The Paris Review's Blog, page 666

September 5, 2014

Staff Picks: Beard-Burdened and Beer-Branded

The Jeff Koons show has a little more than a month to go in its run at the Whitney Museum, and it’s been perplexing to see critics fall in with an artist whose work is the archetype of the money-driven art production about which many of them complain. To me, Koons’s work is all surface—literally and figuratively—and he seems to avail himself of Duchamp’s and Warhol’s legacies in order to promote, in art, wily marketing strategies gleaned during his years as a Wall Street commodities trader. It was a pleasure, then, to read Jed Perl’s assessment in The New York Review of Books. Perl rebuffs the idea that Koons’s work critiques middle-class values, concluding instead that it is the “apotheosis of Walmart” and “a habit-forming drug for the superrich” and that Koons is a too-confident exhibitionist. I find something immensely powerful in Perl’s tracing of the tradition of doubt in art—from Pliny to Michelangelo to Chardin—and in his conclusion that “where there is no doubt there is no art.” —Nicole Rudick

The story of Bluebeard, the wife-murdering aristocrat made famous in Charles Perrault’s seventeenth-century folktale, has captured the imagination of writers from the Brothers Grimm to Angela Carter. But William Thackeray’s lesser-known sequel to the hero’s bride-butchering, Bluebeard’s Ghost, tells the story through new eyes—specifically those of the final Mrs. Bluebeard, who escapes her husband’s clutches and goes on to inherit his estate. Pursued by numerous suitors, she opts for the equally hirsute “Captain Blackbeard, whose whiskers vied in magnitude with those of the deceased Bluebeard himself.” In true Thackeray style, he manages to transform a famously macabre narrative into a comic and playful study of human foibles, with the subjects inflated into caricatures of their former selves. Fittingly, September 5 marks the day that Tsar Peter the Great issued his “beard tax” of 1705, presenting those men determined enough to protect their hair with a hundred-rouble fee and a token bearing the words “the beard is a superfluous burden.” Thackeray’s tale is surely the other side of this coin: although his take on one of the most famous beards in literature is undeniably far-fetched, it is by no means a superfluous addition to the original. As he puts it himself, “Psha! Isn’t it written in a book? And is it a whit less probable than the first part of the tale?” —Helena Sutcliffe

If you’re looking to become productively, righteously, vindictively angry, read this piece in the Times about Crested Butte, Colorado, a town that will become, this weekend, an advertisement for Bud Light. Yes, entirely: “The town’s main thoroughfare, Elk Avenue, has been adorned with outdoor hot tubs, a sand pit, concert lights and a stage. Restaurants and hotels have been stripped of many local markings and given beer-branded umbrellas and signs instead. When the filming starts, drinks will be unlimited, access to the main street will be restricted to people with company-issued bracelets, and beautiful, mountain-ringed Crested Butte will be rebranded as ‘Whatever, U.S.A.’” The mayor made the deal in secret, for $500,000; his name is Huckstep. The whole thing seems like an episode from a lesser George Saunders story. One can react only with scorn, and then one must trot out that shopworn but ever more vital statement of Philip Roth’s, from 1961: “The American writer … has his hands full in trying to understand, describe and then make credible much of American reality … It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meager imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents.” —Dan Piepenbring

I could write about how much I’ve been watching the U.S. Open: how captivating the sport’s collision of intelligence and athleticism is, with its displays of raw emotion every time a player lunges to return a serve. But after reading Ben Rothenberg’s excellent essay on what it takes to be a line umpire, I’ve found my eyes veering toward the edges of the television set. While the task seems simple—“to sit or stand around the perimeter of the counter and monitor one specific line”—the preparation is intense. Understanding the patterns of each specific player helps to ensure no sight goes obscured. What’s even more fascinating is just as players advance through the tournament, so do line umpires. As Rothenberg writes, “By the final, the cream of the crop remains.” —Justin Alvarez

I was excited to see that the NYRB unlocked an essay, from 1985, by Umberto Eco on Krazy Kat and Peanuts. He’s good on the former, but on the latter, I found him to be inadvertently hilarious in his too-Freudian approach. He refers to Charlie Brown and the gang as “monster children,” distillations of modern industrial society’s neuroses. Poor Chuck is perhaps the most victimized: “This is why he is always on the brink of suicide or at least of nervous breakdown: because he seeks salvation through the routine formulas suggested to him by the society in which he lives (the art of making friends, culture in four easy lessons, the pursuit of happiness, how to make out with girls—he has been ruined, obviously, by Dr. Kinsey, Dale Carnegie, Erich Fromm, and Lin Yutang).” —N.R.

The Beauty of Code

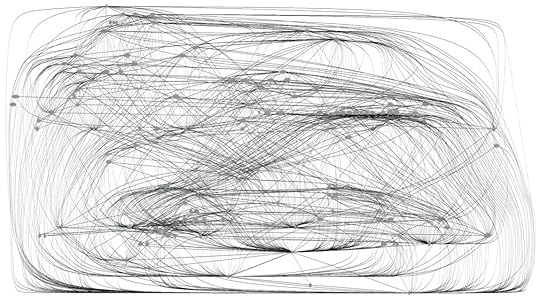

Dependency diagram (Image via TheDailyWTF)

This is what ugly code looks like. This is a dependency diagram—a graphic representation of interdependence or coupling (the black lines) between software components (the gray dots) within a program. A high degree of interdependence means that changing one component inside the program could lead to cascading changes in all the other connected components, and in turn to changes in their dependencies, and so on. Programs with this kind of structure are brittle, and hard to understand and fix. This dependency program was submitted anonymously to TheDailyWTF.com, where working programmers share “Curious Perversions in Information Technology” as they work. The exhibits at TheDailyWTF are often embodiments of stupidity, of miasmic dumbness perpetrated by the squadrons of sub-Mort programmers putting together the software that runs businesses across the globe. But, as often, high-flying “enterprise architects” and consultants put together systems that produce dependency diagrams that look like this renowned TheDailyWTF exhibit. A user commented, “I found something just like that blocking the drain once.”

If that knot of tangled hair provokes disgust, what kind of code garners admiration? In the anthology Beautiful Code, the contribution from the creator of the popular programming language Ruby, Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto, is an essay titled “Treating Code as an Essay.” Matz writes:

Judging the attributes of computer code is not simply a matter of aesthetics. Instead, computer programs are judged according to how well they execute their intended tasks. In other words, “beautiful code” is not an abstract virtue that exists independent of its programmers’ efforts. Rather, beautiful code is really meant to help the programmer be happy and productive. This is the metric I use to evaluate the beauty of a program.

He goes on to list the virtues of good code: brevity; reusability (“never write the same thing twice”); familiarity (Ruby is an “extremely conservative programming language” that does not use “innovative control structures” but “sticks to traditional control structures programmers are familiar with”); simplicity; flexibility (which Matz defines as “freedom from enforcement of tools,” so programmers aren’t forced to work in a certain way by the tools or languages they use); and, finally, balance: “No element by itself will ensure a beautiful program. When balanced together and kept in mind from the very beginning, each element will work harmoniously with the others to create beautiful code.”

So, beautiful code is lucid, it is easy to read and understand; its organization, its shape, its architecture reveals intent as much as its declarative syntax does. Each small part is coherent, singular in its purpose, and although all these small sections fit together like the pieces of a complex mosaic, they come apart easily when one element needs to be changed or replaced. All this leads to the happiness of the programmer, who must understand it, change it, extend it. This longing for architectural coherence leads to comparisons of code with music, which is often described as the most mathematical of the arts. There is, in fact, an anecdotal but fairly generalized belief among American programmers that there is a high correlation between coding and music-making, that many coders are musicians. A similar claim is made about mathematicians and music. These connections seem culturally encoded to me, specific to America—I’ve never heard of Indian programmers or mathematicians having a special affinity for music, apart from some being passionate listeners. Still, the code-and-music analogy is illuminating in that both practices prize harmonious pattern-making and abhor cacophony, a loss of clarity and structure. The snarl in the dependency diagram above may strike the civilian as a pretty picture, with its swirl of lines and punctuating sparks of gray; to the programmer, it is an abomination because it speaks of incoherence, incomprehensibility, unpredictability, sticky seams of connection that prevent swift diagnosis and make excision and replacement all but impossible.

With his emphasis on programmer happiness, Matz makes explicit his allegiance to Donald Knuth’s literate programming. He writes:

Programs share some attributes with essays. For essays, the most important question readers ask is, “What is it about?” For programs, the main question is, “What does it do?” In fact, the purpose should be sufficiently clear that neither question ever needs to be uttered … Both essays and lines of code are meant—before all else—to be read and understood by human beings.

The trouble of course is that as software programs grow bigger and more complex, the code they comprise tends to become unreadable and incomprehensible to human beings. Programmers like to point out that if each line of code, or even each logical statement (which may spread to more than one physical line), is understood to be a component, software systems are the most complicated things that humans have ever built: the Lucent 5ESS switch, used in telephone exchanges, derives its functionality from a hundred million lines of code; the 2008 Fedora 9 distribution of Linux comprises over two hundred million lines of code. No temple, no cathedral has ever contained as many moving parts. So if you’ve ever written code, you understand in your bones the truth of Donald Knuth’s assertion, “Software is hard. It’s harder than anything else I’ve ever had to do.” If you’ve ever written code, the fact that so much software works so much of the time can seem profoundly miraculous.

* * *

The International Obfuscated C Code Contest annually awards recognition to the writer of “the most Obscure/Obfuscated C program”— that is, to the person who can produce the most incomprehensible working code in the language C. The stated pedagogical aim of the contest is “to show the importance of programming style, in an ironic way.” But it has always seemed to me that confronting unfathomable code is the programming equivalent of staring at the abject, of slowing down to peer into the carnage of a car wreck. This is the reason that programmers expend time and effort in designing esoteric, purposely difficult computer languages like the infamous “brainfuck”—that really is its official name, with the lowercase b—which was created as an exercise in writing the smallest possible compiler (240 bytes) that could run on the Amiga operating system. “Hello, world!” in brainfuck is:

++++++++++[>+++++++>++++++++++>+++<<++.>+.+++++++ ..+++.>++.<.+++.------.--------.>+.

Brainfuck is a “Turing tarpit,” which is to say it is a very small language in which you can write any program that you could write in C or Java; but attempting to do so would, well, fuck your brain, and therefore the delectable frisson of terror the code above induces in discerning code cognoscenti. brainfuck is venerable and famous, but my favorite esoteric language is Malbolge, which was designed solely to be the most outrageously difficult language to program in. It is named, appropriately, after the eighth circle of hell in Dante’s Inferno, Malebolge (“Evil ditches,” reserved for frauds). In the language Malbolge, the result of any instruction depends on where it is located in memory, which effectively means that what specific code does changes with every run. Code and data are very hard to reuse, and the constructs to control program flow are almost nonexistent. Malbolge inverts the sacred commandments of literate programming, and is so impenetrable that it took two years after the language was first released for the first working program to appear, and that program was not written by a human, but generated by a computerized search program that examined the space of all possible Malbolge programs and winnowed out one possibility. “Hello, world!” in Malbolge is:

(==

And yet, this snippet doesn’t convey the true, titillating evil of Malbolge, which changes and quakes like quicksand. To contemplate Malbolge is to stare into the abyss in which machines speak their own tongues, indifferent to the human gaze; the programmer thereafter knows the pathos of her situation, and recognizes the costs of sacrilege. The coder’s quest is for functionality—“all computer programs are designed to accomplish some kind of task”—and the extension and maintenance of that functionality demands clarity and legibility. Illegibility, incomprehensibility—that way madness lies.

* * *

Programmers work doggedly toward correctness, but the sheer size and complexity of software ensures that bugs lurk within. A bug is, of course, a flaw or fault in a program that produces unexpected results. In 1986, the award-winning researcher and academic Jon Bentley published a book that is now widely regarded as a classic, Programming Pearls. One of the algorithms he implemented was for binary search, a method of finding a value in a sorted array, which was first published in 1946. In 2006, decades after the publication of Bentley’s book—by which time his particular implementation had been copied and used many thousands of times—one of his erstwhile students, Joshua Bloch, discovered that under certain conditions this technique could manifest a bug.16 Bloch published his finding under a justly panic-raising headline, “Extra, Extra—Read All About It: Nearly All Binary Searches and Mergesorts are Broken.” He wrote:

The general lesson that I take away from this bug is humility: It is hard to write even the smallest piece of code correctly, and our whole world runs on big, complex pieces of code.

Careful design is great. Testing is great. Formal methods are great. Code reviews are great. Static analysis is great. But none of these things alone are sufficient to eliminate bugs: They will always be with us. A bug can exist for half a century despite our best efforts to exterminate it.

That software algorithms are now running our whole world means that software faults or errors can send us down the wrong highway, injure or kill people, and cause disasters. Every programmer is familiar with the most infamous bugs: the French Ariane 5 rocket that went off course and self-destructed forty seconds after lift-off because of an error in converting between representations of number values; the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine that reacted to a combination of operator input and a “counter overflow by delivering doses of radiation a hundred times more intense than required, resulting in the agonizing deaths of five people and injuries to many others; the “Flash Crash” of 2010, when the Dow Jones suddenly plunged a thousand points and recovered just as suddenly, apparently as a result of automatic trading programs reacting to a single large trade.

These are the notorious bugs, but there are bugs in every piece of software that you use today. A professional “cyber warrior,” whose job it is to find and exploit bugs for the U.S. government, recently estimated that “most of the software written in the world has a bug every three to five lines of code.” These bugs may not kill you, but they cause your system to freeze, they corrupt your data, and they expose your computers to hackers. The next great hope for more stable, bug-free software is functional programming, which is actually the oldest paradigm in computing—it uses the algebraic techniques of function evaluation used by the creators of the first computers. In functional programming, all computation is expressed as the evaluation of expressions; the radical simplicity of thinking about programming as only giving input to functions that produce outputs promotes legibility and predictability. There is again the same fervent proselytizing about functional programming that I remember from the early days of OOP, the same conviction that this time we’ve discovered the magic key to the kingdom. Functional languages like Clojure conjure up the clean symmetries of mathematics, and hold forth the promise of escape from all the jugaadu workarounds that turn so much code into a gunky, biological-seeming mess. In general, though, programmers are now skeptical of the notion that there’s any silver bullet for complexity. The programmer and popular blogger Steve Yegge, in his foreword to a book called The Joy of Clojure, describes the language as a “minor miracle” and “an astoundingly high-quality language … the best I’ve ever seen,” but he also notes that it is “fashionable,” and that

our industry, the global programming community, is fashion- driven to a degree that would embarrass haute couture designers from New York to Paris ... Fashion dictates the programming languages people study in school, the languages employers hire for, the languages that get to be in books on shelves. A naive outsider might wonder if the quality of a language matters a little, just a teeny bit at least, but in the real world fashion trumps all.

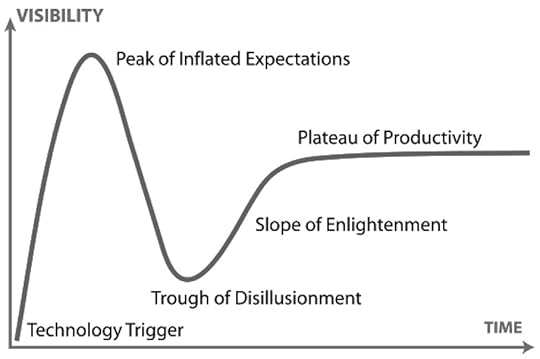

In respect to programming languages and techniques, the programming industry has now been through many cycles of faith and disillusionment, and many of its members have acquired a sharp, necessary cynicism. “Hype Cycle”—a phrase coined by the analysts at Gartner, Inc.—adroitly captures the up-and-down fortunes of many a tech fad.

Gartner, Inc.’s Hype Cycle (Jeremy Kemp, via Wikimedia Commons)

The tools and processes used to manage all this complexity en- gender another layer of complexity. All but the simplest programs must be written by teams of programmers, each working on a small portion of the system. Of course these people must be managed, housed, provided with equipment, but also their product—the code itself—must be distributed, shared, saved from overwriting or deletion, integrated, and tested.

Entire industries have grown around these necessities. Software tools for building software—particularly “Integrated Development Environments,” applications used to write applications—are some of the most complex programs being built today. They make the programmer’s job easier, but the programmer must learn how to use them, must educate herself in their idiosyncrasies and the workarounds for their faults. This is not a trivial task. For example, every programmer needs to use a revision control system to track changes and easily branch and merge versions of code. The best-regarded revision control system today is Git, created by Linus Torvalds (and named, incidentally, after his famous cantankerousness). Git’s interface is command-line driven and famously UNIX-y and complex, and for the newbie its inner workings are mysterious. In response to a blog post titled “Git Is Simpler Than You Think,” an irritated Reddit commenter remarked, “Yes, also a nuclear submarine is simpler than you think … once you learn how it works.” myself made three separate attempts to learn how Git worked, gave up, was frustrated enough by other revision control systems to return, and finally had to read a 265-page book to acquire enough competence to use the thing. Git is immensely powerful and nimble, and I enjoy using it, but maneuvering it felt—at least initially—like a life achievement of sorts.

You may have to use a dozen tools and websites to handle the various logistical aspects of software development, and soon the triumph starts to wear a little thin. Add another dozen software libraries and frameworks that you may use internally in your programs—again, each one comes bristling with its own eccentricities, bugs, and books—and weariness sets in. Each tool and preconstructed library solves a problem that you must otherwise solve yourself, but each solution is a separate body of knowledge you must maintain. A user named jdietrich wrote in a discussion on Hacker News:

My biggest gripe with modern programming is the sheer volume of arbitrary stuff I need to know. My current project has so far required me to know about Python, Django, Google App Engine and its datastore, XHTML, CSS, JQuery, Javascript, JSON, and a clutch of XML schema, APIs and the like …

Back in ye olden days, most programming tasks I performed felt quite natural and painless, just a quiet little chat between me and the compiler. Sometimes longwinded, sometimes repetitive, but I just sat and thought and typed and software happened. The work I do these days feels more like being a dogsbody at the tower of babel. I just don’t seem to feel fluent in anything much any more.

And every year, the new technologies arrive in a cloud of acronyms and cute names: MongoDB, HTML5, PaaS, CoffeeScript, TPL, Rx. One must keep up. On programmers.stackexchange.com, one hapless coder wrote:

I was humbled at a job interview yesterday almost to the point of a beat-down and realized that although I know what I know, my skills are pretty old and I’m getting to where I don’t know what I don’t know, which for a tech guy is a bad thing.

I don’t know if I can keep current just doing my day to day job, so I need to make sure I at least know what’s out there.

Are there well known blogs I should be keeping up with for software development?

The best—or at least the most ambitious—programmers read blogs and books, attend conferences to keep up with the state of the art, learn a new language every year or two. When you begin programming, one of the attractions is the certainty that you will never run out of things to learn. But after a few years of working in a corporate cubicle under exploitive managers, after one deadline too many, after family and age and a tiring body, learning the ins and outs of the latest library can feel like another desperate sprint on a nonstop treadmill. There is a reigning cult of overwork in the industry—the legend of the rock-star programmer usually has him coding sixteen hours a day, while simultaneously contributing to open-source projects, blogging, conferencing, and somehow managing to run a start-up—and this ideal has led many an aspirant to burnout, complete with techie thousand-yard-stare, clinical depression, outbursts of anger, and total disinterest in programming. This trough of disillusionment is so deep that for many, the only way to emerge from it is to leave the industry altogether, which rewards a few with fame and dazzling amounts of money, but treats the many as disposable cogs in its software production machine. The endless cycle of idea and action, endless invention, endless experiment, all this knowledge of motion takes its toll, leaves behind a trail of casualties.

The best—or at least the most ambitious—programmers read blogs and books, attend conferences to keep up with the state of the art, learn a new language every year or two. When you begin programming, one of the attractions is the certainty that you will never run out of things to learn. But after a few years of working in a corporate cubicle under exploitive managers, after one deadline too many, after family and age and a tiring body, learning the ins and outs of the latest library can feel like another desperate sprint on a nonstop treadmill. There is a reigning cult of overwork in the industry—the legend of the rock-star programmer usually has him coding sixteen hours a day, while simultaneously contributing to open-source projects, blogging, conferencing, and somehow managing to run a start-up—and this ideal has led many an aspirant to burnout, complete with techie thousand-yard-stare, clinical depression, outbursts of anger, and total disinterest in programming. This trough of disillusionment is so deep that for many, the only way to emerge from it is to leave the industry altogether, which rewards a few with fame and dazzling amounts of money, but treats the many as disposable cogs in its software production machine. The endless cycle of idea and action, endless invention, endless experiment, all this knowledge of motion takes its toll, leaves behind a trail of casualties.

This essay is an excerpt from Geek Sublime: The Beauty of Code, the Code of Beauty , © 2014 Vikram Chandra. Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press.

Vikram Chandra is the author of three highly acclaimed works of fiction, most recently Sacred Games, which won the Hutch Crossword Award for Fiction in 2006. Chandra lives in Oakland and teaches at the University of California, Berkeley.

Food for Thought

From the UK National Archives, 1939

When you’re traveling, you understand what you really need, or want, or find comforting—what you can do without and what’s essential. In my case, traveling illuminates an addiction to cookbooks.

People have written beautifully about their love of recipe reading. Laurie Colwin’s “Why I Love Cookbooks” is a classic explanation of the genre’s comforting appeal. Writing in The New Yorker, Adam Gopnik explains it differently:

A kind of primal scene of eating hovers over every cookbook, just as a primal scene of sex lurks behind every love story. In cooking, the primal scene, or substance, is salt, sugar, and fat held in maximum solution with starch; add protein as necessary, and finish with caffeine (coffee or chocolate) as desired. That’s what, suitably disguised in some decent dimension of dressup, we always end up making. We make béarnaise sauce by whisking a stick of melted butter into a couple of eggs, and, now that we no longer make béarnaise sauce, we make salsa verde by beating a cup of olive oil into a fistful of anchovies. The herbs change; the hope does not.

Whether the goal is comfort, aspiration, association, curiosity, research, it’s clear; people love to read cookbooks. Even Gwyneth Paltrow has claimed to be a bedtime cookbook-reader; of this, make what you will.

I have hundreds of cookbooks, and I love to read them. I especially enjoy reading about food while I eat, and keep a large stack of varied cookbooks on every surface where I might happen to set my plate. Some meals might call for Marcella Hazan, or Claudia Roden; other times you just want pretty pictures, or the American comforts of Lee Bailey. But all of this seems to me normal enough.

I began to be worried by this habit a few months ago. I decided to tidy my apartment before a houseguest’s arrival, and shelved all the many books I had lying around. For the first time in memory, my home was visibly cookbook-less; they were all tucked away in their boxes and cupboards in the kitchen. The sense of panic I experienced was visceral and immediate. I felt a real physical anxiety such as I have never known. Calm down! I told myself. They’re just under the counter! You can grab one the moment you want to—Edna Lewis or Nigel Slater or one of your old ones, or maybe some John Thorne, if you feel like essays! It’s okay!

And yet it didn’t feel right. I was upset, restless. I remembered something my mother had once said. For years, the sound track of my childhood was the slap of cards on the Formica kitchen tabletop as my mother played game after game of solitaire, from dawn to late and night. And then, one day, she stopped cold turkey. “Nothing done out of compulsion is healthy,” she said. I knew this to be true, and yet, I also remember the relief I felt when I pulled The Nantucket Open-House Cookbook off the shelf and laid it on the coffee table, telling myself with an addict’s dishonesty that it was just to get ideas for dinner.

As habits go, this one seems fairly harmless. But it’s also clear that the pleasures these other writers describe—that of vicarious gratification, and imagination—have morphed for me into something more. Simply put, I am not comfortable unless there are cookbooks around me, readily accessible. At the moment, I am in another country, beautiful and interesting, surrounded by good books. To stave off my rising anxiety, I have been surfing food websites and blogs. It will do, for the moment. And yet, I plan to run to the nearest bookstore as soon as possible and get a fix. It doesn’t need to be good. It doesn’t even need to be in English. That really isn’t the point.

Sunrise Solved, and Other News

Claude Monet, Impression, Soleil Levant.

Intellectuals and academics: step up your game! “Social docility, strong convictions of one’s personal impotence, infinite procrastination, plus, one surmises, the regular protestation that people must be able to get on with their proper job—their research and teaching—these excuses and tendencies prevent our noticing that the end of the world is nigh.”

Art historians have never settled the issue of when Monet’s Impression, Soleil Levant was painted. Now a physicist has used “astronomy, tide tables, weather reports, maps and historical photos to calculate the precise time.” If you’d guessed November 13, 1872, around 7:35 A.M., you’re right!

“How did we come to care so much about creativity? The language surrounding it, of unleashing, unlocking, awakening, developing, flowing, and so on, makes it sound like an organic and primordial part of ourselves which we must set free—something with which it’s natural to be preoccupied. But it wasn’t always so; people didn’t always care so much about, or even think in terms of, creativity.”

$$ GET PAID TO READ $$ A new grant “would allow writers to take three months’ leave to read the work of their fellow authors.”

“Gentlemen, this is no humbug”: how nitrous oxide, which began as a nineteenth-century recreational drug, became anesthesia.

September 4, 2014

You Are Quite Unnecessary, Young Man!

Antonin Artaud

The English translation of Roberto Bolaño’s excellent final novella, A Little Lumpen Novelita, is out this month. The book opens with an epigraph by Antonin Artaud, who was born today in 1896: “All writing is garbage. People who come out of nowhere to try to put into words any part of what goes on in their minds are pigs.”

Since I read it about a month ago, I’ve thought of this quotation every day, often as I’m writing—you can imagine the rat-a-tat of my keyboard punctuated with an occasional “All writing is garbage.” It’s a bracing sentiment, taunting and misanthropic, and a truer one than most of us would care to admit. At the moment, it flies in the face of our glad-handing literary culture, where every book is a good book and every writer in every MFA program partakes of a dignified struggle with Art.

Here’s how that quotation, which comes from Artaud’s The Nerve Meter (1925), goes on:

The whole literary scene is a pigpen, especially today. All those who have points of reference in their minds, I mean on a certain side of their heads, in well-localized areas of their brains, all those who are masters of their language, all those for whom words have meanings, all those for whom there exists higher levels of the soul and currents of thought, those who represent the spirit of the times, and who have named these currents of thought, I am thinking of their meticulous industry and of that mechanical creaking which their minds give off in all directions—are pigs.

Those for whom certain words have meaning, and certain modes of being, those who are so precise, those for whom emotions can be classified and who quibble over some point of their hilarious classifications, those who still believe in “terms,” those who discuss the ranking ideologies of the age, those whom women discuss so intelligently and the women themselves who speak so well and who discuss the currents of the age, those who still believe in an orientation of the mind, those who follow paths, who drop names, who recommend books—these are the worst pigs of all.

You are quite unnecessary, young man!

It’s vigorous spleen-venting, to say the least, and if by the end Artaud seems to have blunted the edge of his anger, we can still applaud his rigor. And we must, I think. The world needs its Artauds now more than ever. As Mark Leyner said in his Art of Fiction interview,

Bro, we’re living in the Kali Yuga, a Dark Age of petite bourgeoisie ideology, a petite bourgeoisie ideology whose resources and ruses are infinite and which ubiquitously permeates the world—high culture, low culture, bienpensant media, prestige literature, pop music, commerce, sports, academia, you name it. The only reasonable response to this situation is to maintain an implacable antipathy toward everything. Denounce everyone. Make war against yourself. Guillotine all groveling intellectuals. That said, I think it’s important to maintain a cheery disposition. This will hasten the restoration of Paradise. I’ve memorized this line from André Breton’s magnificent homage to Antonin Artaud—“I salute Antonin Artaud for his passionate, heroic negation of everything that causes us to be dead while alive.” Given the state of things, that’s what we need to be doing, all the time—negating everything that causes us to be dead while alive.

That’s what a line like “All writing is garbage” does for me: negates everything that causes us to be dead while alive. That quotation, too—from Breton’s “A Tribute to Antonin Artaud”—is worth some elaboration. Here’s the bit leading up to it:

Each time I happen to recall—nostalgically—the surrealist rebellion as expressed in its original purity and intransigence, it is the personality of Antonin Artaud that stands out in its dark magnificence, it is a certain intonation in his voice that injects specks of gold into his whispering voice. ... Antonin Artaud: I do not have to account in his stead for what he has experienced nor for what he has suffered. ... I know that Antonin Artaud saw, the way Rimbaud, as well as Novalis and Arnim before him, had spoken of seeing. It is of little consequence, ever since the publication of Aurelia, that what was seen this way does not coincide with what is objectively visible. The real tragedy is that the society to which we are less and less honored to belong persists in making it an inexpiable crime to have gone over to the other side of the looking glass. In the name of everything that is more than ever close to my heart, I cheer the return to freedom of Antonin Artaud in a world where freedom itself must be reinvented. Beyond all the mundane denials, I place all my faith in Antonin Artaud, that man of prodigies.

Visible Man

Richard Wright in a 1946 photograph by Carl Van Vechten.

Richard Wright was born on this day in 1908; he wrote Native Son and Black Boy, among dozens of other books, and his often controversial work helped to change race relations in the twentieth century. Wright hailed from North Carolina and in 1946 moved to Paris, where he befriended Sartre, Camus, and a number of expatriate writers, including Max Steele, one of The Paris Review’s founding editors. In our fiftieth anniversary issue, from 2003, the late Steele wrote “Richard Wright: The Visible Man,” a remembrance. Below is an excerpt from the essay.

I do not remember what month I saw him for the last time. He was strolling slowly in the light rain toward his flat on Monsieur Le Prince. He, in his double-breasted English raincoat and new beret, was walking upstream against the French with their umbrellas rushing down from the Comedie Française toward the Metro at Odéon.

I remember more vividly the first time I had met him at the Monaco (quite casually, even though I had arrived with a letter of introduction to him from our editor at Harper’s). When he learned I was from Chapel Hill he assumed immediately that I knew Paul Green, with whom he had written the play Native Son. He said, “The sleepiest man I ever saw.” He laughed and talked and laughed that laugh which he later admitted was his first line of defense, though it felt that afternoon like offense. He claimed that Green would go to sleep when they were writing dialogue for the most exciting moments in the play. “I’d say a line and look over and there Paul would be asleep.”

Five years later when I was again in Chapel Hill, teaching, I met Hugh Wilson, a cousin of Paul Green’s, who told me how exciting and dangerous those weeks were when Wright was in town working with Green on the play. “Of course he couldn’t stay at the Carolina Inn and there was no other place, so we got him a room down on Cameron Avenue in that big Victorian house behind those two giant magnolias. When the Ku Klux got wind he was there in a white neighborhood, they put out word they were going to kill him. Wright never knew that. Night after night Paul and I walked shotgun on that block. Paul would go up Ransom and I’d go down Cameron for a block or so and then we’d walk back and stand on the corner awhile, then patrol again. All night. I don’t know how Paul could write the next day. I didn’t care for Native Son. But Black Boy, that was one helluva book!” We admitted it had changed Wilson’s attitude and mine.

I heard later that Ellen [Wright’s wife] had placed a copy of Black Boy on Wright’s chest before the coffin was closed.

Dovlatov’s Way

This weekend, an intersection in Queens will be renamed Sergei Dovlatov Way.

Sergei Dovlatov

Sergei Dovlatov gave me a pistol when I was a child. It was just an air gun, it turned out, but my mother couldn’t tell the difference, and she was justifiably horrified to see me running around with a semiautomatic. It did not have a red plastic tip and it was nicely chromed, from somewhere in Eastern Europe. With enough pressure pumped into it, its little steel pellets could really hurt someone. Dovlatov found this very funny. Now we New Yorkers are naming a street after him.

And I’m thrilled. That street in Forest Hills, Queens, is the same one where his widow lives; it’s where his daughter, who recently translated Dovlatov’s great novel Pushkin Hills, grew up; and it’s where I grew up, too. At least eighteen thousand people share in my enthusiasm—that’s the number of petitioners it took to make this happen. That it’s such a formidable number should come as no surprise. Even if Joseph Brodsky was the greatest member of the so-called Third Wave of Russian immigrants—he won the Nobel and married an Italian woman—it’s Dovlatov whom readers love viscerally, unconditionally. How can we help it? When Matt Taibbi showed up to inaugurate Katherine Dovlatov’s translation a few months ago, I asked why he came: it was because Dovlatov was the one Russian author who made him laugh out loud. And suddenly we understood one another. Dovlatov made me laugh out loud, too, first in person, and then when I grew up, through his literature.

During the height of his fame, Dovlatov’s works were read universally. Solzhenitsyn, a dour man in his Vermont stronghold who wished to have nothing to do with the Third Wave “sausage immigrants,” read his entire three-volume collected works. The pieces translate easily because of their inherent humanity, and their humor, remarkably, translates as well. In Russia, where his work was retyped at night for samizdat, his secret readership grew, making many a fan. Half of Russia sat in jail, the other half stuck around to be with the first, and Dovlatov had been in both positions—and wrote about it, and still made it funny. The KGB, of course, was not a fan; they even destroyed typeset plates that had been prepared for publication. Dovlatov took the dissident-lite approach of simply not taking the Soviet Union seriously, and for this he was beloved.

When he emigrated he continued to write fiction, in addition to the newspaper he and my father were putting out, sometimes right from our living room. He worked on his prose with a perfectionist’s zeal. His writing reads as very light and sardonic, but I remember him saying that in a single sentence no two words should begin with the same letter. To us, he’s a modern classic—the Bulgakov who lived among us—but he also made the transmigration that every literary émigré hopes for. He became known in America, at least for a little bit. Everyone said he had “made it”: he’d been translated straight into The New Yorker only six months after he arrived. The KGB’s censors were his best publicists. He received a sweet letter from Kurt Vonnegut and saw five of his novels translated and published. (Pushkin Hills, the sixth, came out this year care of his daughter.)

On the street that will be named for him is the Russian store where he bought too much food when he wasn’t watching his weight, and the shop where he got his smokes when he wasn’t quitting. He lived there for twelve years. My memories of his home are dim because he spent so much time in mine, working on the immigrant newspaper that, were it to exist today, would probably be a blog. From his friendship with my father, I got to ride on the Goliath’s shoulders. Dovlatov would pick me up and hoist me as close to the ceiling as I’ll ever be. He was always the tallest man in the room, and I enjoyed being that high. My father appreciated the attention that the great writer gave his only son; my mother was terrified. And then he gave me that gun …

The idea that his very street might one day be named for him was unthinkable to us at the time—many of us were living hand to mouth. Dovlatov, like my father and all of his generation, lived an immigrant’s life and worked hard for his bread. And then he ate too much of it, drank too much, smoked too much, and died too young, in 1990.

The existence of a Dovlatov Street is a very New York thing to have, because the author took his characters, who always felt like heroes and not personages, right from his surroundings. He did it when he was working as a camp guard—ex-prisoners love him, despite this. He did it in the Soviet Union—eventually getting him expelled, though now he’s eternally in print. And he did it in Queens. The people who populate his American work are still around, many on the very street named for him.

Sergei Dovlatov Street is a great addition to New York City. I hope it will make tourists and residents alike Google the man, perhaps even read his work. And for immigrant Russians, it’s more than a memorial. Brodsky came away with the Nobel, but Dovlatov was “наш,” (pronounced “nosh,” meaning ours)—also the title of one of his greatest books. His street enshrines the entire Third Wave, the immigrants like Brodsky and my father, Alexander Genis, and the painters Komar and Melamid and Baryshnikov, and dissident heroes like Academic Sakharov and General Grigorenko, and even Yakov Smirnoff—the wave that I rode into life. Dovlatov Street means the Third Wave made it, that we were not mere “sausage immigrants.” Dovlatov deserves his street. I only hope that his widow isn’t too bothered by the pot-bellied men and the women in impossibly high stiletto heels, jostling for a photograph by the sign.

Daniel Genis is a writer working in Brooklyn. He’s been published in the New York Daily News, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Vice, and elsewhere. Follow him on Twitter @DanGenis.

The renaming ceremony for Sergei Dovlatov Way is this Sunday, September 7, at ten A.M., on 108th Street and 63rd Drive in Forest Hills, Queens. Dovlatov is the first Russian American writer to be honored with a street name in the U.S.

The City and the Pillar

The vaguely familiar sock monkey.

There are lots of interesting things to see right now at the New-York Historical Society: a delightful exhibit on Ludwig Bemelmans’s New York, a look at the role of cotton in the Northern war effort, a moving show called “ ‘I Live. Send Help.’ 100 Years of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.” All of these are worth seeing. None of them is what I want to discuss right now.

Swinging through the gift shop post-visit, my eye fell upon a sock monkey–making kit. This is not in itself so noteworthy; the gift shop contains an enticing selection of educational toys for young nerds, including a “My First Tatting” kit, a loom, and a mobcap. What was interesting, rather, was the image of the finished sock monkey displayed on the label. He looked vaguely familiar.

It took me a long time to realize the resemblance. It came to me hours later, in fact, when I was in the basement laundry room of my apartment building, cleaning the lint trap of the dryer:

“Nothing human is finally calculable; even to ourselves we are strange.”

―Gore Vidal

Pynchon Defends Homer, and Other News

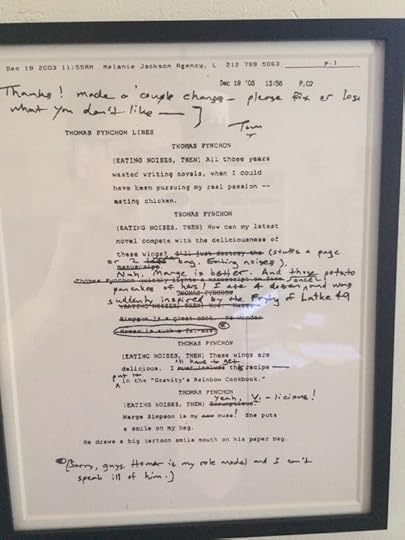

The Simpsons’s executive producer Matt Selman tweeted this script with Pynchon’s remarks.

Before he made his second “appearance” on The Simpsons in 2004, Thomas Pynchon made a few edits to the teleplay—he crossed out a pejorative line of dialogue about Homer’s ample posterior. “Homer is my role model,” he wrote in the margins, “and I can’t speak ill of him.”

Walter Benjamin’s “vexed relationship with academia”: “Benjamin could do first-paragraph seduction with a vengeance; yet on the several occasions when certain essays were the key to a prestigious university post—when those powers of seduction would really have worked in his favor—what does he do? He goes in the opposite direction, producing dense thickets of prickly, forbidding verbiage. Today, there isn’t a university press anywhere in the world that wouldn’t kill to get the rights to publish those same contentious, rejected essays.”

Now that so much of our media is stored in the Cloud, “the tide has turned against the collector of recordings, not to mention the collector of books: what was once known as building a library is now considered hoarding. One is expected to banish all clutter and consume culture in a gleaming, empty room.”

From If Only He Knew: A Valuable Guide to Knowing, Understanding, and Loving Your Wife , a 1988 Christian relationship guide that seems to presume marriage is a total bummer: “While a man needs little or no preparation for sex, a woman often needs hours of emotional and mental preparation … Comfort her when she is down emotionally. For instance, put your arms around her and silently hold her for a few seconds without lectures or putdowns.”

In which a Roald Dahl story moves a man to pursue beekeeping, a hobby that teaches us much about the nature of loyalty (and the loyalty of nature).

September 3, 2014

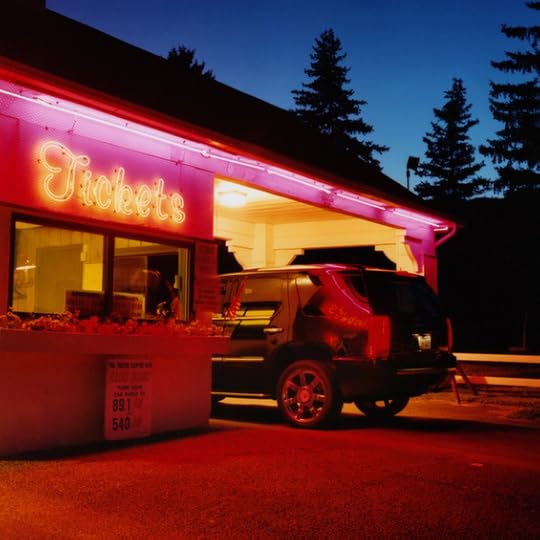

At the Drive-In

Dixon City, Pennsylvania. Photo: Stefanie Klavens

For her new series, “Vanishing Drive-ins,” the photographer Stefanie Klavens scoured the nation for extant drive-in theaters—there are fewer than four hundred now, she says, down from more than four thousand in the fifties—and photographed them with plenty of saturation and long exposure times. The result is a jarring (albeit beautiful) exercise in anachronism: late-model cars are swathed in the cheery neon of the fifties and sixties, suggesting a concept of Americana at once indelible and fleeting. Klavens explains the demise of the drive-in:

Over time, changing real-estate values began to have an effect on the drive-in. Land became too valuable for a summer-only business. Widespread adoption of daylight saving time in the mid-1960s subtracted an hour from outdoor evening screening time. The decline was further hastened by the advent of VCRs and home video rentals.

You can see more of her photos on Beautiful/Decay and at her website.

Malta, New York.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers