The Paris Review's Blog, page 655

October 10, 2014

Staff Picks: Kids Tossing Guns, Phenomenal Hard-ons

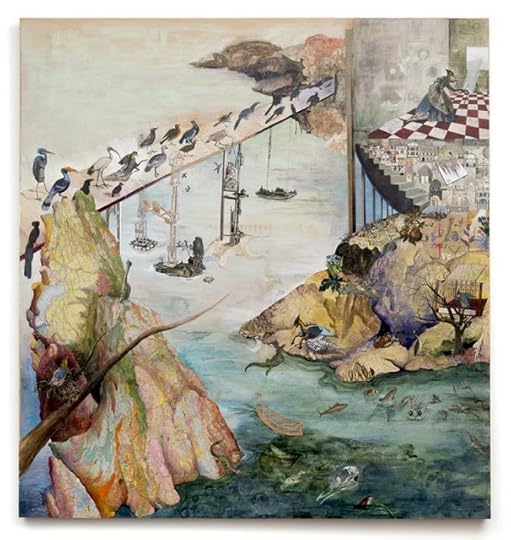

Josh Dorman, A Life Led, 2014, ink, acrylic and antique paper on panel, 60" x 56."

Despite the fact that the workmen next door have been playing the catchiest pop songs from the past thirty years for a few days now, I managed to tune them out long enough to read Jon McNaught’s Dockwood, a book that, though spare in dialogue, is oddly focused on sound, or, more accurately, on a symphony of silence. The book comprises two comics stories set in the titular British town, a leafy, suburban sort of place that is settling into the early days of autumn and into what seems like a permanent state of dreamy twilight. The first story follows a man named Mark through his day as a kitchen porter at a nursing home. The opening pages of the book are soundless, save the munch of a mouse eating a chip and tink of colliding hanging straps on a bus. But the quiet of early morning is surprisingly vivid. It creates a rhythm of reading—the pages are divided into tiny panels mixed in with larger ones—and plunges you instantly into the narrative. The second story, about a boy delivering newspapers, works according to the same principles. It’s a stunning effect. And McNaught, who is also a printmaker, makes each panel contemplate the smallest of life’s details. —Nicole Rudick

This Saturday is your last chance to see “Whorled,” Josh Dorman’s vast and imaginative solo show at Ryan Lee Gallery. Dorman paints vibrant, dreamlike landscapes and festoons them with found images: illustrations, fragments, and diagrams from old textbooks and catalogs, all of them from the seemingly prelapsarian period before photography, and all carefully (though still jarringly) collaged into the paintings. Parades of flora and fauna coexist with kids tossing guns; lakes are made of hammers, mountains grow from maps. You’d expect all this to devolve into chaos, a kind of jackdaw’s nest, but Dorman’s compositions are precise, even orderly, which makes them all the more uncanny—as beautiful as they are, the paintings evoke a state of basic contradiction that has a way of getting under your skin. —Dan Piepenbring

Even if it’s only an hour and forty minutes, Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja was one of the most difficult films I’ve sat through, and I’ve survived everything from Sátántangó to Snakes on a Plane. Moving at a glacial pace, with a plot as complicated as Waiting for Godot’s, the film follows the Danish surveyor Dinesen in nineteenth-century Patagonia as he tries to find his missing daughter in the otherworldly landscape. In long, carefully composed takes, Alonso declares his commitment to a minimalist cinema, one that blends narrative with documentary; the film is more about Dinesen’s relationship with the landscape itself than any miraculous reunion with his daughter. I walked out of the screening completely perplexed by the experience, but since then I haven’t been able to shake the film. It’s like a dream you hope to revisit until some sort of answer reveals itself. —Justin Alvarez

This week’s New Yorker includes “Scheherazade,” a gorgeous new story by Haruki Murakami with quiet undercurrents of the fantastic. Murakami writes of the intimacy between a housebound man, Nobutaka Habara, and his caregiver. Though Habara doesn’t seem to suffer from any ailment in particular, he’s always receiving the ministrations of Scheherazade, a woman he names after the queen in One Thousand and One Nights. She brings him provisions and takes him to bed, and then becomes a raconteur, telling him stories of lamprey eels or her preternatural youth, leaving Habara invested in her company but hyperaware of its mutability. Their relationship is resigned, mercurial, and that dynamic interests Murakami: “I occasionally think that, in our heart of hearts, we all may be seeking situations like this one—where our free will doesn’t apply and (almost) everything is determined by someone else, where each day must be lived according to the conditions that someone else has laid down … What interests me is trying to ferret out the identity that is so deftly concealed within the accumulation of such passive operations.” —Caitlin Youngquist

If you happen to be looking for a short-story collection that features talking fish, immortal dogs, and girlfriends that turn into fat, hairy men at night, Etgar Keret’s The Nimrod Flipout is your best bet, maybe your only bet. The Israeli author’s particular brand of magic realism comprises equal parts normalcy and sleeping pill–induced dream puddle. But underneath the phantasmagoria of these stories and their unusual titles (one story is called “Actually, I’ve Had Some Phenomenal Hard-ons Lately”) lies an entirely serious commentary that grapples with issues of emotional expression and individuality. The collection’s deeper implications are charmingly concealed but are definitely present—just ask the fish. —Alex Celia

Profanity-Laced Tirade

No cussing! A postcard ca. 1909.

The following human-interest story ran recently on Metro UK:

A grandmother who once hated the idea of swearing now turns the air blue after a stroke left her unable to control her potty mouth ...

‘Before I had a stroke I would still get annoyed at things but I could control my upset, however now I just can’t help it,’ she said.

The retired bank worker says her swearing particularly irks her husband, as he used to be a head teacher and therefore has an obvious aversion to swearing.

She has introduced a swear box since her stroke last January in an attempt to train her brain, and is also receiving help from psychologists.

Of course, nowadays, not cursing is more noteworthy than swearing like a sailor. I’ve never been very good at cursing, personally. There was a very brief vogue in my middle-school homeroom for trying to get me to curse; it corresponded with general mockery of my uptightness. But I stand by that; I think I understood that however ludicrous a tiny, flannel-clad nerd trying to be dignified might have been, the same tiny, flannel-clad nerd peppering her speech with profanity would have been more ludicrous still. The problem is that I never learned to do it, and to this day in moments of extremis will give voice to ejaculations like, Oh, gosh! Gee whiz! Drat! And, when things get really bad, Darn it!

But then, I don’t come from much of a swearing family. Even the grown-ups didn’t go in for what my mother calls “coarse language,” and we kids wouldn’t have dared. (As with many normal things, however, my brother seems to have taken to it much more easily than I.) With the exception of the famous occasion on which she listed cunt on her Boggle scorecard—“isn’t this a word?”—my grandmother never used words stronger than fouled up. As for my grandfather, he managed to invest his gin-playing epithets—“DAMMIT!” “I’LL BE DIPPED!”—with such rage and menace that the words themselves were almost immaterial.

Cursing may coarsen the culture and display a lack of verbal imagination, but it is a useful skill to have. Back when those kids used to tease me, I remember replying with dignity that I like to be able to use the same language with my grandmother that I do the rest of the time, and thinking that this was a really good answer. But then, there are grandmothers and grandmothers. As the article tells us, Preston “has even called her grandchildren ‘little b******s’ when they were playing up.”

Fifty Shrinks

Sebastian Zimmermann, Jamieson Webster, PhD.

It’s an experiment in what your life might be like if you speak freely to another person—speak and allow that person to show you the ways in which you stop yourself thinking and speaking freely. I don’t mean by that that it doesn’t change symptoms. I know by my own experience that it does. But I think the most interesting thing about it is its unpredictability. If you buy a fridge, there are certain things you will be guaranteed. If you buy a psychoanalysis, you won’t be. It’s a real risk, and that also is the point of it. Patients come because they are suffering from something. They want that suffering to be alleviated. Ideally, in the process of doing the analysis, they might find their suffering is alleviated or modified, but also they might discover there are more important things than to alleviate one’s suffering.

—Adam Phillips, The Art of Nonfiction No. 7

Sebastian Zimmermann’s new monograph, Fifty Shrinks, does exactly what it says on the tin: it features photographs of fifty therapists and analysts in their offices, which are, according to an essay in the book by the architect Elizabeth Danze, “floating vessels, places of sanctuary … [when] a patient reflects on the trajectory of his or her therapy, an indelible part of that recollection involves the space in which it took place.”

The concept should be twee or ponderous, and at its most obvious it can be—the tropes of analysis are all here, the long couches, solemn shelves of leatherbound books, thick curtains and dark woodgrain, prominently hung diplomas, all the shorthand for erudition—but most of Zimmermann’s portraits are surprisingly lively. The offices (and the people in them) are far from clinical. In fact, Fifty Shrinks is more or less an object lesson in eccentricity: there are offices furnished only with folding chairs or decorated with terrifyingly vibrant floral wallpaper, a therapist whose desk is consumed by Rolodexes, and a therapist holding ominous court at his chess set.

You can see more of the photographs here.

Sebastian Zimmermann, Albert Ellis, PhD.

Bovary at Market, and Other News

From an 1897 illustrated edition of Madame Bovary.

“If there is a politics of the white-collar novel in the United States, it is this: office fiction is deliberately and narrowly construed as being about manners, sociability, gossip, the micro-struggles for rank and status—in other words, ‘office politics’—rather than about the work that is done in offices.”

Jane Smiley on her absent father and her upbringing: “A girl who is overlooked has a good chance of not learning what it is she is supposed to do. A girl who is free can grow up free of preconceptions. Sometimes, from the outside, my work and my life look daring, but I am not a daring person. I am just a person who was never taught what not to try.”

The farmers-market scene in Madame Bovary reminds of how the social function of such markets has evolved: “If Emma Bovary were alive today in the small town where I used to make my home, she might be scanning the crowd on market day, but she wouldn’t be thinking ‘yokels.’ She might have a thing for the guy who sells microgreens, the one with the gray ponytail and the lingering smile who used to do something in tech.”

Shirley Temple as a troubling icon of the Depression: in the thirties, “the child became both commodity and consumer. And Shirley was the ultimate product, her managers capitalizing on the mania for cuteness … Children wanted both to have and to be Shirley. In addition to coveting the dolls and dresses, girls from Iowa to Bombay entered look-alike contests. But just what possessive desire did Shirley arouse in adults? The objects of her attention were almost invariably adult men. There was … scarcely a male lap she did not climb into on or offscreen, and there was an extravagant amount of manhandling in the films.”

Bemoaning the increasing role of the dystopian in science fiction, Neal Stephenson has started Project Hieroglyph: “The concept at the core of Project Hieroglyph is that science fiction creates potent images of scientific progress, images that Neal Stephenson dubs hieroglyphs, and that by making more positive and optimistic hieroglyphs, [sci-fi] can help make a better world.”

October 9, 2014

How to Win the Nobel Prize

A close reading of the Swedish Academy’s citations.

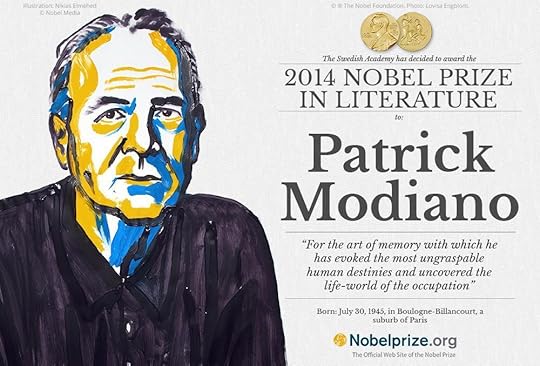

Reading the news about Patrick Modiano today, I was struck by the insipidness of the Nobel Foundation’s citation: “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation.” It bears all the hallmarks of an overblown blurb, one of those in which a bold, gimlet-eyed novelist is elucidating the now, or a limpid, singular poet is saying the unsayable. (Very few poets are saying the sayable these days, if our blurbs are to be believed.)

Let’s unpack this citation, beginning with this business about “the art of memory,” which doesn’t seem like much of an art to me. (To conceive of it as such invites a corny geriatric punch line: “Just wait till you start forgetting so much!”) Granting that it is art, is it really the art through which Modiano “evokes”? That would have to be his writing. If he’d simply sat at his desk lost in memories, he wouldn’t evoke much more than sighs. For that matter—can one really “evoke” a destiny, and, having been evoked, is that destiny still “ungraspable,” let alone the most ungraspable? Who’s to say that one destiny can be grasped more easily than another? (“He was destined to be a pediatric podiatrist—he saw it plain as day.”) Then there’s this murky concept of the “life-world,” which sounds like something out of Heidegger—wouldn’t one word or the other have sufficed? To speak of a life-world implies its negative, the death-world, which, despite our best efforts, has never been uncovered.

Drafting these citations must be painstaking, fairly joyless work. This one, at least, reads like an act of circumlocution by committee; the choice to append “the most” to “ungraspable” may have occasioned hours of debate. And for what? The final result could apply to anyone; in the broadest terms, not just every writer but every person in history has practiced the art of memory, evoking destinies and uncovering life-worlds.

The Swedish Academy has more than a century of history to contend with, too—their citations are all on record, and perhaps they’re wary of leaning too much on expectable, well-worn adjectives. Certainly they have reason to worry: if you read through all the citations, you’ll start to detect certain patterns. Any aspirant Nobel Prize–winner should take note—these may hold the key to victory.

For starters, there’s idealism: it’s everywhere. When Alfred Nobel established the prize in 1895, his will stipulated that the judges should choose a writer who has produced “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”—a vague proviso, and one from which the Academy has since drifted somewhat. In the beginning, though, idealism was the order of the day, which made for some repetitive citations. In 1901 they cited Sully Prudhomme, the first-ever laureate, “in special recognition of his poetic composition, which gives evidence of lofty idealism, artistic perfection and a rare combination of the qualities of both heart and intellect.” Only eight years later, in 1909, Selma Lagerlöf earned the prize “in appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception that characterize her writings.” In 1915 Romain Rolland won it “as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production.” Two years after that, the Academy at last dared to switch things up a bit, commending Karl Adolph Gjellerup “for his varied and rich poetry, which is inspired by lofty ideals.” They could scarcely find it in themselves to commend ideals that weren’t lofty—though I struggle to name a single ideal that isn’t.

The Academy also goes in for traditions a lot—especially, for whatever reason, Spanish and Russian traditions. They’ve issued citations saluting “the great traditions of the Spanish drama,” “the illustrious traditions of the Spanish drama,” “the classical Russian traditions,” “the great Russian epic tradition,” “the indispensible traditions of Russian literature” and “the tradition of Spanish poetry,” with a few other traditions thrown in for good measure. Easy enough, you might think—I’ll just stick to tradition and have this thing locked up in no time. Not so fast: contemporary appears seven times over the years.

It goes without saying that you should be great—that word pops up in eleven citations—but it also helps if you’re epic (also eleven). Oh, and fresh! Always keep it fresh. Your inspiration has to be fresh, you must exude “fresh originality”—no stale originality, please!—a “freshly creative style,” “fresh and beautiful verse” that “gives us fresh access to reality,” “endowed with freshness.” If you can’t muster that kind of thing, try instead to be lyrical (seven) or to master the mastery of masterpieces (seven again). And if you’re questing or searching for anything, best to make it truth (five). Last, keep it real: reality, realism, and realistic appear nine times.

By my lights, the freshest, realest, most masterly citation is probably the one for Harry Martinson, from 1974: “for writings that catch the dewdrop and reflect the cosmos.” It’s just as nonsensical as Modiano’s, but with much finer prosody. Cosmos appears in two citations, actually, meaning it’s of greater concern to the Academy than curiosity or vitality—those only receive one mention apiece. And so goes my advice to young writers: don’t be curious. Be cosmic.

Psychodrama

Andrew Stevovich, Popcorn, 2008.

To those of us who enjoy seeing movies alone, the practice does not require any defense; it’s one of life’s greatest pleasures. While—obviously—everyone likes seeing a film with a like-minded friend, and while some (The Room springs to mind) derive half their pleasure from the shared experience, there’s a lot to be said for the total lack of self-consciousness inspired by a solo venture. The practical benefits are self-evident—seeing what you prefer, sitting where you like, leaving if you want—but those of reacting in a vacuum are even greater. However independent-minded you might be, it is hard not to be aware of your companion’s amusement, or disdain, or (in the case of my dad) checking of his watch whenever he gets bored. How much more relaxing to sit alone and let your impressions form, and then digest and recollect in tranquility.

Last night, I went to see Gone Girl. It struck me as a perfect movie to see alone; unlike much of the English-speaking world, I didn’t know the plot, and looked forward to thoroughly losing myself in an absorbing story. With this in mind, I purchased a ticket for one of the stand-alone seats at the back of the theater; this multiplex has assigned seating. I figured the privacy—the space to react—mitigated the distance.

But when I arrived for my showing, it was to find that, in fact, these seats were not stand-alone; while my seat was indeed isolated from the general aisle, it was one of a pair. And there was an older man already occupying the other half of what, basically, amounted to a love seat. I should perhaps add here that this theater is famously romantic; since its 2013 remodel, its fully reclining, softly padded seats, with their removable armrests, have been a destination spot for teens on the make. Not only would I not have privacy; I would be relegated in bizarre intimacy with this stranger. I had a horrible flashback to the time in seventh grade when I was invited to a bar mitzvah where I didn’t know anyone and we were seated in the order in which we filed in and I ended up sitting next to three random boys for the duration of a joust at Medieval Times.

Appalled, I scampered away without my seatmate seeing me and sat down in another, empty, pair, only to be routed five minutes later by the seats’ rightful occupants—a couple. This happened twice. It was clear that the show was sold out, and that I’d have to take my assigned place. I slipped into my seat sullenly, didn’t make eye contact (so as to better preserve the illusion of privacy) and slid as far as I could to the right. My neighbor lowered the armrest.

Chill out, you neurotic fool, I told myself, Once the film starts, you won’t even know he’s there. Then, of course, came the opening strains of that slow reboot of “Crazy in Love” that indicates the Fifty Shades of Grey preview, and everything was unspeakably awkward.

I wish I could say matters improved during the film, but the truth is that, every time I forgot myself enough to react at all—to laugh or gasp—my neighbor would echo me. I’d chuckle and then he would—and only then! Did he want my approval? Was he so unsure of his own responses as to need the validation of a stranger’s? Plus, it made me uncomfortably aware of my own actions. Why had I laughed at that not-funny line? And if I laughed now—experimentally—would he follow suit? The answer was yes. It was like the worst date in history.

I planned to run. I wanted to save us both the awkwardness of acknowledgment. And I was the first one out of the theater. But as I stood up to go, I gave into a sudden impulse, grabbed my half-eaten box of Junior Mints, and thrust it awkwardly into his hand. Then I bolted.

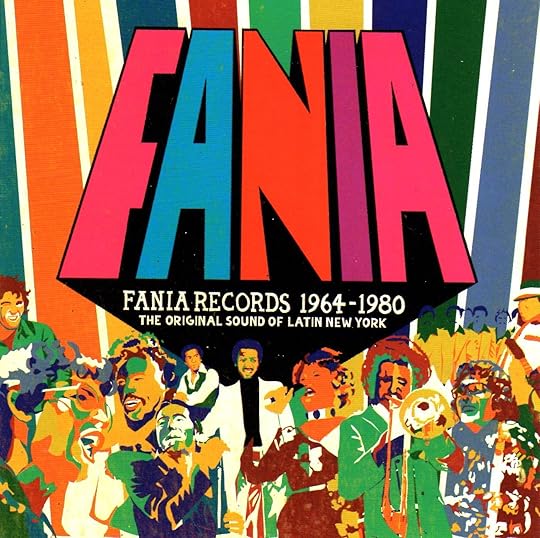

Fania at Fifty

The rise of a salsa empire and the decline of boogaloo.

Photo: Courtesy of Codigo Group

Fania Records, the legendary Latin music label, has been celebrating its fiftieth anniversary with a series of events in New York and Los Angeles, its opening salvo a Central Park show last June spotlighting salsero Roberto Roena. It felt, indeed, like a party. Hundreds of dancers flooded the area in front of the stage. Those present merely to spectate were forced backward. Scattered around the perimeter were those less enthused: numerous youths lolled against concession tents and information booths, occupied with handheld devices, presumably corralled into coming by parents either filled with missionary zeal or simply unable to get a babysitter. The sharp contours of the audience underscored the relationship between the label’s haloed status and the historical circumstances that enabled its ascent.

In its sixties and seventies heyday, Fania was the most powerful force in the Latin music industry, and salsa was the most powerful force in Latin music. The depth of the connection between label and genre is pronounced. Ask die-hard fans to list their favorite figures from salsa’s golden age, and nine out of ten answers will be artists whose résumés include Fania for at least a record or two (Eddie Palmieri, Tito Puente), if not for significant stretches of their careers (Celia Cruz, Willie Colón). It is commonplace to liken Fania to Motown. The parallel fits, almost. Imagine if Motown, after a few years of competing with Atlantic and Stax/Volt, had decided to buy them out. That’s what Fania did, more or less, when it acquired its main rivals, Alegre and Tico.

Fania was an unprecedented financial engine, exporting Boricua and Nuyorican culture all over the world. The label held what musician and ethnomusicographer Christopher Washburne calls a “monopoly on all aspects of the salsa industry,” controlling “recording contracts, concert promotion, and radio airplay.” Labelmates from different bands performed and recorded as the Fania All-Stars. This was synergy before synergy, when it was still called monopoly, and it created salsa audiences in Colombia, Nigeria, Russia, Japan, et cetera.

But the familiar narrative of Fania as salsa, salsa as Fania—the narrative on display this June—is only half complete, eliding as it does another genre, the buried foundation on which Fania was built: Latin boogaloo.

* * *

“Latin music” as a category is a cheat. We use the term to refer to a wide and overlapping set of traditions, from the son jarocho folk songs of Mexico’s Caribbean coast to the electro-cumbia hip in Buenos Aires today. Grouping this music together reveals how stylistically broad Latin music really is. The traditions share, for example, musical elements catalyzed in the Caribbean along the slave routes, where African influence mingled with music indigenous to the islands and coasts and traces of European styles. But this intersection propels genres as apparently varied as reggae, New Orleans brass, and son cubano. In truth, practically all popular forms of popular music over the last century exhibit Caribbean influence: Jelly Roll Morton was talking about the “Spanish tinge” nearly a century ago.

“Latin music” as a category is a cheat. We use the term to refer to a wide and overlapping set of traditions, from the son jarocho folk songs of Mexico’s Caribbean coast to the electro-cumbia hip in Buenos Aires today. Grouping this music together reveals how stylistically broad Latin music really is. The traditions share, for example, musical elements catalyzed in the Caribbean along the slave routes, where African influence mingled with music indigenous to the islands and coasts and traces of European styles. But this intersection propels genres as apparently varied as reggae, New Orleans brass, and son cubano. In truth, practically all popular forms of popular music over the last century exhibit Caribbean influence: Jelly Roll Morton was talking about the “Spanish tinge” nearly a century ago.

Latin music, then, is better understood chronologically. In the forties and fifties, mambo and Latin big-band jazz became the first commercially viable Latin styles in the United States. At their peak, these genres were dominated by Cuba—bandleaders such as Pérez Prado and Machito were at the forefront of the fad, and U.S. musicians looked to Cuba for trends and innovations. America saw a steady influx of Cuban musicians to fill band ranks.

Relations cooled after Cuba’s 1959 revolution and the U.S. trade embargo. At the same time, Puerto Rican immigration to the U.S. was exploding. Between 1940 and 1960, the Puerto Rican population in New York increased, without exaggeration, one-thousand percent. Puerto Ricans became the most visible Latino community in America. The year 1961 saw the releases of Jesús Colón’s A Puerto Rican in New York; in the dance halls, bandleaders of Puerto Rican descent—such as Puente, Joe Cuba, and Ray Barretto—began their rise.

This was the scene into which lawyer and ex-cop Jerry Masucci and the multi-instrumentalist Johnny Pacheco launched Fania in 1964. The musical styles driving early Fania records were the Cuban-derived charanga and Pacheco’s twist on it, pachanga. Soon, Fania found its first signature sound: Latin boogaloo–sometimes called shing-a-ling, sometimes Latin Soul, sometimes written bugalú. The term boogaloo itself either connotes dance-oriented, blues-derived music—roughly equivalent to boogie—or an African American dance popular in the sixties: that dance probably gives Latin boogaloo its name.

Genres are slippery. The best-known definition of Latin boogaloo was coined by the bandleader Pucho Brown: “cha-cha with a backbeat.” (Cha-chas are set in traditional Afro-Cuban two-three clave, and a backbeat borrowed from rock and roll or soul would emphasize the second and fourth beat of the measures.) But this definition could fit many forms of popular music. I’d venture to say a boogaloo recording usually has some combination of the following: Latin percussion playing Afro-Caribbean rhythms; chords and song structures borrowed from soul/R & B/doo-wop (themselves derived from gospel and blues); English lyrics, often a bit goofy; and a party atmosphere created by the shouts of the band or an in-studio audience. Much of boogaloo has an air of amateurism to it, a bubblegum simplicity that encourages even neophytes to hit the dance floor.

To Izzy Sanabria, an early Fania collaborator, boogaloo encapsulates what made the label innovative: it targeted a new generation of record buyers, “Puerto Rican baby boomers, the sons and daughters of the huge Puerto Rican migration.” Sanabria, sometimes called “Mr. Salsa,” was a triple threat: an accomplished visual artist, stage presence, and writer. He designed many of Fania’s iconic album covers, he emceed Fania’s showcase events, and he published Latin NY Magazine in the seventies.

Speaking to me by phone, Sanabria pointed out that his peers’ parents migrated to the U.S. as laborers, with very little education, and that the young Puerto Ricans of the sixties showed only a tepid interest in the previous generation’s music. Instead, they identified with the African American music that was at the forefront of U.S. consciousness, and often the top of the charts. Thus, Latin boogaloo, musically and culturally hybrid, became “the biggest thing in New York.”

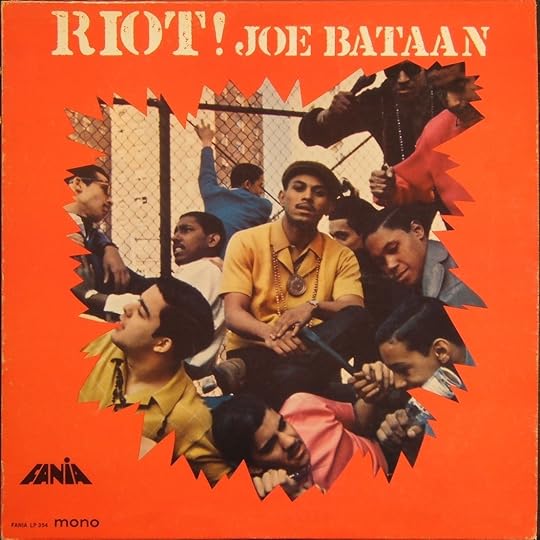

In 1966, Fania signed singer and bandleader Joe Bataan at Harlem’s Boricua Theater. Bataan went on to record numerous hits for the label, most of which were categorized as part of the emerging boogaloo trend, though Bataan, in a phone conversation, said he prefers to call his records Latin soul. Of African American and Filipino descent, Bataan is native of Spanish Harlem, El Barrio, the heart of the U.S. Puerto Rican community; he learned music by sneaking into Saint Cecilia’s Church on East 106th Street and practicing piano by night. He recognizes that his joining the label signifies Fania’s larger strategy, as his music “broadened their audience,” getting them airplay on radio stations that specialized in Latin music as well as the stations cast as more generically American.

In 1966, Fania signed singer and bandleader Joe Bataan at Harlem’s Boricua Theater. Bataan went on to record numerous hits for the label, most of which were categorized as part of the emerging boogaloo trend, though Bataan, in a phone conversation, said he prefers to call his records Latin soul. Of African American and Filipino descent, Bataan is native of Spanish Harlem, El Barrio, the heart of the U.S. Puerto Rican community; he learned music by sneaking into Saint Cecilia’s Church on East 106th Street and practicing piano by night. He recognizes that his joining the label signifies Fania’s larger strategy, as his music “broadened their audience,” getting them airplay on radio stations that specialized in Latin music as well as the stations cast as more generically American.

Fania’s motivations here may have been commercial, but they mirror what the historian Juan Flores calls “the social function of boogaloo”: as linking “neighbors and coworkers, African Americans and Puerto Ricans,” and as a “meeting place between Puerto Ricans and Blacks, and, by extension, between Latin music and the culture of the United States.” Flores alludes to Harlem geography—the adjacency of El Barrio to the African American neighborhoods of Central Harlem—as well as to the overlapping social issues confronting both ethnic groups that animated 1960s Boricua culture. Piri Thomas’s 1967 memoir Down These Mean Streets, captures the moment lucidly. Set in El Barrio, its dark-skinned protagonist fixates on his identity not just as a Boricua in New York but specifically in relation to his African American peers.

While Thomas represents a negotiation of Nuyorican and African American cultures, boogaloo performs it, and Bataan may be its embodiment. Bataan had a remarkable run at Fania, earning the informal epithet, “King of Latin Soul.” By 1969, though, he felt the label‘s focus shifting. Soon, ownership wasn’t interested in boogaloo at all; in its view, nobody was. It was time to make way for a new sound, the style eventually known as salsa.

Sanabria likes to say that boogaloo wasn’t killed, it was murdered: pushed aside by promoters, radio stations, and yes, Fania. (He promises to address this in a forthcoming memoir.) The accusation is echoed in interviews reported by Flores. But Fania’s longtime executive vice president Harvey Averne—who, as producer and musician, himself made popular boogaloo records—told me that the very notion that a record label would intentionally kill off a chance at profits is absurd. Alex Masucci, Jerry’s brother and another Fania executive, supports Averne’s claim.

There’s a case to be made that the shift was inevitable. Boogaloo faded along with the historical forces that had driven it. Salsa arrived and thrived at a time when Miguel Algarín and Miguel Piñero, poets of the Nuyorican school, started the Nuyorican Poets’ Café, and when the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican militant nationalist group, conducted direct actions in New York. To oversimplify: if boogaloo is cross-cultural, integrationist music, a product of the utopian sixties, then salsa is identity politics music, music to reaffirm the specificity of cultural heritage. The late ethnomusicologist Lisa Waxer called the genre “a potent emblem of Puerto Rican identity.” Salsa, unlike boogaloo, is meant to sound not like a meeting point between Afro-Caribbean music and other styles, but like a compressed expression of Latino experience. Classic salsa records, such as those by Colón, incorporate folk forms such as the Puerto Rican bomba and Panamanian murga. The lyrics, in Spanish, are imbued with a political imperative and ethnic specificity rarely found in boogaloo. Consider an iconic production, the Fania All-Stars concert LP and film Our Latin Thing (Nuestra Cosa). The possessive adjectives in the title—and the implied superfluousness of including “Latin” in the Spanish title—communicate the shift from the conceptual expansiveness underlying boogaloo to a more concentric approach.

There’s a case to be made that the shift was inevitable. Boogaloo faded along with the historical forces that had driven it. Salsa arrived and thrived at a time when Miguel Algarín and Miguel Piñero, poets of the Nuyorican school, started the Nuyorican Poets’ Café, and when the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican militant nationalist group, conducted direct actions in New York. To oversimplify: if boogaloo is cross-cultural, integrationist music, a product of the utopian sixties, then salsa is identity politics music, music to reaffirm the specificity of cultural heritage. The late ethnomusicologist Lisa Waxer called the genre “a potent emblem of Puerto Rican identity.” Salsa, unlike boogaloo, is meant to sound not like a meeting point between Afro-Caribbean music and other styles, but like a compressed expression of Latino experience. Classic salsa records, such as those by Colón, incorporate folk forms such as the Puerto Rican bomba and Panamanian murga. The lyrics, in Spanish, are imbued with a political imperative and ethnic specificity rarely found in boogaloo. Consider an iconic production, the Fania All-Stars concert LP and film Our Latin Thing (Nuestra Cosa). The possessive adjectives in the title—and the implied superfluousness of including “Latin” in the Spanish title—communicate the shift from the conceptual expansiveness underlying boogaloo to a more concentric approach.

Our Latin Thing does not feature Bataan. Despite having been one of the best-selling artists on the label, by the seventies Bataan had begun to feel “out of the limelight” as Fania focused energy on its Latino and Latina stars. These days, he’s happy to be re-affiliating with the label—he played the anniversary shows this summer in New York and California—which is under different ownership. Fania has in recent years been digitizing and reissuing its catalog, curating its legacy.

Boogaloo has crept back in, its return is a tribute to a DJ culture that helped to rediscover it, making crate-digging a way to engage with history, and to the omnivorousness of music culture in the age of the web. Salsa has stepped aside, the zeitgeist that elevated it long since evaporated, inevitably, its urgency and edge dulled in time. The Fania die-hards dancing up front still respond to that history; there’s room enough now for everyone.

Jonathan Goldman is an associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology, Manhattan. He is the author of Modernism Is the Literature of Celebrity and has contributed to The Millions and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

“The Life-World of the Occupation,” and Other News

The Nobel Foundation’s announcement this morning.

Just in case you haven’t heard: the French writer Patrick Modiano has won the Nobel Prize in Literature. His work evokes “the most ungraspable human destinies,” the Swedish Academy says. Apologies to the many runners up whose work evokes only the second most ungraspable human destinies.

Such as, oh, say, Philip Roth: “For years, the story goes, Roth would actually make the trip into New York to wait in his agents’ office for the call, a rough publicity schedule ready to be printed and activated. There he would sit, in a meeting room presumably prepared with refreshments, and at the end of the day, make the long, sad trip back to Connecticut.”

“There’s been a trend, in recent years, of novels based on the biographies of novelists. If some readers might recoil from the genre, the success of writers such as Colm Tóibín (who novelized the life of Henry James) and David Lodge (who also wrote a fictional account of James, as well as of H. G. Wells) suggest that a fictionalized life can revivify even the most heavily biographized writers—or at least those from the turn of the nineteenth century.”

Newly discovered Indonesian cave paintings, some forty thousand years old, suggest “a new view about modern human origins, about when we became cognitively modern.”

Pong, the video game that launched an entire industry, was first manufactured in an abandoned roller rink: “The Pong games were put together not on an assembly line but in the middle of the floor, with young workers ambling up to stick in the various components.

October 8, 2014

They Can’t Take That Away from Me

On this, the eve of the announcement of this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature, the Swedish Academy seems so furtive, so inscrutable. The suspense is palpable. Bookies are collecting bets; laureled authors around the globe are making steeples of their hands, entertaining their wildest fantasies. But if you want a quick and easy way to dispel the mythos, to lend a touch of levity to the pomp and circumstance of this nervous hour, just spend a few minutes with the Nobel’s Lord of the Flies game.

It is heinously unfun.

Really. Endodontic surgery is more fun than this game.

In its first stage, you match certain quotations and objects from the novel (glasses, bananas, a pig’s head on a pike) to their respective characters. From there, you’re invited to do more matching, this time pairing objects to themes (“Law and Order,” “Hope and Rescue”) that are mounted to palm trees. But wait—wait—what’s that theme there on the right?

Look, I know it’s pedantic, but at the moment it’s all we’ve got—a typo, a typographical error, disseminated by the offices of the highest literary prize in the land. A sign of fallibility from these infallible Swedes!

May it offer some succor to those writers perennially rumored to be Nobel front-runners—all those who are passed over, year after gnomic Swedish year. I may never join that banquet in Stockholm, your Philip Roths and Thomas Pynchons can say, but at least I can spell supervision.

The Will to Believe

Sitting in on the 2014 Objectivist Conference in Las Vegas.

The Venetian. Photo: Dietmar Rabich

Even on a Monday morning at eight A.M.—an hour ripe for sober reckoning—the greatest lie of Las Vegas endures undiminished: if you keep playing, you’ll eventually beat the house. As I strolled through the Venetian, I saw the familiar ring of mostly young men crowding the aprons of a long line of craps tables. If any moment in Vegas should lend itself to second thoughts for these men, it would’ve been this one, the morning after a boozy weekend of debauchery. Yet the only concession to the occasion were the mimosas hanging pendulously over the Pass Line.

I was late for a different sort of spectacle, so I didn’t stop to watch. The Venetian, by some measurements the largest hotel in the world, had set aside a tranche of its 289 “meeting rooms” for the annual summer conference of the Ayn Rand Institute, an organization founded in 1985, a few years after the death of its namesake, with the express mission of fostering “a growing awareness, understanding, and acceptance of Ayn Rand’s philosophy.”

Open conferences are admirably egalitarian, which makes them something of an awkward format for discussing Objectivism, the name Rand choose for her canon of unalloyed elitism. “The man at the top of the intellectual pyramid contributes the most to all those below him, but gets nothing except his material payment, receiving no intellectual bonus from others to add to the value of his time,” her avatar, John Galt, declares in Atlas Shrugged. Meanwhile, “the man at the bottom who, left to himself, would starve in his hopeless ineptitude, contributes nothing to those above him, but receives the bonus of all of their brains.”

One need not be an honors geometry student to understand where on this pyramid most of us must fall. Throughout her writings, which began with allegorical novels and evolved into a miscellany of short works—speeches, essays, newsletters, and even, for one year, a weekly column for the Los Angeles Times—Rand was an evangelist for an aristocracy of talents. She characterized her aesthetics as “a crusade to glorify man’s existence” and the essence of her philosophy as “the concept of man as a heroic being,” descriptions which, if they mean anything, would lead one to believe an assembly of her acolytes might resemble a cross between a meeting of Phi Beta Kappa and an afternoon among the bodybuilders at Venice Beach.

I wondered as much as I wound my way through the gilded alleys of the cavernous conference center. A floor beneath my destination, I passed the abandoned belvedere of the Martial Arts Industry Association, one of the many groups with scheduled summits that day. Later on, it would provide the only sighting of aggressively muscled men, who were conspicuously lacking at the Objectivist Conference—or OCON, the favored shorthand for attendees.

At first glance, they were an unassuming lot, whose sleepy eyes and towering lattes suggested they were as susceptible to the seductions of Sin City as most anyone else. They were a little older than I had expected and, more surprising still, there weren’t very many of them, eighty perhaps for the first session, an acroamatic overview of Ayn Rand’s philosophy. More arrived as the day progressed, but not enough to overcome the initial impression of a room full of empty seats, and not nearly enough for an interloper to feel anonymous in the least.

“Is this your first OCON?” a well-appointed woman with two cell phones asked me shortly before an afternoon session. The question was clearly rhetorical, coming as it did from someone who made it plain to me that she looked forward to the conference in much the same way we all anticipate certain events that embellish our identities. She wasn’t alone. One speaker shared that he had about twelve people he considered family. “Some are in this room right now,” he said, “and there’s only one of them biologically related.”

Such moments make me hesitant to call the conference participants “true believers,” not so much because the term is misapplied—given that one panel was titled “Objectivism Is Radical,” I suspect most of them would embrace it—but because it fails to capture what struck me about them. They seemed less like ideologues impatient for Galt’s Gulch than the graying registrants of a reactionary class reunion.

The effect was one that is common to any routine gathering that riffles a creedal code. The revealed word is best left unspoken, for demystification comes cheap: to the grizzled comrade sipping cold coffee between plenary sessions of the Sixth Congress of the Communist International, even Capital must seem a little less enchanting. The old villains remain—and at OCON, the welfare state, Obama, and liberal intellectuals all came in for a drubbing. But neither they, nor the cause they threaten, have the same sense of urgency. Familiarity may breed contempt, but it also breeds complacency.

And that’s why the first timers, perhaps a quarter of the crowd, were the more intriguing group to watch. Some of them were the high-school and college kids the Ayn Rand Institute determinedly cultivates, but others seemed to have recently “found” Rand’s work. For them, The Romantic Manifesto, The Fountainhead, and especially Atlas Shrugged still had the dazzling immediacy of a message that is extraordinary and half explained. They mobbed the microphone at the end of each session, eager to ask questions that inevitably involved a “coming to grips” with Rand’s philosophy.

Some were simply matters of implementation. At an education panel, a slight young man recounted the indignity of having to write a paper on Gravity’s Rainbow. He quickly determined that Thomas Pynchon was unworthy of his time—“he has no plot, there is no theme, there is no reasoning”—but when he shared his conclusion, he found himself sent to the principal’s office. There, he had a minor epiphany: what is right and what is expedient aren’t necessarily one and the same. Ambitious to get into a good college, he simply had to know: What would Rand do?

Some variation of that question was most common among the neophytes, but the more compelling inquiry came from those who ached because they already knew the answer. At the final session I attended, “How to Be an Impassioned Valuer,” a man wanted to know what you should do if you had lost the time to pursue the things you value. The question wasn’t exactly well thought out, and it seemed a little strange coming from someone who looked to be in his thirties, but everyone knew what he was getting at. The problem was not a matter of time but competence. What if you knew what you wanted to accomplish with your life, but you also knew in your heart of hearts that no matter how long you applied yourself, no matter how hard you tried, you could never do it, not in any way that would ever seem exceptional, not to you and certainly not to Ayn Rand? Could you live with yourself consistent with an elitist philosophy?

You couldn’t. That’s the honest answer, which is why Objectivism is the most American of philosophies. Its appeal, like that of Las Vegas, ultimately relies on the most irresistible self-deception of them all: You are never not exceptional. Only not yet.

John Paul Rollert is a writer in Chicago. His work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Boston Review, and the New York Times.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers