The Paris Review's Blog, page 663

September 15, 2014

Natty Bumppo, Soviet Folk Hero

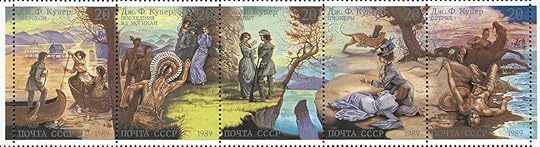

The Soviet Union’s 1989 series of James Fenimore Cooper stamps. Click to enlarge.

I was perplexed to learn that the Soviet Union, in its waning days, produced a series of five vivid postage stamps devoted to James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. It seemed as if some lazy Soviet bureaucrat must’ve made a mistake. Why, after all, would the USSR want to commemorate some of the foundational texts of American lit, especially when Natty Bumppo stands as a paragon of rugged individualism? In other words, how had one of our folk heroes found an audience in a place where he should’ve been reviled?

Sandra Nickel, an author of young-adult novels, got the answer from her daughter’s Russian godmother, whose youth was apparently filled with totally authorized American classics:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper, The Headless Horseman: A Strange Tale of Texas by Thomas Mayne Reid. Almost every Russian child had read these by the age of twelve—and read them more than once.

I am sure the Soviet state approved these books because of their propaganda value. Put together, these three volumes could portray Americans as slave-owning destroyers of Native Americans, who are bigoted against Mexicans. Racists, across the board, in other words.

Instead of finding the disgusting evidence of prejudice and imperialism, though, young Russian readers tended to see the novels as ripping good yarns, so much so that their characters were inducted into public life:

What spoke to them were the emotions, the suspense, the adventure, the heroes, and the friendship … In fact, Cooper’s second name, Fenimore, by which he is more readily recognized in Russia, has become a byword for exciting adventures. Loved by even the young Lenin and Stalin, The Last of the Mohicans penetrated Russian society … As [the] poet Tamara Logacheva says, “The heroic image of a courageous and honest Indian—Uncas—noble and devoted to his vanishing traditions, became an example for imitation by many generations of young people.”

There you have it. You can imagine Gorbachev, his state verging on dissolution, adhering one of the Leatherstocking stamps to a letter—perhaps to Reagan or H. W. Bush—and smiling warmly at the visage of Natty Bumppo, his troubled mind allayed, for the moment, by dusty schoolboy memories of The Deerslayer.

What a Way to Go!

A hexagram of Constans II struck in the Constantinople mint, struck ca. 648.

Sometimes power changes hands. Sometimes, perforce, the change is violent. And sometimes, albeit rarely, it involves a Byzantine emperor who’s assassinated in the bathtub, where his servant bashes his brains in with a silver bucket.

Such is the fate, putatively, that befell Constans II on September 15, 668, unless it befell him on July 15, 669, which is also eminently possible. As a historian on Reddit’s AskHistorians recently explained, “there is basically only one source for this, the eighth-century Theophilus of Edessa, who wrote a chronicle whilst serving the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. This work is now lost, but it was used by several later chroniclers, including the more well-known Theophanes from the ninth century.” Said historian goes on to quote an account by the tenth-century historian Agapius:

When Constans was in the bath, one of his attendants took a bucket, mixed in it mallow and soap, and put this on Constans’s head. While the latter’s eyes were filled with the mallow and soap, so that he could not open them, the attendant took the bucket and struck Constans on the head with it, so killing him. He rushed out of the bath to escape and no one heard any more of him. The servants remained outside waiting for the king to come out, but when they had been sitting a long time and it was getting late and he still had not come out, they entered the bath and found him unconscious. They brought him out and he lived for that day, but then died having reigned for twenty-seven years.

In a paper on the era’s Roman-Arab relations, the Oxford historian James Howard-Johnston collates a number of sources to offer a slightly different account:

On the 15th of July 669, a senior courtier, Andrew, went with Constans II into the bathhouse attached to his palace in Syracuse. He was charged with carrying out the first vital act of a conspiracy which had been hatched in Constantinople two years or so earlier and which was subsequently worked up into a detailed plan, with the backing of the Caliph Mu‘awiya, in Damascus in the course of 668 … He began to wash Constans’s hair, working up a lather. Constans naturally shut his eyes, at which Andrew struck him hard with a silver bucket, fracturing his skull. Andrew then slipped away unseen. Constans died two days later.

Constans was visiting Syracuse, Sicily at the time—a rare move for an emperor from Constantinople. The motives behind his assassination are complicated, because there were any number of valid reasons for his unpopularity: he killed his brother, he persecuted a couple guys who ended up becoming saints, and rumor had it he was considering moving the capital of the empire to Syracuse. And so he wound up on the bucket list, as it were. (I’m sorry.)

One wonders how the story’s greatest detail—that the bucket was silver—came to be passed down through the ages. It seems too perfect to be true: an icon of wealth and power, destroyed in the prime of his life, at his most vulnerable moment, by blunt, precious metal. Or was it not precious enough? Gold is a softer metal than silver. Perhaps if Constantine had had his bath accessories done in gold, the trauma to his head wouldn’t have proved fatal.

What have we learned? Be nice. Do not commit fratricide or alienate future saints. Trust no one. Eschew silver. Bathe alone.

The Subtle Thief of Youth

The beginning of the end?

Yesterday I saw my first selfie stick. I had read of such things, but I’d never seen one in the wild. It was being wielded by an extremely chic Japanese tourist who held her iPhone at, well, stick’s length, her face shaded by a floppy-brimmed hat, a cigarette drooping from her lips. People tell me such sticks, or “Smart Phone Boom Arms,” are ubiquitous in other countries, and I’m sure they’re all over the place here, too—but it still seems to me that it would take a lot of chutzpah both to carry an implement so explicitly dedicated to the pursuit of narcissism and then to publicly voice-activate it for good measure. “They’re all over the Vatican,” reported one friend.

If you prefer a more private form of solipsism, may I suggest you search for your own first name on UrbanDictionary.com? The rabbit hole that led me to this was a long one—I was curious about the name Beryl, if you must know—but, shamefully, it ended in my finding such reader-supplied entries as:

sadie

A word that describes someone really cool, hawt, funny and apparently an awsome cook. She wouldn’t take shit from anyone, and tends to love kids named Mike.

That sadie kid is fucking awsome.

and

Sadie

A name for any beautiful girl with a great sense of humor. Sadie’s tend to be really funny and short. They are also smart and don’t take crap from anyone. A Sadie is a girl that you can’t get enough of and whenever you see her you can’t help but smile and watch as she smiles back. Her smile is also great. I happen to love a Sadie.

Boy 1: Hey, did you hear about that new girl? She is really beautiful and funny.

Boy 2: Duh, her name is Sadie.

Boy 1: Did you hear the Beatles have a song called “Sexy Sadie”?

Boy 2: Duh, all Sadie’s are sexy.

Hours of fun await you! Or at the very least, hours of regression.

Back when the Internet was young and dial-up was the order of the day, I made the mistake of looking up my first name; I remember not knowing what I was supposed to do with the Internet, or what was supposed to be so fun. Back then, one of the first hits was the site of a BSDM aficionado called “Sensuous Sadie.” I didn’t look my name up again.

And then in college, reading Milton, we learned about the origins of the word “sensuous,” and how the poet coined it specifically to avoid the sexual connotations of sensual. I thought, How dare she. And, Poor Milton. We didn’t yet have sad emojis.

Milton

Freakin awesome, real tight, someone who displays desireable characteristics ...

Man that dude is totally Milton.

The Well on Spring Street

America’s first great murder trial, and the mark it left on New York.

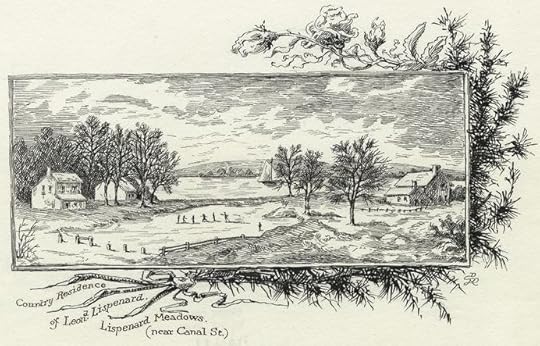

Archibald Robertson, Collect Pond–Bayard Mount, NYC, 1798.

Detested pit, may other times agree

With swelling mounds of earth to cover thee,

And hide the place, in whose obscure retreat

Some miscreant made his base design complete.

Thus, with oblivion’s wings to cover o’er

The spot which memory should preserve no more.

—Philip Freneau, A Collection of Poems, on American Affairs and a Variety of Other Subjects, 1815

On an unreasonably lovely August afternoon in SoHo—on Spring Street, to be precise, near where it meets Greene—I peered into the windows of a closed store, trying to see a way into what once might’ve been an alley. I was looking for a well that once captured the attention of the entire city: it was the scene of a murder most foul, a murder that pulled eighteenth-century New Yorkers into the bright, modern, terrifying future.

Gulielma Sands and Levi Weeks were planning to elope on the night of December 22, 1799. They lived in separate rooms at 208 Greenwich Street, a boarding house. Elma was going to sneak out and meet Levi somewhere private—this, at least, is what she told another resident at the house before she disappeared.

On January 2, two days into the new century, Elma’s body was found at the bottom of the Manhattan Well. The well took water from beneath Lispenard Meadow, the same water that filled the Collect Pond—a source of concern to New Yorkers, who associated standing water with disease. The meadow was a suburban respite from the crowded streets’ hustle and bustle of what we now call Tribeca: of the city but not really part of it. It was perfect for late-night sleigh rides, and sure enough, people living nearly half a mile away claimed to have seen Elma in a sleigh, between two men, on the night of the twenty-second. A week later, others noticed what looked like a lady’s muff floating near the top of the water.

* * *

If Elma and Levi are remembered at all today, it’s because he was arrested and tried for Elma’s murder and, with the help of a wealthy brother, retained the legal services of Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, who worked on the same side in what’s widely recognized as the first recorded murder trial in United States history.

The trial was about two objects, the first being Elma’s body. Was she pregnant? No. Was she a laudanum addict? Maybe. Was her neck broken, indicating she’d definitely been killed before being thrown into the depths of the water? Yes.

The second was the well itself. The defense team spent hours challenging witness statements, planting the seeds of doubt: Could this woman really see all the way to the well in the dark? Could that man really hear water splashing all the way from Broadway? Amid the pomp and circumstance of the eighteenth-century court transcripts, Hamilton in particular stands out—he questions experts and incidental witnesses alike with an electric slyness that would not feel out of place on television today. You can see where he’s going long before everyone else in the room gets there.

Elma’s body and the well in which it had been found served as twin omens for the rapidly expanding city. If beauty like hers—vibrant, hopeful, alive—could be mangled by the brute ugliness of murder, what beauty was safe? What mother, what caretaker could ever again let a beloved daughter out of the house alone past dusk? Every interaction between young people was tainted by the tragic drama of Elma and Levi. It was as if a pipe had burst and the muck of 1800 covered the clean streets of 1799. They got even filthier when, after a two-day trial and a five-minute jury deliberation, Levi was acquitted. While he was the obvious suspect, suspicion had fallen upon nearly every man Elma had known in New York, including the husband of her landlady (with whom she may or may not have been having an affair), and long after the jury asserted Levi’s innocence, public opinion was still largely divided on the subject. Levi, for his part, promptly skipped town—a prudent move, perhaps, but not great for instilling faith in the legal system.

A drawing of Lispenard Meadows by David McNeely Stauffer.

In a small town, the well might’ve become a legendary destination, frequented by tourists and sulky, rebellious teenagers, but lower Manhattan refused to stay put, and soon the only physical reminder of Elma Sands was covered up. In the 1820s, the once-bucolic meadow became a neighborhood full of upper-middle-class row homes, including one at 129 Spring Street, which is today the legal address of the well. By midcentury, it was a destination for shopping, entertaining, and sinning.

Just half a block down from the well, at no. 111 Spring Street, there existed a brothel kept by a Mrs. Hattie Taylor, described in an 1870 guide to whorehouses as “a third class house, where may be found the lowest class of courtezans. It is patronized by roughs and rowdies, and gentlemen who turn their shirts wrong side out when the other side is dirty.” During this period, 129 Spring was a shop run by a Mr. O. Spotswood, the peddler of an antidote to tobacco addiction, leading the modern reader to ruminate upon the kind of person who, in 1862, is both hooked on smoking and desperate (one dollar for a packet of five remedies!) to quit.

The prostitutes working in SoHo brothels embodied the fears of New York much in the way Elma Sands had decades earlier—they were taking something allegedly sacred, something that formed the basis of marriage and family, and twisting it. Day and night, they walked on a meadow-turned-city, water source-turned-murder site, woman-turned-cautionary tale.

But how many of those women (and men) had even heard of Elma? On April 18, 1869, the Times ran a paragraph-long item about the discovery, in a Greene Street alley, of the cover to a long-disused well, notable for being the site of a famous turn-of-the-century murder. The reporter mentions Hamilton, Burr, and Levi Weeks, but only the name of Elma, and only the barest details of the story, for “the old well was known to exist, but its precise location had passed from the memory of the ‘oldest inhabitant.’ ”

The well was forgotten again. Every few decades, it seems, someone might mention the case in passing, usually as an aside in a Hamilton or Burr story. There were a few ghost stories—Elma’s slim figure haunting the streets of SoHo, condemned for all eternity to reside at the bottom of the well as a reminder to girls not to sneak out with their sweethearts in the middle of the night. And there was, in 1870, an account of the trial published by a granddaughter of the boardinghouse keeper—emphatically it insisted upon Levi’s guilt, Elma’s beauty, and the fact that while the city might’ve covered the well with bricks and concrete and cast iron, it was still there.

After the tobacco cure shop closed, 129 became a German beer hall, and for a while after that it was nothing at all.

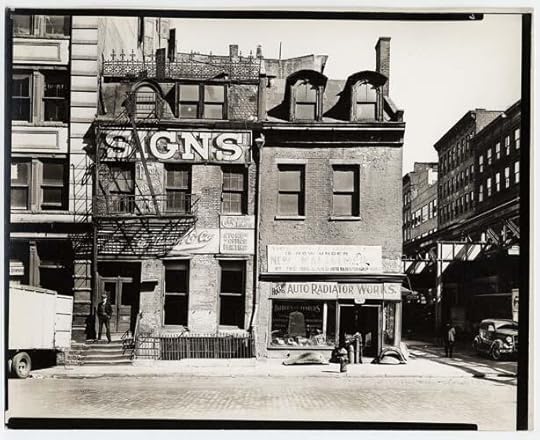

504-506 Broome Street in 1937. Photo via NewYorkologist

In 1957, the Times sent another reporter into SoHo to find the well. The area was deserted—the entertainment district of the mid-nineteenth century had been supplanted by industry, and the Belgian-block streets were still a few years from being claimed by artists and their associates. The cover was still there, of course, along with, the reporter assumed, the well itself.

The thing about burial is that unless you can convince the earth to do the work of decomposition for you, what’s put underground usually stays there. For a period in the late nineties and early 2000s, 129 Spring Street was a restaurant. The owners wanted more space for storage, so they excavated the cellar. Guess what they found?

As they told the Travel Channel—during one of those ghastly specials on Very Important Haunted Places that always feature ghosts who are both filled with rage and yet totally harmless—the well looked as though it hadn’t changed a bit since the eighteenth century. Looking at pictures, it’s taller than I expected, and sturdier. It’s sinister, maybe, or it just looks like a rebuke from two hundred years ago. How can you be eating sous vide salmon, I imagine it asking. Don’t you know what’s down here?

When I’m standing on Spring Street peering through the windows of 129, my heart isn’t in it. Were the restaurant still open I might try to identify myself as a historian, someone deserving of a trip to the basement to press my hands against the stone of the well, but the restaurant closed, and now at the corner of Spring and Greene, in the former Lispenard’s Meadow, sits the future location of CoS, the high-end offshoot of H&M. The store isn’t open yet, but I assume I won’t be able to talk my way into the basement, and if I could I’d probably find it filled with vaguely architectural jackets for the modern woman.

I want, as should be obvious by now, to think of the well as some sort of telltale heart, beating the narrative of sex and danger and death and fear into the air of the store, but H&M is a Swedish company, and one imagines them having an insurance policy preventing such nonsense.

* * *

The well as it was discovered beneath the restaurant.

One of my worst habits, I think, is refusing to acknowledge that anything is new, because, in fact, nothing is new. Walking in SoHo the other night, I loudly, and probably a bit boorishly, mentioned that before the neighborhood had hosted artists it had been a place of commerce—department stores almost outnumbered brothels—and so we may as well get used to it as such a place again. If I really wanted to be pedantic, I could’ve suggested tearing everything down and making the space a meadow once more; we could uncover the well and tell the story of Elma and Levi again, though I suppose in a sense we’ve never stopped telling it.

In 1957, when the Times reporter went downtown to stand on the well, or near it, or both, he took a cab back to the office:

The cab driver who had brought the reporter to that lonely spot wondered what it was that brought him to the alley. The reporter said, “Just checking on a murder; a girl was killed here.” The cabby said, “I think I read about it a coupla days ago.”

Angela Serratore is the deputy web editor at Lapham’s Quarterly.

The Fade-out Fades Out, and Other News

Photo: Holger Ellgaard

“When John Ashbery, the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, first learned that the digital editions of his poetry looked nothing like the print version, he was stunned. There were no line breaks, and the stanzas had been jammed together into a block of text that looked like prose. The careful architecture of his poems had been leveled … That was three years ago, and digital publishing has evolved a lot since then. Publishers can now create e-books that better preserve a poet’s meticulous formatting.”

Today in academic tiffs: One professor tried to publish a controversial essay avowing that Shakespeare’s works were written by Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Another professor offered a stern rebuke: “I simply find your reasoning, and your evidence, as unconvincing as those of Holocaust deniers, and other conspiracy theorists.” Finger pointing and harrumphing ensued.

Stop-and-frisk is more than just a widely reviled NYPD policy: it’s an opera!

Has pop music bid adieu to the fade-out? “The fade-out—the technique of ending a song with a slow decrease in volume over its last few seconds—became common in the 1950s and ruled for three decades. Among the year-end top ten songs for 1985, there’s not one cold ending. But it’s been on the downturn since the nineties, and the past few years have been particularly unkind. The year-end top ten lists for 2011, 2012, and 2013 yield a total of one fade-out.”

On the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new Charles James retrospective: “The Met seems to be telling us—showing us—that we should view [dress and fashion] as high art. This is not a new argument, of course, but in spite of past scholarly and curatorial efforts, it has never decisively taken hold … James would seem the perfect antidote, and in many ways he is: a great designer who was never a celebrity (few outside the field of fashion have ever heard of him), an inveterate craftsman who was also a genuinely imaginative artist—a sculptor of satin and silk willing to sacrifice everything including profits for the perfect seam … ”

September 12, 2014

Staff Picks: A Field in England, A Desert in the Mind

A still from Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England.

Like Nicole, I thrilled to Jed Perl’s essay on Jeff Koons in the current New York Review of Books. I also loved Dan Chiasson’s review of Boyhood in the same issue. In its quiet way this essay amounts to a defense of fiction in the age of social media: “If Boyhood were a documentary, it would involve much more acting, with the subjects self-consciously shaping their on-screen personae (this happens, to an extent, in the Up series). Here, there is nothing to be done: time itself is the real actor.” Both Linklater’s movie and Chiasson’s review reminded me of another experiment with the longue durée—This Is Autism, the 2011 concept album by Anders Danielsen Lie. American filmgoers know Lie as the brooding lead in Reprise and Oslo, August 31, but he is also an accomplished musician and composer. This Is Autism is a song series built on compositions that Lie made as a kid (starting at the age of ten), then revisited as a grown-up; the music seems to have soaked up a childhood’s worth of listening, mainly to parental vinyl in what Lie likes to call the “autistic” tradition, from Steely Dan and Keith Jarrett to Kiss. —Lorin Stein

For me, the description of Ben Wheatley’s most recent film, A Field in England, was instantly appealing: a handful of deserters from the English civil war traipse across a field; ensnared by an alchemist, they are forced to help him hunt for treasure supposedly buried in the field. Oh, and they’re tripping on mushrooms. The film is moody and spare—it’s shot in black-and-white—and the mind-altering effect of the mushrooms adds another textural layer on the progressing horror, making it strange and abysmal. I kept turning to my husband to ask whether he understood what was going on, thinking that I was missing something. He’d recite the plot, as he’d comprehended it, and I realized that I’d managed to grasp exactly what was going on. It’s just that everything seemed, well, kinda trippy. The setting helps to circumscribe the film’s disturbing events, a theater both expansive and enclosed. (It makes sense that Wheatley’s next film is an adaption of J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise.) When one character tells another that he cannot escape the field, he replies, “Then I shall become it!” —Nicole Rudick

Last week I noted the excellent epigraph to Roberto Bolaño’s A Little Lumpen Novelita, but I neglected to say that the novella itself is excellent, too: brisk, nervous, and curiously compassionate, with a conceit I can only describe as Bolaño-esque. A young woman loses her parents and, to make money, visits a blind, withered bodybuilder who likes to slather her in oil before sleeping with her. As usual, Bolaño’s characters endure their miseries with unnerving equanimity; there’s no amount of suffering, we’re led to believe, that can’t be shrugged at. And since this is Bolaño, the book has a surreal, tragicomic dream sequence. (As Jonathan Lethem pointed out in his review of 2666, M.F.A. praxis maintains that dreams make for dull fiction—digressive, freighted with easy symbolism—but Bolaño writes them often and well, with skewed logic and foreboding mental detritus.) The narrator, Bianca, dreams of plodding through the desert with a heavy, white, possibly flightless parrot on her shoulder: “He weighed too much (ten pounds at least, he was a big parrot) to be carried for so long, but the parrot wouldn’t budge, and I could hardly walk, I was shaking, my knees hurt, my legs, my thighs, my stomach, my neck, it was like having cancer, but also like coming—coming endlessly and exhaustingly—or like swallowing my eyes, my own eyes … ” —Dan Piepenbring

Given that Chaucer provides us with the earliest example of the verb “to twitter,” it seems appropriate that his Twitter persona, “Chaucer Doth Tweet,” has now attracted an impressive 29,800 followers. And he’s not the only medieval writer to venture into social media, with the Christian mystic Julian of Norwich, the poet John Lydgate, and the author Sir Thomas Malory all joining him in popularizing #MiddleEnglish. Perhaps the most surprising member of this group, though, is the late fourteenth-century mystic Margery Kempe, who has not one, but four rival Twitter accounts. Best known for dictating The Book of Margery Kempe, Margery spent most of her life repenting for her sins “wyth gret wepyng and many teerys,” being abused by her local community and abstaining from the “abhomynabyl” act of sex with her husband. While it may initially strike us as astonishing that a mystic visionary should have more official Twitter pages than Jay-Z, the online world has more in common with medieval Norfolk than you might think—maybe Margery can no longer be imprisoned by angry priests, but slander and public shaming are still ever present on the web. As @tweetyng_teres puts it: “dey seyn this creatur cryin / dey haytin #wepyn.” Plus ça change, it seems. —Helena Sutcliffe

Self-examination on film is difficult to pull off. Voice-over narration can be trying, and internal debates are difficult to externalize. But Marcelo Gomes’s Once Upon a Time Verônica, now playing at MoMA, walks on this tightrope, thanks in large part to a wonderful performance by Hermila Guedes as the title character. Verônica works as a psychiatric intern at an inner-city hospital in Recife, Brazil, and spends much of her free time taking care of her father. She’s having a crisis, but she can’t really say what it is. The movie’s opaqueness can be frustrating at times; we never learn the details of her father’s illness, for instance, and her love life is treated elliptically. But as the film illustrates, life and art don’t always need to make sense. What I found bold about Verônica is how it never cheats its main character for the sake of advancing a plot. It’s like Veronica tells her father: “We spend our lives wasting it as we choose.” —Justin Alvarez

The Future According to Stanisław Lem

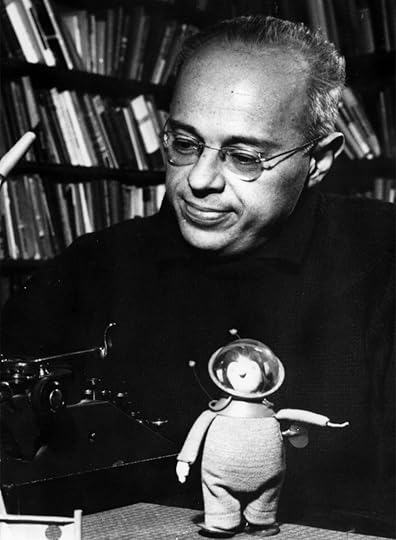

A still from The Congress, a new film adaptation of Lem’s 1971 novella The Futurological Congress.

In his 1971 novella The Futurological Congress, the Polish science-fiction writer Stanisław Lem describes a group of futurologists who have gathered at the Hilton Hotel in Costa Rica to stave off planetary disaster. Overpopulation and resource depletion are at crisis levels; famine and political collapse are just around the corner. Even before the conference begins, events take an ominous turn. Guerrillas kidnap the American consul and start mailing in body parts, demanding the release of political prisoners. As Professor Dringenbaum of Switzerland explains how humanity will soon resort to cannibalism, rioting breaks out in the streets. In response, the Costa Rican government deploys new types of chemical weapons, intended to make the rebels docile and peace-loving. They induce feelings of empathy and euphoria, and come with names like “Felicitine” and “Placidol.” Planes barrage the city with LTN, or “Love Thy Neighbor” bombs.

Among the conference attendees is Ijon Tichy, an unflappable cosmic adventurer with the habit of getting into outlandish scrapes. Having inadvertently received a premature dose of the drugs through the hotel’s tap water, Tichy has the foresight to take refuge from the bliss-inducing crackdown in the building’s sewer system. Nevertheless, he winds up inhaling a near-lethal dose of psychotropic chemicals and tumbles down a dark rabbit hole of hallucinations. When he finally wakes up in the year 2039, after having been cryogenically frozen for decades, he finds a world where such substances have ceased to be used for crowd control and have become, instead, a way of life.

The novella—masterfully translated by Michael Kandel and recently adapted as The Congress, a part-live action, part-animated movie by the Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman—is more a satire than a poker-faced dystopia. Rather than solving its problems, humanity learns to mask them using comically sophisticated pharmaceuticals. In the “psychemized” future, you can take drugs like “gospelcredendium” to have a religious experience, and “equaniminine” to dispel it. Books are no longer read but eaten; they can be bought at the psychedeli, a kind of one-stop psychem superstore. For a friendly conversation there’s “sympathine” and “amicol,” for an unfriendly one “invectine” and “recriminol.” Even acts of violence and revenge are sublimated into ingestible form.

Folman’s movie adopts this premise, but reframes it as a critique of the entertainment industry. Instead of Ijon Tichy, the movie’s main character is the actress Robin Wright, who plays a fictional version of herself. At first, studio executives want to scan her to create a digital avatar that will take over all of her roles. Twenty years and a switch to animation later, they want to produce a drug that will enable anyone to “be” Robin Wright, or at least to believe that they are. The Congress itself is a Hollywood bash celebrating the new age of chemical entertainment, rather than an academic conference on humanity’s doom. As in Lem’s novella, however, this future promises not social and scientific progress, but technological hedonism and senescence.

Lem in 1966. Photo courtesy of his secretary, Wojciech Zemek

Yet Lem was no dystopian, on the whole. Even The Futurological Congress is riddled with good humor, though the world it portrays is bleak. Despite having lived through both the German occupation of Poland during the Second World War and the Communist government that followed it, Lem seldom depicts totalitarian rule. In contrast to George Orwell’s 1984, in which the Party strictly controls the “truth,” Lem preferred to depict societies bogged down by excess information and technology. “Freedom of expression sometimes presents a greater threat to an idea,” he writes in his 1968 novel His Master’s Voice, “because forbidden thoughts may circulate in secret, but what can be done when an important fact is lost in a flood of impostors … ?” This observation rings eerily true today, but Lem wasn’t only trying to critique modern society. He wanted to imagine what the future might actually be like.

This goal animates his kaleidoscopic body of work—a collection so diverse that Philip K. Dick once wrote to the FBI that Lem wasn’t a real person but a committee masterminded by the Communist Party. Lem’s early books include The Hospital of the Transfiguration, a nonscience-fiction novel about a doctor in a psychiatric hospital at the beginning of the Second World War, and The Cyberiad, a series of fable-like tales about two omnipotent “constructors” who don’t foresee the consequences of their creations. In Lem’s most famous book, Solaris, adapted for film by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and again by Steven Soderbergh in 2002, humanity discovers a strange form of extraterrestrial life, but completely fails to understand it. In a sense, Dick was right: given the variety of his subjects and styles, there really is more than one Lem.

He did have certain overarching ideas, however, most of which he laid out in the Summa Technologiae, a magisterial futurological treatise published in 1964. (The book appeared for the first time in English in 2013, in a translation by Joanna Zylinska.) In the Summa Lem doesn’t try to foretell events exactly—such predictions usually project their own time, he writes, like the “ ‘the world full of balloons’ or ‘the total steam world’ of the nineteenth-century utopians and draftsmen.” Rather, he tries to imagine the paths that technology might take, using biological evolution as a blueprint. The two processes aren’t merely analogs, he claims, but different parts of a single evolutionary process. Eventually, technology will take over completely from slow-moving natural selection, resulting in the re-engineering of both our planet and our bodies. What happens after that is anyone’s guess.

Lem, of course, made plenty of guesses, and the idea of “autoevolution”—sometimes referred to as the “singularity”—was an especially favorite subject. Although in the Summa he presents the possibility without moral judgment, in his fiction the results are rarely cheerful. Lem’s 1959 novel Eden, one of his few conventionally dystopic works, features an extraterrestrial civilization that has survived a botched attempt at biological self-intervention. The government responsible now denies its own existence, and its subjects live under a terrifying regime of self-censorship and control. In a more lighthearted story, “The Twenty-First Voyage”—included in the 1957 collection, The Star Diaries—Ijon Tichy visits a planet called Dichotica, whose inhabitants are so advanced that they can make and remake their bodies however they like. At first such technology is used for predictable ends—“ideals in health, congruity, spiritual and physical beauty”—but is soon turned to things like “epidermal jewelry” for women, “side and back beards, cockscomb crests, jaws with double bites, etc.” for men. After a while the Dichoticans abandon humanoid form entirely, leading to attempts at reform and standardization, followed by repression, rebellion, and social breakdown. Unlimited choice, the story argues, can become the greatest burden.

A still from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 adaptation of Solaris.

In his fiction, Lem portrayed not only the fruits of science but also its process and culture. His novels are filled with debates between scholars, struggles between high-minded researchers and government sponsors, and entire histories of fictional scientific fields. In his 1986 novel Fiasco, for example, a group of astronauts argues about life beyond its natural phase. If such beings are so far advanced, their activities should be detectable from space. So where are they? Is their silence the result of our own incomprehension, or are they are invisible for reasons of their own? Perhaps, like the Dichoticans, they are so taken up with perfecting their own organisms that they’ve abandoned space exploration entirely. According to a similar hypothesis, such beings are invisible because technological ease has resulted in a “Second Stone Age” of “universal illiteracy and idleness.” When everyone’s needs are perfectly met, it “would be hard, indeed, to find one individual who would choose as his life’s work the signaling, on a cosmic scale, of how he was getting along.” Rather than constructing Dyson Spheres, Lem suggests, advanced civilizations are more likely to spend their time getting high.

Yet Lem also believed that such a future isn’t inevitable. Technological progress could result in an irreversible inward turn, but it could also lead to contact with other life forms. Nineteen sixty-one’s Return from the Stars presents humanity at just such a crossroads. An astronaut named Hal Bregg returns to Earth after a ten-year voyage. Because of relativity, 127 years have passed on Earth, which has become a seeming utopia. Scientists have invented a surgical procedure called “betrization,” which instills a repulsion to violence and thus causes an end to war and crime. Yet with this new peacefulness comes an aversion to high-risk endeavors, including the kind of voyage from which Bregg has recently returned. According to a new line of thought, space expeditions are actually futile, not only because of their danger but because relativity makes them “purveyors of dead information.” By the time the astronauts return to Earth the society that sent them is gone, and whatever world they discovered will have changed as well. Yet there are those who disagree: “And of what use was Amundsen’s expedition? Or Andree’s?” one characters asks. “The only clear benefit lay in the fact that they had proved a possibility.” Like George Mallory said of Everest, the reason to climb it is “because it’s there.”

Lem, who died in 2006, couldn’t have lived long enough to test most of his predictions, and neither will we. But in his writing he attempted one of the most ambitious feats the human imagination can undertake: he tried to picture, by turns seriously and playfully, not just how humanity might appear fifty or a hundred years down the line, but a thousand, ten thousand, or more. Predicting the future is an old game, and not usually a noble one. Prophets turn out to be wrong, or self-interested, or both. Lem may also have been wrong, as he well knew. But for him, predicting the future was a way to think about the world on the largest possible scale—an effort to transcend our bodies and brains through logic and imagination. Nobody can really know the future. But few could imagine it better than Lem.

Ezra Glinter is the deputy arts editor of the Forward. Follow him on Twitter.

Songs of Innocence

Giulio del Torre, Zwei raufende Buben, 1927.

If you live in my building on the Upper West Side, you do not need to own an alarm clock, at least not if you want to wake up at eight A.M. Sleeping beyond that hour is impossible—that’s when the preschool opens its yard for the first playtime of the day.

It is a very lovely way to wake up, if you’re in the right frame of mind. Joyful shrieking, terrified screaming, feuds and rivalries and friendships all at once, magnified by the walls all around them. It is much better to take a Blakean view of it, especially if you work from home, because there are periodic recesses throughout the day, and their collective energy is unflagging.

I always liked the background noise of the playground; working by myself all day, it made me feel less alone. It didn’t really strike me as strange until I conducted an interview in my apartment and, when I tried to transcribe it, realized the voices were obscured by the wall of child-call in the background. Still, I didn’t mind; I threw my windows open and welcomed it, as some people do the constant buzz of public radio.

Then, recently, a second preschool opened. This one faces the other window, and in fact it may be a daycare, because the children are younger, and there are babies, too, and they cry, and sometimes a particularly harried teacher raises her voice in what sounds like near-hysteria. Once again, the walls of the surrounding buildings amplify the noise. The sounds now come from all sides, at all times. It is often just crying, or shrieking, but other times a word comes through; “ACTION” and “DIE!” were the most recent. At one of the schools, the teachers summon the children with an intricate series of loud clapping patterns that I now hear in my dreams. It cannot be denied: I am going mad.

Of course, the solitude of working from home can already lead one to “go strange.” “Going strange” is the prelude, in my family, to “garden-variety madness,” which is how we refer to any obvious craziness that goes undiagnosed, which is to say all obvious craziness. The first sign is a need to talk, furiously, to any stranger, until you see their eyes widen with fear and apprehension. This usually occurs after two days of total solitude. On the third day, you become furtive and sly; you peer out of your peephole to make sure you won’t encounter fellow human beings and take elaborate backstairs routes to the mailboxes to avoid any interaction. By the fourth day, you have ceased to collect your mail.

In these moments, I begin to worry that, in fact, the chorus of children is in my head. But then I look out my window, and there they are—I don’t do this often, as it makes me feel distinctly like Henry Darger—and there is the one little boy who chases all the other four-year-olds around and tries to kiss them and screams “I LOVE YOU!” seemingly without discrimination. The other kids seem scared of him, but I think they love it all, too.

Win Two Free Front-Row Seats: Ben Lerner in Conversation with Paul Holdengräber

The Paris Review has recently published two stories by Ben Lerner, who won our Terry Southern Prize this year: first was “False Spring” (issue 205) and then “Specimen Days” (issue 208). Both are excerpts from his excellent new novel 10:04. If you’ve opened a newspaper or book review in the past month, you’ve likely encountered rhapsodic praise for 10:04. The Wall Street Journal wrote, “Mr. Lerner packs so much brilliance and humor into each episode … this brain-tickling book imbues real experiences with a feeling of artistic possibility, leaving the observable world ‘a little changed, a little charged.’” In The Times, Dwight Garner wrote that Lerner is “among the most interesting young American novelists at present,” and in Bookforum, Christian Lorentzen called 10:04 “a beautiful and original novel … it signals a new direction in American fiction.” NPR said that it’s “strange and spectacular … Don’t even worry about classifying it; just let Lerner’s language sweep you off your feet.”

And why not let that sweeping happen in person? Next Tuesday, September 16, Lerner will appear at the New York Public Library in conversation with Paul Holdengräber—it’s sure to be an expansive interview, and we’re giving away two front-row seats. (For proof of Holdengräber’s conversational acumen, check out his Art of Nonfiction interview with Adam Phillips, which we published in our Spring issue.)

For a chance to win, retweet our announcement below before three P.M. EST today. We’ll select two winners at random. Bonne chance!

We have two free front-row tickets to Tuesday’s @LIVEfromtheNYPL event with Ben Lerner. Retweet by three P.M. EST today for a chance to win!

— The Paris Review (@parisreview) September 12, 2014

Hidden Mother, and Other News

Spot the mom. “Photographer Laura Larson’s series, Hidden Mother, presents a survey of nineteenth-century tintype portraits in which the mother of the child was included in the photograph, but obscured.” Image via the New Republic

“All American fiction is young-adult fiction … to be an American adult has always been to be a symbolic figure in someone else’s coming-of-age story. And that’s no way to live. It is a kind of moral death in a culture that claims youthful self-invention as the greatest value. We can now avoid this fate. The elevation of every individual’s inarguable likes and dislikes over formal critical discourse, the unassailable ascendancy of the fan, has made children of us all. We have our favorite toys, books, movies, video games, songs, and we are as apt to turn to them for comfort as for challenge or enlightenment.”

Alan Moore, the author of Watchmen and V for Vendetta, has written a million-word novel. “To put that ‘more-than-a-million-word document’ into context: Samuel Richardson’s doorstopper, Clarissa, runs to around 970,000 words, 200,000 more than the Bible. War and Peace is around 560,000 words long.”

The latest chapter in the reinvention of the lending library: lending helpful objects alongside books, e.g., a pole and tackle, knitting needles, cake pans, GoPros, telescopes.

The tintype portraits of the nineteenth century needed long exposures, which meant that any family trying to get baby pictures had to have extremely patient children. How to get the kids to sit still? Include their mother in the shot—but obscure her, because these are baby pictures, after all. “In some instances, the mother would hold her child, with a cloth or props hiding her from the lens. Or, she would be painted over by the photographer after the image had been taken. In other examples, the mother is entirely absent from the frame, save for an arm, holding the child in place. The results are both funny and slightly disturbing.”

Herman Wouk’s Don’t Stop the Carnival is touted as “the best novel ever set in the Virgin Islands.” A new novel by Tiphanie Yanique aims to set its record straight: “Virgin Islanders don’t really give [Don’t Stop the Carnival] much thought. We don’t think it’s a good representation of who we are. And yet this was the book being marketed as a credible anthropological text … The Virgin Islanders in the book are buffoons … I wanted to write something that people would say, ‘If you’re going to read the Herman Wouk, you have to also read the Yanique.’”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers