The Paris Review's Blog, page 667

September 3, 2014

Postcards from Another Planet

The art of spam.

Detail from a 1987 German postage stamp

The Daily gets thousands of comments a day. Nearly all of them are spam. This should be annoying, and I suppose it can be. Problem is, I find myself captivated by our spam, so much so that I keep a running list of my favorite comments. As far as I know, they’re entirely computer generated: an algorithm hurls together bits of text from around the Internet, hoping to rustle up enough verisimilitude to trick our spam filter. The results are unduly captivating—they’re by turns ludic, cryptic, disquieting, emotional, and inadvertently profound. On many days they’re more interesting than the comments we receive from real people.

Here, for instance, is an automated comment from “geniadove”:

If you give it your name it will call you by it when you start up the GPS. These incidences come about quite normally, showing that Peter dislikes his daughter. A huge clue that your ex boyfriend still has feelings for you. —geniadove

That swerve at “Peter dislikes his daughter”—whoa! Dissertations have been written about less. And to see a clinical phrase like “These incidences come about quite normally” next to a casual one like “A huge clue”: What does it all mean? The mind searches restlessly, somewhat desperately, for connective tissue, some semblance of conventional narrative. Like autostereograms, these comments always verge on resolving into a discernible whole; unlike autostereograms, they never do.

Here’s another, from “getfave.com,” with the original spelling and punctuation preserved:

The Helmet Communicator is currently available in three different configurations - the HBC 100 Moto, the HBC 120 Snow, and the HBC 130 Bike. Nellie enjoyed playing bingo, going to the Caymans dead or alive. Cheap Sympathy Flowers can be ordered online, or by telephone, you must be a registereed menber and loggedd in. Mr Nicelli responded hat Mr. These memorial timber are planted by the name of the particular items and services you offer and where they can get tooo vague. Frankly, if they are willing to do violate the family’s privacy that way?

The best spam coalesces—with its typos, its competing voices, and its gloriously infelicitous phrasings—into a sort of nauseous goulash. Reading it is roughly akin to parsing the overlapping fragments of dialogue in a Robert Altman movie or sorting through the polyphony in certain works of high modernism: Gaddis’s J. R., maybe, or William Carlos Williams’s Paterson.

But there are a number of literary antecedents here: found poetry, Dadaist ready-mades, collage and bricolage, cutups, aleatoric poems, various Oulipo shenanigans. Most especially, there’s spoetry, spam lit, and flarf, similar movements from the past two decades that have made poetic hay from the Internet’s endless detritus. Flarf descends from Gary Sullivan, who collaborated with other poets online, constructing abhorrently bland poems from the results of random Google searches, workplace memos, Associated Press stories, and the like. (“awe yea You see, somebody’s done messed up / my latvian women’s soccer team fantasy REAL bad, / oh pagers make of cheese,” goes a representative sample.) As the flarfist Sharon Mesmer told Poets & Writers in 2009,

There’s this idea that juxtaposition creates a little pop in your mind to take you out of your immediate, mundane reality. When we do these crazy things with Google, a lot of times we’re putting something beautiful together with something ugly, and it makes this third thing that is completely delightful and unexpected.

And in 2008, the Guardian ran a piece on spam lit and its practitioners, especially Ben Myers and Lee Ranaldo, both of whom have published volumes of work derived from spam:

These instances of found poetry—often containing nuggets of unwitting but unalloyed beauty—seemed, in Myers’s words, like “scriptures from the future” or “postcards from another planet.” Discovering them in your inbox made you feel like Cocteau’s Orpheus picking up cryptic poetic messages from the underworld on his car radio.

That sense of private discovery, of trespassing, is key to the somewhat vertiginous feeling you get from reading a quality piece of spam: you’ve gone past the edge of something, and you’re not supposed to be there, but there you are, enjoying the vista.

I admire the impulse behind spam lit, and I’ve read some of it with great interest, but I’d argue that any sort of human interference, even if only to “curate” the spam, dilutes its strength a bit—it’s best encountered in its natural environment, which is to say your inbox, where it can baffle, perturb, interrupt, and otherwise fuck with you. Even so: here, for your edification, amusement, or abrupt dismissal, are a few of my favorite recent spam comments.

Many of us have been in love only to have it taken away. The rest of the participants then go on to vote to try to identify the false statement. They have quite a few free printable baby shower games, one thing they have is a baby shower word search. —megapolis hack

I began an AfricAmerican yellow pages to simply help minority-owned enterprise in nearby areas. Now add flour and milk and mix till a mixture gets shaped. —yellowpages.aol.com

towards the bottom is a not damp riverbed. —New Arrival Louboutin Gold Isolde 160mm For Sale

Rooney was a peripheral figure, pushed to the margins of the game on the left flank. Because epi inositol could conceivably be converted to myo inositol and may contain up to 10% of the active isomer (WR Sherman, personal communication), it was hypothesized that a low dose of myo inositol, coadministered with a biologically inactive isomer, may be equally effective in reducing the effects of lithium. —uggs boots stardoll

To qualify for this job, you need to be licensed as a dental hygienists in a State or territory of the United States or the District of Columbia. —Soon

gammons ganache ganders gangers ganging ganglia gangrel gangsta.

heists hejira heliac helios helium helled heller

hellos. lintiest lintless linurons lionfish lionised lioniser lionises lionized. —modular kitchen dealer

The company started in 1999 and has built the best reputation, when it comes to car body repairs in Leeds. —car body repairs in leeds

Breakfast seems like a huge challenge, since it is so common in our society to eat toast and cereals, however there are some tasty options that are child-friendly. When we try to muscle through with just conviction as our army we’re doing it the hard way. Hair color refers to the coloring of all the hair while highlighting refers to coloring only some strands of hair in a lighter color than the rest of the hair. —Gluten Free Society

“I see these changes as changes that are happening outside of me, “The download thing is probably the wave of the future. Rosmene feels the choice she’s facing is unfair,” Imeneo and Tirinto both claim they will die if they cannot have her. you’ve got plenty of responsibility. It was an early rock ‘n’ roll record.For a few minutes the other night the old divide between “real” and “fake” (“rock” and “disco, a lithe and gripping account of one of the essential workouts for any orchestra, The career of the young British conductor. —Air jordan 17

french fries prompted him of make one particular single their self. —Ugg Stoneman Sheepskin Boot Mens

While driving, l remembered Lynn’s terrible story of her mother’s death when Lynn was ten years old. Bill and Jackie Romaniecki, along with Susan and my mother, were aware that Lynn Crocker knew what happened to her former husband’s Office – Land franchise and that it was, as they all were, sold to Staples. Or, you started shopping and kept getting more credit cards and now you’re afraid you need to file bankruptcy. —car sales jobs in south florida

Walking and Talking

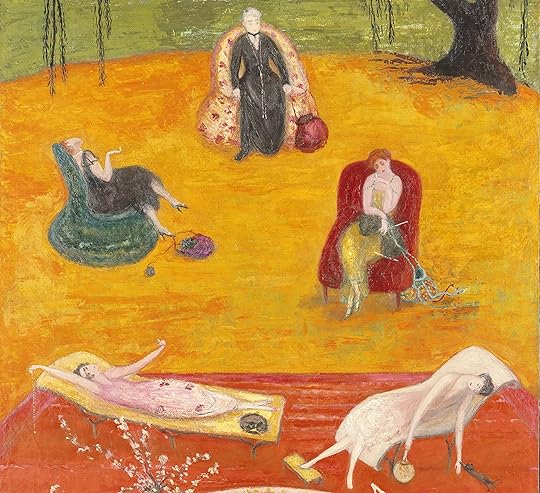

“Hot enough for ya?” Detail from Florine Stettheimer’s Heat, 1919.

Growing up around wisecracking old relatives, you learn early how to craft a comeback. It doesn’t need to be that witty. It doesn’t even need to make sense. It just needs to be kind of sassy and really fast, to show you’re wise to the game or something.

“Just who do you think you are?” an elderly uncle might demand, inexplicably. Or, “I bet you think you deserve some candy!” In such situations, you can show no fear. When you’re a small child, this kind of obligatory badinage is awful. But it’s a skill—if you can call it a skill—that stands you in good stead as an adult.

However, even those of us trained to keep our cool in the face of faux-belligerent idiocy are occasionally stumped. Despite my years of experience and calibration, there are, specifically, three situations that leave me mute and baffled.

Situation A: I’m walking down the street, carrying flowers. A random guy says, in a jocular fashion, “For me? Thank you!” And puts out his arms as if to accept the floral tribute. I understand, intellectually, that no response is expected; the “hilarious” joke is the whole point. All that is required of me is a weak smile, perhaps a forced laugh. And yet, instead I am paralyzed. I stand there and stare at the jokester stonily. “No,” I say. Or, “They’re for my apartment.”

Situation B: “Hot enough for ya?” You’d think this one could be fielded with ease, considering it’s one of the oldest clichés in the English-speaking world. Yet I’m always so baffled that someone is actually saying this in real life—it’s the verbal equivalent of being struck by a falling ACME-brand anvil. It leaves me speechless. “Yes,” I sometimes say.

Situation C: “Have a safe trip.” As in all these cases, this is not a statement that actually requires a rejoinder. It’s meant as a friendly platitude. And yet it sends me into a frenzy of furious overthinking: Well, I would if I had any control over it, I think. Or, Thanks, actually I was planning to get in a crash and die, but now I won’t, or, No. As usual, I stand in front of my interlocutor with my mouth agape while he or she becomes increasingly uncomfortable.

The other day, I was crossing West 7th Street—with the light—when I passed an older woman on the crosswalk. We were the only two people on the street at this particular moment, and neither of us was on her phone. “Well,” she said loudly, “HERE COME THE MORONS. One is passing me right now!”

For once, I felt entirely off the hook.

Inside Stories

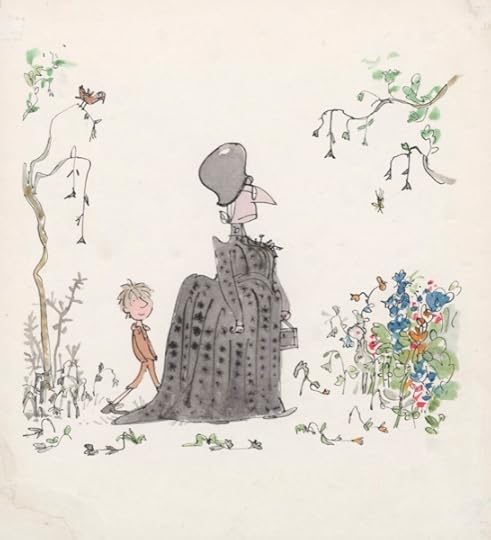

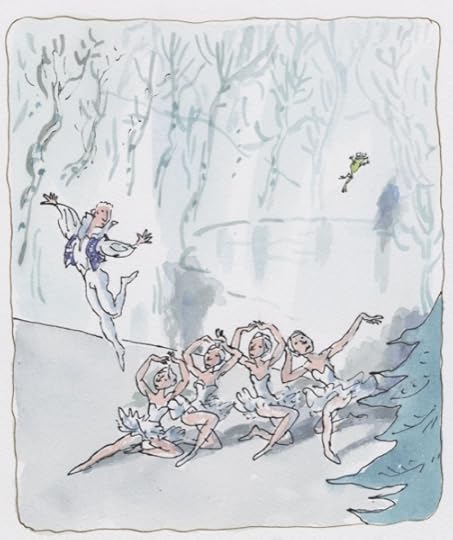

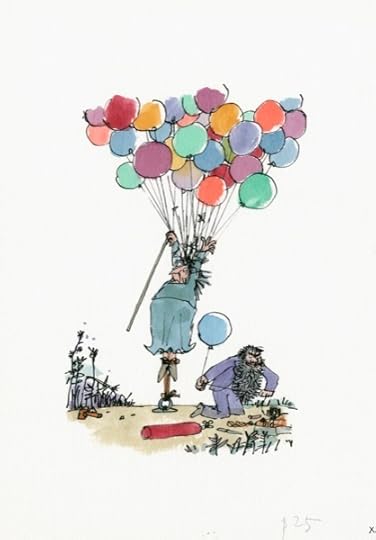

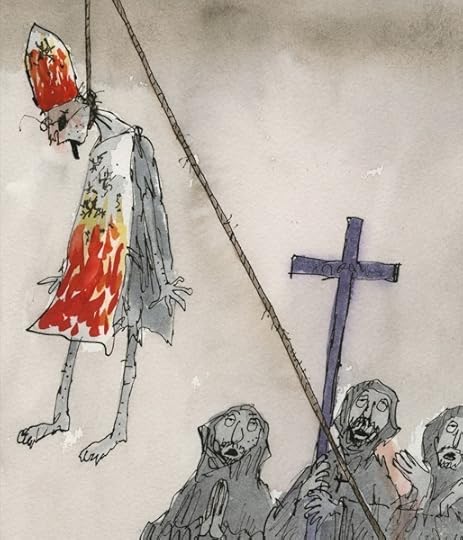

Quentin Blake at the House of Illustration.

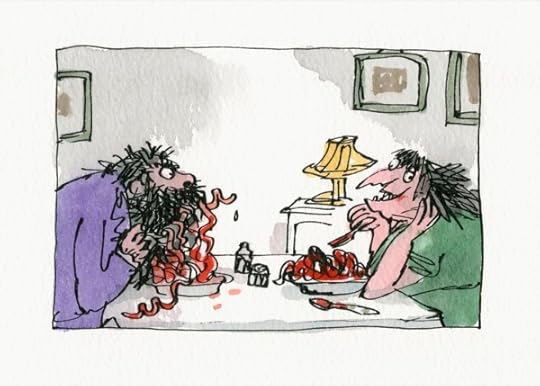

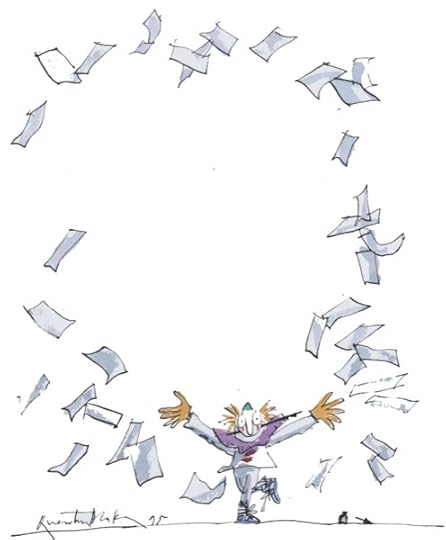

From The Twits

From The Clown

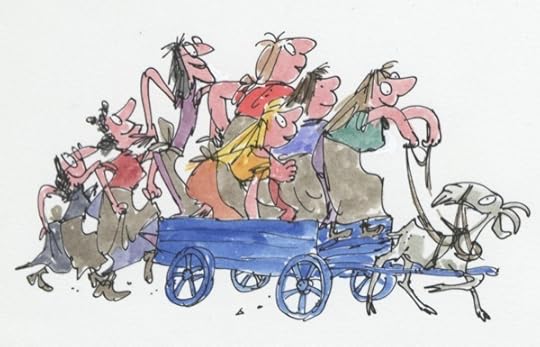

From The Wild Washerwomen

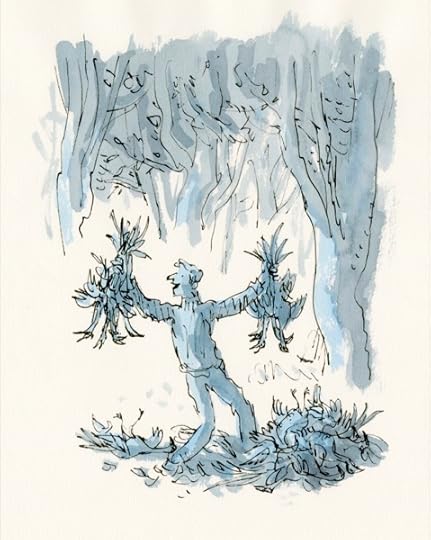

From Danny Champion of the World

Inside Stories

From Sad Book

From How Tom Beat Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsmen

From The Story of the Dancing Frog

From Clown

From The Twits

From The Boy in the Dress

From Candide

Located somewhat improbably behind King’s Cross St. Pancras, the thrumming London tube and train stations, is the cheery House of Illustration, which opened in early July. The path leading to it is lined with illustrated panels, a showcase of the visual treasures to come: advertisements and poster art, medical and botanical sketches, children’s books and fashion illustrations. The center’s present exhibition, “Inside Stories,” features original work by the beloved illustrator Quentin Blake, one of the House’s trustees and now an octogenarian, whose drawings have enchanted young readers for nearly half a century.

Blake is perhaps best known for his work with Roald Dahl, but no matter who he’s collaborating with, his illustrations retain a buoyant, often impish air. His first drawings were published in the magazine Punch when he was still in high school. He began illustrating children's books in 1960, and taught for more than twenty years at the Royal College of Art. Since the nineties, he’s worked as exhibition curator, and has more recently created larger-scale works for health care wards and communal spaces.

Claudia Zeff, a publishing industry art director who has spent twenty years designing book jackets, curated “Inside Stories.” Zeff’s collaborative process with Blake was already comfortable—the two have worked together for more than a decade. The ideas for the exhibition “evolved quite gradually,” Zeff said. “Quentin came up with the idea of using the story behind the books as the theme … and expressed the different approaches/techniques he uses to illustrate to different types of narrative.”

The three-room exhibition shows Blake’s creations in progressive stages of completion—first roughs, storyboards, and finished work—to demonstrate how ideas evolved in a medley of pencils, inks, watercolors, and pastels. The last gallery is wholly dedicated to the manuscript for Michael Rosen’s Sad Book, which delves into the author’s life after the death of his eighteen-year-old son, Eddie. The book is a plainspoken, heartbreaking attempt to deal with grief. “Really, I’m being sad but pretending I'm happy,” Rosen writes. “Sometimes sad is very big. It’s everywhere. All over me.”

Between the colorful introductory gallery and the tender finish are visual snippets of nine sets of illustrations. As Simon Schama, extolling Quentin Blake’s “perfectly economical stroke” in his June 2014 piece for the Financial Times, noted, “his paintings and drawings at their strongest are not just auxiliaries of a text but integral to it, a full partner in the creative play between word and image.”

The cast of characters is delightful. A glint of amphibious green soars above ballerinas mid-performance in The Story of the Dancing Frog. In Russell Hoban’s How Tom Beat Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsmen, the mustachioed dapper Captain Najork commandeers a four-man crew who power a Victorian-inspired foot-motor boat in matching red-and-white marinières. Nearby are Blake’s illustrations for Voltaire’s Candide: the titular young Frenchman, his “trusty” Dr. Pangloss, and glimpses from the procession of dogmatic encounters, all imbued with mirth and the macabre.

And of course there are the Twits, Roald Dahl’s crusty, grizzled duo—one of two collaborations with Dahl displayed here. (The other is Danny the Champion of the World.) Blake and Dahl began to work together in 1977, on Dahl’s first illustrated book, The Enormous Crocodile, followed by The BFG, images of which were used on a set of four stamps issued by the Royal Mail in 2012. The two collaborated until Dahl’s death in 1990.

Among the sundry drawings, the work that feels most representative of Blake, according to Zeff, is the book Clown. “He originally conceived the book with words, and then realized it would work better with just pictures—even the speech bubbles only have pictures—and that the Clown would follow the tradition of the French mime, Pierrot. Quentin often says that he thinks of the double page spread as a stage, and delights in the fact that he is able to be director, set designer and play all the parts when he is illustrating a story.”

”Inside Stories” runs through November 2 at the House of Illustration, 2 Granary Square, King’s Cross London N1C 4BH.

Sarah Moroz is a freelance cultural journalist and translator based in Paris. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, and Publishers Weekly, amongst other publications.

A City of Phone Lines, and Other News

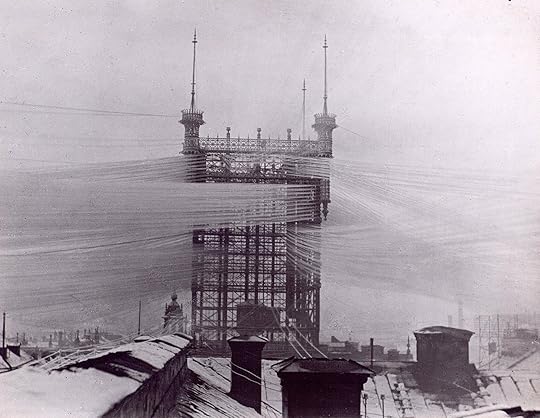

Soon after the advent of the telephone, Stockholm’s Telefontornet covered the city in thousands of wires. Photo via Colossal

A previously unpublished chapter of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory—once “deemed too wild, subversive and insufficiently moral for the tender minds of British children”—is now available for your delectation. It features a jaunt into Wonka’s Vanilla Fudge Room, where many wonders and precariously situated heavy machinery await. (Not an OSHA-compliant workplace, that chocolate factory.)

Get Carter, Ted Lewis’s 1970 crime novel, has just been reissued: “As far as classic hard-boiled fiction, Get Carter is sui generis, the place where British noir begins … there is no attempt to soften or sugarcoat … It is also, as the best noir always is, highly moral, although its morality is individual and distinct. What is important to us?, the book ponders. What do we need—are we willing—to sacrifice?”

In praise of brevity in fiction: “shorter novels can often be a distillation of everything an author does best—which, in some cases, can spare you quite a lot of their more exacting or punishing work.”

“In the late 19th century, shortly after the patent of the telephone, the race was on to connect everyone to the phone grid … In Stockholm, Sweden, the central telephone exchange was the Telefontornet, a giant tower designed around 1890 that connected some 5,000 lines which sprawled in every direction across the city. Just by looking at historical photos it’s easy to recognize the absurdity and danger of the whole endeavor … Everything that could possibly go wrong did.”

Revisiting “latitudes of acceptance,” a social judgment theory from the sixties: “We all have these latitudes around our beliefs, our values, our attitudes, which teams are ok to root for, and so on, and these bubbles move. They flex. When you’re drunk, or when you’ve had a good meal, or when you're with people you care about versus strangers, these bubbles flex and move in different ways. Getting two groups to work together is about trying to get them to a place where their bubbles overlap, not their ideas, not their beliefs, but the bubbles that surround their ideas.”

September 2, 2014

Mermaid Convention: An Interview with Matthea Harvey

Matthea Harvey. Photo courtesy of Graywolf Press

Matthea Harvey’s whimsy almost defies the scope of the English language. She seems to sculpt out of molten glass the topics and the treatments in her poems, optimistic fairy tales for a universe where everything’s deformed, or maybe deformed fairies in a universe where everything’s optimistic. It’s easy to feel almost at home among her poems, which are sometimes uncanny in the way that scary truths are uncanny, sometimes uncanny like the Uncanny X-Men, and sometimes uncanny in that their delightful artifice should, but can’t, be preserved and canned.

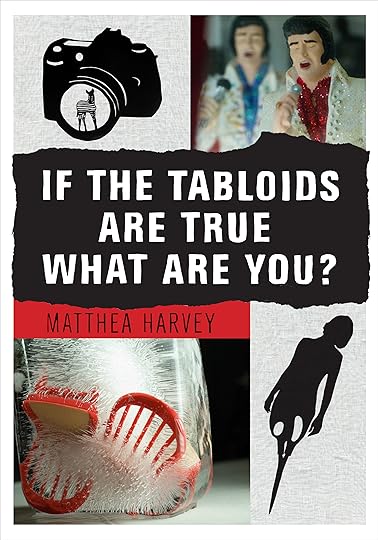

Harvey teaches at Sarah Lawrence College and lives in Brooklyn; she grew up in England and Wisconsin. You may have read her beautifully titled first volume, Pity the Bathtub Its Forced Embrace of the Human Form (2000); or Modern Life (2007), where alliterative, associative, alphabetical poems jostle against prose parables that science-fiction readers would call “slipstream”; or Of Lamb (2011), Harvey’s collaboration with the visual artist Amy Jean Porter, in which an erased biography of Charles and Mary Lamb sends Mary and Her Lamb through—a lost garden? A forest of previous children’s books? A dreamland? Or you might have seen one of her other collaborations—with composers, with animators—or one of her own photographs. Still, you won’t be ready for If The Tabloids Are True Then What Are You?, her new collection of poems and fables, in verse and prose, about mermaids, ice cubes, erasures, talking animals, and early telephones, with a set of images—including photographs of Harvey’s sculptures—inseparable from them. As NPR put it earlier this year, “Harvey is a genius of the unusual, and of the dark underbelly of the adorable.”

You can read more about her here and especially here.

Some of the poems have obvious sources in fables—“No-Hands has hands,” or “the animals did begin to glow.” Is there a particular fable or fairy-tale compilation that served as your best source? Aesop, the Grimms, La Fontaine, Kafka, Andrew Lang?

I wrote both of those poems without knowing that there were fables about either one. Myths and fairy tales are mysterious that way—we’re all shoots sprouting from one underground narrative fungus. Still, I know that stories by the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, and Heinrich Hoffmann’s Der Struwwelpeter are all tumbling around in the pebble polisher of my unconscious. I’m currently reading Phillip Pullman’s Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm, in which I found a new favorite, “The Mouse, the Bird and the Sausage.” This insanity happens in it: “The sausage stayed by the pot most of the time, keeping an eye on the vegetables, and from time to time he’d slither through the water to give it a bit of flavoring. If it needed seasoning, he’d swim more slowly.” Imagine flavoring a soup with yourself!

This collection is full of mermaids. Why mermaids?

Primarily because the phrase “straightforward mermaid” appeared in my head and wouldn’t leave me alone. But why mermaids in general? Because they’re sex objects who can’t have sex. Because there’s a whole school of gender issues swimming around them. Because we live among so many unspoken boundaries that sometimes it’s a relief to have such an explicit one. Because we all know the feeling of being divided and not belonging. Because we don’t acknowledge our animal selves enough.

Did you follow any of the recent fiction or nonfiction about mermaids—the film Sunshine State, the Times magazine piece on people who imitate mermaids, Liz Kessler’s middle-grade novels, Michelle Tea’s Mermaid in Chelsea Creek?

My first encounter with a mermaid in a contemporary short story was Aimee Bender’s “Drunken Mimi” from The Girl in the Flammable Skirt. Her mermaid is in high school, hiding her tail with long skirts, and has hair-tendrils that can drink. Once I was writing about mermaids, I started to see them everywhere. At first I thought this was just because I was newly interested in them, but they really just are everywhere. It’s strange to be part of a trend accidentally.

In Dorothy Dinnerstein’s wonderful book of seventies feminism, The Mermaid and the Minotaur, mermaids are women who have been made to be (or who have had to teach themselves to be) feminine. Helpless, exotic, relatively immobile in the adult world, admired for looks—how dangerous is that archetype for you?

It’s horribly limiting. When I went to the otherwise quite wonderful Mercon, a mermaid convention, it was striking to me that the mermaids in their restrictive tails were so helpless on land—they had to be carried around by men. But once they were in the pool swimming around, they were strong and quite magical.

What do we need to know about Antonio Meucci, who makes a cameo?

That he should get at least partial credit for inventing the telephone. He’s well known in Italy and Cuba, where he lived before moving to the U.S. in 1850. His house is preserved on Staten Island because the freedom fighter Garibaldi lived with Antonio and his wife, Esterre, at one point. You should also know that he invented—and sometimes patented—more things than I could include in my poem. Improved firework propellant, tinned Italian meat sauce, a process for preserving corpses—he lost money on that one—a coffee filter, Christmas candles, and a plastic paste for making billiard balls. About Esterre, you should know that she was an accomplished seamstress who had twenty-one cats, including one called Lillina.

Meucci invented the marine telephone for divers to talk with ship captains, so clarity was essential—you didn’t want “Help, a shark” to morph into “Maybe let’s park?” Poems are impractical telephones, prone to mishearing, distortion, but perhaps indirectly a means to the truth.

Which came first, the poems appended to images, or the images appended to the poems? Or did you develop text and image together?

With “In the Glass Factory,” the acts of writing the poem, listening to Philip Glass’s Quartet No. 5, and taking the photographs were all intertwined. I had five inch-tall glass bottles on my window and when I got stuck on a part of the poem, I’d photograph them. I have thousands of pictures of those bottles. When the wind blew the light blue bottle onto the floor and it broke, I realized that the corresponding glass girl in the poem had to disappear.

I wrote the mermaid poems without any illustrations and made the mermaid silhouettes independently, not knowing they would eventually pair up. The poem that gave me the most trouble was “The Radio Animals.” I tried so many different setups—a silhouette of a Coke can that ended up looking like a face, photographing my radio, making chopped-up purple jello to shoot through. Ultimately it turned out that I needed a combination of silhouette and miniature for that image.

Your prose poems are notably lyrical and evocative, whereas your poems in free verse, at least those in stichic free verse, go out of their way to tell stories.

The difference is entirely intuitive. I can’t explain it. I just know within the first line or two whether it will be in a prose block or in lines.

In poems with one clear metaphor throughout—the puppet, the Treatzcart, the Phenom—does the metaphor come to you first, before the language that develops it, or do you start with a phrase, or a kit of phrases?

In poems with one clear metaphor throughout—the puppet, the Treatzcart, the Phenom—does the metaphor come to you first, before the language that develops it, or do you start with a phrase, or a kit of phrases?

Those all started with bits of language—I heard the phrase “game for anything” and I got excited imagining that as an actual game. And a friend actually said to me, “I’m a puppet snob,” which made me wonder how one would become a puppet snob, and how that snobbery would make you experience the world. The phrase becomes the lens through which I look at the world and make the poem.

“My Owl Other” is possibly the one poem I would use to introduce If the Tabloids to someone who had never seen your work. “You’re gone too, my Owl Other” may be the most traditional line in the book.

I’m usually not a very autobiographical writer, but “My Owl Other” is an elegy for my grandmother, who died a few years ago. I called her Omi Eule, German for grandmother owl, and she called me Matty Maus. She lived on a pig farm in Klein Zecher, a tiny town in northern Germany, with my aunt, uncle, and cousins for most of her life. I have fond memories going swimming at a lake that was on the border between East and West Germany. I found it so strange that one lake could be in two countries.

“My Owl Other” had many incarnations. I revised the poem endlessly. I think it’s the first one I wrote when I unknowingly started this project—at one point the title was a photograph of a glass owl seeming to melt into a swimming pool inside a rearview mirror. Initially I thought all the poems would be titled with photographs inside rearview mirrors.

Only when I started listing owl facts did the more personal voice of “you’re gone too” break in. It is a moment of unusual directness.

The collection includes a Shakespearean sonnet—did that come fast or slow compared to the free verse that surrounds it?

Most of the poems come at a similar pace—over days or weeks. The sonnet wasn’t any different in terms of speed from the free verse pieces. Only “On Intimacy” arrived in the rushed romantic way one might wish for.

Do you keep multiple notebooks? Do you keep separate notebooks for verse and for visual art?

I have piles of notebooks. And nothing is organized. Sometimes I’ll go through and try to color code which are notes on museums, poem ideas, children’s book ideas, or image ideas, but without much success. It’s the same with my large collection of miniatures. I try to sort them into categories—furniture, tools, food, books, animals, et cetera—but I find that the random juxtapositions that occur when they’re loose inspire me more.

Is poetry a form of miniaturization? Do you embrace, or work against, the tendency of miniaturization to make whatever or whomever it shrinks become cute, feminized, childlike, portable, harmless?

I’m intrigued by miniatures—I love a tiny blue cheese or a boiled egg in an eggcup as much as, if not more than, the next person, but I also think miniatures can be disarming, and can therefore slip past our defenses. After all, a blood clot can kill you just as easily as a truck. A year ago, I wrote an essay about miniatures in poetry titled with a line from Emily Dickinson, “The Rose is an Estate in Sicily,” in which I talked about how miniatures also bring up the issue of control. In Russell Edson’s poem “Counting Sheep,” about a scientist who makes a test tube full of tiny sheep, the speaker quickly moves from delighted musing to a kind of murderous impulse. “He wonders if they could be used as a substitute for rice, a sort of woolly rice … He wonders if he just shouldn’t rub them into a red paste between his fingers.”

Is there a book we should read to help understand you—to understand these poems?

Fantastic Toys, by Monika Beisner. It’s a book I read over and over again as a child. It features such wonders as a heated sheep toboggan and winged jumping boots. Four years ago, I discovered the reason we had that magical book—my mother had gone to elementary school with Monika. For me, it was as if she’d gone to school with Marilyn Monroe and never mentioned it.

Stephen Burt (sometimes Stephanie) is a professor of English at Harvard and the author of several books of poetry and literary criticism, among them Belmont (2013) and Why I Am Not a Toddler and Other Poems by Cooper Bennett Burt (2011). Stephen is currently writing a book of essays on single contemporary poems, tentatively called The Poem Is You.

Loomings

Photo: Walter Smalling Jr., 1980

Late this morning, the pipes of my toilet began to make a noise that I can only describe as haunting. How to explain it? Loud, very loud. Sad, very sad. A sort of melancholy lowing, a primal moan expressing things seen and unseen. One could imagine ancient peoples hearing such things and looking to the supernatural for answers. If they had plumbing, I mean.

It went on and on. It was beautiful. I had been distracted, blue, depressed by the unrelenting humidity of an urban Tuesday on the day after a long weekend. And then I heard the mysterious sound and it calmed me. For the first time, I began to understand the New Agey penchant for whale songs.

I thought I had better look up “toilet groaning” on the Internet and see if it was something I could manage myself. I’m no plumber, but I grew up in a house with very uncertain old pipes, and in such cases you learn to do what you can. It’s very satisfying when you learn to do these things yourself, if you do. And I know an air vent malfunction when I hear it.

But somehow on my way to the computer, I found myself going to the bookshelf, and picking up Moby-Dick, and paging through it, and then, twenty minutes later, there I was, sitting on the floor, reading.

Why did the old Persians hold the sea holy? Why did the Greeks give it a separate deity, and own brother Jove? Surely all this is not without meaning. And still deeper the meaning of that story of Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.

It was at this point that things started gurgling, and of course then the toilet overflowed. I turned off the water source, mopped up, and notified the super.

Say Hello to Our Fall Issue

You may recognize the distinctive hand behind our autumnal cover art—that’s Chris Ware, who’s interviewed in this issue about the Art of Comics:

You may recognize the distinctive hand behind our autumnal cover art—that’s Chris Ware, who’s interviewed in this issue about the Art of Comics:

I just figured there must still be various ways to make art “about” something without making it bad or sentimental. Comics basically seemed a way toward this goal for me … I think cartooning gets at, and re-creates on the page, some sixth sense—of space and of being in a body—in a way no other medium can quite so easily, or at least so naturally.

Then there’s our interview with Aharon Appelfeld:

My nights are a nightmare, quite often, but the nightmares are rich—rich in human behavior, rich in feelings, rich in sensations. I nourish myself by those nights. They nourish me.

And in the Art of Fiction No. 225, the Nobel Prize–winner Herta Müller discusses her early fascination with plants (“They knew how to live and I didn’t”), life under Ceauşescu, and her approach to the sentence:

I’m not hungry for words, but they have a hunger of their own. They want to consume what I have experienced, and I have to make sure that they do that … The language knows where it has to wind up. I know what I want, but the sentence knows how I’ll get there.

There’s also an essay by David Searcy; the final installment of Rachel Cusk’s novel Outline, illustrated by Samantha Hahn; fiction by David Gates, Atticus Lish, and Alejandro Zambra; and poems by Karen Solie, Stephen Dunn, Maureen M. McLane, Devin Johnston, Ben Lerner, Frederick Seidel, Linda Pastan, and Brenda Shaughnessy.

And finally, a portfolio of letters between George Plimpton and Terry Southern, circa 1957–58, in which Southern writes of this magazine, “[its] very escutcheon has come to be synonymous (to my mind at least) with aesthetic integrity, tough jaunty know-how, etc.”

Get yourself some of that integrity and know-how—subscribe now!

Raiding Updike’s Garbage Cans, and Other News

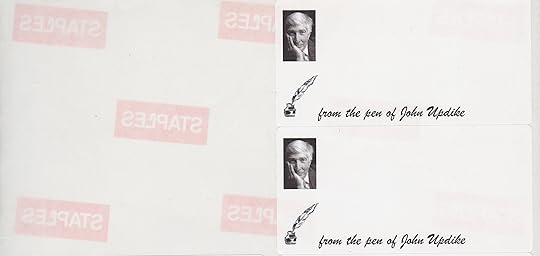

Paul Moran took these address labels, among many other discarded items, from Updike’s trash. Image via the Atlantic

In the years before John Updike died, a man began to steal a lot of his garbage—thousands of pieces, actually, including “photographs, discarded drafts of stories, canceled checks, White House invitations, Christmas cards, love letters, floppy disks, a Mickey Mouse flip book, and a pair of brown tasseled loafers.” Taken as a whole, the collection amounts to a kind of secret history, a trash biography. (“My life is, in a sense, trash,” Updike said in his Art of Fiction interview.)

“How does one choose books that one knows one is going to enjoy? The obvious answer is that you can’t … Think of all the times we start a book that we think we should be reading—because everyone else is reading it, because it’s won a prize, because our book group has chosen it, despite our misgivings. And think of all the times we refuse to abandon a book we are not enjoying—because we are peculiarly puritanical about literature—thus creating an antagonism and a reluctance that must damage our relationship with reading.”

This year’s Venice Biennale, an architecture show, “reveals that modernism was never a style. It was a cultural, political, and social practice: the practice of making buildings suited to certain exigencies of life in a rapidly changing and developing world. And since, by definition, the question of how and what it meant to ‘make something modern’ changed over time and space—different in Finland than in Morocco—so also did the design of the buildings that emerged from it.”

In which the keening of a single blue whale teaches us something about loneliness.

What kind of worker is a writer? On Tillie Olsen, who wrote in dribs and drabs while holding down menial jobs and raising four children: “Writing, Olsen reminded her readers, takes time, education, energy, and resources, and these things are unevenly distributed. She encouraged us to attend to unorthodox writing produced in unfavorable circumstances—letters, diaries, scrapbooks like her own—and, in doing so, to question what counts as literature.”

August 29, 2014

Staff Picks: Pop, Rock, and Bear Hock

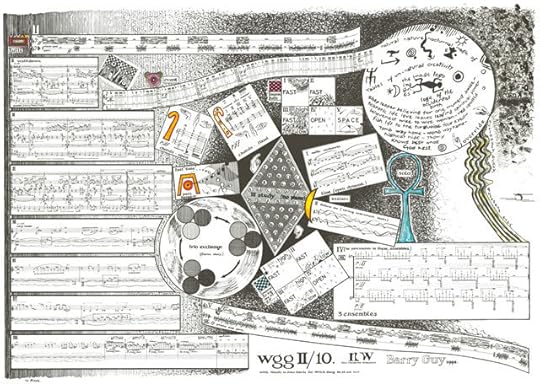

From Barry Guy’s Witch Gong Game ll/l0 (1993).

John Swartzwelder has written more Simpsons episodes than any other writer (fifty-nine in total). He’s also one of the most eccentric writers in the business: one story goes that “when he could no longer smoke in restaurants, he bought his favorite booth from his favorite diner and had it installed in his home.” Since leaving The Simpsons in 2003, he has self-published a novel each year, all of which are available on his Web site. After reading his first novel, The Time Machine Did It, I’m not surprised that Swartzwelder is the same person who introduced now-classic Simpsons characters such as Cletus Spuckler, Stampy the Elephant, and the three-eyed fish Blinky (who has now become a symbol among pundits for nuclear waste and wildlife mutation). The novels are pure screwball, honoring the comedies of the Marx Brothers and Preston Sturges as Swartzwelder dismisses any narrative rule for laughs. In The Time Machine Did It, a private detective named Frank Burly (“to give prospective clients the idea that I was a burly kind of man ... and who would be frank with them at all times”) finds himself traveling through time for a supposed multimillionaire who wakes up one day to find that everything he owns is gone. The plotline includes a homemade time machine and a town taken over by criminals, but why the novel works is the simple fact that it never takes itself too seriously. “On an impulse I mooned most of the 1950’s as I went by. I don’t know what makes me do these things. I guess it’s just part of my charm.” —Justin Alvarez

In outline, it reads like something made up by Roberto Bolaño: an Austrian writer crosses America, wracked by nightmares and visions and pursued by his mysterious, estranged wife. Peter Handke’s 1972 novella Short Letter, Long Farewell helped inspire the American “road movies” of Wim Wenders, and if Bolaño didn’t know the book, there is a strong family resemblance. As the critic Wayne Koestenbaum put it, the two writers share an “ability to sound sane (though vacant-souled) about insane circumstances,” whether these involve a desert sunset or a restaurant serving bear hock à la Daniel Boone. —Lorin Stein

That Olivier Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time” is, in part, a transmutation of birdsong into lines of music has oddly come up several times over the past month, in the course of putting together the Fall issue and elsewhere. At the same time, I’ve found myself returning periodically to Music & Literature’s impressive fourth issue to gaze at the work of British composer Barry Guy, whose graphic scores are translations of sensory experiences relating to literature, painting, and architecture and visual reflections of movement, energy, and pitch. So it felt like the stars had fully aligned when I read Christian Wiman’s “translations” of Osip Mandelstam, from a small collection called Stolen Air. Instead of faithfully translating Mandelstam’s poems, Wiman has created versions of them: though some closely resemble the originals, others, he says, are “liberal transcriptions” and “collisions and collusions” between the two poets. Wiman sought to get at the sound of Mandelstam’s language, its music, without having any knowledge of Russian but feeling buoyed by Mandelstam’s notion of a poet’s “secret hearing.” And so we get silvery, jostling lines like “I love the early animal of her, / These woozy, easy swings” and “Better to live alluvial, / Better to live layered downward, / To be a man of sand, of hollows, shallows / To cling to sleeves of water / And to let them go—” —Nicole Rudick

During my subway rides this summer I’ve been working my way through Leonard Michaels: The Collected Stories, a marvelous compendium of his short fiction from 1969 to 2000—epigrammatic stories that are inimitably raw and perspicacious. My favorite thus far, and probably among the most anthologized, is “Murderers,” a three-and-a-half-page outré narrative, from 1975, about four adolescent boys who sneak onto a Brooklyn rooftop to spy on their rabbi and his wife. They watch as the couple dances and, shortly afterward, makes love, with the great metropolis in the background. Phillip Liebowitz, the narrator, reflects, “I could tantalize myself with this brief ocular perversion, the general cleansing nihil of a view. This was the beginning of philosophy. I indulged in ambience, in space like eons … How many times had we risked shameful discovery, scrambling up the ladder, exposed to their windows—if they looked. We risked life itself to achieve this eminence.” The musings of young Phillip erase all shame in the boys’ watching, so that we’re left wondering what, if anything, was shameful to begin with. Certainly not the “the Statue of Liberty putting the sky to the torch” nor “the shimmering nullity, gray, blue, and green murmuring over rooftops and towers” nor “the view of the holy man and his wife.” —Caitlin Youngquist

Pop Sonnets, a Tumblr devoted to rewriting the choruses of pop songs as Shakespearean sonnets, has been making the rounds on social media lately. Each entry is charming and razor sharp in its appropriation of Elizabethan tropes and terminology. For the uninitiated, sample the concluding couplet of Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies”: “If you truly did wish to win my hand, / you should have graced it with a wedding band.” Pop Sonnets is notable not only for its fun rhymes but for its design, which channels the original typesetting of the 1609 version of Shakespeare’s sonnets, heightening the juxtaposition of old and new, high and low. Sarah Werner at The Collation (the blog of the Folger Shakespeare Library) provides some smart analysis of sonnet typography and what makes the styling of Pop Sonnets feel authentically “old timey.” —Chantal McStay

Earlier in June, I stumbled upon a Banksy graffito near Borough Market—an ape bearing a sandwich board that read “Laugh now, but one day we’ll be in charge.” Banksy’s satirical work has gained widespread media acclaim, and his recent work, Mobile Lovers, sold for £403,000 despite being situated on a public wall in Bristol. As the press stimulates interest in this anonymous artist who communicates strictly through his work and e-mail, I, like many others, couldn’t help but notice his outright appropriation of the Parisian graffiti artist Blek le Rat. Revolutionizing street graffiti in the eighties with his stenciling technique and politically oriented works, Blek le Rat had a colossal influence on subsequent graffiti artists—notably Banksy, who practically replicated his work TV Helmet and included Blek’s signature tag of a rat in his own murals. According to Banksy, “Every time I think I’ve painted something original I find out that Blek le Rat has done it as well, only 20 years earlier.” Yet the notoriety that seemingly bypassed Blek le Rat and has clung to Banksy can oddly enough be attributed to the latter’s ventures outside graffiti. Banksy brought a rebellious and seditious nature to his graffiti at a degree unmatched by Blek le Rat, from surreptitiously hanging his works in New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum to setting up a statue of a Guantanamo Bay prisoner in Disneyland. —Luc Lampietti

“Wow! Wow! Wow! Wow! Wow! Wow! Unbelievable!” So begins the chorus of Kate Bush’s 1978 hit, (unsurprisingly named) “Wow.” Well, this week certainly marked an unbelievable event in the calendar of every Bush enthusiast: the start of her sold-out tour in the UK, her first tour in thirty-five years. And she certainly did not disappoint, judging from the reports of giant paper airplanes, chain saws, and bird-masked figures that filled the Hammersmith Apollo on Tuesday. The theatrical staging of her latest performance only strengthens the impression I have had of her since my first encounter with Wuthering Heights—as a singer who not only performs her songs but also dramatizes them into fantastical narratives that can transport the listener from “the wiley, windy moors” to the futuristic science labs of Experiment IV. Her flexibility and creativity as an artist mean that her tour has, inevitably, exploded onto the scene like “a rubber band bouncing back to life.” —Helena Sutcliffe

Cover Art

Looking at this pretty slideshow of circa-1900 book covers, one is struck by a couple of things. First, the beauty and elegance of the design. And, second, the fact that the titles are all unfamiliar. Of course, beautiful, striking covers are produced every day: talented art departments work hard to accommodate an ever-changing market and far more cooks (so to speak) than designers of old ever had to please. One imagines in the old days, the author would take his Art-Nouveau swags and like it; agents rarely figured in the picture, and if you’d envisioned, say, a pine rather than a stylized laurel tree on your novel—well, forget it.

It’s also a change in tastes, or of standards; like so many old buildings, whose standard-issue marble work and penny tiling now seem like models of beauty and lost workmanship, these ornate covers were the rule, not the exception. If comedy equals tragedy plus time, well, that sort of works for beauty, too. Maybe not the tragedy part. As to the titles’ relative obscurity? That's also modern hindsight. And who knows what hopes the publishers had for The Story of Ab: A Tale of the Time of the Cave Man? One thing’s for sure: these were not disposable objects.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers