawings aren’t notable for their technical prowess but because their imagery and composition carry over into the drawings she made when she was older. That is to say, these are forms and arrangements that have preoccupied King for much of her life. Tightly packed configurations of Bugs Bunnies and Donald Ducks and other figures—sometimes colored with bright crayons, other times left as outlines—are frequently cloistered on one side of the paper, resembling fragments of ancient tablets. Most works in the show are from the sixties and seventies; King mysteriously stopped drawing in the eighties and has only now taken it up again. Here's hoping this is only the first of many exhibitions to come. —Nicole Rudick

For a few months now I’ve been irritating my friends, colleagues, and loved ones by using one of the artist James Hoff’s contaminated ringtones. Call me up and anyone nearby will hear a version of Apple’s standard iPhone Marimba ringtone infected with the ILOVEYOU virus, a computer worm from 2000. This sounds like exactly what it is: broken. A familiar motif corrupted with static, screeches, and squelches, and so rendered at once annoying and unsettling. (“Your phone is fucked,” a guy once told me on the street, his voice suggesting that a close relative of mine had just died.) The infected ringtones are part of Hoff’s vast, viral canon: he’s reduced a stunning variety of images and songs to code and then reconstituted them with corrupt code inside. “My newer work definitely draws from everyday phenomena inside the background noise of pop culture,” Hoff told BOMB earlier this year: “computer viruses, ear-worms, and syndromes. All of these are illnesses, broadly speaking. Viruses, like art, need a host, preferably a popular one … Like traditional illnesses, computer viruses travel through networks of communication or trade … A few years back I felt the need to try and to reconcile my creative process with the language of code, which is touching everything these days. It’s to the point where I don’t even know if you could say that this table right here (knocking on table) doesn’t have code underneath it.” It’s hard to think of an artist today engaging more profoundly with the seamy underbelly of our technocracy—and as hacking scandals continue to make headlines, his work only becomes more relevant. —Dan Piepenbring

Blanche McCrary Boyd was my creative-writing advisor at Connecticut College. For more than twenty-five years, she’s collected scores of young writers—many of us inattentive, hungover, and horny—vying for a seat in her twelve-person fiction seminar. To call her a deft storyteller would be an understatement; Blanche would routinely fill our three-hour sessions with tales of addiction, recovery, and everything in between. I picked up her second novel, The Revolution of Little Girls (1991), in an attempt to recapture the awesome terror of her voice—and it did not disappoint. Blanche’s familiar tone is unavoidable, especially so in her protagonist, Ellen Burns. A delightfully wry and impulsively adventurous southern belle, Ellen stumbles headlong into an affair with another woman. But not before spending her early years stealing fish, getting drunk on spirits of ammonia, and hypnotizing a dean or two at Duke. Ellen is charming when graceless and wonderfully nasty when need be. A definite mainstay in lesbian literature, Blanche’s novel is a wild trip of insight, uncomfortable giggles, and old-fashioned wisecracks. —Alex Celia

Peel

From the cover of Louisa May Alcott’s An Old-Fashioned Girl.

The past, as we know, is another country, and from the age of four or so, I wished passionately for dual citizenship. What old-fashioned meant, I couldn’t even have told you. But for most of my early life I worshipped the idea devoutly. To me it meant inheritance, placement, being part of something larger.

I think I envisioned this vague past as a world where I belonged. Other children were kind and wholesome; clothes were strange and modest; I was not ridiculous. Paradoxically, my communion with the past made me wholly ridiculous. Sporting bloomers to the third grade has rarely been a road to modern popularity.

As might be clear, my family had no particular veneration for ritual, but I still cleaved to the idea of holidays as a tradition-steeped idyll. I baked and decorated and played carols, and my homemade gifts were very strange. The primary reason for this is that I got all my ideas from a series of vintage books with names like Let’s Make a Gift! and Fun and Thought for Little Folk, and the youngest of them dated to the late 1930s. As a result, my parents were treated to pen wipers and blotters, a pipe cleaner “embroidered” with the word Father (my dad did not smoke a pipe), and, on one particularly lackluster occasion, a “brush for invalids” that involved wrapping a stick in a piece of flannel so the bedridden individual did not need to wash her hair.

Sometimes the anachronistic nature of these projects made it difficult to find the necessary materials. The gifts section of the American Girls Handy Book was particularly frustrating in this regard: I still remember trying—and failing—to find pieces of scrub brush on which to mount “fairy dancers” (these skittle across the piano top as one plays) or “a piece of pith taken out of a dried cornstalk” with which to fashion a Miss Nancy doll.

Around twelve, I moved my base of operations to the kitchen. The results here were weird, too. Obviously I used only vintage recipes, and since these were often vague to the point of inscrutability—and I had no idea what a piece of molasses candy or a fondant-stuffed date was supposed to taste like—the results were frequently disgusting. But to me they were that hazy and magical thing: old-fashioned. And as such, they were ambassadors of a dreamworld.

I like to think I have outgrown my nostalgia, if indeed that is the word for my condition. I have normal clothes and friends and know something about actual history. If you asked me, I’d probably say I was over my belief in a golden age. Yet, for the past few years, I have given away candied orange peel. I know no one gets too excited about it. But I was once told that my great-grandmother always made candied orange peel for Christmas, and as such the idea took on the aura of the sacrosanct. No one ever said they particularly liked her candied orange peel, or that they remember it fondly. Just that she made it. And somehow, that has always been enough for me.

Ghosts on the Nog

The great English tradition of Christmas ghost stories.

One of John Leech’s illustrations for A Christmas Carol, 1842.

I’ve long thought of Christmastime as a season of mostly pleasant intrusions: thirty or so days of remembering to tend, checklist style, to the latest pressing bit of Yuletide business that comes racing back to you. The well wishes. The trip to the Home Depot. The seasonal ales.

This is the Fezziwig side of Christmas, that portion that makes you look up the word wassail when you encounter it and think, Ah, that would be fun. But what of the darker elements of Christmas—and what of Christmas for those people who enjoy making merry most years but may have hit upon a bit of a tricky patch? What succor of the season might they find at the proverbial inn?

Having experienced both sides of Christmas, there is but one constant I am aware of that serves you well both in the merriest of times and in the darkest: the classic English Christmas ghost story. You’d think Halloween would be the holiday that elicits the best macabre stories, but you’re going to want to check that opinion and get more on the Snow Miser side of the equation. Time was the English loved to scare you out of your mind come December, but in a fun way that resulted in stories well afield of your typical ghost story outing.

If you’re into ghost stories, you probably know that M. R. James is held as the master by most. His thing was to write a tale for Christmas, invite some of his fellow Eton dons and favored students into his rooms, and read it over candlelight after everyone had been plied with eggnog. Readings for the season—but not really of the season. There’s not a lot of actual Christmas in James’s stories.

Writers of ghost stories, James included, love to make authoritative lists about what makes such stories work. They offer spectral prescriptions that, as you might gather, rarely hit upon the same guidelines, and then they tend to violate these notions within their own work. But I like the spirit of that endeavor—a naughty/nice list for the spooky crowd—and as someone who devours Christmas ghost stories in the happiest of years and who turns to them, too, at those Christmases when the glimpsed mistletoe kisses of new lovers are akin to sprigs of holly jabbed through the temple, I have some ideas on what you want when it’s time to settle in with your eggnog, dim the lights, and turn some pages.

The first key to a Christmas ghost story is a convivial atmosphere. People in these stories are well fed, they’re often hanging out in groups, you feel like you’re hanging out with them, and you do not wish to leave any more than they do. It is cold outside but warm in here, and it’s time to rediscover that sense of play that so many of us adults lose over the years, and which, when we are fortunate, we remember to rediscover at Christmas.

Next, a game might be proposed, say, a game of telling stories. Then comes the terror. The status quo is infused with a sensation of something being a touch off, chuckles give way to shared, uneasy glances that maybe this isn’t all merrymaking. But this isn’t the terror of Lovecraft or of impending doom or the horror that indicts our fundamentally base natures. It’s a rather more pleasing terror—the ghosts, even when they mean to avenge themselves upon us, also seem to have dipped into the nog a time or two, with their own playfulness in evidence. Sure, they can kill you, but they do so with a joke or two at the ready. These are the short days of the year, and a weird admixture of pagan habits and grand religiosity obtains. There is also booze. People didn’t have TVs: people drank, people got to telling tales, someone told a tale and someone tried to tell a bigger one, and then, lo, we got a whole ghost story Christmas tradition.

But even if you’re into this stuff, there’s a decent chance you’ve not read any of these oft-overlooked Christmas baubles, stories which have always made me grateful for their company, blending themselves to my mood and needs and wishes in ways that nothing else quite has. They’re also dead good fun. So ladle out some perry or mead—or just grab a Bud Light—and allow me to recommend these ghostly tidings.

“Between the Lights,” by E. F. Benson (1912)

This tale is set on Christmas Eve and looks back on the one the year before, when our host had a vision of primal, shack-entombed beasts advancing upon him as he sat out on the lawn and watched his wife and a good friend play croquet. The creatures advance, paralysis has set in, and it is by a Christmas mercy that the hold is relinquished. Daytime haunts can seem even less natural than the midnight variety, and this one proves portentous when the vision is actualized, after a fashion, before we all collectively shudder and call for more mulled cider, the tale complete.

“The Kit-Bag,” by Algernon Blackwood (1908)

We’ve all been in the position of racing off for the Christmas holiday, fretting that we’ve forgotten to pack something. In this story, a law clerk—whose boss just cleared a murderer—is packing what he believes to be the travel bag said employer has lent him. But the holidays can be misleading, and one man’s Tumi luggage can be another’s sack to lug around a severed head in. Again, there’s that notion of warmth, of looking forward to things—our man wishes to chat up the ladies back in the lodge on his ski holiday—and affability. You want this guy to be okay. Alas, he’s ripped open from stem to stern and bleeds out as the clock chimes in Christmas. Only kidding, dear reader. A very good thing about a great Christmas ghost story is that you will be frightened, but the new people you have come to care about tend to live to see another Christmas.

“A Strange Christmas Game,” by J. H. Riddell (1863)

Even spook-story enthusiasts tend not to know that a goodly amount of Victorian ghost fiction was written by women. Maybe the majority of it. Mrs. J. H. Riddell was one of the best ghost story writers of her time—period—and in “A Strange Christmas Game” we have that idea of play again, only now it is the ghosts who are trying their hands at sport. Cards, as it were. A brother and sister have recently taken possession of a house willed to them, and the demise of their benefactor plays out like some horrible, woebegone mummer’s act.

“Christmas Re-union,” by Sir Andrew Caldecott (1912)

This one comes from a volume called Not Exactly Ghosts, an apt summation of Caldecott’s approach—the things in his story could kind of happen on their own. Again, we begin at a family holiday party, but there’s a guest who’s a prick. Everyone is pleased when he leaves, and wouldn’t you know it? He heads out at the same time as Santa Claus, or rather, the Santa the family thinks it hired to put on an act for the kiddies. The prickish guest, we learn, did his uncle a bad turn once upon a time, and this Father Christmas knows about it—worse still, he’s an avenging Father Christmas. Santa is the ghost in this story, maybe, or not. Because Santa could just be pissed-off kin. You get to riddle it out for yourself.

“Smee,” by A. M. Burrage (1931)

My personal favorite. At this party, we’re playing a form of hide-and-seek in which the seeker advances upon the hider and says, “It’s me,” which, uttered quickly and breathlessly enough, becomes smee. It’s Christmas Eve, this is a big old rambling house, but one tiny problem: there’s an extra player who does not number among the guests. A sort of moral: downing the nog and playing hide-and-seek can make you want to pull a Scrooge. Reading this story—like drinking too much nog—would be enough to have you cancel Christmas next year. If only it wasn’t so much fun to get messed up on the stuff.

Colin Fleming writes for Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, and the Boston Globe. He is a regular contributor to NPR’s Weekend Edition and Newstalk Ireland’s The Tom Dunne Show. He is working on a memoir, I Am Not Like You: A Broken Man’s Attempt to Write His Way Out of Hell One Story, Book, Deadline, and Note-to-Self at a Time, and a Beatles book, Same Band You’ve Never Known. His next book, The Anglerfish Comedy Troupe: Stories from the Abyss, comes out in August.

Made in Hollywood

Budd Schulberg’s centennial.

Budd Schulberg (center) at the Watts Writers’ Workshop, ca. 1965.

“My problem,” novelist and screenwriter Budd Schulberg told Kurt Vonnegut at the close of a 2001 interview published in these pages, “is that I’m not going to live long enough to do all the different things I want to do. My time is beginning to run out a bit.” Then eighty-seven years old, Schulberg—whose credits include the Oscar-winning script for On the Waterfront (1954), a handful of widely acclaimed novels, a Hollywood memoir, a collection of short stories, a biography of Muhammad Ali, and volumes of essays and magazine articles on boxing—was working with Spike Lee on a screenplay about the epic 1930s battles between heavyweight world champions Joe Louis and Max Schmeling and collaborating with Ben Stiller on a film adaptation of his best-known novel What Makes Sammy Run? (1941). Eight years later, he bid his final farewell before either of these projects could be realized. He would have turned one hundred this year.

Early last month, I attended a two-day celebration of his centennial in Hanover, New Hampshire, at Dartmouth College, from which Schulberg graduated in 1936 and whose Rauner Special Collections Library holds his papers. The event began with the unveiling of a library exhibition—“Budd Schulberg and the Scripting of Social Change,” which runs through the end of next month—charting the writer’s numerous engagements with political events that spanned much of the twentieth century. As editor of The Dartmouth, the college’s daily paper, in 1935, he covered a quarry workers’ strike in Proctor, Vermont, anticipating the preproduction research he would undertake on the mafia infiltration of the dockworkers’ union for On the Waterfront. In 1965, greatly distressed by the Watts riots in Los Angeles, he founded the Watts Writers’ Workshop the day after the city’s curfews were lifted; he went on to edit, in 1967, From the Ashes: Voices of Watts. A few years later, with his former Workshop collaborator Fred Hudson, Schulberg established the Frederick Douglass Creative Arts Center in New York City.

Although a native son of New York, where he was born Seymour Wilson Schulberg on March 27, 1914, Budd was raised in Hollywood. His father, B.P. Schulberg, worked as a studio executive—he was, at one time, the head of production at Paramount—and his mother, Adeline, ran a literary agency. He grew up playing cops and robbers on the studio lot, knew the sets like they were part of his own living room, and worked as a publicist at Paramount while still in his teens. He considered himself to be, as he put it in a piece for the New York Times in 1939, of “the Motion Picture Generation.” Starting out at Los Angeles High School, he spent his senior year at Deerfield Academy and then headed for Dartmouth, where he studied sociology and English. Together with his childhood friend Maurice Rapf, who also grew up in Hollywood and went to Dartmouth, he visited the Soviet Union in 1934, where he was inspired by Maxim Gorky’s speech on socialist realism delivered at the first Soviet Writers’ Congress. After graduation, he moved back to Hollywood to work as a script doctor and joined the Communist Party of the United States.

Over the course of his life, Schulberg never shied away from controversy or professional reprisals. An ill-fated 1939 collaboration with F. Scott Fitzgerald on the script for Winter Carnival—which was filmed at Dartmouth and strands of which he would later fictionalize in his novel The Disenchanted (1950)—brought him back to Norwich, Vermont, directly across the Connecticut River from campus. There, he wrote quite possibly the most wicked satire of Hollywood ever produced: What Makes Sammy Run? The story chronicles the ruthless ascent of a newspaper copyboy to power-hungry movie mogul, waging a kind of “blitzkrieg against his fellow men” along the way. Rereading the novel today, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to imagine how there could ever have been Sidney Falco of Sweet Smell of Success or even Jordan Belfort, the so-called wolf of Wall Street, without there first having been a Sammy Glick—that turbocharged Horatio Alger from New York’s Lower East Side. After the scandal Sammy unleashed in the movie colony, Louis B. Mayer suggested to Schulberg père that his son should be deported. “Where the hell are you going to deport him,” B.P. is said to have replied, “Catalina Island?”

Schulberg left Hollywood for Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and, later, Long Island, but his life retained the high drama of a Hollywood screenplay. In the aftermath of World War II, working for the Office of Strategic Services, he prepared photo testimony for the Nuremberg Trials and rounded up Leni Riefenstahl to serve as a witness. He named names at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing in 1951 (he’d abandoned the Communist Party while writing Sammy), but he also wrote one of the sharpest indictments of political demagoguery and media manipulation in his screenplay for Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1958). He traveled to Cuba after the revolution to interview Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, to whom he showed considerable sympathy, and sometime in the seventies, while vacationing with his then-wife, Geraldine Brooks, in Puerto Vallarta, he agreed to a tequila-fueled midnight brawl with John Wayne over the putatively treasonous nature of Sammy (his wife broke up the fight before Schulberg was able to prove whether or not he could have been a contender). He covered the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Zaire for Newsday, and, owing to the quality of his sports writing, he was inducted to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2003.

One of the high points of the two-day Schulberg celebration was the public screening of the documentary Hollywood Renegade: The Many Lives of Budd Schulberg (shown in rough cut), which was produced and directed by his son Benn and shot by veteran documentarian Albert Maysles. The film features lengthy interviews with blacklisted writers Walter Bernstein and Arthur Laurents—both of whom obstinately refuse to forgive Schulberg for serving as a friendly witness before HUAC—alongside more affectionate reminiscences by Tony Curtis, Patricia Neal, Bert Sugar, Spike Lee, and Ben Stiller, who also serves as executive producer of the film. At a time when the motion picture business is mired in blockbuster franchises and endless sequels and remakes, the consistent freshness of Schulberg’s work feels all the more urgent and compelling, not to mention his commitment to innovation. “Don’t tell that story over again,” he admonished Hollywood in 1939. “I know it by heart.”

Noah Isenberg directs the Screen Studies program at the New School and is the author, most recently, of Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins. His writing has appeared in Bookforum, The Nation, the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. He’s currently at work on a new book, Everybody Comes to Rick’s: How ‘Casablanca’ Taught Us to Love Movies.

The Hattifatteners at Bedtime, and Other News

Tove Jansson‘s Hattifatteners.

On a new biography of Tove Jansson: “She discovered lesbian love … Biographies invariably contain a section on her sexuality and this one is no exception. Its insight that the creatures in Moominland called the Hattifatteners ‘resemble a wandering flock of penises or condoms’ is a point to ponder when reading aloud at bedtime.”

What are the most important questions to ask ourselves when we read? “What is the emotional atmosphere behind this narrative? That’s the question I suppose I’m asking—and what is the consequent debate arising from that atmosphere?”

The Chinese term for “effortless action” is wu wei. You’ll soon see it in self-help texts—and why not? Striving to try less hard may, in fact, be very self-helpful. “Wu wei is integral to romance, religion, politics and commerce. It’s why some leaders have charisma and why business executives insist on a drunken dinner before sealing a deal.”

“A raucous, Sherlock Holmes–themed pantomime called ‘Mrs. Hudson’s Christmas Corker’ might not sound like the most highbrow play that London has to offer. But if you sample enough of the mulled wine being served in the foyer beforehand, you begin to see it differently.”

Matisse’s cutouts are now—and not for the first time—the toast of the art world. But when he made them, he wasn’t so sure: “Matisse worried that working with cut paper was cheating—a shortcut to painting—and he kept it a secret. ‘It is necessary not to say anything about this,’ he wrote to his son Pierre, in 1931.”

December 18, 2014

Happy Haneke

A still from Haneke’s The White Ribbon, lovingly altered by Luisa Zielinski.

Three simple facts:

1. It’s the third night of Hanukkah.

2. Our new issue features the Art of Screenwriting No. 5, an interview with Michael Haneke.

3. Haneke and Hanukkah are pronounced in very nearly the same fashion.

A disinterested observer might chalk this up to mere coincidence. That observer would be correct. Still, you may consider, during these eight nights of gift-giving, capitalizing on the Haneke/Hanukkah near-homonym and presenting your loved one with a subscription to The Paris Review, starting with our Haneke issue—just forty dollars for a year’s supply of fiction, poetry, interviews, and art, including a postcard announcing your gift with a personal message. They make a great present for aspiring writers, who should, in the words of William Kennedy, “read the entire canon of literature that precedes them, back to the Greeks, up to the current issue of The Paris Review.”

And our thanks to Luisa Zielinski (who interviewed Imre Kertész for the quarterly last year) for sending along the highly appropriate greeting above.

Toast

Photo: Ken Hawkins

I was told not long ago that a certain prominent New York publication has put a moratorium on features about the death of local institutions; otherwise, they’d be running such features constantly. And the sad truth is, there is a sameness to the narrative. Neighborhoods change, rents rise, developers swoop, venerable places close. It’s a story so familiar that it tends, nowadays, to inspire sadness rather than outrage.

These stories also pose certain questions. What makes something "iconic”? Just because a place is old, does that automatically make it an institution? What if standards have slipped, and a restaurant or bar is a pale shadow of its former self? And, of course, the ultimate test: sentiment aside, how often do you actually go there? In the end, the arguments are moot. Good or bad, beloved or forgotten, everything is going. The Metro section reads like an obit page.

You could spend your life going only to sepia-toned places for purely charitable reasons. What kind of a life this would be, I can’t say—probably a melancholy one, filled with pricks of secret, guilty relief when some of the spots are put out of their misery and the civic-minded patron is let off the hook.

I just had a last lunch at a coffee shop that’s being ousted by new landlords. My grandfather used to have lunch there. Of course, my grandfather didn’t care about food. So long as he could get a quick sardine on rye toast and get back to work, he was happy. That, of course, is the point; it’s the loss of everyday, affordable things that hurt most. That’s when a world vanishes.

Walking back from lunch, my friend and I admitted the truth: the matzo ball soup had been insipid, the kasha varnishkes woefully underseasoned, the matzo brie bland, and the alleged Reuben a mere pile of tough corned beef and sauerkraut blanketed with barely melted cheese, and with nary a drop of Russian to improve the situation. The lunch had been bad.

Did it matter? I asked. Did it render its loss less sad?

“No,” my friend said. “It doesn’t change the nature of the basic, systemic problem. After all, there’s no such thing as a perfect victim.”

The Kitchen Show

How to host an art exhibition in your kitchen.

Photo: Gun Westholm

During my time at high school and university in Kreuzlingen and St. Gallen, I traveled around Europe looking at art, visiting artists, studios, galleries and museums. I knew that what I wanted to do in life was to work with artists, but I had yet to produce anything. I was searching for a way to make a contribution. What, in this art system, could be a first step, and above all, how could I be useful to artists? I began to think about all the innovative, large-scale museum shows I had seen and whether it was really possible to do something new, combining all the networks I had been enmeshed in, the entire European Thinkbelt. One conviction I had was that it could be interesting to do something smaller, after the gigantism of some of the 1980s art scene which seemed unsustainable after the crash of 1987.

Dependency on endless growth, as the end of each cyclical bull market always teaches us, is unrealistic. I studied political economy with a professor named H. C. Binswanger, who directed the University of St. Gallen’s Institute for Economics and Ecology. Binswanger was examining the historical relationship of economics and alchemy, which he made as interesting as it (at first) sounds outlandish. His goal was to investigate the similarities and differences between aesthetic and economic value, most famously in a book he later published called Money and Magic (1994). At the core of modern economics, Binswanger believed, is the concept of unlimited, eternal growth; he showed how this brash concept was inherited from the medieval discourse of alchemy, the search for a process that could turn lead into gold.

In his childhood, Binswanger had been fascinated by the Faust legend. During his studies he discovered that the invention of paper money in Goethe’s Faust was inspired by the story of the Scottish economist John Law, who in 1716 was the first man to establish a French bank issuing paper money. Even more strikingly, the Duke of Orleans got rid of all his alchemists after Law’s innovation, because he realized that the availability of paper money was more powerful than all attempts to turn lead into gold. In Money and Magic, Binswanger traces the deep association between paper money, alchemy and the concept of eternal growth that underlies modern economics.

Binswanger also connected the economy and art in a novel way. Art, he points out, is based on imagination and is part of the economy. But the process of money creation by a bank is connected to imagination, because the money is printed as a countervalue for something that doesn’t yet exist. So the invention of paper money is based on imagination, or a prospective sense of bringing into being something that has yet to exist. A company imagines producing a good and needs money to realize this, so it takes out a loan from a bank. If the product is sold, the “imaginary” money that was created in the beginning has a countervalue in real products. In classical economic theory, this process can be continued endlessly. Binswanger recognizes that this endless growth exerts a quasi-magical fascination.

In his book Binswanger pointed out that the moderation of growth has become a global necessity: he produces a way of thinking about the problems of rampant capitalist growth.

Binswanger encouraged me to question the mainstream theory of economics, and to recognize how it differs from the real economy. The wisdom of his work is that he recognized early on that endless growth is unsustainable, both in human and planetary terms, but instead of rejecting the market wholesale, he suggests ways to moderate its demands. Thus the market does not have to disappear or be replaced, but can be understood as something to be manipulated for human purposes, rather than obeyed.

Another way of interpreting Binswanger’s ideas is as follows: for most of human history a fundamental problem has been the scarcity of material goods and resources, and so we have become ever more efficient in our methods of production, and created rituals to enshrine the importance of objects in our culture. Less than a century ago, human beings through their rapacious industry made a world-changing transition: we now inhabit a world in which the overproduction of goods, rather than their scarcity, is one of our most fundamental problems. Yet our economy’s growth functions by inciting us to produce more and more with each passing year. In turn, we require cultural forms to enable us to sort through the glut, and our rituals are once again directed towards the immaterial, towards quality and not quantity. Perhaps that is a reason for the shift in our values, from producing objects to selecting amongst those that already exist.

During the days I attended Binswanger’s lectures, I thought about the kinds of exhibition I could make. At the time, two shows, both of them in a domestic environment, were on my mind. In 1974, Harald Szeemann had created a small exhibition about his grandfather, who was a hairdresser, in his apartment in Bern. The second was in 1986 in Belgium, where curator Jan Hoet had hosted a show called Chambres d’Amis (Rooms of Friends) in a very intimate, non-institutional environment: he commissioned more than fifty artists to make works for an equal number of private apartments and homes around Ghent. It was a way of making a sprawling exhibition that also took visitors on a domestic tour of the city. And then both Fischli and Weiss and Christian Boltanski suggested to me that perhaps I was looking too hard, that the solution could be in my own flat, as with the Edgar Allan Poe story “The Purloined Letter.” And we began to think, and an answer occurred to us: my kitchen.

The answer was pragmatic. I didn’t have access to an exhibition space in a gallery or a museum, of course, but I did rent an old flat in St. Gallen. I never cooked. I never even made tea or coffee because I always ate out. The kitchen was just another space where I kept stacks of books and papers. This was exactly the feature that Fischli, Weiss and Boltanski had independently noticed. The non-utility of my kitchen could be transformed into its utility for art. To do a show there would mix art and life, naturally. The idea took shape very quickly. Perhaps because the show’s concept was pithy and fitting for me, artists immediately responded to it. Fischli and Weiss thought it would be great to transform my non-kitchen into a functional kitchen. Then the exhibition would actually produce reality, they joked. Boltanski, meanwhile, liked the thought of a hidden exhibit in the kitchen. As art was conspicuous for its moments of high visibility in the late 1980s, he was attracted to the idea of something more intimate.

I embraced both ideas. Boltanski created a very hidden exhibit: he installed a projection of a candle, visible only through the vertical crack between the cabinet doors under the sink. The candle was like a small miracle where you would normally find the garbage or cleaning supplies. Above the sink was a big cupboard, and here Fischli and Weiss installed a sort of everyday altar, using oversized, commercially packaged food from a restaurant supply store. Everything was giant: a five-kilogram bag of noodles, five litres of ketchup, canned vegetables, huge bottles of sauces and condiments. The installation had an Alice in Wonderland sense about it. It produced a sense of wonder by giving an adult a child’s perspective. All of a sudden reality was, for the adults who beheld this oversized display, almost like it is for children. The only item we ever opened was a chocolate pudding. The rest of the pieces were kept intact as readymades, and eventually returned to the artists, who kept them in their basements—until they began to rot.

Hans-Peter Feldmann decided to make an exhibition within the exhibition in my refrigerator. He found six eggs made out of dark marble, which he placed in the egg rack in the fridge door. And then he placed a board with small feathers on it on the top shelf, setting up a charming visual rhyme in and amongst the few jars and cans that had somehow found their way into even my most under-utilized fridge. Frédéric Bruly Bouabré produced a kitchen drawing with a rose, a cup of coffee and a sliced fish. Richard Wentworth placed a square mirrored plate on top of cans of food. No one attempted to make a spectacular intervention—instead they preserved the function of the kitchen, while subtly adding to it.

Many features of the kitchen show mark my work as a curator to this day. For instance, artists shared in all tasks relating to my exhibitions, not just their individual pieces: Richard Wentworth named the kitchen show World Soup, while Fischli and Weiss took the exhibition photographs. Secondly, I continue to curate exhibitions in people’s houses, which brings a different focus and a special intimacy. To give a very different example, I created an exhibition at the neoclassical architect Sir John Soane’s house in 1999.

Numerous are the posthumous museums and memorials devoted exclusively to one artist, architect or author and designed to preserve or artificially reconstruct the namesake’s original working or living conditions. Much rarer are the museums conceived by artists in their lifetimes as a Gesamtkunstwerk and preserved as such. Sir John Soane’s Museum is a case in point. In 1833, four years before he died, Soane established his house as a museum and negotiated for an Act of Parliament to ensure its preservation after his death. The house is a complex accretion of hallways, windows, hangings, plinths, mirrors and innumerable objects, with unexpected views around every corner. Soane’s holdings fall into four main categories: antique fragments, paintings from Canaletto to Hogarth and Turner, architectural drawings (such as Piranesi’s), and Soane’s own work in the form of architectural models and drawings.

The artist Cerith Wyn Evans once told me: “I was always very stimulated and inspired by the relationships, the interstices in Sir John Soane’s Museum, the conversations that are happening between various narratives, various objects and these extraordinary vistas that you come upon by accident and then you catch a reflection of yourself. It is an incredibly complex, stimulating place, and no one visit is ever the same as the next.” After a while, the idea of an exhibition began to take shape, and, in the course of the following two years, it crystallized in conversation with Margaret Richardson, the Curator of the Museum.

Although Sir John Soane’s Museum has regular opening hours and attracts some 90,000 visitors a year, it has acquired a reputation primarily by word of mouth. The paradox of a well-guarded and yet public secret as well as the permanent pull between visibility and invisibility are the considerations that motivate Cerith Wyn Evans, whose intervention on the staircase was almost invisible. The work slid into the existing context as it subtly changed the sound of the bells. Steve McQueen created a sound montage that revealed itself only at second glance. To bring the various elements of the exhibition into a cohesive whole, each of the artists contributed to the greater picture: Richard Hamilton designed the poster, and each artist created a postcard that was on sale in the museum. The works on view in the exhibition were numbered but not labelled, in keeping with the way Soane displayed his collection. Each visitor was given a foldout leaflet, conceived by Cerith Wyn Evans, with plans by Christopher H. Woodward. There were no didactic panels or sound guides, and visitors moved where they wished through the rooms, encountering unexpected works of art in unexpected places. Cedric Price created symbols for the show and gave a lecture in the old kitchen entitled “Time and Food,” and Douglas Gordon created the title of the exhibition: Retrace Your Steps: Remember Tomorrow. Like the works in World Soup, the works in Retrace Your Steps had a sense of playfulness, and both shows were self-organized—instead of beginning with a master concept or plan, they grew organically. Exhibitions should develop a life of their own, more like a conversation between curator and artist than an arrangement of their work to suit a pre-existing idea. The experience with Cerith Wyn Evans at Sir John Soane’s Museum led to an ongoing series of house museums. Next came an exhibition with Pedro Reyes at the Casa Barragán, the architect Luis Barragán’s home in Mexico City. After that I curated an exhibition at the poet Federico García Lorca’s house in Granada, produced by Isabela Mora, followed by another show produced by Isabela Mora at the Lina Bo Bardi house in São Paulo, Brazil.

Excerpted from Ways of Curating by Hans Ulrich Obrist with Asad Raza. Published by Faber and Faber, Inc. an affiliate of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Hans Ulrich Obrist. All rights reserved.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a Swiss-born curator and writer. He is the codirector of exhibitions and programs and the codirector of international projects at the Serpentine Galleries, London. His previous books include A Brief History of Curating; A Brief History of New Music; Everything You Always Wanted to Ask About Curating But Were Afraid to Ask; Sharp Tongues, Loose Lips, Open Eyes, Ears to the Ground; Ai Weiwei Speaks, and nearly thirty volumes of his Conversation Series of interviews with contemporary artists.

Amiri’s Green Chim Chim-knees Growth Tribe

Amiri Baraka, Maya Angelou, and Toni Morrison at James Baldwin’s funeral, 1987. Photo: Thomas Sayers Ellis

Thomas Sayers Ellis’s poem “Polo Goes to the Moon”—an elegy for the bounce-beat go-go music pioneer Reggie Burwell—appeared in The Paris Review No. 209 earlier this year. Now he’s recorded a spoken-word version in “Amiri’s Green Chim Chim-knees Growth Tribe,” part of a tribute to Amiri Baraka to be released next year by Heroes Are Gang Leaders. Give it a listen above.

After Baraka died in January, Ellis and his frequent collaborator James Brandon Lewis formed Heroes Are Gang Leaders, a group of poets and musicians. They recorded the album over three six-hour sessions. Ellis calls it “a signifying groove head-nod to Mr. Baraka,” influenced by Thelonious Monk and A Tribe Called Quest.

The text of “Polo Goes to the Moon” is below.

POLO GOES TO THE MOON

for Reggie Burwell

There’s been

a lot of talk,

lately, as to whether

or not America

actually went

to the moon.

The non-believers

say there’s no

weather in space

—no humidity, no wind, no rain,

only empty pockets

and crank shapes.

Craters, big ass

asteroids, black holes.

They say waving

our arms, all at once,

is as false as the flag

and We, the people, percussively agree:

Astronaut-Bouncing

looks jive-phony, unless,

of course, you think of the moon

as a snare drum

—half, eclipsed, full,

and consider, as Polo did,

the percussive

nature of gravity,

the forcible way the earth,

like a party, pulls

a body, every body

back to it … every time

some symbol crashes

or the rototoms,

like satellites,

get too-hype and someone

jumps up, as Polo did,

beyond the

regular “lock” of

solar system

like a short, well-barbered

meteor, hurled

into the divine orbit

of coma … beyond the limitations

of all things earthly,

including the notion

of nation, and its local,

ingrown extension: going National.

The whole time

Polo was in the air,

he was in total control

of his own ounce

of lunar sleep,

replacing the handcuffs

around Saturn

with open hi-hats.

The whole time

he was on

life support,

alphabetized,

removing vowels.

Heroes Are Gang Leaders:

Thomas Sayers Ellis, Poet

James Brandon Lewis, Saxophone

Luke Stewart, Bass

Ryan Frazier, Trumpet

Janice Lowe, Piano

Warren “Trae” Crudup, Drums

The question “Vowels?” asked at the end by Mariahadessa Ekere Tallie

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers