The Paris Review's Blog, page 638

December 3, 2014

Marvels and Mysteries

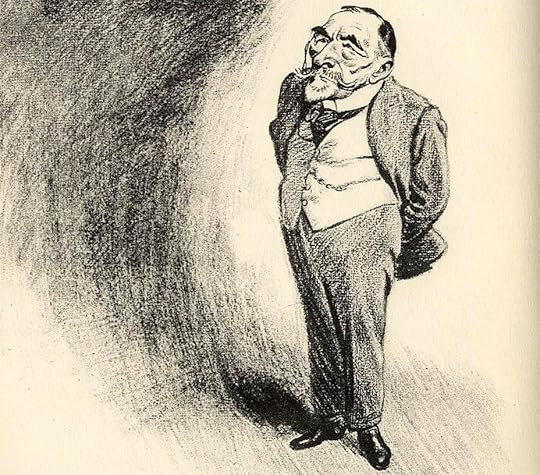

A caricature of Conrad by David Low, 1928.

INTERVIEWER

How would you define fantastic, then?

BORGES

I wonder if you can define it. I think it’s rather an intention in a writer. I remember a very deep remark of Joseph Conrad—he is one of my favorite authors—I think it is in the foreword to something like The Dark Line, but it’s not that …

INTERVIEWER

The Shadow Line?

BORGES

The Shadow Line. In that foreword he said that some people have thought that the story was a fantastic story because of the captain’s ghost stopping the ship. He wrote—and that struck me because I write fantastic stories myself—that to deliberately write a fantastic story was not to feel that the whole universe is fantastic and mysterious; nor that it meant a lack of sensibility for a person to sit down and write something deliberately fantastic. Conrad thought that when one wrote, even in a realistic way, about the world, one was writing a fantastic story because the world itself is fantastic and unfathomable and mysterious.

INTERVIEWER

You share this belief?

BORGES

Yes. I found that he was right. I talked to Bioy Casares, who also writes fantastic stories—very, very fine stories—and he said, “I think Conrad is right. Really, nobody knows whether the world is realistic or fantastic, that is to say, whether the world is a natural process or whether it is a kind of dream, a dream that we may or may not share with others.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Art of Fiction No. 39, 1967

Since it’s Joseph Conrad’s birthday, I went in search of his foreword to The Shadow Line—it was an author’s note, actually, appended to the novel’s second edition in 1920. And Borges’s memories of it are largely accurate: Conrad uses it to mount a defense of “the world of the living,” which “contains enough marvels and mysteries as it is … I am too firm in my consciousness of the marvellous to be ever fascinated by the mere supernatural.”

The Shadow Line, which is now in the public domain, was first published in 1916, when it appeared over the course of two months in Metropolitan Magazine. It tells the story of a young man who assumes the captaincy of a ship in “the Orient.” The ghost of the ship’s previous captain, Mr. Burns, lurks: “His face in the full light of day appeared very pale, meagre, even haggard. Somehow I had a delicacy as to looking too often at him; his eyes, on the contrary, remained fairly glued on my face. They were greenish and had an expectant expression.”

Here’s the author’s note Borges mentions:

This story, which I admit to be in its brevity a fairly complex piece of work, was not intended to touch on the supernatural. Yet more than one critic has been inclined to take it in that way, seeing in it an attempt on my part to give the fullest scope to my imagination by taking it beyond the confines of the world of the living, suffering humanity. But as a matter of fact my imagination is not made of stuff so elastic as all that. I believe that if I attempted to put the strain of the Supernatural on it it would fail deplorably and exhibit an unlovely gap. But I could never have attempted such a thing, because all my moral and intellectual being is penetrated by an invincible conviction that whatever falls under the dominion of our senses must be in nature and, however exceptional, cannot differ in its essence from all the other effects of the visible and tangible world of which we are a self-conscious part. The world of the living contains enough marvels and mysteries as it is; marvels and mysteries acting upon our emotions and intelligence in ways so inexplicable that it would almost justify the conception of life as an enchanted state. No, I am too firm in my consciousness of the marvellous to be ever fascinated by the mere supernatural, which (take it any way you like) is but a manufactured article, the fabrication of minds insensitive to the intimate delicacies of our relation to the dead and to the living, in their countless multitudes; a desecration of our tenderest memories; an outrage on our dignity.

Whatever my native modesty may be it will never condescend so low as to seek help for my imagination within those vain imaginings common to all ages and that in themselves are enough to fill all lovers of mankind with unutterable sadness. As to the effect of a mental or moral shock on a common mind that is quite a legitimate subject for study and description. Mr. Burns’ moral being receives a severe shock in his relations with his late captain, and this in his diseased state turns into a mere superstitious fancy compounded of fear and animosity. This fact is one of the elements of the story, but there is nothing supernatural in it, nothing so to speak from beyond the confines of this world, which in all conscience holds enough mystery and terror in itself.

Perhaps if I had published this tale, which I have had for a long time in my mind, under the title of First Command, no suggestion of the Supernatural would have been found in it by any impartial reader, critical or otherwise. I will not consider here the origins of the feeling in which its actual title, The Shadow-Line, occurred to my mind. Primarily the aim of this piece of writing was the presentation of certain facts which certainly were associated with the change from youth, carefree and fervent, to the more self-conscious and more poignant period of maturer life. Nobody can doubt that before the supreme trial of a whole generation I had an acute consciousness of the minute and insignificant character of my own obscure experience. There could be no question here of any parallelism. That notion never entered my head. But there was a feeling of identity, though with an enormous difference of scale—as of one single drop measured against the bitter and stormy immensity of an ocean. And this was very natural too. For when we begin to meditate on the meaning of our own past it seems to fill all the world in its profundity and its magnitude. This book was written in the last three months of the year 1916. Of all the subjects of which a writer of tales is more or less conscious within himself this is the only one I found it possible to attempt at the time. The depth and the nature of the mood with which I approached it is best expressed perhaps in the dedication which strikes me now as a most disproportionate thing—as another instance of the overwhelming greatness of our own emotion to ourselves.

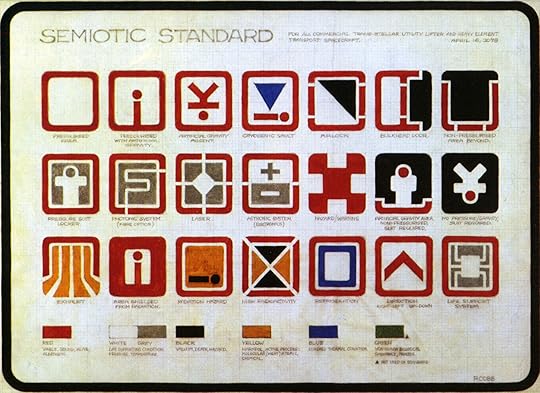

The Iconography of the Future, and Other News

Ron Cobb’s Semiotic Standard for All Commercial Trans-Stellar Utility Lifter and Heavy Element Transport Spacecraft, ca. 1979.

“There remain subjects aside from storytelling that the novel might continue to pursue profitably—subjects that weren’t exhausted in the nineteenth century. A few that come to my mind: interpersonal ethics; the varieties of form conscience takes in individual psyches; the difficulty of getting along with others; the qualities of mind that meaningfully distinguish one person from another … Whatever else it’s done, contemporary life hasn’t obviated these kinds of questions any more than it has rendered the novel incapable of addressing them.”

On Cubism and an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “What happened in Paris in the seven years up to 1914 can be thanked or blamed for almost anything you like in the later art of the century … ”

The Swedes knew how to design a great cemetery: Skogskyrkogården, built in the early twentieth century, fuses the classical and the modernist. “The cemetery showed the twentieth century a way forward. It showed that design could be in touch with the deepest roots of European civilization without being enslaved to old architectural languages … It transcended its time in a way that very few other works of modernism could manage.”

The typesetting of the future: How do sci-fi movies find fonts and visuals that seem believably vatic? Alien, for example, boasts a production design that’s “a perfect example of used-future chic.” It also features an entire iconography designed by Ron Cobb: the Semiotic Standard for All Commercial Trans-Stellar Utility Lifter and Heavy Element Transport Spacecraft.

These are a few of the sex acts no longer legally filmable by UK pornographers: “spanking,” “aggressive whipping,” “urolagnia (known as ‘water sports’).”

December 2, 2014

Marriage Plot

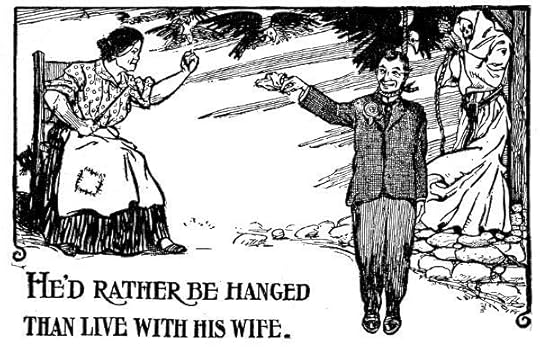

From Twenty Years a Detective in the Wickedest City in the World , a 1908 book—putatively nonfiction—by Clifton R. Wooldridge, “the Incorruptible Sherlock Holmes of America.”

In his agony [Devel] confessed that the only reason he confessed the murder was that he desired to get hanged, and that he preferred hanging to life with his wife. […]

“I desired to be hung,” said Devel, mournfully. “Life is not worth the living, and with my wife it is worse than death. If I had been hanged no other man would marry my wife, and I would save them from my fate. Many times have I planned to kill myself to escape her. That is sin, and I lack the bravery to kill myself, besides. If they will not hang me I must continue to live with my wife.”

Devel states, among other things, that these are the chief grievances against married life in general, and his wife in particular:

She was slender, and became fat and strong.

She was beautiful, and became ugly and coarse.

She was tender, and grew hard.

She was loving, and grew virulent.

She grew whiskers on her chin.

She called him “pig.”

She wore untidy clothes, and her hair was unkempt.

She refused to give him beer.

Her breath smelled of onions and of garlic.

She threw hot soup upon him.

She continually upbraided him because there were no children.

She scolded him in the presence of neighbors.

She refused to permit him to bring his friends home.

She came into his store and scolded him.

She accused him of infidelity.

She disturbed him when he slept in the garden on Sundays.

She made him cook his own dinners.

She spilled his beer when he drank quietly with friends.

She told tales about him among the neighbors, and injured his business.

She served his sausages and his soup cold, and sometimes did not have his meals for him when he came home.

She did not make the beds nor clean the house.

She took cards out of his skat deck.

She talked continually, and scolded him for everything or nothing.

She opened the windows when he closed them, and closed them when he opened them.

She poured water into his shoes while he slept.

She cut off his dachshund’s tail.

These things, he said, made him prefer to be hanged to living with her.

Angry Birds

From The Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1893.

Here’s a scene from Barbara Pym’s 1952 novel Excellent Women, in which the protagonist, Mildred Lathbury, meets Everard Bone’s eccentric mother.

I thought I had better revive the conversation which had lapsed, so I commented on the animals’ heads in the hall, saying what fine specimens they were.

“My husband shot them in India and Africa,” said Mrs. Bone, “but however many you shoot there still seem to be more.”

“Oh, yes, it would be a terrible thing if they became extinct,” I said. “I suppose they keep the rarer animals in game reserves now.”

“It’s not the animals so much as the birds,” said Mrs. Bone fiercely. “You will hardly believe this, but I was sitting in the window this afternoon and as it was a fine day I had it open at the bottom, when I felt something drop into my lap. And do you know what it was?” She turned and peered at me intently.

I said that I had no idea.

“Unpleasantness,” she said, almost triumphantly. Then lowering her voice she explained, “From a bird, you see. It had done something when I was actually sitting in my own drawing room.”

“How annoying,” I said, feeling mesmerized and unable even to laugh.

I draw this to your attention because unpleasantness is a term that is sadly underused. I think of it often, usually in the context of that disgusting, grinning coil-of-feces emoji. (I will not dignify it by using its infantile moniker, as I was discouraged from babyish scatological terminology at an early age and cannot break the habit.) I mean, I don’t sit around being furious, or think about it at unrelated times, but people text with that thing all the time. Indeed, in a recent feature in a fashion magazine, I saw no fewer than two celebrities list this as their favorite, and most frequently used, emoji. (Even I will grudgingly concede that it is versatile, in its inscrutable, repulsive way.)

To me, this is the unpleasantness emoji. This also applies to its animated iteration, which features circling flies. I know its history is an interesting window into tech development (read about it here, if you don’t find the juxtaposition with oral too off-putting) and I’m sure there are far more damning indications of the coarsening fiber of modern society. But it is a small, bad thing. And if I’m being completely honest, I’ve never really understood what it means.

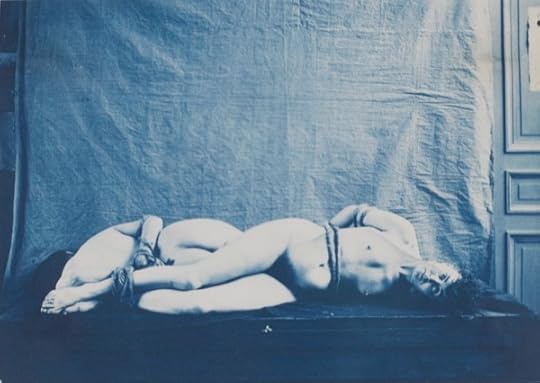

Horrific Practices

Two centuries after the Marquis de Sade, a French exhibition traces his influence.

Charles-Francois Jeandel, Deux femmes nues attachees, allongees sur le cote, between 1890 and 1900; © Musee d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

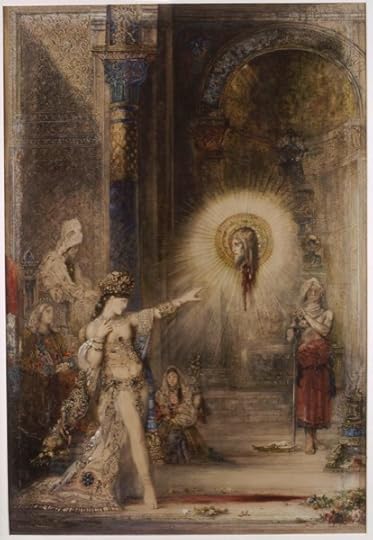

Gustave Moreau, L’Apparition, 1876;

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musee d’Orsay) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

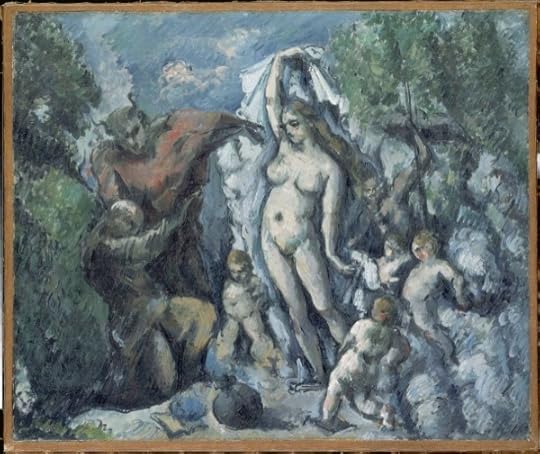

Paul Cézanne, La Tentation de Saint Antoine, 1877;

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musee d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

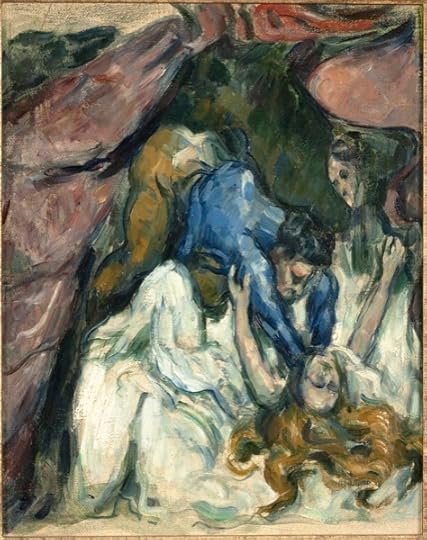

Paul Cézanne, La Femmeétranglée, between 1875 and 1876;

© Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Edgar Degas,Scène de guerre au Moyenâge, 1865;

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Gérard Blot

Franz Von Stuck, La Chasse sauvage, 1899;

© Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Eugène Delacroix, Chasse aux lions (esquisse), 1854; © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Gérard Blot

Auguste Rodin, Minotaure ou Satyre et nymphe, 1885;

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musee d’Orsay) / Adrien Didierjean

Henri Rousseau, La Guerre, 1894; © Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

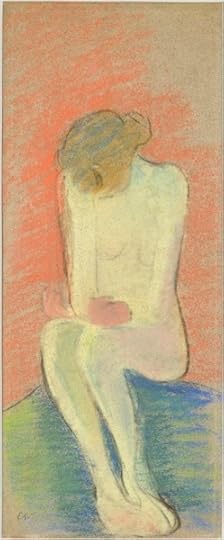

Edouard Vuillard, Figure de douleur, between 1890 and 1891; © Musee d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Fernand Khnopff, Futur, 1898;

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musee d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

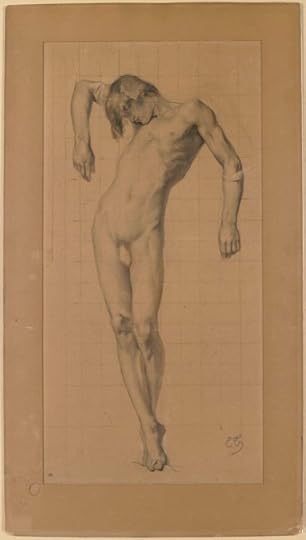

Eugene Thirion, Jeune homme nu, debout, soutenu par les bras;

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musee d’Orsay) / Adrien Didierjean

Virginia Verasis and Pierre-Louis Pierson, Portrait de la comtesse de Castiglione, assise sur une table, le visage en partie coupe, 1865 and 1867; © Musee d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

HonoréDaumier, AndréMarie Jean Jacques Dupin, ca. 1832; © Musee d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Sir Edward Burne-Jones, La Roue de la Fortune, between 1875 and 1883; © RMN (Musee d'Orsay) / Gerard Blot

The Marquis de Sade died two hundred years ago today, on December 2, 1814. To mark the bicentennial, Annie Le Brun, a French academic and writer, has curated a sprawling show in the Marquis de Sade’s name at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The exhibition, “Attaquer le soleil” (“Attacking the Sun”), takes its name from a snippet in The 120 Days of Sodom, and it traces “the revolution of representation” occasioned by Sade’s unbridled lasciviousness: how his ideas about desire and violence seeped into the cultural zeitgeist and into some of the most seminal art created during and after his lifetime.

It seems tenuous, at first, to link Sade to a whole host of artistic traditions—traditions that didn’t necessarily need his help to see society as a holding cell, for teeming vices, impulses, and cruelties, all barely contained by etiquette. During a conference introducing the exhibition, Le Brun clarified her premise: “We didn’t try to illustrate Sade—on the contrary, the propos of Sade illuminates the violence that exists deep within at the moment of mythological, historical, religious painting … everything that Sade addresses was there before, and will of course continue after.” What Sade tapped into, and what’s elevated in the exhibition, is what Le Brun calls the “exaltation of passions” and the “vertigo of excess”—mixed, of course, with “flagrant atheism.”

Sade’s life abounded in fêtes, débauche outrés en petites maisons, liaisons with actresses, dalliances with dancers—carried out throughout his marriage, which lasted from 1763 until an official separation in 1790. His rap sheet includes a scandal with prostitutes (1772) and an abduction of five girls of French and Austrian origin (1775). He encouraged political rioting from his jail cell at the Bastille prison (1789), and his plays, performed at the asylum in which he was later interred, drew such big crowds from Paris that they had to be shut down (1811).

Given her subject’s debauched résumé, Le Brun’s exhibition is suitably orgiastic. It amounts to a “rereading,” she says, “of the history of modernity via a Sadeian prism,” and sure enough, through this prism one begins to see Sade everywhere. The exhibition begins in the dark, in a room where film clips—among them Victor Fleming’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Luis Buñuel’s El, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, and Pasolini’s Salò—are projected on six screens. Starting from this vantage is unexpected—it’s intended to destabilize, simply by “bring[ing] Sade into our era.” From there, the exhibition is a labyrinth of somber, low-lit rooms featuring sculptures, paintings, engravings, photographs, and illustrations, all depicting a remarkable range of iniquity and erotica.

The artists on display are renowned for addressing themes of desire, carnage, fantasy, and other id impulses of that ilk. Gustave Moreau’s elaborate, strange Jupiter et Semelé (1895) readily fits the Sadeian premise. Delacroix’s Chasse aux lions (1834) practically emanates animal heat with indistinguishable silhouettes aswirl in yellow and red. Picasso’s L’Enlèvement des Sabines (1962) is a black, white, and gray frenzy of sinister silhouettes, including an upside-down head, oversized appendages, flared nostrils, and a dagger. And the Austrian artist Alfred Kubin conjures the lurid with startling thematic synchronicity to Sade. His many ink-and-plume drawings from the turn of the twentieth century—Dompteur, Die grosse boa, Schlachtfest, Die Dame auf dem Pferd—are the stuff of nightmares. The marquee artists, like André Masson, Johann Heinrich Füssli, or Paul Delaroche, evoke perverse scenes with ink on paper. And then there are the occasional surprises, notably Paul Cézanne, who evidently had a hankering for the macabre. His La femme etranglée (1875) and L’Enlèvement (1867) make one wonder just what was happening out of frame from all those pear-filled still lifes. To underscore the seamy themes, quotations are posted on the walls throughout—from Nietzsche’s 1887 treatise On the Genealogy of Morality, for instance: “This world has never quite lost a certain odor of blood and torture.”

It’s often held that Apollinaire broke Sade into the mainstream conversation about French literature at the turn of the twentieth century, but Le Brun maintains that he was present well before that: she points out that Sade’s ideas had made headway, albeit clandestinely, only some fifty-odd years after his death, and that his influence is apparent in the very nomenclature of important French texts that followed: Les Fleurs du Mal (Charles Baudelaire, 1857), Les Diaboliques (Barbey d'Aurevilly, 1874), Le Jardin des Supplices (Octave Mirbeau, 1899). These titles articulate what Le Brun calls “a prise de conscience of what lives within: pleasure and pain.”

Le Brun dedicates an entire room to old anatomical drawings, principally by Antonio Serantoni. The exhibition takes in photography, too: Man Ray’s explicit mise-en-scène for William Seabrook in a 1930 gelatin print in which a woman is being tied down, and Hans Bellmer’s images, like La Poupée (a fusion of two lower halves at their waists), which evoke perhaps less sex and more dread. There are twenty-six aristotypes of vaginas photographed in close-up, circa 1880, and an image of a cut-up body found in a suitcase. These images are just some of the uncomfortable exemplars of the deeply problematic gender issue that lurks throughout the circuit. Sade glorified the exploitative sex crime as something decadent: “ferocity is always either the complement or means to lust,” he wrote in La Nouvelle Justine, 1797. Granted, willful female desire is by no means absent here, nor is female savagery—one of the show’s opening pieces, Félix Vallotton’s Orphée depecé par les Ménades (1914), shows Orpheus being dismembered by a coven of women. Still, there’s no refuting that, throughout the ages, women were subjugated to the whims of male impulses a thousand fold more than they instigated their own. The exhibition never communicates any judgment on the long history of the subjugation of women—the viewer has to saddle any discomforts in private.

Throughout this litany of incendiary images, one may think on how this exhibition could have taken any number of shapes—Le Brun herself acknowledges that “certain tableaux could be replaced with others, yes, and often they could be replaced by many others”—yet this version is convincing in its thoroughness. It is a veritable Pandora’s box of ferocity and sexuality, seen through the art-historical canon as well as a freaky, rather extraordinary fringe underbelly. In Aline et Valcour (1789), Sade expressed “the desire to preserve horrific practices that you could not renounce,” and Attaquer le soleil certainly does highlight those irrepressible urges. It’s terrifying to think about what would happen if we exulted in everything that propriety hasn’t beaten out of us. But it’s also exhilarating to see those desires conveyed beyond the imagination.

Sarah Moroz is a freelance cultural journalist and translator based in Paris. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, and Publishers Weekly, among other publications.

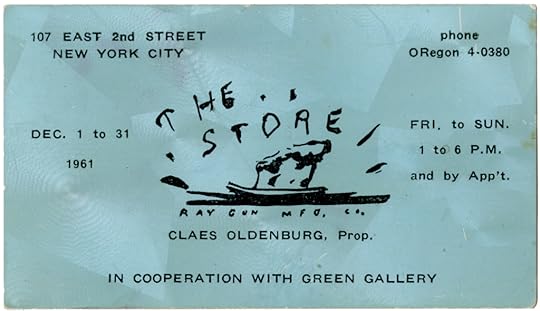

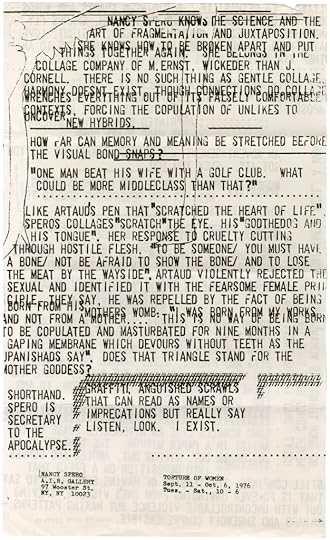

Paper Trail

The invitation card for Claes Oldenburg's Store, New York, 1961.

Three years ago, PPP Editions published a limited-edition book called 100 Fanzines / 10 Years of British Punk 1976–1985. I have a copy and keep intending to give it to any number of friends who know more about the Clash, the Mo-dettes, or Attila the Stockbroker than I do, but I haven’t yet handed it over. I certainly wasn’t a fixture of the Thatcher-era punk scene, but I nonetheless feel nostalgic when I look through the book. The cover of Verbal Warfare no. 1, from 1981, contains the line “Beware of the serpent that twines around the cross … his body, the living dead at their production lines,” and I notice that it’s written in a script that resembles my sister’s eighth-grade cursive. I’m transfixed by the the ratty hand-drawn graphics and raw, energetic designs, not to mention the silliness and badassery of titles like Ignorance of the Unborn, Terminal Illiteracy, Surrey Vomet, and Raisin ’ell (number 10 is the special “This issue sucks!” edition). I also love the zines’ materiality: the staples in the bindings, the softly foxed corners, the smudges, visible erasure marks, and toner streaks. The idea that these are at once mass-produced publications (you can almost feel a phantom photocopier heat coming off the page) and rare objects—always already ephemeral—is fascinating.

The very notion of ephemera is curious: objects of little value that weren’t meant to be preserved but whose vulnerability, I imagine, appealed to someone. Political buttons, business cards, seed packets, and train timetables—scrappy artifacts that otherwise would have been lost to the dustheap. Even ephemera’s subcategories—like “fugitive materials” and “gray literature”—are suitably mothy and eccentric. In the art world, potential ephemera is everywhere: small-edition artist books, exhibition posters, flyers, announcement cards, invitations, press releases. The Museum of Modern Art Library, in New York, houses an extensive archive populated by such materials. A photograph of the files at MoMA QNS shows reams of folders that resemble medical records, though a bit of feathery orange fluff peeping out from one folder suggests something less sober. Through its sheer volume, the archive offers a minihistory of art and of individual artists.

David Senior, a bibliographer at MoMA Library, curated an exhibition around the archive; “Please Come to the Show” was on view last year in New York and earlier this year at the Exhibition Research Centre in Liverpool. It must have been fun digging through all the files and (re)discovering canon-adjacent materials like Claes Oldenburg’s blue, slightly stained business card/invitation to The Store; Nancy Spero’s pugnacious, textual invitation to “Torture of Women”; and an announcement, addressed to Frank O’Hara, of the premier of Warhol’s film Empire (admission: two dollars).

The invitation to Nancy Spero's "Torture of Women," with text by Lucy Lippard, at A.I.R. Gallery, 1976.

I feel about the catalogue to “Please Come to the Show” (published by the British press Occasional Papers) the way I feel about 100 Fanzines: it’s a dusty trunk hauled out of an attic that contains memories that aren’t mine but feel as though they are. I recognize most, if not all, of the artists’ names from seeing their work and reading about them, but these vestiges of exhibitions past look foreign to me—while also looking familiar. Context is the problem. It’s looking at a Warhol Campbell’s Soup Can and then at an actual Campbell’s soup can, and then back at the Warhol. They’re so much alike, but you know that one of them is art and the other isn’t.

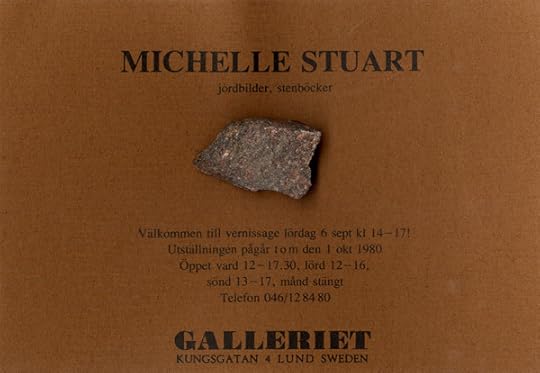

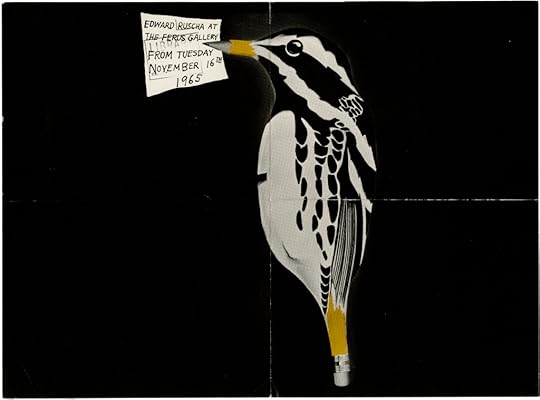

Art ephemera exists in that same gray area: it resembles art, and even depicts art, but isn’t art. That doesn’t stop these posters, cards, and invitations from having the appearance of miniartworks and for being innovative within a genre I didn’t even know existed. Many items in the catalogue aren’t content to remain mere advertisements. On a particularly lovely Ed Ruscha announcement for a show at the Ferus Gallery in 1965, the tail and beak of a black-and-white bird morph into the two ends of a yellow pencil; with his beak, the bird scrawls the show’s information on a small slip of paper. An undated ad for a performance by Judson Dance Theater, designed by Robert Morris, shows two overlapping prints of a right foot, one blurring across the other: the motion of modern-dance steps captured on paper, like Yves Klein’s Anthropométrie or Ana Mendieta’s Body Tracks. The card for a 1980 show, in Sweden, of work by the land artist Michelle Stuart has an actual chunk of rock affixed to it. The invitation has moved beyond mere ephemera; it’s a sculpture in its own right. (What must the mailing costs have been?)

The announcement for Michelle Stuart's show "jordbilder, stenböcker," at Galleriet, 1980.

The announcement for Edward Ruscha's 1965 exhibition at Ferus Gallery.

Conceptual play is at work in a good deal of material. In 1962, a Croatian group of artists known as Gorgona sent out an exhibition invitation that bore only the words IZVOLITE PRISUSTVOVATI, or “Please attend,” printed on it; there was no other information—nothing about, say, where or when the show would be held. It’s rather like Stephen Hawking’s imagined party for time travelers: the invitation is sent out only after the party has occurred, and no one shows up. The Gorgona noninvitation was an influence on Senior’s conception of the exhibition (as well as its title). He cites its “quiet comportment, which coupled cleverly with a clear mischievousness.”

Another prime example of that guiding principle is Robert Barry’s infamous Closed Gallery, from 1962, which consists of invitations to exhibitions in Turin, Amsterdam, and Los Angeles (only the first two are included in the book). God help the poor soul who didn’t read the information closely: “during the exhibition the gallery will be closed.” Collector Herb Vogel called it “without a doubt the greatest piece of Conceptual art that was ever done in the world.”

Occasionally, the artist intrudes on his or her own announcement in more tangible ways. A 1982 postcard for a show of work by David Wojnarowicz carries a handwritten inscription to art historian Lucy Lippard: “Hope you can catch this show. —David.” I don’t know whether she did—by Lippard’s own admission, she didn’t take Wojnarowicz’s art seriously until the late eighties—but it’s a wonderful, touching moment of a now-famous and successful artist (though, sadly, posthumously so) yearning for recognition. It represents an instant in which, Senior says, “now-iconic figures in contemporary art … were decidedly not iconic”; it is “art history as it happened.”

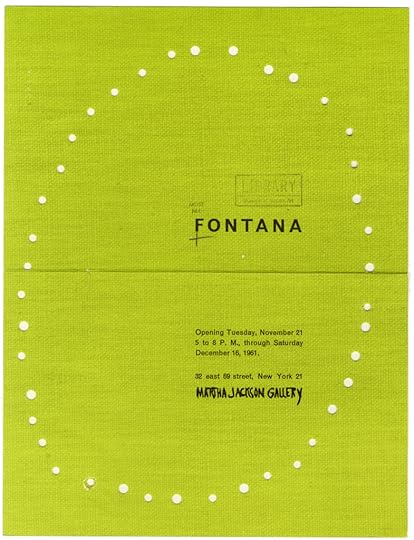

Creatively conceived materials work in tandem with the art they seek to advertise. An announcement for the opening of Lucio Fontana’s show at Martha Jackson Gallery in 1961 is printed on chartreuse, felt-weave paper and is riddled with holes, as though from a hole punch, mimicking the buchi for which Fontana was then best known. On a card for the Dwan Gallery’s 1968 show “Earth Works,” the type is rendered in what looks like sand; its granular form is barely legible against the cardboard-colored paper. Someone, perhaps an overeager assistant or librarian, has written “Conceptual art” in the top corner, only to have it, rightly, marked out.

The announcement for Lucio Fontana's 1961 show at Martha Jackson Gallery.

There are announcements, too, that must have gained value as the work they advertise has become increasingly famous: Dan Flavin’s Four Monuments for V. Tatlin, his first show at Leo Castelli, in 1970; Richard Prince’s provocative Spiritual America (which could be viewed by appointment only), in 1983; Cindy Sherman’s now-iconic Untitled Film Stills, at the Kitchen in 1980.

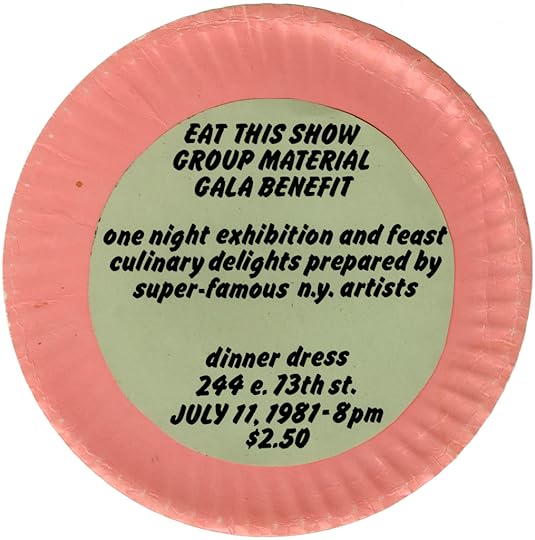

As the eighties take hold, the materials’ inventiveness flags. Designs are occasionally contrived, the jokes less fresh—it can’t be easy to follow on the heels of Barbara Kruger’s hugely influential graphic declarations or Adrian Piper’s gold-embossed, funereal “direct mail advertisement” for Funk Lessons or Group Material’s 1981 invitation for the benefit “exhibition and feast” called “Eat This Show,” which is printed on a paper plate. Still, I expect more from a Mike Kelley invitation, for instance, than a restrained black-and-white design and text with variable kerning. An exception in the closing pages of the book is a quartet of prismatic posters and cards from the early 2000s for events at the collaborative art space General Store, in Milwaukee. The idiosyncratic ethos of the gallery is reflected in the lo-fi aesthetic of the announcements and is a marked departure from the increasing reliance on more conservative and computer-based design work.

The invitation to Group Material's gala benefit "Eat This Show," 1981.

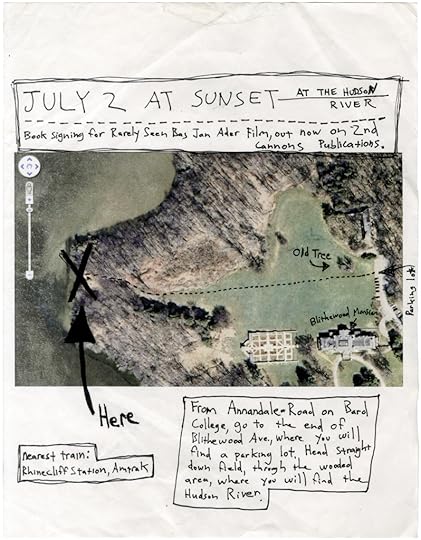

There are far too many excellent invitations and flyers here to have a favorite, but the most intriguing may be those that work as expeditions—invitations not simply to view art but to hunt for it. One of those is an announcement for a 2009 book signing for Rarely Seen Bas Jan Ader Film, by David Horvitz. The flyer reproduces a Google Maps satellite view of a section of land between Bard College’s Blithewood Manor and the Hudson River. Handwritten annotations make it a kind of treasure map, complete with a large X marked “Here.” Attendees were to follow the map’s instructions and meet at sunset at the river. Ader, a Dutch conceptual artist, was famously lost at sea when he set out in a small boat in an attempt to cross the Atlantic, in 1975, as part of a performance project called In Search of the Miraculous. In the first part of the project, however, Ader took a nighttime walk from the Hollywood Hills to the Pacific, a journey Horvitz’s map echoes.

Flyer for a book signing for Rarely Seen Bas Jan Ader Film, by David Horvitz, 2009.

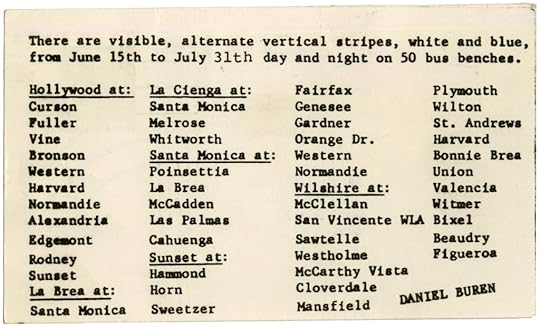

The announcement card for Daniel Buren's Bus Benches, in Los Angeles, 1970.

In the early seventies, Daniel Buren distributed his signature blue-and-white, vertically striped paintings around various cities. A cache of cards from this period advertising the installations tells you what to look for and when and where, but not in the way you might expect. The card for his bus benches project from 1982, for instance (the project was initiated in the seventies), lists the locations of fifty bus benches around Los Angeles at which the stripes could be found, “day and night.” Another such project lists a billboard’s location as 11501 West Pico, in Los Angeles, “across the street from the Chung King restaurant.” It doesn’t get any more in situ than that. But the best may be a card from 1970 that provides the details, such as they are, for an installation in New York: the dimensions are “variable according to the day”; the color is “arbitrary according to the day”; and the location is “different every day.” The card offers a phone number that can be called at any hour for more information. But a note at the top of the card is significant: “You are invited to read this as a guide to what can be seen.” Art isn’t always what—or where—you expect to find it.

Nicole Rudick is the managing editor of The Paris Review.

Take My Breath Away, and Other News

A still from Top Gun, 1986.

Rivka Galchen on Kafka (or rather, his biography): “It has been said of Kafka’s work many times that the thing to remember is that it is funny. Kafka was known to laugh uncontrollably when reading his work aloud to friends, and though that sounds more like anxiety than hilarity to me, the funny point endures. But what kind of funny is he? … One element of the comedy of Kafka’s biography is the way his life, at whatever moment, is dwarfed by his work.”

In the eighties, Hollywood’s big-budget movies were teeming with sex scenes: The sex was often in silhouette, yes, and usually accompanied by a saxophone, true, but it was there, just as it is in the human experience. “In the era of Top Gun, The Big Easy, Body Heat, or other steamy Hollywood thrillers, the goal was to appeal to both men and women with the promise of (among other things) onscreen sex. (Ergo the fabled ‘date night’ movie.) Now the goal is to appeal to adults and their twelve-year-old kids with the promise of the absence of sex.”

Kenneth Snelson’s Needle Tower, a sixty-foot sculpture at the Hirshhorn, comprises thin steel wires and barely touches the ground. How does it stay upright in strong wind?

“A couple of years ago, a Chicago-based corporate-identity consultant, Chris Herron, gave himself the ultimate challenge: rebrand hell. It was half gag, half self-promotion, but Herron took the project seriously, considering what it would take for a place like hell to become a premier destination in the travel market. Herron decided that what hell needed was a complete brand overhaul. The new hell would feature no demons or devils, no tridents or lakes of fire. The brand name was rendered in a lower-case, bubbly blue font designed to evoke ‘instant accessibility and comfort’. The slogan, which was once ‘Abandon Hope All Ye Who Enter Here,’ would be ‘Simply Heavenly.’ ”

Every December, the New York Public Library’s literary lions, Patience and Fortitude, have wreaths hung from their necks—and every year something seems to go wrong, somehow. (Last year the wreaths were simply too big.)

December 1, 2014

The Poetaster

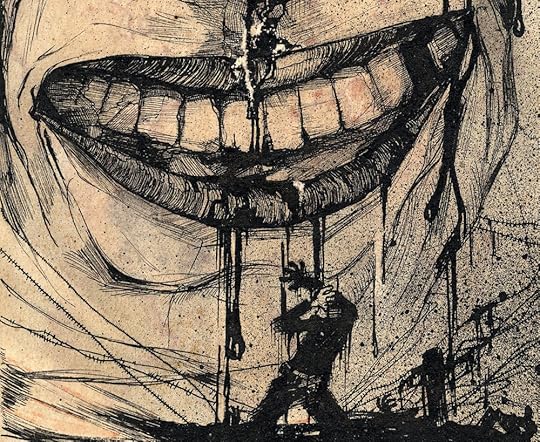

Detail from Kārlis Padegs’s Red Laughter, 1931

In 1876, Julia A. Moore published The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public, a best-selling series of poems to honor our nation’s centennial. Moore was an obituary poet: the elegy was her preferred mode. Local death notices and tales of wartime derring-do moved her to versify. She was especially fond of addressing poems to dead children.

Her work is, in a word, bad.

In fact, her collection sallied forth with such cloying sincerity—a note from the publisher claimed that any profits would be used “to complete the Washington monument”—that the satirists of the time decided to have a field day with it. Mark Twain parodied her in Huckleberry Finn; Bill Nye—the nineteenth-century humorist, not the contemporary scientist—said that hers was a poetic license that ought to have been revoked; The Hartford Times noted her collection’s “steady and unremitting demands on the lachrymal ducts”; and a critic in The Rochester Democrat wrote of her work, “Shakespeare, could he read it, would be glad that he was dead … If Julia A. Moore would kindly deign to shed some of her poetry on our humble grave, we should be but too glad to go out and shoot ourselves tomorrow.”

Best of all, maybe, was the review in the The Worcester Daily Press: “[Moore] reaches for the sympathy of humanity as a Rhode Islander reaches for a quahaug, clutches the tendrils of the soul as a garden rake clutches a hop vine, and hauls the reader into a closer sympathy than that which exists between a man and his undershirt.”

And so Moore gathered renown, like William McGonagall, as a poetaster, i.e., an inferior poet. (The word has fallen into disuse lately, but maybe it can have a renaissance in 2015.) You may chide her critics for their ironic jeering—it took some time, apparently, for Moore to get the joke, and eventually she was cowed into silence. By 1878 she’d been mocked from coast to coast and lampooned at her own public appearances. “Literary is a work very difficult to do,” she said to those who teased her.

But before you cluck, have a look at Moore’s poetry, which may make you want to throw tomatoes at her.

Here’s the whole of “Grand Rapids Cricket Club”:

In Grand Rapids is a handsome club,

Of men that cricket play,

As fine a set of skillful men

That can their skill display.

They are the champions of the West,

They think they are quite fine,

They've won a hundred honors well;

It is their most cunning design.

Brave Kelso, he's considered great,

Chief of the club he is found;

Great crowds he draws to see him bowl

The ball upon the ground.

And Mr. Follet is very brave,

A lighter player than the rest,

He got struck severe at the fair ground

For which he took a rest.

When Mr. Dennis does well play,

His courage is full great,

And accidents to him occur,

But not much, though, of late.

This ball play is a dangerous game,

Brave knights to play it though;

Those boys would be the nation's pride,

If they to war would go.

From Milwaukee their club did come,

With thoughts of skill at play,

But beat they was, and then went home—

Had nothing more to say.

Grand Rapids club that cricket play,

Will soon be known afar,

Much prouder do the members stand,

Like many a noble star.

Has there ever been a couplet as perfectly unpoetic as “And accidents to him occur, / But not much, though, of late”?

And lest you think maybe she was just having an off day, here’s some of “Roll on Time, Roll on.” (Note the absence of that direct-address comma—this may actually be a poem about punctual rollers.)

I was happy then as a girl could ever be,

And live on this earth here below—

I was happy as a lark and as busy as a bee,

For in fashion or in style I did not go.

My parents were poor and they could not dress me so,

For they had not got the money to spare,

And it may be better so, for I do not think fine clothes

Make a person any better than they are.

Some people are getting so they think a poor girl,

Though she be bright and intelligent and gay,

She must have nice clothes, or she is nothing in this world,

If she is not dressed in style every day.

Remember never to judge people by their clothes,

For our brave, noble Washington said,

“Honorable are rags, if a true heart they enclose,”

And I found it was the truth when I married.

You can read more of Moore here; and I’d be remiss if I forgot to include a link to Walter Blair’s impassioned, well-argued defense of Moore, written as an introduction to her collected works. “Mrs. Moore deserved a better fate,” he says. “Read without any thought of their historical setting, her songs endure the test of true literature by charming the reader. Considered against the background which made them possible, they present an interesting and vivid picture of a forgotten period in America's past.”

Hard and Fast

Don’t ask. (From the V Squared ad.)

If, by any chance, you read the print edition of the Sunday New York Times, as I did around two in the morning, perhaps you, too, were arrested by the full-page advertisement on A23. 11-YEAR-OLD, TWIN ROCKERS, VITTORIO AND VINCENZO OF V² SWEEP LOS ANGELES MUSIC AWARDS! blares the headline. There are seven accompanying photographs. “V² rocked the Avalon Theater, leaving no doubt that they owned the night and their 7 nomination categories,” reads one caption. “Standing ‘O’ for Vittorio and Vincenzo, 11-year-old superstars!” says another. The picture is of a bunch of grown-ups; one of them is sort of standing up.

The text is laid out like a news story:

Rock N Roll history was made by Santa Rosa, CA home grown rock sensations, Vittorio and Vincenzo of V² (pronounced V Squared). The boys, who only started playing music a few years ago at Rock Star University, Santa Rosa, became the youngest artists to ever perform at the Los Angeles Music Awards, thrilling the sold out crowd of Hollywood celebrities, music industry executives, and music fans lucky enough to secure a ticket to see these future Rock N Roll Hall of Famers perform. Vittorio and Vincenzo did not disappoint.

Who are these future rock-and-roll hall of famers? Who are their parents? What’s Rock Star University—and who had they beaten out for LA Music Award domination? Naturally, I switched on my phone to find out. After all, by this hour, I assumed, this weird vanity project would have at least put a dent in the Internet.

But the answer was silence. Okay, not total silence—the band has a Web site featuring videos. But that was pretty much it. (To hear their original composition “We Want to Rock You Hard and Fast,” you have to watch twenty-plus minutes of fog-heavy concert footage.) The “news” network, Rock News Around the Web—where the boys get interviewed by an anchor called Natalia Alexander—does not even have a dummy address.

To me, a full-page Sunday ad still felt impossibly momentous; if nothing else, it was expensive. And yet, like the provosts of Rock Star University, I had apparently taken my finger off the pulse. This feels like a new paradigm: we now live in a time when you can take out a full-page ad in the paper of record, heralding twin rock sensations, and not even rate a mention from Gawker.

Here is how one of the video promos starts: a trick driver races a classic car with the vanity plate V 2 ROCKS around some back streets. Two teenaged hotties in stripper cop costumes pull the car over; inside are Vittorio and Vincenzo, dressed in sort of mobster outfits. After refusing to provide a license and registration, they bribe the “cops” with a million-dollar bill, and give them VIP passes to their concert that night.

It looks like the kids may have had a strong hand in writing and directing their material; this is clearly what a ten-year-old would do with a budget. I’m just glad the kids still know the value of print.

Still Weird on Top

Barry Gifford’s novels find a new generation of readers.

From the poster for David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990), which was adapted from Gifford’s novel.

Barry Gifford’s novel Wild at Heart turns twenty-five this year. It tells the story of Sailor and Lula, two young lovers on the lam, driving their ’75 Bonneville convertible toward a better life but finding the violent reality of America instead. David Lynch saw something intoxicating in their pure, honest love. “I wanted to go on that trip,” he wrote. “It was like looking into the Garden of Eden before things went bad.” He asked Gifford to cowrite the screenplay. The film, starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and launched Gifford’s novel onto the best-seller list. Earlier this month, a sold-out audience crowded into a theater at the Anthology Film Archives to see an X-rated cut of Wild at Heart. (It was the European edition, which features some ten extra seconds of sex deemed too explicit for the U.S. audiences of 1990.) Before the screening, Gifford read from his next novel, The Up-Down, a continuation of the Sailor and Lula saga in which the couple’s son, Pace, embarks on a spiritual quest for the mysterious fifth direction, the “up-down.”

Gifford has lived a life in miles instead of years. He’s never in one place too long, but during moments of cultural upheaval, he has found himself, with an almost Forrest Gump–like serendipity, in the right place at the right time. An autodidact, he’s published poetry, fiction, memoirs, biographies, plays, and screenplays. He turned sixty-eight this year; The Up-Down will be his twentieth novel and his fifty-seventh book. Next year, a new play of his will premiere in New York and a film he wrote will begin shooting in Brazil, with Willem Dafoe as the lead.

At Sarabeth’s in Tribeca, I sat down with Gifford for breakfast the morning after the screening. He joked about the youthful audience, many of whom were younger than the book. “Millennials are discovering Wild at Heart for the first time,” he said. “I’m not quite sure they knew what they were in for.” The Up-Down is, Gifford claimed, the final chapter in the Sailor and Lula story, a story Gifford has told over the course of a quarter century. The collected Sailor and Lula saga runs nearly eight hundred pages and comprises Gifford’s magnum opus, full of recurring characters and settings that center around the titular couple.

Throughout the seventies and eighties, Gifford had been working as a journalist and traveled the world reporting stories. He was under contract to write a book about deep-sea fishing and was staying in a Cape Fear hotel in North Carolina when he heard the voices of Sailor and Lula talking. He called his agent and told him to return the money for the fishing book, because he was onto something. He wanted to write a novel. “My agent almost had a heart attack,” Gifford said. The Twin Peaks producer Monty Montgomery—perhaps better known as the Cowboy from Mulholland Drive—gave Lynch an early copy of the novel. Lynch optioned it, and a year later, they premiered the movie at Cannes.

Decades later, Sailor and Lula’s prelapsarian passion in Wild at Heart resonates with new readers because Gifford doesn’t bullshit; he doesn’t shy away from the hysteria of young romance. Or its growing darkness, for that matter. The novel is a “violent satire,” he told Chicagoist in 2010: “What I wanted Sailor and Lula to represent were innocents. That they were perhaps naive, but innocents nevertheless. And here was all this shit raining down around them … It’s a picaresque. They’re just going down the road, just like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.” Early on, Lula delivers her famous line—“This whole world is wild at heart and weird on top”—as apt an observation now as it was twenty-five years ago.

Gifford was born in 1946, in a hotel room in Chicago, to a racketeer father and a beauty-queen mother. They lived at times in hotels in South Florida, New Orleans, and Havana. Because they moved around so much, Gifford didn’t get much formal education. He learned from late-night noir movies and the strange characters that passed through the hotel lobbies. His father died young, and he and his mother both had to find work. Later, he went to the University of Missouri on an athletic scholarship, but he promptly dropped out and went to Europe to try his hand as a musician and poet. Gifford traveled around for the next few years and then settled in London, amidst the psychedelic movement. It was 1965 and he was twenty-one.

“I have a lot of stories from that time that many people find hard to believe,” he said. He was friendly with Eric Clapton and the Kinks, even met Jimi Hendrix and John Lennon a few times. “I tell these stories not to drop names but to say that the scene was small back then,” he said. “It wasn’t a big deal.”

In 1967, he went to San Francisco during the Summer of Love and was an original writer for Rolling Stone. He fell in with the Beat writers that were still around, including Allen Ginsberg, with whom he became close. They shared a love of Williams Carlos Williams, whose poem “To Elsie” Gifford often cites when describing Sailor and Lula: “The pure products of America / go crazy.”

Over the course of the next few decades, he traveled, writing poetry and nonfiction and befriending outsider writers like Jim Harrison and Larry Brown. He published two novels, but they didn’t sell. Then came Wild at Heart, and his career took off. Ever since, he’s lived in Europe, New Orleans, and New York, but keeps a home base in San Francisco, making a living from his work. When I asked him how he managed to go from an eighteen-year-old kid with a rucksack and thirty dollars in his pocket to a full-time writer, he told me an anecdote about Timothy Leary. (Another old friend, of course.) “Someone asked Tim what he did for money and he said, I just dip my hand into the stream.” And he offered a word of advice: “Be generous and don’t talk down to people.”

A few days after the Wild at Heart event, there was a screening of Lost Highway, Gifford’s other film collaboration with Lynch, at the Museum of the Moving Image. The audience was again packed with young people. I looked for Gifford after the screening, hoping to ask him why the texture and tone of Lost Highway depart so radically from Wild at Heart—but he was nowhere to be found. I asked someone if they’d seen him. “He left already,” she said. “He’s on the road first thing tomorrow.”

Michael Bible has written for the Oxford American, Al Jazeera America, Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Tyrant, and ESPN: The Magazine, among others. He’s currently the senior staff writer at Nerve.com. His novel Sophia will appear in 2015. He lives in New York City.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers