The Paris Review's Blog, page 643

November 17, 2014

Tools of the Trade

Foote‘s nib of choice. Photo: Elizabeth, via Flickr

INTERVIEWER

I’ve heard that during the middle of writing The Civil War you bought all the dip pens left in the United States.

FOOTE

My favorite pen-point manufacturer had all but gone out of business—Esterbrook. I was running out and fairly desperate. On Forty-fourth Street just east of the Algonquin Hotel, on the other side of the street, there used to be an old stationery shop, all dusty and everything, and I went in there on the chance he might have some. He looked in a drawer. He had what I wanted—Probate 313. I bought several gross of those things, so I’ve got enough pen points to last me out my life and more. Another problem is blotters. When I was a kid and when I was writing back in the forties on into the fifties, you could go into any insurance office and they had stacks of giveaway blotters for advertising.

INTERVIEWER

What precisely is a blotter?

FOOTE

This is a blotter [pointing] and if you haven’t got one you’re up the creek. You use the blotter to keep the ink from being wet on the page. You put the blotter on top and blot the page. I was talking about blotters in an interview, what a hard time I had finding them, and I got a letter from a woman in Mississippi. She said, I have quite a lot of blotters I’ll be glad to send you. So I got blotters galore. Ink is another problem. I got a phone call from a man in Richmond, Virginia who had a good supply of ink in quart bottles. I got three quarts from him, so I’m in good shape on that.

INTERVIEWER

Do you reckon you’re the last writer to be using dip pens in the United States?

FOOTE

There’s probably some other nut somewhere out there doing it.

—Shelby Foote, the Art of Fiction No. 158, 1999

Shelby Foote was born on November 17, 1916, and died in 2005, six years after this interview was published. Though he was a prolific novelist, he remains best known for his three-volume history of the Civil War.

His is one of my favorite Writers at Work interviews, and not coincidentally it’s probably one of the longest—Foote’s three (!) interlocutors find him in a loquacious and expansive mood, such that almost whenever he opens his mouth he seems to speak in wry, eloquent, discursive paragraphs. He declaims on everything from pajamas to the Ku Klux Klan, and he appears to have known more or less every writer of relevance; his anecdotes include the likes of Faulkner, Hemingway, O’Hara, Kubrick, and Walker Percy, among others.

He also relishes the role of gentle, aging eccentric, as evidenced in the passage above. I’ve just spent an embarrassingly long while trying to find the name of the defunct stationery shop he references—no luck. I can report, though, that the Esterbrook Probate 313 is readily available for all your dipping needs, even as blotter paper seems now entirely relegated to the realm of LSD paraphernalia.

The Esterbrook Pen Manufacturing Company, founded by Richard Esterbrook in 1858, was once the oldest and largest manufacturer of steel pens in the United States. A midcentury brochure (“INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT ESTERBROOK STEEL PENS”) notes that the company once turned out more than two hundred million pens a year, “used in every civilized country in the world.” The factory went under in 1972.

“You have to communicate sensation,” Foote said of the writer’s mission,

the belief in what life is, what it’s about, and you do it through learning how to handle a pen. That’s the reason why I have always felt comfortable with the pen in my hand and extremely uncomfortable having some piece of machinery between me and the paper—even a typewriter let alone a word computer, which just gives me the horrors.

A Brief History of Insect Control

Long before environmentalism, Charles Valentine Riley had a problem with pesticide.

Spraying the capitol with pesticide, 1886.

In science, good ideas often trump great ones. Take, for instance, Charles Valentine Riley, the most prescient scientist of whom you’ve never heard. The man had a great idea. Then came Leland Howard, his prickly and calculating successor. He had the good one.

These men were late nineteenth-century entomologists, a humble vocation by the standards of the day. But the U.S. Department of Agriculture—new then, having been formed in 1862—asked them to accomplish something not so humble: they were to learn everything there was to know about agricultural pests, and then to destroy them. The intended beneficiaries of this project were panicked farmers whose fields were being decimated by insect invasions. Riley and Howard were charged with exterminating the very creatures they studied. If the irony registered, they never said so.

Riley was the older of the two gentlemen. He’d assumed leadership of the U.S. Entomological Commission in 1876 after spearheading the country’s first Grasshopper Commission. His big idea—the great one—was to merge the observational folk-wisdom of everyday farmers with the financial largesse of the federal government to help insects kill insects. Biological control, we now call it. If the concept of exterminating insects with insects seemed moony, American farmers were game. They’d seen it happen on the ground and they were desperate. Between 1860 and 1900—a time when agriculture began to pursue high-yielding monoculture in earnest—armies of chinch bugs, locusts, San Jose scales, boll weevils, Colorado potato beetles, and Hessian flies capitalized on the smorgasbord, moving steadily eastward and shredding the foodscape with biblical power. One Illinois farmer reported that there were so many locusts in his fields that “the ground seemed to be moving.” Pick up an agricultural report from the period—you know, just pick one up!—and you’ll find that an apocalyptic strain of agrarian rhetoric echoed across America’s amber waves of grain.

I’ve read nearly every word Riley wrote, at least every available report and letter, and my overwhelming impression is that the guy was one charming cat. He rode his bike all over D.C. for exercise. He had six kids and doted on them. Like many entomologists, he was a brilliant illustrator of insects. When he taught entomology classes at the University of Missouri in the 1870s, he was so thrilled to be talking shop that he would draw insects on the board with both hands at once. He grew his hair into a cascade of curls and his students adored him. I have no hard proof, but there was something about Riley’s zest for life in general—and for insect life in particular—that dissuaded him from the easy answer to the insect problem, the one that the power brokers of the day wanted: chemicals.

Riley, 1876.

Riley was instinctively wary of these new concoctions—amateurish compounds of arsenic and lead and kerosene—being sprayed and dusted over arable land and healthy soil. He had never, he wrote, “had much faith in the application to the plant or the insect of any chemical mixture.” It was the insects’ natural enemies, by contrast, “that carry on their good work most effectually.” (In this respect Riley stood on the shoulders of his mentor, Benjamin Walsh, an outspoken entomologist who deemed chemical washes “hellbroths” and spent columns of ink lambasting them in The American Entomologist.) Riley wasn’t categorically opposed to the available sprays of the day—Paris Green and London Purple, to name the most popular—but he decided that it was in everyone’s best interest to keep calm, do some fieldwork, and see if nature might do the job first. Charles Darwin, for one, sent him a little fan note.

Riley knew his way around a farm. He cut his teeth in the wheat fields of the Midwest, where he worked himself to the point of exhaustion helping farmers manage a microscopic root insect called phylloxera. His proposed solution was to introduce mites that “prey extensively on this root-inhabiting type.” The results were decent, but no knockout. Riley drew upon this research to help French vintners, whose vineyards were being devastated by phylloxera; he suggested that they graft a native grape onto a phylloxera-resistant American vine. This advice saved France’s wine industry. In 1884 Riley had a French Grand Gold Medal pinned to his lapel.

An illustration by Riley from the 1885 United States Entomological Commission Report on the Cotton Worm.

Then he hit pay dirt at home. In 1886 an Australian insect called the cottony-cushion scale—an adult female looks like a tiny puff of cotton—came over on some acacia tree saplings and sent the nation’s orange industry into a tailspin, invading California’s citrus groves. Riley, who was by this time head of the Department of Agriculture’s entomology division, sent an insect collector to find the scale’s natural predators. By January 1889, the collector had an answer: Vedalia beetles. California entomologists bred and released 10,555 of them into California’s orange groves. Within months the cottony-cushion scale had effectively vanished and the industry recovered.

It was the world’s first commercial-scale triumph of biological control. The New York Times called Riley’s plan “a complete success,” and Riley, beside himself, began centering the Division of Entomology’s research agenda on the promise of biological control. But those plans came to a tragic halt on September 14, 1895. Riding his bike to the Smithsonian to look at butterflies, Riley hit a paving stone, pitched over the handlebars, and died from a head injury. (Oddly enough, years earlier his mentor, Walsh, had been run over by a train.)

Riley’s sketches of the Vedalia beetle.

Leland Howard, Riley’s longtime second-in-command—openly disgruntled for having been treated “like a clerk”—took charge of the Division of Entomology. His training took place in a Cornell laboratory rather than a Missouri wheat field, and he quickly developed different ideas about effective insect control. This was the Progressive Era, and Howard, a good progressive, believed that problems should be identified, experts amassed, and the most potent solutions applied. For a federal entomologist accountable to the general public, this meant one thing: chemicals.

Riley’s drawings of the Colorado Potato Beetle.

To be fair, Howard gave biological control a shot. Soon after assuming Riley’s position, he targeted the gypsy moth, whose larvae had come to Massachusetts by way of a French suitcase back in the 1860s. By the 1890s, they were denuding trees throughout New England. Howard traveled to Europe and researched the moth’s natural enemies. He returned with several possible predators, released them, and prayed for success—but to no avail. He never found his Vedalia beetle. The gypsy moth continued to decimate the region’s towering hardwoods, leaving Howard, as one critic put it, with “egg on his face.”

So Howard, suddenly attuned to the political benefits of expediency, did something remarkably savvy. He promoted insecticides by highlighting a far more pervasive danger: mosquitoes, which had, after the 1900 discovery that they were linked to malaria, become the preeminent pest in America. Concern for the nation’s agricultural prosperity yielded easily to public health anxieties, and Howard was well aware of the transition—he bombastically announced the onset of a “mosquito plague” and quickly wrote Mosquitoes: How They Live; How They Carry Disease; How They Are Classified; How They May Be Destroyed. In that volume, he made an airtight case: the only way to kill the Anopheles mosquito, and thereby to protect and serve the citizenry, was to blanket the nation with a combustible hydrocarbon mist of kerosene.

There’s no doubt that Howard was right. Kerosene worked. With the Insecticide Act of 1910, mosquito spraying became not only standardized, but also relatively safe. Then came World War I. In yet another ingeniously calculating move, Howard let the War Department know that, with mites and mosquitoes and lice endemic to trench warfare, entomologists armed with chemical sprays could be just as critical to the war effort as soldiers armed with rifles. “Warfare against insect life,” he explained, required the Division of Entomology to expand its arsenal to include benzene, carbolic acid, creosote, alkaline soaks, and sulfur baths. Medical entomology, as they called it, was born.

And surely, the thinking went, what worked in the trenches would work in the fields at home. While chemical treatments were administered in Europe, farmers in the United States—men and women burdened with provisioning the war effort—had no time to dither with the trial-and-error headache of biological control. Castor beans (used for castor oil to lubricate airplane engines), beef, and wheat showed up in ample quantities because of the arsenical compounds and cattle “dipping vats” designed to keep insects at bay. In the decade after the war, the trend continued apace: farmers fought the boll weevil with ten million pounds of carbon arsenate dust and dropped bombs of Paris Green from airplanes and blimps over corn fields. An arsenic-based mosquito larvicide came to market, and companies such as DuPont and the Hercules Powder Company began to lure farmers into the quick-fix fold. A kind of path dependency set in.

And surely, the thinking went, what worked in the trenches would work in the fields at home. While chemical treatments were administered in Europe, farmers in the United States—men and women burdened with provisioning the war effort—had no time to dither with the trial-and-error headache of biological control. Castor beans (used for castor oil to lubricate airplane engines), beef, and wheat showed up in ample quantities because of the arsenical compounds and cattle “dipping vats” designed to keep insects at bay. In the decade after the war, the trend continued apace: farmers fought the boll weevil with ten million pounds of carbon arsenate dust and dropped bombs of Paris Green from airplanes and blimps over corn fields. An arsenic-based mosquito larvicide came to market, and companies such as DuPont and the Hercules Powder Company began to lure farmers into the quick-fix fold. A kind of path dependency set in.

By the time Leland Howard retired, in 1927, the United States was a full-fledged insecticide nation. When he died in 1950, DDT had replaced his career-launching kerosene as the mosquito killer of choice. The last vestiges of Riley’s biological-control regime were fading from the public memory. And wouldn’t you know it? In his retirement, Howard took up cycling.

James McWilliams is a writer living in Austin, Texas. He teaches at Texas State University and is the author of Just Food: Where Locavores Get It Wrong and How We Can Truly Eat Responsibly .

Banned Books

An illustration from Once Upon a Potty.

Once Upon a Potty was written in 1975 by the Israeli author and illustrator Alona Frankel to help her son toilet train. (Its Hebrew title is Sir Ha-Sirim, literally “Potty of Potties.”) Since it was translated into English in 1980, it’s never gone out of print, and now it’s regarded as a picture-book classic, a helpful resource for the parents of young children.

It was banned in my house. My mother disliked the use of euphemisms she deemed babyish—wee-wee, potty, “a hole to woo-woo from”—and illustrations she found “creepy” and “disgusting.” I can still recall first hearing what would become one of her most oft-repeated phrases: “I don't care for that at all.” She sniffed at households that owned the book and curled her lip when we saw it on store shelves.

As a result, Once Upon a Potty took on the luster of the taboo. Like a nineteenth-century schoolboy with a French postcard, I would read it—or, anyway, look at it—furtively whenever I was unobserved: at other toddlers’ houses, in the children’s room of the library, at the local Y where I did tumbling. Particularly shocking to me was the final illustration: the triumphant coil of tempera feces in a puddle of yellow urine. And the accompanying text! Exuberantly babyish, frankly scatological, my mother's nightmare incarnate. “Bye-bye wee-wee,” it reads as the excrement disappears down the toilet. “Bye-bye woo-woo.”

Beyond its scandalous subject matter, I was struck by the fact that the protagonist, Joshua, had a full head of hair: I was bald. What Freud would have to say about all this is an open question. (There is surprisingly little scholarly work devoted to Freudian readings of the Frankel oeuvre.)

Not long ago, I was babysitting for a friend’s toddler. And there, on the shelf, I spotted it: a smiling, naked baby, seated on a chamber pot, gaily ringed with forget-me-nots. Once Upon a Potty. To read it now, I thought, would be creepy, or deviant, even. And yet throughout the following hours it preyed on me. I was wracked with irrational anxiety: What if my charge wanted me to read it aloud? I couldn’t; it would be akin to reading pornography.

In the end, it didn’t come to that. When he brought me a stack of picture books, Once Upon a Potty was not in it. Instead, there was a copy of Everybody Poops. I moved it covertly to the bottom of the pile. I didn’t want to read it—but there was no need to turn it into something forbidden.

Painting the Invisible Hippo, and Other News

Peter Paul Rubens, Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, 1616.

A new book looks at the history of the literary feud—with an abundance of ripe examples, including “the battle between Bevis Hillier and AN Wilson in the 1980s. Wilson had published a devastating review of Hillier’s authorized biography of John Betjeman, calling it ‘a hopeless mishmash.’ When Wilson announced his own biography of Betjeman, he received a letter from a mysterious French woman including the copy of an unpublished letter from Betjeman to Honor Tracy, describing their affair. Wilson could not resist including it in his book, and when the biography came out Hillier gleefully revealed that the letter was an acrostic, spelling out ‘AN Wilson is a shit.’”

Today in evolving forms of literacy: Emoji as language. On Twitter, emoji are now used more frequently than hyphens, tildes, and the numeral five. Whither emoji-speak? And does this wordless tongue have any antecedents? (“In 1974, the American Institute of Graphic Arts, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Transportation, designed a new system of symbols to be used in airports around the world in response to the increase in global travel … the design committee also made the following deduction: ‘We are convinced that the effectiveness of symbols is strictly limited.’ ”)

In 1616, Peter Paul Rubens painted a hippo. Problem: He had never laid eyes on a hippo. How did he do this?

A debut, of sorts, for Denis Johnson—as a visual artist. “His sketch is what I like to think of as three-quarters Basquiat, one-quarter ninth-grade geometry class.”

Writers and musicians seem to collaborate constantly, and yet it’s seldom a collaboration in the truest sense of the word. “Superficially, these collaborations fit into a pattern of writing and music as natural partners, one—to paraphrase Katharine Hepburn on Astaire and Rogers—providing the other with class, the other giving sex appeal … Perhaps tellingly, however, such liaisons tend to be one-off or short-lived … A novelist, playwright or poet providing words for someone else to turn into music and perform, although it is a model inherited from opera and musicals in earlier eras, is now surprisingly rare.”

November 15, 2014

Shep and Dorothy

A husband-and-wife team and their influential midcentury designs.

From Dorothy and Otis: Designing the American Dream.

Lucky is the designer who can see in both two and three dimensions. Luckier still is she or he to be married to someone with equal gifts—especially if that mate is a collaborator and not a competitor. So appears to have been the case with Dorothy and Otis Shepard, whose enviable creative lives have been captured in the absorbing, moving, and lushly illustrated new book Dorothy and Otis: Designing the American Dream, by Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel.

Both Dorothy and Shep (his nickname since childhood) got their start as commercial artists during San Francisco’s billboard boom of the 1920s. The Federal Highway Act, signed in 1921, helped fund the expansion of U.S. roadways, and advertisers took the opportunity to reach audiences beyond the traditional black-and-white pages of mail catalogs by posting colorful advertisements along America’s highways. Shep, a veteran of World War I, was a man of great adventure, with a strong and lasting interest in the theater. He was well regarded as a commercial painter while employed as an art director at Foster & Kleiser Outdoor Advertising Company, a top Bay Area agency of the period. In 1927, he wisely hired the gifted and highly praised Dorothy Van Gorder straight out of the California School of Arts and Crafts, from which she had graduated in only three years, as valedictorian. According to family lore, Dorothy was unabashedly outspoken (and just plain unabashed—she was once evicted from an apartment for sunbathing nude on the roof), and it cost her the Foster & Kleiser job, but almost as soon as she was let go, she was rehired for her prized skills. Hathaway and Nadel write that either in spite of or because of Dorothy’s brashness, Shep, the “raconteur,” soon began courting the “young bon vivant.”

And so their joint artistic adventure began—most markedly with a honeymoon in 1929 to Paris, Venice, Zurich, and Vienna. While there, they purchased Bauhaus furniture and had the good fortune to meet the great modernist Joseph Binder, who was a leader in the European abstract graphic style. “Shep and Dorothy already wanted their work to convey meaning through compositional structure—instead of realism,” write Hathaway and Nadel, but Binder’s reduction of “an image to a series of shapes and forms and [integration of] typography into his pictures” helped refine their approach to design and illustration. Both Dorothy and Otis had been following the modernist movement with great interest back home, but seeing this work and the new techniques in person and to scale had a profound and lasting effect on them.

The Shepards were quick studies; they promptly took up and mastered the tools and tastes of their European counterparts on their return to San Francisco. Chief among these was the airbrush technique that’s now synonymous with the visual voice of posters and advertising of the era. It’s a style that’s widely copied in design today in ways that are nostalgic but that continue to look fresh. The subtle fade and gradient effect of the airbrush came to distinguish Dorothy’s and Shep’s work in the 1930s, in both individual and collaborative projects for freelance clients. With this new, very commercial style, Shep became an “avant-garde populist in graphic design, bringing the new aesthetic to all regions of the country,” while Dorothy enjoyed a career that “made her the earliest and most well established female modernist designer in North America.”

It was Shep’s thirty-year working relationship with the chewing-gum giant Wrigley that brought unimaginable opportunities for both him and Dorothy. P.K. Wrigley and Shep had a lifelong friendship that, while sometimes contentious, seems to have been full of good faith. Wrigley not only had Shep art direct all areas of his chewing-gum empire, he also entrusted him to reimagine Catalina Island, which his father had purchased years earlier, as a tourist destination. Shep gave up all other freelance work to focus on the Wrigley account, which took him to Chicago for half the year. Dorothy assisted him as a ghost designer on some of these well-known projects and continued to take on clients of her own back in New York, where the newlyweds had relocated after the Chesterfield company paid for them to live and work for six weeks while creating an original campaign for their cigarette brand. Shep’s highly memorable graphic packaging for the ubiquitous, all-American chewing gum and the all-so-familiar advertising for the brand (think the Doublemint Twins!) is so a part of the fabric of our everyday design culture that it embarrassed me not to know Shep’s name, let alone that of his unsung wife and frequent collaborator.

With Catalina, the Shepards enjoyed four years of unparalleled creative freedom to invent a vacation paradise, one that, according to Shep’s vision, would be as charming and romantic and as much of a draw as any of the well-loved European vacation destinations of the day. (And it was: among the island’s visitors were Betty Grable, Joan Crawford, Johnny Weissmuller, and Cecil B. DeMille.) Shep developed the Early California Plan, which provided guidelines for local shop owners about how they could improve their business through a smart, consistent, island-wide design vision. Dorothy was fastidious in her research of the Mexican and Native American influences on the island, and this inspired her choices of color, typography, architectural detail, and even the uniforms for all of Catalina’s tradespeople. She created a system of dimensional signage that was consistent in its use of typography and illustration style. All of these efforts by the visionary couple had a subliminal unifying effect that contributed to its financial success.

In 1936 and ’37, Shep oversaw the complete image overhaul of P.K.’s beloved Chicago Cubs and of Wrigley Field itself. He redesigned the field’s signage and scoreboards, tickets, concession stands, and bleachers, and his new players’ uniforms set the standard for the shape and tailoring of all modern baseball teams. The book includes page after page of Shep’s richly colored and dynamic midcentury Cubs programs and yearbook covers, created with his signature airbrush technique. He’s responsible, too, for the print materials for the All-American Girls Softball League—P.K.’s idea to fill stadiums during World War II.

Shep and Dorothy grew apart in the forties, partly from the strain of their elder son’s metal illness. Dorothy chose to relocate with her younger son to Northern California, where, unfortunately for us, she put commercial work aside forever. Instead, she focused on fine art and taking care of her family. In her late personal work, Dorothy explored abstraction with hard-edged paintings and collage using limited color palettes on white grounds that are reminiscent for me of those of Kazimir Malevich. The Suprematist artists liked to create gradients with their paintbrushes, and perhaps that drew her to their work.

In 1962, the two great designers—Dorothy was fifty-six, and Otis was sixty-eight—reunited, set up house together, and traveled once more to New York City. I was so moved by Hathaway and Nadel’s choice to close Dorothy and Otis’s story with a spread showing two blue-tinted, large format, Polaroid-type candid photographs—one of Dorothy shot by Shep, the other of Shep shot by Dorothy. They are approaching the harbor by boat, each foregrounding a midcentury Manhattan skyline. Their poses in relation to the rail of the boat and to the city seem to suggest that each found separate paths in both life and in work and honored the other for it.

Charlotte Strick is art director of The Paris Review.

November 14, 2014

Staff Picks: Megg, Mogg, Maxim Maksimich

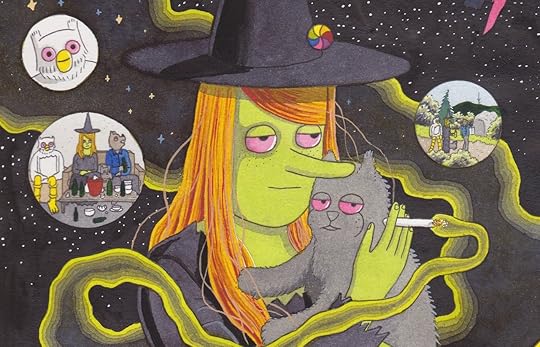

From the cover of Megahex.

Last month, Simon Hanselmann’s comic book Megahex entered the New York Times Graphic Books best-seller list at number 8, both above and below volumes by Neil Gaiman. No small feat, especially when you consider the Times’ droll description of the book: “Meet Megg. She’s a witch and has a black cat named Mogg. She is also depressed and addicted to drugs.” It’s not inaccurate, but it sure misses the point. Megg and Mogg are druggy reprobates who tease and torture their roommate, Owl, who is himself a rather unsavory fellow, but Megg’s depression isn’t your garden-variety Prozac episode. She’s so invariably and subtly disconsolate and experiences such disturbing mood swings that it’s impossible not to feel at least a tinge of that heavy sadness. And because the book is funny, too—they smoke lots of pot—her depression seems that much more real. —Nicole Rudick

In recent weeks—when I haven’t been poring over Greif’s Crisis of Man—I’ve been unwinding with classic short stories: Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin and Randall Jarrell’s Book of Stories, in which the great poet and critic presented an idiosyncratic mix of all-time favorites, from fairy tales, to the Russian masters, to poems by Frost and Brecht. —Lorin Stein

Most writers are failures, and C. D. Rose knows that. His Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure is a compendium of fictitious authors, all of whom are spectacularly unsuccessful. Spend an hour with it—ideally not an sober hour—for a bracing, mordant reminder of why almost nothing is really worth bothering with. My personal favorite fake failures: Maxim Maksimich (“he died in 1912, impaled by an icicle, a casualty of the thaw for which he had waited so long”), Belmont Rossiter (“he challenged Dickens to a duel and allegedly tried to poison Wilkie Collins … He told George Eliot she looked like a horse”), and Elise La Rue (“she wrote longhand, naked, voluptuously, lying on her divan, usually covered in the fur of a snow leopard which she claimed she had herself skinned … accompanied by her favorite cocktail of schnapps and Dubonnet”). —Dan Piepenbring

I hate to admit this, but I found myself mesmerized by Kickended, a new archive of Kickstarter’s zero-dollar-pledged campaigns created by Silvio Lorusso with the help of Kickspy’s data analysis. Click on the Random Campaign button, and you’ll bring an array of crowdfunding flops to light, from a kid’s book on Occupy Wall Street to the restoration of The Commodores’ 1947 cargo van. It’s easy to poke fun at these projects—especially with campaigns like this and this and this. But it’s more than just an exercise in schadenfreude; it’s a fascinating look at why certain projects succeed and others don’t. Why is there a place in this world for fruit-themed plush toys but not The Amazing Spider-Pig piggy bank? A tool to shotgun beer better but not a bra that doubles as a pocket? Is one better than the other, or is it simply the way the project is presented? Maybe it’s the fact that no one wants to be the first to donate to these “abstract ideas.” Everyone knows you always put a few dollars out of your own pocket into the tip jar. —Justin Alvarez

The Soul of Wit

Photo: Carpe Donut NYC

While contemplating the purchase of a hot-cider doughnut at the aptly named Carpe Donut truck, one finds oneself thinking about food-truck names. Many have; it is one of the consolations of modernity that we live in the golden age of food-truck nomenclature. Or at least the first age.

Anyone who has worked in a business district or watched an episode of Street Eats knows it’s not enough to have a truck and a grill: your name should ideally be gimmicky, fun, and filled with attitude, to underlie the anarchic spirit of the whole enterprise. Sexual innuendo is of course desirable. Puns are a plus. In the words of an academic with whom I once spent a tedious dinner, “Language informs consciousness: we know this.”

But did you know that there is a f? Of course there is. (I have no knack for it; my key words—scampering, spinster, maple—were apparently not sufficiently cheeky, even after I added sullen to the mix for extra attitude.) But then, I didn’t really need it; I already have the perfect name. Ogden Nosh. We’ll sell franks, but of course, they’ll be called Doggerels. The way some fast-food chains give their customers discreet Bible verses on the bottoms of cups, we’ll force-feed our patrons nonsense verses. And, naturally, on the side of the truck will be written the following: “A door is what a dog is perpetually on the wrong side of.”

Enlarge and Linger

On William Gass’s In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.

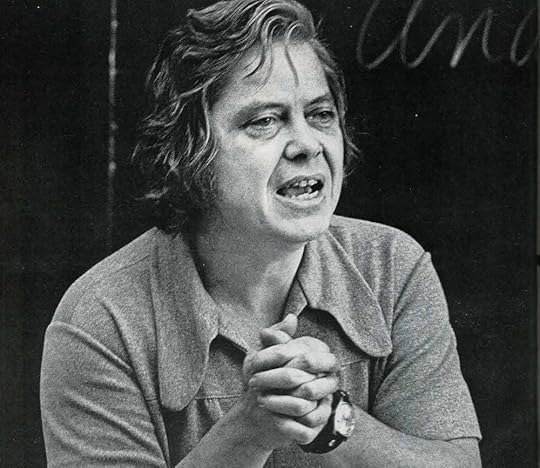

William Gass teaching at Washington University, 1974. Photo: Washington University Magazine

In the heart of the heart of William Gass’s In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, deep inside the title story, the narrator contemplates his cat, Mr. Tick: “You are a cat—you cannot understand—you are a cat so easily.” The confident Mr. Tick, unlike the narrator, does not worry over his mortality or think about the burden of self-consciousness. He does not care that the past is past. He does not fear possibility or imagine himself as anything other than the cat he is. Mr. Tick spends his time murdering birds and walking across rooftops. Content just to be alive, he moves elegantly, “his long tail rhyming with his paws,” leaving our forlorn narrator to fend off loneliness on his own, with the only weapon he has at his disposal: words.

Words are free, there for the taking, and William Gass makes sure we are aware of their infinite potential. Words can be used to command, to describe, to denigrate. They can be strung into sentences and bellowed in a song “in such a way that from a distance it will seem a harmony, a Strindberg play, a friendship ring.” We understand nuance and learn how to prepare for consequence with the help of words. We can make beautiful things with words. Those inclined can dare to treat the medium of language as an inexhaustible source of art.

Art is the business of serious writers, Gass insists. A brilliant essayist as well as one of this nation’s most important novelists, he argues in his essay “Philosophy and the Form of Fiction” that the task for a serious writer is twofold: “He must show or exhibit his world, and to do this he must actually make something, not merely describe something that might be made.” In his emphasis on making, Gass, who turned ninety this year, is proposing that the meaning generated by a work of fiction goes beyond its mimetic familiarity. The purpose of an imaginative narrative isn’t to confirm what we think we already know about reality; rather, it offers “a record of the choices, inadvertent or deliberate, the author has made from all the possibilities of language.” a fictional cat may reflect qualities of a real cat, but it is better appreciated as a product of the author’s agile mind.

*

In the Heart of the Heart of the Country was first published in 1968; it comprises stories that began to appear in periodicals in the late fifties. For Gass and his generation at that moment, modernism was such a gargantuan precursor that it threatened to obscure the work that followed. Whether they considered literary modernism a failed experiment, characterized by H. G. Wells as a “monstrous egotism of artistry,” or a grand success that expresses, in Virginia Woolf’s estimate, “the quick of the mind,” novelists beginning their careers in the fifties and sixties necessarily had to position themselves in response to the dramatic shape shifting that had just occurred in their genre.

Looking back over this heady period in American literary culture, John Gardner would claim that no one writing at that moment “was willing to live by the old, righteous rules.” Fiction, like all art, was supposed to be free from the shackles of rules. Ezra Pound’s call to “make it new” (a slogan that Pound tellingly recycled from Chinese historical sources) continued to reverberate as the defining challenge.

Gardner recognized the need to give these adventurous new writers a venue and in 1960 cofounded the literary journal MSS, based in California. While he was collecting material to publish in the first volume, a story called “The Pedersen Kid,” by a young writer named William Gass, came to his attention. A fellow editor told Gardner that the story had been rejected at another journal because it had “questionable language; doubts had been expressed about meaning and point of view.” We know from Gass that he had been sending out the story for seven or eight years before it landed on Gardner’s desk. Gardner jumped at the opportunity to publish it.

In “The Pedersen Kid”—the lead story in In the Heart of the Heart of the Country—Gass has created a narrative that, with its disruptions and immersions, is reminiscent of Quentin’s chapter in The Sound and the Fury. Like Faulkner, Gass does more than depict a boy’s experiences; he offers a full enactment of a boy’s confusion. As Jorge struggles to assess the danger of his predicament near the end of the story, even the print takes on dramatic shape in an expression of fear: “He’s even come round maybe. Oh no jesus please. Round.” At the same time, Gass conveys the physical impact of the setting with unrivaled intensity, offering, through Jorge’s perception, a Midwestern landscape where snow is “as blue as the sky,” stars are “flakes being born that will not fall,” and larks in summer “winked with their tails taking off.”

Devoted as he is to artistic excellence, Gass has never been cowed by the bold ambitions of the modernists. Just the opposite. In his essays, he pays tribute to writers he associates with what he calls “a permanent avant-garde”—Gertrude Stein, Henry James, Kafka, Beckett, Joyce. Gass’s own essential fiction, written over the past half century, offers us a strikingly varied array of forms, all enriched with wit, intense emotion, and provocation, all full of the promise of discovery. He doesn’t mind when a writer’s intelligence is on display, especially since he values the intelligence of a perceptive reader. He reminds us that art is a proven human glory, and that literature shares with all great art the potential to expand our awareness.

*

In the Heart of the Heart of the Country reaches across two great expanses: the harsh, flat exterior landscape of the Midwest, and the mysterious interior landscape of human consciousness. Both landscapes hide secrets. Beware the salesman Pearson, in Gass’s story “Icicles,” who twists his magazine into a roll and with a whack asserts his certainty: “It’s so clear. It’s so easy. It’s so clean.” In these fictions, Gass shows us that certainty is an elusive prey. Snowdrifts cover evidence of a terrible crime. Typewriter-ribbon tins hide a housewife’s obsession. A man goes into his house, closes his door, and closes his eyes—“there’s simply no way of knowing how lonely and empty he is … here in the heart of the country.”

We travel with Gass through this collection toward a center that beckons, the heart within the heartland. “This Midwest,” says the narrator of the title story, “a dissonance of parts and people, we are a consonance of towns. Like a man grown fat in everything but heart, we overlabor; our outlook never really urban, never rural either, we enlarge and linger at the same time, as Alice both changed and remained in her story.” For Gass—born in North Dakota, raised in Ohio, and rooted for the past several decades in St. Louis—the American Midwest is home. The region, with all its consonance and dissonance, enriches his literary explorations. The scenery and weather, the noises of its farms and neighborhoods, the conflicts and longings of its people are vividly rendered. But Gass’s fictional Midwest is also infused with mystery—“epiphanous,” he asserts, yet still “an enigma.”

The stories invite us to follow the author’s map and focus our attention. “So I have sailed the sea and come … / to B … / a small town fastened to a field in Indiana.” It may seem a barren land from afar, yet up close we see it is teeming with singular characters. Meet the formidable Aunt Pet, who will raise the knob of her walking stick to the level of your eyes. There’s Big Hans, who drops the frozen Pedersen kid on the table, on top of biscuit dough. Rolling and raking, spinning and clipping, waging war against the weeds is Mrs. Mean—that’s not her real name, but it serves her fine. A gaggle of children run through this book: the boy known only as the Pedersen kid, Jorge, Ames, Nancy, Toll, Tim, Cheryl Pipes, Paula Frosty. And sauntering through the neighborhood goes that dignified cat with his perfect name, Mr. Tick.

Words are names we attach to things to create definition. In Gass’s hands, the outline of meaning is filled in and expanded with comparisons, contrasts, implications, confessions, rebuttals, questions, arguments, derision, and repetition. Words to watch for in these stories include snow (it’s beautiful, deadly, boring, and defiant), inside (where characters go for shelter from the cold, where they hide, and where they can’t escape themselves), imagination (we learn from the housewife in “Order of Insects” how easy it is to lose control of it), world (jostle it a little, and the L comes out: “The world—how grand, how monumental, grave and deadly, that word is”), and, of course, heart.

Added together into sentences and paragraphs, words are the signs that provide a route toward truth. We tunnel through snowdrifts and head inside, seeking to discover what lies in the hearts of these characters. It’s not, as the salesman Pearson pretends, clear, easy, or clean. Nor should it be, not with so much at stake. Gass gives us the opportunity to learn more than we thought it possible to know about his subjects, and to enjoy the pleasure that comes from a deepening of understanding. We imagine what it’s like to inhabit other selves. Through them, we may begin to grasp the beauty and enormity of the world this writer has created.

A version of this essay appears as the introduction to the NYRB Classics reissue of In the Heart of the Heart of the Country , published earlier this month. © 2014, reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Joanna Scott’s most recent novel is De Potter’s Grand Tour. Her other books include the novels Arrogance, The Manikin, and Follow Me, and the story collections Various Antidotes and Everybody Loves Somebody.

Sketches from an Artificial Mind, and Other News

Not a fair fight: five robots sketch one man. Photo via Beautiful/Decay

A new collection of stories from the tenth-century Arab world is agreeably unhinged, particularly when it comes to sex. In “The Story of the Forty Girls and What Happened to Them with the Prince,” for instance, “a Persian prince stumbles across an enchanted castle run by a sorceress and her troop of warlike female cousins. Divested of their armor, the girls prove to be ‘more beautiful than the houris of Paradise,’ and queue up to enjoy his favors (naturally they are all virgins). Finally the sorceress offers herself to him, forbidding the prince—who is impressively not yet exhausted—from approaching any of the others again on pain of being imprisoned, tortured and loaded with iron chains; conditions to which he cheerfully agrees. That’s forty couplings, and then some, since the sorceress, having miraculously regained her virginity, presents herself for a second deflowering.”

If you’d prefer to keep things chaste, look to love in the time of telegraphy. The nineteenth century saw a vibrant subgenre of the romance in which telegraph operators flirted across the wires. “There’s something incredibly modern about these amateur stories and the way they handle technology, the influence of corporations, gender, and love in the time of hyperconnection.”

A history of the New York Times Style section and its uncanny ability to court controversy: “For decades, many of us have used ‘reading the New York Times’ as a kind of performance, a shorthand to convey our seriousness or sophistication or social cachet, or yes, even our affluence. To read the Times daily, we think, is to signify that one is in this world, but not of We imagine ourselves the world’s observers, its makers, or even its collective conscience. We want to believe we are reading from far above the fray of Juicy Couture, or Botox, or any of a hundred other manifestations of rank consumerism, vanity and anxiety. The section instead is a jarring, insistent reminder of the folly of this fantasy. Styles, we are you.”

Novelists and musicians earn royalties on their work—visual artists don’t, meaning they receive nothing from multimillion-dollar deals involving their art. Art Royalties Too, a new bill making its way through the congressional meat grinder, will try to change that, but no one knows if it will pass. “Intellectual property is a very unusual area in Congress. As a general rule, you cannot predict where someone is going to be on an issue like this or on music licensing by knowing that he’s a Democrat or Republican.”

I wrote earlier this week about a robot that could give you the creepy sensation that someone is right behind you. But the world has no shortage of terrifying robots, and so now I give you this: Paul-IX, a robot who can sketch with more talent and accuracy than most humans. (If this robot teamed up with the other, it could get some great sketches of you looking creeped out.)

November 13, 2014

The Look of the Sound of the Seventies

Photo: Audiophile USA

Harry Pearson, the founder of The Absolute Sound, died last week at seventy-seven, the New York Times reports. From its inception in 1972, The Absolute Sound was (and remains) an audiophile’s dream magazine. As the Times describes it,

Mr. Pearson laid the foundations of a philosophy and vocabulary that helped give rise to a worldwide subculture of high-end audiophiles. He wrote about recorded music with the conviction and nuance that food critics brought to haute cuisine, assessing qualities of depth, naturalness and “three-dimensionality” in the sound made by some stereo components and not others ... When all those intangibles came together in the right way, he said, they produced “absolute sound,” which he defined as “the sound of actual acoustic instruments playing in a real space.”

And it must be said: The Absolute Sound had incredible cover art and design, especially in its first years. Just look at those covers!

“Mr. Pearson initially refused to accept advertising but relented after a few years, though vowing not to soften his analysis,” the Times notes. And sure enough, the back of an early issue I found carries maybe the finest, purest statement of revenue philosophy I’ve ever seen from a magazine:

WARNING: Do not lend your copy of The Absolute Sound to friends. You endanger the continued existence of the magazine by so doing. The Absolute Sound exists entirely on subscription revenues. Freeloaders decrease our revenues, and not surprisingly our incentive. If you really like the magazine and want it to survive you will needle your friends into subscribing.

Kudos to Pearson for his clarity of vision—would that his revenue model would’ve panned out. Here, in remembrance, are three of the best seventies-era Absolute Sound covers I could find:

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers