The Paris Review's Blog, page 659

September 26, 2014

Staff Picks: Beckett, Boxtrolls, Bard

A still from Boxtrolls.

Reading a collection of letters from the beginning straight through to the end is one step up from reading the phone book. I know there are valuable bits throughout literary letters, but they’re so often scattered among details like how much so-and-so paid for a ham sandwich and how hard it is to find a good Danish translator. So I have not read all of the third volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters, but I have nevertheless spent a good deal of time with it. The years 1957 through 1965 find Beckett at the height of his fame. He writes very soberly but with affection and appreciation, no matter the subject. In response to Robert Pinget’s highly unfavorable reaction to Comment c’est, Beckett writes, “I am grateful to you for being so frank. That is friendship.” My favorite parts in the letters are the seemingly rare moments in which Beckett seems to loosen up, as when he writes to the radio producer and translator Barbara Bray, with whom he was close, “Bought six pairs of socks today in the Wednesday market. Very colourful. Not the socks. 5 francs a pair.” Or, in another letter to Bray, “Still drunk this morning after sudden hopeless useless midnight bucket of brandy and sitting in special ever since 37 pub and have yours to hand and in head grinding old poem in vain by Hölderlin influences entitles Dieppe circa 37 also…” —Nicole Rudick

I was appalled to learn from The New Yorker today of a London pop-up restaurant called “Death Row Dinners,” which will, for fifty quid, “incarcerate” you at “one of London’s toughest high-security restaurants, where our prison chefs serve up a five-course feast of their culinary twists on some of death row’s most interesting and popular last dinners.” It’s not that I find the concept tasteless—it’s that I thought of it first, two years ago, in a satirical essay about food and death. I was all set to litigate, but then I kept reading that New Yorker piece: turns out “Death Row Dinners” was deemed so offensive that the organizers shut it down, apparently after they were subjected to “seriously threatening behavior.” Still, I don’t want to miss out on any future business opportunities, so I’ll just go ahead and toot my own horn here: I had two other great restaurant ideas in my essay. One was Admiral O’Heimlich’s, a surf ’n’ turf pub where community actors feign asphyxia and the waitstaff teaches you how to save choking victims. The other was Turks and Cake-os, a turkey and cake shoppe kept at tropical temperatures and lit exclusively by sunlamps. I’m willing to speak to investors about either, or both. —Dan Piepenbring

Do the imaginative side of yourself a favor and go see Laika’s latest handmade creation, The Boxtrolls, which opens tonight nationwide. The film, based on Alan Snow’s Here Be Monsters!, is at times dark, at times heartwarming, and visually stunning all throughout—especially when you consider that a vast majority of the film, like its predecessors Coraline and ParaNorman, is painstakingly animated. (Full disclosure: my sister, Emelia, is one of the artists who designs and builds the puppets.) —Stephen A. Hiltner

As a Bard alumna, it would be unforgivably rude of me not to mention Alice Gregory’s magnificent profile on Leon Botstein, the president of the college, in this week’s New Yorker. In “Pictures from an Institution,” Gregory, a former Bardian herself, asks a question not unfamiliar to those who regard Leon as a beau idéal of intellectualism and progressive action: What is Bard without Botstein? He has, after all, “built [it] in his own polymath image,” and since he’s sixty-seven—having started as president in 1975, at age twenty-seven—the question of institutional identity is more pressing than ever. But Gregory doesn’t, can’t possibly, answer this. Instead, she shows us Botstein’s idiosyncratic mind. He is an educator; a father; an admirer of horology; a conductor; a raconteur; a man who used to be a boy who stuttered and was called Durachyok, or little fool; and the face not only of Bard but Bard’s Prison Initiative, a program that admits and awards college degrees to inmates. Gregory’s profile renders Botstein so well that we worry about Bard all the more acutely after reading it. —Caitlin Youngquist

Last week, I heard an engaging production of Beckett’s 1959 radio play Embers at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The experience compelled me to revisit What Where (1983), the last of Beckett’s dramatic works, which he wrote first in French, and then translated himself into German and English. Typically read, in part, as a sharp critique of totalitarianism, the short play features four “characters”—Bam, Bem, Bim, and Bom—“as alike as possible,” who engage in a series of interrogations, led by Bam, that allude to torture off-stage but which ultimately produce no knowledge or truth of any kind. What Where is well situated among Beckett’s other late minimalist pieces, such as Quad, Nacht und Träume, and Breath, and within his oeuvre at large: like so much of Beckett, it chips away at language until only its smallest pieces remain. At the end of its fruitless interrogations, Bam’s disembodied voice says all that it, or any of us, can: “Time Passes. That is all. Make sense who may.” —Charles Shafaieh

Vine—yes, the app—is known mainly for its emerging pseudo-celebrities and teenage Beiber wannabes, but I personally love it for the bizarre nonsense its six-second format allows. Some of the best Vine videos look like a cross between a Tim & Eric sketch and those compelling (if senseless) installation videos you see at certain galleries and museums. Birthday Salad’s collection of six-second loops is mesmerizing, a mix of old and obscurely sourced videos scored by leftovers from the Boohbah sound track. A bunny grooving in the moon? Tennis-playing airplane stewardess? Whatever this is? The genius behind the Birthday Salad account is no longer posting videos, by the look of it, but there are plenty of other moody masterpieces out there—enough to keep you entertained for days. —Justin Alvarez

Inside Albertine

Nations of the world, take note: there are a number of benefits to running an embassy out of an historic mansion on Fifth Avenue. First, look around: you’re in an historic mansion on Fifth Avenue! Second, go upstairs: you’re still in that same historic mansion, on the same Fifth Avenue! Third, take stock of the fact that, because you don’t pay rent, you can kiss off market forces and open any business you’d like … in your historic mansion on Fifth Avenue!

Antonin Baudry, the cultural counselor for the French Embassy, had such a realization a few years ago. For more than sixty years, the embassy has made use of the Payne Whitney House, an opulent Italian Renaissance–style home erected from 1902 to 1906 at Fifth Ave. and 79th St. It seemed a shame, he thought, to deny passersby the chance to see its tongue-lollingly gorgeous interior. It also seemed a shame that New York had lost its last French bookstore, the Librairie de France, in 2009 …

You may see where this is headed. Baudry and his staff are at this moment putting the finishing touches on Albertine, a new French bookstore housed in the embassy—it opens Saturday at eleven A.M. When I visited yesterday, Baudry showed me around its impressive two floors, which had already achieved—though the ladders and drop clothes were still in evidence, and the painters were still painting, the burnishers still burnishing—an enviable blend of new bookstore smell and old building smell. It resembles a magnificent private library of the sort you’d expect to find in a turn-of-the-century estate.

Albertine takes its name from “the beautiful, omnipresent and unknowable female character in Marcel Proust’s classic In Search of Lost Time.” Its two floors will accommodate fourteen thousand books—some in French, some in English, many unavailable anywhere else in the city—from thirty Francophone countries. The shop includes a children’s section, a rare-books room, and a preponderance of reading nooks—the nook having reached its apotheosis around the time the Payne Whitney House was built. On its ceiling is a carefully painted night sky in the style of a Renaissance fresco.

Since raising enough money to make rent isn’t an issue, there’s no pressure to buy anything at Albertine, and Baudry encourages future visitors to linger, and to read, for as long as they’d like. To inaugurate the store, he and Greil Marcus have curated a festival of events beginning next month: among the many writers and thinkers set to appear are Emmanuel Carrère, Mary Gaitskill, Percival Everett, Matthew Weiner, A. O. Scott, and Marjane Satrapi, with discussions of topics as varied as de Tocqueville, Coco Chanel, censorship, mathematics, and The Wealth of Nations.

When our Paris editor, Susannah Hunnewell, interviewed Baudry earlier this year about his graphic novel, he mentioned a bit about Albertine and the embassy:

It’s designed to look like a grand private library. No commercial displays or aggressive lighting. You can buy books, but you can also just sit on the sofa and read them. Part of the concept is to create a French-American venue for international debate, to invite the most original writers in the U.S. and Europe to discuss art and finance and politics ... It’s the last building Stanford White designed. Actually, he was shot dead by a jealous husband while he was working on it. It was a gift from Colonel Whitney to his nephew, who was getting married. The Whitney family lived there for thirty years, then sold it to a German actress. Then Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French ethnologist, was appointed by General de Gaulle as the first cultural counselor to the U.S. He saw the building and convinced France to buy it.

Credos

From the cover of Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love.

On this, the occasion of T. S. Eliot’s birth, it’s interesting to revisit (or, I should say, visit—if you didn’t happen to be around in 1965) his Times obituary. Especially this bit:

Lacked Flamboyance

In his later years he had an office in London in the publishing house of Faber & Faber, of which he was a director. There he carried on his business, writing letters and articles, somewhat like the clerkish type he resembled.

In appearance he was then, as he was in early life, a most unlikely figure for a poet. He lacked flamboyance or oddity in dress or manner, and there was nothing of the romantic about him. He carried no auras, cast no arresting eye and wore his heart, as nearly as he could be observed, in its proper anatomical place.

His habits of work were equally “unpoetic,” for he eschewed bars and cafes for the pleasant and bourgeois comforts of an office with padded chairs and a well-lighted desk.

Talking of his work habits, he once said:

“A great deal of my new play, ‘The Elder Statesman,’ was produced in pencil and paper, very roughly. Then I typed it myself first before my wife got to work on it. In typing myself I make alterations, very considerable ones. But whether I write or type, composition of any length, a play for example, means for me regular hours, say 10 to 1. I found that three hours a day is about all I can do of actual composing. I could do the polish perhaps later.”

Eliot’s dress was a model of the London man of business. He wore a bowler and often carried a tightly rolled umbrella. His accent which started out as pure American Middle West did undergo changes, becoming over the years quite British U.

The U was complete and unfeigned. “I am,” he said stoutly, “an Anglo-Catholic in religion, a classicist in literature and a royalist in politics.”

Even so, his ascetic austerity drew the line at gin rummy, which he delighted to play of an evening. He also kept a signed photograph of Groucho Marx, cigar protuberant, in his study at home.

These touches lend credence to Eliot’s attempts in later years to soften some aspects of his credo. His religious beliefs, he asserted, remained unchanged and he was still in favor of monarchy in all countries having a monarch, but the term classicism was no longer so important to him.

By “British U,” the Gray Lady is presumably referring to the terms introduced by the linguist Alan S. C. Ross in 1954 and popularized by Nancy Mitford in her anthology Noblesse Oblige. U stands for upper class, a very certain type of it. In her joking taxonomy, Mitford explains how to differentiate the true toff form the non-U aspirant: carrying umbrellas, saying couch or dentures or perfume, for instance.

The book was a joke, kind of, even when Mitford—and Evelyn Waugh and John Betjeman, who contributed—wrote it, delighting in obsolescence and cartoonish snobbery. But then, Mitfordania has always been rooted in a conscious, willful nostalgia for the arcane, the eccentric, and, of course, the country house. The last living representative of this specific brand of U, Deborah, the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire—also known as Nancy’s little sister, Debo—died this week at the age of ninety-four. Beloved by Anglophiles—and any fan of Nancy’s novels, in which Deborah appears as one of the composite little sisters—she was celebrated in later life as the savior of Chatsworth House, the Derbyshire seat of the Cavendish family. Google her obituaries and phrases like end of an era are frequently to be found.

Just what said era had to do with most of us American readers is an open question. The Duchess of Devonshire herself was frank about the challenges of maintaining a great house in the modern era, and the necessary pragmatic diminutions in lifestyle; Downton Abbey this was not. But as I write this I am sipping from a mug commemorating Pursuit of Love, another Nancy Mitford novel; as Eliot said, “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.”

In Search of the Lost Trail

Remembering Le Grand Meaulnes on the centenary of its author’s death.

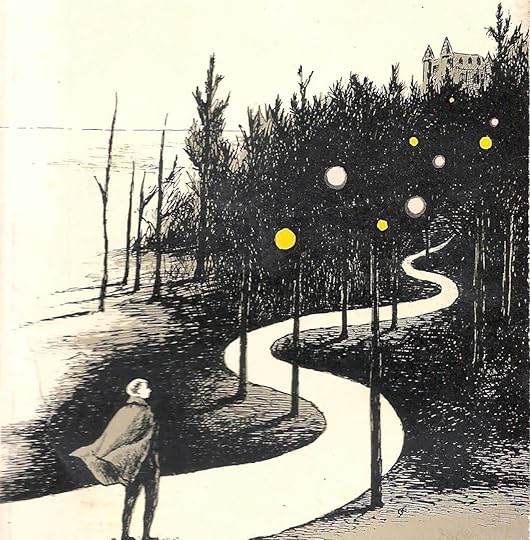

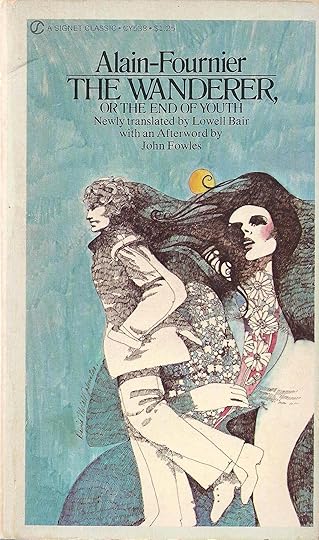

Detail from Edward Gorey’s cover of the Anchor 1950s edition of Le Grand Meaulnes, dubbed The Wanderer.

“There is no doubting the classic status of Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes,” the novelist Julian Barnes wrote in the Guardian in 2012, having revisited the novel in his sixties to see if it retained its “youthful enchantment.” “A poll of French readers,” he noted, “placed it sixth of all twentieth-century books, just behind Proust and Camus.”

Those two are widely known to English-speaking audiences, and yet Le Grand Meaulnes and its mysterious-sounding author are not. I asked twenty self-admitting Francophile friends if they had ever heard of Fournier; most of them hadn’t. It doesn’t help that the novel—the only book Fournier published in his lifetime—has had at least seven different titles in English: The Wanderer (sometimes with the subtitle Or, The End of Youth), The Lost Domain, The Land of Lost Contentment, The Big Meaulnes, The Magnificent Meaulnes. The most recent translation, from 2007, is called The Lost Estate, with Le Grand Meaulnes in parentheses.

Originally published in 1913, the novel only barely predated Fournier’s death on the front lines in the first months of World War I, on September 22, 1914—a hundred years ago this week. Fournier was, at twenty-seven, one of the war’s first literary casualties. “His unit strayed accidentally behind the loose German lines in a forest of the Hauts-de-Meuse,” the novelist John Fowles wrote in an afterword to the book in the early seventies. “They found themselves trapped at the edge of a beechwood. The Frenchmen charged. Lieutenant Fournier was last seen running toward the Germans, firing his revolver. His grave is unknown. He was presumably buried by the enemy.”

Having recently become a parent, I’ve started to cobble together a young-adult reading list to give to my son one day—which is what led me to Le Grand Meaulnes, with its affecting treatment of lost innocence and its finely tuned, fairy tale–like depiction of the “twilight world between boyhood and manhood.”

That twilight is appealing to me—I can imagine myself as one of the characters, inching along as the story unfolds. Much like Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, to which it’s invariably compared, Le Grand Meaulnes is dreamy and at times overly romantic as it describes one boy’s lost love for a girl he’ll likely never have. That boy is seventeen-year-old Augustin Meaulnes, a mysterious “boarder” of modest means and background who arrives one day in the small provincial town of Sologne, in the heartland of France. He immediately captures the attention and enthusiasm of his classmates, especially his host family’s son, Francois Seurel, who narrates the novel and so resembles Gatsby’s Nick Carraway; one might be tempted to see him as a stand-in for Fournier himself, but if he is, then so is Augustin Meaulnes.

That twilight is appealing to me—I can imagine myself as one of the characters, inching along as the story unfolds. Much like Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, to which it’s invariably compared, Le Grand Meaulnes is dreamy and at times overly romantic as it describes one boy’s lost love for a girl he’ll likely never have. That boy is seventeen-year-old Augustin Meaulnes, a mysterious “boarder” of modest means and background who arrives one day in the small provincial town of Sologne, in the heartland of France. He immediately captures the attention and enthusiasm of his classmates, especially his host family’s son, Francois Seurel, who narrates the novel and so resembles Gatsby’s Nick Carraway; one might be tempted to see him as a stand-in for Fournier himself, but if he is, then so is Augustin Meaulnes.

Le Grand Meaulnes remains, despite its age, superbly modern, and especially charming for young men. Meaulnes—whom Fournier refers to as “Admiral Meaulnes” at times, imbuing him with a kind of authority—has a Ferris Bueller–ish quality in that he’s almost astonishingly likable; he becomes the center of attention as soon as he arrives on the scene. His fellow students seem to hang on his every word.

On a misguided attempt to pick up his host family’s grandparents by carriage at a nearby train station, Meaulnes disappears into a forest. When he reappears a few days later, he recounts a fantastic tale: On his journey, he says, he stumbled on a majestic, if dilapidated, French chateau, which hosted a magnificent costume ball. It was there that Meaulnes met the girl of his dreams, Yvonne de Galais, who lives in the house with her brother, Frantz, and their widowed father.

When Meaulnes returns to school, he’s a changed young man. He becomes restless in his attempts to regain the lost chateau, and Yvonne with it. “That breath of fresh air coming from the deserted playground,” Fournier writes, “the bits of straw which could be seen clinging to Admiral Meaulnes’s clothing, and above all the look he had as a traveler, tired, hungry, but thrilled by wonders, all gave us a strange feeling of pleasure and curiosity.”

From there, the narrative gets a bit too cooperative: another mysterious boy shows up in town, and he turns out to be Yvonne’s brother, Frantz, in disguise; he’s reeling from a broken engagement. Meaulnes, fearing he’s lost Yvonne forever, then flees to Paris to find her, leaving Seurel in his wake to piece together the backstory, still untold.

From there, the narrative gets a bit too cooperative: another mysterious boy shows up in town, and he turns out to be Yvonne’s brother, Frantz, in disguise; he’s reeling from a broken engagement. Meaulnes, fearing he’s lost Yvonne forever, then flees to Paris to find her, leaving Seurel in his wake to piece together the backstory, still untold.

Toward the end of the book, in Fournier’s crescendo, it’s Seurel, not Meaulnes, who eventually finds Yvonne. He reunites her with Meaulnes and they’re finally married, but that’s not the happy end—a few days after the wedding, Meaulnes, feeling he owes a debt of gratitude to Yvonne’s brother for unexplained reasons, flees once again, this time on a quest to help Frantz find his lost fiancée, leaving Seurel to serve as kind of a surrogate husband to Yvonne. Meaulnes is like the front man of an indie-rock band who walks out on his honeymoon to tour the West Coast instead of chilling with the girl he’s been dreaming about for years.

Yvonne remains in the “lost chateau” alone. Though the book never describes any kind of sex or physical intimacy, she gives birth to Meaulnes’s child and dies two days later. They never see each other again.

Seurel inherits the house and sits idly by waiting for Meaulnes to return. He stumbles upon a handwritten secret journal—composed in a student’s composition book—which fills in the blanks of a rather convoluted story. Turns out Meaulnes felt so guilty about Frantz’s lost fiancée because, years earlier, before he knew Frantz or his sister, Meaulnes had unwittingly romanced Frantz’s fiancée.

In the end, it turns out that the only one left holding an empty bag is Seurel. After Yvonne’s untimely death, he delivers Meaulnes’s daughter. “The father lifted his daughter on high,” he says in the closing paragraphs, “jumping her up on his outstretched arms, and looked at her with a kind of smile. She was pleased and clapped her hands … I had stepped back a little to see them better. Rather let down and yet wonder-struck, I realized that the little girl had at last found in him the playfellow she had been dimly expecting … Meaulnes had left me with one joy; I felt that he had come back to take it away from me. And already I could imagine him at night, wrapping his daughter in his cloak and setting out with her for new adventures.”

In the end, it turns out that the only one left holding an empty bag is Seurel. After Yvonne’s untimely death, he delivers Meaulnes’s daughter. “The father lifted his daughter on high,” he says in the closing paragraphs, “jumping her up on his outstretched arms, and looked at her with a kind of smile. She was pleased and clapped her hands … I had stepped back a little to see them better. Rather let down and yet wonder-struck, I realized that the little girl had at last found in him the playfellow she had been dimly expecting … Meaulnes had left me with one joy; I felt that he had come back to take it away from me. And already I could imagine him at night, wrapping his daughter in his cloak and setting out with her for new adventures.”

* * *

“In some respects,” Fredrika Blair points out in her introduction to the 1950 Anchor edition, “Le Grand Meaulnes resembles Kafka’s fantasy, The Castle. Both are allegories. The Castle is an allegorical account of the search for heaven and Le Grand Meaulnes of the search for happiness. In both of them there is the same combination of dreamlike vision and everyday detail.”

Fournier’s good friend and fellow writer Jacques Riviére, who would go on to found the immensely important La Nouvelle Revue, warned him against “falling into sentimentality,” to which Fournier replied, “I think that sentimentality is above all sloppy writing. My credo in art: childhood. To be able to reproduce it without any childishness—its depth touches on the mysterious.” The overwhelming sense that anything is possible—the optimism of youth—holds the book’s somewhat contrived plot together, and redirects the reader’s attention from unbelievable flights of fancy to the endless potential of adolescence.

Perhaps the reason Le Grand Meaulnes is a rite-of-passage novel in France today is more elementary than most of the criticism surrounding it would have you believe. The novel’s takeaway, for me, is a don’t-look-back realization most teenagers have, at some point, wherein they recognize that everything they thought was the best—or the most important, or the worst thing ever—was actually mundane, trivial. That’s a sobering feeling, even when it comes to the vagaries of young love, the ache that feels like a hole in the stomach.

Perhaps the reason Le Grand Meaulnes is a rite-of-passage novel in France today is more elementary than most of the criticism surrounding it would have you believe. The novel’s takeaway, for me, is a don’t-look-back realization most teenagers have, at some point, wherein they recognize that everything they thought was the best—or the most important, or the worst thing ever—was actually mundane, trivial. That’s a sobering feeling, even when it comes to the vagaries of young love, the ache that feels like a hole in the stomach.

Or maybe it’s the book’s sexlessness that makes it cling to the adolescent heart. Adam Gopnik of The New Yorker draws attention, in his introduction to the most recent edition, to a point that helps explain why Le Grand Meaulnes endures more than one hundred years later: “The intricate and seductive fabric of romance as Fournier made it for himself there is some sheer fear of sex. We have a sense, reflecting on Fournier’s life and art, that what is being fabulized is in part an ambivalence about sexual intercourse; we want to sleep with the girl in a fairy-tale castle and still live there, remain children and get laid at once … We can no more imagine the act of sex that produces the child in Le Grand Meaulnes than we can imagine Gatsby penetrating Daisy.”

J. C. Gabel is a writer, editor, and publisher living in Los Angeles. He grew up in Chicago.

Ray Bradbury on Your Wall, and Other News

In Ray Bradbury‘s art collection: Ray Bradbury. Photo via io9

Ray Bradbury’s art collection is at auction, and it’s full of science-fictional wonders: moonscapes, fabulist spacecraft, fire-belching dragons, robot dinosaurs eating robot men, and Bradbury himself, inter alia.

Karl Miller, the founding editor of The London Review of Books, has died at eighty-three. His former colleague Andrew O’Hagan called him “perhaps the last of the great Bloomsbury men … Of course, there are brilliant writers and editors now, but they live in a world where the squeeze on literary values and on books programs, on high culture and carefulness, is fearsome and degrading. Karl Miller worked in spite of the market, and he enriched the intellectual life of the country in a thousand ways.”

Rediscovering Alain Robbe-Grillet’s first six films, which are now easier to stream than ever: They’re “psychosexually nutty meta-movies that eat their own tails so lustily they make Godard’s contemporaneous work look orthodox … [They’re] tasteful affairs, gorgeously shot and structured, like his fiction, around narrative ellipses and absences, mysteries that can never be solved, enigmas that defy time and reason. They’re also jam-packed with nude actresses and erotic posturing … ”

A salute to Futura, the typeface that’s been to the moon (and in every Wes Anderson film): “Futura represents the rational utopia of progress, where everything not only works well, but looks good doing it … Futura was the future we dreamt of in the past, and, in part, the future we achieved.”

On the celebrity of the Mitford sisters: Were these “beautiful, wayward young women”—the youngest of whom died yesterday—the Kardashians of their day? “Although it’s a stretch to imagine any of the Mitford sisters making a sex tape or promoting an ice cream called Va-Va-Va-Nilla, the nature of their fame is similar. Born from a fascination with the rich and beautiful, and the ability we are granted through newspapers or internet to live vicariously through these people, to share their adventures, and be scandalized by their mistakes, the fascination with which we view the Mitfords and Kardashians is one and the same.”

September 25, 2014

Design for Living

At the age of fifteen, I embarked upon a get-rich-quick scheme that I incidentally felt was a really valuable public service. I planned to make audio recordings of the various midcentury career romances I’d collected, and then to somehow duplicate them, sell them to a clamoring public, and make my fortune. Of legal issues, recording technology, and demand, I knew nothing. But I was armed with my dad’s tape recorder, a dream, and a copy of Designed by Stacey.

At the age of fifteen, I embarked upon a get-rich-quick scheme that I incidentally felt was a really valuable public service. I planned to make audio recordings of the various midcentury career romances I’d collected, and then to somehow duplicate them, sell them to a clamoring public, and make my fortune. Of legal issues, recording technology, and demand, I knew nothing. But I was armed with my dad’s tape recorder, a dream, and a copy of Designed by Stacey.

I’ve written about Marcia Miller’s 1967 masterpiece before, for Jezebel, and I stand by my endorsement of it:

What it lacks in accurate depiction of the fashion industry, it more than makes up for with wild plot twists, vague anti-Semitism, and amazing sixties clothes. Indeed, I would go so far as to call DbS the gateway drug of career romances: lite on career, heavy on bizarre, and one hell of a page-turner.

My fifteen-year-old self knew it would be catnip to the buying public. Our story and my tape begin with Stacey Harrison’s triumphant return to San Francisco—and her newly married, successful architect father, Con—after studying design in Paris. We are immediately treated to a description of our heroine’s “slim height, the smooth and shining chestnut hair, swept high on her head above large, dark-lashed gray eyes … the tawny skin with pale gold freckles across the bridge of the tipped nose, and the well-shaped mouth parting over even white teeth.”

Although dismayed by the chilliness of her feline new stepmother, Kay, Stacey happily settles into a brand-new apartment complex, The Towers, “a great spire of concrete, steel and glass” with “an arcade with excellent shops, maid service and transportation to any point in the city.”

She immediately lands a coveted position in the exquisite atelier of the couturier Madame Ninon, sketching designs for customers. Madame Ninon has a sullen, intriguing nephew called David Maclean who stalks around being furious and snubbing Stacey; later we learn this is because he was abandoned by his mother and is afraid to love. This is how we know he is softening towards Stacey: when he runs into her at a seafood restaurant on Fisherman’s Wharf (she is sporting a camel coat), he says smolderingly, “May I suggest the Captain’s Favorite?”

As to Madame, she is the closest thing we see to an actual professional. “Line is everything,” she says. “A good couturiere can visually translate a woman into many different women, and this is done by line, not ornamentation. A couturiere must be like a writer and say what must be said in as few words as possible.”

In due course, Stacey’s natural talent is discovered. She designs a gown that Madame Ninon adores; that gown is given its own launch party, but Stacey shows up to find a competitor has stolen the design; then she finds out her father has unexpectedly died. There are a couple of other characters, too—this decoy beau called Kirk and an enigmatic actress, but they don’t have much to do.

It took me quite some time to make my recording, although I did it in a single take. I was determined to bring to life Stacey’s cool elegance, Madame Ninon’s fire, David Maclean’s inexplicable fury. I tried to make Kay’s accent confusing, so as to forecast the reveal of her hidden background. I didn’t actually plan to market the product with my own vocal talents—I had vague plans of hiring actors—but I figured this prototype would net me what seed money I needed for recording studios, cover art, and other vague essentials. And secretly, I thought my version was pretty good.

I invited my friend Ajana over and sat her down to listen to my tape. For maximum awkwardness, I sat next to her while it played. After the first few chapters, I turned it off. “What do you think?” I demanded.

“Well,” she said carefully. “All the voices sound … kind of the same.”

I was totally deflated, and stuck the tape in my desk. I found it this week. I sound like a disgruntled member of the Lollipop Guild in a wind tunnel, albeit sometimes with an unintelligible French accent. “Designed by Stacey: DEMO” I wrote on the cassette’s adhesive label. I’m not sure it would survive a copyright lawsuit.

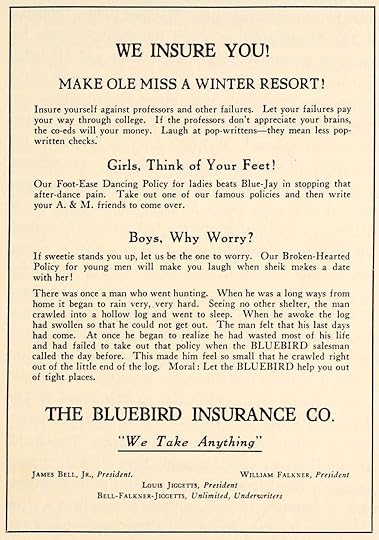

Insure Yourself with Faulkner

From December 1921 until October 1924, William Faulkner enjoyed a famously disastrous tenure as the University of Mississippi’s postmaster. He’d arrive late, leave early, play bridge, and work on his fiction—all while losing mail or simply throwing it away. (“I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp,” he wrote in his brief, pungent resignation letter.)

During these years Faulkner wrote regularly for The Mississippian, the school newspaper. Of his contributions, the strangest and most apocryphal is the mock-advertisement above, for the Bluebird Insurance Co., which offered to indemnify students “against professors and other failures.” It goes on to discuss feet, heartbreak, and hollow logs, none of them very coherently.

Faulkner, minus the u, is listed as one of the company’s three presidents, and apparently it’s never been clear whether he helped write the ad or was named without consent. Whatever the case, in the weeks and months to follow, more ads for Bluebird appeared in The Mississippian and the Ole Miss annual. One of them took a (self-deprecating?) jab at Faulkner’s job performance: “It is a gross injustice to say that President Falkner has permanently retired in the Post Office. He merely takes temporary naps—during business hours.”

Carvel Collins tells the story more completely in the introduction to his William Faulkner: Early Prose and Poetry (1961):

On January 11, 1924, [The Mississippian] carried a large, humorous “advertisement” for a Bluebird Insurance Company which was dedicated to the happiness of students because it would protect them in their college courses by insuring them “against professors and other failures.” This advertisement and those which followed it purported to have been purchased by a company composed of three men: a student who had just returned from England where he had been at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar; one of Faulkner’s post office assistants, who later would become postmaster when Faulkner resigned; and Faulkner. Each was listed as a “president” of the company.

The published accounts of Faulkner’s life which mention the Bluebird Insurance Company seem to have assumed without question that Faulkner invented and developed this joke. One cannot with assurance label that interpretation wrong, but there is the possibility that much—or all?—of this series of advertisements originated in the office of The Mississippian and that Faulkner and, perhaps, the other two men were drafted as “presidents” without their consent or knowledge.

[…] It seems doubtful that [Faulkner] would strongly have favored publishing among the defenses of the Company in its advertisement of February 15 such an item as this: “It is a gross injustice to say that President Falkner has permanently retired in the Post Office. He merely takes temporary naps—during business hours.” Faulkner, whose sense of humor has clearly demonstrated that it includes himself, may have taken part in this series of advertisements, which did not end until many months later with a full-page notice in the Ole Miss annual; but until firmer evidence appears either way, admirers of his fiction should be kindly allowed at least to assume that if Faulkner did voluntarily help work up these Bluebird notices he did not write the more flat-footed parts of them, did not favor stretching the joke over such a long time, and had nothing whatever to do with the news article in the February 15 Mississippian which announced that the next day the campus would start “The Bluebird Game,” in which “some popular young man,” secretly the Bluebird, would “carry a striped letter” to deliver “to the first coed” who happened to ask whether he was the Bluebird. “The fortunate young lady” would receive a ticket to the movies and a Bluebird insurance policy. The first game was to be “solely for the coeds. The next solely for the eds.” “Isn’t a ticket to the show worth asking the question? Try it. You’ll find it fun. Play the Bluebird game.”

Hovering Hippie: In the Gallery with Gary Panter

I’ve twice visited Gary Panter’s studio, a large room tucked away on the third floor of his house in Brooklyn; the table at which he works—he lays his canvases flat to paint—sits roughly near the center of the room and is surrounded on all sides and from above by evidence of his many and various areas of work: painting, drawing, comics, music, design, printmaking, and sculpture. All of his art is of a piece, so in his studio it’s especially difficult to get a sense of just one aspect of it. Rather than report on Panter’s recent paintings from there, I proposed we meet at Fredericks & Freiser, where “Dream Town,” his show of new work, went on view earlier this month. Most of the paintings depict figures excerpted from their original sources and painted flatly, as though collaged, onto either monochromatic or expressionist backgrounds. The pristine walls of the gallery make it easy to focus on individual paintings and to see the connections between them. Still, in his paintings, as in much of his art, Panter converses with an estimable range of cultural subjects and styles, so, naturally, we ended up talking about far more than just painting.

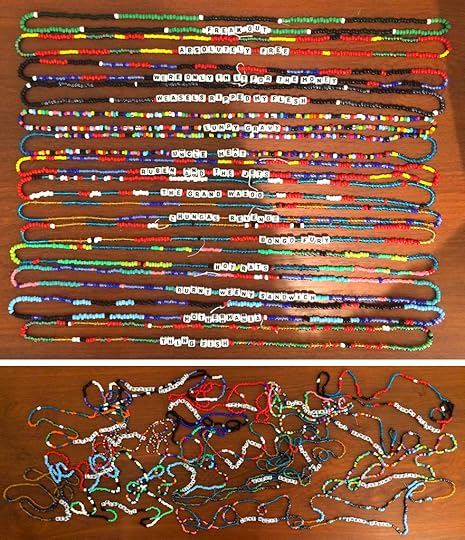

From top: Frank Zappa List, 2014, glass seed beads, plastic letter beads, nylon string, dimensions variable. Ed Sanders List, 2014, glass seed beads, plastic letter beads, nylon string, dimensions variable.

The beads in rows are Frank Zappa—the Mothers of Invention actually, album titles. Zappa was orderly, methodical. The others are Ed Sanders, fragments from his books. There are phrases from records by the Fugs, and he wrote a great parody novel about the hippies in the Chicago riots called Shards of God, so a lot of these are word fragments from that—“smelp troll,” “hovering hippie.” I’m also working lists of Ballard, Burgess, and other people. This is just a preview of my hippie project.

The whole project is personal. It’s a reflection of when I first went into a head shop in 1967 or ’68 on a family vacation to California. I wanted to be a hippie but couldn’t be a hippie—I was part of the Church of Christ. I fought with my dad all the way to California for the control of the radio knobs, because I was trying to get California stations. We got to the little town where my cousins lived—they’d moved from Oklahoma, where they’d lived super rustic, and now they were in Shasta—and there were hippies in town. We went to the hippie shop, and there were real, smelly hippies in there. Girls silk-screening, beading, a guy playing flute, and everything in the room was dark and kind of dank. We went next door, to a record shop, and they had walls of every psychedelic record I had never heard of. I drove my parents crazy until they let me buy a few, which I took back to Texas. But the sixties went really wrong in a lot of ways, so this is just hippie idealism.

I’m interested in trying to recapture what the hippies could have done had they not hit the consequences of free love, heroin, and speed. Too many people trying to be in the same place.

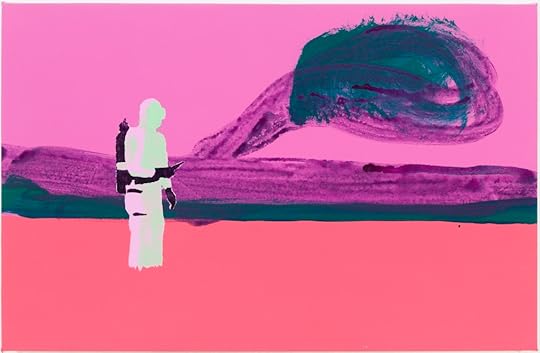

Fogger, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 23 x 35 1/2 in.

This is really a sixties painting. Trying to join the conversation of painting—modernism, anyway—is all about novelty, like “I do the stripe,” “I do the two floating, hovering clouds,” “I do the long, lashing brushstrokes.” And then, in the seventies, if you were a painter, everything had already been done. It was the death of painting. In the eighties, guys like David Salle and Julian Schnabel went back to the sixties. Most people try to go around their predecessors—I have to get around Peter Saul, for instance—but in the eighties, artists went right back to sixties problems. Everyone was trying to dig holes in the desert.

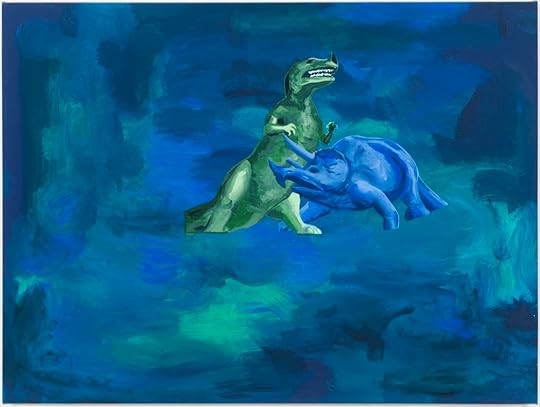

Lost World, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 35 1/2 x 47 1/2 in.

Making a painting is meditative, because I’ve already figured out my approach, I’ve already done a drawing, I know what it’s going to be. In that sense, there’s already a score written, so when I finally make a performance of it, I’m orchestrating the colors and the subtleties. For me, it’s always about the field and the subject. In the twentieth century there was a raw attempt to get past subject. They’d abstract it stylistically so it wasn’t recognizable—like Picasso at the beginning of the century. And then there was a kind of fusing of the figure with the ground, like in Dubuffet’s work—everything was flat.

I think Abstract Expressionism is like landscape painting. You take the subject away, you take all the figuration away, you’re still left with the emotions of the atmosphere. It’s an accidental or unstoppable association—patterns of weather, sky, water. In terms of figures, I’m trying to choose shapes that are interesting in themselves, and I put them in odd places so they become more interesting. Hopefully, that detracts attention from naming the figures, though your brain immediately thinks, Oh, two dinosaurs, or, Oh, a kid and a dinosaur. But if you’re making an abstract painting, you’re trying to dial that down.

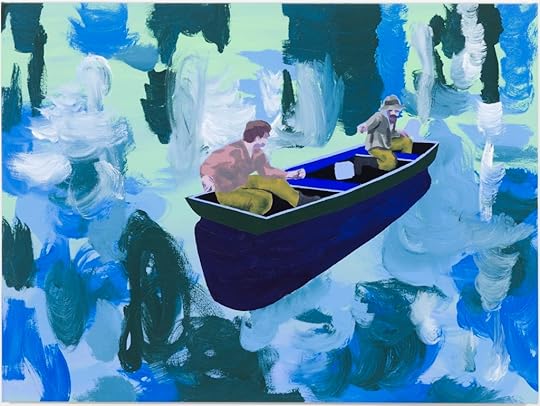

Loon, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 35 1/2 x 47 1/2 in.

Malcolm Morley said he chose stuff that meant nothing to him early in his career. It’s arbitrary—it’s just a racehorse or a ship. Then later, he starts painting children’s toys, and it seemed like his emotions were driving him. Some of the forms in my paintings are things that mean something to me—like the first dinosaur movie I went to or that my brother doesn’t believe in dinosaurs—but mainly they’re not that literal. The figures I’m looking for suggest a human moment, an interaction of attention. You don’t need to know the story behind the moment, only the feeling the scene creates. If you live with a painting, you see it for hundreds of hours, thousands of times, but most people see a painting for thirty seconds in a gallery, and past that, they get bored. So a painting has to do its job, whatever the artist wants that job to be.

I go through thousands of pictures, and hardly any of them will be in a painting. I did it last night—I looked at probably two thousand pictures and didn’t see anything I wanted to paint. Cartoons are usually telling a story. Paintings are more like moments or like poems, like haiku. You get it in a moment, if you get it.

Detante, 2013, acrylic on canvas, 22 1/2 x 35 1/2 in.

I want the edges to be straight up to a certain point. I have corrected some of the edges to make them more precise, but I wont just keep going until you can’t tell them apart. That’s not important to me. I’m interested in how you see it quickly and how it feels around you, like it has an orbit or something. This type of painting tends to be kind of cold, so I’m looking for a little bit of heat.

It’s hard to get the narrative out. If you see a duck, you start thinking duck stuff. Frank Stella once said in an interview that naked women and ducks are always trying to get into paintings but that he doesn’t let them in. But Peter Saul lets them all in—all the ducks and naked ladies. It’s a different approach, because everyone can’t be Frank Stella.

I’m looking for loose ends and things that are missing. There are artists who do one thing, like, say, Peter Max. He did his one thing and then everyone else started doing it—and everyone else became Peter Max. If you keep moving artistically, if you have a life on the road, so to speak, then you don’t have to care if people like it or don’t like it or are influenced by it, because really it’s about you being alive for a little bit of time and trying to do something with it. The quirky thing about these paintings is I know how to paint all kinds of paintings, but I have a crazy idealistic sensitivity of trying to feel my way toward the right paintings to do. I can see hundreds more paintings that I could do, but I’m waiting for a little bell to ring in my head, and I don’t know who rings it.

Hand of Gorgo, 2013, acrylic on canvas, 35 1/2 x 48 1/2 in.

I like the purple Gorgo painting a lot because I like the movie. It scared me when I was a kid. Gorgo was an English Godzilla movie, and they framed this Godzilla monster and they catch it and they put it in the circus, and it’s like a hundred feet tall, and he breaks out and gets lost in London and they’re shooting it and then its mom comes out and rescues it and she was like a thousand feet tall and she’s like, Come home, baby, and smashes her way back up through the ceiling and they’re gone. In the painting, that’s the baby’s hand coming out of the water. But that’s only important to me. Unless you were twelve years old in 1960, you didn’t have that experience. It’s not necessary information for appreciating the painting. What’s important to read in the painting are the colors, the shapes, the reflectivity off the torch in the water. If that wasn’t there, it’d be a lot less interesting. It’s a disruption that indicates a different space. It’s all an illusion, it’s not real, it’s on a stage, or a window. It’s painting. It’s an insecure business. Painting is really insecure stuff.

“Dream Town” is on view at Fredericks & Freiser through September 27.

Poems as Animals, and Other News

Roeland Savery, Paysage de forêt avec animaux, seventeenth century.

“I suppose I’ve read more dirty books than any man in New England, and I could make the biggest collection of erotica in this country if I wanted to.” An interview from 1930 with the censor for all of New England.

Christopher King, whose essay about Alexis Zoumbas appeared here on Monday, has a cameo in the Times Magazine: “King had invited me to visit him at his home in Faber, Virginia, where he keeps his own massive collection of 78 r.p.m. records, decaying discs that could only be experienced there, in person. He asked me what I might like to hear, and when I hesitated, he suggested Zoumbas … in Epirus, King said, these songs live and die in the looks and handshakes and embraces exchanged in their presence.”

When Freud, who died seventy-five years ago, was diagnosed with a very malignant form of cancer, he said he wanted to “disappear from the world with dignity,” which meant enlisting his doctor, Max Schur, to euthanize him. “All this was said without a trace of emotionality or self‑pity, and with full consciousness of reality.”

“Ted Hughes didn’t just write a lot of poems about animals—about pikes and jaguars and thought-foxes. He thought of poems as animals. ‘They have their own life,’ he wrote in an essay in 1967, ‘ … and nothing can be added to them or taken away without maiming and perhaps even killing them.’ ”

An Arizona law against “revenge porn” has the state’s booksellers concerned: it “could be applied to any person who distributes or displays an image of nudity—including pictures that are newsworthy, artistic, educational, or historic—without the depicted person’s consent, even images for which consent was impossible to obtain or is difficult to prove … ‘There are books on my shelves right now that might be illegal to sell under this law. How am I supposed to know whether the subjects of these photos gave their permission?’ ”

September 24, 2014

The Opposite of Icarus

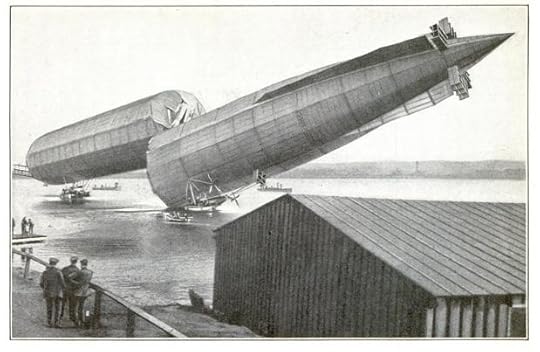

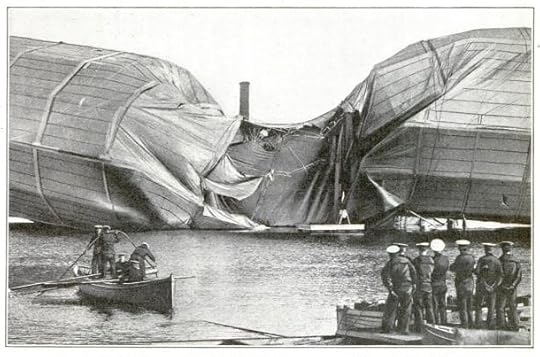

The wreck of the Mayfly, 1911.

Today in history: the dreams of British steampunks and dirigible enthusiasts were sundered like so many feet of duralumin. On September 24, 1911, His Majesty’s Airship No. 1, the rigid, phallic Mayfly, met its demise. If you don’t hear of this incident as often as you do, say, the Hindenburg disaster, it’s because (1) no one died, (2) nothing caught on fire, and (3) nothing fell to the ground; the Mayfly was torn in twain before she ever left the ground. All it took was a strong gust of wind and a bit of human error. The accident happened just as the crew removed the ship from its hangar for testing, as the Airship Heritage Trust explains:

Disaster struck in the form of a sudden forceful beam-side gust, causing the ship to lurch, just clearing [its] shed but [rolling] onto her beam ends. She righted and was then pivoted so her nose would point back out to the dock when there were cracking sounds amidships and she broke in two. She started to rise in an inverted V formation, but the crew in the gondola dived overboard, and the stern flew up into the air.

The damage was extensively photographed, and there’s something heartbreaking in the images—it enables a strange form of rubbernecking. Snapped in two, the ship looks impossibly frail, almost like an elongated box spring, and of dubious airworthiness. (Though it must be said that it floats quite nicely.) It was just over five hundred feet long, and it weighed forty-four thousand pounds. Its cruising speed was only estimated at forty-two miles an hour.

The wreck widened the gulf between Britain and Germany’s airship programs—by 1913, Germany had a fleet of seventeen zeppelins and the Brits had only two. That year, Winston Churchill had a nice zinger for the House of Commons:

Altogether, compared with other navies, the British aeroplane service has started very well … I have a less satisfactory account to give of airships. Naval airship developments were retarded by various causes. The mishap which destroyed the Mayfly, or the Won’t Fly, as it would be more accurate to call it, at Barrow, was a very serious setback to the development of Admiralty policy in airships.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers