The Paris Review's Blog, page 664

September 11, 2014

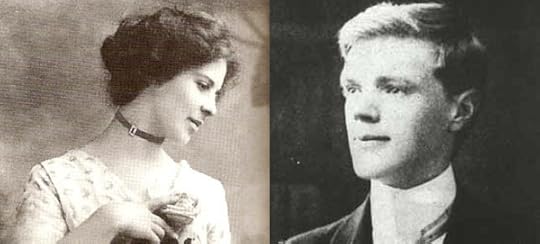

Writing Advice from D. H. Lawrence at Twenty-One

On September 11, 1906, D. H. Lawrence turned twenty-one. Around that time he wrote this letter to Louie Burrows, a friend with whom he attended University College in Nottingham. The letter dissects one of Louie’s essays about art; it finds Lawrence full of youthful arrogance (“Like most girl writers you are wordy”) and optimism (“the world abounds with new similes and metaphors”). Lawrence and Burroughs corresponded steadily for years; in 1910, they were engaged, though Lawrence broke off the engagement in 1912. (The “J” he refers to here is Jessie Chambers, another of his love interests.)

Dear Louie,

I am going to quizz [sic] your essay, not in the approven [sic] school-mistress style, but according to my own whimsical idea, which you may or may not accept. First of all I will find fault.

I do not like the introductory paragraph, it is like an extract from a Catalogue of Pictures for sale at some auctioneers … Like most girl writers you are wordy. I have read nearly all your letters to J, so I do not judge only from this composition. Again and again you put in interesting adjectives and little phrases which make the whole piece loose, and sap its vigour. Do be careful of your adjectives—do try and be terse, there is so much more force in a rapid style that will not be hampered by superfluous details. Just look at your piece and see how many three lined sentences could be comfortably expressed in one line.

I know my essay was squeezed down almost to incoherence because I did not want it to be too long. I am very glad you saw how I had compressed; if I had filled in and merged off my thoughts Miss B[ecket] would not have accused me so strongly of confusion.

Again, don’t use hackneyed adjectives. “Shapely heads—fallen heroes—white bear on aged breast” you know these are in everybody’s mouth. If you would write, try to be terse and in some measure original—the world abounds with new similes and metaphors …

Things which are obvious are worth no more than a mention. If you cannot tell people of something they have not seen, or have not thought, it is hardly worthwhile to write at all. Try and study people, and the living soul which is the essence of mankind. If you have externals, they must represent something. I write to you as a would-be aspirant after literature, for I know you are such.

I like above all things your enthusiasm, and your delightful fresh, youthful feeling. Don’t be didactic; try and make things reveal their mysteries to you, then tell them over simply and swiftly, without exaggerating as I do. I think you will do well. You are brighter than Jessie, more readable, but you are not so powerful. You will doubtless succeed far better than I who am so willful. Be your own bright ingenuous self, and you are sure to make a delightful impression.

I am going to make my next try now. Let me see what you do—I am all interest.

Story Time

From the cover of a “Fun with Music” disc.

Ann Rachlin, storyteller, MBE, and pioneer of music appreciation, has been working for years—she’s now eighty—but she really came to prominence in the mideighties, when she started teaching little Prince William. I wonder if that’s when my mom bought her records. Whatever the reason, her “Fun with Music” series was in heavy rotation at our house, and the distinctive, lilting rhythms of her idiosyncratic narratives was the sound track of our childhoods. I think if you’d asked me between the ages of four and six which celebrity I would have most liked to meet, the answer would have been Ann Rachlin. (Well, Ann Rachlin and Jeff the mannequin from Today’s Special.)

The records (and later tapes, for playing in the car) featured narration over classical music pieces. Sometimes, as in the case of Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kijé, or the deeply distressing Swan Lake, Rachlin based her tale on a preexisting story. Others were wholly original, and often unabashedly bizarre. (I am thinking especially of Lost Coin in a Fountain, set to Respighi.) To call Rachlin’s style “expressive” is a vast understatement: her voice rises and falls dramatically, she takes on all characters with gusto, she evokes laughter and tears and bafflement. She is so wholly uninhibited that it’s shocking even to a child. Maybe especially to a child. And while her tales are all designed to capture a child’s imagination, she does not shy away from sadness and even, occasionally, tragedy. (See: Swan Lake.)

The recordings are all still available, and many can be found on Spotify, too. Along with The Carnival of the Animals (with doggerel by Ogden Nash), Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic’s Peter and the Wolf, I think they remain some of the very best classical-appreciation recordings for children. (If, indeed, this is its own category.) I have gifted them with success, and having recently relistened to a few highlights, I can say with authority that they’re just as eccentric as I remembered.

You can get a sense of this from the following clip. Frankly, her outfit alone—a sort of contra-dancing princess gown—tells quite a story all on its own.

Buzzing in My Ears

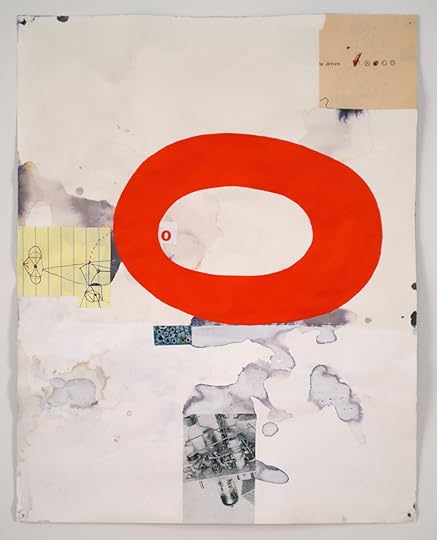

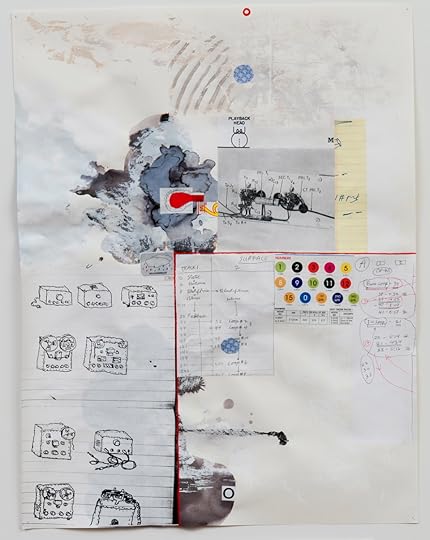

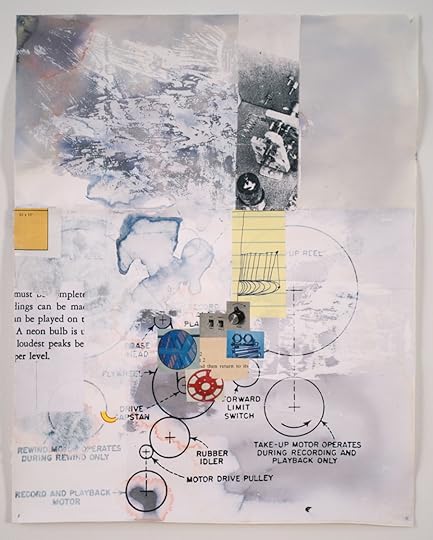

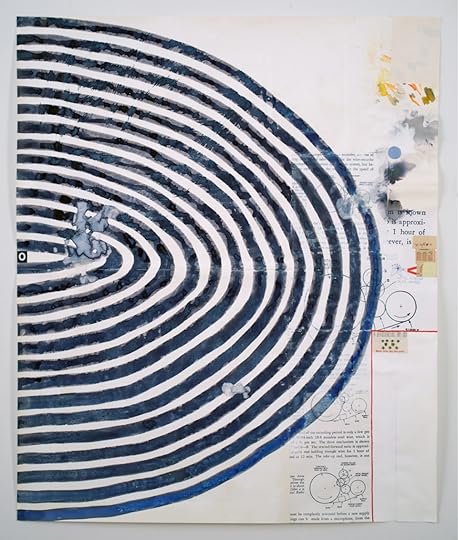

Steve Greene, Buzzing in My Ears, 2013; ink, acrylic, collage, gesso on paper; 14 x 11"

A few months ago, I wrote about my persistent fascination with industrial-supply catalogs, especially the Grainger catalog, which runs to many thousands of tissue-thin pages and contains everything from centrifugal belt-drive downblast exhaust ventilators to cementitious mortars.

A number of readers wrote to say they share my interest in these catalogs, which feature dauntingly precise language and serve as a kind of paean to utility. Among those who came out of the woodwork was the artist Steve Greene, who’s married to The Paris Review’s finance manager, Janet Gillespie. Steve has been using supply catalogs in his drawings and collages for years, to incredible effect; he was kind enough to send me some of his work, and to elaborate on his sources:

My go-to resource for years has been the Uline Shipping Supply Specialists catalog, which I subscribe to so I can keep replenishing favorite images. Nice heavy magazine paper with great color. An old favorite is the Arco Officer Candidate Tests by Solomon Wiener, Colonel, AUS-Ret, which is full of useful tips for aspiring military officers and practice tests that have been partially filled out in red ink. The others I take myself—the more wrong answers, the better. Then there are the Mobile Manual for Radio Amateurs, from 1960, and Magnetic Recording by S. J. Begun, from 1949, neither of which I would dare cut up—but both spend a lot of time on the copy machine. I still have stacks of pages from the Global Equipment Co. catalog, which I’ve been using for about thirty years.

I particularly enjoy the random poetry of these books and catalogs, and their listings and names often make their way into my titles:

Accelerator Pump Cam

Tough, Tear Resistant, Out-of order

Two Tubes

Below are three additional pieces by Steve; you can see more of his work here.

Radio Waves, 2012; ink, collage, gesso on paper; 24 x 18"

A Neon Bulb, 2013; ink, collage, gesso on paper; 14 x 11"

Approximately 1 Hour of Ever, 2012; Ink, collage, gesso on paper; 36 x 30"

Finding the Question That Hasn’t Been Asked: An Interview with Lynne Tillman

Lynne Tillman, Second Avenue, New York City, 2013. Photograph: Mark Alice Durant.

Writing a short introduction about Lynne Tillman isn’t easy; her singular and visionary writing covers a great deal of territory. The author of twelve books, she is adept at fiction, short and long essays, cultural critique, and interviews. A sampling of just three of her books conveys the scope of her work: her novel American Genius: A Comedy follows the obsessive inner monologue of a single character for almost three hundred pages; This Is Not It is a compendium of twenty years of witty and risky novellas and short stories, some as short as a paragraph; and Bookstore: The Life and Times of Jeannette Watson and Books & Co. weaves together the voices of Susan Sontag, Fran Lebowitz, Paul Auster, Calvin Trillin, and many others to tell not just the story of the rise and fall of the iconic, well-loved Books & Co. but that of the changing landscape of publishing.

Her new book, What Would Lynne Tillman Do?, is a collection of recent essays—on Andy Warhol’s a: A Novel, on the lives and work of Paul and Jane Bowles, and on Edith Wharton and architecture, to name just a few—and interviews with Harry Mathews, Paula Fox, Lebanese-American writer and visual artist Etel Adnan, and German painter Peter Dreher. Each piece, whether essay or interview, is illuminated by Tillman’s wit, intellect, and curiosity. When the book was released earlier this year, Jason Diamond of Flavorwire declared 2014 to be “the year of Lynne Tillman.”

I spoke with Lynne Tillman at the New School, as part of the university’s Summer Writers Colony. Fiction and nonfiction students had spent three days reading What Would Lynne Tillman Do? and the questions I posed reflected their curiosity, as well as my own, regarding the processes and practices that allow her to transition easily between genres. Tillman was eager to answer, and the qualities that characterize her writing shone through in her answers.

In your 2009 essay, “Doing Laps Without a Pool,” you write, “I don’t want to take a position. Not taking a position is a position that acknowledges the inability to know with absolute surety, that says: Writing is like life, there are many ways of doing it, survival depends on flexibility. Anything can be on the page. What isn’t there now?” All those interesting negatives—“not taking a position,” “the inability to know,” “what isn’t there now”—reminded me of Keats’s famous letter in which he used the term negative capability. When you begin to build an essay, do you feel as if you’re exploring what you don’t know, precisely because you don’t know? Or do you begin with a firm idea or a mystery that you want to explore more deeply?

I begin nonfiction essays in a similar way to fiction. I have some questions in my mind, things that I’m interested in writing about, and in fiction I find a voice through which to do that. On the other hand, in an essay, I assay some of what I think I know, and then, as I go along, I realize that I don’t know what I thought I knew. I wrote “Doing Laps Without a Pool” because Rebecca Woolf was editing an anthology of work from Fence, with commentaries by former and current editors—I had been the fiction editor for fifteen issues. She was looking for essays that would somehow relate to our experience of the magazine. The reason Fence has its title is that they didn’t want to take an absolute position about what kind of writing they represented, and that appealed very much to me. I’ve been criticized for that, too—for being so involved and engaged with narrative. As if narrative were a simple thing. It was a hard essay to write because I wanted to address all those writers with whom I’d had arguments about stories but had never found the words to respond adequately. There are no answers in “Doing Laps Without a Pool,” but I’m saying that terms like experimental or traditional or mainstream or conventional are not resonant. They’re not helpful to writers or to ways of thinking about writing. At least they’re not helpful to me.

When I write, I try to find my way through it. Whether it’s an essay or a story, I don’t really know where I’m going. For example, in the essay “Point of View,” I asked myself, Why is it that people have been so harsh about Diane Arbus over the years? But I didn’t want to think about it in the ways it had been thought about. Half the battle is asking a different question, finding the question that hasn’t been asked. So in the case of Diane Arbus, I began to think about why it is that she’s considered so explosive by some, and somewhat exploitative. I came up with this notion of a “benign-looking contract”—that perhaps we had somehow thought we could look at documentary photography without feeling complicit or voyeuristic. I asked myself a question that hasn’t been answered or addressed yet. That’s one way I approach writing—going out on a limb with what is unsaid. In an essay, you have to take a position, finally, but you can also take many positions, and you can qualify those positions as well.

You do that in your essay about the Rolling Stones. The piece starts out being about getting dressed in the morning, then it moves into hunger, and then the Stones’ first concert in New York. And you have a great line about how “no one clapped or shouted, everyone was fed up, pissed off, let down.” Yet what you finally came away with was, “Life continued but something had changed: the Rolling Stones had played New York.”

I contributed that to an anthology called The Show I’ll Never Forget: 50 Writers Relive Their Most Memorable Concertgoing Experience. I had several shows in mind, but I didn’t know anyone else who’d been to that show, except for the friend with whom I’d attended the concert, while I was still in college. She was older. I thought I’d write about that because it remained so vivid. But I started it in that way to set up the kind of person I saw myself as then—a person who would like the Rolling Stones much better than the Beatles. You know, a depressed, angry person.

By the end, you come away with a sense of resolution—it wasn’t important how it unfolded, simply that the Stones had been here.

I don’t know if it was so much a resolution. It was more like, here’s this character—and to me she’s a character—who starts out saying, Every day is the same. She just gets out of bed every day, but then something was different—the Rolling Stones had played New York.

Your essays on Paul and Jane Bowles seem to turn on an idea of Paul Bowles having been “forever amused by something invisible buzzing around him, and that something kept him going. Maybe he was amused just to be alive.” But I wouldn’t say his stories and novels are about amusement.

They’re very dark.

Is that what first drew you to his work—those kinds of unflinching explorations of overwhelming underworlds?

What first drew me to his work was that he was an American abroad, and I was fascinated with that. I was living in Amsterdam, and everyone was talking about him and his work. After college, I had wanted to get out of America and lead what I thought was a writer’s life. Paul and Jane Bowles were models. Gertrude Stein was a model. There was the idea that in order to write you had to leave home, and maybe become an expatriate or even an exile. And that was something I very much admired in him. And also that darkness in his writing, the strangeness.

But people who write about dark things are not necessarily dark themselves. Bowles had a great sense of humor. Some of his autobiography, Without Stopping, is really hilarious. So is his nonfiction book, Their Heads Are Green and Their Hands Are Blue. He started out, in the thirties, as a composer, and he was sent by the Library of Congress to record Moroccan music—those recordings are still in the Library of Congress—and the book is about that trip. Absolutely wonderful essays about his travels in Morocco to record music that had never been recorded before. And that’s, of course, a connection to the Rolling Stones, and what they heard and became interested in—Joujouka music.

You begin “Nothing Is Lost or Found,” on the Bowleses, with a beautiful quote from Buber—“I once read ‘All journeys have destinations of which the traveler is unaware.’ The beginnings of journeys and narratives can be as surprising as their secret destinations.” The part about destinations is certainly true of some of the characters in Bowles’s stories and, less harrowingly of course, in your own essays. Is there some secret narrative destination that you’d still like to arrive at, that you haven’t yet?

There’s a wonderful essay by Mary McCarthy called “Settling the Colonel’s Hash.” Mary McCarthy was such a brilliant writer, and her nonfiction is nonpareil. In that essay she said something like, if there are no surprises for the writer, they’ll be no surprises for the reader. I really think that’s true. As you write, you’re finding things out. Now that’s a very hard thing to do, writing that way. Writing in any way is hard to do. But if you don’t really know where you’re going and you’re trying to figure it out as you go along, it’s not pleasant. It’s not as though you wake up and say, Hey, let’s go on a journey today. Let’s find something. I’m not that optimistic. I wish I were. But you’re trying to figure out something, and that’s why, going back to your very first question, I don’t want to be proscriptive, because maybe there’s a way for me to get somewhere that would be considered by some to be, you know, Oh, that’s not the way people do it anymore. But maybe, in the moment of writing, that could very well be the way to do it.

You wrote the introduction to Charles Henri Ford’s diary, Water From a Bucket, and you were his date for the Paul Bowles concert at Lincoln Center in 1995. But did you ever interview him?

I knew him a long time, and in some ways having any conversation with him was interviewing him. At one point he said to me, You’re so good at interviewing, you’re so good at asking me questions, why don’t you write my autobiography? Or I could write it with you. And we’ll do it by taping. I said, Okay, but who pays for the transcriber? And he said, You do! So the book never happened, because it was the mideighties, and I was making so little money, and there he was living in the Dakota, with a house he owned in Paris. It was crazy. He was fascinating and fun, but he was very cheap. It was astounding, in fact. He was late once to his own book party. It was snowing, and when he finally arrived, an hour late, he said that the bus had broken down and he had to wait for another bus. He wouldn’t take a taxi to his own book party.

And yet, reading his diary, his life was so fabulous—hanging out with the Sitwells, Cocteau, Leonora Carrington, Gala and Salvador Dalí …

I read his diary for the first time in the late seventies, and said to him, Oh, this is great, you should publish this. He sort of ignored me, but then I was a kid, really, unpublished—no one important to him in that way. I read it again in the late eighties, and I said again, You really should publish this. He said he just wasn’t interested. Then in the midnineties—and by then he was probably in his mid- to late eighties—I realized it was sort of now or never. I’d always thought the diary was an incredible document, unique in the way that he’d written it and in the way that it gave a sense of that period, of a certain life lived during that period, a life that would otherwise not be known. But he said, I’m too involved in what I’m doing now, and besides I don’t live in the past. He was pretty incredible that way—eighty-six and “I don’t live in the past.” Finally I said that I was going to get it published for him.

It’s a longer, sorrier story, but I got in touch with a publisher who said he’d publish it, and then four years later nothing had happened. Even though, when I’d sent it to him, I’d said, Charles is eighty-six, and I want this to come out before he dies. There was also very much a feeling in me that you don’t want to be forgotten when you’re an older person. You want a younger writer to come along and say, Your work is still valid and I’m going to get it published. So, on October 1, 2000, I went to his apartment in the Dakota, and saw that he was not doing well, and thought to myself, I said I was going to get this published, I made a commitment to him, and also to myself. So, determined to do it, I called the delinquent publisher the next day and wheedled it out of him that he wasn’t going to do it. He mailed the manuscript back to me, and, luckily, it arrived, because it turned out to be the only extant copy. It wasn’t even the original. I didn’t know where the original was, and Charles didn’t, either. Then I immediately got in touch with Jonathan Rabinowitz of Turtle Point Press, because I thought he’d love this book. Jon told me he was going to a bar mitzvah on Saturday morning in the West Village—not far from where I live—and if I could get it to him he’d read it over the weekend and let me know Monday morning. I did, and he called me that Monday and said, Let’s do it. We had it out in eight months. And Charles lived another six or eight months after that, so he saw the book. The book party Jon planned had to be cancelled—it had been set for September 13, 2001. Charles never had a party, but he had the book.

I was so entranced by his diary that it distracted me from my preparations for my talk with you! His sensibility was so completely of a different time, and I felt that by reading this intimate document I was living that time through him.

I think what I love most about diaries is the presentation of a sensibility. Sensibilities actually shift in different times, and with a diary you can discern the sensibility of an individual who is an individual but also a product of his or her time and society. A diary represents that. It’s a recording in the moment. Diaries are about private thoughts, secret feelings. It seems people don’t believe in having secrets anymore. And that’s a whole other idea then, and what does that mean? I think we’re just beginning to deal with what that means.

In “The Last Words Are Andy Warhol,” your final lines are “How do we know what to pay attention to. How do we know for ourselves what’s important. How do we choose. How do we know if it’s art. How do we decide what to see and to read. How can we tell unless everything is there to see and read.” These aren’t posed as a series of questions, but as statements. You’re not asking. You’re saying that this is what’s going on. I think it’s difficult now for writers to maintain an individual vision with so much encroaching from all sides.

I might have an issue with the idea of an individual vision, because, for me, being a person is so shot through with everything else that I’m not really sure we’re in control of what constitutes our individual vision, certainly not entirely. The question that you’re asking, though, is something we all wrestle with. How do I know what I think? How do I figure out what it is that I’m thinking about? I know that thinking about thinking is what an essay helps me to do. I recently learned that Einstein would go into a room and would sit for something like three days—I mean, I guess he would eat something every once in a while—but he would just sit and think, and that’s what his activity was. The activity of thinking, without necessarily doing, or without committing it to something, is an ideal that we could be doing more. We might think more, take time, rather than need everything to be instantaneous.

But in our own lives, how do we get ourselves to think about how we think and why we think it? And then, of course, that’s the place essays come from. And where all writing comes from.

Sharon Mesmer is a poet and fiction writer. She is the author, most recently, of the poetry collections Annoying Diabetic Bitch and The Virgin Formica and the fiction collection Ma Vie à Yonago: Illuminations. She teaches at NYU and the New School.

The Kids Are All Right, and Other News

New research suggests that this American youth and those like him have not entirely gone to seed.

Young Americans at the library: do they even, like, get it, what with all their young-person gizmos and e-gadgets? They do, kind of. Among the findings of a new Pew survey: “Despite their embrace of technology, 62% of Americans under age thirty agree there is ‘a lot of useful, important information that is not available on the Internet,’ compared with 53% of older Americans who believe that … 88% of Americans under thirty read a book in the past year, compared with 79% of those ages thirty and older.” But: “36% of Millennials say they know little or nothing about the local library’s services, compared with 29% of those thirty and older.”

Not unrelatedly: “In 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, America’s book publishers took an audacious gamble … over the next four years, publishers gave away 122,951,031 copies of their most valuable titles … By giving away the best it had to offer, the publishing industry created a vastly larger market for its wares. More importantly, it also democratized the pleasures of reading, making literature, poetry, and history available to all.”

Fact: Tolstoy was, in 1910, captured on film. (Alas, by the time the talkie was invented, he was no longer among the living.)

The history of “Can This Marriage Be Saved?”, the once-thriving advice column from Ladies’ Home Journal: “For a modern reader of the column’s 1950s and sixties archives, it’s hard not to be horrified by the complete and utter awfulness of many of the husbands … more shocking still are the counselor’s responses. No matter how bad it got, the counselor always managed to find a way to blame the woman for the couple’s problems.”

Before the Man Booker Prize shortlist, with only two of its six authors hailing from the U.S., was announced, defeatist British novelists feared the list would be overrun with Americans. “Why did they assume their American counterparts were better? Or if they thought Americans were just different, why did they assume judges would prefer the game the Americans were playing? Saul Bellow is dead. John Updike is dead. David Foster Wallace is dead, and Philip Roth has made announcing his retirement a full-time job.”

September 10, 2014

Borderline

Though she’s known mainly for her poetry, H. D. was a cineaste, too, in both senses of the word—in the late twenties she formed the Pool Group with Kenneth Macpherson and Bryher (the pen name of Annie Winifred Ellerman). They published a film journal, Close Up, to which H. D. frequently contributed, and they made a number of films, only one of which survives in full. It’s 1930’s Borderline, starring Paul Robeson opposite H. D. herself, credited here as Helga Doorn. It’s about an interracial, bisexual love affair—not so much a love triangle as a love quadrilateral—and, yes, it’s available in toto on YouTube. As the Criterion Collection says, the film “boldly blends Eisensteinian montage and domestic melodrama.”

The Solar Anus

Photo: Steve Kollis, via Flickr

Happy birthday to Georges Bataille, connoisseur of Eros, born on September 10, 1897, a simpler time he took it upon himself to complicate. Actually, to call him an erotic connoisseur grossly understates what so many readers find, uh, gross about him. Suffice it to say his work revels in varieties of sexual expression that remain taboo today; a given Bataille text presents you with a veritable cavalcade of the debauched and the proscribed, and, worse still, makes all of it seem terribly worth investigating. Even his fellow Continental philosophers—not exactly vanilla adherents of the missionary position—thought he was something of a degenerate. Jean-Paul Sartre said Bataille “incarnated human sexuality in its most degraded form”; André Breton described him more succinctly as a “sick and dangerous pervert.”

But history teaches us that perverts make fine litterateurs, and Bataille is no exception. (Not to say there aren’t exceptions. There are plenty.) In Paris, he worked as a librarian and at night went drinking and whoring on the rue Pigalle. His first novel, 1928’s L’Histoire de l’oeil—Story of the Eye, which he published under the pseudonym Lord Auch, or aux chiottes, or “to the shithouse”—was hailed not as a transgressive surrealist masterwork but as pornography, plain and simple. Its reputation has improved since then: it’s still regarded as porn, just the good kind. (John Wray wrote about it for the Daily a few years ago.)

Here, for your edification and titillation, is a bit from The Solar Anus, a short something-or-other published in 1931. I don’t know what you’d call it. It’s metaphysics. It’s a taunt. It’s a series of aphorisms. It’s an extended metaphor that stops shy of allegory. It’s a hymn; it’s a rant. And what it lacks in logical validity it makes up for in images. Among the lines of inquiry pursued: the passage of energy, heliophilia, heliophobia, fecundity, decay, volcanoes, the phallic, the Sapphic, the erect, the supine, excretion, intake, and many other things besides. Have at it:

When I scream I AM THE SUN an integral erection results, because the verb to be is the vehicle of amorous frenzy …

The two primary motions are rotation and sexual movement, whose combination is expressed by the locomotive’s wheels and pistons.

These two motions are reciprocally transformed, the one into the other.

Thus one notes that the earth, by turning, makes animals and men have coitus, and (because the result is as much the cause as that which provokes it) that animals and men make the earth turn by having coitus …

An abandoned shoe, a rotten tooth, a snub nose, the cook spitting in the soup of his masters are to love what a battle flag is to nationality.

An umbrella, a sexagenarian, a seminarian, the smell of rotten eggs, the hollow eyes of judges are the roots that nourish love.

A dog devouring the stomach of a goose, a drunken vomiting woman, a slobbering accountant, a jar of mustard represent the confusion that serves as the vehicle of love.

A man gets up as brusquely as a specter in a coffin and falls in the same way.

He gets up a few hours later and then he falls again, and the same thing happens every day; this great coitus with the celestial atmosphere is regulated by the terrestrial rotation around the sun.

Thus even though terrestrial life moves to the rhythm of this rotation, the image of this movement is not turning earth, but the male shaft penetrating the female and almost entirely emerging, in order to reenter …

Beings only die to be born, in the manner of phalluses that leave bodies in order to enter them.

Plants rise in the direction of the sun and then collapse in the direction of the ground.

Trees bristle the ground with a vast quantity of flowered shafts raised up to the sun …

But the first form of solar love is a cloud raised up over the liquid element. The erotic cloud sometimes becomes a storm and falls back to earth in the form of rain, while lightning staves in the layers of the atmosphere.

The rain is soon raised up again in the form of an immobile plant.

Animal life comes entirely from the movement of the seas and, inside bodies, life continues to come from salt water.

The sea, then, has played the role of the female organ that liquefies under the excitation of the penis.

The sea continuously jerks off.

Solid elements, contained and brewed in water animated by erotic movement, shoot out in the form of flying fish.

The erection and the sun scandalize, in the same way as the cadaver and the darkness of cellars.

Vegetation is uniformly directed towards the sun; human beings, on the other hand, even though phalloid like trees, in opposition to other animals, necessarily avert their eyes.

Human eyes tolerate neither sun, coitus, cadavers, nor obscurity, but with different reactions …

The terrestrial globe is covered with volcanoes, which serve as its anus.

Although this globe eats nothing, it often violently ejects the contents of its entrails.

Those contents shoot out with a racket and fall back, streaming down the sides of the Jesuve, spreading death and terror everywhere.

In fact, the erotic movements of the ground are not fertile like those of the water, but they are far more rapid.

The earth sometimes jerks off in a frenzy, and everything collapses on its surface …

The Sun exclusively loves the Night and directs its luminous violence, its ignoble shaft, toward the earth, but finds itself incapable of reaching the gaze or the night, even though the nocturnal terrestrial expanses head continuously toward the indecency of the solar ray.

The solar annulus is the intact anus of her body at eighteen years to which nothing sufficiently blinding can be compared except the sun, even though the anus is night.

Read the whole thing here, courtesy of the Anarchist Library.

Robert Lowell’s “Epilogue”

Photo: Elsa Dorfman

If you write, and you are not a journalist, and you don’t write fiction, people want to know why. These are hard questions to answer. Sometimes one admires fiction too much to attempt it. Sometimes one lacks the gift for invention. No one gets at the particular challenges of the fact/fiction relationship—or indeed, the exigencies of the creative process—better than Robert Lowell. Especially the poem “Epilogue.” Lowell’s work may be a monument to unapologetic narcissism (an artistically necessary narcissism, defenders could say, or at the very least indivisible from either his genius or his illness) but here, it seems to me, there is only enough self to propel the project at hand. If you listen to him read it, he sounds downright humbled by the weight of creative challenge. As a friend pointed out, it is interesting that his stepdaughter should title her memoir—so full of his destructive recklessness—Why Not Say What Happened? After all, this poem is more introspective, less destructive, than so many others. That is for her to say, of course. In a way, it’s the best memoir title in the world.

Those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme—

why are they no help to me now

I want to make

something imagined, not recalled?

I hear the noise of my own voice:

The painter’s vision is not a lens,

it trembles to caress the light.

But sometimes everything I write

with the threadbare art of my eye

seems a snapshot,

lurid, rapid, garish, grouped,

heightened from life,

yet paralyzed by fact.

All’s misalliance.

Yet why not say what happened?

Pray for the grace of accuracy

Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination

stealing like the tide across a map

to his girl solid with yearning.

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.

To Learn Something

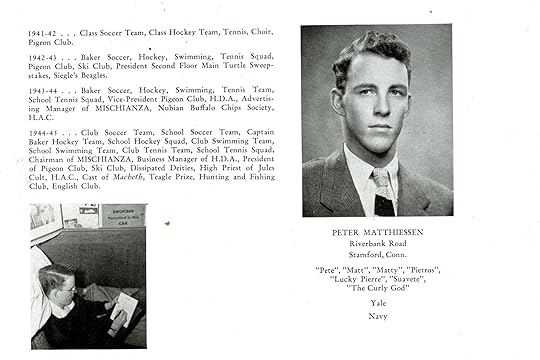

This remembrance of our founding editor, Peter Matthiessen, originally appeared in the Summer 2014 issue of Hotchkiss Magazine ; we’re grateful to the staff and to Lewis Lapham for allowing us to publish it.

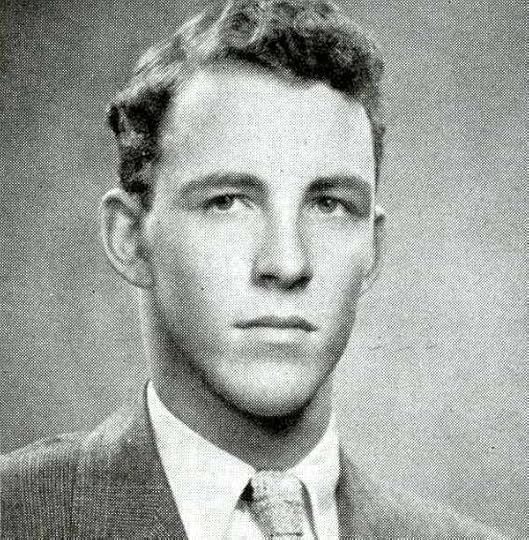

Peter Matthiessen in the 1945 Misch, the Hotchkiss School’s yearbook.

I first encountered Peter Matthiessen in the summer of 1949, on a beach at Fishers Island where he soon was pointing out the sights to be seen if one had the wit to see them—seven or eight species of seabird inshore and offshore, the likely change in the weather inferred by the wind veering around to the south, the Latin name for a nearby snake or crab, the probable catch in the hold of a trawler bearing east by north on the far horizon.

The meeting had been called by my godmother and Peter’s father, long-abiding friends whose houses on the island were a short distance from one another; by both parties it was thought that Peter could tell me what to look out for at the Hotchkiss School, from which Peter had graduated in 1945 and at which I was a member of the class embarking upon its lower middle year. I was fourteen, Peter seven years older, a senior at Yale tormenting himself with the ambition to become a writer of important books. Literature in those days was understood to be a noble calling, the high and not easily traveled road to light and truth.

The first question put to Peter about Hotchkiss proved to be the last. He didn’t wish to discuss what he deemed to be an ornamental pillar of the bourgeois status quo, and so as the afternoon went on (many fish to be seen and named, further sightings of sandpipers and gulls) I was surprised by the likeness of his interests and turns of mind to those of Mr. George Van Santvoord, the headmaster of the school with whom Peter seemed to share not only a love of words and nature but also the courage to lead an examined and examining life. Before the day was done I’d compounded the likeness of Mr. Van Santvoord with that of the druid, Merlyn, in T. H. White’s The Sword in the Stone, one of the books on the school’s list of suggested summer reading. By the time I returned to the lamps being lit on my godmother’s sundeck, it had occurred to me that Peter’s teachings on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean not only resembled those of Mr. Van Santvoord’s to the Hotchkiss woods squad but also those that under the walls of Camelot Merlyn had vouchsafed to the young King Arthur:

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlyn, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That is the only thing that never fails … you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honor trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then—to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

The entirety of Matthiessen’s page in the Misch. Click to enlarge.

Which was the lesson that the young Peter Matthiessen developed into both a life and an art. Over the course of his long, shape-shifting day in the sun (1927–2014) he never stopped asking questions; it was his fierce and passionate will to know and understand that prompted him to try his hand as a naturalist, an explorer, a novelist, a Zen Buddhist, a journalist, a commercial fisherman, an investigative asset in Paris for the Central Intelligence Agency. From his travels high into the Himalayan mountains and low under Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, through the jungles of Peru and across the frozen desert of the Arctic, he returned with reports—on the Snow Leopard and the Musk Ox, on the banyan tree and the Great White Shark—that placed him, together with Henry David Thoreau, Annie Dillard, and Loren Eiseley, in the front rank of American writers illuminating the book of nature.

Peter’s novels wander around in the tropical swamp of man’s inhumanity to man, asking of the natives, himself among them, “Who is there?” The question seldom leads to answers suitable for framing in a college commencement speech or a state of the union address. The critics who praised Peter’s care for the music of words were careful to say that the force of his writing derived in no small part from his willingness to confront—look squarely in the face, acknowledge the reflection in a mirror—mankind’s vainglorious cruelty and greed.

The only American writer to receive a National Book Award for both nonfiction (The Snow Leopard, 1978) and fiction (Shadow Country, 2008), Peter once told an interviewer that prose held captive to the facts “cannot fly,” but there were poetic exceptions to the rule when the subject was the oriental crane (red-crowned, white-naped, or golden-eyed) for which Peter had a particular affection and in search of whose breeding grounds Harper’s Magazine, of which I was then the editor, sent him in 1992 to the Siberian basin of the Amur River.

Since our first meeting on Fishers Island we had stayed intermittently in touch within the company of writers and editors gathered around the center of literary gravity that was George Plimpton’s Paris Review. Peter in 1953 had joined in the founding of the journal that also served as his cover for what he later called the “youthful folly” of his brief stint with the CIA. Plimpton as the editor in 1956 moved its headquarters tent from a barge in the Seine River moored to a quai four miles downstream from the Louvre to his Manhattan apartment on East 72nd Street alongside the East River, six miles upstream from the Brooklyn Bridge, and for the next half century, while the Review published the major American writers of the second half of the twentieth century, among them William Styron, Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, Evan Connell, Terry Southern, Irwin Shaw, and Peter Matthiessen, the apartment was where, sooner or later, everybody went to help out with the drinking, rejoice in the favor of attentive young women, steal from one another the secrets and sorrows of Grub Street, add fuel to the fires of their ambition and pride.

For fifty years no week went by in which George didn’t give at least one party (sometimes preceded by invitations, more often not) in praise of a newly-published issue or book—a first novel, a volume of essays, an interview with W. H. Auden, James Baldwin or Ernest Hemingway, an epic poem, a revised biography, a collection of short stories, a translation from the Medieval French.

It didn’t matter how many people were present—sometimes twenty-odd, sometimes upward of two hundred—nor did it matter whether any famous authors were to be found, like Easter eggs, asleep under the piano or passed out on the pool table. People didn’t come with the thought of reading their names in the next day’s papers. They came for the fun of it, drawn to the light of George’s insatiable curiosity and irreducible enthusiasm. Peter possessed the same adventurous and life-grasping spirit, forever asking questions, relentless in his rage to know why the world wags and what wags it.

Over the years at the 72nd Street address Peter spoke of many things—of bears and pack mules and Richard Nixon, of Cesar Chavez and Ronald Reagan and Crazy Horse—and as he grew older, and the lines drawn on his time-worn but still handsome face more deeply set, I was more often reminded of his likeness to both Mr. Van Santvoord and the druid, Merlyn. I came to know him well enough to know that more than once he’d lost an only love, that he’d seen a great deal of the world about him devastated by evil lunatics—by the stupidity of the war in Vietnam, and the selfishness of America’s moneyed classes, by the ruin of his beloved biosphere at whatever compass bearings could be sold for a handful of silver—but also well enough to know that he never forgot that the best thing for being sad was to learn something. He published thirty-three books, the last of them In Paradise, a novel coming forth from the press during the same week in April 2014 that he died, at the age of eighty-six at home in Sagaponack, Long Island, on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean.

Lewis Lapham is the editor of Lapham’s Quarterly.

Smack Talk, and Other News

The wry, D.I.Y. branding of heroin. Photo: Graham Macindoe, via Wired

In celebration of its many contributions to arts and letters, Boston has approved a plan to turn a section of the city into the first-ever Literary Culture District. “Plenty of respected (if banal) institutions supported the effort to turn downtown Boston into a literary district … What’s baffling, though, is the metrics by which we’ve decided to judge their progress—more plaques, more street fairs, and more statues, not more writers, more affordable apartments, and more books.”

Among the many anti-Amazon domain names owned by Amazon: www.fuckamazon.com and www.boycottamazon.com. Your dissent will not be tolerated, peon.

Elif Batuman on awkwardness, America’s latest bugbear: “We have a hand signal for awkwardness, and we frame many thoughts and observations with ‘that awkward moment when … ’ When did awkwardness become so important to us? … ‘Awkward’ implies both solidarity and implication. Nobody is exempt.”

Apocalypse fiction as immigrant metaphor: “The same way X-Men comics are sometimes considered as representations of the American civil rights movement, the apocalypse genre represented my shifting understanding of ‘home’ … For immigrants, solitude and the trap of memory are central conditions. The appeal of [apocalypse fiction] is that it renders this so finely.”

The art of drug branding: the haunting, grimly comic logos on baggies of heroin. “References in the names reflected the addict’s illusions of grandeur (So Amazing, Rolex, High Life) but also the insidious destructive nature of drugs and the ultimate endgame (Flatliner, Dead Medicine, Killa).”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers