The Paris Review's Blog, page 651

October 23, 2014

Above the Ice

Grief and adventure on the path to the North Pole.

François-Auguste Biard, Magdalenefjorden, 1840.

For two weeks in the summer of 2013, I traveled around the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard as part of the Arctic Circle Residency, proceeding up the west coast of the main island, Spitsbergen, and making landfall at tiny settlements and untrammeled beaches at the edge of the known world. At one point, our course took us into a small fjord where we sailed past an abandoned mining town called Blomstrandhalvoya; a research station, Ny-Ålesund, on the opposite shore; and, farther in, two massive glaciers, Kongsvegend and Kronebreen, twin ice masses sliding slowly into the fjord.

The glaciers hug a promontory butte that stands in defiance to these ice sheets, though they are both slowly wearing it away. In a struggle imperceptible to human eyes, the glaciers grind relentlessly against the rock face, carving their inexorable history into its striated face. They could win against this rock, wearing it down over eons into a plain or even a valley, but instead they’re ceding the battle, retreating backward. At some point in the future the promontory will be an island, as the glaciers recede and allow water to spill in behind them.

The sound you hear when you put ice cubes into warm (but not hot) water—that subtle but quick crackling—is the sound all around you in the summer fjords near glaciers. There is ice everywhere in the water, the size of your fist and the size of small islands, and because the water is only a few degrees above freezing, the ice cracks slowly, abundantly. It takes a moment to understand what you’re hearing, because it’s so constant and so low in the air—this soft crackle, like static over a radio.

Next to the noise, there is the wind. Strong, persistent, a wall of bitter blue. Constant: no slack, no gusts, as if from an electric fan. It is utterly cold and utterly fierce. You gaze into the white at the edge of the glacier that gives way slowly to its interior blues, blues of a depth for which there is no word, buffeted by the wind, which streams steadily and directly into you.

Gretel Ehrlich calls glaciers archivists because of their ability to preserve so much history. “Ice cores are time machines,” she writes:

Snow piles up, compresses, and becomes firm, then ice mounds up into glaciers; oxygen bubbles are trapped in the ice, providing samples of ancient atmosphere, of how much carbon dioxide and methane is held within. Records of past temperatures and levels of atmosphere gases from before industrialization are compared with those after—a mere 150 years.

As the great Kongsvegend and Kronebreen slide quietly back into the land, this past record will be gradually loosed from them. “Trapped carbon dioxide is like grief,” Ehrlich concludes, “it has to go somewhere.” All around us, it was going everywhere. The moment when a piece of glacier breaks off and falls into the sea is called calving, and everywhere the calves of Kronebreen and Kongsvegend drifted by, far from silent with the crackling static of the ice. Calving makes a noise exactly like distant thunder or the fall of centuries-old trees. Sometimes you catch the moment of calving, realizing how seemingly small a piece can make so great a sound. Sometimes you miss it, seeing the ice only as it drifts free in the water. And sometimes you hear it and look and see no trace of it whatsoever: the rumbling comes from deep somewhere in the glacier. One unnamed sailor described it more than a century ago:

The song of the sea ice is a very peculiar one, and can scarcely be described so as to convey any clear idea of its nature. It is not loud, yet it can be heard to a great distance. It is neither a surge, nor a swash, but a kind of slow, crashing, groaning, shrieking sound, in which sharp silvery tinkling mingle with the low, thunderous undertone of a rushing tempest. It impresses one with the idea of nearness and distance at the same time and also that of immense forces in conflict. When this confused fantasia is heard from afar through the stillness of an Arctic night the effect is strangely weird and almost solemn, as if it were the distant hum of an active, living world breaking across the boundaries of silence, solitude and death.

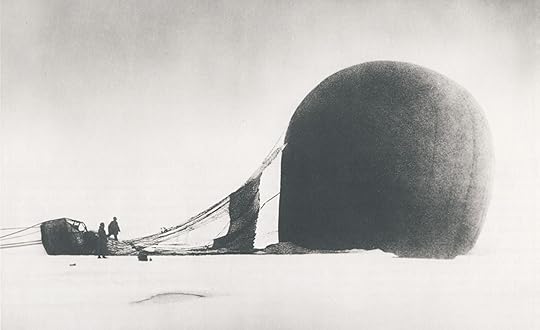

I found this quote in Alec Wilkinson’s The Ice Balloon, a recent history of Salomon August Andrée and his attempt to reach the North Pole in his helium balloon, the Örnen, in 1897. After so many polar expeditions had been bedeviled by the shifting, merciless pack ice, ice that crushed ships and proved an unstable terrain for overland crossings, Andrée devised a plan to sail over the ice in a balloon, using trailing lines of guide rope dragged along the ice as a crude kind of rudder. He believed he could reach the North Pole from Svalbard in a matter of hours. He set out from a northern harbor in Svalbard, Virgohamna, in the company of two men, Knut Fraenkel and Nils Strindberg, a photographer. Calamity beset them almost immediately: two of the guide ropes were tangled and lost during launch and the balloon floundered for nearly three hundred miles before crash landing on the ice. On foot, Andrée and his companions spent two months working their way south, hoping to make it back to civilization, before dying on the tiny island, Kitvøya, just east of Svalbard. In 1930 their remains were finally discovered, along with rolls of Strindberg’s undeveloped film.

The most iconic of these is a photo Strindberg took soon after the Örnen had first crashed on the ice; from a distance of twenty or thirty feet, Strindberg captured Andrée and Fraenkel standing beside the half-deflated balloon, their poses indicating neither despair nor horror so much as idle curiosity, as though they were witnessing the thing on display at a world’s fair. Perhaps they still believed their voyage overland would be successful, that they will reach the stores of provisions they’d stowed at Svalbard and nearby Franz Josef Land. Perhaps they did not know yet that they were doomed.

The crash of the Örnen.

I return to that image often, an image of deflation in the fullest sense of the word. Deflate, from the Latin flare, “to blow.” Even if they do not realize it yet, Andrée and his companions are blown out, exhaled. The image now encapsulates a whole history of nineteenth-century hubris and the long-held belief that nature is an easy conquest, a thing to be bested through scientific ingenuity and will.

* * *

Trapped grief is like carbon dioxide; it has to go somewhere. Strindberg’s fiancée, Anna Charlier, never got over his death. She waited for thirteen years after his disappearance in 1897 before remarrying, but in her own way she stayed true to him even then. She was still alive in 1930 when his remains were found and returned to Sweden for reburial, the grief inside her slowly thawing. When she did die, in 1947, she had her husband cremate her body and her heart separately and bury the remains of her heart alongside Strindberg’s, her first and only love.

When I was in Svalbard, grief never felt very far from the surface—nor did the bodies of the dead themselves, which linger rather than decompose. The permafrost is so thick that you can’t be buried very deep; the cold preserves your remains for decades, if not centuries. Residents in the main settlement of Longyearbyen must make arrangements to have their bodies shipped home when they die; in the tiny graveyard of Longyearbyen, there are barely thirty graves, all but three or four with standard white crosses and a uniform plaque, and nearly all dating to before 1940.

Photo: Godot13, via Wikimedia Commons

The markers carry no information but names and dates, and yet they offer glimpses of a story. In some cases, one finds the same date of death in a succession of markers—Konrad Kristofferson, age thirty-seven, Helge Nilsen, age twenty-seven, Nils J. Krog, age thirty-two, Karl Johan Enkvist, age thirty-four, all dead January 3, 1920—a calamity that’s never explained.

In 1918, a succession of Longyearbyen’s residents were wiped out in a single week. Ole Kristofferson, October 1; Magnus Gabrielsen, October 2; Tormod Albrightsen and Hans Hansen, October 3; Johan Bjerk and William Henry Richardson, October 4; Kristina Hansen, October 7. All of them, I later learned, died of the Spanish flu, which must have torn through the tiny mining community that bitter autumn. Because they were buried in permafrost, and thus subject to almost no decay, contemporary researchers thought their remains might still contain frozen specimens of the virus that killed them; hoping to isolate the original influenza strain, scientists exhumed their bodies a few years ago. They were unsuccessful, and while an epidemiologist might regard that as a setback, most of the people I spoke with sounded relieved to learn the scheme didn’t work, as though they’d been afraid they would somehow resurrect the virus.

Svalbard’s pristine wilderness is nearly devoid of human life and would thus seem impervious to tragedy and grief, but stories like these kept coming to me, and kept alive my sense that beneath the topmost layer of ice there were grief and loss waiting. One of our guides, Åshild, told me of a haunted house near Longyearbyen. As I recall Åshild’s story now, the building was a research station in the early 1910s. An expedition was stranded at some point in the ice off the northwest shore, and a group of eleven sailors set off south in rowboats to find help. They made it to this house, where they overwintered. In the spring, a would-be rescue party found two graves outside, but they had hope when they thought they saw a man sitting inside the house at a table. But the man was dead, as were all the others—in natural positions, some in bed, some in chairs. They smelled terrible, but were mostly preserved by the cold. The building is still there, and still in use, though now it’s haunted by these eleven dead sailors. It’s still in operation, it turns out, because it was built above the tree line, where wood is so scarce that not even haunted houses are torn down.

* * *

Launching a weather balloon at Ny-Ålesund.

After gliding past Kongsvegend and Kronebreen, we backtracked and moored at Ny-Ålesund, the research station near the mouth of the fjord. It boasts an international cadre of scientists, a small museum, and the world’s northernmost post office—one of the few inhabited settlements in the entire archipelago of Svalbard. At Ny-Ålesund, they launch weather balloons, helium balloons about five feet in diameter, to which are attached Styrofoam coolers full of instruments to track ozone quality, barometric pressure, weather, location, et cetera. The balloons rise about five meters per second, ascending about thirty-five kilometers into the atmosphere before bursting—at which point the equipment stops working and the entire apparatus falls uselessly back to earth. There is a bounty for any that are returned to Ny-Ålesund, but none have ever found their way back.

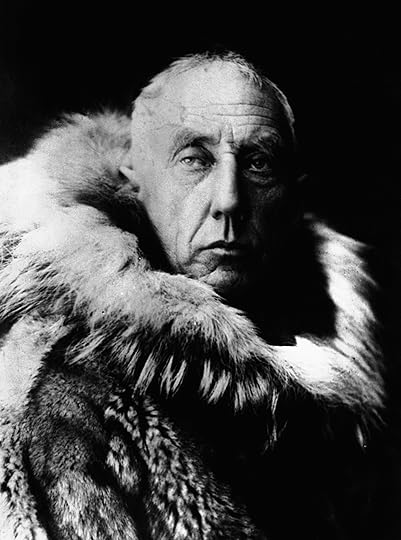

Salomon Andrée’s legacy is an important part of Svalbard, but here he is eclipsed by another figure, Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian who was far more successful. In the 1920s, Amundsen used Ny-Ålesund as a launching point for two attempts to reach the North Pole by air. “The future of Polar exploration lies in the air,” Amundsen wrote in his autobiography, “and I am cheeky enough to claim that honour for myself as I was the first serious polar researcher who realized this and who practically demonstrated this method’s potential.” Always a canny self-promoter, Amundsen had no problem largely erasing the earlier tradition of aerial polar exploration, though it is true that he was perhaps the first to seriously study the problem rather than simply hurling himself into the polar winds. Before his South Pole expedition, Amundsen spent months calculating how much weight a sled dog could carry, how many provisions each man would need, how many miles a day could be sensibly covered—mathematically determining the maximum efficiency. He stands out against a history of noble but largely romantic expeditions in which brute determination was expected to carry the day.

Roald Amundsen

By the time he came to Ny-Ålesund, he was a few months shy of fifty and had already been the first to traverse the Northwest Passage and the first to reach the South Pole, beating Scott by weeks. The South Pole was a triumph, and what perhaps most will remember him for, but Amundsen was Norwegian: his heart lay in the North. By then Amundsen had begun to refer to himself as the Norwegian version of the Flying Dutchman, “doomed to lifelong travels in the Arctic Ocean.”

His first attempt to take the North Pole by air came in the spring of 1925, via two seaplanes. The journey was financed by his friend and fellow explorer Lincoln Ellsworth, and the two left on May 21, making it eight hours before being forced by weather to land at 83.43 degrees north. The two planes became separated, and it took almost a month before they were able to take off again and return home.

This failure was quickly eclipsed by the successful second journey, undertaken not in planes but in a massive dirigible, the Norge, piloted by the Italian engineer Umberto Nobile. The expedition left almost exactly a year after the first, on May 12, 1926, and crossed the pole at 1:30 A.M. on May 13, landing ultimately at Teller, Alaska.

A journalist who watched the Norge’s launch wrote, “The Arctic smiles now, but behind the silent hills lies death.” At Ny-Ålesund you can buy T-shirts with an Amundsen quote: “Adventure is the result of bad planning.” He’s held up as an example of success, of meticulous planning, grit, and achievement. Not to diminish the heroism of men like him, but I sometimes question the value of these successes. Shortly before leaving for Svalbard, I came across this quote in Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, which I returned to often throughout that trip:

There have happened, though rarely, in geographical space, journeys taken northward on very blue, fire-blue seas, chilled, crowded by floes, to the final walls of ice. Our judgment lapsed, fatally: we paid more attention to the Pearys and Nansens who returned—and worse, we named what they did “success,” though they failed. We only wept for Sir John Franklin and Salomon Andrée: mourned their cairns and bones, and missed among the poor frozen rubbish the announcements of their victory. By the time we had the technology to make such voyages easy, we had long worded over all ability to know victory or defeat. What did Andrée find in the polar silence: what should we have heard?

Would Amundsen, I wondered, have crossed by balloon if Andrée had not attempted it first? Was Amundsen doing anything but redeeming an earlier failure? Does his story exist as anything other than a shadow of that earlier failure? It’s maybe not the first to succeed that matters, but the first one to attempt—in whose imagination all subsequent attempts, failures and successes, are contained.

Would Amundsen, I wondered, have crossed by balloon if Andrée had not attempted it first? Was Amundsen doing anything but redeeming an earlier failure? Does his story exist as anything other than a shadow of that earlier failure? It’s maybe not the first to succeed that matters, but the first one to attempt—in whose imagination all subsequent attempts, failures and successes, are contained.

As we left Ny-Ålesund, others perhaps carried with them that glorious fling of the weather balloon into the sky, a triumphant gesture to hedge against the doom and apocalypse that were gradually being predicted by its measurements. I was fixated on an earlier moment, as the balloon was being inflated and readied for its one-way journey: it had lain half filled, looking just like Andrée’s Örnen crashed on the ice.

Colin Dickey is the author of Afterlives of the Saints: Stories from the Ends of Faith and Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius.

Another Bartleby, and Other News

Constantin Meunier, Pays noire (Black Country—Borinage), ca. 1893, oil on canvas.

“On a winter’s day in 1482 a scholar had an embarrassing disaster, leaving a blood-red blot of ink on the pristine page of a valuable book. He then compounded his crime by confessing, adding a note in the same red ink still legible after 532 years. On the desecrated page of the Historiae Romanae Decades, printed in Venice in 1470, he wrote: ‘Ita macula’—this stain—‘I stupidly made on the first of December 1482.’ ”

On George Whitman, the eccentric founder of Shakespeare and Company: “He could be welcoming. He could be gruff. He could be charismatic. He could be aloof … This was, after all, a man who on occasion expressed himself by throwing books at people, sometimes affectionately, sometimes less so—a love-hate gesture, or so it sounds, not unlike Ignatz Mouse hurling bricks at an eternally besotted Krazy Kat.”

Novelists, here is your picaresque, contemporary Bartleby: an Italian coal miner who shirked work for thirty-five years and is now collecting his pension. “I invented everything—amnesia, pains, hemorrhoids, I used to lurch around as if I was drunk. I bumped my thumb on a wall and obviously you can’t work with a swollen thumb … Other times I would rub coal dust into my eyes. I just didn’t like the work—being a miner was not the job for me.”

Let’s trade fossil casts: “In the first part of the twentieth century, casts of fossil specimens were key to paleo sciences. Because actual fossils were too valuable and rare to ship to international researchers, casts of fossils circulated in their stead … Paleoanthropologists would offer to trade casts of ‘their’ fossils to other researchers in different areas of the world, who had different looking specimens—the casts became a social currency.”

In praise of reading plays: “A great published script makes you understand what the play is, at its heart. Not just what a certain production was like, though it also ought to do a good job of that. It makes you understand how the play feels as a living work of art—how it sounds and behaves inside your head, a mental effort that matters more in reading a play than in reading any other kind of literature.”

October 22, 2014

The Brain of the City

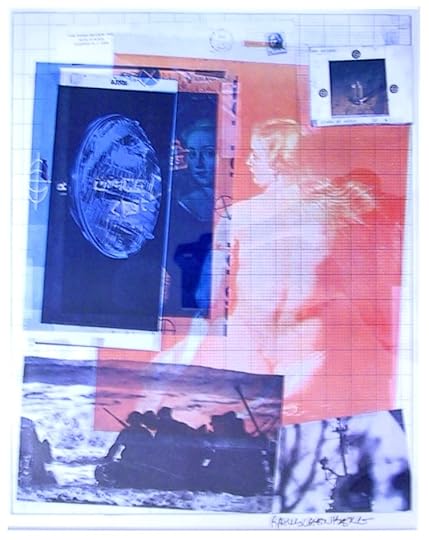

Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, 1965, lithograph, 25" x 21"

I once heard Jasper Johns say that Rauschenberg was the man who in this century had invented the most since Picasso. What he invented above all was, I think, a pictorial surface that let the world in again. Not the world of the Renaissance man who looked for his weather clues out of the window; but the world of men who turn knobs to hear a taped message ... electronically transmitted from some windowless booth. Rauschenberg’s picture plane is for the consciousness immersed in the brain of the city.

—Leo Steinberg, “Reflections on the State of Criticism,” Artforum, March 1972

Since 1964 The Paris Review has commissioned a series of prints and posters by major contemporary artists. Contributing artists have included Andy Warhol, Helen Frankenthaler, Louise Bourgeois, Ed Ruscha, and William Bailey. Each print is published in an edition of sixty to two hundred, most of them signed and numbered by the artist. All have been made especially and exclusively for The Paris Review. Many are still available for purchase. Proceeds go to The Paris Review Foundation, established in 2000 to support The Paris Review.

This print is by Robert Rauschenberg, who died in 2008; he would be eighty-nine today. His print came in an edition of 150 that has, alas, sold out, but there are many others available here.

Material Objects

Lessons from Rare Book School.

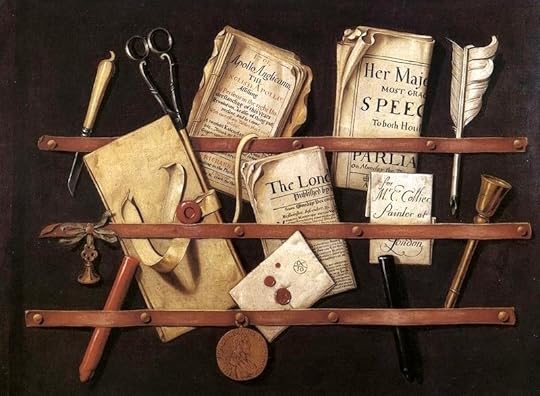

Edward Collier, Trompe l'Oeil of Newspapers, Letters and Writing Implements on a Wooden Board, 1699.

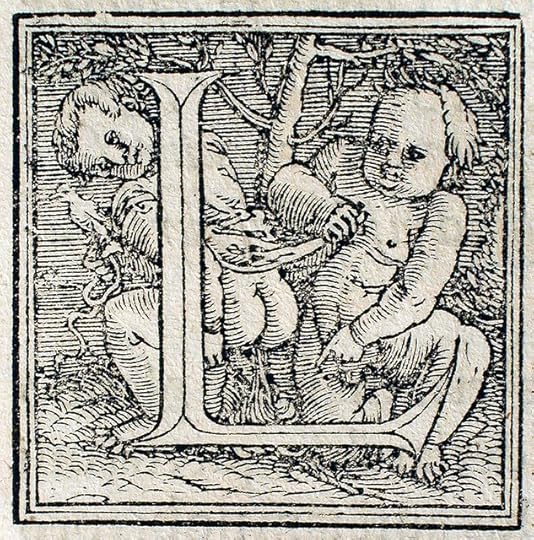

Four stories underneath the stately Georgian campus of the University of Virginia, I was with a group of rare-book experts scrutinizing a five-hundred-year-old Italian woodcut of two chubby infants. They framed a capital letter L. One, with a look of insouciant concentration, was thrusting his butt over the downslope of the L to defecate on it.

“The woodcut accompanies Andreas Vesalius’s discourse on the muscles of excretion,” Roger Gaskell, a rare-book dealer based in Cambridgeshire, told the group. It turns out that Vesalius, the Renaissance physician remembered today as the father of modern anatomy, had an intensely strained relationship with his publishers. “This initial letter differs from the others in the book—despite the fact that the printing house had a perfectly good L already cut,” Gaskell said. “So I rather suspect this shitting putti was a message to his publisher.”

Over a coffee break, the members of Gaskell’s seminar mingled with three others led by such luminaries as Mark Dimunation, the chief of the rare-book division at the Library of Congress. They were gathered in a warren of windowless basement rooms for an annual rite of passage in the world of antiquarian texts: Rare Book School.

The classes marked the penultimate week of a summer-long series of intensive courses that delve into every aspect of books as material objects. The school’s leader, Michael F. Suarez, S.J., a charismatic Jesuit and professor of book history, has been cultivating a new field that he calls “critical bibliography.” Precisely what those words meant was a subject for debate among the participants (“The study of the physical characteristics of books and the process of bookmaking” is the definition the Society of American Archivists gives) but they all agreed that Suarez was a force to be reckoned with. It’s like a cult was a commonly heard phrase at the School. As one participant put it, “Finally, I found a cult I want to be a part of!”

Over drinks at the student bars lining the approach to Thomas Jefferson’s Rotunda, seminar participants traded book-nerd credentials. “My friend cut out all the endnotes from Infinite Jest and made them into footnotes by gluing them onto the bottoms of the pages,” confided Courtney Roby, an assistant professor of classics at Cornell who studies Greco-Roman technology. Aaron Pratt, an excitable Yale English Ph.D. student and rare-book dealer, was enthusing about the merits of another form of collectible media. Pratt owns more than a thousand VHS tapes—“mainly low-budget horror films between 1979 and 1983”—and was still feeling the afterglow of a recent triumph. “I finally convinced the Sterling Memorial Library to start buying up first editions of early VHS tapes.”

The Portuguese have an untranslatable word for the ineffable nostalgia of something that has passed away and perhaps never was: saudade. At Rare Book School, saudade for the world of print was in the air. But the presiding emotion was joy, shaded with a kind of reverence. The next afternoon, Gaskell’s class marveled over a unique copy of the Encyclopédie in which Diderot had handwritten his own line edits. A UVA curator speculated that the gold-edged volume, recovered from the Nazis by American GIs during World War II, may have been Diderot’s presentation copy to Catherine the Great, but no one was sure. It was an historical epic in miniature, a mystery bound up between gilt leather covers.

Also in tow at Rare Book School was Lee Powell, a video reporter from the Washington Post with a thoughtful mien. He said he’d been hired by the Post the year before, part of a shift away from traditional print and toward video reporting engineered by his new boss, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. Powell watched the proceedings with a look of quiet attentiveness, a camera perched on his shoulder. It was his final hour of shooting, and he was trying to construct a narrative of the film-to-be in his head. “I like to structure it with a beginning, middle, and end,” he said. “But I haven’t figured this one out yet. It often comes to me when I’m in the car, driving back from an assignment.” When I pressed him about his final shot, he hesitated and gave a wry smile. “I’m thinking about ending it with a closing book.”

“What a glut of books!” Richard Burton complained in 1621: “We are oppressed with them, our eyes ache with reading, our fingers with turning.” What will be lost, though—what new oppressions will come—when we stop turning pages and start swiping sapphire? Rare Book School, at least, isn’t going anywhere—they’re currently offering fellowships to train a new vanguard of critical bibliographers, starting next summer.

Andreas Vesalius’s L.

Benjamin Breen is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin and the editor-in-chief of The Appendix, a new journal of narrative and experimental history. His writings have appeared in Aeon, The Atlantic, The Public Domain Review, and The Journal of Early Modern History. He is currently writing a book on the origins of the global drug trade and is on Twitter.

Tiny Books About Cats

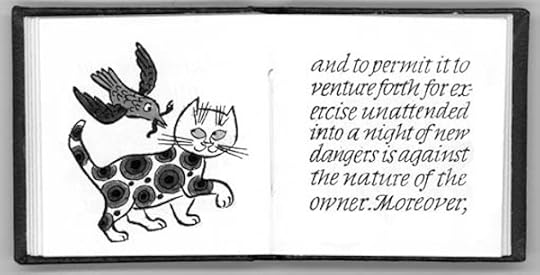

From Adlai Stevenson’s Veto 1949, illustrated by Alice Garman.

Given the passionate nature of bibliophiles, the fanatical devotion of cat fanciers, and the obsessive tendencies of miniaturists, it only stands to reason that when the three join forces, it is to form the most powerful coalition in the world. (Or the least powerful, I suppose, depending on how one quantifies these things.) In any event, what you end up with are miniature cat-themed books, a prominent subgenre.

I fell down this particular rabbit hole when I ran across the miniature bookstore on Berlin’s Torellstraße. It’s affiliated with Freundeskreis Miniaturbuch Berlin, one of many associations of miniature-book collectors; there are miniature-book societies around the world. (The best museum for miniature books is said to be in Baku.)

As Louis Wolfgang Bondy, an enthusiast, wrote in his 1988 book Miniaturbücher von den Anfängen bis Heute (Miniature Books from the Beginnings Until Today),

In this small world, books occupy a place of honor. They join to the great skill lavished on their creation the crowning glory of man’s spirit enshrined in their text. Small wonder then that the ranks of collectors who specialize in them and who cherish, nay adore, them is forever growing … An increasing number of people are convinced of the dictum that small is beautiful.

The workmanship displayed on these tiny objects is indeed remarkable. And there’s still a cottage industries of publishers putting out small runs of limited-edition miniature books. Historically, the genre has involved lots of religious tracts, some erotica, and various improving volumes. But cat literature forms a not-inconsiderable part of the canon. Oftentimes, out of respect for the volumes’ scale, the works printed are excerpts or essays rather than full-length books. The Bromer Booksellers site lists Mark Twain’s Jim Wolf and the Cats, a verse called “Old Pussy, Grave Pussy,” and an illustrated edition of a 1949 Adlai Stevenson veto of a bill by the Illinois State Legislature

that would have required cats to be leashed. “I cannot agree that it should be the declared public policy of Illinois that a cat visiting a neighbor’s yard … is a public nuisance,” Stevenson observes. “It is in the nature of cats to do a certain amount of unescorted roaming.”

Perhaps most intriguing of all is a tract called The Cat as a Musical Instrument, or, The Propagation of the Musical Art Assisted & Advanced by the Feline World, penned by a wag styling himself “Hugh Morist.” The catalog describes this as “an amusing defense of the back-fence serenade. Elegantly printed and fine in blue boards with printed label.”

Needless to say, the body of dog literature is considerably smaller—no pun intended.

Tonight: Prurience!

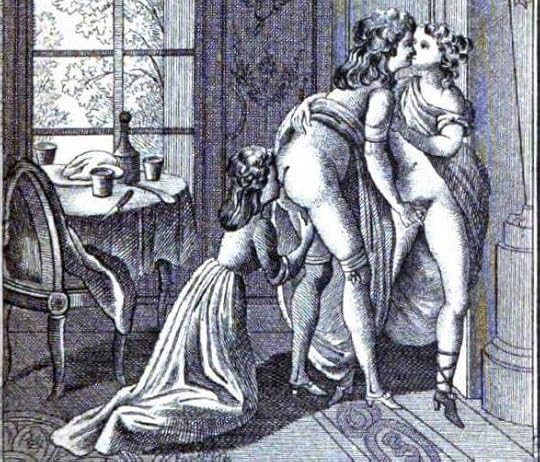

An engraving from the Marquis de Sade’s Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue, 1796.

Tonight at the French Institute Alliance Française, our very own Sadie Stein moderates a discussion called “Obsession & Fantasies: From the Marquis de Sade to Fifty Shades of Grey,” part of the FIAF’s ongoing series on “The Art of Sex & Seduction.”

At what point does a taste for the erotic go from acceptable to perverse? Learn about the impact of the notorious Marquis de Sade on contemporary culture and literature, as well as the current fascination with erotica and kinky sex.

The panelists include Toni Bentley, the author of The Surrender: An Erotic Memoir; Daniel Bergner, the author of What Do Women Want?; and Caroline Weber, a writer and professor at Barnard College. As moderator, Sadie will permit, indulge, censure, steer, and otherwise adjudicate this delicate conversation as she sees fit. Will there be titillating digressions? Psychosexual revelations? Exactly how many of the 120 Days of Sodom will be discussed? Will anyone bring a cat-o’-nine-tails, and if so, will he or she use it? There’s only one way to find out.

The discussion begins at seven. Tickets are available here.

Still Flying High, and Other News

Detail from the cover of the first issue of High Times, 1974.

Ben Bradlee has died at ninety-three: “In his personal vernacular—a vivid, blasphemous argot that combined the swear words he mastered in the Navy during World War II with the impeccable enunciation of a blue-blooded Bostonian—a great story was ‘a real tube-ripper.’ This meant a story was so hot that [Washington] Post readers would rip the paper out of the tubes into which the paperboy delivered it.”

High Times turns forty: “It’s easy to forget how radical an outrider of the counterculture this magazine was. Its editors were (and are) brave, subversive and funny. They’ve tended to take nothing seriously except for one crucial thing: the way so many lives have been destroyed by an inept and misguided war on drugs.”

A well intentioned, poorly executed update to the Scrabble dictionary has turned into “a clusterfuck,” reliable sources indicate. “There are typos, valid words which have been excluded, and invalid words which have been included … The biggest issue among competitive players is the lack of a publicly available electronic version of the new list … Because of Hasbro’s copyright, and the absence of a public electronic list, errors have been tedious to identify.”

Tolstoy’s 1889 novella The Kreutzer Sonata was a famously caustic attack on his wife, Sofiya. She struck back with “Whose Fault?”, a rebuttal in the form of a short story: “Like Tolstoy, Sofiya criticizes the sexual double standard, but she’s far more sympathetic to women, who are kept in ignorance until marriage, then expected to satisfy their husbands and remain beautiful and docile through a long series of pregnancies and betrayals.”

“There was a long period when an outhouse was a perfect convenience, and a well-built one could be a luxury good. The Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum in Wethersfield, Connecticut, is trying to recapture their golden age with an unusual kind of restoration project: The refurbishment of three high-end outhouses—or privies—from the late eighteenth century.”

October 21, 2014

The Fruit of Another

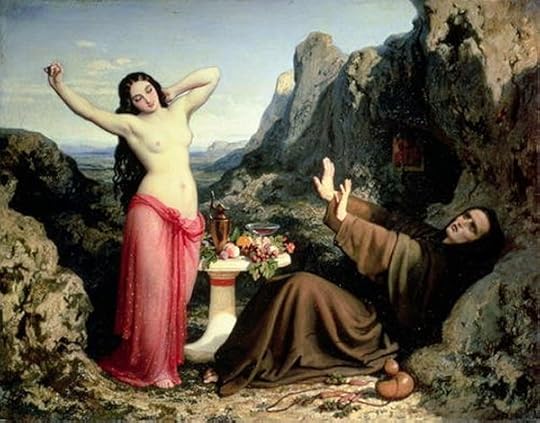

Dominique-Louis-Féréa Papety, The Temptation of Saint Hilarion, 1843–44.

Octave Tassaert, The Temptation of Saint Hilarion, 1857.

Let’s talk about temptation, because it’s Saint Hilarion’s feast day. A fourth-century anchorite who followed the ascetic precedent of Anthony the Great, Hilarion lived for most of his life in a desert in Syria Palaestina, where … not much happened, presumably. He refused to take food before sunset and, perhaps as a result, faced a slew of hallucinations temptations. These he avoided, being saintly. When at last he rejoined civilization after many decades in the wilderness, he didn’t much care for society—so many people!—so he retreated into austerity again, in Dalmatia and then in Cyprus, where he died.

I’m simplifying things a bit.

The man wrought some miracles, for instance, but those are not my concern.

Much of what we know about Hilarion—the name is from the Greek hilaros, meaning cheerful, not super funny, though neither seems to describe the Hilarion in question—comes from a chronicle written by Saint Jerome in 390 A.D., a strange, captivating, and fittingly arid read, particularly in regards to Hilarion’s temptations:

Satan therefore tickled his senses and, as is his wont, lighted in his maturing body the fires of lust … So many were his temptations and so various the snares of demons night and day, that if I wished to relate them, a volume would not suffice. How often when he lay down did naked women appear to him, how often sumptuous feasts when he was hungry! Sometimes as he prayed a howling wolf sprang past or a snarling fox, and when he sang a gladiatorial show was before him, and a man newly slain would seem to fall at his feet and ask him for burial.

And there’s the unnerving specificity with which Jerome describes Hilarion’s diet:

From his twentieth to his twenty-seventh year, for three years his food was half a pint of lentils moistened with cold water, and for the next three dry bread with salt and water. From his twenty-seventh year onward to the thirtieth, he supported himself on wild herbs and the raw roots of certain shrubs. From his thirty-first to his thirty-fifth year, he had for food six ounces of barley bread, and vegetables slightly cooked without oil. But finding his eyes growing dim and his whole body shriveled with a scabby eruption and dry mange, he added oil to his former food.

I love the anticlimax of that remedy: faced with “a scabby eruption,” Hilarion simply lubes up his food. End of subject. From soup to nuts, Jerome’s account is fixated on Hilarion’s nutrition, as if a detailed summary of what he ingested could best convey the tortures of fasting.

Hilarion’s temptations inspired two very striking—and very different—French nineteenth-century paintings, both of which testify to his suffering more acutely than Jerome’s storytelling. The first, by Dominique-Louis-Féréol Papety, sees an almost catatonic Hilarion visited by a topless seductress with an elegant array of fruits, wine, and hors d’oeuvres, a surreal counterpoint to the forbidding landscape. What a brilliant thought on Papety’s part to have Hilarion’s arms outstretched—in protest as much as in longing, it seems—his face sick with fear and confusion.

The second is by Octave Tassaert, and it’s more conventionally harrowing: Hilarion stoops with a jury-rigged cross in his hand, bearing down in determined, moonlit prayer. In the air behind him are dozens of buxom temptresses in various stages of materiality, fumbling over one another to make an erotic impression; one of them offers a truly formidable chalice of red.

Even if you, like me, were raised Catholic and now practice an active disdain for its pageantry, the paintings are chilling metaphors for enticements of all kinds. As another account of Hilarion’s life says, “his mind was haunted and his imagination filled with impure images, or with the vanities of the theatre and circus”—and those are vanities we can all relate to, even those among us who aren’t the circus-going type.

Counterpunch

On a sentence by Robert Walser.

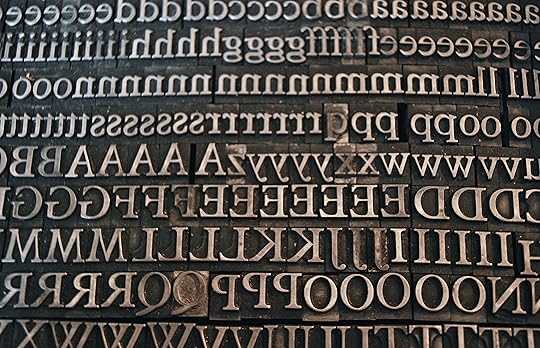

Plantin letterpress type. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

It is worth remembering that there once was a time when every letter, number, and punctuation mark printed on paper started life as a sculpture. Someone had to make the letterforms by hand, in three dimensions; the individual characters could all look alike because they were all molten metal poured into the same mold (hence: font), but someone had to make the molds. The first time this hit home for me was when I thought about changing the type size in letterpress days: rather than pressing CTRL+> or CTRL+

They’re sculptures, not drawings, because the angle and depth of the sides affect the look of the printed letter. These can be adequately controlled along the outline of a letter, but for the inner lines and negative spaces—the triangle in an A, the near-rectangles in a serifed E—it’s hard to gouge out the cavities precisely enough. So a D, for instance, would start out as a rod of steel whose tip is carved into a semicircle: a counterpunch, tempered to be harder than the steel of the punch. Pounding this into the flat end of another rod makes a semicircle-shaped hole. Carving around the hole makes a raised D, or rather a raised ᗡ. Slamming that rod into another block of metal (softer than the steel, usually copper) makes a ᗡ-shaped hole, the matrix. Pouring molten metal into that and letting it cool produces the piece of type. Then the letters are set into a stick, in reverse order; clamped together; and ink is rolled onto the surface before it is flipped again onto a sheet of paper, leaving a D-shaped black mark.

By my count, that’s five turnarounds: counterpunch, punch, matrix, piece of type, printed character. There’s a strange reversal in time, too, since every other kind of counterpunch (in boxing, in debate) reacts to the punch, while here it pre-exists the punch. I’ve never gotten tired of replaying the transformations in my mind—positive, negative, positive, negative, mirrored, counting and recounting them, following the fate of a raised waning half-moon to the empty space in a printed D. The dreamy dizziness felt like what art is.

I’ve since found the same effect in a sentence I’ve translated by the Swiss writer Robert Walser:

Der weite See glich einem Kinde, das völlig still ist, weil es schläft und träumt.

The large lake resembled a child who is completely silent because asleep and dreaming.

How can a large lake be like a child—isn’t smallness what defines a child? It turns out they are alike in their silence, even though neither form of life is generally known for being completely silent. The child is silent because asleep, which explains it. But the child is dreaming … and with that a universe opens up within the child, who is large after all, containing worlds wider than even the largest lake. The animate child, stilled, is brought back to life, an inaccessible inner life. I am happy for this child; I love this child, as much as Walser loves and makes me love his lake.

The sentence comes in the middle of a series of such reversals, all helping to set us afloat in Walser’s dreamworld:

The high mountain, drawn down by gentle forces, sank mildly with a wonderful gesture into the depths, where the smooth surface of the water gracefully reflected it. The large lake resembled a child who is completely silent because asleep and dreaming. The calm reigning everywhere all around was made yet stronger, and bigger, by the delicate rush of the rain; the silence, rustling noiselessly back and forth like an evening bird, experienced no lessening from the timorous light wind shyly wafting from the west.

Sinking and rising, back and forth, big strong calmness, rustling silence. It may not matter what the opposites are—the pattern itself is enough, a flipping of the counterpunch. Art has to open something up inside us, an inner sky as Rilke calls it. It sets up two opposing poles, pulls them as far apart as possible, and maintains the tension or communication between them—in the back and forth, the space between is where the feeling lives.

Walser’s German sentence has a harmonious balance and rhythm, with the three comma-separated parts separated, too, by pauses between unstressed syllables, until the strong finish. An optional, slightly archaic word form—Kinde instead of Kind—makes the pattern perfect. Here’s how the syllables scan:

∪ / ∪ / ∪ / ∪ / ∪

Der weite See glich einem Kinde,

∪ / ∪ / ∪

das völlig still ist,

∪ ∪ / ∪ /

weil es schläft und träumt.

I don’t scan every sentence I translate; I’d never scanned this one until the translation was done and I realized how much the sentence moved me. If I had done it beforehand, I could have matched the syllables in English—“The spacious lake was like a child who is wholly silent while he sleeps and dreams”—but that wouldn’t have been a better sentence in this case, especially since it forces a gender onto our sleeping mystery. My intuitive translation matched Walser’s 4-2-2 stresses and had a rhythm of its own, with exactly matching patterns in the second half of rushed rise and quick falling off.

∪ / /

The large lake

∪ / ∪ ∪ /

resembled a child

∪ ∪ ∪ / ∪ / ∪

who is completely silent

∪ ∪ ∪ / ∪ / ∪

because asleep and dreaming.

If we had a grammar of prose rhythm, we would know more about the difference between Walser’s dreams in German and in English, or maybe children’s dreams in German and in English. The German is stately and regular, a march with a pause for each change in direction; the English starts stronger and fades gently and evenly away, like the splash and ripples of a stone tossed into a large lake. In either language, the words are asleep until we dream them.

Damion Searls, the Daily’s language columnist, is a translator from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch.

Trick Lighting

Photo: Walt Stoneburner

I ran into the guy while I was taking a walk through what is now called the Columbia Waterfront District—but then, this was nearly ten years ago.

“Excuse me, do you live around here?” he said. I thought he wanted directions, but it turned out he was a location scout for a small indie film. Did I have a railroad apartment, he wondered, in an older building? I did. And would I be willing to let them shoot there for a few hours?

They came to check it out a few days later. For some reason, their approval seemed important; I scoured the place and had fresh coffee brewing (realtor-style) when they came in. This time it was a director—a middle-aged man—and a few assistants. They conferred a great deal about angles and light and what they’d have to do to make the place work before giving their qualified approval. A shooting time was set.

I had grown to hate that apartment. It had looked nice when we moved in a year before, and had felt like a fresh start. But then had come the months of unpacked boxes and unhung pictures and the day I had a burst of enthusiasm and tried to arrange everything myself. And then the anger at my slapdash methods and the walls of crooked frames, my tears. My boyfriend hated his job and, I think, me. I would walk through the door and find him sitting in the dark. We almost never had people over. And the row of small, windowless rooms, which had initially felt cozy, now looked dark and dreary. Our landlady, who it seemed was in violation of about every housing code, had long since fled the state, so any maintenance—of peeling paint or faulty wiring—was out of the question. I was glad to be forced to clean, to open ourselves up to scrutiny.

On the day of the shoot, the crew arrived early. I had again made coffee, and augmented it with doughnuts. My boyfriend answered questions about outlets and wall supports and the group of five or so began experimenting with lighting effects, suspending cords and hanging sheets and rearranging furniture. They were all very officious and official and it was thrilling. “I love this apartment,” said one of the crew—handsome, French, about our age. He indicated the rows of paintings—the work of my boyfriend’s grandfather—the thrift-store furniture, the stacks of books. “This is what I want,” he said.

Later, the cast, wardrobe, and makeup showed up. There were three actors: a pretty young woman with a theatrical mien; an older, intense man with silver hair; and a rather sullen young guy. Makeup, hair, and wardrobe would take place in our small bedroom. My boyfriend and I went to a movie to get out from underfoot. I remember laughing as we went.

When we got back, they had started shooting. We were allowed in, and sat quietly on our bed with the crew, looking at a copy of the script. I noticed that the hair and wardrobe women were both wearing pairs of my shoes. I was absurdly flattered, although I knew even then that in the retelling I’d pretend to have been quizzical and irritated.

The movie was about a brother and sister—the two young people—bonding on a road trip to go see their drunk father. Our apartment belonged to the gray-haired guy, the sister’s older boyfriend. He was apparently supposed to be a professor. First they ate some Chinese food in silence at our dining-room table (to show they were estranged), and then sat in the living room and had a conversation meant to convey pain, distance, and disconnection.

“Haven’t you had enough?” the girl would say coldly as he opened a beer.

“Since when are you a teetotaler?” he’d sneer.

They did this scene over and over.

Between takes, the cast interacted; the older guy was talking rather grandly about some other film he was working on and asking the young costar about her training. My boyfriend and I tried not to meet each other’s eyes or snicker. After all, we had volunteered for this—or I had. We were forced to suspend judgment; I found it was relaxing.

It had gotten very late. Someone knocked on the door—a furious downstairs neighbor who couldn’t sleep. I apologized; there was nothing we could do. “This is completely unacceptable,” she said.

They had to shoot one final scene. This time, the brother character slept on the couch, exhausted, while his sister stroked his hair. I wasn’t sure whether there was supposed to be an incestuous subtext or whether it was just clear that the two actors were sleeping together.

The movie was appallingly bad, almost unbelievably bad. There was no chance anything would ever come of it; nothing has, although I see it appeared at a tiny film festival, and there is a trailer online, even worse than I remembered. But everyone approached the enterprise with the seriousness of a real project. And in the false, soft glow of their carefully arranged lights, the apartment looked beautiful. Many years after we’d broken up and moved out, I found a still shot in our apartment, and sent it to my old boyfriend. “Haven’t you had enough?” I captioned it.

It took over an hour for them to strike the set, not least because most of the crew left. The French guy and one other stayed behind to wind the lights and rearrange the furniture. We helped; it was nearly three A.M. “Don’t worry about moving it back,” urged my boyfriend.

“Beautiful place,” said the French guy, looking around one last time. “Perfect.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers