The Paris Review's Blog, page 672

August 18, 2014

Its Light Was Prodigious

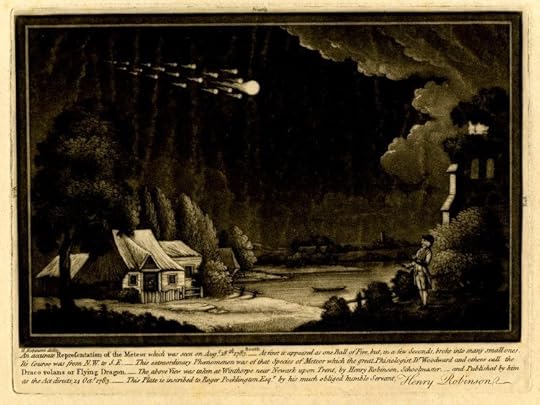

Paul Sandby, The 1783 Great Meteor, as seen from the East Angle of the North Terrace, Windsor Castle

As evidenced by its name, the 1783 Great Meteor was, yes, great and meteoric. At the time, not much else could be said about it with certainty—indeed, when it graced the skies of the British Isles 231 years ago today, it prompted a scientific (or pseudoscientific) crisis. Experts rushed to answer that burning—pun intended—question: What the hell was that?

On the night in question, Paul Sandby, a landscape painter, happened to be with Tiberius Cavallo, an Italian philosopher, hanging out on the terrace of Windsor Castle, enjoying the summer night, taking in the solemn spectacle of the sky, when, as Cavallo later wrote,

some flashes of lambent light, much like the aurora borealis, were first observed on the northern part of the heavens, which were soon perceived to proceed from a roundish luminous body, whose apparent diameter equaled half that of the moon, and almost stationary in the same point of the heavens … This ball at first appeared of a faint bluish light, perhaps from appearing just kindled, or from its appearing through the haziness; but it gradually increased its light, and soon began to move, at first ascending above the horizon in an oblique direction towards the east. Its course in this direction was very short, perhaps of five or six degrees; after which it directed its course towards the east … Its light was prodigious. Every object appeared very distinct; the whole face of the country, in that beautiful prospect before the terrace, being instantly illuminated.

I like the blend of specificity and awe here: Cavallo takes pains to describe the event as accurately as he can, but his account is suffused with the kind of wonder that only comes from confusion. How exciting it must’ve been, not knowing what was happening, not having the rote assurance of a scientific explanation. This was a time, after all, when one could still refer to the skies as “the heavens” without the slightest trace of irony.

In what amounts to an early example of crowdsourcing, artists and scientists came together to corroborate and dispute various accounts of the meteor. Sandby turned in an excellent watercolor of the phenomenon, and a schoolmaster named Henry Robinson made the engraving below. The meteor became the subject of wide speculation in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society; London Magazine ran an absurd account from a British lieutenant who claimed to have seen the meteor reverse its course, “moving back again, the contrary way to which it came.”

You Belong to the City

A still from 1986 Mets: A Year to Remember.

“1986 Mets: A Year to Remember is quite possibly the most amazing video yearbook for any professional sports team … ever.” That’s a comment from someone named the Wright Stache, who’s done God’s work by putting most of said video yearbook on Vimeo. But it could be anyone who grew up a Mets fan. There’s the series itself, of course—Game Six, Buckner, Jesse Orosco on the mound—but anyone with an ESPN subscription and a memory can tell you about that. A Year to Remember—known in our house simply as “The Mets Video”—is something different.

“I watched that video,” said a friend of mine recently. “I don’t really get what’s so great about it.” I didn’t even know how to respond to this. Is the Mets video tied up for me with my brother and my childhood and past glories and the pain of defeat and the entire nature of youth, life, and maybe death? Obviously. But it’s also pretty obvious that it’s just objectively awesome.

It’s an official Major League Baseball video; I remember that it came in a blue plastic case. Why we had it, I don’t know. I guess it was just what you did in the eighties. Because we weren’t the only ones; a bunch of my friends also owned it, and we can all recite the narration and replicate the “routine double play” from the play-offs and, of course, do a hotfoot in a pinch, as demonstrated by Roger McDowell and Howard Johnson. Indeed, the Mets video occupies a place of honor in a certain varietal of NYC psyche: for those of us who were really young in 1986, that long-ago triumph was symbolized by the video. And scored by Duran Duran.

I know I’m biased, but I really do think the Mets video has an excellent soundtrack. Certainly my brother agrees. But then, my brother—who, incidentally, has a tattoo of Mr. Met on his upper arm—has a special relationship with the film. When he was very little, he would don a Mets uniform in order to watch it. When he turned twenty-one, his college friends rented an auditorium and projected A Year to Remember on the big screen.

Today is my brother’s birthday, and in his honor, I bring you this clip—and defy any New Yorker with a beating heart not to cry.

Illinois Jesus

A forgotten Midwestern religious sect and the strange novel it inspired.

An illustration from Six Years in Heaven.

The most confusing thing about the rural Midwest is the importance placed on being normal. Perhaps this comes from demographic homogeneity: there’s a comforting stability in being able to drive a hundred miles in almost any direction and find a landscape almost identical to the one from which you set out.

The Midwest is construed as a place where nothing happens—that being, it should be emphasized, a good thing. Native Americans once lived here, of course; but there’s no longer any sign of them aside from some low mounds and their continuing near-universal use as school mascots. When I grew up here, no one wondered why they’d left. Probably it was more exciting somewhere else. Who could blame them? It’s a fine place to leave.

But on returning, as I did recently, the effect is disorienting: this is a place where everyone is cheerfully convinced of the rationality of their insanity. I was never immune to this. In school, everyone was perplexed by race problems. We weren’t racist. How could we be when there weren’t any black people? We ignored that in Rockford, Illinois, ten miles away, desegregation lawsuits were impossibly still grinding through the court system. Likewise, we firmly believed that gay people weren’t something we had; we learned we’d had a Jewish family in our town only after they’d safely escaped. This seems ludicrous to me now, and things have undoubtedly changed since the turn of the century. With the arrival of the Internet and cable TV, the boast that newscasters were carefully trained to speak like us—because we, among all Americans, had no accents—isn’t quite as impressive.

In 1988, when I was ten, my parents moved to a five-acre farm between the rust-belt city of Rockford and the village of Winnebago. Not being from the area, they were naturally curious about the history, and one of them found a Works Progress Administration history of Illinois in the library. In that book, we discovered that the country road we lived on had once not been so somnolent. A block north of us, a large complex of buildings painted red bore the name Weldon Farm, but once it had been called Heaven. In the 1880s it had been the center of an obscure religious sect—still lacking a Wikipedia entry of their own—called the Beekmanites. A woman named Dorinda Beekman had declared herself to be Jesus, as one did in those days; she died after promising to rise from the dead in three days. Her considerable followers were disappointed until one of them, a red-headed man named George Jacob Schweinfurth, neatly solved the problem by explaining that her spirit had moved into his body. Many agreed; he and his followers, the Church Triumphant, moved into Heaven and lived communally, where he’d attracted attention as far away as the New York Times.

A block south of my parents’ place, the road dead-ended in front of a run-down house. A “bad” family lived there, and their children occasionally went to school with me. We would have called them poor white trash had we not been afraid of being beaten up. Their house, ramshackle as it appeared to be, had a history as well: it had once been Hell. Schweinfurth had lived in luxury in Heaven, arrayed with young women called Angels. Their husbands, had they any, and members of the group who’d fallen out of favor, were sent to Hell, where the work needed to keep the sect fed was done.

The end of the Church Triumphant is predictable. The Angels started bearing children; this was declared to be a miracle, their fathers being the Holy Ghost, but the locals noticed that many were suspiciously red-haired. After too many Holy Ghost Children, Schweinfurth was arrested and driven from town. Later, he announced that he’d taken up Christian Science and moved to Chicago, where he became a realtor, thereafter vanishing from history.

The end of the Church Triumphant is predictable. The Angels started bearing children; this was declared to be a miracle, their fathers being the Holy Ghost, but the locals noticed that many were suspiciously red-haired. After too many Holy Ghost Children, Schweinfurth was arrested and driven from town. Later, he announced that he’d taken up Christian Science and moved to Chicago, where he became a realtor, thereafter vanishing from history.

I was surprised, at the time, that most of my classmates seemed entirely unfamiliar with this story. Schweinfurth’s cult was considerably more interesting than anything that seemed to have happened in Winnebago, Illinois, in the succeeding century. I came to realize I’d made a novice move: it was unseemly to be interested in local history. No one in the Midwest is familiar with the phrase “tall poppy syndrome,” but the idea, which can be traced from Herodotus, is abundantly familiar: those that stand out are cut down.

* * *

Every once in a while I search the Internet for Schweinfurth or Weldon Farm or Beekmanites. I don’t know what I’m looking for: maybe to make sense of the houses that held the place I grew up like distant and mismatched parentheses. What happened at Heaven and Hell is mostly beyond the reach of the Internet, of course, but surprising traces from the past pop up occasionally. Ongoing digitalization has worked its magic: first, a reference to a novel about Schweinfurth. Then, against all odds—the book seems to barely exist and I have never seen a copy—I received a badly scanned PDF courtesy of the Library of Congress. The full title alone indicates what the reader is in for: Six Years in Heaven: A True Story of Human Credulity and Unexampled Devotion, Embracing a Complete Expose Of the Abominable Practices and Monstrous Professions of George Jacob Schweinfurth, the False Christ, Whose Main Heaven is near Rockford, Illinois, with a Biographical Sketch of this most Remarkable Religious Pretender of the Century. The book is by one Alex. [sic.] McClenaghan, seemingly his only literary effort.

Six Years in Heaven is not a forgotten Midwestern masterpiece. It’s hard to say exactly what it is. Though the subtitle announces it “a true story,” it’s very much a novel. From the start, there’s a romance between a beautiful, impressionable young girl, Clara McCoy, and her devoted admirer, both from Shelbyville, Kentucky, who will be ensnared in the machinations of Schweinfurth in Rockford. Schweinfurth appears as himself, sometimes speaking in sourced quotations, and many of the supporting players—the members of the Weldon family, who gave Weldon Farm and my parents’ road its name, for example—do as well. Periodically the invented narrative breaks off and the reader is presented with events that seem more straightforwardly historical; sometimes even public documents are introduced into the text. The whole is illustrated, albeit not very skillfully, with depictions of climactic scenes. A figure of Satan—or at least a man dressed in a Satan suit—smiles behind the bearded Schweinfurth whenever he appears.

A man named Hatfield periodically turns up, trying to get to the bottom of the story of Clara McCoy and why she disappeared. (One can easily imagine McClenaghan at his study wondering what names people in Kentucky might have.) He is aided by various helpful pastors and once, intriguingly, a lady detective, whose part in the story is all too brief. They confer:

“This seems to be a chance for a story, founded on cold facts, that will discount Haggard’s wildest flights of imagination, if it does not rub shoulders with the alluring tales of the Arabian Nights.” “Truth is stranger than fiction,” laughed Miss Howard. “It assuredly is in this case,” he replied.

Despite Hatfield’s assurances, the question of veracity is left as a problem for the reader to solve. Clara is taken from her home by an apostle named Mamby who trawls the country selling histories of the Franco-Prussian War, keeping an eye out for beautiful women and rich elderly people who might be scammed. He, like Schweinfurth, is a master of mesmerism. Mamby appears to be as fictitious—he would find an easy home in the pages of Bram Stoker—as Clara. So does Dr. Brown, a doctor brought low by misfortune who takes refuge in Heaven and, through his skill in the black art of mesmerism, helps Schweinfurth raise the dead. (Mesmerism appears to be the chief source of Schweinfurth’s power, alongside his looking exactly like pictures of Jesus.)

Despite Hatfield’s assurances, the question of veracity is left as a problem for the reader to solve. Clara is taken from her home by an apostle named Mamby who trawls the country selling histories of the Franco-Prussian War, keeping an eye out for beautiful women and rich elderly people who might be scammed. He, like Schweinfurth, is a master of mesmerism. Mamby appears to be as fictitious—he would find an easy home in the pages of Bram Stoker—as Clara. So does Dr. Brown, a doctor brought low by misfortune who takes refuge in Heaven and, through his skill in the black art of mesmerism, helps Schweinfurth raise the dead. (Mesmerism appears to be the chief source of Schweinfurth’s power, alongside his looking exactly like pictures of Jesus.)

Six Years’s characters’ motivations are a mystery; they behave with a perplexing idiocy. Arthur Fitzroy, Clara’s betrothed, follows her from Kentucky to Rockford and goes undercover, working as a stable hand in Heaven for five years without catching sight of her, except for once, when he mistakes another woman for her. Then he leaves when Schweinfurth—whom, bear in mind, he still believes to be a swindler— explains to him that she’s left. The woman he mistakes for Clara gets consumption and is sent off to Clara’s parents’ house in Kentucky to die (the death of an Angel being unseemly in Heaven) in front of her parents, who don’t notice that their daughter has been swapped out.

Clara stays six years—with a brief escape—though she fails, from beginning to end, to believe in the immaculate conception of the Holy Ghost children, a central tenet of Heaven’s faith. The problem of motivation goes for Schweinfurth as well. He starts as an extremely religious young man, entirely noble until he proclaims himself the reincarnation of Dorinda Beekman and starts amassing land and followers. A follower attempts to explain:

Mr. Schweinfurth … is one of the most persecuted saints the world has ever seen. When a Methodist, they did not like him because he preached against sociables. He said he did not believe in having kitchens attached to churches.

Perhaps this is true. A minister from Rockford—who seems to be a historical figure—explains that he’s absolutely sure that Schweinfurth had no lusts of the flesh. Late in the book, when the congregation begins stirring, Schweinfurth announces his intention that his followers should be eunuchs, a promising development that goes nowhere, as does his sudden enthusiasm for pedigreed dogs “being valued at one thousand dollars each.” A description of Indiana fiddle-playing technique and tuning seems to have been included simply as padding.

The book is confusing because it was published in early 1894—the introduction is dated December 20, 1893—a year before Schweinfurth’s reign came to its ignominious end. He and the three leading Angels were arrested for adultery in April 1895. Fictionalization might have been a strategy to avoid libel, but that seems craftier than might be expected for a book whose final illustration depicts an elderly Schweinfurth being greeted by the devil at the gates of Hell. McClenaghan’s characters hope that public outcry will eventually bring down Heaven, but it seems more likely that Schweinfurth will be deposed by the more mundane problem of disposing of the bodies of his residents, who fall ill and die at the same rates that everyone else did in the nineteenth century—a troubling problem when they’d been assured they’d live forever.

Walking around the block the most recent time I was home, I was surprised to find that the dead end that leads to Hell had been blocked, the road torn up and overgrown with pigweed and St. Anne’s lace. The house, my mother said, had been torn down by the police; it had been abandoned for years. Drugs, the police thought. I mentioned that I’d found a novel about Schweinfurth, which surprised my mother. Why, I wondered, didn’t people talk more about what had happened there? What she heard, my mother said, was that Schweinfurth’s descendants were all over town; I’d gone to school with them. The whole thing was embarrassing.

To return to the New York Times article: Schweinfurth, we learn, was threatened by White Caps. The White Caps have also vanished from history, though not as inconsequentially as the Beekmanites. They were rural Midwestern predecessors of the KKK. Another story could be imagined here: Schweinfurth as a transgressor of cultural homogeneity who needed to be cleansed, the victim of religious persecution. One wonders how he would have told his own story, whether he might have been a freethinker rather than a rascal. Early in McClenaghan’s book, we see Schweinfurth as a fervently religious youth in Ohio, not far removed from Joseph Smith, to whom he is later compared. There are mentions made of Schweinfurth’s own versions of the Bible, though these don’t seem to have survived. We’re left with breathless news reports decrying the ignominy of Heaven and Hell and a novel that sells itself by being a true history, albeit with characters and a romance added. One wonders what the Angels would have said, whether they ever attempted to explain the wild years of their youth, years later when those who survived had settled down to sedate farm life: Did they believe they’d been tricked by a false Christ?

They, like Schweinfurth himself, have no voices left.

Dan Visel lives in Bangkok and is writing a book on reading.

Fabulous Prizes Await

R & R & TPR in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Chantal McStay

A reminder: through August 31, we’re having a #ReadEverywhere contest to celebrate our joint subscription deal with the London Review of Books. To enter, just post a photo of yourself reading The Paris Review or the London Review of Books on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook—use the #ReadEverywhere hashtag and one of our magazines’ handles. (Those of you who have already posted photos, fear not—your work is in the running.)

Our three favorite contestants will receive these jaw-droppingly swanky prize packages:

FIRST PRIZE ($500 value)

From The Paris Review: One vintage issue from every decade we’ve been around—that’s seven issues, total—curated by Lorin Stein.

And from the London Review of Books: A copy of Peter Campbell’s Artwork and an LRB cover print.

SECOND PRIZE ($100 value)

From TPR: A full-color, 47" x 35 1/2" poster of Helen Frankenthaler’s West Wind, part of our print series.

And from the LRB: Two books of entries from the LRB’s famed personals section, They Call Me Naughty Lola and Sexually, I’m More of a Switzerland.

THIRD PRIZE ($25 value)

From TPR: A copy of one of our Writers at Work anthologies.

And from the LRB: An LRB mug. (Never one to be outdone, the LRB is actually including a tote bag, some postcards, a pencil, and an issue with all of the prizes above. Retail value: inestimable.)

Hurry! August 31 is practically tomorrow, and this hashtag waits for no man.

The Erotics of Architecture, and Other News

Dig those curves: the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, in Rio de Janeiro. Photo: Rodrigo Soldon

In the summer of 2011, Phyllis Rose went to the New York Society Library and read one entire shelf of fiction—specifically, the shelf marked LEQ-LES. “In their obscurity, these books might be dull, bad or even unreadable; they might, in fact, be a total waste of her time. But she also felt certain that, should she embark on such a scheme, she would find herself on the readerly equivalent of virgin snow, for who else would have read this precise sequence of novels? … What followed was sometimes hard work and sometimes great fun. It was exasperating but also invigorating; deeply boring and yet surprisingly exciting.”

Congratulations to Louise Erdrich, who’s won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize’s distinguished achievement award. “The Dayton prizes are meant to recognize literature’s power to foster peace, social justice, and global understanding, and the distinguished achievement award is given for body of work.”

“You can’t kill e-mail! It’s the cockroach of the Internet, and I mean that as a compliment. This resilience is a good thing … E-mail is actually a tremendous, decentralized, open platform on which new, innovative things can and have been built … Yes, e-mail is exciting. Get excited!”

From “a guide to the sexual understanding of great buildings”: “Right angles don’t attract me. Nor straight, hard and inflexible lines created by man. What attracts me are free and sensual curves. The curves we find … in the body of the woman we love.”

It’s a radical act of self-reference. It’s a paradigm-shattering instance of recursion. It’s … the world’s most profoundly stupid sign, a sign whose sole purpose is to warn you against hitting your head on it.

August 15, 2014

Staff Picks: Desert Bus, Desert Islands, du Maurier

Desert Bus

Desert Bus (1995) has gained a reputation as the worst video game ever made, but as an act of culture jamming—and a comment on a medium that often panders to our basest fantasies—it’s probably the best video game ever made. Conceived by the illusionists Penn and Teller, of all people, and intended for release on the short-lived Sega CD console, Desert Bus never reached shelves, but its concept is so staggeringly mundane (“stupefyingly like reality,” as Penn Jillette puts it) that someone eventually saw fit to leak it. Your goal is to drive a bus from Tucson to Las Vegas: an eight-hour journey, conducted in real time. Is there any traffic to negotiate? No. Can you pause the game? No. Are there even passengers on the bus? No. Can you speed, at least? No. You can’t go any faster than forty-five miles an hour, and your bus always lists to the right, so you have to be vigilant in steering—no falling asleep at the wheel. If you veer off course, the bus will stall and you’ll have to wait for a tow truck to bring you back to Tucson, a humiliating defeat that also unfolds in real time. For the successful completion of this arduous journey, the player receives … one point. Then you get to make the return trip, another eight hours, for another point. Today, Desert Bus is available on smartphones for a mere ninety-nine cents, meaning it’s possible to drive the virtual bus from Tucson to Vegas while you’re on a real bus from Tucson to Vegas. The existential despair induced by such a pursuit may well sunder our universe—but it would be so cool. —Dan Piepenbring

Picking up a paper this morning, it suddenly struck me that Napoleon (whose 193rd birthday falls today) must be one of the few people who actually experienced that age-old question: “If you were stranded on a desert island, what would you read?” Confined to the (not quite desert) island of St. Helena, Napoleon’s top ten included Homer’s The Iliad, Milton’s Paradise Lost, and Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex. But according to his biographer, Vincent Cronin, Napoleon’s number one was Paul et Virginie, an eighteenth-century love story by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre in which the heroine is sent to be educated in France and (spoiler alert) drowns in a shipwreck on her way back to Mauritius. Napoleon allegedly loved anything that resonated with his own position—anything featuring, that is, an exile, a separation from a lover, or a life of confinement. How interesting that, in a situation that seems to cry out for the use of literature as escapism, he found release in books of captivity. —Helena Sutcliffe

Sadie Stein recently turned me on to Daphne du Maurier’s 1951 novel, My Cousin Rachel. As you might guess from the title, this later book shares certain ingredients with du Maurier’s 1938 blockbuster, Rebecca. There’s a grand estate in Cornwall, a suspicious death, an innocent orphan, and a femme fatale. In My Cousin Rachel, however, we get to meet the lady in question: a Cornish-Italian beauty with a shady past. Also, the orphan is a man, a twenty-four-year old virgin in love with the memory of his dead male cousin … who looked exactly like him. In Rebecca, du Maurier invented a genre—romantic suspense. My Cousin Rachel is a creepier, campier book. What makes both novels convincingly romantic, and actually suspenseful, isn’t their lurid plots, but how well du Maurier depicts the fear of abandonment. That’s what scares her protagonists—that they might lose the mysterious, dangerous love objects who have put them in touch with their own loneliness. As Sadie warned me, My Cousin Rachel is no Rebecca. But it’s close. —Lorin Stein

Some years ago, I bought a copy of The Song of Igor’s Campaign, translated by Bill Johnston, from Ugly Duckling Presse at the New York Art Book Fair, but I never got around to reading it until now. I wanted the chapbook for its content, but also for its materials. It’s a small, limited-edition letterpress booklet: the thick cotton cover, hand torn by Johnston, is covered with ink-blue birds in flight, a photolithograph by Yulya Deych; and the pages are bound with red cord. It’s more treasure than book, which is fitting for the story it holds. Composed sometime in the late twelfth century (though some claim the poem is a fabrication from the eighteenth century), the Song describes Prince Igor of Chernigov’s campaign, in 1185, against the nomadic Polovtsians, who roam the steppes. Things go poorly for Igor, but the tale overlays action sequences, both thrilling and terrible, with descriptions of the natural world, to stunning effect, as when Igor escapes from captivity:

Prince Igor leapt into the reeds

With the agility of an ermine,

Like a white duck into the wear.

Then he leapt up on his swift horse

And down again, running like the whitefoot wolf.

He hurtled towards the Donets meadows,

Soaring like a falcon beneath the mists,

Killing geese and slaying swans

For morning, noon, and evening meals.

—Nicole Rudick

I first came across Ring Lardner’s name in The Catcher in the Rye, wherein Holden says Lardner knocks him out. When I noticed Lardner mentioned again in Franny and Zooey, I picked up a copy of his collected short stories—I like to read my favorite writers’ favorite writers. A sportswriter by trade, Lardner has an impeccable ear for dialogue, and damn it, he can put a big brass button on a scene. He was revered by many Lost Generation greats—a young Hemingway wrote stories under the name Ring Lardner, Jr.—and there’s something classic in stories like “Alibi Ike” and “Mr. And Mrs. Fix-It”; it’s puzzling that they haven’t endured. In the hysterical “I Can’t Breathe,” we glimpse a precursor to a young woman like Salinger’s Muriel Glass through Lardner’s eighteen-year-old narrator: “And she says she was only engaged once while I have been engaged at least five times a year since I was fourteen, of course it really isn’t as bad as that and I have really only been really what I call engaged six times altogether, but is getting engaged my fault when they keep insisting and hammering at you and if you didn’t say yes they would never go home.” —Chantal McStay

Quivering with Pride

Edna Ferber

Today is Edna Ferber’s birthday. It’s funny, when you think about it, if you think about it. To the extent Ferber is talked about today, it’s as a member of the Algonquin Round Table. And yet, she was a best-selling author many times over. She won a Pulitzer in 1924 for So Big and saw that novel—along with Show Boat, Cimarron, and Giant—adapted for stage and screen. With George S. Kaufman, she collaborated on the plays The Royal Family, Dinner at Eight, and Stage Door—all subsequently made into films. In short, she was one of the more financially successful of that group of wits.

Writing in 1939’s A Peculiar Treasure, Ferber described the Round Table:

The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can’t imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition.

One wonders how they dealt with Ferber’s popularity. Her work was gently progressive—she often pointed up the hypocrisy and prejudice of the societies she portrayed—and characterized by strong women: widows, spinsters, abandoned wives. But they were also lush, old-fashioned, even soapy—anyone who’s seen Giant can attest to that—middlebrow novels, with the sales figures to prove it. For all the grandiosity of titles and themes, they were often domestic, too; settings and meals are given their due. One of the best and strangest moments in any movie, to my mind, occurs before the dramatic denouement of Dinner at Eight. In an aside, the cook unmolds a lion-shaped aspic onto a platter, and exclaims, “Look at you, quivering with pride!” This, alone, should have guaranteed her the plaque affixed to her onetime apartment building at 65th Street and Central Park West.

Her collaboration with the more overtly jaded George S. Kaufman made for a good study in contrasts. In his biography of Kaufman, Howard Teichmann wrote, “[Ferber] was small in physical stature, and a great believer in exercise. She had great personal courage, an overwhelming desire to travel, to seek new people, new places, new ideas. She did not have Kaufman’s wit, but she did have the ability to write rich, deep love scenes.”

She could also be difficult. Kaufman claimed to fear her temper, her scenes, her sensitivity, while she wrote, “When he needled you, it was like a cold knife that he stuck into your ribs. And he did it so fast, so quickly, you didn’t even see it go in. You only felt the pain.” Late in life, Kaufman wrote her, “I am an old man and not well. I have had two or three strokes already and I cannot afford another argument with you to finish my life. So I simply wish to end our friendship.” (In fact, they reconciled shortly before his death.)

Ferber also fell out, famously, with Alexander Woollcott. Following a series of petty, ego-wounding contretemps, she apparently described the critic as a “Jersey Nero who thinks his pinafore is a toga.” His response? “I don’t see why anyone should call a dog a bitch when there’s Edna Ferber around.”

Ferber never married—indeed, there is no record of a romantic relationship of any kind. She once said, “Being an old maid was a great deal like death by drowning—a really delightful sensation when you ceased struggling.”

Oneiric Architecture and Opium

Visualizing opium dreams through the etchings of Piranesi.

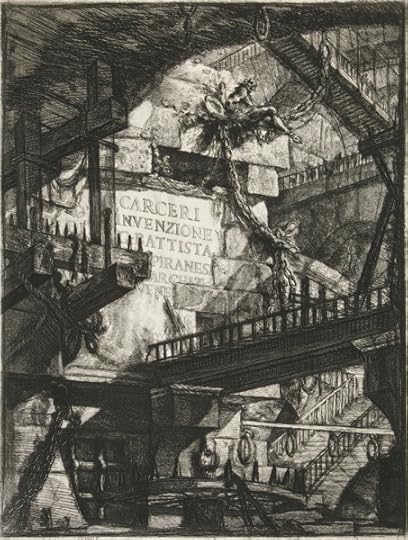

Title Plate

Prisoners on a Projecting Platform

The Arch with a Shell Ornamental

The Drawbridge

The Gothic Arch

The Man on the Rack

The Round Tower

The Smoking Fire

The Staircase with Trophies

It’s Thomas De Quincey’s birthday today—what better time to tour the mind-bending architecture of his laudanum-fueled dreams? The famed Romantic opium addict described his vivid dreams as “the immediate and proximate cause of my acutest suffering.” In his 1821 Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, he outlines their disturbing qualities. They’re extremely productive—pretty much anything he thinks about at night ends up in them; they resurrect deeply repressed memories from his childhood, accompanied by intense anxiety and melancholy, and they seem to expand time and space to the point of “unutterable infinity.”

What might this madness look like? Here De Quincey turns to ekphrasis, invoking Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons), a series of etchings that depict surreal, classical-inspired dungeons:

Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi’s, Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist, called his Dreams, and which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever. Some of them (I describe only from memory of Mr. Coleridge’s account) represented vast Gothic halls, on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery, wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, &c. &c., expressive of enormous power put forth and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls you perceived a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself: follow the stairs a little further and you perceive it come to a sudden and abrupt termination without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him who had reached the extremity except into the depths below. Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi, you suppose at least that his labours must in some way terminate here. But raise your eyes, and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived, but this time standing on the very brink of the abyss. Again elevate your eye, and a still more aerial flight of stairs is beheld, and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labours; and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall. With the same power of endless growth and self-reproduction did my architecture proceed in dreams. In the early stage of my malady the splendours of my dreams were indeed chiefly architectural; and I beheld such pomp of cities and palaces as was never yet beheld by the waking eye unless in the clouds.

Completed in the mid-eighteenth century, Piranesi’s Prisons, with their vast cavernous archways and creeping staircases, remind of the impossible constructions of M. C. Escher, though Piranesi precedes Escher by nearly two hundred years. And there’s an expressiveness to Piranesi’s line, a level of permitted imprecision radically different from Escher’s mathematically inspired print work—a certain nightmarishness, even. Through the Prisons, De Quincey manages to evoke the strange, haunting infinity of his dreams. And by setting these expansive dungeons in the mind of an addict, he gets at something key about the particular creepiness of Piranesi’s constructed prisons: the crush of infinity. There’s something claustrophobic about their sheer expansiveness. The shadowy inmates of imaginary prisons, like opium eaters, are enslaved in surplus, sentenced to learn the restrictive power of excess.

Chantal McStay studies English at Columbia University and is an intern at The Paris Review.

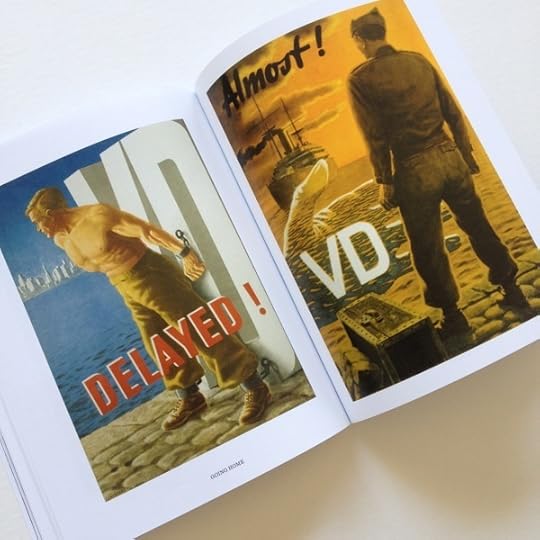

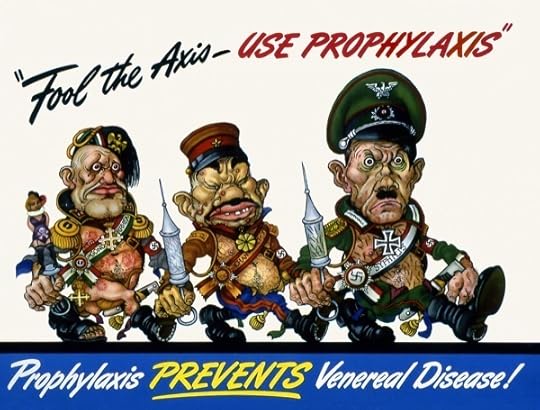

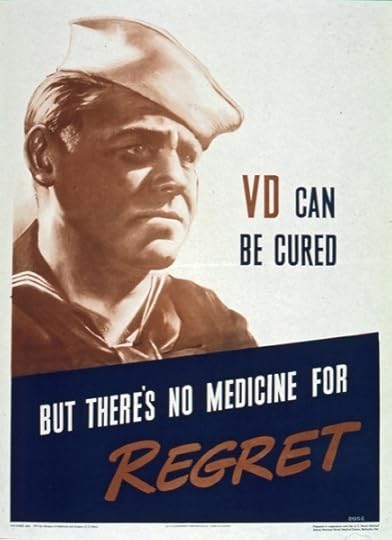

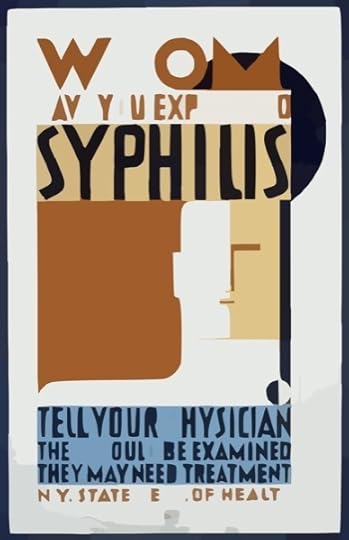

Protect Yourself

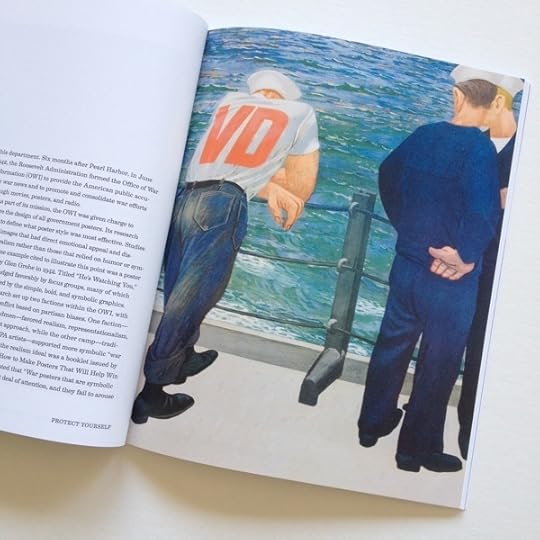

World War II’s sensational venereal disease posters.

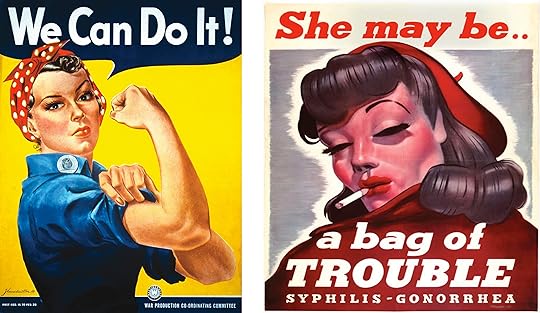

J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It!” woman first appeared in 1943, when he drew her in a poster for the War Advertising Council. Miller inadvertently created the most beloved character in the history of public service information: his bandanna-clad heroine—often misidentified as Rosie the Riveter, a separate creation of the WAC—has since been appropriated by innumerable causes as a symbol of solidarity, fortitude, and female empowerment. She’s ubiquitous among souvenir T-shirts, coffee mugs, and magnets. The “We Can Do It” woman survives in American culture as an emblem of all the social justice we want to see in World War II. But what became of her wicked stepsister, the “Bag of Trouble” girl?

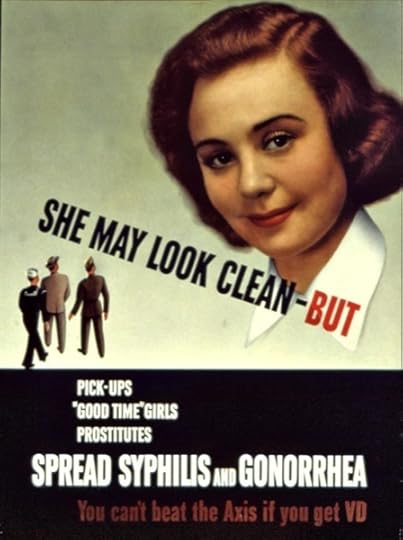

The “Bag of Trouble” girl appeared on her own poster in the same era—like her counterpart, she was beautiful and tough, with immaculate eyebrows and deep red lipstick, staring down her viewers with steely resolve. But the caption that surrounded her was more menacing than motivational: “She may be … a bag of TROUBLE.” Then, in smaller type, just in case you didn’t catch the drift: “Syphilis-Gonorrhea.”

If the “We Can Do It” woman represents World War II as the public wishes to remember it, then the “Bag of Trouble” girl represents the part that the public is eager to abandon. For that reason, the editor and archivist Ryan Mungia chose her for the cover of his new book, Protect Yourself: Venereal Disease Posters of World War II—the first piece of a much larger upcoming project of Mungia’s, Shore Leave, which documents the seamier side of the WWII experience through vernacular photos and paper ephemera. Seventy years after D-Day and the liberation of France, it’s no longer credible to memorialize the war solely with the romanticized combat of Saving Private Ryan and platitudes of the “Keep Calm and Carry On” variety. The war didn’t just traumatize the country—it exposed and exacerbated already disconcerting facets of American society.

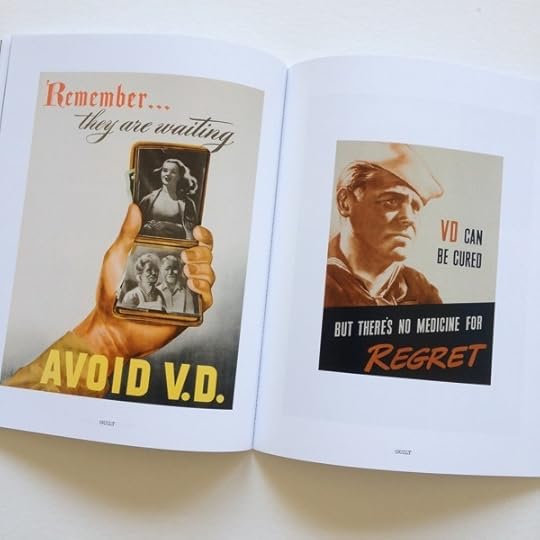

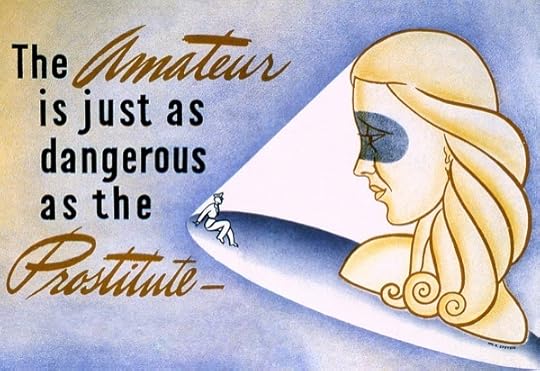

The posters scream for themselves. They were the product of antagonistic collaboration between the military, the Surgeon General’s office, and the War Advertising Council, a cabal of New York admen given the task of fine-tuning American propaganda. The near-schizophrenic variety of messages and graphics in this collection reflects the internal conflicts of the U.S. propaganda machine, which was trying to appease several different agendas simultaneously. Few of the posters in Protect Yourself are attributable to specific years, but the book makes it possible to trace multiple evolutions that unfolded during the war. The bold, abstract designs of the Work Projects Administration give way to the straightforward illustrative schemes of the WAC, which resemble advertisements from the pages of Fortune or the Saturday Evening Post. In the parade of captions, you can watch the morphing attitude toward sex education. What begin as concerns over public health—“Whom Have You Exposed To Syphilis? Tell Your Physician, They Should Be Examined; They May Need Treatment”—become manipulations of guilt and shame: “VD Can Be Cured But There’s No Medicine for REGRET.”

Mungia restored the posters from scans gathered at the National Archives, The National Library of Medicine, and the private collection of the graphic design historian Jim Heimann, who also contributes an introductory essay to the book. Many of these images have been bandied around the Internet for years, but they come to life on paper; the book affirms their role as lustrous and poisonous time capsules. Their twisted charisma comes not only from the shocking nature of the subject matter, but from the dissonance between message and medium. The posters are paragons of graphic design principle—but beneath their tidy exteriors are convulsions of pure lust and panic.

Propaganda craves the personification of an enemy for its goals. During World War II, the Axis powers were personified by Arthur Szyk’s grotesquely comic caricatures of Hitler and Hirohito, which stimulated contempt and hatred. Patriotism was personified by the sternly patriarchal figure of Uncle Sam, who impelled passersby to enlist, to donate, and to ration with one wave of his bony finger. The posters in Protect Yourself are cleverly organized by motivating theme to indicate the government’s restless search for an effective personification of sexual disease. They portrayed VD as a colleague of the Axis caricatures, and as the creeping specter of the grim reaper. They even made a series of posters in which the letters VD themselves are anthropomorphized, as if to invest a medical abbreviation with all the fear and ignominy once associated with Hester Prynne’s scarlet A. But none of these strategies was as arresting as the one that became the hallmark of the anti-VD campaign: the personification of sexual disease as the secret weapon of womankind.

The military insisted that VD was mainly a symptom of prostitution, resulting in multifarious depictions of “Ladies of the Night.” Over the course of the war, the posters expanded the threat to include “pick-ups,” “good-time girls,” and “amateurs.” The escalating suspicion climaxed with the most famous VD poster of all, which showed the face of a doe-eyed teenager emblazoned with the tagline: “She May Look Clean—BUT.” This was no longer a campaign about disease control. Its message was blatant: any woman who displayed an inkling of sexual desire was to be viewed as a walking sickness, an enemy of the state, and a direct threat to manhood.

The audience for the posters consisted of males, many barely out of high school, most of whom had never been exposed to sex education of any kind. “We saw the most horrific film on the dangers of catching VD that you could imagine,” the pilot officer Ron Pottinger remembered in his memoir, A Soldier in the Cockpit. “Enough to put you off any thoughts about women for the duration, if not for life!”

There were films, too, such as Know For Sure (1941) and USS VD: Ship of Shame (1942), whose graphic depictions of diseased genitalia and persistent warnings of blindness, paralysis, and death left a bigger impression on most young servicemen than the accompanying posters. But seventy years later, the films come off as stilted and corny while the posters remain potent. While the films addressed the procedures of venereal disease, the posters diagrammed a diseased psychology. They disseminated misogyny, ignorance, and shame, fostering attitudes that took root in postwar culture, when all those servicemen returned home to start nuclear families with the women they had only recently been encouraged to spurn.

Like many of the works in Protect Yourself, the “Bag of Trouble” poster was signed only with a single name, “Christian,” one of several mononymous propaganda artists lost to history. It’s unlikely that that he—or maybe she, as artists like Dorothy Darling Fellnagel were responsible for some of the VD posters—intended the figure as anything more than another image of the tarnished female. But these posters contain so much that was unintended.

Contemporary viewers tend to see the “Bag of Trouble” girl as an icon of misogyny, but she becomes more interesting and ambiguous when presented without caption, which is how she appears on the cover of Protect Yourself. Unlike some of the other women in the posters, she doesn’t automatically read as the walking personification of disease. She is not the skull-faced specter of death in a dress, nor is she the innocent “booby trap” so beloved by the propagandists. Hers is not a ruined face but one of cynical wisdom. She looks out from the cover as if she can see past all the assumptions of her viewers, past the wreckage the war, to the darker outcomes of the machinery that made her.

Though the “Bag of Trouble” girl might never outgrow her infamy, younger generations will always find new ways to redefine old symbols. There’s an Etsy store currently selling buttons that use that face with a proud twist on the old caption: “Nothing But … A Bag of Trouble.” “I got this for my daughter and she loves it,” wrote one satisfied buyer in a review. “She collects buttons and says it’s one of her favorites.”

Protect Yourself ends with an unknown sailor’s souvenir portrait, one of only a few photographs in the collection. (Mungia is saving most of his photographic evidence for Shore Leave.) It shows a scrawny, sinewy man, his hands on his hips, posing shirtless in front of a feebly painted tropical backdrop. His arms are covered in tattoos, and a huge three-masted schooner is inked across his bony breastplate. He can’t be more than twenty. He looks hungrily at the camera with goofy, uncaged eyes, baring just a sliver of teeth, as if he’s waiting for the punch line to some incredibly lascivious but very dumb joke. It is an expression as astonishing and inscrutable as the one worn by the woman on the cover of the book. Between those two faces are the beginnings and endings of a thousand untold war stories.

Sam Sweet's new book is All Night Menu , a collection of lost heroes and miniature histories of Los Angeles.

The Changing Language of Menus, and Other News

Henri Brispot, Gourmand, 1928

Trend alert: “Dystopian fiction is passé now,” says Lois Lowry, the author of The Giver.

This blog post about life on a commercial whaling ship is kind of long, but boy, it’s a fucking masterpiece!

Is there a writer with a reputation more complicated than Martin Amis’s? “Amis occupies a really peculiar position in our national life. He is the object of envy, contempt, anger, disapproval, theatrical expressions of weariness—but also of fascination. Has there in living memory been a writer whom we (by which I mean the papers, mostly) so assiduously seek out for comment—we task him to review tennis, terrorism, pornography, the state of the nation—and whom we are then so keen to denounce as worthless? … It's as if, and in answer to some inchoate public need, we demand of Amis that he say things in public so we can all agree on what an ass he is.”

There’s a kind of brinksmanship at work in the language of menus, which use verbose descriptions to confer status to food. According to new research, “every increase of one letter in the average length of words describing a dish is associated with an increase of sixty-nine cents in the price of that dish.”

“The subject of fashion friendships is intriguing … I’m struck by two divergent realities—one conveyed by social media and one I know at close range. They are not one and the same, despite how a photo of two pals (or two enemies) might appear. Because the most meaningful stuff in fashion occurs in private places, and some degree of trust is vital to getting inside.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers