The Paris Review's Blog, page 682

July 21, 2014

But There Is a Quiet Car, David

A commuter train in 1974. (Note the absence of consumer electronics.)

There was some trouble in paradise on the Ethan Allen Express. More than a few people around me were cursing the indifferent Wi-Fi as they desperately tried to remain tethered to the grid. Behind me, a passenger made serial phone calls in a mind-erasing loud voice. “I’m on the train!” he would always begin … We are all on that train, the one that left print behind, the one where we are constantly in real time, where we know a little about everything and nothing about anything, really. And there is no quiet car.

—David Carr, The New York Times, July 21, 2014

If you’re the Times’s senior media reporter, you need to stay connected 24/7, even when you’re on a leisurely train ride up the Hudson Valley.

But if you’re Joe Smartphone, always shouting “I’m on the train!” into your Samsung Galaxy S5, locking gazes with its oracular high-res screen straight from Grand Central to Poughkeepsie, here’s a tip. Power down and join the quiet car of the mind—the one that print didn’t leave behind—with a joint subscription to The Paris Review and The London Review of Books.

The Paris Review brings you the best new fiction, poetry, and interviews; The London Review of Books publishes the best cultural essays and long-form journalism. Now, for a limited time, you can get them both for one low price, anywhere in the world.

Knausgaard Truthers, and Other News

Just where does the hype end and the man begin?

Fact-checking the Knausgaard craze: Have Norwegian workplaces really instituted “Knausgaard-free days” in response to the success of My Struggle? The people demand the truth!

On clichés and their complications: “An expression is much more likely to be regarded as a cliché if it has typical or frequent use in contexts where it doesn’t apply very well (by being imprecise, misleading, or inaccurate, for example). Take the noun phrase best-kept secret … As a few examples will show, things that are dubbed best-kept secrets are in fact often not secret at all, and it is rarely specified, sometimes not even implied, in what sense they are ‘kept.’ ”

Remembering James Garner: “Garner wasn’t an actor who ‘reached,’ per se. He wasn’t doing accents or putting on prosthetics or trying to make himself over into someone he wasn’t. Movie and TV producers hired him to be James Garner.”

Is Amazon killing writing, or is it the market? “We are witnessing a bad Hollywood remake of a bad Hollywood remake of the Content Wars of the 1990s and 2000s … The plot remains the same: The traditional publishers of content defend their business models against the assault of the Internet. There’s some suspense, and then the Internet wins.”

Weird Al’s usage wars: “I purposely left a split infinitive at the end of my song … to be ironic, and also to see how many online grammar pedants it would annoy.” But then he didn’t realize that spastic is a slur in the UK …

July 18, 2014

What We’re Loving: Voyeurism, Privacy, the King of the Monkeys

An illustration from the Ramayana of Sugriva challenging Vali, ca. 1628–1649

God bless the anonymous German who published, in 1804, The Nightwatches of Bonaventura, a novel full of bizarre comic brio, pitched perfectly and awkwardly between Gothicism and Romanticism. Nightwatches is narrated by Kreuzgang, a poet manqué—and actor manqué, and even puppeteer manqué—who’s taken on a gig as a night watchman for a steady paycheck. He skulks about, muttering to the reader, warding off boredom by staring in people’s windows and riffing on the devil. All the while he seems to suffer from some kind of mood disorder; he’s acerbic where I expect him to be gentle, sententious where I expect him to be forgiving. As he observes, through curtains and windows, a succession of excommunications, thefts, murders, love affairs, and hauntings, Kreuzgang begins to charm with his lyrical cynicism. In his more aphoristic moments, he comments on our era as much as his own: “The character of the times is patched and pieced together like a fool’s coat,” he says, “and worst of all, the fool buttoned in it would like to appear serious…” There’s something perversely irresistible in Nightwatches’s voyeurism and its willful profanity. A new edition is coming in October; its publisher says it’s “one part Poe and one part Beckett,” which is apt, but I thought first of Tom Stoppard at his most playful. If he’d taken some bad LSD in the German countryside, he might’ve written this. —Dan Piepenbring

Some time ago, on their Tumblr, the Museum of Contemporary African Diaspora featured a conversation between James Baldwin and the incomparable Audre Lorde. Originally published in Essence in 1984, the conversation, in this iteration, opens with Baldwin’s comment “Du Bois believed in the American dream. So did Martin. So did Malcolm. So do I. So do you. That’s why we’re sitting here”—to which Lorde responds, “I don’t, honey. I’m sorry, I just can’t let that go past. Deep, deep, deep down I know that dream was never mine. And I wept and I cried and I fought and I stormed, but I just knew it.” It’s only the beginning of a vigorous exchange about Baldwin’s experience of being black in America, and Lorde’s of being black and a woman. During the women’s liberation movement in the seventies, black women fought on two fronts for equal rights, and Lorde is gloriously unrelenting on that fact. “Even worse than the nightmare is the blank,” she tells Baldwin. “And Black women are the blank.” —Nicole Rudick

For the first time in almost two hundred years, the Mewar Ramayana can be read and viewed as a complete work, thanks to the British Library’s digital reunification of the beautiful illustrated manuscript. The Mewar version of the great Hindu epic is distinguished by its richly saturated colors and its nonlinear depictions of the Prince Rama story; it was commissioned by Jagat Singh I of the Mewar dynasty in the seventeenth century. Today, the physical pages of the manuscript are divided between the British Library and several different collections in India, but the online project allows the work to be read in full, with a few lovely supplementary materials to boot. It’s that rare digital edition that succeeds by mostly staying out of the way: the focus is on the incredible hi-res images of the paintings and the original Sanskrit script, but there are also unobtrusive English descriptions (text and audio) and commentary from art historians to accompany each page. In one of my favorite illustrations, Rama helps Sugriva overthrow Bali to become king of the monkeys. Sugriva stands outside his brother’s pink confectionary palace, roaring “so that the very birds fall out of the sky in fright.” Rama puts an arrow through Bali, killing him. In the next panel, Rama sits jilted as the enthroned Sugriva, distracted by all the sex and wine that comes with being the monkey king, has forgotten about his greatest ally. So it goes. —Chantal McStay

When he battled insomnia a few years ago, Qatar’s Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad al-Thani “summoned a doctor to his palace. When the doctor arrived, he immediately saw the cause of Jassim’s sleeplessness—the rows of television sets covering the wall, all tuned to soccer day and night. Turn off some of your televisions, the doctor is said to have told him, and your insomnia will be cured.” That’s from the Times’s two-part series on Qatar’s ambition to become a global soccer power—they’re now set to host the 2022 World Cup, even though their population is a mere 1.8 million. (Let’s not get into the accusations of bribery.) The pieces are a fascinating look at what money can buy; they take us from the “dusty fields of Senegal and Kenya to the cloistered royal palaces of Qatar to a rundown stadium in a sleepy corner of rural Belgium” as Qatar searches for viable players to bring to its team. Only time will tell whether these international recruits will become Qatari citizens, but according to Andreas Bleicher, Qatar’s Aspire soccer program director, the “next World Cup will be ‘our’ World Cup.” —Justin Alvarez

A recent article in The New Yorker explored Virginia Woolf’s sense of privacy; a current exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery seemingly does away with Woolf’s privacy altogether, delving into every detail of her life and career. It includes portraits of Woolf by Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry; an array of letters, diaries, and photographs; and even the walking stick she left behind on that riverbank. Curated by Frances Spalding and unstintingly intimate, the exhibition provides rare insights into the genius of a woman who was largely an enigma. —Yasmin Roshanian

A Travel Tip

An 1854 French advertisement

Not too long ago, I was asked to contribute a travel tip to an article. I felt like a complete fraud, of course; my vacations, such as they were, consisted of the occasional bus visit to friends in D.C. and the odd weekend with my parents, heavy on historic sites. If I passed along any sort of “tip,” I risked conveying the impression that I was the sort of person who breezed through security with effortlessly straight hair, applied travel-size unguents in her seat, and, when she felt like napping, draped herself in an improbably large cashmere wrap. (This sort of person also had a roll for her jewelry, and had a pricey makeup bag that, in a pinch, could double as a clutch.)

I knew of no special hydrating sprays or extra-good earphones. I almost wrote, “Bring steak sandwiches,” since this is in fact something I like to do when I travel. But certain standards must be maintained. So I recommended wearing a new perfume when one goes on a trip.

I’m not advocating for the purchase of an expensive bottle every time you go to a cousin’s wedding. But for me, the act of dignifying a journey with its own scent can be enough to elevate a humble getaway to vacation status. It’s nice to find something that has a connection to wherever you are, but the actual perfume is secondary. The point is to create a sense memory for the experience that has, for you, no precedent. I’ve worn the same perfume since my twenty-third birthday, when I treated myself to my first bottle of En Passant, but from the moment I get in the cab to the airport, I like to wear something different, unfamiliar.

It should be a scent you can live with, of course, but it need not be one you love. I usually look for something inexpensive, in a travel roller; perfume samples are also perfect for this. I found an eau de toilette called Green Leaf in the LaGuardia terminal before leaving for this trip to Maine, and I have applied it religiously throughout my days here. Months later, I will be able to smell it and remember—or not, as the case may be.

I know it all sounds rather twee. “I wish we could see perfumes as well as smell them. I’m sure they would be very beautiful,” says Anne Shirley, in Anne of the Island, when she is at maximum insipidity, and everyone is in love with her, and everything she does is ethereal and enrapturing and the relatable, human Anne of Green Gables is a distant memory. Even by her standards, however, this is idiotic: a scent is a million times more transporting than an image. Stanislavski could have told her that. Because, really, that’s what it’s about, isn’t it? You’re creating a character: someone who travels, who’s capable of relaxation and maybe even adventure, and who—why not?—has an improbably large cashmere wrap in her bag. Or pretends to.

Local Business

I first noticed Harry Roseman’s art while dropping off my shirts at the dry cleaner near my home. It is a photograph of the wall in the dry cleaner on which the photograph hangs. Roseman had taken the picture because the sun had thrown on the wall the shadow of the shop’s neon sign. The name is spelled in outline on the drab wallpaper: Gladmore Cleaners. The picture hangs in the same spot where the shadow had fallen.

Then I noticed another one. Shirts under plastic covers and suspended from white, metal hangers form a line behind the register. Each shirt has a yellow slip attached to it. My own shirts hang there, ready for pickup. When the owner moves a section of shirts aside, a large photograph comes into view: a tight composition of the scene that has just been disturbed—all the shirts in their neat row.

Gladmore Cleaners in Poughkeepsie, in upstate New York, is owned by a Korean couple, Jongwon and Insoon Chung. In the recent past, Roseman has added their portraits to the collection in the store. High up above the counter is a photograph of the Chungs. They are standing at the counter, Insoon in more formal attire and without her glasses, Jongwon beside her wearing his customary white cotton vest.

This picture appears in another photograph of the Chungs taken by Roseman. The second picture hangs on the wooden wall beneath the counter where Insoon has her register. The scene is repeated here—the photographer and his subjects both keep their places from the first photograph—except that in the later picture, the Chungs are smiling and wearing brighter colors.

Roseman teaches at the same college where I am employed; I recognized his name when Insoon mentioned it, but knew nothing about his work. Later, I discovered that a sculpture I had seen countless times at JFK Airport’s Terminal 4—heavy, white clouds made from modified gypsum, billowing on a wall painted a deep shade of blue—was Roseman’s work. When I ran into him at the grocery store and mentioned that I liked his images at the dry cleaner, he told me that those photographs had been the starting point of a larger project on local businesses. Last year, Roseman was awarded a Guggenheim and so has been on sabbatical, but on a bright day in May, when my classes were over, we went around to all the other places where his pictures are displayed.

Roseman and his wife, the artist Catherine Murphy, live at the edge of Poughkeepsie on a large, wooded property where they have also built studios. Around the corner from their house, on Salt Point Turnpike, is Al’s Garage. For the past twenty years, Al Houghtaling has been Roseman’s mechanic. The walls of Al’s office are crowded with pictures of racing cars, trophies, signs informing customers on rates and general etiquette (“If you are grouchy, irritable, or just mean, there will be a $10 charge for putting up with you”). Amid this busy profusion of images is a large photograph that Roseman installed there. It shows an adjacent section of the store, with Al’s desk and chair and the flat-screen TV on the wall. There are other Roseman photographs in the office, and also among the steel tools and greasy auto parts in the repair bays outside. Each photograph reflects, with a tiny and subtle dislocation, the space that surrounds it.

Al told me that the photographs “get a lot of questions.” His customers are startled by them and ask what had prompted Al to take a picture of his office’s interior and hang it up there. Roseman is satisfied with this response; he says that by examining his photographs, people are likely to closely observe the surroundings as well. In this way, his pictures encourage looking. Roseman also said that his photographs are not supposed to appear to their viewers as art; they are ordinary objects, and they portray the everyday places of which they are a part. The impulse is celebratory, paying tribute to the people he interacts with, but his effort is nearly quotidian. Roseman says that once the project had taken shape in his mind, he thought of it simply as a record of “going about my business.”

In the antiseptic, even forbidding, coldness of the hallway that leads to his doctor’s offices, Roseman has put up a picture of the hallway itself. And inside, a few inches below the reception window, is a photograph of the very scene before you. The receptionist’s head of dark curly hair, which was visible to me behind the glass panel while she was on the phone, was in the picture, too. In each of the examining rooms, Roseman’s large images reproduce the small spaces: the medical diagrams, charts, and examining tables.

The photographs at other businesses repeat this pattern but with idiosyncratic differences. The photo-printing shop, On Location, which Roseman has frequented for years, and the art-supply store, Catskill Art, are both packed with photographs and frames, so Roseman’s images there blend into their surroundings. During a visit to one of his favorite restaurants, called Another Fork in the Road, in the nearby town of Milan, Roseman stepped into the bathroom and saw that a small decorative picture—of a red house with two chimneys—had fallen off its nail. The picture was sitting on the floor, against the wall. Roseman photographed this scene, and now his image hangs on the wall; the original image now resides permanently on the floor below. The restaurant’s chef and owner, Jamie Parry, says of Roseman’s photograph, “I have my own Baldessari.”

Parry’s comment reveals a formal appreciation of Roseman’s photographs. They are part puzzle, part visual joke, and coach us about ways of seeing. I saw virtue in Roseman’s own description of his images as public art, “low-key and gentle.”

Toward the end of the tour, Roseman and I went to LaGrange Physical Therapy (“Quality Care, Close to Home”). Roseman’s wife had received therapy there for several months, and a year ago, he had put up two of his pictures in their offices. However, Roseman immediately saw that the first picture wasn’t there. The wall next to the door was empty. He took me to the bathroom to show me the second picture, but that one was gone, too. I could see that Roseman was surprised, maybe even a bit shocked. A tall man named Fred came along, and Roseman pointed to the wall and asked him about the picture. Fred said, “John wanted it down. Do you want them back?”

Fred retrieved the photographs while we waited. The first one was a picture of the room where patients wait. It had the same frame photoshopped around it as the painting it depicted. In Roseman’s photograph, the painting—a nature scene, hills with trees turning fall colors, and in the distance, a river—appeared above an empty chair and a magazine rack. The painting was still hanging in its place on an adjacent wall. The owners had wanted to keep it, but not Roseman’s photograph.

In the car, I asked Roseman about it. He said that the painting was “wildly innocuous, but that was the one thing they thought to cherish.” He added that his wife had been happy with the therapy she received at the facility and would probably return if the problem resurfaced. Roseman said that he himself wouldn’t. It struck me that his project was really about relationships, the endlessly renewed transactions we have with the places where we do business. In the case of the therapist, that relationship had languished. My feelings were confirmed when I saw how Insoon was eager to tell Roseman about the changes in her life that had occurred in the time between the two photographs he had taken of her and Jongwon. She had tried to compose herself, she said, in the first picture: “I was very upset. My child was going through a breakdown. That is why I wasn’t smiling.” By the time the second picture was taken, the situation had changed: Insoon’s daughter had been admitted to MIT.

Amitava Kumar is the author, most recently, of A Matter of Rats: A Short Biography of Patna. He is professor of English at Vassar College.

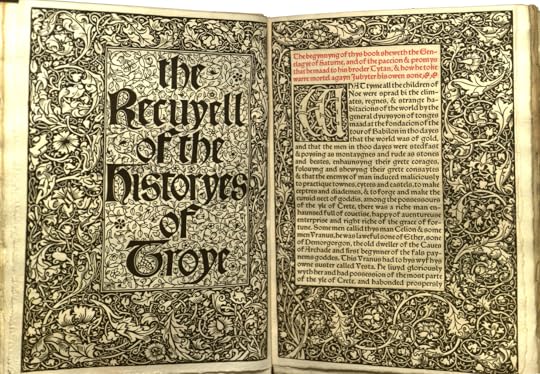

The Oldest Book in English, and Other News

The Recuyell of the Histories of Troye, the oldest printed book in English.

Javier Marías can think of seven reasons not to write novels, and only one reason to write them. (Fortunately, the one is pretty good.)

A 540-year-old book—the first to be printed in English—has sold at auction for more than a million pounds. “The Recuyell of the Histories of Troye is a version of a French book written around 1463 … The story is an epic romance which portrays the heroes of Greek mythology as chivalric figures.”

“I do own a pair of unusual books that I treasure … they are collections of poems, written by Howard Moss, poetry editor of The New Yorker from 1948 to 1987. They originally belonged to the poet May Swenson (1913–1989), who has been a favorite of mine since I stumbled on her “Half Sun, Half Sleep” in high school … Each is heavily underlined, in both pencil and ink—an emphatic, and ugly, green ink, seemingly more suited for some censorious schoolmistress than for Swenson, a nicely calibrated nature poet. Still, I take great pleasure in her scarring underscorings and in her occasional approving check mark or cryptic annotation.”

The Supreme Court has refused to hear an “emergency petition” from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s heirs, who are seeking “indefinite copyright protection” for Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson.

In which the novelist Scott Cheshire, an ex–Jehovah’s Witness, visits the Watchtower headquarters in Brooklyn: “I felt like throwing up, so I headed for the men’s room to pull myself together, pressed my face against the cold metal towel dispenser, and fainted.”

July 17, 2014

Soviet Ghosts

A military base in East Germany, constructed in 1937 and used by the Germans as an elite riding and driving school. Photo: Rebecca Litchfield, via the Guardian

The Guardian, Beautiful/Decay, and others have featured unnerving photos from Rebecca Litchfield’s Soviet Ghosts: The Soviet Union Abandoned: A Communist Empire in Decay, which documents the photographer’s travels to the ruins of the Soviet Union. The series examines how and why communities are abandoned, but this isn’t mere ruin porn; there’s an aspect of political subversion here, as Litchfield faced radiation exposure, arrest, and interrogation to secure these pictures, which include decommissioned locomotives, dilapidated military bases, and an abandoned sanatorium, many of them now deemed secret by the state. A more sensationalistic publisher might’ve subtitled the book, THE UNBELIEVABLE PHOTOGRAPHS THE FORMER USSR DOESN’T WANT YOU TO SEE! As Litchfield explains,

We maximized our stealthiness, ducking and diving into bushes and sneaking past sleeping security. But on day three, our good fortune ran out as we visited a top-secret radar installation. After walking through the forest, mosquitoes attacking us from all directions, we saw the radar and made our way toward it, but just meters away suddenly we were joined by military, and they weren’t happy …

See more photos here.

Rita Dove’s “Canary”

Billie Holiday and her dog Mister, New York, ca. June 1946. Photo: William P. Gottlieb

Billie Holiday died fifty-five years ago today. Many eminent American poets have elegized Holiday, attempting to capture something of her exquisite voice, whose unique tough-tender grain suggested a life of extremes. Langston Hughes’s “Song for Billie Holiday,” Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died,” and Rita Dove’s “Canary” are just a few of the diverse poetic responses to the loss of Lady Day; Kevin Young’s anthology Jazz Poems devotes an entire thoughtfully curated section, “Muting (for Billie Holiday),” to her memory.

These works belong to the larger tradition of the jazz elegy, a genre that attempts something next to impossible: to commemorate and preserve music that’s defined by its immediacy and transience. The grain of the voice. The physicality of the performer. The improvisations and flourishes and intangibles that exist for one night only. If the essence of jazz exists in the moment of performance, then much of the work of the jazz elegy is to make such music legible while also acknowledging the futility of such a project.

Rita Dove’s “Canary,” from 1989, begins:

Billie Holiday’s burned voice

had as many shadows as lights,

a mournful candelabra against a sleek piano,

the gardenia her signature under that ruined face.

I first came across “Canary” in Dove’s 1991 collection Grace Notes, which, as its title suggests, is full of poems that navigate the subtle intersection between word and sound, poetry and melody. I was struck by the Holiday elegy for its reverence—for its refusal to impose a tidy summation on the jazz figure. There’s no hint of the pathetic. Dove doesn’t try to capture Holiday—the image of the caged canary suggests that’s already been done by too many. Instead, she focuses on illuminating complexity, putting language to the strange sadness that flickers throughout Billy Holiday’s music.

The short poem evokes Holiday by insisting on the fugitive, the complex, and the fragmented; Dove conjures the depth and grain of Holiday’s voice, with its shadows and lights, and mobilizes it as a metaphor for a life of highs and lows. The poem shifts in verb tense and perspective, creating a kind of alternate timeline—stanzas meld the past and the present, reminding the reader of the web of intricate struggles behind the sob story that so often stands in place of Holiday’s life. The past is made up of a series of compiled immediacies—we remember the tragic narrative as easily as we forget the individual moments of practical need fulfillment and doing what “you have to.”

Dove presents Holiday’s aesthetic as one emerging from entrapment: Holiday, like a canary, sings through a cage, her personal truth boxed in by tabloid reconstructions and memory distortions. And Dove’s own tersely enigmatic poem formally embodies this constraint. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege / has been to sharpen love in the service of myth,” Dove writes, confronting the interplay of fact and legend in depicting the famous jazz singer. Holiday’s music proves that she’s a shrewd, masterful performer, but she’s burdened by a posthumous narrative that pins her as a tragedy, a beaten woman, an addict, a criminal, a prostitute. A poem like Dove’s allows us to see beyond these labels. The strongest weapon against being “invented” by others? Inscrutability. “If you can’t be free, be a mystery.”

The full text of the poem is available online through the Poetry Foundation.

Chantal McStay studies English at Columbia University and is an intern at The Paris Review.

Thinking of You

A postcard from Maine. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

When I was thirteen, and my dear friend Laura went on a teen hiking tour of the British Isles, I wrote her religiously. Letters, yes, but cards, too. I was stationary in New York, but I had found a lot of vintage postcards somewhere ,and sent a pair of fictional spinsters around the country on an imaginary road trip; each card chronicled their increasingly lurid and ridiculous adventures. One of the sisters proved man-crazy, the other developed a gambling addiction in Reno. When Laura transferred to a boarding school in Wales, their adventures continued.

Nowadays, that doesn’t seem like that big a deal. People are always sending Flat Stanleys and toys and gnomes around the world; you can download a template right from the Internet. Nothing new under the sun, I guess, but I loved having that imaginative connection to a friend across the world.

Now, as a grownup on vacation, I’m sitting here with a pile of postcards in front of me, wondering what to do about it. What, after all, is a postcard? In the age of e-mail and Instagram and Twitter, it’s a self-conscious anachronism. When you read an old postcard, their messages—in that spindly, legible, Palmer-script hand—are often strikingly banal. People really do say “wish you were here,” without embarrassment, and talk about the weather. With traditional postcards, the thought is what counts; these were, by and large, generic images bearing the most impersonal of greetings.

The modern postcard, paradoxically, takes some work. One must find stamps and mailboxes. And addresses are a problem: they are specific and important and not usually very close-at-hand. And there are few things more anticlimactic than having to secure someone’s address before surprising them with a mailing.

We still like to be thought of; of course we do. But now, an earnest view and a few inanities wouldn’t cut it. There has to be some element of self-conscious irony; the deliberate cheesiness of a classic vista, the weirdness of a subject, the cheery “wish you were here” sent from a site of carnage or tragedy.

I owe that dear friend a letter. I owe her much more than that. A dozen times I have started an e-mail, but I have never had the nerve to write. But being up here in Maine, where we first met—we both had A Tree Grows in Brooklyn on the shelves over our bunks at camp—I think of her all the time.

Perhaps that is the point, after all. Maybe I can re-animate those adventures. Maybe, sometimes, “Wish You Were Here” is actually enough.

Notes from the Milk Cave

Breastfeeding and boredom.

Detail from Stanisław Wyspiański’s Motherhood, 1902.

“You are an animal,” my husband told me. We were in bed. The context was not what you’d expect. A baby was latched onto my right breast while the left leaked an opalescent waterfall of milk.

“I’m a mammal,” I said. This is about as deep as our conversations got in the first month of parenthood. We were upstairs in what we have dubbed the milk cave—the dim bedroom of the nineteenth-century log cabin in southeastern Ohio, where we are currently living. I spend the better part of my days here, watching as my baby’s eager, sucking mouth goes rooting, and then latches on with the force of a heavy lid sealed shut on an overflowing container. There is nothing soft or gentle about my baby’s latch. It is the precise enactment of its definition: a clamping on, a fastening of two bodies. I feel a sudden tug of suction, a rasp of thirst, then sleepiness. I listen for the ker, ker, ker of her swallowing.

Before I gave birth, I knew breastfed babies needed to eat every two hours. But knowing this did not prepare me for the sheer amount of time breastfeeding would demand. Even if someone had told me “twenty minutes per breast per feeding,” it would still have taken sitting down every two hours for forty minutes for me to understand, because just like every other aspect of pregnancy and motherhood—morning sickness, contractions—the imagined experience turned out to be laughably unlike the experience itself.

I was hunkered down in the milk cave in a mess of sheets, sticky with an overabundance of milk, balancing the baby in the football hold and watching her eyes blink slowly open and closed with the rhythm of sucking. I’d finally finish, set her in her Baby Björn, and start digging into e-mails and then, again, she’d shove her fist in her mouth and start smacking her gums with comic franticness. Whole yellow and green summer days slipped by between the milk cave and the breezy porch, gazing at baby on the breast, at the whirring fan and the sheets with their pattern of roses, at the pastures of wavering grasses incandescent in afternoon light. Nights I awoke at two, at four, at six, and in the grainy coffee black, I’d hold the warm parcel of her, feel the eager pressure of those small gums, our animal bodies pressed together, the trickle of milk, the darkness undulating a bit in my delirium. I’d try not to fall asleep, have half-thoughts, then enter a space of no thoughts at all.

At first the novelty of the experience was enough to consume me entirely. But after a few weeks, I grew restless. I had to do something else. Or rather, I had to do something, since breastfeeding somehow didn’t count. It seemed to exist in that nowhere realm of feminine activity: in the back stairways, the dark kitchens, those places where women do the invisible work that drives and maintains life. The essential, ground-level work: the feeding, the nurturing, the staving off of chaos, work not measured in hours, miles, words, dollars. Work that doesn’t count as such. I would sit and stare and enter an oxytocin-fueled dream state, a new kind of boredom.

In the past, I’ve felt boredom as a restrained and tedious anticipation: How many more minutes in the waiting room, or until the bus arrives, or until this lecturer stops droning on? Boredom as a state of toe-tapping impatience for the next event. But in breastfeeding, boredom was a kind of presence, an altered way of being. It didn’t involve any anticipation. The act of giving milk itself is pleasant and soothing; it’s not that I am eager for it to end. And it’s not that it is uninteresting, between the strange palpable effects of the oxytocin and the mesmerizing face of the latched baby. It just doesn’t fit into the matrix of productivity or purpose or attention I’m accustomed to. It is simply being, mammal-animal being, layered with a human consciousness as thin and light as linen. It is not directed, not overtly constructive, containing the possibility of a spark of curiosity or desire, but also the possibility of a lack of either. There could be a revelation—an insight to be used in an essay or in dinner conversation—or there could be nothing more than the vaguest drifting of consciousness among the wind in the trees, a faint awareness of the sound Pattiann Rogers describes as a “cavalry of paper horses.” It is this lack of drive and intentionality, lack of self perhaps, that I find so unfamiliar and disconcerting. That I call boredom.

So I did what we do when we become bored: I bought an iPhone. The iPhone is incomparably handy for traveling and for taking six thousand photos of baby in hooded bath towels, baby in socks, baby in sweatpants, baby with flowers, baby with dogs, et cetera, but breastfeeding was the final justification: I needed a task to perform. And so at two A.M. I started writing one-handed e-mails, checking Twitter, googling Muriel Rukeyser. I got things done. I rejoined the ranks of multitaskers, not only living my life but cataloging and documenting it, too, making sure it adhered to measurable standards of productivity.

It only took about a week or so to recognize the loss behind this gain. The self I’d returned to—busy, hyperaware of a particular situation and its particular worth and where she is heading and why—felt more boring than the self present in milk and darkness. I couldn’t fall asleep again at three A.M., after the constant churning of Twitter. And each time I turned from the screen to my baby’s face, I felt guilty, as if I’d just missed a whole era for the forgettable pseudo-events taking place over and over in the spinning hamster wheel of cyberspace.

One night, as I was breastfeeding, checking e-mail on my phone, and thinking about this tension between presence and multitasking, I came across a recent post highlighting the work of the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, who emphasizes the importance of boredom in learning to pay attention to the world. Phillips writes:

In boredom, we can also say, there are two assumptions, two impossible options: there is something I desire, and there is nothing I desire. But which of the two assumptions, or beliefs, is disavowed is always ambiguous, and this ambiguity accounts, I think, for the curious paralysis of boredom … In boredom there is the lure of a possible object of desire, and the lure of the escape from desire, of its meaninglessness.

It is this in-betweenness that makes boredom so disconcerting. I’m staring out at the pastures, hypnotic in summer heat, their hazy grasses swaying, lulled by this escape from desire, its meaninglessness, and then a thought comes and I want equally to follow it and to let it go.

“‘When I’m bored,’” one “relentlessly cheerful child” explains to Phillips, “‘I don’t know myself.’” When I’m not writing, when I’m not multitasking, when I’m not consciously constructing new material, I don’t know myself. But in breastfeeding, I have found that not knowing myself brings its own satisfaction. Or perhaps it’s simply a way to be more present in the world at a time when just being without interpretation or justification or representation seems increasingly rare. The difficulty, I discover in writing, is in seeing boredom not as a gimmick, but rather as a state of being to be explored, productive or not productive.

In the midst of working through these thoughts, breastfeeding on the front porch one clear afternoon, I tasted a blackberry—that is, I didn’t just eat a blackberry expecting a blackberry taste. Looking out at the proscenium of summer sky over the humming stage of woods and pasture, I tended to think that maybe I’d just never paid so much attention. The blackberry had been just another layer in a multilayered reality. But when I spend the majority of my day sitting with a baby at my breast, with my world limited to a series of delicate, one-handed reaches and careful crab walks, my brain soft and dreamy with oxytocin, I notice only one flavor at a time, or I don’t consciously notice at all. I settle into my boredom as the day settles into its changing airs and clouds, until the baby pulls abruptly off the breast as she tends to do, sending a little jolt of pain through my nipple and leaning her head back in pure satisfaction, a dribble of milk running down her chin.

Sarah Menkedick divides her time between Mexico and a farm in southeastern Ohio. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Harper’s, Oxford American, The New Inquiry, Amazon's Kindle Singles, and elsewhere. She is the founder of Vela, an online magazine of nonfiction writing by women.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers