The Paris Review's Blog, page 631

December 25, 2014

River of Fundament

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

*

On the set Matthew Barney’s singular new film.

Matthew Barney’s studio, the birthing place of some of the biggest and most ambitious art of our time, sits in an industrial New York netherzone by the East River in Queens. A couple blocks down is a garage for cast-off food carts in states of obliteration and disarray. On the streets stroll workers whose sturdy coats solicit calls to 888-WASTEOIL, for the service of all waste-oil wants and needs. Alongside the studio the mercurial river flows, its current changing direction several times a day.

Inside are forklifts to move things like six-ton blocks of salt and sculpturally abetted Trans Ams. Football jerseys hang on a wall, including one for the fabled Oakland Raiders center Jim Otto (his number, 00, puts Barney in mind of extra-bodily orifices). A staff of a half dozen studio hands oversees projects of enterprising kinds, from building and bracing large architectural oddities to disrupting and destroying sculptures and letting objects rot.

It was here that Barney completed River of Fundament, a new epic film project premiering this week at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, with a running time of nearly six hours (including two intermissions) and passages that play as extravagantly abstracted and absurd. The film was inspired by Norman Mailer’s 1983 novel, Ancient Evenings, set in ancient Egypt and invested in stages of reincarnation that come after death. The story would not seem to be eminently filmable.

But River of Fundament is not exactly a film. It draws on a series of site-specific performances and elaborate happenings—live actions related to the project date back as far as 2007—and all of them, however cinematically presented in the end, fit as sensibly within the traditions of theater and opera. Shoots lasted for days, doubling as rituals or séances, with characters performing for an audience that would come to be part of the work. Read More >>

Love in a Cold Climate

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

Photo: Sebastian Dooris

I moved to Greenpoint, in North Brooklyn, on the heels of a breakup, and although I lived there for years, in my memories it is always somehow winter. While I was hardly a pioneer in the neighborhood—a recognizable mumblecore actor lived one fire escape away—ten years ago it was still a far cry from today’s full-on Girls-level gentrification; friends still griped about taking the unreliable G train to come visit, and more than one said that the rent had better be pretty cheap to justify the schlep. It was.

To those who know the area, this was just off of Monsignor McGolrick Park, a twelve-minute walk from the Nassau Avenue station. At first glance the apartment was unprepossessing, but after I had pulled up the stained carpet, painted the walls a vivid blue, found a copper leaf sculpture at a thrift store, and sewn a gaily-patterned bark-cloth curtain to separate the bedroom, I fancied it was cheerful, in a vaguely retro-modern way. There was also a fire escape large enough for a table and chairs, not to mention a few pots of nasturtiums and some basil in the summer, even though, again, my primary memories involve snow.

I had chosen the neighborhood because it was one of the few where I could both afford to live alone on my shopgirl salary and also feel safe walking alone at night. But I had not been living there long when I met M., and he kind of just moved in by osmosis. It was never a formal arrangement, but I didn’t like going to his roommate-filled bachelor pad three trains away, and we were young enough that this sort of thing seemed normal. Read More >>

December 24, 2014

Open Ye Gates! Swing Wide Ye Portals!

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

*

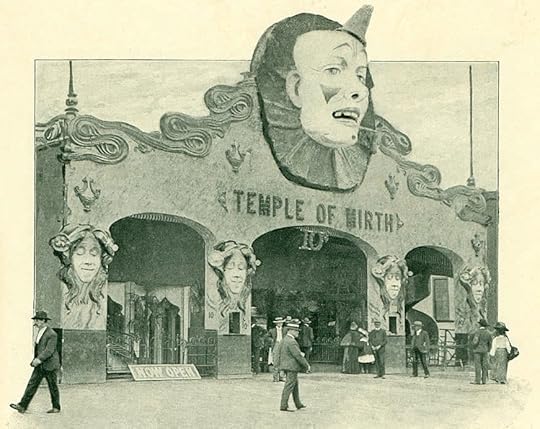

St. Louis’s unforgettable 1904 World’s Fair.

Temple of Mirth, 1904 World’s Fair.

I hand the attendant a fifty-cent piece and watch him drop it into the automatic turnstile, itself a marvel. Behind me, the murmur of moneychangers, the swish of gored skirts tapering to white shirtwaists. Beyond that, the din of St. Louis. My sack suit rustles as I stride ahead. I’m crossing the threshold of an impossible city: a manicured wonderland of symmetrical lagoons winding through sculpted gardens studded with allegorical statues. In the distance loom the massive palaces of learning, their Beaux-Arts façades harkening back to Ancient Rome and heralding a future brighter than the hundred thousand incandescent lights that line them against the night. The words of Exposition President David R. Francis ring in my ears—Open ye gates! Swing wide ye portals! Enter herein ye sons of man, and behold the achievements of your race! Learn the lesson here taught and gather from it inspiration for still greater accomplishments!—and I step into the Fair.

* * *

St. Louis is a city of gates that do not normally swing wide. The urban private street, or “private place,” is believed to be a local invention, dating to the 1850s. Private places are owned by their residents, who typically build and maintain the road, median, sidewalks, curbs, street lighting, and—most crucially—gates. Some gates were utilitarian, imposing, and plain; others were small castles, complete with clock towers, fountains, statues, gaslights, and gatehouse apartments that caretakers (and, later, college students) lived in until the 1980s. Private places offered a refuge from the ever-booming city, a world apart. Some have been razed, their gates uprooted, the neighborhoods now troubled by crime; many still stand, pockets of wealth and privilege, with boards of trustees that oversee matters of law (historic preservation, landscaping) and etiquette (street parking, book clubs, Easter egg hunts).

Nearly two years ago, when my wife and I were moving to town and looking for an apartment, we were taken aback: everywhere, gates, gates, gates. Gates that lock and unlock according to byzantine schedules publicized only to residents (thus thwarting commuters and anyone else who might try to cut through the neighborhood). Gates that open by remote control. Rolling metal gates with yellow hazard signs. Gates built for carriages that now barely fit a car. Even in less-rarified neighborhoods—with weeds in the lawns and unwashed economy sedans on the street—at the end of the block might stand a pitiful sawhorse made of white PVC pipe. A symbol that speaks to the natives. Private Street: Not Thru. Private Street: No Public Parking. No thru traffic. Private neighborhood. No smoking beyond this gate. Private. No trespassing. Keep Out.

Read More >>

Here’s Pie in Your Eye

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

*

Pieing for fun and profit.

“I used to throw pies for a living.”

The story usually elicits a good chuckle or two. It’s the perfect gambit when dinner-party conversation lags—a legendary prank executed long ago in my rascal past, a kind of April Fools’ joke.

But what my audience never knows is this: they’re talking to a guy who once commanded a hit squad of domestic terrorists that carried out a slew of public attacks in broad daylight and got away with it.

Well, mostly. An enraged crowd of Trekkies nearly stomped me to death after I’d boldly gone and pied William Shatner, their beloved Captain Kirk, at a Star Trek convention. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Read More >>

Talk About Beauties

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

*

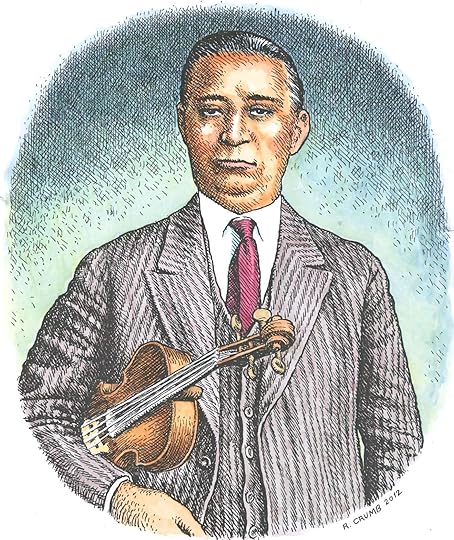

The lost recordings of a phantom musician.

Alexis Zoumbas, illustrated by R. Crumb.

The text printed on the label of the Greek 78-rpm disc translated as “Alexis Zoumbas ~ violin, accompanied by young men of the Epirot village of Politsani.” Its significance, and the meaning behind its very existence, stymied all speculation. No one had heard what was etched into these grooves since they’d been pressed—the Greek title for the song was untranslatable, and the recording itself was undocumented, hushed into being for no perceptible reason other than to come into my possession.

A week before this record arrived at my post office, I’d finally untethered myself from Zoumbas and his recorded legacy. After two years of focused inquiry, I’d finished work on Alexis Zoumbas: A Lament for Epirus, 1926-1928, a collection of his recordings. I’d let go. But any comfort I found in that was lost when this disc came into my life.

The 78 rpm record was the dominant medium of auricular permanence and commerce for more than fifty years. These fragile vessels of sound are coveted by collectors who, like myself, have developed a precise yet vaguely sexual phraseology to describe their physical condition. This Zoumbas disc, for instance, was in excellent condition, but with a tight hairline crack and a slightly enlarged spindle hole.

And what of its artist? Alexis Zoumbas was a phantom musician, a violinist. Born in the hinterlands of Epirus, Greece, in 1883, he immigrated to New York City in 1910 and died practically unknown in Detroit in 1946. The myth surrounding his life maintained that he’d fled Greece after murdering his landlord, and that he himself had been gunned down by a jealous lover. Drawn in by his music and intrigued by these stories, I become obsessed with his life. I traveled to his home village, Grammeno, to interview his two surviving nephews, Michalis and Napoleon Zoumbas, both retired musicians in their eighties. In Ioannina, the capitol of Epirus, I unearthed biographical documents; in the U.S. I found immigration and naturalization papers, as well as a draft card and a death certificate. This trail of evidence, dispersed across continents, corrected the narrative of this powerful musician’s life. He did not kill his landlord, and he wasn’t offed by a jilted lady friend—those were apocryphal stories created to elevate his musical status and cultural legacy. Zoumbas had entered into the elite mythical realm reserved for more well-known American prewar musicians like the Delta bluesman Skip James and the Appalachian banjoist “Dock” Boggs, majestic artists surrounded by imaginary rows of corpses, stacked like cordwood, coolly dispatched in their dreams and in the stories told about them. Read More >>

December 23, 2014

The Missing Borges

Seven years ago, a stolen first edition of Borges’s early poems was returned to Argentina’s National Library. But was it the right copy?

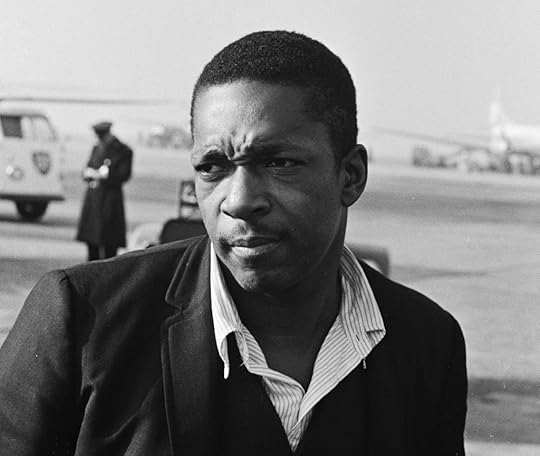

Jorge Luis Borges in 1963. Photo: Alicia D'Amico

The world of rare books and manuscripts is full of intrigues, betrayals, and frauds. Alberto Casares has lived in this world for decades; as the president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of Buenos Aires, he’s an expert on the subject. He’s got the physique du rôl: a gray, messy beard; a soft body; an intense and wary look.

A few months ago, Casares was offered a seventeenth-century original edition of Don Quixote for one million euros. He recognized it as a well-known forgery from the nineteenth century, worth no more than €200,000. The seller took it away, determined to find a more unsuspecting client, and Casares was left alone with the melancholy of having lost something that was never his to own.

What would some people give to own it? Casares told me, “Bibliographers are willing to commit crimes to follow their mad desire to own things.” He was thinking of a former client, Daniel Pastore, a collector of rare books and first editions, heir to a pharmaceutical fortune and owner of Imago Mundi, Buenos Aires’s most elegant antiquarian bookshop, which closed a few years ago after a succession of international scandals involving Pastore.

Casares was annoyed and fascinated by Pastore, who was eighteen the first time he walked into Casare’s bookshop. He was handsome, rich, likeable, and learned—a good client. But he was also pedantic; he claimed to know more about rare books than Casares. Sometimes he did. But not when it came to Jorge Luis Borges. Read More >>

Paper Trail

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

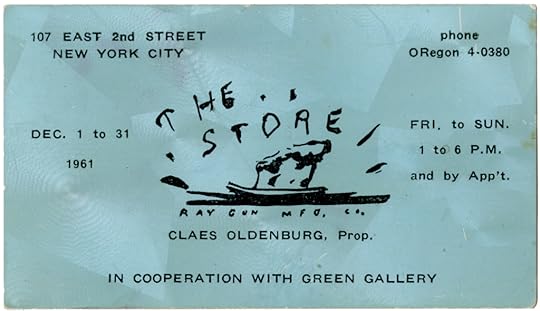

The invitation card for Claes Oldenburg's Store, New York, 1961.

Three years ago, PPP Editions published a limited-edition book called 100 Fanzines / 10 Years of British Punk 1976–1985. I have a copy and keep intending to give it to any number of friends who know more about the Clash, the Mo-dettes, or Attila the Stockbroker than I do, but I haven’t yet handed it over. I certainly wasn’t a fixture of the Thatcher-era punk scene, but I nonetheless feel nostalgic when I look through the book. The cover of Verbal Warfare no. 1, from 1981, contains the line “Beware of the serpent that twines around the cross … his body, the living dead at their production lines,” and I notice that it’s written in a script that resembles my sister’s eighth-grade cursive. I’m transfixed by the the ratty hand-drawn graphics and raw, energetic designs, not to mention the silliness and badassery of titles like Ignorance of the Unborn, Terminal Illiteracy, Surrey Vomet, and Raisin ’ell (number 10 is the special “This issue sucks!” edition). I also love the zines’ materiality: the staples in the bindings, the softly foxed corners, the smudges, visible erasure marks, and toner streaks. The idea that these are at once mass-produced publications (you can almost feel a phantom photocopier heat coming off the page) and rare objects—always already ephemeral—is fascinating.

The very notion of ephemera is curious: objects of little value that weren’t meant to be preserved but whose vulnerability, I imagine, appealed to someone. Political buttons, business cards, seed packets, and train timetables—scrappy artifacts that otherwise would have been lost to the dustheap. Even ephemera’s subcategories—like “fugitive materials” and “gray literature”—are suitably mothy and eccentric. In the art world, potential ephemera is everywhere: small-edition artist books, exhibition posters, flyers, announcement cards, invitations, press releases. The Museum of Modern Art Library, in New York, houses an extensive archive populated by such materials. A photograph of the files at MoMA QNS shows reams of folders that resemble medical records, though a bit of feathery orange fluff peeping out from one folder suggests something less sober. Through its sheer volume, the archive offers a minihistory of art and of individual artists.

David Senior, a bibliographer at MoMA Library, curated an exhibition around the archive; “Please Come to the Show” was on view last year in New York and earlier this year at the Exhibition Research Centre in Liverpool. It must have been fun digging through all the files and (re)discovering canon-adjacent materials like Claes Oldenburg’s blue, slightly stained business card/invitation to The Store; Nancy Spero’s pugnacious, textual invitation to “Torture of Women”; and an announcement, addressed to Frank O’Hara, of the premier of Warhol’s film Empire (admission: two dollars). Read More >>

The Jimmy Winkfield Stakes

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

*

A racetrack in obsolescence.

Photo: Ilya Lipkin

Every year on the third Monday of January, the Aqueduct Racetrack, in South Ozone Park, Queens, runs a six-furlong race in honor of Jimmy Winkfield. The choice of date, Martin Luther King Day, is not accidental. Of Winkfield’s many accomplishments, which include winning the Russian Oaks an incredible five times for Czar Nicholas II, he is best known as the last black jockey to run a winner in the Kentucky Derby, in 1902.

To be black in the world of horse racing was no easy thing in the early part of the twentieth century. Winkfield, born in Kentucky, had enjoyed a storied career in Russia and France, but when he returned to America he was forced to enter a reception held in his honor through the hotel’s service entrance, with the bellhops and the kitchen staff.

Because of the raw January weather, attendance at the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes is usually rather sparse compared to the bigger events at the height of the racing season. This year, my older brother Ilya and I saw the race completely on a whim—we thought it might be fun to trek out to the Aqueduct like we used to when we were younger. Back then, if the weather was fine, our father would drive us to the track out in Ozone Park, a favorite destination for the unattached men in the neighborhood. Edik from the dry cleaners down the street was a fixture there, as was Pavel, the bartender at the Pennant Sports Bar on Northern, and Parsons, whose brother was an orderly at the elder-care facility where our grandfather died. To me, gaining admission to that world of working men was no less exciting than the races themselves. I watched with great interest as they quaffed beer and studied the odds on the board and cursed when they invariably lost their money. Being a bit older, Ilya had a better sense of what was actually going on. He nagged Pavel until the bartender showed him how to decipher the near-hieroglyphic racing form. The one time my father let him place a bet, we won eighty dollars. It proved to be a red-letter day, because that same afternoon, I fed a carrot to Cigar, the Hall of Fame thoroughbred, just before the first big win of his career. (The Aqueduct now runs a race in his honor as well.) Read More >>

December 22, 2014

An Absolute Truth: On Writing a Life of Coltrane

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

A few years ago I found a used, first-edition hardcover of Dr. Cuthbert Ormond Simpkins’s 1975 book, Coltrane: A Biography, online for $150. I had long admired its feverish, street-pulpy story about the saxophonist John Coltrane, whose powerful music increasingly seemed capable of altering one’s consciousness before he died in 1967, at age forty. Posthumously, the mythology and exaltation of Coltrane, as well as his musical influence, only grew. But by that point, Simpkins had already researched and written Coltrane’s story, expressing an uncompromising, unapologetic black voice rarely found in the annals of jazz before or since.

I forked up the money for the hardback. The dust jacket bears an impressionistic black-and-white painting of Coltrane playing soprano saxophone. The rounded, sans serif font resembles that of Soul Train, the popular TV show that premiered in 1971. On the back cover is a photograph of a young, Simpkins sporting a West African dashiki shirt, a high Afro, thick sideburns, and a beard.

Simpkins’s idea for the book was conceived during his senior year at Amherst, in 1969; he worked on it during breaks from Harvard Medical School in the early seventies. Simpkins possessed no credentials in jazz or literature. The publisher of the original hardcover is Herndon House; quick Google and Library of Congress searches yield no other books from that publisher. There are identical typographical errors in all three editions—first and second hardback, and paperback. (Sarah Vaughan’s name, for instance, is spelled once as “Vaughn,” and Nesuhi Ertegun appears as “Nehusi.”) All indications point to the book having been self-published, the original piece preserved in two later editions. Read More >>

Ditching Dickensian

We’re out until January 5, but we’re re-posting some of our favorite pieces from 2014 while we’re away. We hope you enjoy—and have a happy New Year!

*

Giving the lie to a critical crutch.

Illustration: Robert Ingpen

Copies of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch now bear an impressive gold foil sticker declaring it the “WINNER of the PULITZER PRIZE.” Before that accolade, though, critics had already branded the novel by using and abusing the adjective that’s launched a thousand blurbs—Dickensian. Despite, or perhaps because of, the ubiquity of the word in appraisals of the novel, such assessments are rarely issued without caveats. NPR’s Maureen Corrigan apologetically notes that the term “is one of those literary modifiers that’s overused”; in the New York Times Book Review, Stephen King somewhat ruefully acknowledged that he wouldn’t be the last to employ Dickensian to describe Tartt’s novel. He was right.

For all this critical concurrence, it’s less than clear what we mean by Dickensian, or, for that matter, by any adjective with a particular author at its root. Francine Prose leads her review of The Goldfinch with this very question: “What do people mean when they call a novel ‘Dickensian’?” As Prose notes, a number of answers present themselves—Dickensian can signify sentimentality, an attentiveness to the social conditions, a cast of comically hyperbolic characters, a reliance on plot contrivances, or even simply a book’s sheer length. (I suspect one rarely means the relatively slim A Tale of Two Cities or Hard Times when one labels a novel Dickensian.) In other words, the proliferation of the senses of Dickensian makes one wonder if it, or other such words, are critically useful at all. As Cynthia Ozick has recently complained with regard to Kafkaesque—another perennial—the word “has by now escaped the body of work it is meant to evoke.” Read More >>

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers