The Paris Review's Blog, page 657

October 3, 2014

Staff Picks: Thirteen Days, One Hundred Brothers, Five Cars

“We build excitement“: a still from an oddly captivating old Pontiac ad.

The latest issue of Guernica includes Richard Price’s tragic history of New York public housing; he begins in a state of noble objectivity and then goes brilliantly, subjectively off the rails, telling of his own childhood in the north Bronx’s Parkside Houses: “The women played gin rummy, mahjong, coming to each other’s apartments in quilted housecoats and curlers, clutching vinyl-covered packs of Newports and Winstons. Many a kid, myself included, fell asleep to the clack of ivory tiles or the riffle of cards, nodded off to a non-stop soundtrack of laughter, blue language, and hacking coughs coming from the game in the dinette, our bedrooms comfortingly wreathed in cigarette smoke.” From here, he tells what should be a familiar story uniquely well—how the projects, one of the early triumphs of city governance, went from having a waiting list of 160,000 families to serving as a symbol of “the truly hopeless and disenfranchised.” —Dan Piepenbring

Editors are often asked to describe, in a word or two, what kind of fiction they like. I’ve never known what to say—but “low concept” would be a start. The less describable a novel is, the less it depends on a premise, the more apt I am to like it. This makes it hard for me to recommend Donald Antrim’s 1997 novel The Hundred Brothers. It really is about one hundred brothers (Phil, Angus, Walter, Virgil, Barry, Seamus, Arthur, and ninety-three more) who gather in the vast library of a crumbling estate to work out their sibling rivalries and put their father’s memory to rest. The strange thing about the book, or really, one of the many strange things about it, is how cinematic it is. It’s incredible that dozens of middle-aged white guys making small talk and waiting for cocktails could leap so vividly to life, in just two hundred pages, or descend so concretely into mayhem. —Lorin Stein

Once this unseasonably warm weather comes to an end, I look forward to using my oven again. Treacle tart in particular holds a special place in my heart, as it was the first dessert I ever baked—which is fitting, because “Treacle,” by the Liverpudlian Paul Farley, is the first poem in recent memory to stick solidly in my mind. Farley has gained a steady following in the UK but remains virtually unknown in America, where only one volume of his work has been published. This will come as a surprise when you hear him read this haunting poem. His appropriately chewy diction leaves me awed and disturbed; he describes that chilling moment when you “lever the lid” of a tin of treacle and “it opens with a sigh / and you’re face-to-face with history.” —Charles Shafaieh

I’m often suspicious of political nonfiction, which seems to me the literary equivalent of a CPA: nerdy, unglamorous, and gray. But Lawrence Wright’s new book, Thirteen Days in September, is neither dull nor dour; it’s just good. It re-creates a 1978 summit at Camp David led by Jimmy Carter. Over the course of, yes, thirteen days, three disparate politicians—Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, and Carter himself—attempt diplomacy and an understanding. It’s a complicated story to tell, but Wright’s prose, always lucid, transforms a tangled history into a compelling narrative. —Kate Gill

After a long, hard week at the office, here’s how I like to relax: by watching car commercials from the eighties. The jingles! The jingoism! The digital speedometers! Thirty years down the line, it should be easy to cast a cold eye on such graceless pap, with its hokey slogans and its relentless sincerity. “We build excitement,” says the Pontiac LeMans; the Plymouth Voyager tells us that “the pride is back”; the Chrysler Laser knows that “the competition is good. We had to be better.” What is it about these ads, then, that I find so peculiarly effective? Why, for all my condescending laughter, do I come away sort of wanting a Chrysler Laser? There’s a lesson here about irony, nostalgia, and seduction in advertising, but I can’t put my finger on it. I only know that “the new Dodge Shadow is going to cast a giant shadow across America.” —D.P.

Nevermore

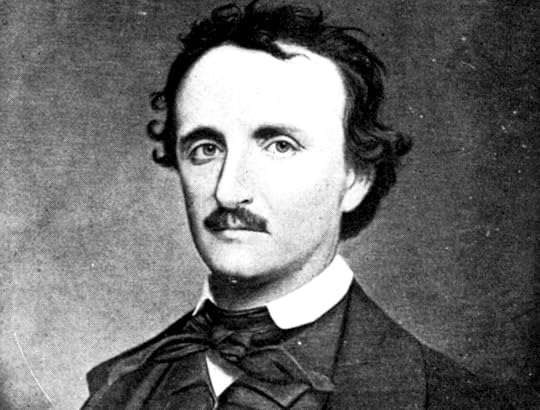

The frontispiece from Edgar Allan Poe: A Centenary Tribute, 1910.

On October 3, 1849, a delirious Edgar Allan Poe was found in a Baltimore ditch dressed in clothes that were, reportedly, not his own. He died four days later at Washington Medical College. There are numerous theories, but the exact cause of death remains a mystery, as does his presence in the ditch.

If Poe interests you, you wish to commemorate him, and you happen to be in New York, be sure to go to the Grolier Club and catch the public exhibition “Evermore: The Persistence of Poe,” which consists of the extensive Edgar Allan Poe Collection of Susan Jaffe Tane. In addition to manuscripts, first editions, personal effects, and letters belonging to the writer, the show has a section devoted to Poe’s portrayals in pop culture, which include everything from John Cusack’s unfortunate turn in 2012’s The Raven to the Unemployed Philosophers Guild’s ubiquitous Poe doll. Particularly arresting is a poster for 1944’s The Loves of Edgar Allan Poe, a film that was unknown to me. But I rushed home to remedy that at once, and, luckily for all of us, the whole thing’s available on YouTube:

It’s something to see. Maybe not literally—at least, not if you’re a stickler for historical accuracy or cinematic excellence. Despite cameos by both Thomas Jefferson and Charles Dickens, it cannot be called a rigorous scholarly work. Because of the basic contours of the writer’s life, it’s hard to make the story anything but sad; he does, after all, end up impoverished and dead at forty.

But the focus, as the title indicates, is definitely on romance. Unpleasant biographical details—his hardscrabble upbringing, his mother’s death, his debts—are dealt with via turgid voice-over narration; most of the action is reserved for affairs of the heart. First we see Edgar’s youthful infatuation with Elmira Royster, who spurns him and acts as a muse. When we meet Virginia Clemm, it is in the comely form of Linda Darnell, who, at twenty-one, is approximately eight years too old for the role.

Poe’s fervent worship of the various women in his life is legendary; no study of his work or biography can ignore it. And certainly, his wife’s premature death and his own descent into grief are dramatic enough for any movie. Like most of the details of Poe’s life, those about his marriage are hazy. Some biographers claim his relationship with his wife was platonic; others cite reports that they merely waited several years before consummating their marriage because of Virginia’s youth.

What is documented is the couple’s mutual devotion; as Poe’s onetime boss, the publisher George Rex Graham, wrote, “His love for his wife was a sort of rapturous worship of the spirit of beauty,” and her idealized image appears again and again in his later work. It’s also true that Poe’s alcoholism certainly worsened with the illness and death of his Virginia, and he lived only another two years—despite throwing himself into several relationships and even one short-lived engagement. But the marriage was not rosy, in all: in real life, at the height of his fame, Poe was linked to both the writers Frances Sargent Osgood and Elizabeth F. Ellet; the result was a well-publicized scandal. Whatever the facts of the case—they’re murky—it was apparently devastating to Virginia, who’s rumored to have brought up Ellet on her deathbed, referring to her as her murderer.

All that would have made for a really good movie, but it’s not the story The Loves of Edgar Allan Poe attempts to tell. As that film has it, Virginia’s death was serene, with welling strings. Poe dies about five minutes later, sans rebound romances, after some admirers find him in a tavern. The ditch does not appear, credited or otherwise. Instead, we see Poe on his deathbed, intoning, “Virginia, dearer to me than life … you are not wrong who deem that my days have been a dream … all that we see or seem is but a dream in a dream.”

In fact, Poe’s last words were reported variously: “Lord help my poor soul,” he said according to some. According to others: “Reynolds.”

Nothing Happened: An Interview with Joseph O’Neill

Photo courtesy of the author

The narrator of Joseph O’Neill’s new novel, The Dog, decides to move to Dubai. Transitional places make more sense to him than those in which “everything has been built and all that remains is the business of being in buildings”. He sees his own life, in the aftermath of a recently disintegrated relationship, as somehow “posthumous” and shameful. And meanwhile his legal training, instead of arming his intellect, merely alerts him to the inadequacies of the language he’s forced to use. “Lost in a fantastic vigilance of ambiguity, obscurity, and import,” caged in by the feeling that “the very project of making sense [is] being mocked”, he drafts endless disclaimers and other corporate documents that he only slenderly understands. His new apartment tower is called The Situation. His preferred spa is called Unique. But even recreation is an exercise in compromise—“there’s more than one Unique.”

Javier Marías, paraphrasing Faulkner, once told an interviewer that “when you strike a match in a dark wilderness it is not in order to see anything better lighted, but just in order to see how much more darkness there is around.” The Dog isn’t much interested in bright epiphanies. Instead it shows the extent of one man’s ignorance—his helplessness in a foreign world. The evocative sentences that helped to win O’Neill’s previous novel, Netherland, the 2009 PEN/ Faulkner Award and a wide readership, are largely absent here. With its deadpan existentialism and playful corporate-speak, The Dog is perhaps closer to a book like Joseph Heller’s Something Happened. It is bleakly, unexpectedly funny.

I met O’Neill in Manhattan on an afternoon in mid-September. We talked about the fact that Netherland “very nearly didn’t get published at all,” the relationship between his work and that of Louis C.K., and why he is “deeply uninterested in the chattiness you get in so many contemporary novels.”

It’s been mentioned by various reviewers that The Dog is a very different book to Netherland, at least in its tone. What sort of sentences did you find yourself looking for as you sat down to write, and what kinds of sentences did you find yourself striking out?

Generally, I want sentences that are both conscientious and surprising. For me, plot happens most of all at the level of the sentence. As I reader, I want to start a sentence and then be surprised by what happens to it, or intelligently happens. To be surprised by the conscientious movement of emotion and attention over the course of the sentence. I used to write poetry, and I think good poetry does that—captures a movement of intelligence. Still more generally, I want a verbal landscape that’s unusual—that I haven’t read a million times before, and that isn’t easily replicable in other forms. This approach animated the writing of Netherland.

In The Dog, my main character is a theorist—he is disposed toward theorizing and rationalizing, as well as to deep emotion, and is only occasionally given to recollection. To my mind, this makes him a comically urgent character—a man who is constantly caught short by this thoughts, who constantly needs to take a mental leak. That being the case, it wouldn’t have made sense to reuse the highly particular, contemplative voice of Netherland.

I’m not interested in writing stuff that’s indistinguishable from other stuff. I’m trying to avoid that deathly sense that here’s something you’ve read before, but with different characters, or with one situation replaced with another. I’m also deeply uninterested in the chattiness you get in so many contemporary novels.

What are you thinking of when you say chattiness?

That kind of conversational tone that you see in so much fiction. The banal and treacherous lucidity that’s underpinned by a bogus, consumeristic egalitarianism, which cannot tolerate the idea that good writing might not instantly and cost-effectively yield its full significance, and might in fact make one feel in some sense beneath the work … I mean, when I read I want to feel that I’m beneath the work. That’s what I look for in art. I want it to be my superior.

When I was writing The Dog, I was reading a lot of philosophical prose, which can be humbling and dense and strange—the opposite of a page-turner, you could say. As a reader, I have almost no desire whatsoever to turn the page. I would rather stay right where I am, on the page I’m reading, and stick with what’s there. Stay with the text and joyfully see how it works, word by word, and absorb the language and what’s going on there, and only turn the page as a last resort, when the language runs out. I wanted The Dog to capture some of the stillness and depth of philosophical texts. For me, there’s enormous pleasure and excitement in that.

Both Netherland and The Dog are written in the first person. In the last decade, when you’ve used the third person in your writing it has tended to be on smaller canvases—your short stories.

I just don’t think I’ve cracked the third person. Haven’t come close to it. There are these maestros like Flannery O’Connor and Muriel Spark who situate the point of view in some dimension of objectivity that is their own. Bellow is a third-person master too, though his trick is to write in the third person as if it’s the first person—to appoint a protagonist and then get very, very close to his thoughts and feelings. All that said, it’s not just a question of my technical helplessness. I have philosophical doubts about writing in the third person. It’s no coincidence, I think, that so many of the novels I love best have, at their center, a kind of turbulent consciousness around which everything else revolves. Both Netherland and The Dog are like that—there’s a central subjectivity to them—and a first person voice feels to me like the right way to explore a consciousness of that kind. First person offers, among other things, immediacy, which I value very highly.

My feeling is that I just get to write in the first person. The reader understands that form of address and understands its infirmities, and understands that it is a productive misrepresentation of the character’s inner state. Everyone gets this, just as they get and accept a close-up in a film and don’t start shouting that the character’s head is way too big or her voice is way too loud. We’re talking about formal shortcuts, basically. The first person is the shortest of shortcuts to an elusive element of the real, a person’s unspoken life, access to which is unavailable elsewhere in art.

At the start of the book, in a striking passage, the narrator talks about scuba diving in Dubai. As the novel moved on, I felt at times like the relationship of reader to narrator in your novel was that of a diving buddy to another diver. The narrator is this oblique presence whose confusing signals we read—at first with amusement, and then with a mounting sense of unease. We realize, slowly, that he’s in trouble down there …

He is in trouble, you’re right. But aren’t we all in trouble? Aren’t you in trouble too?

Initially, I envisaged this whole book as taking place entirely underwater. That was my very first thought, before I began writing. I wanted that weird descriptive alienness that an underwater setting might involve: unknown entities, a fluid element, an inhuman space … Then I decided not to. It was too limiting, and also I don’t scuba dive and I’m too scared to try it. It would have been a nightmarish book—an even stranger novel than it is—if it had all been set underwater.

I’ve moved around so much and lived in so many different places that I don’t really belong to a particular place, and so I have little option but to seek out dramatic situations that I might have a chance of understanding. Hence Dubai: Dubai is an expat center.

Has the fact you’ve moved around so much in your life, living in so many different countries from childhood onward, been useful to your fiction in some way—that sense of not belonging?

Essential, I think. But it’s only now that I have some idea of how to make use of it in my fiction. Before Netherland, I didn’t know how to approach that sense of chronic displacement. It took me a while to realize it was a huge story, the sense of not belonging, as you put it—of pretty much never being in a position to say, These people and I are the same. You could write a thousand novels about it and it wouldn’t get old, because it’s such an essential part of what it is to be human—that idea of where, if anywhere, you fit in, in the so-called scheme of things. And how does the world work? A lot of novels might inform you about how a character gets on with his Auntie, but they won’t necessarily tell you where the characters stand in relation to the world. I’m interested in putting characters in places where the world order is changing, and changing in a particular way. The word globalization grunts into view, here, along with post-nationalism, another brute.

Essential, I think. But it’s only now that I have some idea of how to make use of it in my fiction. Before Netherland, I didn’t know how to approach that sense of chronic displacement. It took me a while to realize it was a huge story, the sense of not belonging, as you put it—of pretty much never being in a position to say, These people and I are the same. You could write a thousand novels about it and it wouldn’t get old, because it’s such an essential part of what it is to be human—that idea of where, if anywhere, you fit in, in the so-called scheme of things. And how does the world work? A lot of novels might inform you about how a character gets on with his Auntie, but they won’t necessarily tell you where the characters stand in relation to the world. I’m interested in putting characters in places where the world order is changing, and changing in a particular way. The word globalization grunts into view, here, along with post-nationalism, another brute.

It’s there in Netherland from the beginning, incidentally. Hans reads about a group of tribespeople who’ve emerged from the Amazon forest into a place they don’t even know is Colombia. They haven’t even heard of Colombia, or even Columbus. So the question of pre-national or non-national identities is raised at the start of the book, and the book ends with these moments in which the world appears, the Googling protagonist, as a merely physical, or post-national, entity. I feel that Dubai, in this novel, is the next iteration of my interest in those ideas. It’s a place where societal participation or belonging is a very largely a question of denizenship rather than citizenship. Only around ten percent of the population are natives. The rest belong there so long as they are permitted to work there.

I read somewhere that you admire Updike’s book Self-Consciousness, and when I was looking through my copy of that book I found this quote—“For many men, work is the effective religion, a ritual occupation and inflexible orientation which permits them to imagine that the problem of their personal death has been solved …” Is there something applicable to the narrator of The Dog in that quote?

My narrator has a very unusual job. He doesn’t really have any colleagues. He has one underling who, due to Dubai laws and the underling’s non-nationality, doesn’t even rise to the status of an employee. The narrator also has this rather paradoxical relationship with the corporate entity he works for—he’s the man who signs the papers on behalf of this rich family’s trust, but at the same time he is constantly trying to limit his personal liability in case the company is involved in wrongdoing. But despite his efforts, he feels unprotected by the corporate veil, and he’s terrified, because there comes a point when, as the corporate officer, his actions are indistinguishable from those of the company he works for. He is the biological manifestation of the corporation. I think, like many people, the narrator of The Dog feels, in his work life, subject to a terrible indeterminacy. Work, for him, is really a question of being frightened. He’s not even sure he really knows what his job is, beyond its humiliations and shame.

The break-up of his relationship is clearly painful to him, but he seems to feel a shame that is far more general and amorphous than that. An unspecified shame at who he is.

It does seem to me, as it has seemed to countless others, that there’s a very ancient and powerful condition, let’s call it shame, that we all, as human beings, have to deal with in some way or another—most obviously by covering ourselves up. The Adam and Eve myth. Nakedness. Being uncovered. It leads to shame, and by our shame we achieve our humanity. It’s as if humanity is shame. And I would agree with you, the shame experienced by the narrator of The Dog doesn’t seem to come only from his former relationship or his conduct in it. We all have those moments, moments that—this is a very English phrase, isn’t it?—we’re not very proud of. His shame would seem to be bigger than that. He’s sensitive to an idea that it’s shameful simply to be who he is, a person who needs to go to work, to take orders and sign documents, interact with others, take a shit … I feel he’s related to the character in Louie—Louie. Louie, if you’ve watched the recent episodes, isn’t that funny anymore. It’s almost too dark. It has become a deliberately excruciating comedy of ethics.

I hadn’t thought of Louie. But I thought at times of Joseph Heller’s Something Happened, that dark portrait of a man on the edge, misunderstood at work and at home—the bleak comedy of that.

I’m joyfully surprised you mention Something Happened. Do people still read that book, do you think? Would it even get published today? It would certainly get panned. There is eventually a reveal in Something Happened—something does happen—but not much. It’s more a past tense question in that book. What has happened to this guy to make him who he is? I think there’s a sense in which The Dog, like Something Happened, traces the consequences of a crime that cannot be fully identified. Why’s he in the doghouse? Why does he feel like a dog? He doesn’t even know.

The books you wrote and published before Netherland didn’t receive much attention. Netherland broke out in a spectacular way. With this book things seem to be going well—it’s been longlisted for the Booker Prize, after all—but the reviews have been more mixed. Have your views of what it means to be a published writer changed over time?

Publication is almost certainly a punishment for having written a book. Netherland was an exception. The right reviewers discovered the book at the right time. There was a lot of luck involved in that. The Dog hasn’t been quite so lucky, although I’ve got to say that it’s had its share of breaks.

When I was writing Netherland, all I knew was that I was giving it my best shot. If I assumed anything it was that, as with my previous books, it wouldn’t reach any readers at all. Which nearly turned out to be the case. The manuscript did the rounds for ages and was rejected by everybody. Eventually we found one editor in England who would take it, and one here in America. That’s all you need. It very nearly didn’t get published at all. My previous books had gone out of print at that point. Then my luck changed. It could change again. That’s the way it is. My job is to keep writing—isn’t it?

Jonathan Lee's new novel, High Dive, will be published next year.

From the Land of Pleasant Living, and Other News

A Baltimore icon slips into Russian hands.

Remembering John Berryman, whose centenary is later this month: “Berryman has not been forgotten, but his gnomic revelations have less force than they used to. His drinking and womanizing, his unsoothable anguish, seem less the stuff of heroism than of mutinous neurotransmitters. I can all too easily imagine him today, sitting at a seminar table in Palo Alto or Iowa City, buoyed by a decent dose of Wellbutrin, listening as some regular contributor to the Northwestern Maine Quarterly Review piously instructs impious John to simmer down, center himself, drop the unceasing allusions to Shakespeare, find his voice and tell us how he really feels.”

“As well as categorizing novels as well or poorly written, popular or unpopular, one could also, and perhaps more usefully, distinguish those that become part of the conversation, and those that do not. Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections became part of the national conversation; Lydia Davis’s short stories, for all their brilliance, did not … John Updike’s Terrorist was arguably his least talked-about novel … But how does a book enter the conversation today?”

A good problem to have: “I am in the slightly embarrassing position where I write poems saying I am about to die and I don’t.”

An 1894 map by the New York Tenement-House Committee divides the city by nationality. But you won’t find Scotch, English, Welsh, Scandinavian, and Canadian New Yorkers on the map, because they were, according to its creator, “in small numbers and perhaps less foreign than the others.”

The Orioles are in the playoffs, which means Baltimoreans are swilling profligate amounts of Natty Boh, the greatest bad beer in the world and one of the city’s most cherished brands—it dates back to 1885. (At least one Baltimorean would drink a can right now, even though it’s nine-thirty A.M. and he’s in New York.) The only problem? “National Bohemian hasn’t been locally owned since the nineteen-seventies, and it hasn’t been brewed in Maryland in more than a decade … Last month, it was announced that the brand’s owner, Pabst, is being purchased by the Russian beverage company Oasis.” Say it ain’t Boh.

October 2, 2014

Just Slap Something on It

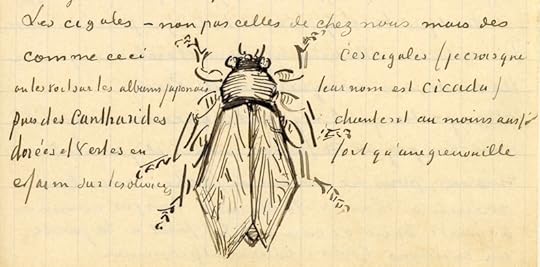

A sketch of a cicada in a van Gogh letter from July 1888.

Next month will come Ever Yours: The Essential Letters of Vincent van Gogh, which runs to nearly eight hundred pages and is frequently more absorbing, expansive, and instructive than a collection of letters ought to be. (He seldom seems to miss the forest for the trees, you could say.) As I thumbed through it, a passage leaped out at me from exactly 130 years ago—a letter van Gogh wrote to his younger brother, Theo, on October 2, 1884. It’s both Grade A existential grousing—were it not for the (faintly) uplifting conclusion, I could’ve believed that Thomas Bernhard wrote it—and, it seems to me, pretty sound advice.

Just slap something on it when you see a blank canvas staring at you with a sort of imbecility.

You don’t know how paralyzing it is, that stare from a blank canvas that says to the painter you can’t do anything. The canvas has an idiotic stare, and mesmerizes some painters so that they turn into idiots themselves.

Many painters are afraid of the blank canvas, but the blank canvas IS AFRAID of the truly passionate painter who dares—and who has once broken the spell of ‘you can’t.’

Life itself likewise always turns towards one an infinitely meaningless, discouraging, dispiriting blank side on which there is nothing, any more than on a blank canvas.

But however meaningless and vain, however dead life appears, the man of faith, of energy, of warmth, and who knows something, doesn’t let himself be fobbed off like that. He steps in and does something, and hangs on to that, in short, breaks, ‘violates’—they say.

Let them talk, those cold theologians.

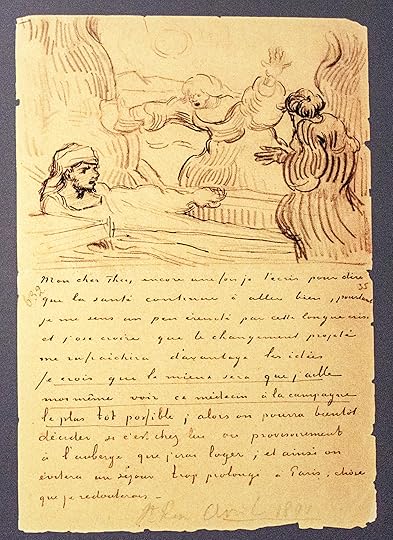

A letter of van Gogh’s from May 2, 1890.

Blank Verse

Erskine Nicol, Kept In.

It is not often in this day and age that something falls through the Web. And yet, today, National Poetry Day, I wanted to share with you the text of my favorite childhood poem and found myself completely stymied. Not a trace of it exists.

I even know the name of the poem—“The Call of the Child”—though I don’t recall the author. What I know for certain is that it was a little red-bound, tasseled pamphlet, probably dating from the first two decades of the twentieth century, keeping in mind that Jack London’s Call of the Wild was published in 1903. Okay, maybe calling it a “poem” is misleading—it was more a long piece of doggerel*.

“The Call of the Child” is the first-person lament of a baby who really, really has to pee. He complains about the urgency of his need, the pressure on his bladder, the indignity of wetting his pants and bed. He fantasizes about peeing with abandon, spraying fountains of urine wherever he wishes. At one point, he goes into a reverie, imagining a fantastic bed rigged up with a series of rubber hoses that lead directly from his penis down to some kind of basin, allowing him to joyfully wet the bed whenever he likes without discomfort or censure. Oh, and it’s all in rhyme.

I found this book the most hilarious, fascinating thing in existence. Part of my fascination may have derived from the fact that the toilet-training picture book Once Upon a Potty was banned in our house; my mother didn’t like the babyish euphemisms used for bodily functions. As such, it took on the forbidden lure of pornography, and I would covertly look at it whenever we entered the children’s section of a bookstore. I’m not sure how she felt about “The Call of the Child”; I only recall that I made my dad read it aloud to me over and over. In retrospect, I wonder whether the intended audience was rapacious kids or infantile adults. After all, in a world where everyone knew verse by heart, maybe its bastardized form—doggerel—seemed a lot more hilarious than it does today. In any event, I imagine a Freudian could have some fun with it, if he went in for fish in barrels. As a sociological document, it is noteworthy, too. As Joseph L. Zornado’s Inventing the Child: Culture, Ideology, and the Story of Childhood—and, more briefly, this informative Salon article—make clear, the early twentieth century was a dynamic period for conceptions of early childhood generally and toilet-training specifically; more indoor plumbing meant more flexibility. Whereas in 1900 it was not uncommon to tie a child as young as six months to a potty, by 1920 kids could, if not set their own timetable, at least wear a diaper slightly longer. (Regularity and schedules were still at a premium pre-Doctor Spock; the booming 1940s laxative industry and prune market are a testament to this.)

What is the purpose of poetry? To move? To entertain? To stimulate? To confound? To revolutionize? While it may not be a “great” poem, by any of these standards, “The Call of the Child” succeeds. Happy National Poetry Day. And if you know who the mystery scribe is, please let me know.

*Doggerel is one of the best words in the English language. The etymology derives from dog. Wikipedia is quick to remind us that “hip-hop lyrics have also explored the artful possibilities of doggerel.”

Under One Roof

Ludwig Bemelmans’s Paris bistro, La Colombe, combined two of his passions: art and innkeeping.

Ludwig Bemelmans's Woman with a Dog, a mural from the La Colombe restaurant.

“It was precisely what I had been looking for—a lovely house, half palace, half ruin, an old house covered partly with vine,” Ludwig Bemelmans wrote in his 1958 illustrated memoir, My Life in Art. In 1953, he’d bought the hôtel particulier that once belonged to La belle Ferronnière (mistress of François I) at 4 rue de la Colombe, in the shadow of Notre Dame. “It had a bistro on the ground floor frequented by clochards and a small garden in front in which people sat.”

He christened the bistro La Colombe and covered its walls with near life-size frescoes of café society—Bemelmans’s own Bemelmans Bar. But it was not to last.

“Fifty three was a marvelous year for him, and a terrible year at the same time,” explained Jane Bayard Curley, the curator of the New York Historical Society’s current exhibition, “Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans” (on view through October 19). “He was doing La Colombe, he was painting the murals for Aristotle Onassis, he was publishing his Caldecott Award–winning Madeline’s Rescue. So many good things were happening that year and then the wheels came off.”

* * *

According to My Life in Art, the story of La Colombe began with a clochard (a vagrant) Bemelmans saw from the window of his Rive Gauche apartment, fastidiously shaving on the bank of the Seine. Soon Bemelmans was leaving presents for the clochard—an old coat, some cigarettes—and the two became friends. The clochard, it turned out, had been a history teacher in a girls’ school.

“Oh, not what you think happened—God forbid!” the clochard declared to him. “It was just that I was in steady conflict with the director. The maniacal principal of this institute almost drove me to suicide. I had to leave or I would have killed him.”

Now free, the clochard offered Bemelmans his services. Bemelmans confessed that he’d been hoping to buy an old house to live and work in; could the clochard find such a place? That spring, he did: “When we get there, walk past it, but don’t go in yourself, for that would raise the price; I shall arrange everything.”

But this is embroidery. “The real story,” Bayard Curley told me, “was Bemelmans was in Paris, staying at the Ritz. Through his lawyer he met this young girl, Régine, and it was she who found La Colombe.”

From the sign for La Colombe.

The restaurant-studio, partly covered in vine, was as much an idyll for grown-ups as Madeline’s world was for children. “The life of an innkeeper is better than any other,” he wrote in Holiday magazine the year he bought La Colombe. “At intervals of several years this realization bothers me enough so that I put my paints away, cover up my typewriter and look for a door through which I can step back into my old profession.”

Bemelmans was born into a family of innkeepers. His uncle Hans owned hotels around the Austrian Tirol, where young Ludwig—known as lausbub, or rascal—was sent to learn his trade. In no time, Ludwig lived up to his nickname and Uncle Hans gave him an ultimatum: go to reform school or go to America. So Ludwig arrived in New York on New Year’s Eve 1914, armed with letters of introduction to the managers of the best hotels. Soon he was a busboy, later assistant banquet manager, at the old Ritz on Madison and Forty-sixth Street, surreptitiously sketching the over-fed patrons on the backs of hotel menus. Bemelmans later published his memories of life at the Ritz as Hotel Splendide, which was also serialized in The New Yorker. He slept in unoccupied hotel suites, painted in the ballroom, and bought an open, café au lait–colored Hispano-Suiza upholstered in leopard skin. (The car belonged to a marquis’s mistress staying at the hotel, who was decapitated while driving it.) Bemelmans hired Kalakobé, the hotel’s Senegalese dishwasher, as his chauffeur. But Kalakobé couldn’t drive—the two sat side by side in the open car.

As Bemelmans the writer-illustrator succeeded, Bemelmans the hotel employee diminished, but he never disappeared. In the decades to come, Bemelmans would decorate, or have a stake in, the Hapsburg House restaurant on Fifty-fifth Street, the Dove and Turtle Inn on Long Island, and the Carlyle Hotel bar that still bears his name.

“La Colombe, for me, was his dream come true,” Bayard Curley said. “It was his very own restaurant, his very own studio on top. It was like his dream of the perfect life. It had everything he wanted: his art and his innkeeping under one roof … in the middle of Paris.”

La Colombe was also a money pit. “The dear little old house, the poetic corner, turned into a cathedral-sized nightmare,” Bemelmans wrote. Centuries of dereliction had to be swept away and the Paris bureaucrats, not always disposed to American entrepreneurs, made impediments at every turn. When La Colombe finally opened, Bemelmans imagined le tout Paris arriving in period costume: La belle Ferronnière and François I, Héloïse and Abélard, Quasimodo and Esmeralda, ready for the party of the season. But there were no bathrooms. Bemelmans couldn’t secure the permits, so he hired a taxi—with one door labeled “Mesdames,” the other labeled “Messieurs”—to ferry the needful to and from nearby facilities.

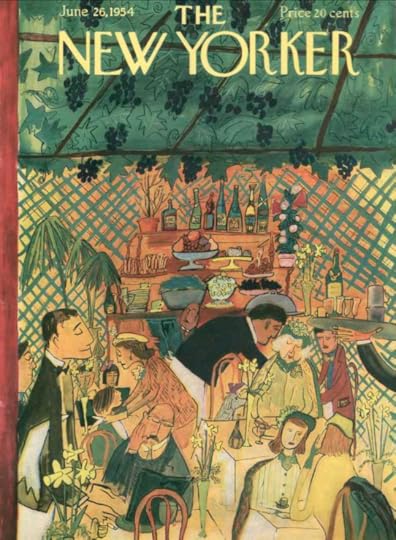

The scenes he painted on the walls mirrored life at La Colombe. Unlike the Carlyle frescoes—completed in 1947 in exchange for hotel room and board—which showed Madeline and tuxedoed camels lunching in Central Park, here Bemelmans recorded the people he had watched throughout his career. High-nosed waiters carried café chairs above the heads of their thronging customers, blasé dowagers drank white wine or verveine alone, chefs prepared steak tartare. If the Carlyle was New York à la Madeline, La Colombe was Paris à la Bemelmans. As an artist, his approach was also more mature. Instead of isolated, fantastic vignettes wandering across the walls, La Colombe showed a continuous field of action, a world one could, and would pay to, enter.

On June 26, 1954, The New Yorker ran one of Bemelmans’s many covers, using elements from his Colombe frescoes, but it was too late. Facing endless expenses, and no doubt his own extravagance, Bemelmans was forced to leave La Colombe after only a few months. It passed into the hands of Michel Valette, who ran it as a cabaret-restaurant until the mideighties. The building changed hands again and the frescoes were thought to be lost, until 2012, when Bayard Curley came across a private auction, offering five familiar wall panels and the original Colombe metal sign for sale. The Colombe frescoes entered the collection of the Ocean House hotel in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, and three panels have been lent to the Historical Society’s exhibition by the hotel owners, Charles and Deborah Royce.

On June 26, 1954, The New Yorker ran one of Bemelmans’s many covers, using elements from his Colombe frescoes, but it was too late. Facing endless expenses, and no doubt his own extravagance, Bemelmans was forced to leave La Colombe after only a few months. It passed into the hands of Michel Valette, who ran it as a cabaret-restaurant until the mideighties. The building changed hands again and the frescoes were thought to be lost, until 2012, when Bayard Curley came across a private auction, offering five familiar wall panels and the original Colombe metal sign for sale. The Colombe frescoes entered the collection of the Ocean House hotel in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, and three panels have been lent to the Historical Society’s exhibition by the hotel owners, Charles and Deborah Royce.

Last week a mother and daughter were going up the stairs to that exhibition, the last room of which is devoted to Bemelmans’s works for grown-ups: the Colombe frescoes, “Adieu to the Old Ritz,” and painted lamps from the Carlyle’s Bemelmans Bar.

“Let’s go see Madeline!” the mother said to the girl, who started skipping up the stairs, two at a time. An old man with a straw hat tilted at a rakish angle was just going down. “Forget Madeline,” he whispered. “Go see Bemelmans.”

Patrick Monahan is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to Vanity Fair.

Oh, Shit, There Are Robots in the Library, and Other News

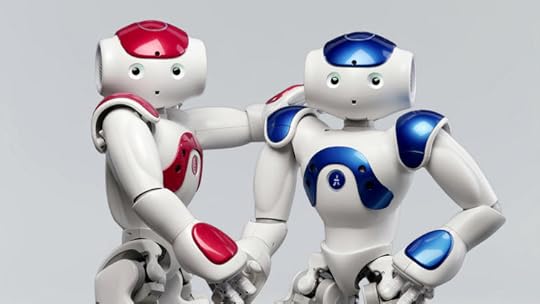

Nancy and Vincent: Friends or foes? Only time will tell. Photo: Picasa/Aldebaran

Soon to appear at the library in Westport, Connecticut: robots, two of them. “Vincent” and “Nancy” “have blinking eyes and an unnerving way of looking quizzically in the direction of whoever is speaking. They walk, dance, and can talk in nineteen different languages … [they] can recognize faces and detect where sound is coming from.” Ostensibly, the pair will help patrons find books and will serve as the centerpiece of a new robotics workshop. But whether these unfeeling golems are here to help or to serve as ruthless, lethal agents of the state remains to be seen. Anyone with late fees is advised to proceed with extreme caution.

Speaking of things you’re powerless to stop, however much you may wish to: Crime and Punishment, the Musical . (“I wouldn’t call it a rock-opera as such,” its director said.)

Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs “is not an easy read. It was written late in Victor Hugo’s career when he was living in exile on Guernsey, and his contemporaries dismissed it as an inferior work.” And yet it seems to have plenty going for it in the plot department: it’s “the story of a young man who is kidnapped, mutilated and sold to travelling entertainers, yet who retains his integrity and his dignity through the love of his adoptive ‘family,’ the eccentric philosopher Ursus, his pet wolf Homo, and the beautiful blind girl, Dea.” Sold.

Merritt Tierce, who was interviewed here last month, used to work at an upscale Dallas steak house, as does the protagonist in her debut novel. On two occasions, Tierce served Rush Limbaugh, who “left her $2,000 tips on modest-size checks, once with twenty $100 bills. ‘That was like blood money to me,’ says Tierce, who does not share Limbaugh’s social views.” So she gave it all to an abortion-rights group.

The trend of the “passport professor”: Why are so many Ph.D.s leaving America? (Why aren’t they? you might say.)

October 1, 2014

Typographic Sanity

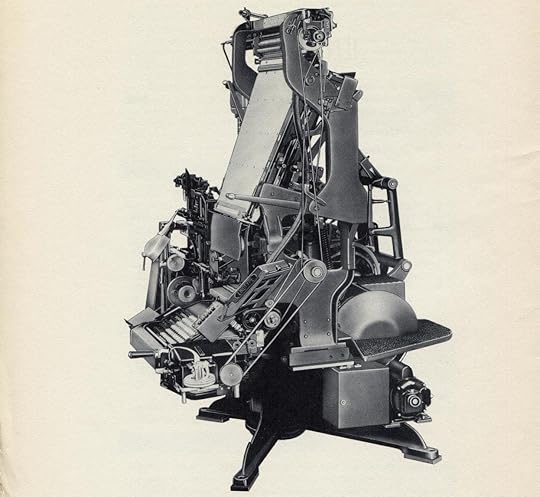

“The Blue Streak Comet,” a Linotype machine.

There’s a post over at Print Magazine about Frank Romano’s new book, History of the Linotype Company, which chronicles the rise and decline of the Linotype, a “glorious contraption” that was not so very long ago the industry standard for printing newspapers, magazines, catalogs, you name it. I’d be lying if I said I knew how it worked—to look at it is to imagine it taking your hand off—but fortunately there’s Wikipedia, which explains:

The linotype machine operator enters text on a ninety-character keyboard. The machine assembles matrices, which are molds for the letter forms, in a line. The assembled line is then cast as a single piece, called a slug, of type metal in a process known as “hot metal” typesetting. The matrices are then returned to the type magazine from which they came, to be reused later. This allows much faster typesetting and composition than original hand composition in which operators place down one pre-cast metal letter, punctuation mark or space at a time.

The machine was invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German immigrant who set up shop in Brooklyn. At the height of its powers, the machine was used in eighty-six countries and in 850 languages. And the public domain is teeming with miscellany from the Mergenthaler Company, which produced an endless succession of handbooks, manuals, brochures, and pamphlets, among them Linotype’s Shining Lines, a sort of trade magazine with impeccably designed cover art:

The best publication I found is probably The Legibility of Type, a design fetishist’s vade mecum published by Mergenthaler in 1935; it opens with “Type Was Made to Read,” a kind of Lord’s Prayer for printers and typographers, as dictated by a foreman with an irritating tendency to speak in rhymed couplets:

Type Was Made to Read

“Type,” said the Foreman, “was made to read,

And that is a maxim it’s well to heed,

For the printer frequently gets a start

With a craze for ‘beauty,’ a bug for ‘art,’

Which holds him fast in a fearful gripe

And keeps him trying mad stunts with type,

With seventeen fonts and seventy styles

And borders by thousands and rules by miles.

“Type,” said the Foreman, “was made to read,

But the printer, oftentimes, in his greed

For novel features and ‘class’ and ‘tone,’

Forgets this fact he has always known

And sends out work that is fine to see

And ‘smart’ and ‘natty’ as it can be,

A job with a swagger and high-bred look,

But hard to read as a Chinese book!

“Type,” said the Foreman, “was made to read,

And that should serve as the printer’s creed,

For work on the Linotype machine

Or hand-set jobs should be clear and clean,

Not ornamental, obscure, bizarre,

Composed of all of the fonts there are,

But simple, legible, quiet, plain,

A joy alike to the eye and brain!

“For art in printing is not the way

Of wild extravagance, weird display,

But rather the unobtrusive thrall

Of type that gives you no shock at all,

But draws your eyes to the page with zest

And holds your mind to the thought expressed;

We must keep ourselves to this simple creed,

Type was made—and is meant—to READ!”

The same pamphlet offers “Typographic Sanity,” a bombastic plea for order in the increasingly chaotic world of typesetting. It’s impressively solemn, for a piece of writing about fonts:

As the cold gray dawn breaks upon the morning after an orgy of tangled type design, a weary printing industry shakes its aching head and asks, “Whither are we bound?”

The descent was easy; from black to blacker, from fanciful to grotesque, from freaky to freakier, but when we have plumbed the depths, when the tastes of printer, of reader, are all thoroughly debauched, when we have achieved the ultimate in blackness, in illegibility, in riotous disorder—then to seek the return to the brighter regions of calm and ordered sanity; to reaccustom our ink-sated and jazz-jaded senses to a normal scale of values—this is labor, and this is the path that still lies ahead of the users of type.

The wave of reaction against the excesses of the last few years has been inevitable. Throughout the whole mad era, the Linotype organization has pleaded for moderation; for the guiding hand of good taste and good sense in the laudable quest for freshness of expression. In the face of insistent demands from many of its customers for surrender to the vagaries of the moment, it has striven to maintain its policy of typographic sincerity and to issue only typefaces of lasting worth. It would be a simple matter for the Company to design and cut matrices that would sell.

It took far more vision to refuse to issue worthless types merely for profit, and instead to present only those faces which are fundamentally sound in design and character and which will be a credit to the publisher who uses them.

The policy is not new with Linotype. It goes back to the very beginning of the Company’s typographic activity. This principle has been stated, restated and reiterated. It seems sound and sensible now, because it was sound and sensible when it was announced, and common sense doesn’t change with passing years.

“Ink-sated and jazz-jaded”—this is the work of a copywriter who clearly dabbles in poetry.

If you’re looking to kill a few more hours, I can also recommend a 1951 brochure advertising Corona, a Linotype-designed typeface “tested to provide top-level performance in newspapers and catalogs”:

For sport, you can try various lines from it at cocktail parties—see how far “Probably at no other period in newspaper history has there been a need for printing news at such materially stepped-up speeds as were required during the recent hectic war years” gets you.

Crossroads of the World

Times Square from above. Photo: Anthony Quintano, via Wikimedia Commons

In Times Square, surrounded by embattled Elmos and superheroes, several of us stopped at the crosswalk to wait for the light to change. The blue font on the overhead news ticker looked so cartoonish, so sort of jolly, that it took a moment for the words’ discordant meaning to sink in.

It read: THREE WOMEN BEHEADED BY ISIS IN SYRIA.

I stood and stared in horror; next to me was a very old man bent nearly double by kyphosis.

“Was it you?” came a voice. I looked down; there was a guy in a tweed flat cap. “Was it you?” he said again, to the old man. The old man looked up at him in uncomprehending irritation.

“Did you do it?” the guy in the cap persisted, indicating the circling words above us.

The light changed then and, without acknowledging him, the older man began his laborious navigation of the crosswalk. Over his head, Tweed Cap gave me a broad wink. I looked away as quickly as possible.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers