The Paris Review's Blog, page 639

December 1, 2014

Still Weird on Top

Barry Gifford’s novels find a new generation of readers.

From the poster for David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990), which was adapted from Gifford’s novel.

Barry Gifford’s novel Wild at Heart turns twenty-five this year. It tells the story of Sailor and Lula, two young lovers on the lam, driving their ’75 Bonneville convertible toward a better life but finding the violent reality of America instead. David Lynch saw something intoxicating in their pure, honest love. “I wanted to go on that trip,” he wrote. “It was like looking into the Garden of Eden before things went bad.” He asked Gifford to cowrite the screenplay. The film, starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and launched Gifford’s novel onto the best-seller list. Earlier this month, a sold-out audience crowded into a theater at the Anthology Film Archives to see an X-rated cut of Wild at Heart. (It was the European edition, which features some ten extra seconds of sex deemed too explicit for the U.S. audiences of 1990.) Before the screening, Gifford read from his next novel, The Up-Down, a continuation of the Sailor and Lula saga in which the couple’s son, Pace, embarks on a spiritual quest for the mysterious fifth direction, the “up-down.”

Gifford has lived a life in miles instead of years. He’s never in one place too long, but during moments of cultural upheaval, he has found himself, with an almost Forrest Gump–like serendipity, in the right place at the right time. An autodidact, he’s published poetry, fiction, memoirs, biographies, plays, and screenplays. He turned sixty-eight this year; The Up-Down will be his twentieth novel and his fifty-seventh book. Next year, a new play of his will premiere in New York and a film he wrote will begin shooting in Brazil, with Willem Dafoe as the lead.

At Sarabeth’s in Tribeca, I sat down with Gifford for breakfast the morning after the screening. He joked about the youthful audience, many of whom were younger than the book. “Millennials are discovering Wild at Heart for the first time,” he said. “I’m not quite sure they knew what they were in for.” The Up-Down is, Gifford claimed, the final chapter in the Sailor and Lula story, a story Gifford has told over the course of a quarter century. The collected Sailor and Lula saga runs nearly eight hundred pages and comprises Gifford’s magnum opus, full of recurring characters and settings that center around the titular couple.

Throughout the seventies and eighties, Gifford had been working as a journalist and traveled the world reporting stories. He was under contract to write a book about deep-sea fishing and was staying in a Cape Fear hotel in North Carolina when he heard the voices of Sailor and Lula talking. He called his agent and told him to return the money for the fishing book, because he was onto something. He wanted to write a novel. “My agent almost had a heart attack,” Gifford said. The Twin Peaks producer Monty Montgomery—perhaps better known as the Cowboy from Mulholland Drive—gave Lynch an early copy of the novel. Lynch optioned it, and a year later, they premiered the movie at Cannes.

Decades later, Sailor and Lula’s prelapsarian passion in Wild at Heart resonates with new readers because Gifford doesn’t bullshit; he doesn’t shy away from the hysteria of young romance. Or its growing darkness, for that matter. The novel is a “violent satire,” he told Chicagoist in 2010: “What I wanted Sailor and Lula to represent were innocents. That they were perhaps naive, but innocents nevertheless. And here was all this shit raining down around them … It’s a picaresque. They’re just going down the road, just like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.” Early on, Lula delivers her famous line—“This whole world is wild at heart and weird on top”—as apt an observation now as it was twenty-five years ago.

Gifford was born in 1946, in a hotel room in Chicago, to a racketeer father and a beauty-queen mother. They lived at times in hotels in South Florida, New Orleans, and Havana. Because they moved around so much, Gifford didn’t get much formal education. He learned from late-night noir movies and the strange characters that passed through the hotel lobbies. His father died young, and he and his mother both had to find work. Later, he went to the University of Missouri on an athletic scholarship, but he promptly dropped out and went to Europe to try his hand as a musician and poet. Gifford traveled around for the next few years and then settled in London, amidst the psychedelic movement. It was 1965 and he was twenty-one.

“I have a lot of stories from that time that many people find hard to believe,” he said. He was friendly with Eric Clapton and the Kinks, even met Jimi Hendrix and John Lennon a few times. “I tell these stories not to drop names but to say that the scene was small back then,” he said. “It wasn’t a big deal.”

In 1967, he went to San Francisco during the Summer of Love and was an original writer for Rolling Stone. He fell in with the Beat writers that were still around, including Allen Ginsberg, with whom he became close. They shared a love of Williams Carlos Williams, whose poem “To Elsie” Gifford often cites when describing Sailor and Lula: “The pure products of America / go crazy.”

Over the course of the next few decades, he traveled, writing poetry and nonfiction and befriending outsider writers like Jim Harrison and Larry Brown. He published two novels, but they didn’t sell. Then came Wild at Heart, and his career took off. Ever since, he’s lived in Europe, New Orleans, and New York, but keeps a home base in San Francisco, making a living from his work. When I asked him how he managed to go from an eighteen-year-old kid with a rucksack and thirty dollars in his pocket to a full-time writer, he told me an anecdote about Timothy Leary. (Another old friend, of course.) “Someone asked Tim what he did for money and he said, I just dip my hand into the stream.” And he offered a word of advice: “Be generous and don’t talk down to people.”

A few days after the Wild at Heart event, there was a screening of Lost Highway, Gifford’s other film collaboration with Lynch, at the Museum of the Moving Image. The audience was again packed with young people. I looked for Gifford after the screening, hoping to ask him why the texture and tone of Lost Highway depart so radically from Wild at Heart—but he was nowhere to be found. I asked someone if they’d seen him. “He left already,” she said. “He’s on the road first thing tomorrow.”

Michael Bible has written for the Oxford American, Al Jazeera America, Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Tyrant, and ESPN: The Magazine, among others. He’s currently the senior staff writer at Nerve.com. His novel Sophia will appear in 2015. He lives in New York City.

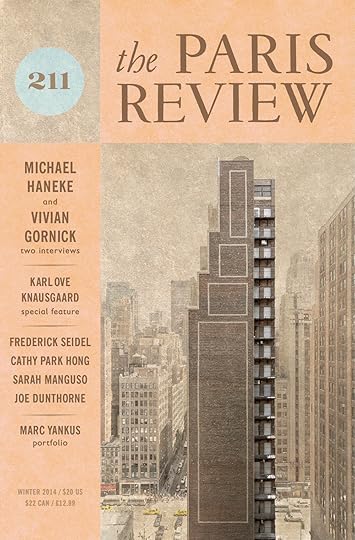

Announcing Our Winter Issue

That photo on the cover comes from Marc Yankus, whose subject is New York buildings: “I can feel the brick, I can feel the hardness and the corners of the building ... the structure, the monolith, the sculpture, the abstract.”

That photo on the cover comes from Marc Yankus, whose subject is New York buildings: “I can feel the brick, I can feel the hardness and the corners of the building ... the structure, the monolith, the sculpture, the abstract.”

In the Art of Memoir No. 2, Vivian Gornick talks about feminism, bad reviews, love versus work, and coming to terms with failure:

I knew I had to stay with it as long as it took to write a sentence I could respect. That’s the hardest thing in the world to do—to stay with a sentence until it has said what it should say, and then to know when that has been accomplished.

And in the Art of Screenwriting No. 5, Michael Haneke reveals the imaginative process behind movies like The White Ribbon and Amour—and why there are no “right” readings of his films:

I would never set out to make a political film. I hope that my films provoke reflection and have an illuminating quality—that, of course, may have a political effect. Still, I despise films that have a political agenda. Their intent is always to manipulate, to convince the viewer of their respective ideologies. Ideologies, however, are artistically uninteresting. I always say that if something can be reduced to one clear concept, it is artistically dead.

There’s also a special triple feature on Karl Ove Knausgaard, with an exclusive excerpt from My Struggle, Book 4; an essay on depression and Dante’s hell; and an exchange with The New Yorker’s James Wood on masculinity and good reasons for writing badly.

Plus new fiction by Joe Dunthorne, Ottessa Moshfegh, Sam Savage, and Saïd Sayrafiezadeh; poems from Sylvie Baumgartel, Jeff Dolven, Cathy Park Hong, Phillis Levin, Jana Prikryl, Frederick Seidel, and Brenda Shaughnessy; and a series of aphorisms by Sarah Manguso.

Get your copy now. And may we add that a subscription to The Paris Review makes a great present? The recipient will receive a postcard announcing your gift with your personal message. Just select the “gift” option when you check out.

American Grotesque, and Other News

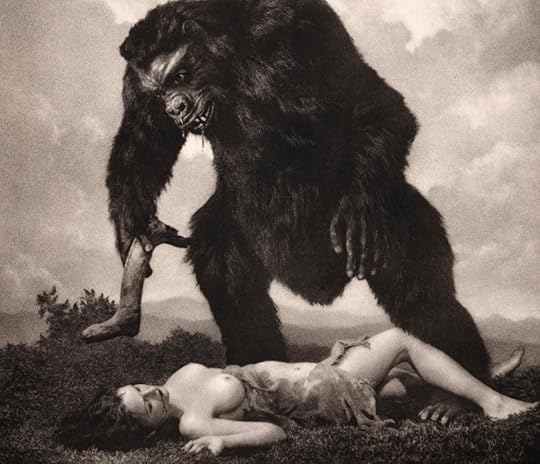

William Mortensen’s L’Amour (1932) doubles as the cover of a new book about him, American Grotesque.

Don DeLillo rereads his own opus, Underworld, seventeen years after its publication. (“Great fucking line,” he’s written next to “The subway seals you durably in the stone of the moment.”)

In the thirties, William Mortensen was one of the most celebrated photographers in the nation—his pictures were “unabashedly theatrical, bizarre, and often louche.” What sank his reputation: a critical tiff with Ansel Adams.

The Chinese State Administration for Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television has moved to ban wordplay “on the grounds that it breaches the law on standard spoken and written Chinese, makes promoting cultural heritage harder and may mislead the public—especially children.” (An example of the now forbidden fruit: “replacing a single character in ke bu rong huan has turned ‘brook no delay’ into ‘coughing must not linger’ for a medicine ad.”)

While we’re on censorship: In the quest for G-rated moon landings, NASA used to go to great lengths to scrub astronauts’ profanity from its transcripts. In the case of one particularly salty spaceman, they went further—they had him hypnotized. “A psychiatrist put the idea in his head that he would rather hum when his mind wandered.”

On the history of fairy tales: “In the coded language of symbol and metaphor they chart the journey from childhood to adulthood. The Russian commentator Eleaser Meletinksji wrote, ‘It is even possible to say that the fairy tale begins with the break-up of one family and ends with the creation of a new one.’”

November 30, 2014

This Week on the Daily

Max Slevogt, Der Sänger Francisco d'Andrade, Zeitung lesend, 1903.

“I am writing from a place you have never been, / Where the trains don’t run, and planes / Don’t land … ” Remembering Mark Strand.

*

Justin Taylor talks to Shelly Oria about her new book, New York 1 Tel Aviv 0. “What I’m trying to do, not only as a writer but as a human—is challenge this idea of either-or, hang out a bit in the in-between space.”

*

Paul Muldoon rereads his first book of poetry, 1971’s Knowing My Place …

*

… And Alec Soth annotates his monograph Niagara, including new photographs.

*

“You can look at a piece of mine and think that it’s a benign exploration, but I like to think there’s an edge underneath it all in terms of certain commentaries on relationships.” An interview with Gladys Nilsson.

*

Plus, Sadie Stein on Thanksgiving traditionalists, and Simon Rowe’s winning entry from our Windows on the World contest.

November 29, 2014

Mark Strand, 1934–2014

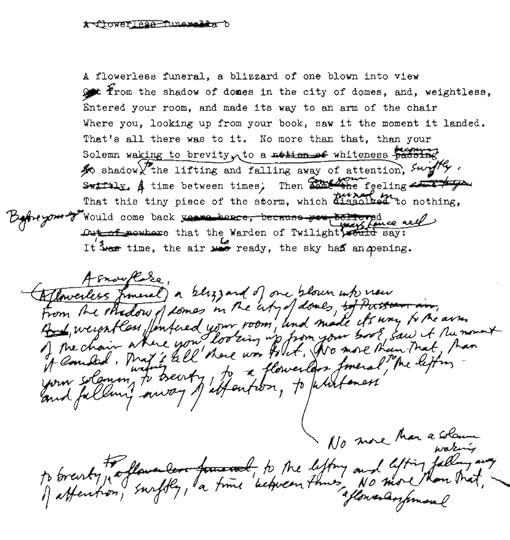

A manuscript page from “A Piece of the Storm,” a poem from A Blizzard of One.

When I read poetry, I want to feel myself suddenly larger … in touch with—or at least close to—what I deem magical, astonishing. I want to experience a kind of wonderment. And when you report back to your own daily world after experiencing the strangeness of a world sort of recombined and reordered in the depths of a poet’s soul, the world looks fresher somehow. Your daily world has been taken out of context. It has the voice of the poet written all over it, for one thing, but it also seems suddenly more alive… —Mark Strand, The Art of Poetry No. 77, 1998

Mark Strand died today at eighty, we were sorry to learn. When Wallace Shawn interviewed him for The Paris Review in 1998—a year before he won the Pulitzer Prize for his collection Blizzard of One—Strand described his relation to death: “It’s inevitable. I feel myself inching towards it. So there it is in my poems. And sometimes people will think of me as a kind of gloomy guy. But I don’t think of myself as gloomy at all. I say ha ha to death all the time in my poems.”

And death was arguably Strand’s great theme—few poets have written more acutely or more movingly about the chasm at the end of life. Which is not to say that he was excessively dour or bleak; the sense of isolation in his work is often leavened by light and feeling. Strand saw poetry as a humanizing influence in an increasingly inhumane world. He told Inscape a few years ago:

If every head of state and every government official spent an hour a day reading poetry we’d live in a much more humane and decent world … Poetry delivers an inner life that is articulated to the reader. People have inner lives, but they are poorly expressed and rarely known. They have no language by which to bring it out into the open. Two people deeply in love can look at each other and not have much to say except “I love you.” It gets kind of boring after awhile—after the first ten or twenty years … When we read poems from the past we realize that human beings have always been the way we are. We have technological advancements undreamt of a couple thousand years ago, but the way people felt then is pretty much the way people feel now. We can read those poems with pleasure because we recognize ourselves in them. Poetry helps us imagine what it’s like to be human. I wish more politicians and heads of state would begin to imagine what it’s like to be human.

His poem “After Our Planet,” from our Winter 1992 issue, is a perfect read for the occasion. Strand seems to be speaking from the afterlife in it, from a place of wondrous stillness, inaccessible to us:

I am writing from a place you have never been,

Where the trains don’t run, and planes

Don’t land, a place to the west,

Where heavy hedges of snow surround each house,

Where the wind screams at the moon’s blank face,

Where the people are plain, and fashions,

If they come, come late and are seen

As forms of oppression, sources of sorrow.

This is a place that sparkles a bit at 7 P.M.,

Then goes out, and slides into the funeral home

Of the stars, and everyone dreams of floating

Like angels in sweet-smelling habits,

Of being released from sundry services

Into the round of pleasures there for the asking—

Days like pages torn from a family album,

Endless reunions, the heavenly choir at the barbecue

Adjusting its tone to serve the occasion,

And everyone staring, stunned into magnitude.

Read the whole poem here.

November 28, 2014

Staff Picks: Absolution, Antipodes, Air Raid

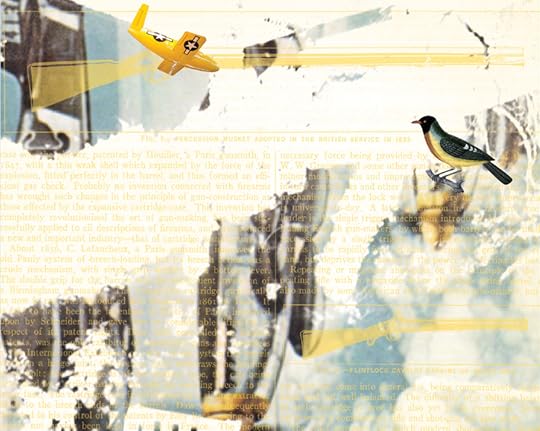

From the cover of the new translation of Alexander Kluge’s Air Raid

Last night, I finished Gerald Murnane’s The Plains and this morning I started reading it again. It’s the story of a filmmaker who travels from the coast of Australia into the plains of the interior, where instead of flyblown pit stops he encounters a society of vast estates—latifundia meets British manor house—whose culture is based on avant-garde poetics and the art of heraldry. The plainsmen are melancholy philosophers whose koans would have made T. S. Eliot proud: “I’ve spent my life trying to see my own place as the end of a journey I never made,” one says into his beer. Murnane is a careful stylist and a slyly comic writer with large ideas. I know it’s the antipodes, but it’s hard to fathom why he isn’t a little better known here. —Robyn Creswell

I’ve been caught up in Alexander Kluge’s masterpiece Air Raid (1977), finally available in English—an unsettlingly oblique remembrance of the events of April 8, 1945, when Americans carpet-bombed Halberstadt, a German town of no particular significance to the war effort. Eighty percent of the place was destroyed and thousands died; Kluge, who lived there, was thirteen at the time. Air Raid is composed of fragments: diagrams, photographs, interviews, vignettes of survivors. In Kluge’s affectless prose, the manager of a bombed movie-theater watches as her patrons’ corpses are boiled by the hot water gushing from an exposed pipe; a confused cemetery groundskeeper goes to sleep in an open grave. The book is part fiction and part reportage, but Kluge makes no effort to say which is which; in fact, many of its more explicitly documentary sections, such as a long interview with an American brigadier, are entirely fabricated. It’s an affecting puzzle about the destabilized narratives of war. The reader has to construct some semblance of a story from the rubble. —Dan Piepenbring

While everyone is talking about “Serial,” you should be listening to another “This American Life” alum’s podcast, “StartUp,” in which Alex Blumberg attempts to launch his podcast startup. (He’s aware of how meta this is.) Blumberg makes a failure of a pitch to venture investor Chris Sacca; he compares the search for a business partner to the awkwardness of the dating world. The podcast is a fascinating and insightful look at the nature of business.. As Blumberg reflects, “You think it’s about numbers and bottom lines—but really it’s just about raw feelings?” —Justin Alvarez

Scott McClanahan has a new essay on The Fader’s website about how his love for Little Jimmy Dickens, and his wife's dislike for the diminutive country star, broke up their marriage—or at least that perhaps he should have taken her antipathy for Dickens as a sign. The essay traces his understanding of an aspect of his life through the filter of music, but it’s not the kind of autobiographical piece that retrospectively bestows wisdom and clarity on one's life—the artificiality that ruins so many memoirs. McClanahan's writing, both fiction and nonfiction, has the feel of storytelling and often of catharsis; he writes a form of ballad (or, in this case, maybe an antiballad) that country music does so well. Of Dickens's most famous song, “May the Bird of Paradise Fly Up Your Nose,” McClanahan writes, “It was a song not interested in telling you about the mind of the insane, but one that wanted to produce that state of mind in the listener. It was a spell, a fever, a curse.” That’s a good description of the way McClanahan crafts a tale, too. —Nicole Rudick

As a kid, I would watch Forrest Gump every day. I don’t remember why, but I do remember the day the VHS tape started to deteriorate: as Forrest ran out of the football stadium, the crowd yelling for him to stop, the sound morphed out of sync with the image. I enjoyed this: it was a kind of personal imprint, like a folded page in a well-read book. I thought of this moment as I made my way through Nicholas Rombes’s excellent and nightmarish The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing, about a writer’s search for a lost filmmaker. Through various conversations between the writer and filmmaker—who has destroyed many of his own films—Rombes explores the thin line between fiction and reality, “something there, in between the frames, something that wasn’t quite an image and wasn’t quite a sound ... an impossibility that, because it expressed or represented a new way of being, had to be destroyed.” As my copy of Forrest Gump further deteriorated, I would have to describe the missing scenes whenever my friends and family watched the tape. Over time, my descriptions transformed into something much different than the scenes themselves had been, as a DVD copy later proved. Rombes’s novel is a love letter to this art of misremembering: these “destroyed films” become as real as any film playing in a theater near you. —J.A.

Announcing the Winner of Our Windows on the World Contest

Earlier this week, we announced the five finalists in our Windows on the World contest; today we’re happy to say that the winner is Simon Rowe, with his view from Himeji City, Japan. Simon will have his view sketched by Matteo Pericoli. Congratulations to him, and many thanks to all who entered!

Simon Rowe

Simon Rowe, Himeji City, Japan

Time has gathered Japan’s villages into towns and cities, even turned some into metropolises, but the cho, or neighborhood, remains the heart and soul of the nation.

Mine resembles an overcrowded circuit board with its dense clusters of houses spanning a century in design and its winding pathways, which deliver children to school, businessmen to bus stops, and elderly to their kitchen gardens. This is Kamiono-cho, in Himeji city—where the westward sprawl that begins in Osaka finally runs out of steam.

Bamboo grows as thick as a man’s leg in the forests beyond the neighborhood, lofty and mesmerizing when the valley winds blow. In Autumn, the smell of burning rice chaff reaches through the window, signaling the end of the harvest season and the start of the festivals that celebrate its bounty. Taiko-drum volleys rattle my window, just as the earthquakes do.

Snow dusts the rooftops in winter. Through the opened window, knife-edged winds carry a whiff of Siberia—chilling, yet invigorating. Spring sees cherry blossoms garnish the neighborhood and family picnics mushroom beneath them. Then the blossoms fall, like the brief and beautiful life of a samurai, with the first spring rains. Summer arrives and the window is shut to the whining insects and the suffocating humidity, which descend on the city. The pane rattles once more with the typhoons of late summer; TV antennas waggle on tiled roofs, momentarily lost to the rain.

The old neighborhood, once famous for strawberry growers, is vanishing. Where fruit grew, model homes now stand. Outside them, housewives gather on dusk to chew over the day’s proceedings and await their children’s return from school. Long after dark, the buses will disgorge their tired husbands, who will drift heavy-hearted back to their homes and sleeping families.

Meet the New Black Friday (Same as the Old Black Friday), and Other News

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The mystery novelist P. D. James is dead at ninety-four. “‘When I first heard that Humpty Dumpty fell off the wall,’ she was fond of saying, ‘I immediately wondered: Did he fall — or was he pushed?’” (James was interviewed for The Paris Review’s Art of Fiction series in 1995.)

Black Friday is hell. But now there is a new hell, for there is a New Black Friday. (It involves Walmart and money.)

“In recent years, not just in novels but in movies, television, poetry, video games and the visual arts, drones have taken on a life of their own. As a character, they are menacing, melancholy or gallant; beastly, blind, snub-nosed, noisy and fast—Predators and Reapers in real life, ‘Helicarriers’ in Hollywood. They are the oversize hook at the end of a joystick, a militarized, antiseptic video game characterized by precision; or they are a weapon system proliferating at a breathtaking rate, and leaving a trail of destruction behind. They show off the military talent of their users, or they are an expression of unbridled hubris. They represent protection or extermination—and they carry out both things at once.”

In 1948, an eleven-year-old girl named Sally Horner was abducted—and the details of the case bear more than a passing resemblance to Lolita.

Something to ponder over leftovers: the literature of Thanksgiving. (From Mark Twain: “In the island of Fiji they do not use turkeys; they use plumbers. It does not become you and me to sneer at Fiji.”)

November 26, 2014

William Meredith’s “Parents”

James Vaughan, via Flickr

INTERVIEWER

Some of the poems in The Cheer revolve around a single, central, and somewhat mysterious idea. I’m thinking of poems like “Parents”…

MEREDITH

I’d love to tell you the story about “Parents” because it occurred one time after I’d gone to a Thanksgiving dinner where a couple I’m very fond of had three surviving parents. The three parents seemed to me valid, charming, interesting people, about my own age, and to their children they seemed, as parents normally do, embarrassing, stupid, tedious, albeit lovable. I saw my friends suffering and I remembered such suffering. The poem says essentially, “It is in the nature of things that one’s own parents are tacky, and this should give you compassion because your children will find you tacky.” The poem came out of that particular experience.

—William Meredith, the Art of Poetry No. 34, 1985

What it must be like to be an angel

or a squirrel, we can imagine sooner.

The last time we go to bed good,

they are there, lying about darkness.

They dandle us once too often,

these friends who become our enemies.

Suddenly one day, their juniors

are as old as we yearn to be.

They get wrinkles where it is better

smooth, odd coughs, and smells.

It is grotesque how they go on

loving us, we go on loving them

The effrontery, barely imaginable,

of having caused us. And of how.

Their lives: surely

we can do better than that.

This goes on for a long time. Everything

they do is wrong, and the worst thing,

they all do it, is to die,

taking with them the last explanation,

how we came out of the wet sea

or wherever they got us from,

taking the last link

of that chain with them.

Father, mother, we cry, wrinkling,

to our uncomprehending children and grandchildren.

Dressing

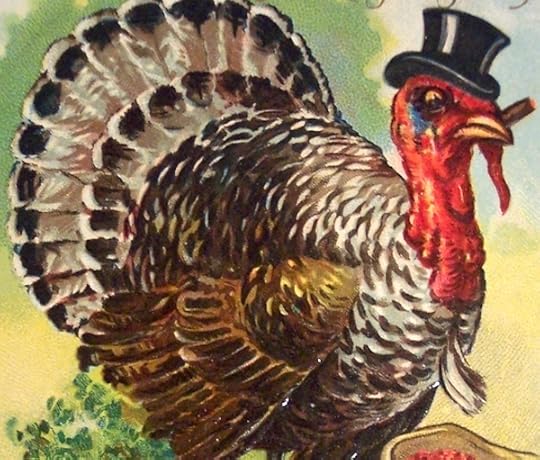

“Boys, I feel I’m going to a change of climate.” A vintage Thanksgiving card.

As fans of holiday ephemera know, there are several primary genres of weird, old-timey Thanksgiving cards. There is the Greedy Child. There is the Doomed Turkey. There is the Turkey in Vehicle, which is sometimes a corncob car. There is the Anthropomorphic Root Vegetable. It hardly needs saying that Thanksgiving pinups are a thing unto themselves. Sexy Pilgrims, under-dressed squaws, and women cooking in lingerie and filmy cocktail aprons are all fairly ubiquitous.

By far, my favorite subgenre is that of the Urbane Turkey. This foppish specimen is usually in evening dress, so as to indicate his couth. Needless to say, he sports a top hat. Sometimes a monocle or a cigarette. All in all, he has the trappings of a big-screen, rich nincompoop, which I suppose added a certain glee to his consumption.

The Urbane Turkey is not always complacent. Sometimes he’s a sharp. He’s in the know. This Urbane Turkey is the turkey who knows where to find the best feed and the keenest peahens. As befits his man-of-the-world air, he smokes a cigar; and his citified duds are less Union Club than pool hall. This tom doesn’t take any wooden nickels; he sees the way the wind’s blowing and he’ll be out on the next train, before the axe is even sharpened. He doesn’t need pardoning; he makes his own luck.

You don’t need me to point out how alienated we are from our food sources, to general detriment. Certainly, there couldn’t be anything less urbane than the case of shrink-wrapped butterballs (or even free-range heritage birds) that greets us come late November. I guess it would be easy to say that as a result, we have less respect for our food. But on the other hand, we also don’t dress it in outfits and mock it.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers