The Paris Review's Blog, page 676

August 6, 2014

Jessoterica

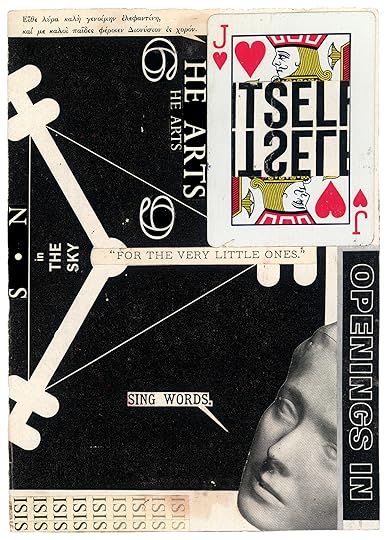

Interior page from From Force of Habit, 1966, collage book, approx. 8" x 5 ¾ ". Courtesy of the Odyssia Gallery, New York, NY.

Jess Collins, better known as just Jess, was a painter and collagist born today in 1923. Jess spent most of his life in the Bay Area, where he lived with his longtime partner, the poet Robert Duncan. (The latter died in 1988; the former in 2004.) In our Fall 2012 issue, The Paris Review featured some of Jess’s work in collage, or “paste-ups”; as our own Nicole Rudick explains,

Jess and Duncan shared a lifelong interest in salvaging esoteric bits of culture past—in Jess’s case, Goodwill cast-offs, Dick Tracy and Krazy Kat comics, advertisements for Tabu, and Life magazine, but also tarot cards, Renaissance chapbooks, Greek mythology, Victorian engravings, and Arthurian legend. As he worked, he would choose from among thousands of carefully cut-out images, painstakingly organized by subject. His recollection of an abandoned prospector’s shack, which he discovered as child, aptly describes his own studio: “a little palace assembled from ... almost any type of found object you can imagine.”

If you want to explore more of Jess’s work, earlier this year the Times ran an excellent piece on him, Duncan, and their coterie:

Where Duncan’s art explodes, Jess’s only threatens to, which is much more interesting … Jess is best known for his collages, which he called paste-ups: staggeringly intricate symbolic narratives pieced together from bits of scientific treatises, muscle magazines, art history books, cartoons and popular periodicals like Life and Time. This work is not lost-in-the-clouds stuff. A 1968 collage in response to the war in Vietnam called “The Napoleonic Geometry of Art—Given: The Pentagon in the Square: Demonstrate: The Hyperbolic Swastika,” is about as pointedly angry as art can be.

And Hyperallergic published a great essay in February, wherein Christopher Lyon identifies Duncan and Jess’s

sustained faith in make-believe—that one can simultaneously be oneself and be many selves, past and future; that one can embrace the everyday and simultaneously experience in it an intensified poetic reality. Embedded in art or poetry, make-believe expresses a faith that someone in an unknowable future will engage with one’s work and re-experience that intensification of the moment—this is existentialism recast as myth.

Stuff and Nonsense

An illustration by H. M. Bateman for the Ministry of Health’s WWII-era “Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases“ campaign.

Among other things, E. B. White has the distinction of being one of the few writers to really express the misery of seasonal allergies. In “The Summer Catarrh” (1938) he details Daniel Webster’s struggles with hay fever, proclaiming, “there is a fraternity among those who have been tried beyond endurance.”

He exaggerates for effect, of course. Part of the misery of allergies is the knowledge that, generally speaking, they’re as toothless as they are persistent. They’re definitionally endurable—albeit at the expense of that elusive thing, “quality of life.” (“Quality of life,” much like the box we’re supposed to think outside of, seems to be a thing that exists primarily in negative space.) Prescriptions, Claritin, neti pots, humidifiers, special pillow covers: they’re all just panaceas. When you have allergies, you have allergies. To the outsider, it must seem somewhere between hypochondria and a cold—unpleasant, certainly, but mostly just annoying. And it is annoying. It is the least romantic thing in the world. Sniffling, snoring, “itchy, watery” eyes and a malaise that feels like nothing so much as a faint and chronic hangover … these do nothing for the soul at all.

Allergies are a relatively modern malady, the product of industrialization, urban living, and deforestation. Almost any diet craze worth its salt will claim a diminution of symptoms as one of its benefits. If the subject interests you, try Gregg Mitman’s excellent Breathing Space: How Allergies Shape Our Lives and Landscapes. It’s a colorful read—the allergy industry is mind boggling—but also a sobering one, as discussions of pollution and urban planning are inextricably linked with cynical questions of politics and marginalization. (And quite often, the lifelong health effects are very far from benign.)

As a child, I had no patience with my parents’ allergies—their constant sniffling, their inability to smell and taste certain things, their chronic sense of being unwell without ever really seeming sick. When I got older, I suddenly appreciated why they’d had boxes of aloe-soft tissues in every room in the house. I even understood why they moved to Arizona—although that still strikes me as a drastic step.

They, whoever “they” are, say it is a bad year for allergies, but it always seems to be a bad year for allergies. I even forget which the bad seasons are supposed to be, since pollen and ragweed and rotting leaves all seem awful in their own unique ways.

E. B. White, again, has the right idea. As usual, he is magnanimous without mawkishness:

Webster, even though he knew very little about the cause of hay fever, must have found, just as I find, in this strange sensitivity to male dust and earth’s fertile attitude a compensatory feeling—a special identification with life’s high mystery that in some measure indemnifies us for the violence and humiliation of our comic distress that makes up for the unfulfillment of our most cherished dream.

The Lean, Mean, Star-Making K-Pop Machine

How Korea mints its pop stars.

From the cover of The Birth of Korean Cool.

Korean pop’s star-making process has suffered slings and arrows from the Western press—some allege that it amounts to modern-day slavery. It’s true that K-pop labels recruit budding stars and bind them to contracts that can last as long as thirteen years. But Korea had no other way of building a pop industry. It had to create it from the ground up.

Most famous rock bands formed independently, without the help of a producer or record label. This was never going to happen in Korea. Kids didn’t have the time to jam with friends. They were studying—all the time—or helping with the family business. Organically formed bands could experiment with new sounds or improvise or goof off, but Koreans had no such luxury. In the unforgiving Confucian culture, a young person who screws up has a hard time getting back on track. Until recently, when K-pop proved profitable, no Korean would have staked his future on music.

Lee Moon-won, a culture critic, said, “Koreans spend the same effort on everything, whether it’s college entrance exams or an office job. Korea stands for hard work.” According, a conventional K-pop contract lasts seven to thirteen years; half that time is spent training the stars. Shin Hyung-kwan, the general manager of MNET, Korea’s version of MTV, explained, “It takes time to see who has hidden talents. It’s one thing to pick some person and say you’re going to make them a star, but you have to see if they get along with each other and in society at large. If you are not careful, the whole thing can be spoiled. Westerners do not understand. The performers could get into an accident, some kind of trouble.”

Lee offered insight into the necessity of the K-pop star factory system. In the United States, he explained, the pool of hopefuls is big enough that a kind of natural triage occurs. But “the human resource pool in Korea is small … They have to take measures to be competitive internationally.”

A staggering 4 percent of the population of South Korea auditioned in 2012 for Superstar K, Korea’s biggest televised singing competition. That’s 2.08 million would-be K-pop stars competing in a single year in a country with a population of fifty million. By contrast, even the behemoth American Idol only has about 80,000 contestants in a given year, amounting to a minuscule 0.03 percent of the U.S. population.

The K-pop model requires music companies to invest a lot of money up front for a very distant return. It’s a paternalistic system that disciplines its stars. This isn’t just a matter of ensuring that band members get along; it also means steering them away from drunk driving, drugs, or sex scandals. K-pop star training is an education of the whole person.

But the biggest and most obvious difference, Shin said, is in the quality of the dancing. “In the United States, with the popular bands, the choreography is very different.” And by different he means bad: “If you look at New Kids on the Block, for example, the members are not really synchronized. And in Justin Timberlake’s [performances], the dancers are a bit off. Dancers in American bands are freer and go by feeling. The United States doesn’t have singers who dance really well, unless it’s someone like Michael Jackson, and that kind of talent comes around once in a hundred years.”

Dancing well isn’t enough. K-pop band members must dance in perfect synch, like clockwork. If you’ve ever seen a K-pop video, you’ll notice that while no one is Baryshnikov, they do have split-second precision. To achieve that, you have to put the band together while they’re still young and hold off their debut until they’ve learned to act as one.

To see just how manufactured K-pop is, consider that one Korean television program started four simultaneous and separate K-pop bands with a color theme. Collectively, they’re called the Color of K-pop. Two are girl groups: Dazzling Red and Mystic White. The other two, Dramatic Blue and Dynamic Black, are boy bands. Members wear color-corresponding outfits, and each band has its own character: Mystic White is innocent, Dazzling Red is sassy, et cetera.

If this sounds like a marketing plan straight out of the Gap, that’s exactly the effect the producers are going for. You don’t need to know what the individual singers’ back stories might be—who grew up in a trailer park, who started singing gospel in her church. How interesting is a twenty-year-old’s biography, anyway?

K-pop labels love stars, but not superstars: they don’t want to get into a situation in which one band member becomes indispensable. Bands are treated like consumer products from the beginning. Producers design the band they want—down to the precise look, sound, and marketing campaign—before they even audition members.

* * *

Can K-pop conquer the United States? I asked Martina and Simon Stawski, an ebullient young Canadian couple and self-professed K-pop fanatics. Theirs is probably the best English-language site for analyses and reviews of Korean culture.

Psy, they believe, is popular because he’s funny, but humor isn’t always the right approach. “Sometimes bands will try to go for humor in their videos, but it’s ehgyo [cutesy baby talk] humor. Ehgyo humor is not easily understood [outside Asia].” She’s right—it’s not. Ehgyo is a sort of setup in which a girl infantilizes herself as a means of flirtation; you can’t tell whether she is talking to her older brother or her boyfriend. It’s not quite French-style sexy-baby, like France Gall or Brigitte Bardot. It’s more innocent—picture a petulant child.

Martina had some practical suggestions for broadening K-pop bands’ appeal in the United States. “They’d have to not use a lot of makeup for guys,” she said. “The clothes can’t be too tight … some of the bands [have] too many members.”

There’s also the matter of Korea’s squeamish youth protection laws, instituted in the nineties, partly to clamp down on the sexual exploitation of children and partly to protect children from corruptive material. Record labels assign strict age limits on albums, sometimes for odd reasons. “Mirotic,” a song by the boy band TVXQ!, was originally only for purchase by those over eighteen because of the lyric “I’ve got you under my skin”—it had to be changed to “I’ve got you under my sky” to be legally sold to a younger audience. The penalties for being consigned to the nineteen+ age rating are high; it means the song in question gets no radio or TV play. When Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way Ball” toured in Seoul, her concert was limited to the nineteen+ crowd with another turn of the screw: anyone eighteen and under was barred from entry even if accompanied by an adult.

If I had to pick a male band that had a good chance of crossover success, it would be Big Bang—especially one member, G-Dragon, whose real name is Kwon Ji-young. (Dakota Fanning is reportedly a fan.) G-Dragon was in training for about eleven years before setting foot on a public stage. When I first saw him perform, I didn’t know what to make of him; he arrived solo, which for some reason made me worried for him. He has a slight build with soft features, his eyes rimmed with tons of black eyeliner—more than I used to wear even during the years when I listened to the Smiths and read Nietzsche.

He bellowed to the audience what the non-English-speaking world believes to be a universal cry: “Whassup!” Then he led the audience in a neo-Dadaist chorus.

G-DRAGON (in English): When I say GET YOUR, you say CRAYON! GET YOUR!

AUDIENCE: Crayon!

G-DRAGON: GET YOUR!

AUDIENCE: Crayon!

Weirdly enough, Korea didn’t even have crayons when I was growing up. It was a source of some wistfulness in my house, actually. The closest substitute was Cray-pas—a more sophisticated pastel cousin. I wasn’t sure I was hearing G-Dragon correctly until I saw that the giant screen behind him was showing images of crayons. And then he launched into one of his biggest hits: “Crayon.” Trust me. It’s a good song.

This essay is adapted from The Birth of Korean Cool by Euny Hong. The Birth of Korean Cool copyright © 2014 by Euny Hong. The trade paperback original published August 5, 2014, by Picador USA. All rights reserved.

Euny Hong’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal Europe, International Herald Tribune, The New Republic, The Boston Globe, and The Forward. She is also the author of the novel Kept: A Comedy of Sex and Manners. She is fluent in English, French, German, and Korean.

The Cows That Might’ve Been, and Other News

Charlotte Strick‘s preliminary designs for Lydia Davis’s latest book included these cows, illustrated by Ariana Nehmad.

“The image of a syphilitic Joyce is one that few scholars have wanted to conjure in print”—but evidence suggests that Joyce did indeed suffer from syphilis. It’s not just in his medical history but in Ulysses, where two scholars “found syphilis everywhere … Their journal article for Archives of Internal Medicine includes a two-page table listing apparent references to syphilitic symptoms throughout Ulysses … ‘The letter s hisses throughout the book as a reminder of the s in syphilis (a word that not only begins but also ends with s, as does the novel).”

In Greece, a new museum reconstructs the inventions of the ancients, “including Archimedes’ screw, the robot-servant of Philon, the automatic theatre of Heron, ancient war machines, and the famous analogue ‘computer’ of Antikythera.”

The Paris Review’s art editor, Charlotte Strick, discusses her process in designing the jacket for Lydia Davis’s Can’t and Won’t. “ ‘The Cows’ is the longest story in this collection, and cows by nature ‘can’t and won’t.’ They typically require a lot of waiting around. This sparked an idea early on in my design process … I tried an all-over wallpaper pattern of tiny cows that I imagined as a pre-printed case.”

A photo of brawling Ukrainian parliamentarians has all the beauty and compositional fluency of a Renaissance painting.

Scrabble has expanded its dictionary, adding some five thousand words—most of them are expectable neologisms like frenemy and bromance, but others are more novel: e.g., quinzhee, a shelter made by hollowing out a snow pile, and qajaq, an Inuit precursor to the Kayak.

August 5, 2014

Boule de Suif

Let’s talk about Guy de Maupassant, because he was born today in 1850 and because—why not? He’s Guy de Maupassant. As our own Lorin Stein wrote in 2010,

In a career that spanned barely a decade—the 1880s and early 1890s—Maupassant produced some 300 stories, 200 articles, three travel books, a collection of poems, three plays, and six novels, and the bulk of this production was consumed with the pursuit of illicit sex. His specialty was the conte leste, a kind of bawdy comic story we have very little of in English after Chaucer (think Boccaccio or The Arabian Nights). Maupassant modernized this tradition, testing the boundaries of what was permissible even in the Paris tabloids, where many of his stories first appeared. He was the best-selling writer of his generation.

Maupassant’s early story “Boule de Suif,” from 1880, remains a hallmark and a natural starting point. It’s about a prostitute whose refrain, like Bartleby’s, is that she would prefer not to—in this case, a Prussian officer asks repeatedly for the pleasure of her intimate company, and she invariably denies him. Unlike Bartleby, though, Boule de Suif must eventually give in, not by any defect of will but because of peer pressure.

This Prussian guy, you see, has detained her and several of her countrymen at a local inn. He’ll only allow the group to leave if Boule de Suif (or “Dumpling,” should that translation suit you, or “Butterball,” or most literally “Ball of Fat”) surrenders to his advances. And so her fellow travelers, all of whom disdain her for her occupation, find themselves begging her to succumb.

From this simple conceit, Maupassant wrings a whole novel’s supply of tragicomic tension. “Boule de Suif” is prototypical Maupassant: sexual but not psychosexual, a distinction that can seem counterintuitive after Freud and modernism. To quote Lorin again:

What most troubled and delighted Maupassant’s readers was his erotic identification with women. He saw them as sexual objects, and he saw himself as a sexual object … As he had it, even a genius couldn’t write about sensuality if he wasn’t inclined that way himself. The reverse held too. In the aesthetic battles of the day between the “psychological” and the “objective” novel, Maupassant took a hard objectivist line. For most of his career he was wary of looking too deeply into characters’ motivations. “The man who goes in for pure psychology can only substitute himself for all his characters,” Maupassant wrote, “for it is impossible for him to change his own organs, which are the only intermediaries between the outside world and ourselves.” Better, he thought, to report what people do and say, and say to themselves, than to ask what makes them tick.

And what a report we get in “Boule”—I read it a little less than a decade ago, and what stuck with me, more than any of the sexual politics, was Maupassant’s vivid descriptive powers. Surviving foremost in my mind was a paragraph about Cornudet, one of Boule de Suif’s companions—a total blowhard whose beard, I remembered, was the same color as the beer he liked to swill. I just revisited the passage and found it no less striking:

Then they took their places round a high soup tureen, from which issued an odor of cabbage. In spite of this coincidence, the supper was cheerful. The cider was good; the Loiseaus and the nuns drank it from motives of economy. The others ordered wine; Cornudet demanded beer. He had his own fashion of uncorking the bottle and making the beer foam, gazing at it as he inclined his glass and then raised it to a position between the lamp and his eye that he might judge of its color. When he drank, his great beard, which matched the color of his favorite beverage, seemed to tremble with affection; his eyes positively squinted in the endeavor not to lose sight of the beloved glass, and he looked for all the world as if he were fulfilling the only function for which he was born. He seemed to have established in his mind an affinity between the two great passions of his life—pale ale and revolution—and assuredly he could not taste the one without dreaming of the other.

It will come as no surprise, given the whiff of contempt emanating from those words, that Cornudet behaves like a complete prick in the story’s brutal conclusion, after Boule de Suif has done her duty. In a devastating, morose span of description, she finds herself shunned by the same crowd that urged her on, the same bunch whose liberation she’s secured. They’re all riding out on a stagecoach, and here comes Cornudet again:

Then Cornudet, who was digesting his eggs, stretched his long legs under the opposite seat, threw himself back, folded his arms, smiled like a man who had just thought of a good joke, and began to whistle the Marseillaise.

The faces of his neighbors clouded; the popular air evidently did not find favor with them; they grew nervous and irritable, and seemed ready to howl as a dog does at the sound of a barrel-organ. Cornudet saw the discomfort he was creating, and whistled the louder; sometimes he even hummed the words … and all the way to Dieppe, during the long, dreary hours of the journey, first in the gathering dusk, then in the thick darkness, raising his voice above the rumbling of the vehicle, Cornudet continued with fierce obstinacy his vengeful and monotonous whistling, forcing his weary and exasperated-hearers to follow the song from end to end, to recall every word of every line, as each was repeated over and over again with untiring persistency.

And Boule de Suif still wept, and sometimes a sob she could not restrain was heard in the darkness between two verses of the song.

A simple phrase like “digesting his eggs” conjures, in this sinister context, a mess of hideous gastrointestinal burbles. And how casually distressing to specify that Cornudet took the trouble to whistle more loudly against the noise of the coach, and that Boule de Suif’s sobs could be made out in the interstices.

Read all of “Boule de Suif” here, translated from the French.

Alfabeto Pittorico

Sploid, “a new blog about awesome stuff” (as opposed to the many blogs about unawesome stuff), drew my attention to Antonio Basoli’s Alfabeto Pittorico, a series of architectural-alphabetical engravings from 1839—twenty-four letters and an ampersand. (Sorry, J and W.) These are works of pure fabulism—Basoli, a painter and designer from Bologna, created sets and curtains for the theater, and his alphabet has a lot of stagecraft to it. Every letter looks like a scene from another play. Part of the fun is in wondering what compelled him to make these engravings at all: Was he on some kind of precursor to LSD? Had he been dissed by an illiterate architect, against whom he sought fanciful revenge? Did he need a novel pedagogical device to teach the ABC’s to his distracted children? Whatever his motive, he brought an impressive imagination to the table. His G, for instance, is built on a Viking ship with a rabbit at its bow; K appears to be in some sort of mosque, with people in prayer all around; S is carved into a treacherous cliff, at the foot of which is a grave with a mourner. S—the cruelest letter.

You can see the whole series here; if you’re thinking there’s an Alphabet City joke to be made, I regret to inform you that the editors at Sploid have beat you to it. I thought about closing this post by spelling out PARIS REVIEW in Basoli’s letters, but life is short, and I, like you, tire of clicking. So here’s TPR:

Stories We Tell

It’s a strange coincidence that I should think to look up Ruth Sawyer today. Last night, I mentioned her book Roller Skates to a friend—I thought her nine-year-old daughter might enjoy it—but I had no idea that August 5 was her birthday.

Sawyer died in 1970, at the age of ninety. As a young woman, she traveled to Cuba, where she worked in kindergartens established for orphans of the Spanish American War, training their teachers in how to tell stories. Upon returning to New York, Sawyer obtained a scholarship to study storytelling and folklore. She went to work telling stories in the city’s school system, working primarily with immigrant children, and later founded the NYPL’s first storytelling program. Throughout her career, she would travel around the world collecting folktales, and for many years she volunteered as a storyteller at a women’s prison. Her Way of the Storyteller, from 1942, is still regarded as a landmark text—one full of charm and interest for the layman, too.

The stories she learned and the people she met inspired several of her many children’s books. But the most famous, Roller Skates, which won the Newbery in 1937, was, frankly, autobiographical: The story of one year in the life of a well-to-do New York ten-year-old. Like her heroine, Lucinda Wyman, Ruth Sawyer also spent 1890 away from her parents, who were traveling. Far from resenting their absence, she found the time living in a boarding house to be one of adventure and discovery.

Like many of the best children’s protagonists, Lucinda is a bit of a black sheep: an independent-minded tomboy who would much rather roller-skate around Manhattan, get to know new people, and read Shakespeare than spend time with her ladylike cousins or French governess. Considered difficult and temperamental, she is in fact bursting with unexpressed affection. Indeed, given free reign for the first time, Lucinda’s openhearted curiosity allows her to make friends wherever she goes; in the course of the novel, she meets the poor family upstairs, the beat cop Mr. Gilligan, and the Italian boy, Tony, who runs the fruit stand. She has plenty of inspiring adventures—her puppet production of The Tempest stands out particularly—but the book is not without real sadness, even tragedy. Certain descriptions and stereotypes date it, but Sawyer’s compassion and broad-mindedness shine through, and it has aged well.

As in the cases of Harriet the Spy or From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, the character’s independence comes as the direct result of a sort of benign parental neglect, and the freedom that seems so magical to a young reader is not untouched by loneliness. Lucinda is ever aware that her idyll will end, that she will be expected to resume normal life, and, ultimately, to assume the responsibilities of adulthood. (In real life: shortly after this period, Sawyer’s father would die, leaving the family penniless; this latter period is chronicled in the more melancholy The Year of Jubilo.) Even knowing that the author—the character, in a way—would go on to a life of independence and adventure, it’s hard not to feel a pang at the passing of her childhood. To feel desperate, even. Here is how the book ends:

Today the skates sang a sorry rhythm. She’d never belong to herself again—not until she married and got herself a husband, and then she’d belong to him. Suppose she kept on skating in the Park for ever and ever! Never went back to the Misses Peters’ parlor, two flights up; never went to meet mama and papa with Aunt Emily tomorrow; never had another mam’selle. She could do it; she could do it, live like the lambs in the Park, be as free as air, never have tantrums, and she could cuddle all the babies in their prams. Her next birthday wasn’t far off. Somebody else could have it—could be eleven who wanted to. She didn’t.

She reached the reservoir and stopped, climbed the steps to the railing and looked into the still, placid water. Leaning over she could see her face reflected in it. She addressed herself solemnly: “Lucinda, how would you like to stay in the Park? How would you like to stay always ten? You could tell Tony and Uncle Earle, perhaps; and Mr. Gilligan. They’d keep the secret for you. Winter you would sleep with the bears in the caves and come out in the spring. Come out every single spring always ten years old, never any older. That’s what I’d call a perfectly elegant idea!”

Mad, Etc.

A panda painting, small-claims court, and the perils of communal living.

From a 1937 advertisement.

Of the many collectives in West Philadelphia, the Mitten was widely held to be the ideal model. Founded by six young progressives from the Inter-cooperative Council in Michigan, it hosted workshops on social justice and fundraised for local nonprofits. And it was a staple of the queer-arts scene: punk bands played in the basement and drag shows filled the living room, with performers grinding on audience members and audience members grinding on banisters. In the adjacent lot they had grown a lush garden with six raised beds and a chicken coop.

When I first moved to Philadelphia, I was eager to join a house like this one—but brimming with collaborative energy, they were in high demand, and the ones I found lacked the character and spirit that’d drawn me to communal living in the first place.

I was impatient, though, and took a room in Cedar Park, aka “University City,” at an A-frame Victorian with a huge mulberry tree. The quaint facade hardly matched its sterile interior: overhead lighting reflected off marble countertops, the white walls were bare, and there was La-Z-Boy furniture in suburban quantities. This collective included five members, young professionals who, surprisingly, spent the majority of time away from the house, staying often with their partners. A math teacher, a product engineer, a classical vocalist and a software designer—they were mild and even a little shy. But one of the members, Jeff, maintained a particular enthusiasm for the house. He spoke in an affectedly deep voice, noticeably straining as he described the order of things: regular meals “kept costs down”; adherence to the chore wheel “kept everything running smoothly.” He appeared to be the oldest by a significant difference; his skin had a jaundiced tint, and his goatee was visibly grayed. A baseball cap covered his bald head, and in his beige clothing he nearly blended with the plush chairs in the living room.

Wandering the house one morning, I noticed a decorative theme: a series of paintings in which different animals—horses, peacocks, pandas—were foregrounded by a green watercolor mist. Most of these hung in the hallway, but the one featuring pandas was leaned against the wall near the recycling bin. These pandas floated in a green haze, grazing and chewing at obligatory bamboo. The rightmost panda appeared to be returning from a pleasant jaunt, with a subtle smile forming in the corner of its mouth.

In the kitchen one afternoon, I found Jeff opening a bottle of San Pellegrino. “Hey, roomie, check this out,” he said, retrieving a bottle opener from the drawer and demonstrating a “fun fact”: women and men hold bottle openers differently, he explained, women by the handle and men by the head. “Funny, these … scientific differences between sexes,” he muttered, moving to the sink, where he ran hot water over the opener. “Gotta wash this now.”

Details of Jeff’s life seeped in sporadically through the thin walls. His software team, for instance, was struggling to find sponsors. As a result, he’d filed for unemployment. I often overheard him talking on the phone, complaining about the conditions of the house: cooking responsibilities had been ignored and silverware had been improperly washed. Later, I began to receive text messages about the caps on various condiments. “The olive oil was loose. I almost spilled it all over,” he wrote, “mad, etc … ”

The collective’s atmosphere was tense, so I struck up a friendship with my neighbor, Hannah, who wore pencil skirts and had big frizzy, flowing hair. She’d invite me in for whiskey, poking me hard in the sternum for emphasis. On Halloween, she invited me to a costume party and came over beforehand to paint my face. She asked how I was finding the house. “It’s okay,” I said. “But it would be nice to decorate a little more.”

I must’ve had one too many whiskeys—moments later we were dragging the panda painting out from behind the recycling bin. Using the paints in her bag, Hannah added a party hat to one panda and a monocle to another. The formerly grazing panda was made to eat a cupcake. Because I lacked artistic skill, she helped me give one of the pandas a convincingly dimensional party hat. I began to picture Jeff returning home and, discovering the alterations, flying into a rage, so I hid the painting behind the door to my room.

The disappearance of the painting went unnoticed for six months. Siting at my desk one Sunday, I heard heavy footsteps coming toward my room. In walked Jeff with two scowling police officers, their sleeves rolled back to reveal thick, faded tattoos. The door was pushed aside to reveal the dusty, nearly forgotten pandas. The first officer observed the painting with a furrowed brow. “Party hat wasn’t on there before?”

“No, officer,” Jeff confirmed, “no, it wasn’t.”

The smaller, mustachioed officer interrogated me. “When was this painting damaged?”

I thought about it. “Six months ago?”

The officers turned to Jeff. “And you’re calling us now?”

Jeff clenched his jaw in impotent rage. He barked at the officers to do their jobs.

“Sir,” they said, “you better calm down and talk to us outside.”

Outside, another police vehicle arrived. Jeff had called for the sheriff, a short, frog-faced man with a protruding stomach. “I want your badge number!” he yelled from the porch.

Displeasure swept over the sheriff’s face, down to the loose skin gathered around his collar. “You know, I don’t like it when someone asks for my badge number, because it usually means they’re gonna complain about me. Now, I’m already in a bad mood because you wasted their time”—the two officers held their belts in austere, identical postures—“and now you’re wasting mine.”

Jeff insisted that the necessary evidence was in my room. “Arrest him!” he demanded. But the sheriff explained that I wasn’t obligated to divulge any information. I could simply say the matter was “beyond my knowledge.” He turned to me and asked, “Who destroyed the painting?”

“That’s beyond my knowledge,” I said.

* * *

Later, Jeff attempted to explain the severity of my actions. Years ago, after months of courting, Jeff had finally convinced a special someone to join him for dinner at his favorite restaurant downtown, Kingdom of Vegetarians. They shared a mutual fondness for the decor: “We were … mystified by those paintings.” To commemorate the date, she made him a miniature replica of the pandas. After the relationship ended, Jeff struck up a deal to purchase the originals from the KoV owner.

Though the story didn’t exactly clarify matters, I understood that I had touched a nerve. Jeff gave me three options to rectify the situation. I could either (a) clean the painting myself; (b) take the painting to an appraiser and pay the estimated value; or (c) get my “artist friends” to create a new panda painting in the appropriate style.

I promised to pursue one of these routes, but my remorse ebbed with each passing week. I avoided Jeff while trying to move out as quickly as possible. We only crossed paths once, at which point I assured him that a near-perfect replica was on the way. Meanwhile, a room had finally opened at the Mitten, and I took it.

By the time I had settled into the Mitten, things were calm. I received occasional threatening emails from Jeff, but this problem was solved when I wrote a filter to trash them automatically. One morning, I found an envelope bearing the insignia of the court television show Judge Joe Brown. Inside, a letter addressed to me read, “You probably already know you’re being sued.”

One of the negatives of Jeff’s panda painting.

The next day, a thick bundle of papers came through the mail slot. Stapled together were accusations of vandalism, printed copies of email correspondence, and a lengthy appraisal from an arts conservator in Manayunk, who wrote that the painting’s “classic” style priced it at four thousand dollars. In the final pages were negative scans of each panda, the lush mist reduced to a dark void.

* * *

Hannah and I met at the downtown office of Community Legal Services, just above Wendy’s, its waiting room full of sullen faces. The director, Richard F—, read over my papers with an expression of sharp annoyance. “C’mon!” he said, waving me down the hall with a dismissive hand.

At his desk, surrounded by degrees and copious family photos, Richard’s initial surliness subsided into a relaxed humility. As I described the events, I omitted the details concerning my own alterations of the painting, instead focusing on the damage dealt by an unnamed “guest.” Richard encouraged this version of the story. “In no way should you be responsible for another party! All you have to say is one thing: prima facie,” he assured me,“the evidence is insufficient.” I mouthed prima facie silently as Richard reviewed the papers.

The following month I rose before a judge in small claims court, sweating profusely in a drab gray blazer. Jeff described his side of the case, regularly referring to me as a “vandal.” On this matter, it appeared that the judge wasn’t convinced, but I fell out of his favor when Jeff raised the issue of “house rules”—i.e., the rule against damaging property.

“Did you agree to this rule?” the judge asked.

Such a rule seemed to be common sense. “That’s a rule I generally follow…”

“Did you agree to this rule?” the judge repeated.

“But this is a rule that I follow in any case, I—”

“Yes or no?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, now, I am a fan of Antique Roadshow,” the judge said, “and there are quite a few diamonds in the rough out there.” For a moment he struggled to remember the details of an episode. Then he promptly ruled against me.

* * *

Richard was irate. “Appeal!” he said. “File it!” I did. Before the appeal date, the court encouraged us to meet with mediators. Though Richard was opposed, I thought the perspective might be helpful. Later that week, we found ourselves—Richard, Jeff, two UPenn law students, their professor, and myself—in a humid mediation room above the downtown municipal court. The professor observed from the corner while the rest of us gathered around a small table.

Jeff told his story, this time evoking even more sympathy—at several junctures in his retelling, the mediators sent appalled glances in my direction. Finally, he leaned forward with a threatening pulse in his brow. “Even if you successfully appeal,” he said, “I’ll just take you to a higher court. You’re going to pay for the damage.” This cold, stubborn statement was convincing enough. I was reeling. The little red spots atop Jeff’s bald head seemed to circulate. Richard called for a break.

“You shouldn’t pay anything!” he said as we stepped into the hallway. But I’d reached my limit. I resigned to draw up a settlement. When we returned, Jeff and the mediators were sharing snacks from the vending machine. A temporary praecipe was drawn up: I signed in agreement to pay a thousand dollars. Far worse than the monetary fine, though, was when Jeff extended a clammy hand my way. “Happy we can move on,” he croaked. Everyone huddled around as I put my hand into the grip.

I went straight to Hannah’s place, where we argued about fines and responsibility. We compared the artistic labor of party hats against cowboy hats. We cooled off, fought more, and then calmed down with a whiskey. The case had, I thought, instilled in me a more careful consideration of the objects in my environment. I would no longer make assumptions about property, even if it appeared abandoned. While settling into the Mitten, I took every opportunity to be conscientious.

But had I learned anything? Not long afterward, I was working with two of my most industrious housemates in the garden, painting the chicken coop, a task for which one of them loaned me a pair of boots. I caught the boot on an exposed nail, pulling the sole away from the base, and decided to fix it later and return it as though nothing had happened. It must have slipped my mind. I left the damaged boots in a shared closet for days until, one morning, I received a reminder on my door: a tube of shoe goo had been jammed through the small hole left by a missing doorknob. Just outside my room was the damaged boot, looking as though it had been flung angrily to the ground.

Timothy Leonido is a writer based in Philadelphia. Other work can be found in Gauss PDF, and is forthcoming in Triple Canopy and Lateral Addition.

History’s Greatest Typos, and Other News

Oops: in 2008, Chiie appeared in place of Chile on 1.5 million fifty-peso coins. Photo via io9

Virginia Woolf loathed the concept of the middlebrow—“If any human being, man, woman, dog, cat or half-crushed worm dares call me middlebrow … I will take my pen and stab him dead”—but she should’ve gone easier on it. “Middlebrow is a name you would never call yourself, but rather a semantic shoe that belongs on someone else’s foot. It is also, however, a workable synonym, in the sphere of art and culture, for democracy.”

Need a quick, cheap tutorial in plotting? Watch sitcoms without the jokes …

And while you’re working out your plot, you might want to avoid scenes set in restaurants. “That tense guy who ‘stabs his potato’ or ‘saws at his filet’ … I see what you’re doing there. Please don’t.”

Presenting Western history’s most seminal typos: There’s 1612’s “Thou shalt commit adultery,” and 1830’s Peeface instead of Preface, and the Chilean coin that misspelled Chile…

“What’s so great about adults? Classic-age Hollywood is full of movies for and about adults that are dull, stodgy, and uninventive—writerly and actorly, honoring traditional values with a secret whiff of piety and an eye on the cash box, rather Mantovani than Beethoven, rather Don Sebesky than John Coltrane. That kind of movie isn’t gone; it now occupies screens in art houses. It’s the rule to the exception.”

August 4, 2014

Birthday Suit

Not, here, in his birthday suit. Photo: Bohdan Paczowski

What did Śmieja say about me in the discussion in defense of my diary? “His brutality, egocentrism, and arrogance toward writers of lesser stature may be distressing … ”

But no! He misinterprets me! With me there are no “writers of lesser stature.” This again is a collective viewpoint. It is true that I sometimes demolish, with gusto, in jest, by attacking, writers, but only those who prance around in their epaulets. I have never really taken part in a single duel while clad in my stripes and epaulets; I have never written a single word dressed in anything but my birthday suit.

—Witold Gombrowicz, 1961, Diary

Witold Gombrowicz was born 110 years ago today. In 2012, the Daily published five excerpts from Gombrowicz’s Diary, widely considered his masterpiece. You can read them here.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers