The Paris Review's Blog, page 653

October 17, 2014

The Subjective Flow of Time, and Other News

Detail from Camille Grávis, Captive balloon with clock face and bell, floating above the Eiffel Tower, Paris, France, ca. 1880.

Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which just won the Booker Prize, tells the harrowing, oft forgotten story of Australia’s role in building the Thai-Burma Railway: “Although there were nine thousand Australian P.O.W.s who worked on the railroad, a third of whom died while imprisoned, the episode never took hold of the national imagination. Flanagan himself has said that ‘it’s a strange story that isn’t readily absorbed into any nation’s dreams.’”

Flanagan’s name is also set to appear on a special British postmark congratulating him on the Booker. “We’re really pleased to share his success in winning this renowned literary award with a postmark that will be delivered to addresses nationwide.”

“One way researchers have tried to measure the subjective flow of time is by asking people of different ages to estimate when a certain amount of time has gone by. People in their early twenties tend to be quite accurate in judging when three minutes had elapsed, typically being off by no more than three seconds. Those in their sixties, by contrast, overshot the mark by forty seconds; in other words, what was actually three minutes and forty seconds seemed like only three minutes to them. Seniors are internally slow tickers, so for them actual clocks seem to tick too fast.” (That’s from Lapham’s Quarterly’s elegant new Web site, by the way—note it.)

Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum, which provides sanctuary to exiled writers from around the world, celebrates its tenth anniversary this weekend with an event featuring their five current residents, Huang Xiang, Horacio Castellanos Moya, Khet Mar, Israel Centeno, and Yaghoub Yadali.

Why did Sartre refuse the Nobel Prize in 1964? “Sartre’s rejection of the Nobel Prize was not personal. It was metaphysical. Every act I take as a writer, Sartre was saying, affects the existence of my readers. Accepting the Nobel Prize would have been, for Sartre, to compromise the freedom of his readers. Indeed, it would have compromised the freedom of all mankind.”

October 16, 2014

A Complete Guide to Flinging in Oscar Wilde

August Macke, Eine Frau auf einem Divan (Woman on a Divan) (detail), 1914, watercolor on paper, 11.5" × 9".

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if you could talk a little bit about your life as a gay man.

CARSON

It’s been a somewhat checkered career as a gay man. I was never totally successful. I think it started in high school, when in grade ten or eleven I developed a fascination with Oscar Wilde. Some of my friends shared this fascination so we used to dress like Oscar Wilde and memorize his aphorisms and construct conversations in the lunchroom, as if we were Oscar Wilde and his friends.

—Anne Carson, the Art of Poetry No. 88, 2004

I also had an early fascination with Oscar Wilde, though mine hasn’t, to my knowledge, led to an exciting double life. In high school, as I read through Wilde’s plays and then some of his prose, I came to recognize a pattern: his characters were always flinging themselves onto sofas. That was the only word Wilde ever used for it, fling, and he used it inordinately, constantly; the more I looked for it the more it turned up. No one in Wilde’s domain, it seemed, could get any thinking or moping done without first flinging oneself onto the nearest possible surface—cushioned, ideally, but not necessarily—and lighting a cigarette or bursting into tears. Over and over again, his lords and ladies had no recourse but to fling. They never pitched, cast, heaved, hurled, or tossed.

I didn’t object to this, as melodramatic as it was. In fact part of me aspired to such melodrama: I imagined that in adult life I would be confronted with one impasse after another for which the only cathartic response would be to fling myself onto a couch, weeping, smoking, or both. I was looking forward to it—if anything, I disappoint myself today with how rarely I’m compelled to do flinging of any kind. Little did I know that, as a teenager surging with hormones, I was at peak flinging age, with my best flinging days right there for the taking.

To this day, though, I associate the verb with Wilde; he left his mark on it, or it left its mark on him. Since today’s his birthday, I found his collected works online and made sure I hadn’t been deluding myself. Lo and behold, an amateurish concordance confirms that fling is everywhere. Herewith, then: your comprehensive guide to flinging in Wilde. Consult it in moments of emotional strife, perhaps just before or after your own bouts of flinging, and know that you are not alone.

From Lady Windermere’s Fan (stage directions):

LADY WINDERMERE throws off her cloak and flings it on the sofa.

From An Ideal Husband (stage directions):

Then she flings herself down beside a sofa and buries her face.

From A Woman of No Importance (stage directions):

Gets up and flings himself sobbing on a sofa.

Enter Hester in terror, and rushes over to Gerald and flings herself in his arms.

From De Profundis:

It was a blow so appalling that I did not know what to do, so I flung myself on my knees, and bowed my head, and wept, and said, “The body of a child is as the body of the Lord: I am not worthy of either.”

From The Canterville Ghost:

Just, however, as he reached the top of the great oak staircase, a door was flung open, two little white-robed figures appeared, and a large pillow whizzed past his head!

Once in the privacy of his own apartment, he flung himself down on a small pallet-bed, and hid his face under the clothes.

Wishing to make an effective entrance, he flung it wide open, when a heavy jug of water fell right down on him, wetting him to the skin, and just missing his left shoulder by a couple of inches.

From The Happy Prince and Other Tales:

And he flung himself down on the grass, and buried his face in his hands, and wept.

The little boy stretched out his two arms and flung them round the Giant’s neck, and kissed him.

From Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Tales:

After breakfast, he flung himself down on a divan, and lit a cigarette.

Even when Sybil flung herself weeping into his arms, he did not falter.

He flung the capsule into the fire, and sank on the sofa with a cry of despair.

When he got upstairs, he flung himself on a sofa, and his eyes filled with tears.

In a moment he had seized Mr. Podgers by the legs, and flung him into the Thames.

From A House of Pomegranates:

The lad—for he was only a lad, being but sixteen years of age—was not sorry at their departure, and had flung himself back with a deep sigh of relief on the soft cushions of his embroidered couch, lying there, wild-eyed and open-mouthed, like a brown woodland Faun, or some young animal of the forest newly snared by the hunters.

Then at another signal they all flung themselves again to the ground and lay there quite still, the dull strumming of the zithers being the only sound that broke the silence.

The Lizards also took an immense fancy to him, and when he grew tired of running about and flung himself down on the grass to rest, they played and romped all over him, and tried to amuse him in the best way they could.

The people flung themselves on the ground and hid their faces, but I would not do so.

And the young Fisherman gave him thanks, and kissed the ring that was on his hand, and flung himself down on the carpets of dyed goat’s-hair.

Weeping as one smitten with pain he flung himself down beside it, and he kissed the cold red of the mouth, and toyed with the wet amber of the hair. He flung himself down beside it on the sand, weeping as one trembling with joy, and in his brown arms he held it to his breast.

And he flung himself down on the grass and wept.

And finally, from The Picture of Dorian Gray, the flinging mother lode:

The hot tears welled into his eyes; he tore his hand away and, flinging himself on the divan, he buried his face in the cushions, as though he was praying.

"What is it all about?" cried Dorian in his petulant way, flinging himself down on the sofa.

He felt ready to leap upon him and fling him to the ground if he dared to lift the gorgeous hanging that concealed the secret of his life.

The trees seemed to sweep past him in spectral procession, and wild shadows to fling themselves across his path.

Then he loathed his own beauty, and flinging the mirror on the floor, crushed it into silver splinters beneath his heel.

As the door closed behind them, the painter flung himself down on a sofa, and a look of pain came into his face.

Then he lit a cigarette and flung himself down on the sofa

Sybil rushed to her, flung her arms round her neck, and kissed her.

Yet, when her arms were flung round his neck, and her fingers strayed through his hair, he softened and kissed her with real affection.

Then she flung herself on her knees and kissed my hands.

He flung himself down on the sofa and turned away his face.

She flung herself at his feet and lay there like a trampled flower.

Then he rose from the table, lit a cigarette, and flung himself down on a luxuriously cushioned couch that stood facing the screen.

A look of pain came across him, and he flung the rich pall over the picture.

He frowned, and tearing the paper in two, went across the room and flung the pieces away.

He went towards the little, pearl-coloured octagonal stand that had always looked to him like the work of some strange Egyptian bees that wrought in silver, and taking up the volume, flung himself into an arm-chair and began to turn over the leaves.

A sea-monster had been enamoured of the pearl that the diver brought to King Perozes, and had slain the thief, and mourned for seven moons over its loss. When the Huns lured the king into the great pit, he flung it away…

“You won’t? Then I must do it myself,” said the young man, and he tore the curtain from its rod and flung it on the ground.

Then he flung himself into the rickety chair that was standing by the table and buried his face in his hands.

Then, stooping down and taking up the gold-and-purple hanging, he flung it right over the picture.

And Lord Henry flung himself down on the divan and opened his cigarette-case.

Lord Henry flung himself into a large wicker arm-chair and watched him.

With a stifled sob the lad leaped from the couch, and, rushing over to Hallward, tore the knife out of his hand, and flung it to the end of the studio.

A Sensual Act

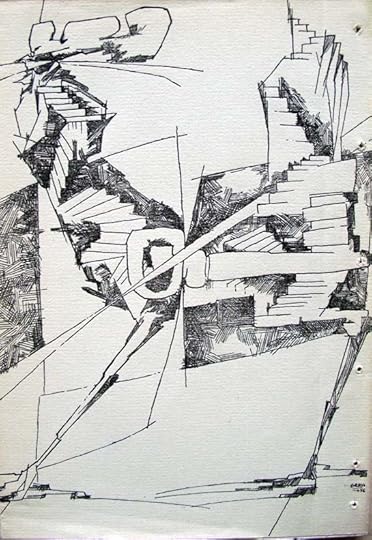

From Die Vorzüge der Windhühner (The Advantages of Windfowl), 1956.

I started writing and drawing at an early age … My first book was a book of poetry and drawings. Invariably the first drafts of my poems combine drawings and verse, sometimes taking off from an image, sometimes from words … With drawing, I am acutely aware of creating something on a sheet of paper. It is a sensual act, which you cannot say about the act of writing. In fact, I often turn to drawing to recover from the writing.

—Günter Grass, the Art of Fiction No. 124, 1991

Happy eighty-seventh to Günter Grass. That “first book” he refers to is Die Vorzüge der Windhühner (The Advantages of Windfowl), from 1956; Princeton’s Graphic Arts Collection has a few of the lithographs on their site. As Martin Esslin writes, “It is hard to tell whether the poems are there to illustrate the drawings, or the drawings to illustrate the poems”—which accords with Grass’s fairly circular description of his process. Here’s another:

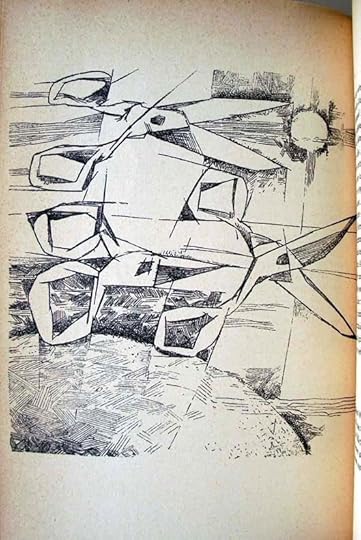

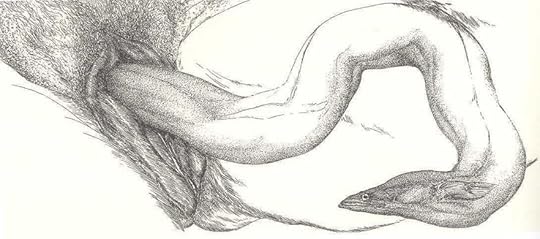

Not much of Grass’s prolific visual work is available online, but Millî Reasürans, a Turkish gallery, has a few images of the disquieting engravings Grass did for his 1977 novel, The Flounder, among them this unrepentantly phallic episode:

An engraving from Der Butt (The Flounder), 1977.

There are also a few drawings from Totes Holz (Death of Wood), which Grass discusses in his Art of Fiction interview:

I have seen and drawn dying, poisoned worlds. I published a book of drawings called Death of Wood about one such world, on the border between the Federal Republic of Germany and what was then still the German Democratic Republic. There, well in advance of the political union, a reunification of Germany occurred in the form of dying forests. This is also true of the mountain range on the border of West Germany and Czechoslovakia. It looks as if a slaughter had taken place. I drew what I saw there.

From Totes Holz (Death of Wood), 1990

John Russell wrote more broadly about Grass’s art in the New York Times in 1983:

His work relates to the ancient tradition in German art by which there is almost nothing of importance that cannot be made known to us with black ink on white paper. The marks in question may be made by cutting into blocks of wood, or with etching needle and copper plate, or with everyday pen and ink. Either way, black and white can tell us all that we need to know.

Final Chapter

A portrait of Kleist from Die Gartenlaube, 1858.

On November 21, 1811, the writer Heinrich von Kleist shot his beloved, the terminally ill Henriette Vogel, and then himself, on the banks of Kleiner Wannsee. The innkeeper who housed them the night before described the couple, thirty-four and thirty-one, as cheerful and voluble; Kleist wrote in a final letter to his sister that he viewed death with “inexpressible serenity.” Although controversial, troubled, and financially unsuccessful in his day, he went on to achieve a monumental posthumous reputation and is today regarded as one of the finest writers—playwright, philosopher, and novelist—in the German canon.

Vogel was herself an accomplished intellectual. Theirs is one of the most famous suicide pacts in history, but the details are hazy—some accounts say the suicide was her idea, others that she wasn’t even his first choice, a theory espoused by the recent film Amour Fou. The exact location of the bodies is unknown.

Because of the nature of their deaths, Kleist and Vogel were denied church burial and were instead interred where they fell, by the lake. An immediate tourist attraction for romantic rubberneckers, the gravesite fell into disrepair for most of the nineteenth century. It was freshened up when Kleist was claimed by late-century nationalists and was commemorated with a large, Nazi-style stone for the 1936 Olympic Games. (The Nazis claimed Kleist as theirs, too, but they had to redo the stone when they discovered they’d accidentally inscribed it with a quote by the Jewish poet Max Ring.)

In 2011, the site was given the grand bicentennial treatment: paths were laid through the nearby woodlands, the area was landscaped, and both Kleist and Vogel were given fresh markers; hers is new, his is the old stone turned 180 degrees and inscribed, once again with the Ring quote: “He lived, sang and suffered / in gloomy and difficult times / he sought death here / and found immortality.”

The site is easy to visit; it’s on what’s now the southernmost edge of Berlin, a short walk from the S-Bahn Station through the woods. And when the sun shines off the lake and filters through the yellowing branches, it’s heart-catchingly beautiful.

I don’t know any Kleist by heart—one wishes to be the sort of person with reams of quotations at her fingertips in such moments, and I, instead, had to look up what I wanted on my phone. I was thinking of Kleist’s well-known essay “On the Marionette Theatre,” collected in the fabulous On Dolls. These are its closing lines:

“Now, my excellent friend,” said my companion, “you are in possession of all you need to follow my argument. We see that in the organic world, as thought grows dimmer and weaker, grace emerges more brilliantly and decisively. But just as a section drawn through two lines suddenly reappears on the other side after passing through infinity, or as the image in a concave mirror turns up again right in front of us after dwindling into the distance, so grace itself returns when knowledge has as it were gone through an infinity. Grace appears most purely in that human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or in the god.”

“Does that mean,” I said in some bewilderment, “that we must eat again of the tree of knowledge in order to return to the state of innocence?”

“Of course,” he said, “but that’s the final chapter in the history of the world.”

Weighing In, Part 2

This is the second part of an excerpt from Kerry Howley’s new book, Thrown . Read Part 1 here.

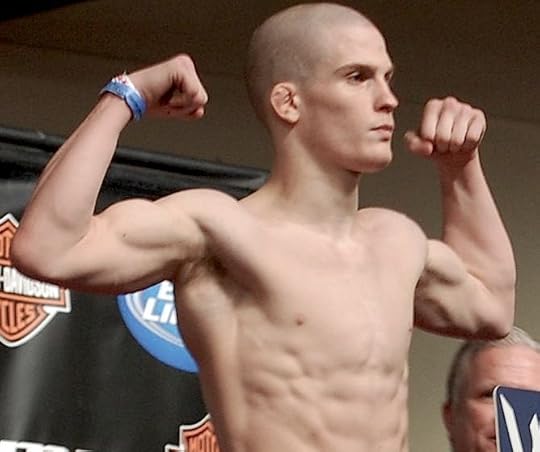

Erik Koch weighing in for a fight in 2010. Photo: flightlaunch, via Flickr

Erik spent the next morning resisting the intake of liquid. It was then that I recognized perhaps the only salutary psychological side effect of self-starvation, for Erik was about to weigh in beside his opponent, and he had not, as far as I could tell, thought about his opponent at all. He had seen Cisco by the blackjack tables a while back and briefly in line at the in-house movie theater, and the moment Cisco left his field of vision was the moment Erik’s thoughts returned to the Rio Buffet or gourmet granola or a single chocolate cupcake, though he was even beyond that now, because now he was dreaming of water. The thirst, Erik said, was worse even than the hunger. It made his teeth ache. Desiccated by forced dehydration, Erik’s skin had taken on a new solidity; pinched, it would pause before flattening back into itself. His ligaments had turned brittle. His elbow hurt. He sneaked, at some point, a sip of Crystal Light, but the powder at its base stuck to his teeth in his dry mouth and made his teeth hurt so intensely he regretted the transgression. He slathered himself in baby oil and stepped into the sauna and sweat, tensing hard as if he might will a few more drops of water from each straining muscle, until the sauna scale read 145.5. At his last fight, Erik had been so weak at this weight that a friend had to physically support him on the walk from the sauna to the scale.

In a packed hotel conference room later that afternoon, Erik watched Cisco play with the chains around his neck. There were reporters present from legitimate media organizations, which itself distinguished this entire endeavor from any fight I had yet experienced, and they came flanked by cameramen. The fighters were surrounded by teams of coaches in matching T-shirts; all were supported by sponsors more eminent than their local tattoo parlors. The fight would air on pay-per-view, and whoever won the main event would win fifty times what he might at one of the smaller, marginally legal fights I’d watched before.

Cisco and Erik both stared out past photographers crouching and clicking around the dais. When he heard his name called, Erik stepped onto the scale, which scrolled up to 146, the maximum allowed weight. His face went slack and his lips parted slightly. He flexed both arms. It was a less than convincing show of strength, a bizarre accumulation of protrusions popping under a translucent sheet of skin on his arms and abs. When he flexed, his two tattoos, “HD” for Hard Drive on the left and “Z” for Zombie Nation Army on the right, gleamed black and clean. He was nauseated and shivering with cold.

Erik stepped off the scale and posed for some shots with Cisco, who stood two inches shorter than Erik. Cisco was thin but not very, fully capable of fighting at 135 should he find within himself half of Erik’s willpower. They faced one another with fists raised, and Erik equalized their heights by forcing his head forward so his neck shot vertically from his shoulders. He had started doing this a few fights ago, he had informed me, and someone said that he looked “like an alien.” Now he was doing it every fight, and shaving his head to augment the effect.

“He looks like an alien,” I heard one of a dozen sportswriters tell the gentleman sitting next to him.

Erik stepped off the stage, and a girl in French braids handed him a large Tupperware container of twenty-four German-chocolate cupcakes.

Off-scale, backstage, I watched Erik slump against a wall and rip the top off a small plastic bottle of cherry Pedialyte: “Helps Kids Feel Better Fast.” He downed it quick as a shot and opened another and another. Twenty other fighters were drinking the same thing. Smiling teddy bears stared from between their thick fingers, then gathered on the floor in a growing mass of crushed plastic.

Erik ripped open a black duffel bag, inside which he had packed food and drinks that he knew from experience his shriveled stomach will not immediately return: cornbread, a single banana, V8, and a small turkey sandwich. He forced a large square hunk of cornbread into the round of his mouth and closed his eyes. Other fighters were staring. No one else had courier-delivered cupcakes or a canvas bag full of cornbread.

“Can I get some of that?” someone asked.

“Yeah, man,” Erik said, and tore off a generous piece. He shoved more moist cornbread in his mouth. His eyes went glassy as he splayed himself against the wall, a great goofy smile spreading across his face, and began to twirl a cupcake in his hand, peeling the foil wrap gently from the chocolate.

Erik said he felt dizzy, though one could tell from his weak smile that it was a pleasing, diaphanous drunk sugar-high kind of dizzy. It took him a moment to notice, when we skipped onto an elevator about to close, that the elevator was packed tight with Cisco and Cisco’s five-man Hispanic entourage. Erik came to consciousness in an awkward silence as we together ascended the fourth, the sixth, the eighth floor. He stared at the floor and rubbed his hand over the back of his neck. One of Cisco’s men leaned against the poster of Erik.

A small voice came from the back of the pack.

“Let’s jump him!”

Everyone laughed.

Erik had stocked the refrigerator in his room with small turkey sandwiches. He would incorporate food slowly, permitting himself only one every hour, along with a smattering of Ruffles, though chips are not an accepted part of the prefight diet. He popped onto the bed and watched, for the first time in weeks, something other than the Food Channel.

“Ruffles?” Wes asked. He had arrived just in time for weigh-ins.

“Yeah, Ken says it’s cool.”

Ken was Erik’s conditioning coach back in Cedar Rapids, and it seemed highly unlikely that he had made any actual judgment on the Ruffles.

Pettis swept into the room. Duke came in behind him. “What’s with the chips?” Duke asked.

“Anderson Silva eats two Big Macs before ev—”

“Calm down, you ain’t gotta justify it,” said Pettis.

Erik’s manager walked in, followed by a large ponytailed man carrying a leather bag.

“Doctor’s here!” said the manager.

“Hey,” said Erik, who was engrossed in another sandwich.

I thought perhaps the doctor had come for some sort of post-weigh-in physical, but instead of examining Erik he pulled out a fluid-filled bag attached to a tube and scanned the room, lips pursed, for a place to hang it. He settled on the large piece of hotel art hanging above Erik’s head, stood on his toes, and jolted it into position until the bag hung perilously from the corner of the frame.

“Can’t find your vein,” said the doctor as he stabbed Erik.

A minute later: “They’re so small.”

A minute later, to the manager: “Do we have any smaller needles?”

When the IV was finally in, the doctor gone, Erik watched Everybody Loves Raymond with rapt attention. His eyebrows kept rising, as if everything were slightly new to him. The colors. The fully internalized presence of other people. The way their voices travel through space. Erik’s exposed abdominal muscles were disappearing under a blanket of skin. His transformation was that of a wilted houseplant newly watered, stiffening back into life, and like a houseplant in revival it was a change only slightly too slow to see. For the first time in days, he was following the back-and-forth of rapid-fire conversation. This episode of Everybody Loves Raymond was funny. It was the funniest thing he had ever seen. When he laughed, the knobs reappeared in muscle, then receded back under the swell. He ripped off a piece of turkey club with his teeth.

“What happened with that girl?” Erik asked Wes during a commercial. Wes was playing with his phone on an armchair.

“Didn’t work out,” said Wes. “She was, you know, an older woman.”

“How old?” I asked.

“Like, almost twenty-six.”

Erik’s phone rang, and he ignored it.

“When are we going to the Rio?” Wes asked.

Erik didn’t look away from the screen. “I think that’s a bad idea.”

Erik’s right arm lay palm up on the bed, so as not to disturb the IV. In the window that ran the length of the room, evening was shading into night and lights were beginning to glow on the strip.

“I read on the Internet,” Erik said, “that people get food poisoning there.”

* * *

Erik fights Francisco Rivera.

Reporters wanted to talk to Erik. Not many, as Erik was relatively unknown, but some. One of these reporters was a fighter herself, and in her Erik took great platonic interest, as if they shared something intimate I myself could never know. Erik introduced me as we stood beside the octagon of the lush Tapout gym. “She’s a writer,” he added.

She had a list of questions on a sheet of paper, and after every one Erik said, “Good question,” though they were by no means particularly distinguished lines of inquiry, and in any case would only lead to a write-up on an MMA Web site with which I was not familiar. The entire errand seemed to me unnecessary.

She reached the end of her list, and turned to me. “Who do you write for?” she asked.

I felt Erik’s gaze upon me, as if I were being tested—as if, confronted by a “writer” whose intentions he understood, my presence in his life was suddenly inexplicable. There was a long, uncomfortable pause. I could hear a man grunting as he lifted weights in another room. Who did I write for? I had recently written a paper for Professor Richard Knowles, who had awarded that paper a D and threatened to fail me for the course.

“Well, it’s complicated,” I said, glancing at Erik, who looked somewhere between skeptical and annoyed by this answer. I panicked. “I write for the Cedar Rapids Gazette.”

Erik smiled in that bright-eyed, surprised way one smiles when one has solved a problem.

“So you’re going to write about this fight for them?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, greatly displeased by this development, “I do plan to.”

It was more than a little alarming that Erik would now expect a write-up in the sports section of his regional newspaper, but I put my hypothetical association with print journalism out of my mind as we dealt with a succession of actual reporters.

“I didn’t have a job. I didn’t have any way of making money,” Erik told someone on the radio. “I just decided to train six or seven hours a day,” he told someone from another MMA site. “Most people won’t do that.”

Erik did not particularly want to talk about his fluidity, his striking, his record; he wanted to talk about everything he had given up, all the possible lives he had rejected. He did not have a “back-out plan” he insisted over and over until I could see rowboats burning in his wake. Had he been able he would have told you from which particular sacrifice every piece of him emerged—the narrowest hinge of his hand, the curve of his neck, systole and diastole. How impressive Erik was before the microphone! Even when he could feel his stomach curdling and his eye sheen shriveling, his words were smooth and full. Often the question of from where Erik Koch had come—he was described to himself by interviewers as having “burst out of nowhere,” which was an invitation to an origin story—involved a kind of generational inevitability. He was the “new breed” because he was well-rounded, and he was well-rounded because he hadn’t trained as a wrestler or a kickboxer but as a mixed martial artist, and this was possible because he had come of age in a different world than that of his older opponents. Sometimes he had started training at ten, sometimes eleven, sometimes sixteen or seventeen, but always he was “just a kid” and always MMA was a thing he’d latched onto, hard and of his own accord. It had been there to pull from the air like oxygen and like oxygen his body just knew how to absorb it, break it down, become the thing he’d found. “My brother taught me” is not a story about sacrifice, which is perhaps why the brother remained an anonymous figure around which conversations danced.

In Cedar Rapids that evening, the members of Team Hard Drive make their way to a viewing party at an establishment that sponsors Erik, known to the fighters as Cici’s but formally and fittingly “Cici’s Pizza Buffet.” The fighters bring their kids, mittens hanging by strings from their sleeves, and let them loose to play arcade games in the back of the restaurant. The adults drink Coke out of tall plastic cups and ignore the fights before Erik’s fight, making fun of the one guy they always make fun of. The pictures flickering across the screen are familiar; they know the cast by name. There is the octagon, cerulean blue and crosshatched by red beams of light. There are the ring girls and the long camera shots that follow them around the ring; there is the kiss they blow to the camera as they twirl and sit back down. There are the referees the camera stops and acknowledges—Herb Dean, Big John McCarthy, Steve Mazzagatti—and the top-tier ticket holders it humors, platinum-haired women in diamonds and glittering tanks on the arms of hairless, polished, elaborately tattooed men. There is Stephan Bonnar’s boyishly jacked inflection carrying the viewers through each hit: Oh and a straight right drops him; Michael’s is all over him with some vicious ground and pound; He landed that left hook earlier; Smiled and answered with a laser straight right hand, right down the middle; Armbar, it’s on! There is Bruce Buffer’s voice, operatic in scope, hailing the arrival of each fighter into the sacred space with oceans-deep rich, rolling swells of sound that rise gently and dip hard with the demands of the ritual welcome.

Erik has his own warm-up room and Duke and Pettis are there, gently there, minimizing their presence as Erik hops and swings at imaginary opponents and as the fights tick by. Nothing is articulated here. There is a television in the warm-up room but no audio; hits happen soundlessly, chased by the low boom of the crowd outside. Duke slides cracked red mitts onto his hands and stands in front of Erik, who thrusts his shins into them. Thwap. Pettis sits on a metal bench and stares at the screen, worrying his knuckles, crack crack, sucking on the lace of his hoodie.

Erik’s is the ninth of eleven fights tonight, which means he is a “contender” but not yet a “champion,” and the pressure implied in this distinction is considerable. He is wearing white shorts that crink and whistle as he walks and although he looks hydrated and healthy, it is hard to imagine this slight white figure—“Powder” people will call him from the stands; “he should get a tattoo of a tan,” someone will tweet—conjuring the kind of power it takes to throw any man to the ground.

Everything is waiting. He waits for Pettis to put on some pads so he can punch them and he waits for the seventh fight to end and the eighth fight to end and he waits for the room-rocking thump-thump of his entrance music and waits for Duke and Pettis to gather behind him with his banner and waits for Pettis to slather Vaseline on his face and then he is in the cage, finally in the cage, only now he is hopping around and waiting for Cisco the Californian, who evidently has many more fans in Vegas than does Erik, and he waits for the cry of Cisco’s crowd to move up through his feet to the tips of his fingernails and something is gathering and then finally Steve Mazzagatti, a man Erik has watched from a couch in Iowa referee fights for years and years, says, “Let’s get it on,” and Erik begins to sway.

He and Cisco step forward and backward, forward and backward, rocking in hypnotic rhythm, a low kick here, a missed uppercut there, and Erik leans low and right and swings his left shin high into Cisco’s head and the head whips out of rhythm and Cisco drops like a dead man and Erik lunges onto Cisco and Steve Mazzagatti jumps in between them because Erik Koch is the winner and the champion and millions of people are watching and the whole room is standing and grown men are moaning and as I look at my hands wet with my tears, Erik flexes every muscle in his body—hands fisted, arms low—and screams.

This is the second part of an excerpt from Kerry Howley’s new book, Thrown . Read Part 1 here.

© 2014 Kerry Howley. Reprinted with permission of Sarabande Book.

Kerry Howley’s work has appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, The Wall Street Journal, Slate, and Bookforum. She holds an M.F.A. from the University of Iowa, where she was an Arts Fellow and the Provost’s Visiting Writer in Nonfiction.

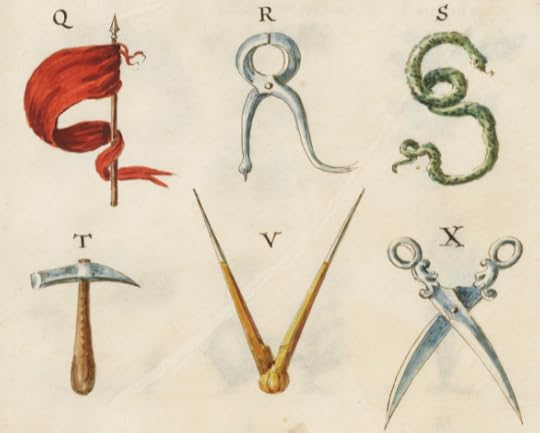

An Alphabet of Things, and Other News

Detail from Giambattista Moretti’s Alphabeta, 1737.

Should the National Book Award rethink its longlist? “It’s hard to stir interest in the same subject twice, which is what the National Book Award is trying to do.”

Down with adverbs! “Only two classes of people, it seems, stick up for the adverb: young adults and members of the bar.”

At auction next month: Giambattista Morandi’s 1737 Alphabeta . (A bargain at two- to three-thousand euros.)

In the forties, America believed it had at last conquered all airborne illnesses. The secret: germicidal lamps, which at the time were a source of extraordinary optimism. “We can look forward confidently to the fact that within another few years at most, control of airborne infection will be on its way to join control of infections through water, milk and solid foods. Another great frontier will have surrendered to man’s onward march.”

The Italian novelist Domenico Starnone is fed up with people who think he’s the elusive Elena Ferrante: “Ferrante is not the only one to have written about abandoned women, you know … Let’s say I am Ferrante, or that my wife is. Explain to me one thing: given that it is so rare, in this mud puddle that is Italy, to have international reach, why would we not make the most of it? What would induce us to remain in the shadow?”

Beethoven gets real: “Everything I do apart from music is badly done and stupid,” he once wrote.

October 15, 2014

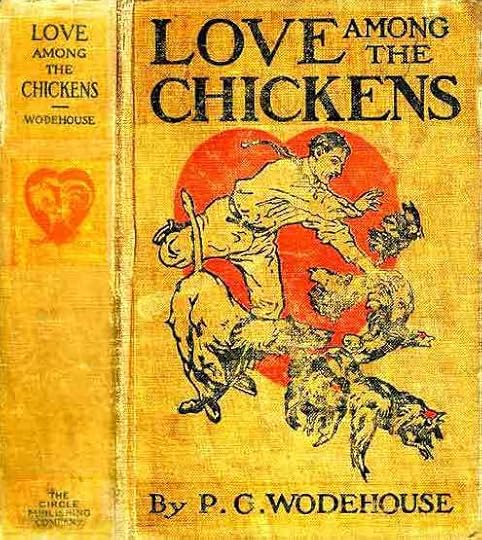

Love Among the Chickens

INTERVIEWER

Of all the books you’ve written, do you have any favorites?

WODEHOUSE

Oh, I’m very fond of a book called Quick Service and another called Sam in the Suburbs, a very old one. But I really like them all. There are very few exceptions.

—P. G. Wodehouse, the Art of Fiction No. 60, 1975

I wonder how Wodehouse (born today in 1881) came down on Love Among the Chickens, one of his earlier novels and, to my mind, one of his strangest. It is, as its title page quite clearly states, “A Story of the Haps and Mishaps on an English Chicken Farm.” (Wonderful use of haps, there. Why is it that we only hear of mishaps these days?)

Wodehouse published Chickens in 1906, but he wasn’t very pleased with it, apparently, because he rewrote large portions of it for a new edition in 1921; his new dedication is frank about the earlier version’s shortcomings. “There was some pretty bad work in it, and it had ‘dated,’” he writes.

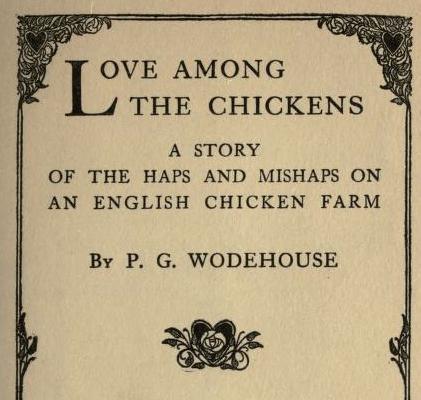

The book was illustrated by Armand Both, who spared no expense in his depiction of cruelty to animals:

The novel is in the public domain, so you can read it at your leisure, when you’re feeling down, when life’s trials have you seeking the solace of poultry, when nothing other than a farm romance will suffice, et cetera. To pique your interest, allow me to quote a bit toward the beginning in which Wodehouse establishes his premise with admirable concision:

“Listen to me! When I said that we were going to keep fowls, I didn’t mean in a small, piffling sort of way—two cocks and a couple of hens and a golf-ball for a nest-egg. We are going to do it on a large scale. We are going to run a chicken farm!”

“A chicken farm,” echoed Mrs. Ukridge with an affectionate and admiring glance at her husband.

“Ah,” I said, feeling my responsibilities as chorus. “A chicken farm.”

And so they do.

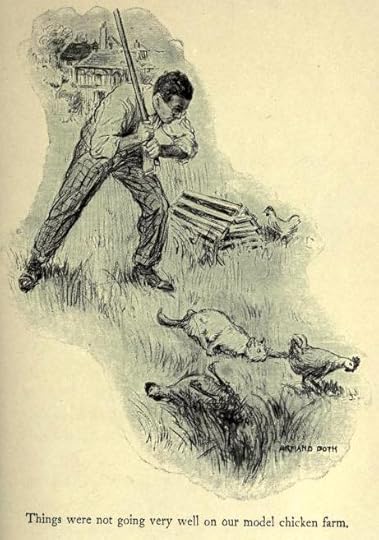

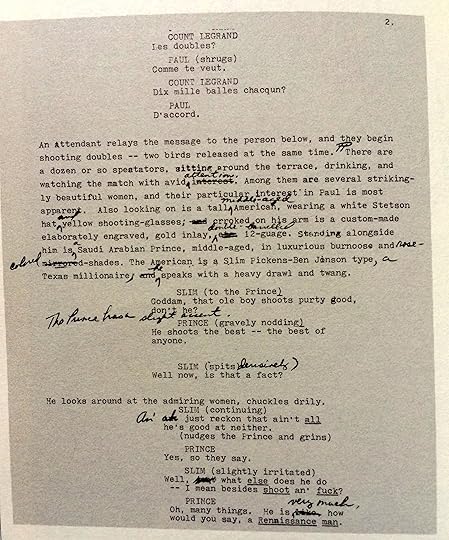

That Ole Boy Shoots Purty Good

You may well have seen that our new Fall issue features a loping and very funny editorial exchange between George Plimpton and Terry Southern, one that captures both men at the height of their wit—and especially Southern’s, shall we say, distinctive style on the page. (“Yes, it’s true I’ve a rather crackerjack interview with good Hank Yonge tucked away in the old jock-strap, and naturally I’m eager to see it get the sort of dignified dissemination its merit does warrant,” a not-atypical sentence goes.)

The Review has published a lot of Southern over the years. Issue 138, from Spring 1996, has a particularly rich cache of what the man himself might call “Quality Lit,” not just by Southern but about him. It is, essentially, a Terry Southern memorial: when Southern died in October 1995, Plimpton and the staff collected some of his unpublished work and a series of remembrances in his honor. Among the tribute are four pages from an unfinished screenplay, which we’ve reproduced below. It’s just enough to make you wish he’d seen the thing through, and just enough to make you wonder what the hell the movie would’ve actually been about. Skeet shooting? Drug-addled romantics? The French?

As a salute to Southern, who died nineteen years ago this month, for the rest of October we’re offering copies of Issue 138 for only fifteen dollars—fifty percent off the regular price. The issue features an essay by Southern, an interview with him, and remembrances by William Styron, George Plimpton, and Henry Allen. There’s also of course a glut of material having nothing to do with Southern whatsoever, if that’s more your thing: fiction by Junot Diaz and Milan Kundera, interviews with Richard Price and Billy Wilder, poetry galore, et cetera, et cetera. Get a move on!

Weighing In, Part 1

Watching a cage fighter starve himself.

Photo: Jeremy Brooks

“Four eggs,” I instructed the waiter at the finest restaurant in the Palms Casino Resort.

“Egg salad?” He was in a starched suit, pouring water into a delicately lipped glass.

“No, four hard-boiled eggs.”

“Four eggs.”

The waiter returned with four eggs huddled in the slight depression of a sizable dinner plate, as if to further diminish the sad feast through a trick of scale. Each egg had been deshelled, which was, I supposed, the benefit of ordering hard-boiled eggs at the finest restaurant in the Palms. Erik was a few flights up in his hotel room, showering after a workout, but he had asked that his meal be ready when he descended, and I feared displeasing him.

Though his mentor Duke, his roommate Pettis, and his manager could be found dispersed among the card tables and slot machines, not a single member of Hard Drive, Erik’s fighting collective in Cedar Rapids, had ventured with us to Las Vegas. Following a momentous schism between him and his brother, Erik had been “banned for life” from the gym and its environs.

Banished, Erik had returned to Milwaukee, to his warm, fast-talking Italian American coach, to his potential as one of the youngest men in the most prestigious promotion open to men who weighed in at 155 pounds. From their offices in Vegas, connected people continued to call him in Milwaukee, and it was as if he had never made the mistake of going home. Would he like to be in the official UFC video game? They would fly him out to LA, take measurements, and then boys everywhere would fight their friends in the avatar form of Erik “New Breed” Koch. Pettis was asked to be a judge for the Miss Wisconsin USA pageant and, in declining the offer, sent Erik in his stead. Erik met, at the event, the manager of a Jersey Shore cast member. Would Erik like to be on an episode of DJ Pauly D’s upcoming reality spin-off show? He said he very much would like that. He was unattached, alone, free to make commitments to as-yet-theoretical reality shows as he pleased.

Erik at last arrived at the restaurant, sat across from me without a word, unrolled from the napkin his knife and fork, and began the surgical egg procedure with which I was, by then, familiar. I would have liked to discuss our surroundings, as it was my first encounter with a professionally run promotion and I had many astute observations on the subject, but he ate with an air of sacral solemnity I did not wish to desecrate by speaking. It was my twenty-ninth birthday and I had not told a soul in the world.

You may think that a starving man on rations, faced with the few calories he is allowed, would proceed with survivalist immediacy to incorporate whatever was laid before him. But the rationed man is all precision; he sees, in his allowance, fine nutritious distinctions you do not; and so when Erik finally raised his knife to halve his egg, he did so with great deliberation. With his knife he hollowed the half yolk from its white skin and deposited the caloric yellow mass onto his plate, where it sat uneaten like a pat of butter. He scraped offending yellow flecks from the egg’s gelatinous walls. He slid the flat of the knife against the plate, shedding shavings of yolk onto the porcelain, put his knife down, and placed the white in his mouth. He approached the second half of the first egg. This would be Erik’s last watery wisp of permitted food before weigh-ins; he would not eat again for thirty-five hours. Erik’s frame had already cratered into a landscape of shadows and white skin stretched tight over bone.

It would not have occurred to most 180-pound fighters that they might, through force of will, gain admission to the 145-pound weight class. Certainly the Californian Cisco Rivera, a full two inches shorter than Erik, would not be losing a fifth of his body weight. Erik had, back in Cedar Rapids, informed me that he could lose thirty-five pounds, weigh in, binge like a feral Labrador, and feel ready to fight a day later simply because he was twenty-two years old. Self-starvation was the biggest challenge of his chosen vocation, every prefight diet was more painful than the last, and two years hence, Erik said, the drop would be impossible. His ability to boomerang from 180 to 145 and back up to 160 would diminish unalterably with age; he would be impelled to fight among a slightly more substantial group of men, the “lightweights,” which included his roommate Pettis, and so was something neither of them deigned discuss. Thus it was that one of the youngest fighters in the promotion saw only days slipping away. Two years he had in which to get a title shot and win the opportunity to fight the invincible Brazilian José Aldo, who would probably still be champion at 145. This was, of course, absurd, given that Erik was nowhere near title contention. But thoughts of the title pushed Erik through the long days of his weary yolk-scraping existence.

After the eggs, Erik opened his eyes a little wider, and we took the casino elevator up to his room.

“This is what you got?” I asked.

“This is Whole Foods peanut butter, they make it in a machine there,” Erik said. I had been talking about the branded T-shirts and laptop bags and hats, but did not interrupt him as his focus shifted back to food. He pulled a plastic tub out of the shelf under his bedside table, where it lay next to bananas and a loaf of bread.

“This is chocolate peanut butter from the machine. This granola,” he said, holding a plastic bag of cereal, “is sick.” He replaced the granola and seized on a bag of chips. “Cheddar and Sour Cream Ruffles. These are the shit.”

I eagerly assented to their excellence, as if I were quite familiar with them. I very much wanted Erik to feel buoyed by the fact of my company. Erik had had a succession of best friends he’d cut off suddenly and without explanation, inventing supposed slights he would never forgive. It was part of a pattern integral to his personality, and quite likely attributable to his sociopathy as diagnosed by the Internet.

Erik Koch

The thought that Erik might at any moment terminate our relationship so thoroughly haunted me during our trip that even now I associate casinos with insecurity. Should he decide to stop answering my calls and requesting my presence, I would have wasted five months on a man of no use to my project, a project of importance not only to me but to future students of descriptive phenomenology. And I simply could not abide the idea that some other space taker—someone larger, and more given to Midwestern colloquialisms—would take the space I had so carefully reserved for myself by Erik’s side. That someone else would be sent to order his eggs, someone else privileged with the knowledge that the old Vedepo-induced injury in his elbow hurt more intensely as he grew more slim; this was enough to make my stomach turn, which was in itself a silver lining, because it allowed me to share, on that trip, something of Erik’s distance from the possibility of food.

I had arrived in Las Vegas the day before, anxious to see the American city considered most fighterly, but underfed Erik did not want to see the Cirque du Soleil or the Hoover Dam; he wanted to go to Walmart, and so to Walmart we went. Outside, on the mountain-edged expanse of pavement cooking in desert sun, Erik was all angles and shadows, bounceless, frail, a dusting of hair over his shaven head. Walmart fluorescence added a yellow cast to his white skin, turned olive those undereye pockets of gloom. Raccoon-eyed and ravenous, Erik slothed through each aisle, his gallon jug of the day’s permitted water consumption hanging low at his side, dragging him down, slowing his advance. He needed baby oil, he’d said before we left. But then I followed him into the hardware aisle, walled in by dozens of varieties of sandpaper, and we did not appear to be progressing toward the aisle marked “baby” at the far end of the store. He hitched up his jeans with his free hand as he walked; they slipped again down his sharp hips. He was walking away from the baby section and toward the chip aisle, where he stood for a moment staring at the Cheddar and Sour Cream Ruffles. While he described the slow throb of his esophagus I imagined the whole pipeline glowing as in some educational film about the digestive tract. He picked up the Ruffles and made it halfway to the register before remembering the oil for which he had come.

“What,” Erik asked the taxi driver on the way back to the Palms, “is the best buffet in Las Vegas?”

Back in Milwaukee, Erik told me, the Hyundai Elantra he’d been borrowing was papered with oil-stained wrappers: Burrito Supreme, 100% Beef, BK Stacker, remnants of forbidden foods vicariously enjoyed.

“I’m buying you a burrito,” he’d say to Pettis. “Eat it. I want to smell it.”

Friends ate the fast food Erik purchased slowly, wafting ground-beef steam toward their skeletal driver, leaving the paper crumpled and the scent hovering. This seemed to me deranged culinary masochism, but Erik insisted that he could not possibly starve himself so effectively were he to take his mind for a moment off of food. And in this, Vegas was cooperative, for to the starving man Vegas offers comforts one does not necessarily associate with the city. At the Rio Resort and Casino, for instance, if you can see past the seamlessly linked rooms for poker and keno and slots, past a singing girl in sequins, a stream of light, a wisp of smoke, if you can see past plastic neon-lit flames leaping over paisley carpet and the “future Chippendale fan” pink onesie featured in the gift-shop window, past the spiraling staircase up to the heavily curtained Italian restaurant meant to evoke fine dining but suffering in that regard from its direct adjacency to Wetzel’s Pretzels, if you can gaze beyond the gargantuan goggle-eyed head hanging from the Masquerade Room, or if you are, like Erik, quite literally starving, you will notice that this city is not merely a purveyor of monetary risk but a purveyor of food. You will notice that this food is marketed chiefly through the promise of quantity, specifically through the provision of casino buffets. It is these buffets that interest Erik, their promise, their hideous abundance. For $39.99 one can in fact purchase an all-day pass to many buffets, a package known as a “buffet of buffets,” inclusive of seven—as in wonders of the world or deadly sins, but pertinent to only one sin, that of gluttony—in-themselves-perfectly-adequate self-serve experiences: Le Village Buffet, the Emperor’s Buffet, Spice Market Buffet, Flamingo’s Paradise Garden Buffet, Lago Buffet, Harrah’s Buffet, and the “world’s most acclaimed buffet,” the Carnival World Buffet at the Rio.

“The best buffet in Las Vegas,” said the Taxi Driver, “is the Rio Buffet.”

Erik smiled and leaned back into the pleather. He had never been to the Rio Buffet but nevertheless qualified as a Rio Buffet expert, having taken the virtual tour but more importantly having spent many hours visualizing his sublime deliverance from self-deprivation. In the twenty-four hours between weigh-ins and the fight, Erik would gain twenty pounds, and he took great pleasure in imagining of what those pounds would consist. The Rio Buffet, he informed me, offered three hundred distinct dishes, seventy varieties of pie, an array of “bars,” including a sushi bar, a taco bar, and a stir-fry bar. He knew its small army of friendly spoon-holding servers, its fifty yards of curving black countertop, its unaccountable progression from sausage pizza to cocktail shrimp to scrambled eggs to lentil soup to crab legs to fried fish to sushi to green salad to gravy-slathered pork chops to honeyed ham to flank steak to barbecue ribs to burritos to tacos to waffles to spring rolls to dumplings to sweet-and-sour pork to eggs Benedict to bacon to one giant vat of ketchup to croissants to cubed mango to green-bean salad to seven kinds of lettuce to the gelato-and-pastries bar whose delights are too many to enumerate but which Erik would attempt to enumerate if given the chance.

The Rio was only one part of the plan, which also included spaghetti and meat sauce and an entire loaf of garlic bread from Battista’s, subs from the local Jimmy John’s and twenty-four German chocolate cupcakes being mailed overnight from Milwaukee by a pair of baking groupie sisters who had arranged for a courier to hand cupcakes to Erik the moment he stepped off the scale.

“I am a fighter,” Erik told the taxi driver. “I am planning what to eat before the fight.”

“You shouldn’t overeat,” said the driver.

“Anderson Silva eats two Big Macs before every fight,” said Erik. “It doesn’t matter that much.”

The conversation paused as traffic crawled past the MGM Grand, hulking and soot-stained in the midmorning light.

“Have you tried the NASCAR six-pound burrito?” Erik asked. The NASCAR Café’s six-pound, two-foot burrito was also part of the plan.

Photo: Neon Paradise

In the hotel room that night, watching the Food Channel and fiddling with his phone, Erik shivered, skeletal, in his hoodie. “Let’s go to Rio,” he said, heavy-lidded, grim. “I mean just to see it.”

It was ten P.M. I would have voiced a preference to take in a late film at the casino’s movie theater, but I did not want to risk being on the wrong side of Erik’s Manichean inclinations.

Erik and I left the room, descended in an elevator with Erik’s picture hanging in it—TICKETS ON SALE WEDNESDAY—passed a young crowd at the blackjack tables and a not-at-all young crowd at the slot machines, exited into the pedestrianless abyss that was the space between off-strip Vegas casinos, and walked to the Rio. Beyond the Mahjong and Keno tables, the poker-tournament competitors in cowboy hats, Erik pointed to a sign: THE CARNIVAL WORLD BUFFET. We passed through swinging doors into a vast shellacked cafeteria.

“It’s closed,” I said.

The food had been vacated. What was left was all fluorescent light, clean steel, and frosted glass. The only person in the room was a man behind the counter, wearing what looked to be a gas mask and pouring steam out of a tube. Erik attempted to penetrate the mask by shouting.

“I am a fighter,” he said, pointing to himself. “I want to come here tomorrow.”

The man in the mask nodded a quick, deferential, non-English-speaking nod.

Affixed to all fifty-feet of the gleaming counter were black plaques etched in white. Erik began at the north end of the room.

“Pizza,” he read off the plaque, and paused, staring at the aluminum heater and readjusting his grip on his jug of water. A light on the far end of the room flickered.

“Shrimp scampi.”

I walked into the expanse of rag-wiped tables and sat down to endure Erik’s fantasy with what I think to be commendable patience.

“Poached eggs,” said Erik. His face had regained its yellow pallor and seemed to recede into his hoodie. “Scrambled eggs.”

Twenty minutes later Erik reached the gelato. The steam cleaner had left.

“Let’s go,” said Erik, and we padded back through the casino, where, at eleven P.M. on a Tuesday night, only the committed or addicted remained.

This is the first of a two-part excerpt from Kerry Howley’s new book, Thrown . Part two will run tomorrow.

© 2014 Kerry Howley. Reprinted with permission of Sarabande Books.

Kerry Howley’s work has appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, The Wall Street Journal, Slate, and Bookforum. She holds an M.F.A. from the University of Iowa, where she was an Arts Fellow and the Provost’s Visiting Writer in Nonfiction.

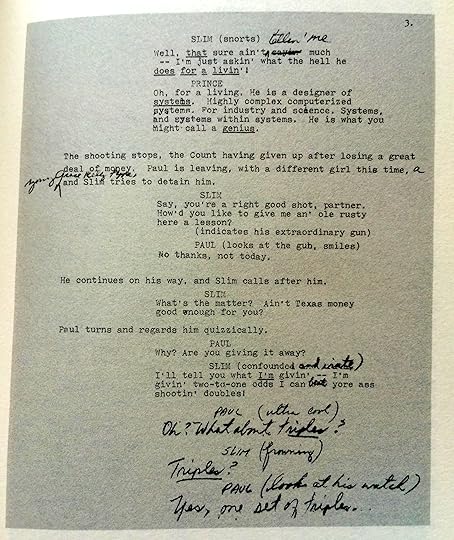

Epicurean Materialism

Photo: Clemcal, via Flickr

Be not astonished at new ideas; for it is well known to you that a thing does not therefore cease to be true because it is not accepted by many.

―Baruch Spinoza

A little after nine, on the western outskirts of Berlin, we tried to find a bite. The first restaurant was filled with merry revelers and contained a video of a brightly burning log, but we were informed that a party was in progress, which went some way toward explaining the five dirndls, two pairs of lederhosen, and single loden jacket on the premises. That left us with a single option: the train-station restaurant.

The train-station restaurant appeared to be closed but was in fact merely deserted. A visibly drunk waiter gave us our choice of any table in the two massive dining rooms. Both were funereal, brightly lit by a series of 1980s chandeliers and enlivened by sepulchral muzak. The menu was strange and dubiously cross-cultural; we ordered dumplings. The drunk waiter conferred with a man in chef’s whites in the corner while they stared at us.

Some minutes later, the chef himself approached our table. They were out of everything but turkey dumplings, he said. Would we like turkey dumplings? The answer was obviously no, but we smiled and said, Of course, and sure enough, the turkey dumplings appeared. Aware of potential scrutiny, we feigned great enthusiasm. The drunk waiter, who had started hiccuping cartoonishly, wove by a couple of times. To our immense relief, a small group of Japanese tourists wandered in and sat on the other side of the dining room.

It was at about this time that the chef reappeared at our table. He was carrying a plastic bag and smiling mysteriously. From the bag, he removed a book. He put it down on the table with an air of revelation. We looked at it. It was a German copy of Spinoza’s Ethics.

“Spinoza!” he said.

“Ja!” we agreed.

Had we read it? He asked. Not for a while, we said apologetically. (I wasn’t even sure the survey-course translation I’d read ought to count.) But we’d heard of it? Ja, ja! We said. Natürlich! I should add here that the chef did not really speak English. Which is to say, his English was about a thousand percent better than the average American’s German, and two thousand percent better than ours, but between us, there was very little possibility of having an in-depth philosophical dialogue. If, indeed, this is what was expected.

Yet, over the course of the next few minutes, he managed to communicate that he loved Spinoza very much. When he was sixty, he said, he planned to travel to Leiden and study Spinoza properly. He was now fifty-eight. I was jet-lagged, but tears still pricked at my eyes.

My friend recommended a book to him; he copied down the title with the air of one who takes recommendations seriously. Then he wrote down his contact information for us: name, e-mail address, phone number. He had a clear and handsome hand. Would we let him know, he said, if we heard anything about Spinoza? We assured him we would. We parted on warm terms.

“When you think about it,” said my friend, “turkey dumplings are a very Spinozan dish.” It was true.

We had thought to stay on a little, but then the waiter came around, turned out the lights, and slurred that he wanted to close and that we’d all have to leave. I am not sure whether the other party got to finish their meal. When we did exit, it was to find our friend the chef sitting outside smoking a cigarette. He hailed us. “Spinoza!” he said. We nodded happily. And then things went strange. “I go to Leiden when I am sixty,” he said. “I am going to be King of Europe! I am Catholic!” And, “Like Nostradamus, the prophecy, you know? Catholic! King of Europe!”

“Oh,” said my friend dejectedly, when we were out of earshot. “I guess he’s crazy.”

We heard his voice then, from behind us: “See you later, alligator! In a while, crocodile!”

Like a griffin will come the King of Europe, Accompanied by those of “Aquilon”: He will lead a great troop of red ones and white ones, And they will go against the King of Babylon.

—Nostradamus, Prophecy Eighty-Six

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers