The Paris Review's Blog, page 671

August 21, 2014

The Limits of a Language, and Other News

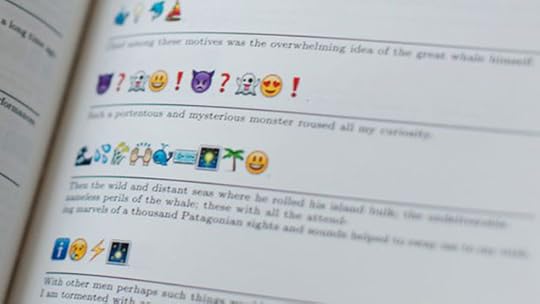

From Fred Benenson’s Emoji Dick.

“Could writers learn from carpenters? … Writers need to know more about the business of their art … During the days of postal submissions, writers often had to read ‘an issue or two of the publications to which they submitted, mainly due to the fact that that was largely how anyone knew about what journals were out there.’ Now writers unfamiliar with the submission process can sometimes produce ‘absurd results.’ ”

Stop. Look around you. Think. Are you in a Balzac novel? Some telltale signs: “There’s a woman you’d like to sleep with, so you decide to tell her an off-putting story about murder, castration, or bestiality … You play a lot of whist … You once tried to have sex with a panther.”

As a kind of language, emoji “are the social lubricant smoothing the rough edges of our digital lives: they underscore tone, introduce humor, and give us a quick way to bring personality into otherwise monochrome spaces.” But are they too conservative? “What habits of daily life do emoji promote, from the painted nails to the martini glasses? What behavior do they normalize? … In a broad sense, what emoji are trying to sell us, if not happiness, is a kind of quiescence … Emoji can represent cocktails, paparazzo attacks, and other trappings of Western consumer and celebrity culture with ease. More complicated matters? There’s no emoji for that.”

Oops. Now was not a good moment to release a feature film called Let’s Be Cops: “this is our only movie starring law enforcement run amok, at a moment when much of the nation is outraged that actual law enforcement is doing the same.”

When a programmer inserted the classic “Lorem Ipsum” placeholder text into Google Translate, he got some strange results. Cue the conspiracy theorists.

August 20, 2014

Dead Authors’ Homes

Salinger’s old house. Photo: Jim Mauchly / Mountain Graphics Photography

The literary real-estate market is booming. In May, Ray Bradbury’s house was for sale (Los Angeles, California; 2,500 square feet; $1.495 million). Then, in July, John Cheever’s house was for sale (Ossining, New York; 2,688 square feet; $525,000). At the time, you may have kicked yourself for failing to act on those—maybe you couldn’t scrape together the funds in time, or maybe you thought, Well, surely some other Dead Author’s Home will come along soon enough, and that will be the Dead Author’s Home for me.

You’re in luck: as reported by the Los Angeles Times, the Guardian, Page Six, and others, J. D. Salinger’s house is for sale, and it’s the most capacious authorial domicile yet (Cornish, New Hampshire; 2,900 square feet; $679,000).

The home’s current owner, Joan Littlefield, told the Valley News, a New Hampshire paper, that “she had been considering advertising the house, which she bought in the 1980s, in The New Yorker, in the hopes of attracting literary types.” To go by the coverage the property’s received, she has the right idea. But what does it mean to want to live in a dead writer’s house? When does fandom devolve into idolatry?

You might suppose that an ardent admirer of Salinger’s would have much to gain by inhabiting his private space—writerly inspiration, maybe, or a deeper connection to the work, or even just a constant, salubrious mental patter. (It’s another fine morning in J. D.’s kitchen, the satisfied homeowner thought.)

And why not? The fascination is valid. Pinning Salinger to a place humanizes him, and living in that place could be edifying. One can imagine him brooding in these rooms, writing and not writing and, most important, just sort of puttering around. He’s one of those revered authors whose work and solitude seems to have obscured his ordinary side, elevating him above the realm of human affairs. Intriguing, then, to have access to a space where he once trafficked in the same earthly minutiae as the rest of us, the junk mail and car insurance bills, the bottles of ibuprofen and dish soap, the mothballs and orthotic insoles.

But that’s about as far as it goes. No one knows if Salinger wrote anything in this house, and it’s been more than twenty years since he lived there; as the Valley News notes, it’s “filled with little cushions, crystal china, and fabrics in warm pinks and oranges.” Even if he’d been the most recent resident, to presume that some immutable, metaphysical trace of him remains amounts to superstition. What signs of life, really, does an author leave behind once his belongings are cast out, his property subjected to the real-estate rigmarole? We expect a ghost, the writer’s spectral feet shuffling through the bedroom, his august hand on our shoulders, urging us toward new creative heights. In reality, we’d be lucky to find a toenail clipping from the master, an errant stain in his carpet, a matted clump of his cat’s hair in the basement.

What you’re buying, then, isn’t privileged access: it’s only a set of jejune bragging rights. Imagine the dinner parties.

“Salinger lived in this house, you know.”

“No! Really? What did he work on here?”

“He hid, mainly. From the public eye.”

“Oh, well, I’m su—”

“Want to see the grout in the bathroom? It was his grout.”

That sounds ludicrous, but there’s truth in it. When the Littlefields moved into Salinger’s place, the Valley News says, they

came across various Salinger memorabilia, including old checkbooks, sections of fence, and, notably, his toilet, which made national news after a collectibles dealer tried to sell it on Ebay.

The Guardian adds,

The vendor asked $1m for the toilet, “uncleaned and in its original condition … Who knows how many of [his] stories were thought up and written while Salinger sat on this throne!”

This is the very worst impulse of fetishism, the same impulse that surrounds religious relics and autograph seekers and historic homes converted into stale, placarded museums. I’m reminded of a character in Richard Linklater’s Slacker who claims to possess Madonna’s Pap smear. “I know it’s kind of disgusting, but it’s, like, it’s sort of getting down to the real Madonna,” she says. That’s a reductio ad absurdum on what’s happening here: 2,900 expensive square feet ostensibly inflected with genius, imbued with the real Salinger. But every cupboard is empty, and the toilet’s been replaced.

Paranormal Activity

Fernand Lungren, Washington Square, 1897

James’s writings about New York disclose, more than anything, an anger, quite unlike any other anger in James, at what has been lost to him, what has been done, in the name of commerce and material progress, to a place he once knew. It is not an ordinary anger at the destruction of beauty and familiarity; it is much stranger and more complex than that, and it deserves a great deal of attention.

That’s from Colm Tóibín’s introduction to The New York Stories of Henry James. It’s a great primer on the writer’s hometown ambivalence—a quite explicable turn of events when one considers that any visit to the Village would have brought James face to face with the death of childhood, with constant overhaul, Mammon, and rampant sexuality on nearly every block. And with bad food, to boot.

On a constitutional in Washington Square Park today, my thoughts turned to James—they generally do, when I see the intact row houses fronting the park. (Well, James and NYU.) The man titled a novella after it—even if, as a friend recently pointed out, Washington Square gives less sense of the neighborhood than of interiority. (He’s said to have modeled the Sloper residence on memories of his grandmother’s. And if you want to see that brought to life, take a tour of the Merchant’s House Museum, one of the small treasures of the city, listed on any compendium of NYC’s haunted spaces.)

Perhaps my favorite of James’s New York stories is “The Jolly Corner.” Like The Turn of the Screw, it is a ghost story and more than that. It concerns a man returning to his empty childhood home, which is about to be subdivided into apartments.

It seemed to him he had waited an age for some stir of the great grim hush; the life of the town was itself under a spell—so unnaturally, up and down the whole prospect of known and rather ugly objects, the blankness and the silence lasted. Had they ever, he asked himself, the hard-faced houses, which had begun to look livid in the dim dawn, had they ever spoken so little to any need of his spirit? Great builded voids, great crowded stillnesses put on, often, in the heart of cities, for the small hours, a sort of sinister mask, and it was of this large collective negation that Brydon presently became conscious—all the more that the break of day was, almost incredibly, now at hand, proving to him what night he had made of it.

Now, that’s what I call psychological horror. And James would have known full well of Washington Square’s reputation for being haunted: its predevelopment history as a hanging yard filled with swinging bodies—and, before that, a Native American burial ground.

As I was walking down Washington Square North, I saw a large tour group pausing before one of the row houses. I thought, How fun! Were they on a literary or architectural tour of the area? Perhaps a ghost walk? I saw several pose for pictures; were they re-creating scenes from The Heiress, or the TV adaptation of Washington Square? Then I heard the tour guide:

“And this, of course, is the house from I Am Legend. I know you’ll all want pictures. I’m happy to take them for you.”

Deborah S. Pease, 1943–2014

A detail of the cover of The Paris Review’s Summer 1977 issue, which marked Deborah Pease’s first appearance in the magazine. Cover painting by William Copley, “Untitled,” 1977.

The Paris Review was saddened to learn that Deborah S. Pease—a poet, our former publisher, and a longtime supporter of the magazine—died in Boston earlier this week. She was seventy.

Pease was The Paris Review’s publisher from 1982 to 1992. She was a generous benefactor: in addition to her work with the Review, she supported Poets House and the Poetry Society of America, and she went on to help found A Public Space, whose editors write, “For her one of the truest ways to value art was to share it.”

An accomplished poet, Pease found a home for her work in the Review as early as 1977, and she returned to these pages often over the next decades; her work could be found in The New Yorker, AGNI, and Parnassus, among others, and in 1999 collected her poems in Another Ghost in the Doorway. She was precocious, too—a short story, “Doubt,” appeared in The New Yorker when she was only twenty-three, and her novel, Real Life, came not long afterward, in 1971.

Below is her poem “Self-Portrait in Iceland,” published in our Summer 2010 issue.

The face is featureless,

As though bound in tight gauze,

And therefore presents a mien

Of deadly restraint, and for a moment

It terrifies, this visage

Shorn of expression, the first impulse

Is to recoil from what appears

To be willful, if bloodless and unscarred,

Mutilation, but somehow

The set of the head, its angled tilt,

Imparts a liveliness to the sitter

That defies a nullity because it captures

Light from an unseen window

And reflects from an unseen radiance

A sanguine assertion of self

Drawn from tones of glacial tides

And roseate pumice stone.

The hands, extremities at rest

In the sitter’s lap just over the knees

And crossed at the wrists, are nearly convivial,

Inward-cupped, not articulated but nonetheless

Eloquent in their assured capacity

For labor, the lack of delicate modeling

Suggests a readiness

To take hold, to lend themselves

To tasks at hand, but the rudimentary

Aspect reveals no crudeness of character

In the sitter, no vulgarity, on the contrary

The hands are free from guile and coarse use,

They echo the face in elemental probity,

Holding in quick, almost offhand fashion

Gulps of sun,

Chunks of flame

In the shade of bleached volcanoes.

The Case of the Arabic Noirs

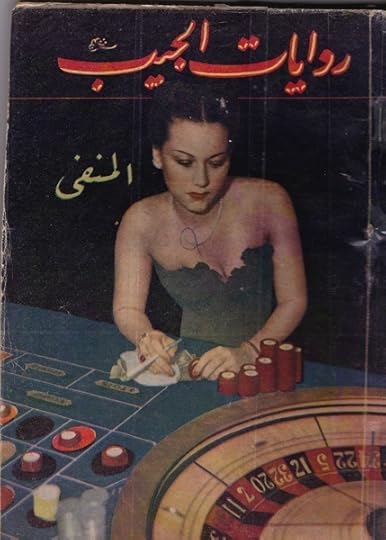

Pocket Novels: The Exile, J. Kessel, 1940.

“A Novel of Human Untruths, about a Russian woman and her princesses, in exile, from the pen of the great French writer J. Kissel,” presumably the French novelist and journalist Joseph Kessel (1898-1979).

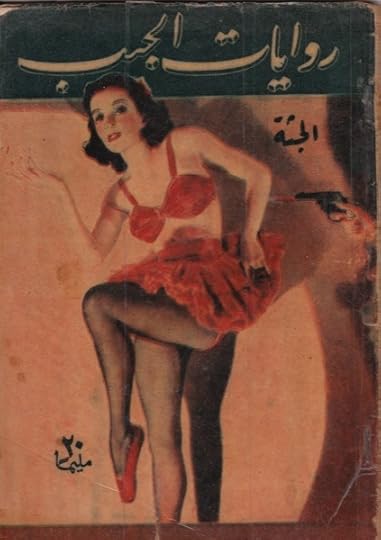

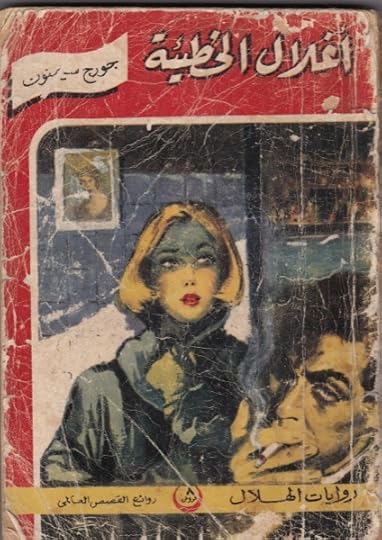

Pocket Novels: The Corpse, Georges Simenon, 1946.

“A quirky police tale,” according to the inside. Many popular fiction books were messily translated and repackaged, without bothering to credit the original text, author, or publisher. The artist of this cover, for instance, is not credited.

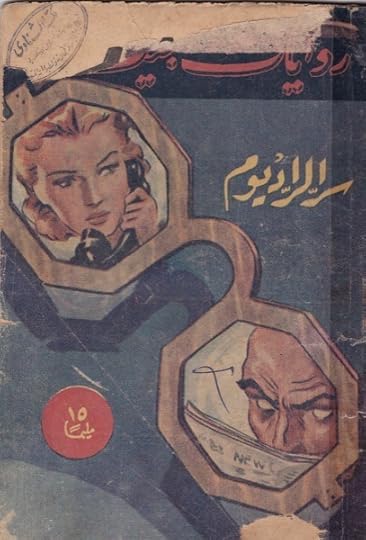

Pocket Novels: Secret of Radium, Albert Dewar Nashton, 1943.

“A police story of fantastic events written by the Briton, Albert Dewar Nashton.”

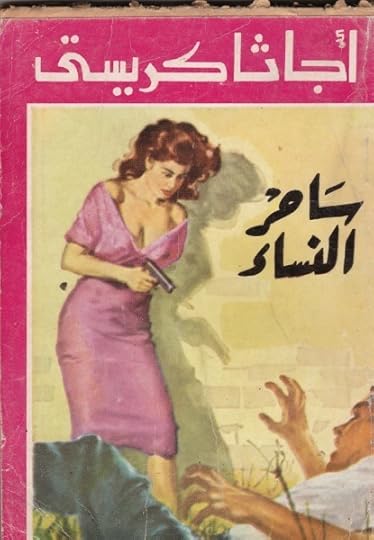

Charmer of Women, Agatha Christie, 1979 pocket book edition.

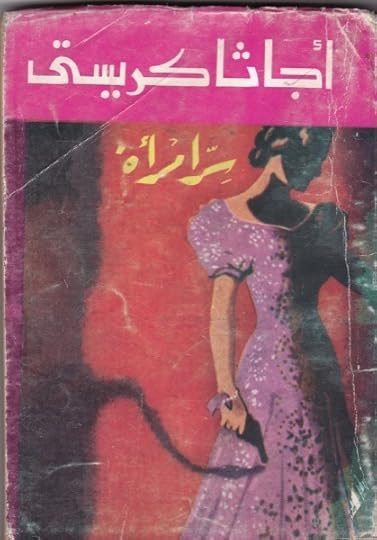

Mystery of a Woman, Agatha Christie, sold for thirty piasters, though undated.

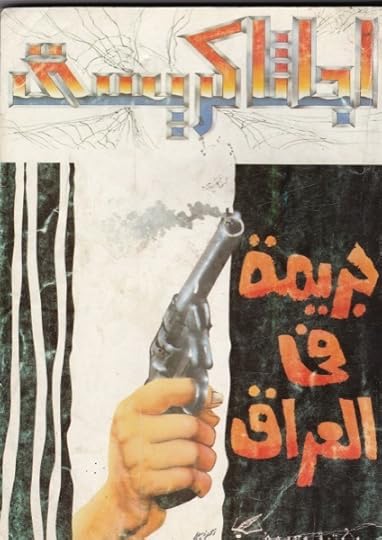

Crime in Iraq, Agatha Christie, undated. (Arabic version of Murder in Mesopotamia, with a different title).

Christie’s husband, an archaeologist, took her on digs across the Middle East and the scenes frequently appear in her prose.

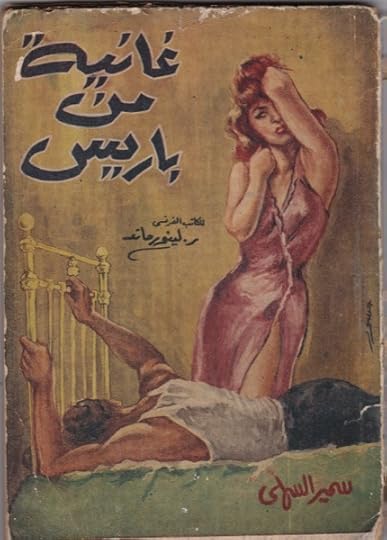

Floozy from Paris, R. Leonard (French), artist: Gasoor.

From the back cover: “In this book: The life of a French prostitute…” Undated; set in 1942.

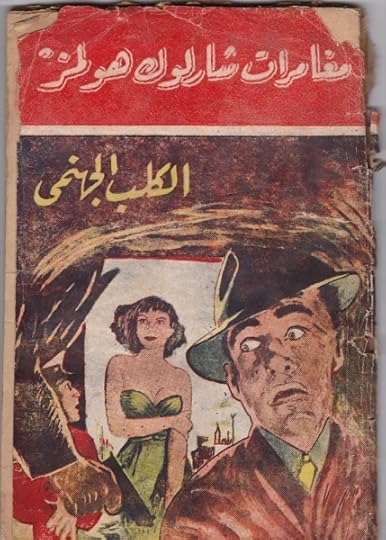

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Devilish Dog, undated.

A translation of The Hound of the Baskervilles.

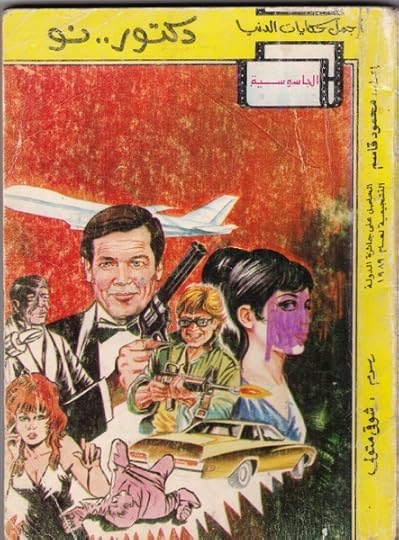

Dr. No: The Adventures of James Bond, drawings by Shawky Matooly, 1989.

Ian Fleming gets no acknowledgment in this pocket edition for young adults, complete with simple line drawings of action scenes.

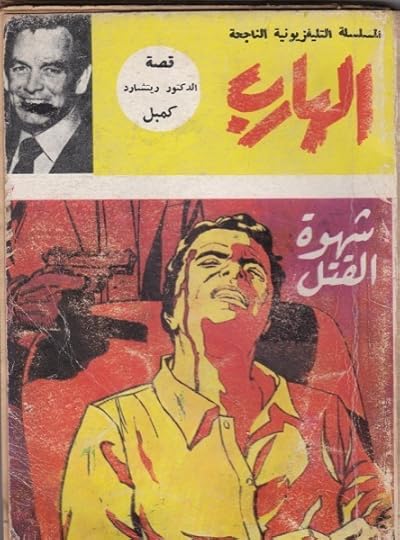

The Fugitive: Lust for Murder, Dr. Richard Campbell, undated.

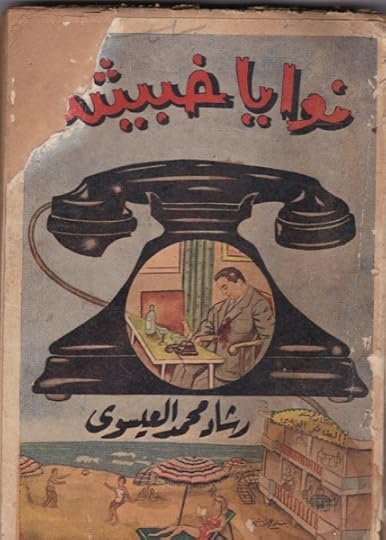

Malicious Intent, Rashad Mohamed El-Essawy, undated.

“Arabic stories from a new genre,” reads the inside cover.

The Shackles of Sin, Georges Simenon, 1959.

The backcover says the story is from the book, Four Days in a Lifetime, originally published in English in 1953.

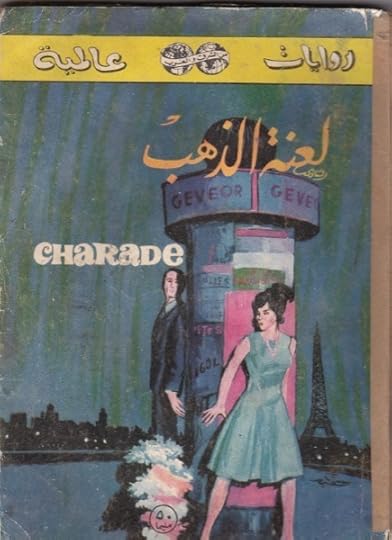

Charade, Peter Stone, #346 in imprint/series “Novels of the World,” undated.

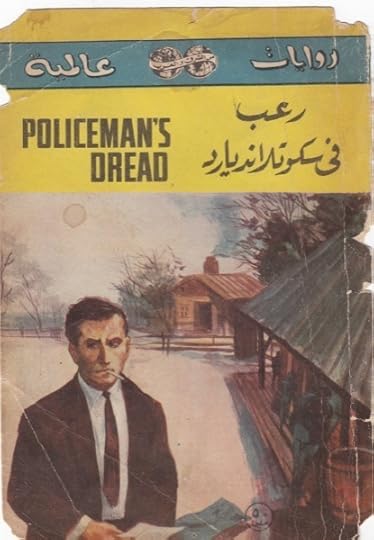

Policeman’s Dread, John Creasey, “Novels of the World” #399, undated.

Creasey (1908-1973) wrote some six hundred books under twenty-eight different noms de plume; at one stage he wrote thirty to forty books annually. There were hundreds of books from the “Novels of the World” series and myriad copies are gathering dust in Cairo archives and bookstands.

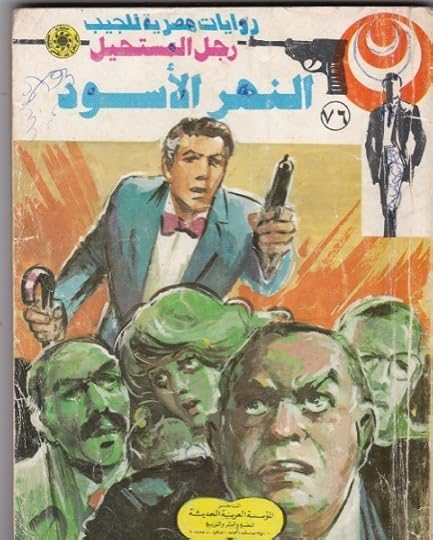

The Impossible Man: The Black River, Nabeel Farouk, undated, likely from the eighties.

Inside cover reads: “Police stories for youths, replete with sensational events.”

Cairo: the metal detector beeps. The security man wears a crisp white uniform. He nods and leans back in his chair. The lobby’s red oriental carpet, so worn it’s barely red, leads upstairs to the hotel tavern. Enter the glass doors, where a cat in a smart bow tie and vest reaches for a lonely bottle behind the bar. He takes his time; he’s been polishing glasses at the Windsor Hotel for thirty-eight years. Out the window, a motorcycle speeds through the dark alley. In 1893, this joint was ritzy—home to the royal baths, steps from the original Cairo Opera House. Tonight it’s dingy enough that Philip Marlowe might come here to tip a few back after clobbering some hoods. A fine joint in which to pore over pulp from the secondhand book market down the street.

It’s tempting to ponder the relevance of crime novels in contemporary Egypt. The 2011 revolution began on National Police Day as a revolt against the fuzz. When President Hosni Mubarak breezed off eighteen days later, the police dusted, too, leaving behind a Wild West. Gun sales skyrocketed, matched by holdups and carjackings. In the following two years, thugs ran Cairo’s streets. Ever since General Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi ousted former President Mohammed Morsi last summer, the coppers have been back in full force. White uniformed police operate checkpoints littered throughout the capital like discarded Coke cans. Cabbies are so scared that they’ve started wearing seat belts. And now, as authorities attempt to restore law and order, the crime genre is making a comeback.

Pulp emerged at the turn of the twentieth century. In the U.S., the twenties and thirties were the heyday of gumshoe thrillers, as Chandler and Hammett wrote detective stories for Black Mask. At the same time, Egyptian writers and translators produced thousands of unauthorized paperbacks, capped off with covers as lurid as their Western cousins’. In Cairo, each publishing house boasted hundreds of serials. Double Crime, for instance, a 1967 Arabic translation of the best-selling American novelist Norman Daniels, was number 420 in one publisher’s World Stories imprint. From Alfred Hitchcock and Charade to works of forgotten French and British novelists, anything and everything was translated into Arabic. The mass-market trend continued into the seventies, when sci-fi, Westerns, and spy novels began to outsell the tall tales of dizzying, melodramatic dames.

The golden age of illicit crime fiction translation—from the 1890s through the 1960s—corresponds to the construction of the Egyptian nation, from colonial rule and monarchy to President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization project. It’s the period when the Egyptian novel was canonized with stories of national consensus and the patriarchy: quite different than hotheaded genre fiction.

These translated thrillers captivated Egyptian readers in part because they shined a torch on the contested legal system of colonialism. The plots would be familiar to those who watch The Wire—inefficient courts, bumbling officers, the law’s futility in the face of crime. A classic example is Tawfik Al-Hakim’s Diary of a Country Prosecutor, a 1947 novel that’s part biographical, part hard-boiled, with a dash of bitters thrown in. The prosecutor waxes cynical about the legal institutions of British colonialism. In a satirical courthouse scene, Al-Hakim demonstrates the law’s worthlessness in the Nile Delta, where rural Egyptians are “required to submit to a modern legal system imported from abroad.” As in James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity, the law here can be fudged; the real disputes are settled outside of court.

“These novels form a tradition of legal muckraking,” writes Elliott Colla, chair of Georgetown’s Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies and the author of a new thriller, Baghdad Central. “Writing fiction about impolite or contentious social issues became an alternative way of addressing problems normally resolved through legal deliberation and action.” The stories of prosecutors and shamuses portrayed the ambiguity of law and order. All crime novels are political.

From the turn of the nineteenth century to the 1940s, Egyptian readers “had been accustomed to a steady stream of detective pulp fiction,” writes Colla. The remains of that vast canon are still strewn across the country. On a recent trip to Alexandria, I watched a hardened bookseller, a cigarette dangling from his lip, unload three grimy suitcases packed with English thrillers: The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Kiss-off, Casino Royale, House Dick, and dozens more. At the next stall, a table offered Arabic titles, with monikers like The Corpse, Floozy from Paris, Secret of Radium, and Lust for Murder. Each cover is more craven than the last: gun-slinging babes, gambling sexpots, smoking revolvers. The back covers offer red-hot teasers. “A police story of fantastic events … ” “The life of a French prostitute … ”

It’s too soon to speak of the Arabic noir’s resurgence, but there are clues. Ahmed Mourad’s 2007 novel Vertigo is a fine place to start. Mourad snapped photos for former President Hosni Mubarak; like Egyptian thriller writers of the forties, Mourad comes from an elite perch and knowingly comments on law and order in a lawless place, reviving tropes long beloved by Egyptian readers. (In reviewing Vertigo, one writer falsely called the thriller “a genre largely unknown in the Arab world.” He must not have visited Cairo’s book markets.) Vertigo begins in the rotating top-floor restaurant of the same name, situated in a posh Nile hotel. The protagonist, a down-and-out wedding photographer named Ahmed, sneaks a cigarette on the balcony as two heavyweights hold a private powwow at the bar. Suddenly, hatchet men break in and pump the goons with metal. The ensuing bloodbath leaves a pile of stiffs, including the house pianist, Ahmed’s best pal. This is a grimy look at the underbelly of Mubarak’s crony capitalism—the book is a best seller and has been translated to English.

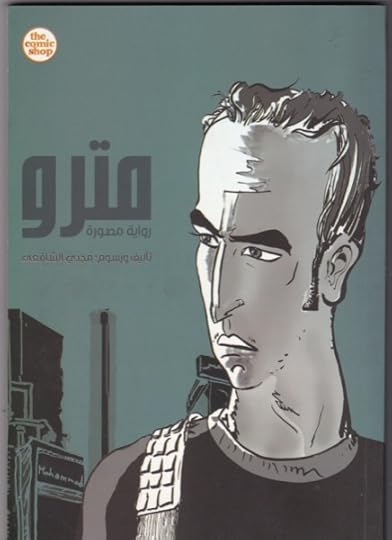

Metro: A Story of Cairo, Magdy El-Shafee, 2007. Third printing by the Comic Shop, Cairo, 2011.

Another modern-day equivalent of pulp is the graphic novel—an emerging medium that illustrates the divey corners that sleuths and skirts frequented a half century ago. Metro, by Magdy El-Shafee, is known as the original Arabic adult comic book, and it’s a kind of Cairo noir: on the first page, a beleaguered young computer programmer decides to rob a bank. When it was first published in 2007, Egyptian authorities seized all copies from the publisher, though the reason remains a mystery. Was it the narrator’s harsh antiregime attitude, his use of nudity and expletives, or the publisher’s activist reputation? The book was republished in Cairo after Hosni Mubarak took a fall, but it’s still hard to find in Arabic. (It’s on sale worldwide in translation.)

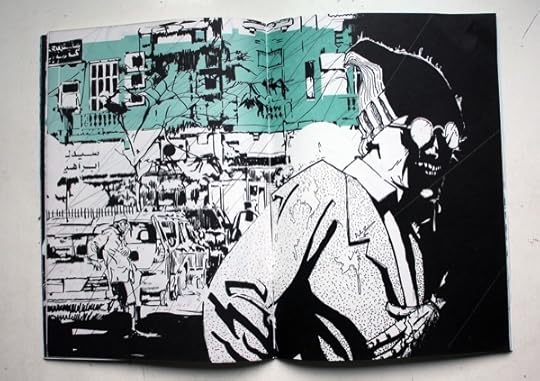

Whatever the reason for the comic’s censorship, its notoriety provoked other young artists to engage with noir aesthetics in telling contemporary stories of depravity. Ganzeer, the pseudonym of a thirty-two-year-old graphic artist whose art installations and graffiti are landmarks in Cairo and elsewhere, is inspired by Metro’s antihero. “Of course you could relate to someone opposing the government, opposing the police, more so than you can relate to this idea of a noble police officer who has to solve crimes for the greater good,” Ganzeer has said. This is the common thread between the new graphic novels and noirs of old: don’t trust the law.

In May, Ganzeer decided to skip town. A jingoistic Egyptian TV host put a finger on the artist. On live television, that gangster TV anchor disclosed Ganzeer’s real name and aired his photo, in retribution for antiregime graffiti. Ganzeer is now in New York, having drifted from one noir city to another.

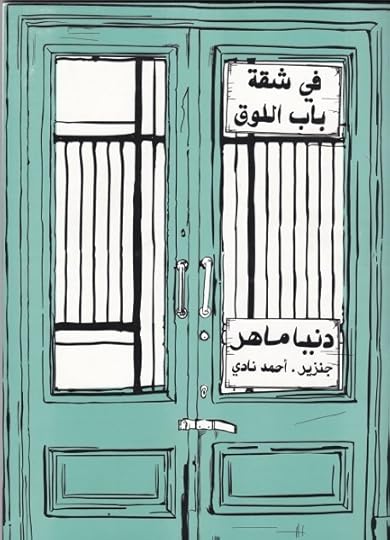

The Apartment in Bab El-Louk, by Donia Maher Ganzeer, Ahmed Nady, 2014.

Ganzeer’s latest publication is a hard-boiled graphic novella written by Donia Maher, a Cairo-based writer, entitled The Apartment in Bab El-Louk. Ganzeer elegantly laid out the text, the scattered rantings of an agoraphobic misanthrope, more poetry than prose—alongside images of the gritty downtown flat. You’re forced to listen to the anonymous narrator, screaming at unwanted visitors, neighbors and maids who knock on the door of the cramped apartment. Hitchcock might have conjured up such a neurotic character, a dark face peeping out the window at a quarrel on the street below. “You’ll be scared, even though you’ve locked the door,” says the narrator, speaking with brevity that portends doom.

The last eight pages of this “fabulous noir poem,” as its been called, feature a comic by Ahmed Nady. He’s an insurgent graffiti artist and illustrator of grotesque political caricature, the perfect guy to draw a shakedown at the hands of corrupt cops. In his comic, we learn that the reclusive narrator has been murdered. The cops bust into the joint. But they pinch a patsy, an innocent neighbor, rather than the real culprit.

“The cops are not the heroes in this story … That’s not the way things roll in Cairo. You don’t have an investigator; you don’t have a private eye, or whatever. You’re totally on your own,” Ganzeer said in April, in his Cairo studio, beside a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf of English and Arabic comics. He emphasized the pervasive antipolice violence that climaxed during January 2011 uprising: “People went and burned down every single police station.”

Detail from Ganzeer’s illustration.

From the Semiramis Hotel’s lobby, a two-minute waltz from Tahrir Square, Cairo itself seems like a dime novel. The Semiramis itself has been ransacked by toughs several times since the revolution, and last year, the hotel chefs brandished kitchen knifes to scare off troublemakers. Simply reading the newspaper stirs up familiar noir themes. Headlines provide grist for whole novels: “Egyptian police captain sentenced to death for murder-robbery.” Or “Egypt policeman killed defusing bomb near president palace.” And “Policeman shot dead while rescuing girl from kidnappers.” And last month, a new soap opera on police corruption was banned. In Cairo, it seems, life imitates pulp. Time to rent a room at the Windsor and start typing.

Jonathan Guyer is senior editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs . He blogs at Oum Cartoon and tweets @mideastXmidwest .

Joyce Recommends the Red, and Other News

“There is jollity.” (Jollity not pictured.)

Social media has warped the way we think of “sharing our stories,” but the status update hasn’t obviated the need for memoir. “I worry that we’re confusing the small, sorry details … for the work of memoir itself. I can’t tell you how many times people have thanked me for ‘sharing my story,’ as if the books I’ve written are not chiseled and honed out of the hard and unforgiving material of a life but, rather, have been dashed off … I haven’t unburdened myself, or softly and earnestly confessed. Quite the opposite.”

A bit of searing on-the-ground reporting from James Joyce’s birthday party, 1931: “The waiter brings a special wine which Joyce recommends to us very earnestly though he does not drink it himself as it is red. It is Clos Saint Patrice, 1920 … ‘He is the only saint whom a man can get drunk in honor of,’ Joyce says, praising Patrick in this way. We laugh, but he insists that this is high praise … In the apartment to which we return there is jollity. George Joyce sings; Sullivan sings; James Joyce sings.”

And while we’re on Joyce: “I started illustrating Finnegans Wake in 2009 because no one convinced me not to,” writes a man who has illustrated Finnegans Wake because no one told him not to.

The third novel in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series is out this month, and Ferrante—a pseudonym—has granted a rare interview. Is this why she guards her identity? “‘My desk mate, with whom I had a great friendship, suggested we write a novel together,’ she explains. Together, they came up with a story, and the friend wrote the first chapter. Ferrante didn’t like it, and so she wrote the entire story herself, from beginning to end, telling her friend she wasn’t up to the project.”

Don Pardo, the distinctive, stentorian announcer for Saturday Night Live, died this week; he got his start in game shows. “Staff announcer was such a prestigious job that members of the profession, in another holdover from radio, typically wore tuxedos while on the job, even though the audience hardly ever saw them and they were mainly confined to an ‘announce booth’ in or near the studio. Even simple station breaks—‘This is the National Broadcasting Company’—were done live from those close quarters.”

August 19, 2014

Frozen Peas

Orson Welles in F for Fake, 1973, three years after the Frozen Peas recording.

I watched two biopics this weekend. Both had been well reviewed, and both featured bravura lead performances from actors who played, in both cases, bona fide geniuses. You walked out of the movie knowing more about these geniuses’ careers, their achievements, their impact on the world. But both movies were a mess: filled with pacing issues and downward-spiral clichés. Which, I guess, makes a certain kind of sense. Most real lives have third-act problems.

There are exceptions, of course, both in life and in art—you don’t need me to enumerate the pleasures of Lawrence of Arabia. And I am all for a long life well lived. A cradle-to-grave biopic presents certain inevitable challenges, especially if your subject’s death is a peaceful one. And the clumsiness in such films is no crime; most of them don’t do much more than fall into well-trodden, safe paths; after the inevitable narcissistic degradation—the drug-fueled rages, the alienation of faithful retainers—we see the hero, more or less well aged by makeup, making amends, embracing, basking in former glories and the comforts of old age. Sometimes he sings.

But what would happen if, instead of the triumphant reunion, the bygones being bygones, we ended with something along the lines of a Frozen Peas commercial? I’m thinking of the infamous recording of an old, diminished Orson Welles caviling over the script for a 1970 British peas commercial by a company called Findus. It’s a short clip—a mere four or five minutes. But there’s more rage, tragedy, and pathos packed into it—more truth about a life—than in most of the baggy biopics of the last ten years combined.

DIRECTOR: Can you emphasize a bit “in”? “In July.”

WELLES: Why? That doesn't make any sense. Sorry. There's no known way of saying an English sentence in which you begin a sentence with “in” and emphasize it. Get me a jury and show me how you can say “in July” and I’ll go down on you. That’s just idiotic, if you'll forgive me by saying so … That’s just stupid. “In July”? I’d love to know how you emphasize “in” in “in July” ... Impossible! Meaningless!

Field of Dreams

Chasing down one grand slam.

From Baseball ABC, 1885

It was my 3,664th day on Earth, as I later calculated, and I was in a Little League fantasy scenario in Princeton, New Jersey. Play-offs, bases loaded, up at bat against an intimidating pitcher with a gnarly high kick. For an instant, my Louisville Slugger met with the ball, the leather and rubber shape-shifting against the aluminum. A roper up the middle into deep center—I can still feel the smack off the fat of the bat. I’d hit an inside-the-park grand slam. This was my finest moment as an athlete. It’s forever seared into my brain, scored by the cacophony of yelping mothers and fathers loud enough to drive kids away from the ice-cream truck to investigate.

This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Little League’s existence, culminating in August’s Little League Baseball World Series in South Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Williamsport’s Carl Stotz founded the league in 1939 by rounding up his nephews and their neighborhood friends. With the added attention to Little League this year, I began considering my brief moment of glory and how many children over the decades have received such a jolt of confidence—or the opposite—on ball fields nationwide.

The league has since ballooned into an international behemoth, with more than two-hundred thousand teams in all fifty states and more than eighty countries the world over, from Uganda to Kyrgyzstan. Each year now, more than two million boys (and some girls) play ball—their teams often sponsored by local businesses and larger corporations—and get schooled in triumph and failure, sometimes life and death. (The year 1956 marked the first on-field death in Garland, Texas, when Jerry Armstrong hit the twelve-year-old Richard “Rick” Oden in the head with a pitch.)

Our own conquests may not occur in front of the forty-five thousand live fans and more than a million TV viewers the Little League World Series attracts, but they mold our characters nonetheless, before modest collections of parents and siblings. Still, I realized how little detail I actually recalled from my big day. Who was the pitcher? What was the weather like? How old was I exactly?

These questions presented something of a dilemma. We all have seemingly trivial moments of youthful triumph—the buzzer-beating basket, the game-winning goal—that surface in our minds with undue frequency. In that way, nostalgia can be depressing. We glorify a past that’s now unattainable, and that preservation seems to value it over future accomplishments. So, yes, I wanted to investigate my crowning athletic achievement. Just as much, though, I wanted to discover why I cared.

* * *

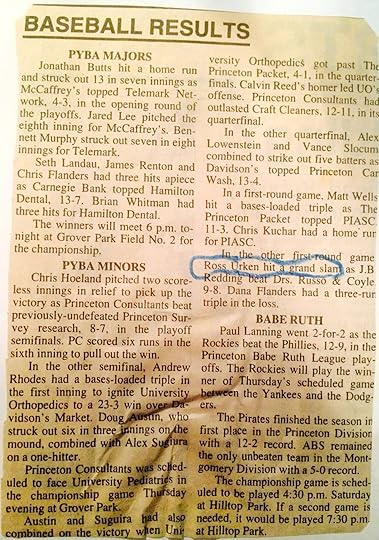

Exhibit A: The Princeton Packet

Princeton in springtime is a baseball fantasyland. The dogwoods and the white buds of the Bradford pears on Witherspoon Street always reminded me of the snowy landscape of Super Mario Bros. World Six on old-school Nintendo. As the baseball season moves deeper into summer, the whole town is drenched in a deep Crayola green.

In a scrapbook, I found a clipping from the Princeton Packet confirming that my grand slam, the apex of my sports career, was not entirely imagined. But the date was missing; I’d squared off the four corners of the yellowed scrap.

So I contacted a research librarian at the Princeton Public Library, which has the Packet archives on microfiche, and within twenty-four hours, boom: a PDF copy of the Friday, June 21, 1996 edition popped into my inbox. Given that play-off competition took place on Saturdays, my game would have been the previous weekend, June 15, 1996. I would have just turned ten, making me 4’9” and seventy-eight pounds. But that pitcher …

I tracked down Dana Flanders, a player from the opposing side mentioned in the article, on Facebook and politely interrogated him. He shot me back a message saying he only lived in town for two years and didn’t recall the game in the slightest. These memories are fragile. The crowd, in my mind, comes in splotches of color, as in a LeRoy Neiman painting.

Next I tried my father, the alliteratively named Irvin Urken. For him, the slam was confirmation of his advantaged gene pool. He’d have to remember the pitcher.

“I know who it was—the guy with the really high kick … ” he said. He paused searchingly. My father in those days ran the local hardware store, and though he knows faces, he can’t readily access names.

So we triangulated information, starting with the company of the pitcher’s father. A few minutes poking around the Internet, and voilà: it was Jonathan Lauri. For more intel, I contacted my teammate and lifelong friend Eli Obus.

“I remember Lauri’s kick was something like a less extreme version of El Duque,” he wrote, referring to Orlando Hernández Pedroso, the former Yankee pitcher who burst onto the scene two years after the Lauri incident.

I texted my friend Will Barrett, who recalled my grand slam and described Lauri as a power pitcher, like a Roger Clemens. And then, the embers of my memory stoked, I recalled that Henry Kerins, who now lives in Beijing, was on Lauri’s team.

“He had a very high and slow windup, and his leg would extend and slide through the sand on the mound as he released,” Kerins wrote. Also on the team with Kerins was Charles Mostoller, who told me he played catcher for Lauri’s “very hard but wild pitch.” Mostoller, in turn, sent me to Simon Landau, another catcher for Lauri. This is the midnineties, and we’re trying to have a synapse fire.

“Too bad we didn’t have smartphones and YouTube then,” Landau wrote. “Your slam could have lived forever.”

At last, I friended Lauri on Facebook. He’s now a lawyer in Central Jersey.

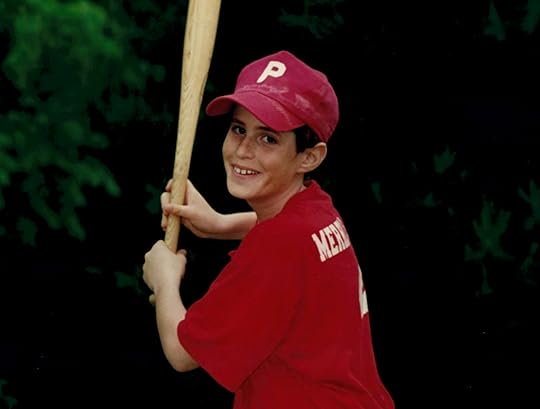

The author in his prime.

“I unfortunately have zero memory of that game,” he wrote. “I wish I did. Maybe the only way my brain could cope with a grand slam was to black it out lol. I wish we still had these memories.”

But what was the origin of that epic kick?

“I remember being taught that a high leg kick allowed you to generate more power,” he wrote. “I also used to throw my hands back over my head, as the older pitchers used to do, because I remember thinking that this old-school style was ‘cool.’ ”

And with that, things come into focus. It’s forty-six feet from the back of the plate to the front of the pitcher’s rubber. Lauri throws at sixty mph, giving the batter 0.52 seconds to react. Lauri is on the mound, feeling the laces for a two-seam fastball. I tighten my Mizuno batting gloves on the Slugger. He checks the signs, lifts his hands above his head, and brings his left knee high to his chin. Then he fires a pitch down the center, groin-high.

There’s something instinctual to a batter’s reaction, like the cremasteric reflex. I hear the Slugger’s clangor, feel the satisfying thwack. Lauri lurches his head back as the ball zips by him. It rolls among clovers and blades of grass. I am running home. I am, for that moment, the Sultan of Swat.

Ross Kenneth Urken is a writer in Manhattan. Read more of his work here.

The Art of Marbling

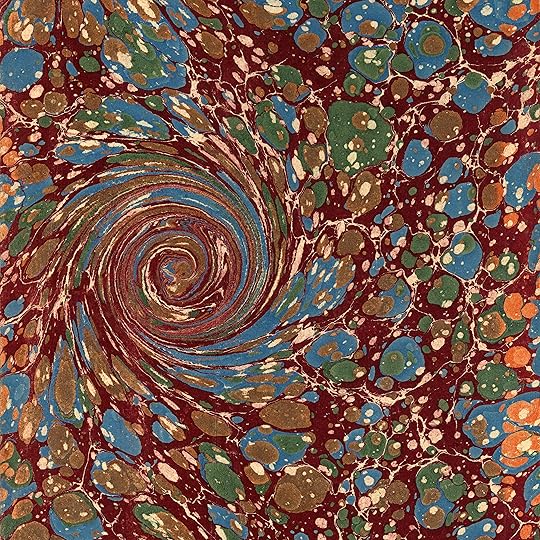

From Oguz Uygur, a Turkish filmmaker, comes this video on ebru, or marbling, a design style in which artists create intricate patterns using floating, vividly colored inks and then transfer them to paper. Uygur’s parents are skilled marblers—they’re the ones you see here—and his video gives a sense of the patience and precision required to bring off such impressive patterns as “the nonpareil marble,” “the peacock marble,” or “the entwined comb marble.”

In order to make the colors “float,” you’ll need a bed of viscous mucilage, known as size. You can make this from moss or seaweed extracts—you know, whatever you have lying around the house. Once that’s in place,

The colors are then spattered or dropped onto the size, one color after another, until there is a dense pattern of several colors … Each successive layer of pigment spreads slightly less than the last … Once the colors are laid down, various tools and implements such as rakes, combs, and styluses are often used in a series of movements to create more intricate designs.

Rookie has a helpful guide to do-it-yourself marbling (no viscous mucilage required—just turpentine). For truly dedicated autodidacts, there’s Josef Halfer’s The Progress of the Marbling Art: From Technical Scientific Principles, an 1894 manual that goes into exhaustive (and perhaps exhausting) detail on every facet of the art. Its distinctions are fine: Halfer reminds that the gray snail marble is not to be confused, for instance, with the common greenish-gray snail marble, or the grayish-green snail marble. They’re different.

Marbling from an 1880 French book.

Life After the Bench, and Other News

Garry Winogrand, World’s Fair, New York City, 1964

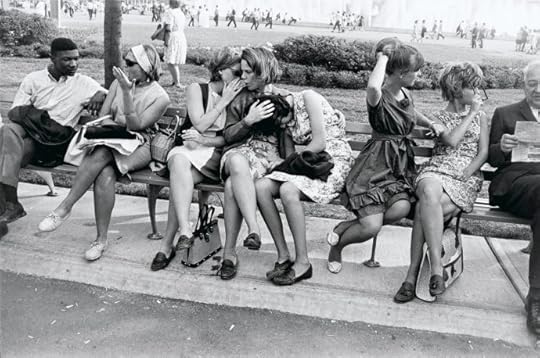

Catching up with two subjects from a 1964 Garry Winogrand photograph—that one, up there—fifty years later: “I never saw a photographer, or anyone taking our picture. It was not like today, when people are taking pictures every minute. We were just a bunch of girls out having fun. Why would anyone take our picture?”

Whither the book jacket? “If, for the majority of books, the jacket no longer serves a protective function, it still shields the subcutaneous narrative metaphorically. As we spend more of our reading time in digital, disembodied, notional environments where texts lack differentiation and may easily leach into one another unconstrained, covers (and physical books in general) remain part of an anxious cultural effort to corral and contain the boundless.”

Humor is dead, subtlety is dead: Facebook is now proposing to append a “satire” tag to any shared article with a comic bent—the equivalent of winking after every joke.

Sensory deprivation used to be a form of torture; the CIA thought it could help with brainwashing. Now it’s a form of therapy.

“Escaping into video games is something that people have been doing since video games were first invented … Traditional media cannot provide the amount of hours of entertainment that games can, exercise and sports are limited by physical exhaustion and most other hobbies or activities would be impractical if pursued to the same extent … It could be argued that the last two decades or so through which the video game has risen to prominence have created a boondoggle of incalculable proportions.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers