The Paris Review's Blog, page 640

November 26, 2014

Alec Soth’s Niagara, Annotated

“Why do the falls simultaneously attract lovers and suicidals?” (Click to enlarge.)

As we mentioned on Monday, next week PEN American Center presents “First Editions, Second Thoughts,” an auction of seventy-five annotated first editions at Christie’s New York, including work by Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, and Jane Smiley, among others. The proceeds will benefit PEN, a writers’ association dedicated to protecting free expression.

PEN shared with us a few of the annotated pages from the photographer Alec Soth’s second monograph, Niagara (2006), which features pictures of the falls and the people who visit them: newlyweds and lovers in a milieu of motels, parking lots, and pawnshops, the unlikely venues for human desire. The prolific Soth has appeared on the Daily in many forms over the years; there are few photographers whose work is so consistently compelling, so intimate. (Art in America : “Perhaps more than any other contemporary photographer, Soth understands the tension between art and document inherent in the photographic medium. Situating his work between these two tendencies, he has created surprisingly personal metaphors for the collective hopes and anxieties governing post-9/11 America.”)

The annotated edition of Niagara finds Soth captioning his photos with canny asides, some contemplative and some rueful. (“I should’ve photographed her alone,” he writes below a picture of a newlywed couple at a motel.) He’s also supplied—and glued onto the book’s blank pages—several unseen photos from the same sessions, usually with notes as to why they were left out of the monograph; it adds up to an engaging look at his composition and selection process. Here are a few more photos of the edition:

“Chantelle had a giant portrait of herself over her bed.”

“My primary interest when photographing couples is to see how they hold each other.”

“Rainy wedding day. I should’ve photographed her alone.“

“A Mosaic of Filth,” and Other News

Steven Hirsch, Rhode, 2014, color photograph. Image via Lilac Gallery

A new copy of Shakespeare’s first folio—only the 231st known to exist—has been discovered in France. “It probably crossed the English Channel in the hands of English refugees fleeing from Anglican persecution in France.”

The unlikely rise of the thrift store: the Goodwills and Salvation Armies of the world were not always looked upon so kindly in America. In “The Blue Silk,” an 1884 short story in the Saturday Evening Post, “the protagonist, Louisa, buys a pre-owned dress from the ‘Jewess behind the counter’ of a resale store. When she wears it to a party, not only is she is socially ostracized for wearing the old dress of another girl, but she comes down with smallpox because of contamination from the resale store.”

The photographer Steven Hirsch has a new series on the Gowanus Canal, a Superfund site in Brooklyn: “The images are solely concerned with the surface of the water—the gonorrhea, coli, and putida bacteria that cling to one another there in a mosaic of filth. These microorganisms and pathogens create a kind of membrane on the surface of the canal, ‘like an acetate,’ says Hirsch. In the illusions of light and liquid they look like a solid substance, but when, out of curiosity, Hirsch tried to scoop them up they immediately dissolved.”

“An entire cottage industry of malfeasance and predation has erected itself” around academic research journals, including a popular pay-to-play scam that asks scholars to pony up for inclusion in such bogus publications as the International Journal of Advanced Computer Technology. Recently, a researcher sent that “journal” an abstract; it just said “Get me off your fucking mailing list” over and over again. “To his mild surprise, not only was this groundbreaking study accepted—with fraudulent peer reviews and everything!—it was put into layout, and a PDF was generated for his ‘perusal,’ along with, of course, a humble request for $150, to be submitted by wire transfer, as all legitimate scholarly transactions are.”

The writer Jörg Fauser was an essential part of the German counterculture, but English-language readers know almost nothing about him. A new translation of his novel Raw Material is coming: “To foist a genre on it, it’s a picaresque, but what a crazed, leaping, unmoored and hilarious voyage it is.” I particularly like its take on booze: “Drink is an immersive, highly social drug that can often lead to new friendships and interesting sexual adventures. It also leads to weight gain and bloat, which is not a good look for a revolutionary.”

November 25, 2014

Limbo

John Singer Sargent, Violet Paget (Vernon Lee), 1881

Vernon Lee—the pen name of the English writer Violet Paget—was a travel writer, novelist, musician, and critic with a strong interest in aesthetics. One of the first to bring the concept of Einfühlung, or empathy, into English criticism, she was also an outspoken follower of Walter Pater’s aestheticism. “An engaged feminist, she always dressed à la garçonne,” someone has written, amazingly, on Wikipedia.

Lee’s work is included in any collection of Victorian ghost stories. Her work is haunting in the true sense, and not merely because it deals so frequently with possession. Her stories are graceful, engaging, surprisingly strange. There are often lesbian subtexts; the supernatural was a vehicle for a writer like Lee to indirectly explore such themes.

I first came to Lee through a novella called “A Phantom Lover” in a collection from the 1960s. As with many of Lee’s works, the narrator is male. This one also features a woman given to cross-dressing, specifically period Elizabethan cross-dressing. A nameless painter is invited to an isolated, beautifully preserved country house to do portraits of the young squire and his wife. The latter proves to be a mysterious and somewhat perverse creature, remote and self-absorbed, utterly obsessed with the story of a long-dead ancestor. The love triangle that arises is not what one might expect: it’s far creepier. Find it if you can, and then if you’re anything like me, you’ll want to seek out the 1890s collection Hauntings.

The essays age less well, unless you have a particular taste for Victorian rhetoric. But one of my favorite Lee quotes comes not from her fiction but from the 1897 essay “Limbo”:

Let us rather think gently of things, sad, but sad without ignominy, of friendships stillborn or untimely cut off, hurried by death into a place like that which holds the souls of the unchristened babies; often, like them, let us hope, removed to a sphere where such things grow finer and more fruitful, the sphere of the love of those we have not loved enough in life.

But that at best is but a place of ghosts; so let us never forget, dear friends, how close all round lies Limbo, the Kingdom of Might-have-been.

The Windows on the World Finalists

Earlier this month, we announced our Windows on the World contest, giving readers the chance to have the views from their windows sketched by Matteo Pericoli. We’re happy to share the views from our five finalists—their photographs and essays are below. We’ll announce the winner on Friday.

Zara Khadeeja Majoka, Lahore, Pakistan

Zara Khadeeja Majoka

My window looks out at the ugly, unpainted, pipe-decorated grey concrete side of the neighbors’ house. Parsimony has preached to many in Lahore that having only the front of your house painted is enough; if your neighbor’s soul shrinks at the sight of the frowning, naked grey concrete, well then they must deal with it. And so, of course, that is what I must do. Joohi is a flowering vine that produces small, fragrant pink and white flowers as lovely and delicate as its name. I had some of the tiled floor beneath my window removed to reveal the soil and planted joohi; within three months, laden with flowers, it had made its way up to my second-floor window. Some days the liveliness of joohi would seem absurdly lovely in contrast with the concrete peeking in from behind its spread. On other days, the unavoidable sight of the concrete still menaced. I am aggressively ugly, it said, and I will outlast your fragile, pretty vine. I needed a tree, I decided, and opted for a peepul, a tenacious tree that clings to whatever scarce particles of soil it finds, and is often found sprouting out uncannily from walls and roofs and pipes. I had some more of the floor cleared and planted a sapling. My parents warned that in sixty or so years its unfurling roots could destroy the foundations of both our house and the neighbor’s. I pointed out that we were all likely to under-live this problem, so they agreed. I think it will be a year before my peepul reaches my window with its beautiful heart-shaped leaves, the tips of which extend like sweet, elongated musical notes. A peepul tree grows and grows and lives for hundreds of years. Four thousand year old clay seals from the Indus Valley Civilization depict deities standing inside the sacred peepul, Vishnu is said to have been born under a peepul and Gautama Buddha is said to have attained nirvana while meditating beneath one. I only wish to watch mine grow, and know that it will outlast the concrete.

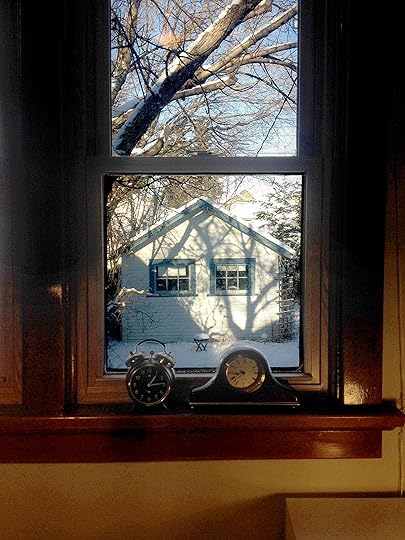

Roderick Moody-Corbett, Calgary, Alberta

Roderick Moody-Corbett

A pair of broken clocks, stilled at odd hours (impossible to say who gave first), rest on the window’s scabbed wooden sill. A garage, the key to which I seem to have lost, if I ever owned (I am house-sitting for friends on sabbatical in Germany), overwhelms my attention, invariably. In the summer, neighborhood cats laze on its mossy slopes. Today, the snow-capped roof is empty. My own cat, nose pressed to the window (she remains one paw too pudgy for the sill), regards this vacancy with an amount of nostalgia, amusement and regret.

Shadows twitch on the clapboards; magpies tinsel the eaves. Funny, I often forget about the short blue stool sitting below the windows whose shades are unevenly drawn.

Fixed to the garage is a slant metal trellis with small lantern feeders sprigged to its rails. The feeders appear empty. If I knew where they kept the birdseed (probably in the garage), I might fill them.

Heidi Lang, Innsbruck, Austria

Heidi Lang

From my window, I see a building with scant, round windows, like portholes on a cruise ship. Hulking over the ship are the Alps. After having spent so many years on the Great Plains, in a sprawling river city with few dominant shapes, seeing the mountains every morning still surprises me.

My corner apartment is cramped, but from my wraparound balcony I can see in every direction. I can see the school across the street, which keeps its fluorescent lights on even after the neighborhood Lokal has stopped serving Zipfer. I can see hiking trails, but not their avalanche warning signs. I can see a moped shop, but more often I hear it. Hemmed in by the mountains, the city is small enough and the streets congested enough that the fastest way to get around is by bicycle. I walk.

My balcony keeps quiet company with the balconies of neighbors. There’s the elderly gardener, who lives with his wife in the stern of the retired ship. One afternoon he snipped grapes, bunch by bunch, from the single row of vines in his garden, collecting the harvest in a five-gallon bucket. There’s the woman who grew up in the guesthouse that once stood where my apartment does now. She lives with her middle-aged daughter, who shouts cheerfully to me from her balcony.

On a rare sweltering day, the neighbors and I spent the afternoon on our balconies in various stages of unapologetic undress, dutifully not noticing each other. The hot wind billowed in the bed sheets I’d hung up to dry. I sat in a deck chair. The woman who grew up where I live now sat on her terrace, her eyes closed and her short hair gathered up in what looked like a swimming cap.

Simon Rowe, Himeji City, Japan

Simon Rowe

Time has gathered Japan’s villages into towns and cities, even turned some into metropolises, but the cho, or neighborhood, remains the heart and soul of the nation.

Mine resembles an overcrowded circuit board with its dense clusters of houses spanning a century in design and its winding pathways which deliver children to school, businessmen to bus stops and elderly to their kitchen gardens. This is Kamiono-cho, in Himeji city—where the westward sprawl that begins in Osaka finally runs out of steam.

Bamboo grows as thick as a man’s leg in the forests beyond the neighborhood, lofty and mesmerizing when the valley winds blow. In Autumn, the smell of burning rice chaff reaches through the window, signaling the end of the harvest season and the start of the festivals which celebrate its bounty. Taiko drum volleys rattle my window, just as the earthquakes do.

Snow dusts the rooftops in winter. Through the opened window, knife-edged winds carry a whiff of Siberia—chilling, yet invigorating. Spring sees cherry blossoms garnish the neighborhood and family picnics mushroom beneath them. Then the blossoms fall, like the brief and beautiful life of a samurai, with the first spring rains. Summer arrives and the window is shut to the whining insects and the suffocating humidity which descend on the city. The pane rattles once more with the typhoons of late summer; TV antennas waggle on tiled roofs, momentarily lost to the rain.

The old neighborhood, once famous for strawberry growers, is vanishing. Where fruit grew, model homes now stand. Outside them, housewives gather on dusk to chew over the day’s proceedings and await their children’s return from school. Long after dark, the buses will disgorge their tired husbands, who will drift heavy-hearted back to their homes and sleeping families.

Jessica Thummel, Denver, Colorado

Jessica Thummel

The man who previously lived in my apartment had lived here since the early 1980s. He was a hoarder and apparently died alone in my bedroom and wasn't found for weeks. I often think about him and how this view must have changed over the course of those thirty-years. All around, buildings and houses and businesses have come and gone, and yet the distant horizon has stayed the same. It's comforting to think of the writing life in this way. To see those mountains, far off in the distance, and know that they will always be there, ready to be climbed, no matter how many new obstacles or roads intersect in the foreground.

The Ballad of Ferguson, Missouri

A man unzipping his fly is vulnerable to attack.

Then the zipper got stuck.

An angel flies in the window to unstick it.

A drone was monitoring all this

In real time

And it appears on a monitor on Mars,

Though of course with a relay delay.

One of the monitors at the Mars base drone station

Is carefully considering all your moves for terror output.

But not to worry. Forget about about about it.

The body of the man you were

Has disappeared inside the one you wear.

Reminds me of the story of the man who had nipples

Where his elbows should be and whose skeleton

Was on the outside of his body.

The guy walks into a shop on Madison to buy some clothes

And buys some and walks out wearing them

Wearing them and into the Carlyle bar.

One of the waiters, originally from Algeria of all places,

Recognizes him and says with the strong accent

He has despite many years of living in the United States:

Your usual?

A man has disappeared inside his corpse.

His corpse has disappeared inside a cause.

Reminds me of the video of Robert Kennedy

Announcing to a largely black audience at an outdoor campaign rally

At night in Indianapolis

That Martin Luther King had been shot

And killed and by a white man.

Martin Luther King is dead.

Skin color is the name.

Skin color is the game.

Skin color is to blame for Ferguson, Missouri.

The body of the man you were

Has disappeared inside the one you wear.

I wouldn’t want to be a black man in St. Louis County.

A man unzipping his fly is vulnerable to attack.

Then the zipper got stuck.

An angel flies in the window to unstick it.

Here comes light-skinned Billie Holiday, Lady Day, no angel!

A drone was monitoring all this,

Which appears on a monitor on Mars,

Though of course with a relay delay.

One of the monitors at the Mars base drone station

Is carefully considering all your moves for terror output.

But not to worry.

Fuhgeddaboudit.

Reminds me of the story of the man whose smile

Shot out flames and whose skin

Was on the outside of his body.

The guy walks naked into a shop on Madison Avenue to buy some clothes

And buys some and walks out on fire wearing them and goes straight

Across the street in flames to the Carlyle bar.

One of the waiters looks as if he’s having a stroke

And raises his hands in Arabic,

Palms in, and murmurs a prayer,

And brings God a glass of humble water.

You can change

From chasing Communists

And chasing Jimmy Hoffa, the mobster union president

Who however supported civil rights,

And change to blessing and being blessed.

Some victims change from a corpse to a cause.

You can change

Reminds me of the video of Robert Kennedy

Announcing to a largely black audience at an outdoor campaign rally

At night in Indianapolis

That Martin Luther King had been shot

And killed and by a white man.

Martin Luther King is dead.

Frederick Seidel received the 2014 Hadada Prize. This poem will appear in our Winter Issue, available next month.

The In-Between Space: An Interview with Shelly Oria

Photo: T. Kira Madden

The eighteen stories in New York 1 Tel Aviv 0, Shelly Oria’s debut collection, are beguiling, bizarre, and wise. (One of them, “My Wife, in Converse,” appeared in The Paris Review earlier this year.) Her sentences, with their clear-eyed, authoritative calm, underscore and complicate the unlikely circumstances in which her characters find themselves, and the chaos of their inner lives. Here, for example, is the narrator of “This Way I Don’t Have to Be,” on her addiction to sleeping with married men:

I always look them in the eye throughout, and that can be tricky, because they mostly try to avoid the intimacy of eye contact. I wait, and then suddenly it’s there, passing through them like a wave. In that moment, their entire lives turn to air … For one brief moment, they go back in time, they make different choices, they are different men. And my body is the time-travel machine that takes them there.

Born in Los Angeles but raised in Israel, Oria moved to the United States at twenty-five, five years after finishing her compulsory military service. Though she was fluent in English, she thought—and wrote—in Hebrew; hoping to attend the writing program at Sarah Lawrence College, she taught herself to write fiction in English, an experience she describes as “one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.” Her prose is both energized and measured, and perhaps this is the effect of customary Israeli volubility short-leashed by an inner translator—a tiny version of the author herself who sits at her little desk inside the brain, reading the rough transcripts as they are faxed up from the heart, and forever sending notes back down that read, Yes, but is that really exactly what you meant to say? All authors live with a version of this little demon; it just happens that Oria’s is bilingual and combat trained.

I should mention that Oria is my colleague at the Pratt Institute. She is also a life/creativity coach and hosts a reading series in the East Village. Between all of that and a book tour, she is very busy, for which reason, though we would have much preferred the pleasure of each other’s company, this interview was conducted via e-mail.

I find myself returning to the scene in the title story where Pie—who is in a three-way relationship with a woman and a man—divides herself into “Me No. 1” and “Me No. 2.” No. 1, “the Israeli who was taught that being tough and being strong are the same thing,” is ready to walk out the door on both lovers immediately. No. 2, “a woman who successfully impersonates an American” and “has a lot to prove,” wants to stay. Pie seems to think that No. 1 has the right take on the situation, but it’s No. 2’s position she adopts as her own, and I for one am hardly convinced that she’s wrong. Might you speak, then, to the risks and allures of pulling off a successful impersonation?

The thing is—and maybe this is obvious—both Pies are wrong. By which I, of course, also mean that they’re both right. And to me that’s what the story is trying to do, and what the book is trying to do, and what I’m trying to do, not only as a writer but as a human—challenge this idea of either-or, hang out a bit in the in-between space. Or really, the both space. As far as I’m concerned, that goes for nationality, for sexuality, for identity in general. We’re hardwired toward this dichotomous way of thinking about and constructing identity. It’s almost an addiction—a cultural addiction to categories.

One finds it even in those places, namely the arts, where one might have hoped to be excused from such rigidity.

Doing interviews and readings, I’ve noticed a prevalent idea in the book, of lies repeating themselves to the point of becoming truths. Big shifts in identity function that way —you lie to yourself in some small or medium-sized way until you start buying it. A successful impersonation is not only successful in that it fools the person you’re interacting with. A truly successful impersonation is the kind where the impersonator starts believing her own lie. In that moment, that lie has become, at least to some extent, true.

I don’t think this is a bad thing at all. I mean, of course it could be—it depends on how far reality is from fantasy, I suppose. But the point I was making is that the experience of an impersonation becoming more and more successful over time is the experience of integrating a new identity.

So it makes sense that in the very next scene in the story, as the three of them are making love, Pie asks herself, “Who is this person? That me who isn’t Israeli and isn’t American, isn’t gay and isn’t straight—who is she?” Pie has found—or at least found a language with which to seek—identity from the very fact of her in-betweenness.

So it makes sense that in the very next scene in the story, as the three of them are making love, Pie asks herself, “Who is this person? That me who isn’t Israeli and isn’t American, isn’t gay and isn’t straight—who is she?” Pie has found—or at least found a language with which to seek—identity from the very fact of her in-betweenness.

In a way, the moment you’re referencing is a product of that “category addiction,” the culturally cultivated idea that our identity should fit neatly in a box. Which is predominantly a Western and male and white idea—by which I mean, it’s a privileged idea. That moment for Pie is a moment of inhabiting the “both” space, of saying, Oh, wait a minute, I am all these things at once. It’s her inability, or refusal, to choose or fit into one box that defines her.

You also work professionally as a life/creativity coach. Do you think your coaching work makes you more comfortable with these kinds of big questions about who we are and what we want?

Well, the kind of conversations I’m having when I coach are inherently open and flexible, sort of stretching themselves in different ways to meet the client where he or she is, and so in that sense, yes, sometimes. But mostly those conversations tend to be very specific. A person is less likely to say, You know, I’ve been wondering about the relationship between truth and lie, and more likely to say, Last night at the gala I felt like a fraud. And coaching is not about giving advice, really. It assumes the person has all the answers, but that these answers aren’t always or aren’t fully accessible. Much of the work, therefore, is in asking the right questions.

In a few of these stories, like “Victor, Changed Man” or “The Beginning of a Plan,” reality itself is dynamic and mutable—what a category addict might resort to calling magic realism—but I was reminded most strongly of the fictions of Gary Lutz, which was surprising, since at the sentence level your styles are radically different.

I discovered Gary Lutz in grad school, when I was very new to writing in English, which is my second language. I think one of the biggest gifts of reading him has been learning both to credit the reader and to trust language much more. A Gary Lutz story assumes an intelligent—arguably brilliant—and fully engaged reader. And, of course, a Gary Lutz story trusts that language in and of itself can create suspense and hold emotional weight and punch a reader in the gut—all the things we traditionally attribute to plot. So if you’re a writer who thinks about language a lot, reading Gary Lutz changes you. But I think all the writers who inspired me during that formative time in my writing life will forever be more than just influences. Their voices had a huge, long lasting effect on me. Grace Paley is another such hero. Judy Budnitz, Joy Williams, George Saunders, Aimee Bender, Amy Hempel.

So many of your characters seem to want, more than anything else, to have their reality confirmed by a lover’s attention. There’s a lot of ego in that desire, but a lot of supplication, too. You’re giving someone else enormous power over you, and that person might not know what to do with it or even want it at all. Are people too quick to give away this kind of power? Is love just a form of attention?

I do think love is a form of attention, yes. It’s arguably much more, too, of course, and I think it has the power to confirm and confer not only our reality but our humanity. But at its core it’s a deep form of attention—we fall in love with the people who pay attention the right way, to whatever it is in us that most needs attention, and who let us do the same for them, no?

But then, yes, some of the people in my stories get in trouble for it. I think you’re right to use the word power, because that’s what really gets them in trouble—not wanting or needing the lover’s attention, but rather giving themselves up to it in some profound way. This can happen at any age, but I do think it’s emotionally young, the feeling that I will cease to exist if this person stops loving me. Ideally, over the years and through experience and awareness, we learn that no one really has that kind of power over us, and that when we feel as though someone does it’s actually our psyche asking for our own attention, et cetera, et cetera. But in fiction, these are the characters we want, right? Young hearts make the best mistakes on the page.

Justin Taylor’s new book, Flings , is available now.

When Art Got Expensive, and Other News

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Juan de Pareja (detail), 1650.

Finally available, after forty-one years: Gravity’s Rainbow , the audiobook. It comprises thirty CDs and is performed by a superhumanly patient soul named George Guidall. “How on earth, I wondered as I stripped the wrapper, is poor Mr. Guidall going to render the sudden outbreaks of crazed capitals, or librettos in which stoners with guitars pastiche Rossini, the instructions helpfully stating ‘(bubububoo[oo] oo [sung to opening of Beethoven 5th, with full band])’? He turns out to do it in a slow and deep-voiced manner, beneath whose calm avuncularity you can detect anxiety, even mania, bubbling but never quite erupting.”

New York has fewer used bookstores than ever before, and yet the Strand continues to thrive. How? It’s certainly cheerier than it used to be, which doesn’t hurt—before it was renovated in 2003, it was pretty bleak. “Like a lot of businesses that had hung on through the FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD years, it looked broken-down and patched-up. The bathroom was even dirtier than the one in the Astor Place subway. You got the feeling that a lot of books had been on the shelves for years. The ceiling was dark with the exhalations from a million Chesterfields. There were mice. People arriving with review copies to sell received an escort to the basement after a guard’s bellow: ‘Books to go down!’ ”

Meghan Daum on suffering: “ ‘The culture is obsessed with the idea that if you go through a crisis, you’re going to come out of it a better person,’ Daum says, explaining her frustration with ‘the pressure we put on people ... to have epiphanies where suddenly it all makes sense.’ This ‘redemption pressure’ is sentimentality’s aggressive shadow, a way of forcing people in terrible situations to make us feel better about what they’ve been through. But as she demonstrates in her essays, ‘sometimes you don’t learn anything. It is what it is, and there is no closure.’ ”

On November 27, 1970, Velázquez’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja became the first painting to sell for more than a million pounds. “It was finally knocked down for a staggering £2,310,000, almost tripling the previous world auction record for a painting. Even the most hardened dealers sitting in the audience breathed gasps of disbelief. Then there was a spontaneous burst of applause. The auctioneer left his rostrum, the painting was hastily removed, and sheer pandemonium broke out.”

A new service, Deathswitch, allows you to communicate from beyond the grave: “Subscribers are prompted periodically via email to make sure they’re still alive. When they fail to respond, Deathswitch starts firing off their predrafted notes to loved ones. The company now has thousands of users and effectively runs itself. Among the perks of a premium Deathswitch account is the ability to schedule emails for delivery far in the future: to wish your wife a happy fiftieth wedding anniversary, for example, thirty years after you left her a widow.”

November 24, 2014

All the President’s Turkeys

Horace Vose with a turkey for President McKinley. Vose secured presidential turkeys for more than thirty-five years.

From Turkeys, all varieties: Their care and management. Mating, rearing, exhibiting and judging turkeys; explanation of score-card judging, with complete instructions , published jointly by the Reliable Poultry Journal Publishing Company and the American Poultry Publishing Company in 1909.

A turkey boiled

Is a turkey spoiled,

A turkey roast

Is a nation’s boast,

But for turkey braized

The Lord be praised.

The most famous grower of turkeys in the United States is Horace Vose, of Westerly, Rhode Island. Mr. Vose last year followed his annual custom of sending a Thanksgiving turkey to the President of the United States, a custom which he began in Gen. Grant’s first term. He has autographed letters of thanks from all the presidents since then. Mr. Vose goes to a great deal of trouble to get the President’s Thanksgiving dinner. Besides growing turkeys he deals in them, and after the chicks have been hatched a month or two he makes a tour of the farms for miles around. If he sees a particularly fine chick be secures an option on it, and directs that it be given special care. He makes other visits later in the season and bids for every fine turkey that he sees. When Thanksgiving approaches the Rhode Islander has control of practically all the finest birds for miles around. He is the largest shipper of turkeys for the New York market. This is Mr. Vose’s philosophy:

“The object of fattening a turkey is to produce firm, finely flavored, luscious flesh. Therefore it should be fattened on whole corn—not meal—as the corn gives a firmer consistency to the flesh. It should never be stuffed artificially or confined in close quarters. If sweet apples are available they may be fed, as nothing will give a nicer flavor to the flesh.”

[…] The London Board of Agriculture reports great success in fattening turkeys with a cramming machine. A mash of equal parts of ground barley, corn and oats, with a small amount of melted fat and linseed meal was used, enough skim milk being added to make it the consistency of cream. At first there was difficulty in feeding the turkeys, owing to their size and strength, but the operator finally overcame this by placing the fowls on a low stand so that their heads were on a level with the nozzle of the cramming machine. It is stated that “after a day or two the turkeys became accustomed to this manner of feeding, and when meal times came they showed much eagerness to mount the stand and receive their share of the food.”

Sleep of the Just

Illustration by Randolph Caldecott.

You know how J. M. W. Turner tried to exhibit his work at the Royal Academy and the Royal Academy was all, Wow, your work is way too innovative and interesting and we can’t show it because it would threaten all our hidebound, bourgeois ideas and force us to reevaluate everything and make important societal changes? Yeah, well, I totally see their point. Once a year, anyway.

Because every November, all the food magazines and blogs start trying to bully us into to reinventing the wheel. Don’t be a fogey! they scream. What, you’re still eating turkey? HAHAHA. Well, if you insist on being a “traditionalist,” stuff that turkey with linguica and kale! Baste it with ramen! Douse it in pomegranate molasses! (All this is said in a vaguely threatening, SportsCenter-style cadence.) This isn’t your mom’s green bean casserole! You’re not even seeing those losers, are you, with their stupid political views and opinions about your love life? Surely you’re having some awesome no-strings Friendsgiving celebrating the new family you’ve chosen! Right? RIGHT?! SRIRACHA. SRIRACHA. SRIRACHA.

Look. I get the market demands of the newsstand. You can’t just recycle the same stuff year after year. Nor do I mean to advocate a slavish adherence to tradition. In my family’s case, that would mean cleaning the dining room table off in a panic at the last minute, barring entrance to the rooms where we’ve stuck all the mess, then watching my mother stand in front of the digital meat thermometer with tears rolling down her cheeks.

My own practices are less ambitious. I like order, I like guaranteed results, and I like perfection.

Is this lonely? Yes. Tyranny is lonely. But I cannot risk a guest—a Ruskin, if you will—succumbing to the lures of something “fun” and playing merry havoc with the priggish constraints of my menu. I was not always thus; life has made me harsh. Life and a particular batch of mashed potatoes made with Benecol butter substitute (because that’s what someone’s grandma had in the fridge), Bac-Os, and a garnish of coffee grounds.

In the upcoming Turner biopic, I have no doubt Mike Leigh will paint me and my kind as the villains. And this is how it should be: we are standing in the way of innovation. So be it. Let the others innovate and inspire. For every genius, there will be a thousand pie crusts made without a recipe, and the worse for it. While we beat on, boats against the current, lonely despots filled with butter.

Knowing My Place

The title page of Knowing My Place, annotated by Paul Muldoon. Click to enlarge.

On December 2, PEN American Center presents “First Editions, Second Thoughts,” an auction of seventy-five annotated first editions at Christie’s New York, including work by Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, and Jane Smiley, among others. The proceeds will benefit PEN, a writers’ association dedicated to protecting free expression.

Paul Muldoon’s first chapbook, Knowing My Place, is one of the books up for auction, and PEN has shared some of Muldoon’s annotations with us. Knowing My Place is so hard to come by that The Paris Review’s Art of Poetry interview with him makes no mention of it; his first full collection, 1973’s New Weather, is usually considered his first book. He does hint at the circumstances of Knowing My Place’s publication, though:

INTERVIEWER

While you were at Queen’s you joined a very famous writing group, and while still an undergraduate you published your first book, New Weather. How did all of this come about? Who had you been showing your work to?

MULDOON

Ciaran Carson. Frank Ormsby. There were people associated with a particular magazine, The Honest Ulsterman. I’d started publishing there when I was a teenager. When I went to Queen’s I was welcomed by Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley into a critical society called the Group, or the Belfast Group, which was the offshoot of the London Group. And our poems were critiqued there by Heaney, Longley, Stewart Parker, and various other luminaries lurking around. So I suppose the stakes were quite high.

One of the things about being eighteen or nineteen or twenty is that one’s daunted by nothing. So on some level I thought to myself, Well, you know, I can do this. That’s why people do almost everything, whatever it might be. Not only, I can do this, but, I can also do it better than this. I have a sense, which I try to give my own students, that it’s possible to write poems that are of a high quality.

Knowing My Place was published by Ulsterman Publications, which I can only assume is affiliated with the group mentioned here. It appeared when Muldoon was only nineteen, an undergraduate, in 1971; “the year decimalisation came in the UK,” his annotation to the title page says. (The pound sterling was subdivided in one hundred pennies where previously it had comprised 240 pence.)

Here are some more of the annotated pages in Knowing My Place:

On “Macha”: “This felt quite risqué at the time.”

On “Belfast“: “It didn’t make the cut when my first book came out.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers