The Paris Review's Blog, page 675

August 8, 2014

What We’re Loving: Atomic Weapons, Augustus, Ang Lee

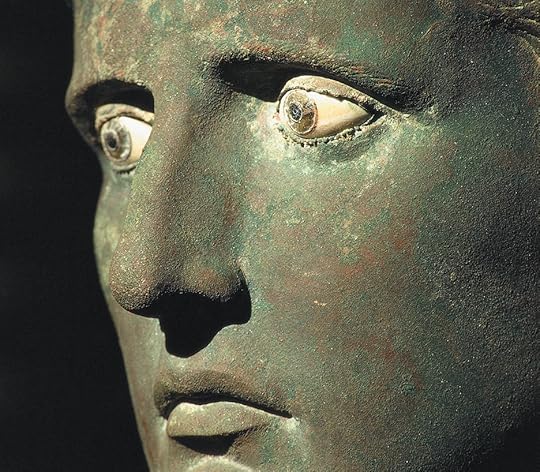

The bronze head of Augustus with glass and alabaster eyes; from Meroë, Sudan, ca. 27–25 BC. Photo: British Museum

“I have worked in an atomic weapons depot, a Veterans’ psychiatric hospital and a perfectly awful mental hospital for juveniles, and in all of these places I did what I was told to do, and gave my notice when I had had it with the life they offered.” So begins Mike Kirby’s “Diary” in last week’s London Review of Books. With his description of making and testing bombs, Kirby shows you don’t have to picture the stuff a writer describes—you don’t even have to understand what he’s talking about—to follow his train of thought or remain under the spell of his voice. (And no, this staff pick has nothing to do with our special summer offer—but, yes, right now you can get a year of both the LRB and The Paris Review for $60.) —Lorin Stein

There are so many things about John Williams’s Augustus, the newly reissued winner of the 1973 National Book Award, that shouldn’t work. First, it’s an epistolary novel—a form that always stretches credibility, by my lights, because to advance the plot its letters must make long forays into exposition, and real letters seldom do. Two, it tracks the lives of white men who’ve been dead so long their names are shrouded in the dust of antiquity: they can be hard to tell apart. Three, it deigns to speculate on the inner life of the most famous of these men, the founder of the Roman Empire, and that kind of conjecture almost always seems presumptuous in a novelist. And yet Augustus is gripping, brimming with life. Daniel Mendelsohn’s smart, thoughtful introduction gets at why: central to the novel, he says, is “the conflict between individuals and institutions”—a fecund concern in any age. But none of its drama would bear fruit if Williams weren’t such a close observer of human behavior. “The concerns of this spectacular historical saga are intimate and deeply humane,” Mendelsohn writes. “Like the best works of historical fiction about the classical world … Augustus suggests the past without presuming to re-create it.” —Dan Piepenbring

For forty years, Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 film Wake in Fright was believed to be lost—the editor Anthony Buckley made it his mission to find a surviving print. It’s one of the most shocking and uncompromised studies of male degradation ever put on celluloid. By the end of the film, we’ve seen drunken fistfights, rape, and a gruesome moonlight kangaroo hunt; we’ve watched as a cultured schoolteacher comes to emulate the chauvinistic drunkards he despises. Though it was reviled upon its initial release, the film, along with Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout and Tim Burstall’s Stork, paved the way for the Australian New Wave and gave filmmakers such as Fred Schepisi and Peter Weir the courage to make films like Mad Max and The Devil’s Playground. The Australia of Wake in Fright is populated by men who have become accustomed to the harshness of nowhere. Welcome to hell. Stay a while. —Justin Alvarez

Hot on the (platform) heels of last night’s seventies-themed celebration of Rick Perlstein’s The Invisible Bridge at the office, I offer a rather different rendering of the age of synthetic fibers via Ang Lee’s 1997 adaptation of Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm. Set during Thanksgiving 1973, the film captures, with Lee’s signature precision, the full gamut of seventies escapism—and yeah, there’s a swingers party. But beneath the water beds and shaggy hairstyles, this is a movie about adolescence; its cast of teenagers wants desperately to experience adult life, and yet they’re utterly unprepared for the series of very adult situations in which they find themselves. The scene in which two characters question whether or not their parents will get divorced has an unforced, awkward closeness to it that rings true. Lee gets at something difficult to describe about coming of age: often it’s not a gradual process but a baptism by fire. —Chantal McStay

And while I’m on the topic of the seventies: I can only listen to the Bee Gees for so long before thinking of this ingenious little ad for MTV’s The State, which aired in 1994. The commercial, set to Robin Gibb crooning “I Started a Joke” (in perhaps the most wonderfully literal application of that song ever), uses the underappreciated sketch show’s absurdly negative reviews as selling points. Michael Ian Black, Ken Marino, and the rest of the crew mope around as pithy put-downs like “Significantly less than sporadically funny” and “More miserable crap” flash across the scene—twenty-eight seconds of pure delight. —CM

In his book Jokes: Philosophical Thoughts on Joking Matters and his essay “Humor,” the philosopher Ted Cohen presents a lucid, accessible theory about jokes: that there cannot and should not be any such theory. Like art, he says, jokes transcend explanation—it’s the inexplicability and unexpectedness of the thing that usually accounts for its being funny. What we are able to say about jokes is that they form a sense of community, and Cohen is smart about this: he says that joke-telling provides occasions to see the amusement in me echoed by the amusement in you (provided you like my joke, of course). These moments of mutual recognition are not, unlike the jokes, to be taken lightly. —Parker Henry

Overheard in New York

Georgios Jakobides, The First Steps, 1889

Now that it is going to be sold, my grandparents’ house, and the summers we spent there, seem cloaked in romance. I remember the trips to the thrift store, the games in the phalanx of sheds, the maple bars from Red’s Donuts, nature walks with my uncle, reading Green Mansions in the woods. It is easy to gloss over the rest.

It was a place of strong smells. Mint in the yard. Eucalyptus trees on the drive. Talcum powder and Lysol and always a potato rotting somewhere in the kitchen. It would have been a good place to be blind. Or, it would have if every inch hadn’t been covered with constantly shifting stuff.

I can’t seem to stop thinking and writing about my grandparents, lately. Well, they’ve been on everyone’s minds as they clear the property and sort through the family politics. I suppose I’ve been fumbling for some sort of eulogy. I’ve started to write about singing gay nineties songs around the piano, about family holidays and the day we all dressed in costumes for a group portrait. But I don’t think any of that really tells the story. If I were to try to say goodbye with one story, I think it would need to be a conversation I overheard one day. My grandfather called every evening; I walked into the kitchen to find my mother on the phone.

“Has Mom agreed to this?” A beat. Then, exasperated, “Then that’s not a suicide pact, Dad; it’s a murder-suicide.”

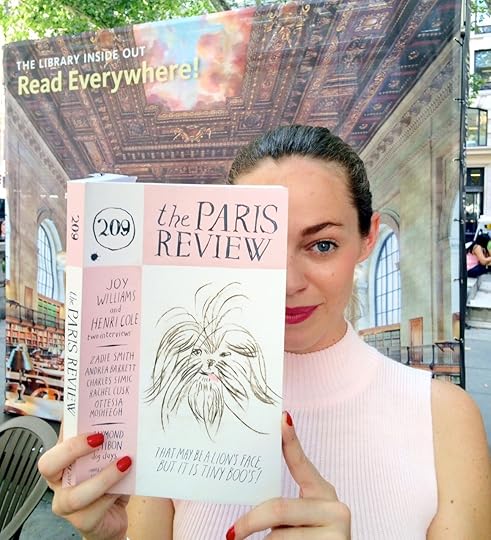

Read Everywhere, Part 7 (or, the Hashtag Wars)

The Paris Review’s Hailey Gates with a remarkably familiar slogan outside the New York Public Library.

This week, the New York Public Library launched a campaign to celebrate “the excitement and personal joy of reading”—an initiative we wholeheartedly support.

As do celebrities, apparently: the NYPL has photos of Hillary Clinton, Mindy Kaling, and the cast of Big Bang Theory reading contentedly in various corners of the earth.

There’s just one problem. The slogan for their campaign is Read Everywhere. And, like, not to get all petty or whatever? But we’ve been using that slogan for weeks to promote our summer subscription deal with the London Review of Books. (We’re having a Read Everywhere photo contest now, too, with lavish prizes.)

Our initial impulse was to retaliate, swiftly and with style. But how? A lawsuit would be costly. Vandalism would be unseemly. And some kind of ritualistic book burning … well, that wouldn’t be terribly stylish.

We settled on a time-honored subversive tactic: appropriation. Above is Hailey Gates, our head of advertising and promotions, in a defiant act of détournement. In Bryant Park—where plainclothes librarians and aides-de-camp are legion, and the lions are always watching—she managed to evade detection. We commend her for her bravery.

Your move, NYPL.

The Open Book Book, and Other News

Doug Beube’s contribution to the Open Book Project “reimagines the book as a reconstructible sculpture of maps and zippers.” Image: the Open Book Project, via the Atlantic

James Wolcott on the scourge of nineties nostalgia: “Mostly a white people’s pastime, nostalgia used to be a pining for an idealized yesteryear, for a prelapsarian world tinted in sepia … the Internet and cable TV have colonized the hive mind and set up carnival pavilions. Now every delight is obtainable and on display at an arcade that never closes … This anxious, ravenous speedup of nostalgia—getting wistful over goodies that never went away—is more than a reflection of the overall acceleration of digital culture, a pathetic sign of our determination to dote on every last shiny souvenir of our prolonged adolescence, and an indictment of our gutless refusal to face the rotten future like Stoic philosophers.”

With the Open Book project, two professors held “experimental book workshops … to help define what the classic book—and the new book—could be.” Now there’s the Open Book book, “an amalgam of essays on and artwork made from books. ‘Not all of these books are made from and with paper-based books … We purposely sought book-like work for the Open Book exhibition that transcended paper media.’”

What does a minute feel like? Sixty seconds. What does sixty seconds feel like? A minute. “I was a lab rat in a performance-art piece on the High Line. The artist, an Argentinian named David Lamelas, arranged forty-odd people—friends, tourists, commuters, passersby—shoulder to shoulder, like an extra-long police lineup. ‘The time is now six-thirty-five,’ he announced, looking at his phone. Starting at one end of the queue, we were each supposed to wait for what we estimated to be one minute and then call out the time.”

In the UK, a new edition of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has a remarkably creepy cover. “It features a cover photograph of a young girl in make-up and marabou feathers, perched on her mother’s knee with the blank-eyed expression of a doll.”

Eighteen months ago, Steven Soderbergh retired from filmmaking. Now he’s made The Knick, a grisly TV drama series about a hospital in the earliest days of the twentieth century: It’s “a gritty glimpse of Gilded Age New York … The first ten minutes of the premiere are among the most gruesome I’ve seen this year, as [the doctors] attempt an emergency C-section on a woman with placenta previa, an operation they have already failed at twelve times before.”

August 7, 2014

I Scream

Photo: Zechariah Judy

As a child in suburban Connecticut, I had always considered the purl of the Good Humor truck to be more closely akin to a cricket’s chirp or the sound of summer rain: a seasonal gift, wreathed in sweet associations … [but] it is a grave error to assume that ice cream consumption requires hot weather. If that were the case, wouldn’t Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield have established their first ice cream parlor in Tallahassee instead of Burlington, Vermont, which averages 161 annual days of frost? … Wouldn’t John Goddard, an outdoorsman of my acquaintance, have arranged for a thermos of hot chicken soup instead of a half gallon of French vanilla ice cream with raspberry topping to be airdropped to him on the summit of Mount Rainier? And wouldn’t the Nobel Prize banquet, held every year in Stockholm on the tenth of December, conclude with crepes Suzette instead of glace Nobel? As the lights dim, a procession of uniformed servitors marches down the grand staircase, each bearing on a silver salver a large cake surrounded by spun sugar. Projecting from the cake is a dome of ice cream. Projecting from the dome is an obelisk of ice cream. Projecting from the obelisk is a flame. When the laureates—who have already consumed the likes of homard en gelée à la crème de choux fleur et au caviar Kalix and ballotine de pintade avex sa garniture de pommes de terre de Laponie with no special fanfare—see what is heading their way, they invariably burst into applause.

—Anne Fadiman, born today in 1953, from her essay “Ice Cream”

The Comic Voice: An Interview with Christina Nichol

Photo courtesy of the Overlook Press

Last month, Brooklyn’s powerHouse Books hosted Norman Rush, Marco Roth, and Christina Nichol to discuss Nichol’s debut novel, Waiting for the Electricity . Set in a post-Soviet Georgia, rife with power shortages, the book stars Slims Achmed Makashvili, a maritime lawyer navigating the perplexing, often hilarious vagaries of life in a corrupt republic. Slims yearns to visit America—he writes letters to Hillary Clinton and applies to a business program she sponsors—where he hopes to discover a land of stupefying efficiency. But when at last he arrives in the U.S., the vision of progress is not what he’d hoped.

Nichol has taught English in India, South Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, and, of course, Georgia; her experiences abroad inform much of Waiting for the Electricity’s observant wit. With Rush and Roth, she discussed the direction of the comic novel, fiction’s bearing on foreign policy, and a State Department official with a ukulele.

ROTH

Christina, how did you end up in Georgia? How did you join the great English-teaching enterprise that is this new American century?

NICHOL

As a kid I went to the Soviet Union with my grandfather, who braved a hundred Americans and a hundred Russians on a boat down the Volga River. This was during the eighties, and I sort of fell in love with Russia—I continued to go back to witness the transformation of communism into capitalism, which I saw as an amazing and tragic story of the twentieth century. I’d been to Kyrgyzstan, too, and as an adult I was trying to get back. I applied through this foundation, and they said, Well, we have Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia available. I’d once seen some Georgian folk dancers, and they were really amazing, so I decided on Georgia, knowing nothing about it.

ROTH

And Norman, you spent some time in the Peace Corps.

RUSH

Not technically. [Elsa and I] were co-country directors in the Peace Corps in Botswana from ’78 to ’83. But the formative effect of being outside the country for a long period of time is certainly the same—having that be a catalyst to a kind of uncheckable literary impulse, looking at a different part of the great evolution that’s taken place. But Christina, you said something intriguing—that you thought the conversion or the evolution of communism to capitalism was a great tragedy. That’s certainly not the State Department opinion. Are you a Bolshevik?

NICHOL

I suppose I’m thinking of how it was done to hold up America as an example. In communist nations, they’d heard all these terrible things about how capitalism works—someone gets money and then doesn’t provide the service he’s been paid for—and they’d say, Well, that’s the free market economy for you! Then, under capitalism, they began to live the kind of ideology of the propaganda they’d been brought up with. It was actually an even worse form of capitalism than ours.

RUSH

Yours is a glorious comic narrative, and there’s something slightly odd in talking about it in the midst of terrible political tragedy, the murder and carnage taking place around the world—a kind of carnage in which, as humans and as Americans, we’re all to some degree implicated. But it isn’t strange, actually, when you think about it. Comic narrative, especially high comic, in textual form, is very important for two reasons. One, it relaxes us and returns us. It disengages us from the essential tragedy, the base tragedy, and the unnecessary tragedy that we encounter as human beings. And it teaches a kind of distance. It has a way of recharging, of remaking our willingness to be open, to have strength in the world, and to work within it. This novel is a remarkable entry into the world of comic fiction. If you look at the history of what’s considered funny in terms of narrative fiction, it’s been pretty much a male reserve. Examining, say, English Anglophone writers—novelists, not short-story writers or nonfiction writers—there’s Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm, but suddenly now there’s Lydia Davis, Rivka Galchen, and an explosion of the comic subject.

NICHOL

I was in Kosovo last year, and they love Facebook. They’re constantly posting aphorisms. One that I read recently was by a man. He wrote, “Humor requires intelligence and honesty. That is why women love men who are funny.” And I wanted to write back, Well, what about women? They didn’t know how to deal with me in Kosovo. They didn’t understand that women can be funny.

ROTH

Were you worried at a certain point that your reader would only be laughing at the malapropisms and the funny folk ways of this dorky character? The short way of referring to this is the Borat problem. Did you ever have this moment of crisis when you feared you were betraying your Georgian friends? Or did you feel like they’d understand, because what you saw there led you to believe that comedy could work in the ways that Norman suggested?

NICHOL

I’d started to have some crisis if I’d been away from Georgia for too long. I’d think, How is this possible? This country actually exists like this. They actually do hang their paintings upside down. For me, comedy is about the disruption of power. It’s about taking the formal and informalizing it, taking the informal and formalizing it. That’s the power that Georgia understands, and that’s the way they’ve been able to live, to stay sane—by turning their suffering upside down, turning what they have no control over upside down. I always felt that I was laughing with them. When I’d show parts of the book to them, they would always feel so honored. They’d say, You’ve captured our spirit.

RUSH

I want to recommend a book called The House of Nire, a long Japanese novel by Morio Kita, published in the nineties. It’s based on a family that runs an insane asylum in Japan, in the period of about 1905 through the Second World War. You can see what a wonderful metaphor that is—the only sane people are the ones running the insane asylum. But I was going to ask about your influences.

NICHOL

I’ve discovered that Georgia, until recently, didn’t really have a strong literary tradition. They had a strong finger-puppet-theater tradition, a strong singing tradition, and theater and film. But they did have a few writers whom they were really proud of. One was this Nodar Dumbadze, and another, this Abkhazian writer, Fazil Iskander. Andrei Bitov, too. A lot of Russian Soviet writers. And what I noticed is that they can’t help but write in that comic tradition. When you get to Georgia, it just infiltrates you. You take a walk on a mountain and you feel this comic voice infusing you.

ROTH

I wanted to ask both of you about writing in the voice of the opposite gender or sex. Christina, your novel is told in the voice of a male narrator. And Norman, Mating is famously narrated by a woman, and parts of Subtle Bodies are narrated in the voice of a woman. Slims is looking for the center of national Georgian identity, right? The essence of Georgia. And yet, here you are, a Georgian male impersonator. Do you think there is a Georgian national identity? Do you think this notion of national identity gets overplayed, particularly by Americans?

NICHOL

The male voice came to me with the phrase, My name is Slims, and I live in the twelfth century. Once I had that phrase, I had the voice. I couldn’t really escape. This person was living with me, and when I came back to America, he was constantly sitting on my shoulder, making snide comments about American culture. As for the Georgian national identity, when I was there they were recovering from living under the Russians, whom they did not like. They were trying to find an identity. As Slims’s line suggests, they thought of the twelfth century because that was when they owned the most land, and they thought, Well, that was our most noble time. I think they were trying to portray themselves to me, an American, as a noble people. For example, I went to Tbilisi with this friend of mine, and he insisted that he buy me a sword. We were walking down the street, I was holding onto this sword, everybody we passed applauded. We got to his apartment, on the twelfth floor, and starting cutting potatoes with the sword, and I noticed there was one bed and one blanket, and I start getting a little bit nervous about the sleeping arrangements. I guess he noticed, because he took the sword and threw it on the middle of the bed, and he said, If I cross that sword, kill me with it in the morning. I don’t know if he would have done that to a Georgian girl.

The male voice came to me with the phrase, My name is Slims, and I live in the twelfth century. Once I had that phrase, I had the voice. I couldn’t really escape. This person was living with me, and when I came back to America, he was constantly sitting on my shoulder, making snide comments about American culture. As for the Georgian national identity, when I was there they were recovering from living under the Russians, whom they did not like. They were trying to find an identity. As Slims’s line suggests, they thought of the twelfth century because that was when they owned the most land, and they thought, Well, that was our most noble time. I think they were trying to portray themselves to me, an American, as a noble people. For example, I went to Tbilisi with this friend of mine, and he insisted that he buy me a sword. We were walking down the street, I was holding onto this sword, everybody we passed applauded. We got to his apartment, on the twelfth floor, and starting cutting potatoes with the sword, and I noticed there was one bed and one blanket, and I start getting a little bit nervous about the sleeping arrangements. I guess he noticed, because he took the sword and threw it on the middle of the bed, and he said, If I cross that sword, kill me with it in the morning. I don’t know if he would have done that to a Georgian girl.

RUSH

It’s exceeding the extended narrative fiction form for comic purposes that represents such an unusual change. I think there’s a confidential war between men and women that’s been going on for a long time. Great gains are being made incrementally along the way. Taking over contested spots in literature is part of gaining expressive property. But I think it’s only the beginning. This kind of comedy is also part of what we call the media advance of comedy. That’s been huge, too. So it’s happening not only in print, in text, it’s happening elsewhere, on YouTube for example.

ROTH

In some ways, you could say that female comedy came to TV and movies first, and only latterly has gotten into the novel. But there are some examples. Ivy Compton-Burnett—

RUSH

She’s actually a good example, because she’s not really funny. She’s super ironic, but she’s not funny the way Christina is. The other great American woman comic writer, it seems to me, is Flannery O’Connor. But she has written a lot that’s quite Gothic to an extent that’s it’s kind of funny. Again, though, it’s not quite the same. This is the real thing. This is humor like Twain did it, or Dickens. Different.

NICHOL

When I was applying for this job in Kosovo, I didn’t really know much about it. I thought it was a Slavic country. The embassy called and tried to sell me on it. They said, Oh, it’s like The Sound of Music, fruit trees and wonderful people, happy. They didn’t ask me a single question, so at the end, I thought, Well, I should probably talk about myself. So I said, Oh, I think I would really fit in there. I really understand Slavic humor—the light at the end of the tunnel is actually a train coming in your direction. And there was this silence. And the man said, No, we are not a Slavic culture. This is Albania. They are more optimistic.

ROTH

You’re at the cutting edge of what could be called a form of American imperialism, in the way that in the nineteenth century, the British Empire would send missionaries to far-off lands. When you were teaching English, did you feel like you were, in a quiet way, supposed to be an evangelist for the great American way of life?

NICHOL

I did feel conflicted about the idea of teaching English. I would secretly tell my students, I’m teaching you English so you can protect yourselves against us. They would admit it—We want the English, but we don’t really want the values that come with it. In Kosovo, tourists would think, Oh this is where the Serbs fought. That was the image they wanted to keep, a picture of the Serbs bombing a particular house. They weren’t noticing the texture of life—what about this guy who’s really upset because his boss keeps taking a picture of his bald head and putting it on Facebook? What I found in Georgia was a kind of emotional intelligence. Their depth of commitment to one another was so deep that I wanted to portray it. Teaching English in these other countries has always been a means of hearing their stories, of humanizing them, and of disrupting the pervasive mainstream image.

ROTH

Is it fair to say that Americans don’t realize the extent to which we’ve saved the world from the perils of fascism and communism and bombing only to present them with ordinary humiliations? And it’s those ordinary humiliations that add up to ideologies—

NICHOL

When I got the job, I didn’t realize how much they wanted us to introduce American culture. They wanted us to talk about Halloween. Why a Muslim culture needed to celebrate Halloween, I’m not sure. And there was a time when the embassy invited a gay couple to the library in Kosovo to talk about gay rights. The library director said, Okay, the embassy’s coming to give us a talk about gay rights. We need to collect a lot of people. Just make sure nobody understands English. I do tend to kind of demonize our foreign policy, but I have this former boss at the State Department who would e-mail me, and really what he wanted to talk about was his accordion. I realized that they’re bureaucrats, but they’re really craving that lightness, craving some sort of meaning amid these bureaucratic jobs. As you were saying, comedy is a way in. He found out that I had published a book, and all of a sudden he wanted to sponsor me to read at all the different American embassies around the world. I was like, Great, but you haven’t actually read it yet. Just a couple days ago he got to chapter 10—the book is filled with a lot of proverbs, and he found one he really liked. It inspired him to write a little song. The proverb is, The tall one wouldn’t bend, the short one wouldn’t stretch, so the kiss was lost. Imagine this guy in Washington, in the State Department, on his ukulele, just playing this song.

RUSH

I think that’s so wonderful that you do something with that. There’s nothing like it. There’s actually a kind of a developing, it’s not exactly a genre, but there are some good novels by Americans about the transition from communism to capitalism. I don’t know if you know Caleb Crain’s Necessary Errors. It’s about a young gay guy teaching English in Prague after the Velvet Revolution. It’s quite good, quite sad. The common theme of all of these novels is a baffled sadness about the way things turned out—very moving. And true to feeling.

ROTH

I wanted to ask about the use of folk songs in the novel.

NICHOL

It’s quite something to be eating dinner and then to have the entire dinner table erupt into some perfect harmony. The people get up and start to dance. They all know these songs. I can’t vouch that they’re perfectly translated in the book, because I was usually in a slightly inebriated state when I heard them—which is the way you’re supposed to hear them. Here we pair wine with cheese, there they pair wine with song. It’s a very emotional experience. I’d never lived anywhere that honored sadness as much as they do. A lot of these songs are sad, but they allow time to feel that sadness. They don’t try to run away from it. The songs are a kind of guide for the sadness.

[Nichol’s editor, Mark Krotov, interjects.]

KROTOV

You said something to the effect that you didn’t want to write a novel that was going to have a kind of traditional—whatever that might mean—Western teleological direction. You didn’t want a novel that would begin and end in ways that we’re used to. Could you talk a little bit about the plot and resisting it as you were writing?

NICHOL

I had the sense that the traditional Western narrative sustained capitalism in a way—it was all about the hero overcoming the obstacles. This individual, internal quest. I wanted to portray a character where the internal and external were in alignment, because the external was his commitment to his community. To have some sort of schism there seemed so Western to me. So what I was trying to do was to create a voice of community.

RUSH

Would you object to its being called a shaggy dog story? I’m saying this with all respect, because you succeeded to achieve. Your character is not someone who sets out with a problem, solves it, and then finds a community to enjoy sweet success. He has nothing to do with the arrival of electricity, which, in the novel, changes the fate of the future. It is very brave to write a shaggy dog story. It’s something that people are going to have to get used to, because a lot of them are in print now, including a very long one, not yet finished, by Karl Ove Knausgaard. In a way, you’re part of a turn among writers against identifiable preconceived plot. More power to you.

Norman Rush is the author of Whites, a collection of stories; and the novels Mating, Mortals, and Subtle Bodies.

Marco Roth is the author of The Scientists: A Family Romance, and a founding editor of n+1.

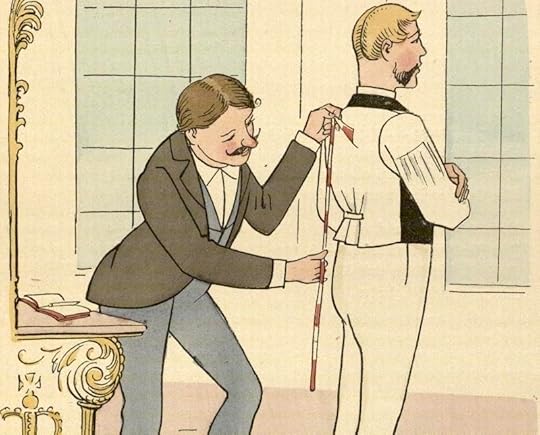

Suits

From What Should I Be? (Was soll ich werden?) (1888), a picture book by Lothar Meggendorfer.

Yesterday I went suit shopping with my brother. The suit was to be a birthday gift from my parents; I’d been entrusted with the task of supervising the purchase. We started out in a well-known British chain. “He’s looking for a suit,” I announced.

“Are you two getting married?” asked the salesman.

“We’re siblings,” we said at the same time.

“That would be weird, then,” he said.

After this, I was paranoid. “Our parents are giving him a suit for his birthday,” I would announce loudly. Or, apropos of nothing, “I’m his sister.”

When, finally, we went to a tailor, I decided to further clarify the situation by being abusive while my brother was measured.

“We couldn’t find a suit off the rack,” I informed the tailor, “because he has the build of an undernourished Victorian chimney sweep.”

“You’re a perfectly normal size,” said the tailor.

“Maybe if you’re used to suiting children and midgets!” I scoffed. No one said anything, so then I excused myself.

I’m not particularly proud of this display, but I think a little discomfort in these situations is natural. Indeed, it can take even stranger forms. One friend said he particularly dislikes people assuming he’s on dates with his sister not merely because it’s creepy, but because he hates their thinking he has so little chemistry with his girlfriend.

I had always figured those families who all look uncannily alike had it easier in these situations. But I had reckoned without human weirdness. “It must be great that you’ve never once had to worry about someone thinking you and your sister were a couple,” I said to a friend with a nearly identical younger sibling. “Are you kidding?” he said. “I worry that people think I’m such a pathological narcissist that I have to date someone who looks exactly like me!”

So, there’s that.

Announcing Our #ReadEverywhere Contest

At the beach.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock—or out in the world, pursuing your aestival fantasies instead of reading the Internet—you’ve probably heard about our terrific joint subscription deal with the London Review of Books, and you’ve seen the photos our readers have posted under the #ReadEverywhere hashtag.

But now that the longueurs of summer have settled on us, it’s time to up the stakes. We’re having a contest. From now through August 31, post a photo of yourself reading The Paris Review or the London Review of Books on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook—use the #ReadEverywhere hashtag and one of our magazines’ handles. (Those of you who have already posted photos, fear not—your work is in the running already.)

We’ll pick our three favorites—and just to show we mean business, here are the fabulous prize packages that await those lucky contestants:

FIRST PRIZE ($500 value)

From The Paris Review: One vintage issue from every decade we’ve been around—that’s seven issues, total—curated by Lorin Stein.

And from the London Review of Books: A copy of Peter Campbell’s Artwork and an LRB cover print.

SECOND PRIZE ($100 value)

From TPR: A full-color, 47" x 35 1/2" poster of Helen Frankenthaler’s West Wind, part of our print series.

And from the LRB: Two books of entries from the LRB’s famed personals section, They Call Me Naughty Lola and Sexually, I’m More of a Switzerland.

THIRD PRIZE ($25 value)

From TPR: A copy of one of our Writers at Work anthologies.

And from the LRB: An LRB mug. (Never one to be outdone, the LRB is actually including a tote bag, some postcards, a pencil, and an issue with all of the prizes above. Retail value: inestimable.)

It’s all starting now, so get yourself a joint subscription and prepare your shutter finger. See you in the great beyond.

When Softcore Had Style, and Other News

A still from Radley Metzger’s Lickerish Quartet, “the enigmatic tale of a decadent family’s seduction,” from 1970.

Peter Mendelsund, who designs book jackets, asked people what they see when they read. They “felt that when they read a book they loved, they saw every aspect of it. Not only that, but they felt that the greatness of a book was predicated on the fact that they were able to visualize it. ‘That character was so real,’ they’d say. That myth of the little homunculus sitting in the back of your skull, watching the author’s movie being projected onto the front of your skull—that’s really important to people. But the whole edifice crumbles when you start to ask questions about it.”

Was John Hancock’s signature really too big? “Did Hancock know that fifty-six men would ultimately sign the document when he put pen to paper? Or might he have assumed fewer signatories, and thus more space for signing? We know this much: You can’t fit fifty-six Hancock-sized signatures onto the parchment … the document would have needed approximately 5.5 more inches of vertical space to accommodate all the names—even with crammed spacing and slim margins.”

Good news for underemployed babysitters: Taking your kids to a gallery is a “total waste of time,” according to the artist Jake Chapman. “He says that standing a child in front of a Pollock is an ‘insult’ to the American who pioneered the abstract expressionism. ‘It’s like saying … it’s as moronic as a child? Children are not human yet,’ the father-of-three declared.”

Questioning Shakespeare’s conservatism: “Rebels and usurpers in Shakespeare's plays are always the bad guys … Rebellion against one’s superiors is presented as a matter of misguided jealousy and intrinsic spite.”

“A maestro of aspirational porn, Radley Metzger populated his soft- and hard-core films of the 1960s and ’70s with Continental swells whose luxe dwellings and vast expanses of land made for optimal prime pleasure domes … [he] elevated his randy projects with sumptuous production values, his meticulous decor and mise-en-scène long outmoded in today’s quickie online porn.” (For the curious, eight of Metzger’s films are coming to Lincoln Center.)

August 6, 2014

Birthday Burger

Happy birthday, Andy Warhol. Go on, have that Whopper! You’ve earned it. Ketchup? Sure! Ketchup! Have the whole bottle!

No, no, take your time. We’ve got all day.

This clip is from the Danish filmmaker Jørgen Leth’s 66 Scenes from America (1982). He said of the performance:

[Warhol] is told that he has to say his name and that he should do so when he has finished performing his action, but what happens is that the action takes a very long time to perform; it’s simply agonizing. I have to admit that I personally adore that, because it’s a pure homage to Warhol. It couldn’t be more Warholesque. That’s of course why he agreed to do it.

But we don’t know this. Maybe he was just hungry.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers