The Paris Review's Blog, page 670

August 25, 2014

A Library Without Books, and Other News

Florida Polytechnic University's new library is bookless. Photo: Rocket Science Photography / Florida Polytechnic University, via the Los Angeles Times

“We’d all like to believe in untranslatable words. It’s such a romantic thought: that there exist out there, like undiscovered desert islands, ideas we have never even conceived of…” Alas, it isn’t so. Ostensibly untranslatable terms like hyggelig (Danish) or saudade (Portuguese) have plenty of serviceable equivalents.

Today in the sad obsolescence of print (or, depending on whom you ask, the ineluctable march of progress): a new library with no books. At a center of higher education, no less.

And today in seemingly unobjectionable advice that’s actually terrible, vacuous, entitled, meaningless advice: “Do What You Love” is “the unofficial work mantra of our time … [a] secret handshake of the privileged and a worldview that disguises its elitism as noble self-betterment.”

On the literature of Alzheimer’s: “Because the full, internal experience of Alzheimer’s is an account that fiction alone can deliver, it’s no surprise that the go-to book for caretakers and early-stage sufferers is a novel.”

“For me, there’s a sure sign I’ll be able to muster the maturity to it takes to make art out of my life: When I’m finally able to laugh at a younger version of myself.”

August 22, 2014

Staff Picks: Moo, Maine, Malfeasance

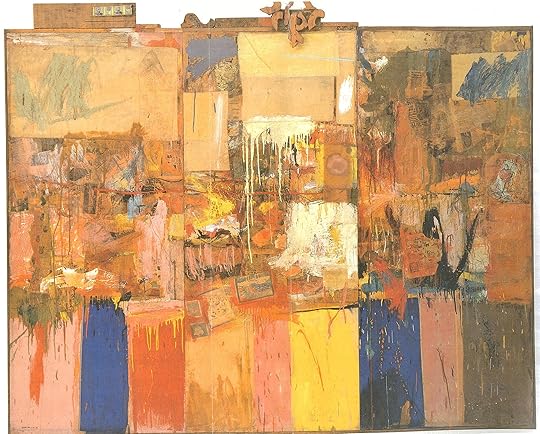

This collage helped solve a crime. Robert Rauschenberg, Collection, 1954-55; image via the New York Observer.

“From the outside it was clear that the building known generally as ‘Old Meats’ had eased under the hegemony of the horticulture department.” So begins Jane Smiley’s 1995 campus satire, Moo; from that first sentence I knew it was the only book I needed for the weekend. It had that tone—that late-century Midwestern tone. You hear it in Jonathan Franzen’s first two novels, and in Infinite Jest, too. It’s the sound of an omniscient narrator who is sophisticated and slightly wry and who, at the same time, belongs to a safe, stable, neighborly community, the sort of place where things can be “known generally.” Maybe because I grew up on the East Coast, in a city—or maybe just because it is so manifestly pre-Internet—that kind of sentence is as soothing and inviting to me as “Once upon a time.” And Moo lived up to its promise. —Lorin Stein

What happens when myth becomes reality? For the residents around Maine’s North Pond, a legend about a hermit became strikingly less legendary when the hermit, a man by the name of Christopher Knight, was found and arrested last year during a burglary attempt. For twenty-seven years, Knight had lived in the woods of Maine in a tent, never communicating with the outside world (except once, when he passed a hiker). “Silence is to me normal, comfortable,” he tells Mike Finkel, a journalist for GQ. “I’m not used to seeing people’s faces. There’s too much information there.” What’s remarkable about Knight’s story is that there wasn’t any particular reason he chose to disappear. He merely started driving one day and didn’t stop until he came across his camp in the woods. “I found a place where I was content.” Thoreau couldn’t have summed it up better himself. —Justin Alvarez

Sixty years ago in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the NYPD pinned a crime spree on four innocent men. What else is new, you might say. Well, a researcher has brought the malfeasance to light, and a collage by Robert Rauschenberg helped solve the mystery. Specifically, it was “Collection,” which Rauschenberg composed in the mid-fifties from newspapers containing accounts of the crimes. The Observer tells the story, which is full of crooked cops and falsified documents and botched autopsies and noirish goings-on under the Williamsburg Bridge; Rauschenberg’s involvement, however peripheral, makes the whole thing impressively surreal. —Dan Piepenbring

Many clichéd things can be said of the stories in Justin Taylor’s new collection, Flings. They’re hilarious and heartbreaking; there’s an existential loneliness to their characters; there’s a stark beauty in their sentences. But these sentiments smooth over the messy truths that Taylor works with—he’s managed to gather up all the confusion, repressed aggression, and misplaced acceptance of growing up in the nineties and becoming a young adult in the twenty-first century. Taylor isn’t afraid to place his characters squarely in our place and time. The narrator of “Sungold” manipulates his boss—a coked-up, alcoholic, trust-funded man-baby who owns an unnamed pizza chain—into not being so much of a fuck-up. In “Mike’s Song,” a brother and sister and their divorced father attend a Phish concert together. But behind his contemporary premises, Taylor is practicing a brand of acute, oblique realism that stretches back to Carver and Yates and even to Sherwood Anderson, in which events act as triggers for memories that are the real story. —Andrew Jimenez

It’s back-to-school time again, and there’s probably no more effective way to burden these precious last days of summer with anxiety dreams than to delve into a campus novel. And yet, I have no regrets about picking up Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, a classic about a young lecturer at a provincial English university who’s not too ambitious—he just wants not to be fired and also for this one girl to like him. Lucky Jim sends up the boredom and futility of midcentury academic pretension; the sour little cover illustration from Eric Hanson on the NYRB Classics edition is a nice bonus. In a characteristically witty passage, Amis unpacks the doublespeak of the phrase “Can I have a word with you?” among colleagues: “This was the most dreadful of all summonses … Intellectually, Dixon could conceive of such a request leading to praise for work done on indexing Welch’s notes for his book, to the offer of a staff post on Medium Aevum, to an invitation to an indecent house party, but emotionally and physically he was half-throttled by the certainty of nastiness.” —Chantal McStay

The popularity of the ironic urban musical has soared since its conception around the 1960s. Smash hits such as Guys and Dolls and Chicago, plus more recent shows like Hedwig and the Angry Inch and Urinetown, have all deconstructed the traditional sincerity that characterized musical theater at the beginning of the twentieth century. But how do we look back at the simplistic and silly musicals that we used to know and love? “I’m not ironic, I’m not very urban. I love trees. I hope I’ll never stop loving them. Trees, green meadows … who cannot love them?” That’s Oscar Hammerstein II defending the sentimentality of his lyrics with a Maria Von Trapp–esque list of his favorite things. When Hammerstein died fifty-four years ago this month, Times Square and London’s West End both went dark in tribute; the glitz and glamour of musical theater today provide the perfect backdrop for an ironic reaction, but keep them off and we see that, in Hammerstein’s words, “the things we’re sentimental about are the fundamental things in life.” Love, death, conflict … trees. —Helena Sutcliffe

So Vivid You Can’t Get Free of Them

Ray Bradbury

Do you know why teachers use me? Because I speak in tongues. I write metaphors. Every one of my stories is a metaphor you can remember. The great religions are all metaphor. We appreciate things like Daniel and the lion’s den, and the Tower of Babel. People remember these metaphors because they are so vivid you can’t get free of them and that’s what kids like in school. They read about rocket ships and encounters in space, tales of dinosaurs. All my life I’ve been running through the fields and picking up bright objects. I turn one over and say, Yeah, there’s a story.

—Ray Bradbury, the Art of Fiction No. 203, 2010

Ray Bradbury would be ninety-four today—for more on his Art of Fiction interview, be sure to read “Fact-checking Ray Bradbury,” by our own Stephen Andrew Hiltner. And for proof of Bradbury’s metaphorical gifts, check out “All Summer in a Day,” a 1954 story published in the commonsensically named The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It’s conceptually unforgettable and, among the stories of his I’ve read, uniquely haunting.

“All Summer” takes place in a school on Venus, or rather, the Venus of the future—humans have colonized the planet. Problem is, Venus is rainy. All the time. “A thousand forests had been crushed under the rain and grown up a thousand times to be crushed again.” The sun shines for only two hours (consecutive, fortunately) every seven years. And in this drenched Venusian schoolhouse, where all the descendants of the rocket men and women presumably suffer from constant Seasonal Affective Disorder and severe vitamin D deficiencies, there’s one girl, Margot, who remembers the glories of sunshine:

The biggest crime of all was that she had come here only five years ago from Earth, and she remembered the sun and the way the sun was and the sky was when she was four in Ohio. And they, they had been on Venus all their lives, and they had been only two years old when last the sun came out and had long since forgotten the color and heat of it and the way it really was.

Today, it so happens, is the day the sun will come out, and Margot is looking forward to it more than anyone. But when the teacher’s out, her classmates lock her in a closet, and as the rain begins to cease they forget all about her:

It was as if, in the midst of a film concerning an avalanche, a tornado, a hurricane, a volcanic eruption, something had, first, gone wrong with the sound apparatus, thus muffling and finally cutting off all noise, all of the blasts and repercussions and thunders, and then, second, ripped the film from the projector and inserted in its place a beautiful tropical slide which did not move or tremor. The world ground to a standstill. The silence was so immense and unbelievable that you felt your ears had been stuffed or you had lost your hearing altogether. The children put their hands to their ears. They stood apart. The door slid back and the smell of the silent, waiting world came in to them. The sun came out. It was the color of flaming bronze and it was very large. And the sky around it was a blazing blue tile color. And the jungle burned with sunlight as the children, released from their spell, rushed out, yelling into the springtime.

Margot isn’t among them, of course, and only later, after the rain has started again, do her ebullient classmates remember that they’ve trapped her in the closet. They let her out: the end.

As a parable about senseless cruelty, it sticks in the mind whether the mind wants it there or not. Junot Díaz referenced “All Summer” in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao: “Sucks a lot to be left out of adolescence, sort of like getting locked in the closet on Venus when the sun appears for the first time in 100 years.” (You could argue that it influenced R. Kelly, too, though you’d have your work cut out for you.)

Fresh Hell

Dorothy Parker

If you wish to celebrate Dorothy Parker’s birthday with a small gift to yourself, you have many options. An Etsy search of the writer’s name will give you letterpress prints and pillows and pins; a locket; earrings, several flasks; a bracelet; a range of portraits, including a cat in a cloche; a sampler; and a choice of two dolls. And the tote bags! Ah, the tote bags. Need I even mention the tote bags? I am not immune; yesterday, I treated myself to a Dorothy Parker cocktail, made with Dorothy Parker gin. At the Algonquin, no less. (There is also a certain charm to “what fresh hell” spelled out in Morse Code.)

Dorothy Parker’s Art of Fiction interview, from 1956, has always been among my favorites. She has no interest in glamorizing her reputation. She has scant regard for her much-vaunted wit. From the interview’s introduction: “Readers of this interview ... will find that Mrs. Parker had only contempt for the eager reception accorded her wit.” “Why, it got so bad,” she had said bitterly, “that they began to laugh before I opened my mouth.” I can’t think of an interview more honest, or more generous. She refuses to call herself a serious writer, saying:

There’s a hell of a distance between wisecracking and wit. Wit has truth in it; wisecracking is simply calisthenics with words. I didn’t mind so much when they were good, but for a long time anything that was called a crack was attributed to me—and then they got the shaggy dogs.

And on the vaunted Round Table: “I wasn’t there very often—it cost too much. Others went. Kaufman was there. I guess he was sort of funny.”

Say what she will, no one can take away from the body of her quotables—or, for that matter, an easy cultural shorthand that reduces her to bons mots. But for my money, there’s no quote that sticks with you quite so much as the final lines of that interview:

It’s not the tragedies that kill us, it’s the messes. I can’t stand messes. I’m not being a smartcracker. You know I’m not when you meet me—don’t you, honey?

Ask Questions Later

At the worst possible moment, Battlefield Hardline valorizes police violence.

An early screenshot of Battlefield Hardline.

The Battlefield series, one of the past decade’s most popular video-game franchises, has already given gamers the chance to play as soldiers in World War II, Vietnam, and the Middle East. Now Battlefield Hardline, slated for release early next year, allows players to assume the role of a new kind of soldier: the police officer. A recent preview of the game shows a cop throwing a thief to the ground and cuffing him; the player is given the option to Hold E to Interrogate. The officer yells, “Tell me what you know!” and earns fifty points: Interrogation successful.

To Visceral Games, who developed Battlefield Hardline, the roles of soldiers and cops are so interchangeable that Army camo can simply be “re-skinned” into police uniforms. In light of the killings, riots, fear, and unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, the game raises disquieting questions about the relationship between law enforcement and citizens—in short, it’s a horror to watch.

As a cop in Hardline, you’re tasked with preventing robberies and rescuing hostages, which often means shooting all the criminals until they’re dead. (The gentlest thing you can do is arrest them.) The game also enables players to take the role of the criminals, and perhaps the more troubling aspect of Hardline is that this experience is identical to playing as the police: both “the good guys” and “the bad guys” see the world through crosshairs. The best players shoot first, and shoot from behind.

“In multiplayer, the world is simple,” reads the game’s website. “You’re on one side of the law or the other.” This sort of tone-deafness permeates the game and its marketing. Given recent events, one might expect the hype around Battlefield Hardline to have gone quiet; instead, it’s becoming increasingly prevalent. On August 13, four days after police shot Michael Brown, Visceral Games released a twelve-minute trailer showing off a chunk of the game’s single-player campaign. The video opens as the main character—seemingly an undercover cop—is carted off by a guy in a bucket hat who points his pistol at your black partner and says, “Race is not a factor here. My dislike of you is strictly personal.” Even when Hardline is being self-aware, it’s tasteless.

Throughout the preview, a voice-over from the game’s creative director, Ian Milham, explains that you can complete levels one of two ways. The “stealth approach” allows you to sneak up on bad guys and arrest them. For each one you put in cuffs, you collect money—a bounty—that you can use to buy better weapons later. A less patient player can simply go in with guns blazing, shooting with impunity. Simply put: as a cop in Hardline, you have the choice of killing people or not. The decision is entirely dependent on your mood. The extent to which this varies from practice in the U.S., where police officers are ostensibly only permitted the use of deadly force as a last resort, is debatable.

I e-mailed Visceral Games to ask about the ethical predicaments that Hardline presents, but received no reply. When Hardline’s creators talk about the game, they do so with juvenile enthusiasm. Speaking to the video game site Polygon, Battlefield Hardline’s executive producer, Steve Papoutsis, explained that the inspiration for the game was all the “cool, kick-ass stuff” law enforcement has:

They’ve got cool motorcycles. And they’ve got helicopters. They even have police planes … And then like SWAT guys. Come on, who doesn’t like all the stuff SWAT guys load up in? They look pretty sweet.

Similarly, almost all of the writing about Hardline from video game outlets has shown blithe eagerness for the game’s urban setting. Polygon is perhaps the only major publication to criticize Hardline’s troubling themes, but even that comes after glowing preview articles with titles like “Is Battlefield Hardline the next eSports darling?”

If the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have shaken the country’s view of the military, if the rising number of school shootings has made us rethink our relationship to guns, none of these concerns have affected the robust sales of first-person shooters. In fact, as political and personal cognizance of violence has become more relevant, shooters have become more realistic, more violent, and more popular. The genre by itself has become a billion-dollar business, advancing by technological leaps and bounds each year.

Are first-person shooters popular because they’re in demand or only because they’re being developed? In an interview with NPR’s All Tech Considered about video game violence, Ken Levine, the creator of a sci-fi series called BioShock, explained that game publishers are more willing to fund shooters because they’re easy to market. “A shooter answers a lot of questions for you: the main mechanic is you have this gun, you have weapons, you have enemies, you have conflict coming at you,” he said.

The correlation between violence in entertainment and reality remains unclear at best, but it’s clear that games have an influence on American youth—it was just over a decade ago that the U.S. military developed America’s Army, a free online shooter that depicted ground warfare more accurately than comparable games. It was developed for seven and a half million dollars—just one-third of a percent of the Army’s annual marketing budget—and is considered one of the most successful recruiting efforts ever.

Last November, Maria Konnikova explored the reasons why first-person shooters are so popular in a piece for The New Yorker. “First-person shooters put our ability to control the environment, and our perception of our effectiveness, at the forefront of play,” she wrote. The irony that law enforcement appear to have neither control nor effectiveness in Ferguson appears to be lost on the 600,000 people who, as of this writing, have watched the Battlefield Hardline preview on YouTube since it was released.

Since 2002, when the Battlefield series was introduced, every major American conflict has been dramatized in an iteration of the game. Law enforcement seems like the natural next step. But it’s one thing to lionize the military; it’s another to advocate that the police is the military. The tragedies in Ferguson have renewed interest in the militarization of American law enforcement. As Jay Caspian Kang asked in The New Yorker last week, “Have we also become anesthetized to images of police in armored vehicles and full military gear?”

Battlefield Hardline implies that the answer is a resounding yes. The tagline on the game’s website reads, “Live out your fantasy of being a cop and criminal.” Note that conjunction: and, not or. In Hardline’s universe, the two aren’t mutually exclusive—perhaps the most subversive and intelligent point it’s likely to make.

Kevin Nguyen (@knguyen) is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York.

Mocha Dick, and Other News

Image: Creative Editions/Randall Enos, via the Atlantic

At the Morgan Library and in England, Jane Austen miscellanea abounds: recent years have seen the discovery, exhibition, and/or sale of Austen’s turquoise ring, Austen’s nephew’s memoirs (with her handwriting somewhere among the pages), Austen’s teenage notebooks, fragments of her unfinished novel, a stone shield excavated from a house near her birthplace …

“Once a sci-fi plot conceit, time travel has become among the most popular structural devices in contemporary fiction. Today ‘time machine fiction’ reigns supreme.”

Before Moby-Dick there was Mocha Dick—not a coffee-chocolate phallus but “a real-life whale … who fought off whalers for decades before being killed by harpoon.” It was a magazine story about Mocha that inspired Melville to write his novel; now, in a new illustrated book, Mocha Dick: The Legend and the Fury, the original whale gets his due.

The history of nine terms of endearment, including such perennials as sweetheart (1290) and sugar (1930), but also some deep cuts: mopsy (1582), bawcock (1601), and prawn (1895), the last of which ought to come into vogue again any minute now.

A manual for the first computer game—“The Ferranti Nimrod Digital Computer,” dubbed “Faster than Thought”—has sold for $4,200. The computer was designed specifically to play “a match-stick game called Nim that was played in the French movie L’Année Dernière à Marienbad.”

August 21, 2014

Robert Stone, Tabloid Writer

I think cultural undergrounds develop in the void left by the abdication of the official culture. During the sixties, so many august institutions seemed to have no self-confidence. The universities, corporations, the very fabric of the state. Everything you pushed just seemed to fall over. Everything was up for grabs. For me, the counterculture was like a party that spilled out into the world until one had the odd feeling in society that one was walking around looking at the results of a party that had ended a few years before—a big experiment. But there was no program, everybody wanted different things. I think Kesey wanted a cultural revolution, the nature of which was uncertain; he was just making it up as he went along. Other people were into political reform. Others thought the drugs would fix it all. Peace and love and dope.

—Robert Stone, the Art of Fiction No. 90

Happy birthday to Robert Stone, who turns seventy-seven today. Prime Green, his 2006 memoir, features more of his thoughts on the sixties—and he is very good, and often very funny, on the sixties. In the clip above, he reads an excerpt from the book about his time as a writer at a supermarket tabloid, an unsavory publication he calls the National Funder. Stone worked under a guy called Fat Lou “in the dank basement of hackdom,” at an office not far from the Flatiron Building. His forte: headlines. His compunctions: myriad. But his work as a yellow journalist: impeccable.

Recognition

From the poster to Art and Craft.

In The Recognitions, his brilliant novel about an art forger, William Gaddis wrote, “Originality is a device that untalented people use to impress other untalented people to protect themselves from talented people … Most original people are forced to devote all their time to plagiarizing. Their only difficulty is that if they have a spark of wit or wisdom themselves, they’re given no credit. The curse of cleverness.”

Art and Craft, a new documentary, is a similarly vexed study of authenticity and creativity: it tells the story of Mark Landis, an art forger who is, as the design site Colossal puts it,

arguably one of the most prolific art forgers in U.S. history, having tricked over sixty museums in twenty states into believing his masterfully created replicas are authentic artworks. The catch: so far, it appears Landis, who has been diagnosed as schizophrenic, has yet to commit a crime. While he’s caused headaches, confusion, and multi-year investigations, he has never sought to benefit or profit from his forgeries in any way. Instead, he enjoys the performative act of pretending to be a philanthropist who makes donations of obscure artwork to art institutions, many of which unknowingly exhibited the fakes, allowing Landis the secret thrill of seeing his work on display.

On the other end of the spectrum is Matthew Leininger, a righteous curator whom the Times calls “a kind of Javert to Mr. Landis’s Valjean.” Leininger has made it his mission to put a halt to Landis’s ruse; he “maintains a database of all known contacts with Mr. Landis, sightings of him and works he has copied … he uses a dry-erase marker to update a laminated map in his office.”

But has the man really done anything wrong—is he really a kind of failure? Certainly Gaddis would say so—“I tried to make clear,” he says of The Recognitions in his Art of Fiction interview, “that Wyatt [the forger] was the very height of a talent but not a genius—quite a different thing. Which is why he shrinks from going ahead in, say, works of originality. He shrinks from this and takes refuge in what is already there, which he can handle, manipulate. He can do quite perfect forgeries, because the parameters of perfection are already there.”

Maybe the same could be said of Landis, but that seems to give short shrift to his project. A 2012 article elaborates on the remarkable scope of his talents (or, if you remain skeptical of the validity of such things, his “talents”):

Landis creates works in oil, watercolor, pastels, chalk, ink and pencil, making most of his copies from museum or auction catalogs that provide dimensions and information on the originals.

He sometimes bestows gifts under different names, such as the Father Arthur Scott alias used at Hilliard. In that case, he told officials that his dead mother had left works including Curran’s oil-on-wood painting “Three Women” and that he was donating it in her memory … To convince museums he is a philanthropist, he also concocts elaborate stories about health concerns, said Cincinnati exhibit co-curator Matthew Leininger.

“He has been having heart surgery for almost thirty years,” Leininger said with a frustrated laugh. “This is the strangest case the museum realm has known in years.”

Landis, fifty-seven, acknowledges what he’s up to. He told The Associated Press in a phone interview from his home in Laurel, Miss., that he made his first forgery donation to a California museum in 1985.

“They were so nice. I just got used to that, and one thing led to another,” he said. “It never occurred to me that anyone would think it was wrong.”

There’s no release date for Art and Craft yet, but you can see the trailer, which brings to life Landis’s eccentricities, here. “The art world is a very strange place,” says one of its interviewees, in what may be the understatement of the year.

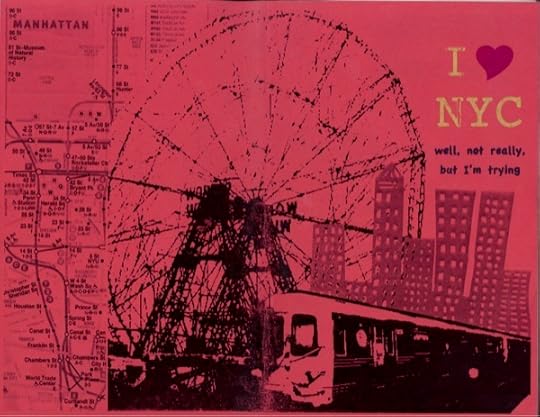

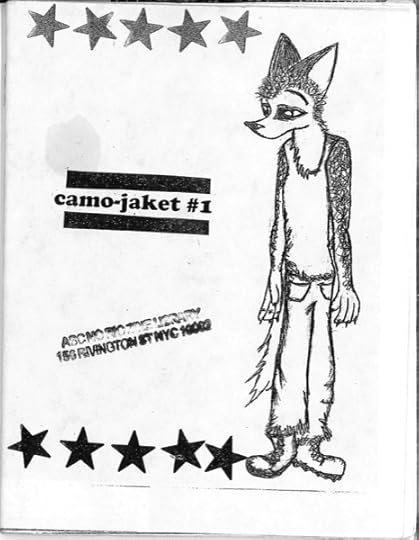

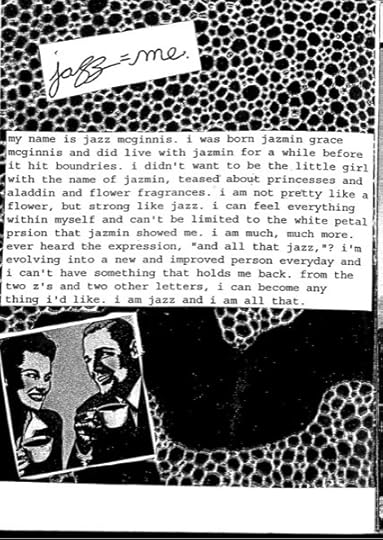

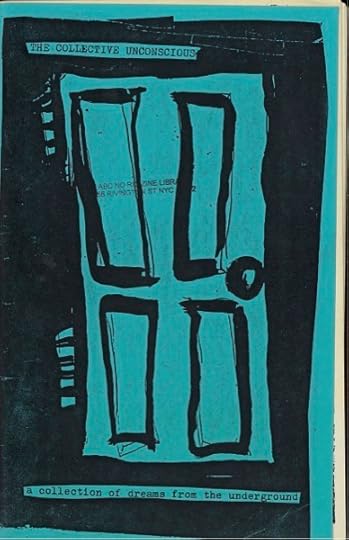

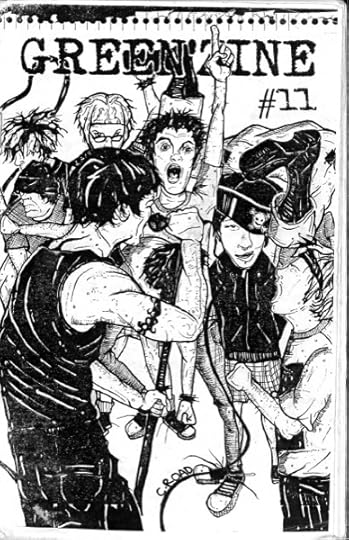

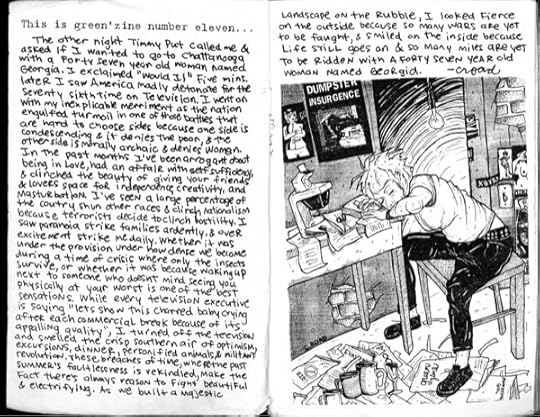

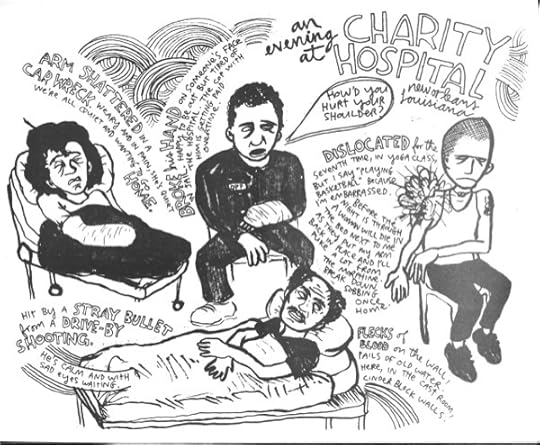

The Zines of ABC No Rio

“Zines + the World of ABC No Rio,” an exhibition on display through September 27 at the Center for Book Arts, draws from the extensive zine library at ABC No Rio, a social center founded on the Lower East Side in 1980.

ABC No Rio is maybe best known for its punk and hardcore collective—until recently, they hosted matinee punk shows on Saturday afternoons, and these were originally curated with the intent of avoiding the violence, racism, and homophobia that had come to dominant punk as it was practiced up the road at CBGB. But ABC No Rio was conceived as an art space; it has a darkroom, a silk-screening collective, and—no mean thing, back in the day—a computer lab.

The zines on display at the Center for Book Arts span more than two decades, and speak to the curious diversity of the medium, to say nothing of its endurance. As the Center explains:

By its straddling the line between functional brochure and works of art realized in book form, the zine has retained its popularity even as the internet has largely become the preferred method of self-publishing … [a zine] is usually a cheaply-made and priced publication, often in black and white, mass-produced via a photocopier, and bound with staples. The exhibit presents and explains a range of these self-same printed materials, mixing both artists’ original creations with items from the ABC No Rio zine library archives, covering subject matter from arts-community history to political commentary.

Above are fourteen highly various examples—between them, they feature stray bullets, quests for enlightenment, impromptu jaunts to Chattanooga, mosh pits, camo jackets, Aladdin, “dumpster insurgence,” and more.

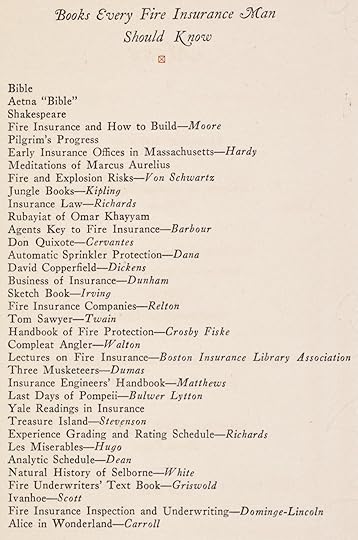

Presented (Almost) Without Comment

While browsing the New York Public Library’s menu archives—a fine way to pass a few hours—a friend of mine ran across this document, from a 1919 insurance pamphlet called “Why Read?”, and rightly supposed it would be of interest to me.

It feels like something out of Sinclair Lewis, but it’s both touching and instructive. I feel about it the way I do those signs in restaurant bathrooms. “All Employees Must Wash Hands,” they say. And I always want to add, “But really, everyone should.” Especially Lectures on Fire Insurance.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers