The Paris Review's Blog, page 697

June 6, 2014

The Last Word

Albert Goodwin, Apocalypse, 1902.

Late in 2007, a poet and programmer named Adam Parrish started @everyword, a Twitter account dedicated to tweeting all the words in English. The very first tweet, from 6:53 A.M. on September 2, 2007, seems to have been blasphemous, but after that came a, and things settled into a familiar alphabetical rhythm.

In the days of the early letters, we felt footloose and fancy-free. It seemed, for a while, that the dictionary and its roughly 109,000 entries would last us for the rest of our natural lives. Years passed. Words came and went at a stately pace. The most retweeted among them were sex and weed, those poles of the human condition.

But things took on a sudden urgency earlier this year when x, y, and z came around. None of us felt young anymore—we were living in the twilight of the alphabet, suddenly, acutely aware of our own mortality. @everyword, once a fixture of the Twittersphere, was soon to be snuffed out by Fate, as we all must be. As of this writing, zoril, zounds, and zoysia have just been tweeted, each one a harbinger of doom. The last word is expected to go up this weekend, if not later today. (One never knows exactly when Death’s cold, tenebrous hand will descend upon one’s shoulder.)

In an interview earlier this week, Parrish told The Guardian,

Whimsy is something that I'm very interested in evoking in people. I don’t like the concept of personalization on the web. When I get on the Internet it’s because I want to have a shared experience. I want to see what other people see. The Internet is a way to find out what life is like for other people. One of the goals of the stuff I make is to produce these experiences, and not sell you something, which is what a lot of the Internet is about these days.

Excellent points, but as the end beckons, whimsy is on the wane. (Or not—it was just tweeted a month ago.) Parrish never discussed why he chose to begin his series with blasphemous, but it augurs ill for us, now that we’re in the end-times. Has he been courting Satan with his word spells? Twitter’s eschatologists are predicting the apocalypse. What will happen when the final word goes up? Is there life after zed—or, more accurately, after zyxt?

Crazy Heroines Should Stay That Way, and Other News

No cures allowed. From the movie poster for I Never Promised You a Rose Garden.

It’s the fiftieth anniversary of Joanne Greenberg’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, a YA novel about her time as a schizophrenic teen. “Not long after I Never Promised You a Rose Garden became canonical, it also became a lightning rod … Greenberg claimed full recovery, and many psychiatric professionals worried that this would inspire a false and dangerous hope. Schizophrenics, they said, simply cannot recover.”

A new location (and ambiance) for Foyles, “London’s temple of books”: “Light streams down from rooftop windows on to a spacious white-walled atrium catching the edge of a 1930s dancefloor like a spotlight. It’s a huge change of scene for Foyles … which was once famed for dark forbidding bookshelves and a payment system so arcane that many visitors chose to steal rather than buy their favored paperback.”

Chester Nez, the last of the original Navajo code-talkers, has died at ninety-three.

What if it were your job to deliver bad news all day? You would succumb to a deep and enduring existential malaise, experts say.

“The best way to think about the universe is as a multidimensional space-time loaf.”

June 5, 2014

A Thing That Ends in Dying

Ivy Compton-Burnett

Happy birthday to Dame Ivy Compton-Burnett, who wrote dialogue so witty, lively, and fluent it makes Aaron Sorkin look like—uh—well, you get the idea—I’m sure one of them would be savvy enough to fill in the blank. “She was very, very clever,” Rebecca West said of Compton-Burnett in her 1981 Art of Fiction interview. “You’d have to be very tasteless not to see she had something unique to give her age.”

Here, in the way of proof positive, is the beginning of The Present and the Past, her 1953 novel, which starts with a lot of winsome talk about poultry, death, and cake.

“Oh, dear, oh, dear!” said Henry Clare.

His sister glanced in his direction.

“They are pecking the sick one. They are angry because it is ill.”

“Perhaps it is because they are anxious,” said Megan, looking at the hens in the hope of discerning this feeling.

“It will soon be dead,” said Henry, sitting on a log with his hands on his knees. “It must be having death-pangs now.”

Another member of the family was giving his attention to the fowls. He was earnestly thrusting cake through the wire for their entertainment. When he dropped a piece he picked it up and put it into his own mouth, as though it had been rendered unfit for poultry’s consumption. His elders appeared to view his attitude either in indifference or sympathy.

“What are death-pangs like?” said Henry, in another tone.

“I don’t know,” said his sister, keeping her eyes from the sufferer of them. “And I don’t think the hen is having them. It seems not to know anything.”

Henry was a tall, solid boy of eight, with rough, dark hair, pale, wide eyes, formless, infantine features, and something vulnerable about him that seemed inconsistent with himself. His sister, a year younger and smaller for her age, had narrower, deeper eyes, a regular, oval face, sudden, nervous movements, and something resistant in her that was again at variance with what was beneath.

Tobias at three had small, dark, busy eyes, a fluffy, colourless head, a face that changed with the weeks and evinced an uncertain charm, and a withdrawn expression consistent with his absorption in his own interests. He was still pushing crumbs through the wire when his shoulder was grasped by a hand above him.

“Wasting your cake on the hens! You know you were to eat it yourself.”

Toby continued his task as though unaware of interruption.

“Couldn’t one of you others have stopped him?”

The latter also seemed unaware of any break.

“Don’t do that,” said the nursemaid, seizing Toby’s arm so that he dropped the cake. “Didn’t you hear me speak?”

Toby still seemed not to do so. He retrieved the cake, took a bite himself and resumed his work.

“Don’t eat it now,” said Eliza. “Give it all to the hens.”

Toby followed the injunction, and she waited until the cake was gone.

“Now if I give you another piece, will you eat it?”

“Can we have another piece too?” said the other children, appearing to notice her for the first time.

She distributed the cake, and Toby turned to the wire, but when she pulled him away, stood eating contentedly.

“Soon be better now,” he said, with reference to the hen and his dealings with it.

“It didn’t get any cake,” said Henry. “The others had it all. They took it and then pecked the sick one. Oh, dear, oh, dear!”

“He did get some,” said Toby, looking from face to face for reassurance. “Toby gave it to him.”

He turned to inspect the position, which was now that the hens, no longer competing for crumbs, had transferred their activity to their disabled companion.

“Pecking him!” said Toby, moving from foot to foot. “Pecking him when he is ill! Fetch William. Fetch him.”

A pleasant, middle-aged man, known as the head gardener by virtue of his once having had subordinates, entered the run and transferred the hen to a separate coop.

“That is better, sir.”

“Call Toby ‘sir’,” said the latter, smiling to himself.

“She will be by herself now.”

“Sir,” supplied Toby.

“Will it get well?” said Henry. “I can’t say, sir.”

“Henry and Toby both ‘sir’,” said Toby. “Megan too.”

“No, I am not,” said his sister.

“Poor Megan, not ‘sir’!” said Toby, sadly.

“The last hen that was ill was put in a coop to die,” said Henry, resuming his seat and the mood it seemed to engender in him.

“Well, it died after it was there,” said Megan.

“That is better, miss,” said William.

“Miss,” said Toby, in a quiet, complex tone.

“They go away alone to die,” said Henry. “All birds do that, and a hen is a bird. But it can’t when it is shut in a coop. It can’t act according to its nature.”

“Perhaps it ought not to do a thing that ends in dying,” said Megan.

“Something in that, miss,” said William.

“Why do you stay by the fowls,” said Eliza, “when there is the garden for you to play in?”

“We are only allowed to play in part of it,” said Henry, as though giving an explanation.

“Oh, dear, oh, dear!” said Eliza, in perfunctory mimicry.

“William forgot to let out the hens,” said Megan, “and Toby would not leave them.”

Toby tried to propel some cake to the hen in the coop, failed and stood absorbed in the scramble of the others for it.

“All want one little crumb. Poor hens!”

“What did I tell you?” said Eliza, again grasping his arm.

He pulled it away and openly applied himself to inserting cake between the wires.

“Toby not eat it now,” he said in a dutiful tone.

“A good thing he does not have all his meals here,” said William.

“There is trouble wherever he has them,” said Eliza. “And the end is waste.”

The sick hen roused to life and flung itself against the coop in a frenzy to join the feast.

“It will kill itself,” said Henry. “No one will let it out.”

William did so and the hen rushed forth, cast itself into the fray, staggered and fell.

“It is dead,” said Henry, almost before this was the case.

“Poor hen fall down,” said Toby, in the tone of one who knew the experience. “But soon be well again.”

“Not in this world,” said William.

“Sir,” said Toby, to himself. “No, miss.”

“It won’t go to another world,” said Henry. “It was ill and pecked in this one, and it won’t have any other.”

“It was only pecked on its last day,” said Megan. “And everything is ill before it dies.”

“The last thing it felt was hunger, and that was not satisfied.”

“It did not know it would not be. It thought it would.”

“It did that, miss,” said William. “And it was dead before it knew.”

“There was no water in the coop,” said Henry, “and sick things are parched with thirst.”

“Walking on him,” said Toby, in a dubious tone.

“Eliza, the hens are walking on the dead one!” said Megan, in a voice that betrayed her.

“It is in their way, miss,” said William, giving a full account of the position.

Megan looked away from the hens, and Henry stood with his eyes on them. Toby let the matter leave his mind, or found that it did so.

“Now what is all this?” said another voice, as the head nurse appeared on the scene, and was led by some instinct to turn her eyes at once on Megan. “What is the matter with you all?”

“One of the hens has died,” said Eliza, in rapid summary. “Toby has given them his cake and hardly taken a mouthful. The other hens walked on the dead one and upset Miss Megan. Master Henry has one of his moods.”

Megan turned aside with a covert glance at William.

“Seeing the truth about things isn’t a mood,” said Henry.

The Unknown Ajax

Georgette Heyer

Like most families, mine makes frequent use of shorthand. In the case of me and my mother, much of the talk derives from the work of Georgette Heyer, the prolific author who created the genre of Regency Romance in the first half of the twentieth century. As my mother had, I read all of the books in my early teens, and even today, our exchanges are liberally peppered with the idiosyncratic language of Heyer’s novels—or, as she might put it, “Regency cant.”

Something popular is “all the crack.” Exaggeration becomes “doing it much too brown.” A young relative fresh from the sticks “needs a little town bronze.” A snob is “high in the instep.” And our favorite, of course, is “impervious to the most brutal snubs,” a phrase which one finds applicable with dismaying frequency.

Heyer was a famously scrupulous researcher with a vast archive of materials and detailed notes on all aspects of the eras she portrayed. (In addition to the Regency, Heyer set books in the Georgian and Medieval periods; she also wrote modern mysteries.) Her files contained subject headings like “Beauty, Colours, Dress, Hats, Household, Prices, and Shops.”

While devotees will argue passionately for their favorite Heyers (mine, not that you asked, are Cotillion, Devil’s Cub, and, of course, The Grand Sophy—I don’t like the May-December jaded-rakes ones) it can’t be denied that there are certain recurring tropes in her work. One biographer defined these as the “saturnine male lead, the marriage in danger, the extravagant wife, and the group of idle, entertaining young men.” To this I would add a mad chase at the book’s end, which oftentimes brings together disparate characters at a remote and random inn. But all are characterized by their real wit, fully realized characters, and utterly satisfying conclusions. (Okay, A Civil Contract, not so much.)

Heyer has been criticized in some quarters for the overwhelming barrage of period detail in her books, but it seems important to remember that in a time before a thousand and one Austen adaptations and the entire genre of “historicals” that Heyer invented, we had no mental image of this world. She had to recreate it from scratch, and she did. And the truth is, though we take it on faith that the Regency society she conjured is accurate in all respects—and I’m sure to the best of her ability, it was—she largely invented that world, and I’d imagine that many of her imitators have used her novels themselves as the basis of their research.

Heyer modeled her work on Jane Austen’s, and in creating her genre, she understood one very important thing: it is the framework of rules that makes these stories work. Social hierarchies, reputations, etiquette, a world governed by understood dicta—this is the framework on which to hang a story. Her books are tame by today’s standards—there is an occasional kiss, if that—but the stakes are real. By contrast, a modern historical will often take the trappings of costume drama—balls, country houses, servants, gaming hells—but allow its heroines to run wild at masked balls, stow away on pirate ships, and leap into bed with whatever duke takes their fancy. It’s not just that this sort of thing is anachronistic (that’s obvious), it’s that it strips the setting of its pleasures.

Heyer herself took a rather dimmer view of the enterprise. “I think myself I ought to be shot for writing such nonsense … But it’s unquestionably good escapist literature and I think I should rather like it if I were sitting in an air-raid shelter or recovering from flu.”

Croatia, a Work in Progress

Darijo Srna, Croatia’s captain and all-time most capped player. Photo: Fanny Schertzer, via Wikimedia Commons

Next Thursday, Croatia has the privilege of playing the World Cup’s opening match against Brazil, the host nation. The Eastern European country gets to take on a team that has won the World Cup a record five times—and is this year’s favorite—before nearly 70,000 people in São Paulo’s brand new Itaquerao stadium. The game is the first World Cup match to take place in Brazil since 1950, when the country last hosted the event. Brazil was the favorite that year, too, but it lost in the final in a shocking upset to Uruguay—and the country has never forgotten it.

Croatia, on the other hand, didn’t even become a nation until 1991. Its population of four and a half million is forty-five times smaller than Brazil’s. This World Cup is only its fourth appearance in five tries, and the team has had only two generations of players. It might seem that Croatia is absurdly overmatched. But you can also see the game as simply the next step in the development of their national soccer identity.

Croatia was born out of the violent dissolution of Yugoslavia, whose soccer team had made it to the semifinals and the quarterfinals of the World Cup twice; the team enjoyed a reputation as the Brazilians of European soccer. More than any of the other former Yugoslav republics, Croatia has continued that tradition, most notably at the 1998 World Cup, its first, where it shocked the world by finishing third.

That year, Croatia got a taste of what it’s like to face a host nation at a major tournament when it played its semifinal match against France in St.-Denis. Croatia’s star striker Davor Šuker, currently the president of its national soccer federation, scored the game’s first goal, just after halftime. “At that [moment] there were 80,000 people in St.-Denis and only a few thousand Croatians,” said Slaven Bilić, who played as a defender on that team and later coached the Croatian national team. “It was like when music is playing and someone comes in and presses the mute button.”

“Most people in Croatia remember that minute when we had the lead,” said Aleksandar Holiga, a soccer columnist for the news web site Tportal in Zagreb and the sports site Bleacher Report. “And then they remember when [midfielder] Zvonimir Boban, who was our captain and the most important player on the team, made a really bad defensive mistake that enabled France to equalize.”

Croatia had the lead for only a minute before France tied the game; the French team went on to win the match 2-1. Four days later, it won the World Cup. “Some people think it’s heavy madness that you think about that World Cup on a daily basis, and of course you don’t,” Bilić said on the phone from Istanbul, where he currently coaches the Turkish league team Beşiktaş. “But when I do think about it, I still feel that we could’ve won it.”

“Every generation since has been compared to that one,” Holiga said. “And it’s really unfair, because those players were extremely talented.”

Croatia made it to the World Cup in 2002 and 2006, but it didn’t make it out of the group stage either time, and it didn’t qualify in 2010. This year’s team struggled again in qualifying under its new coach, Igor Štimac, who played alongside Bilić on the 1998 team. Croatia won five of its first six matches, but then finished by losing three of its last four.

“It was okay when Štimac stuck to the tactics which were set before him by Bilić,” Holiga said. “But then he started to experiment, and he lost the faith of the locker room, of the media, of everybody.” Before the team’s final qualifying match, against Scotland, an online poll in the Croatian newspaper 24sata reported that ninety-eight percent of the public thought he should be fired. The team lost that match, too, 2-0. “The silver lining was that we won against Serbia,” Holiga says of an early qualifying match against the country’s bitter enemy from the Yugoslavian civil war.

“As much as you want it to be only a football game, it’s much more than that for the people back home,” said the midfielder Niko Kranjčar, whose father, Zlatko, not only captained the very first Croatian national team in 1991 but also preceded Bilić as national team coach. “Although both countries have moved on, the war is still quite fresh, and generations are still wounded.”

Croatia is currently under the leadership of manager Niko Kovač, forty-one, the former Croatian captain who was hired in October to coach the team through its two-legged playoff match against Iceland a month later. Born and raised in Germany, Kovač has his own vision for Croatian soccer. He regularly talks about translating his dual identity as a German and a Croatian to a team that has often been singled out for its passion and emotion. “I completely and totally embody the typical German virtues of thoroughness, orderliness, discipline, and organization,” he told FIFA.com in January. “We [Croats] are the kind of people who like a bit of spontaneity. Organization isn’t the be-all and end-all for us. I’m trying to instill the idea that some rules have to be kept.”

“He doesn’t shy away from stereotypes,” Holiga said.

The heart of Croatia’s team lies in its creativity, primarily in the midfield talents of Luka Modrić and Ivan Rakitić, both of whom play in Spain during the year, for Real Madrid and Sevilla, respectively. Its star striker, Mario Mandžukić, is suspended for the game against Brazil, but his absence opens up a spot on the team for two of the country’s most popular players, the forwards Eduardo, who was born in Brazil but came to Croatia at the age of sixteen, and thirty-four-year-old Ivica Olić, who will be playing in his third World Cup. “He’s one of those guys who the age doesn’t count,” Bilić said. “He’s like the red wine.”

Though lacking in the creativity of some of his teammates, Olić embodies the passion and the emotion of the stereotypical Croatian. “He’s this diehard character who is not really talented but who is trying his best every time,” Holiga said. “He runs up and down the pitch looking for every opportunity to be in the right place at the right time to just shove the ball in the goal. He has scored with his forehead, with his knee, with his heart—against Serbia, he scored with his badge. The ball hit him on the badge, so some people said that he scored with his heart.”

To face Brazil in São Paulo next week, Croatia will need that heart.

David Gendelman is research editor at Vanity Fair. Follow him on Twitter at @gendelmand.

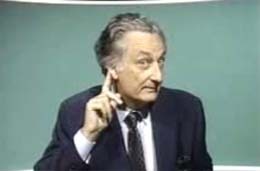

French in Action

Mourning Pierre Capretz.

“Robert,” in his ubiquitous Yale T-shirt, with the fetching “Mireille” in a still from French in Action.

I carry vivid memories of a boy named Robert, who insisted on wearing his horrible Yale T-shirt everywhere—to Chartres, to La Closerie des Lilas, to that seedy little rental-car hub on the Boulevard Périphérique, even (sacré bleu!) under a white blazer. What tone-deaf Ivy League foolishness, I remember thinking. The corollary bummer was that Robert wasn’t a caricature of the average American exchange student; he was more or less the ideal version thereof. He bopped through France, always encountering the lovely Mireille, who seemed to appear—without explanation or apology, and often without a bra—around the country’s every corner. And most important, he took every conceivable opportunity to improve his French. Robert was in Paris not to chase tail but to learn the language, to become a citoyen du monde. And yet he insisted on wearing that horrible Yale T-shirt everywhere …

Such were my first high school impressions, in 1999 and 2000, of the video pedagogy of French in Action, the language course cum TV series that taught me (and millions of other Americans) the rudiments of the Francophone lifestyle.

Pierre Capretz

French’s wild-haired emcee, Pierre Capretz, died earlier this year, in Aix-en-Provence, at eighty-nine. Capretz’s eyes always brimmed with mischievous possibility. He struck me as Henry Kissinger’s magnanimous French cousin, a man whom the world had weathered in the best possible way, imbuing him with wisdom and a philosophical cheer without which no one who teaches French in America can stay sane.

As I learned more about Capretz, I started to get the jokes, which, of course, included the Yale T-shirt that Robert seemed never to wash. My teacher-guru, Madame Demaray—a sanitization of de marais,“from the swamp”—had helped Capretz beta-test the program at Hotchkiss, a very swish prep school that had taken me in; it wasn’t terribly far from Yale, for which Hotchkiss’s founders hoped to groom their young men and eventually (thank God) their young women. Relations between the two schools were still cozy in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, and Mme. Demaray worked closely with Capretz as he developed his legendary regimen for the oral and aural teaching of French, imparting knowledge through a long-form video narrative that moved with the rhythms of a mystery novel. My teacher, with whom I was in half in love as one is with a glamorous great-aunt, told me in private about the million-plus dollars Capretz had gambled in making French in Action: about securing funding from the CPB and from WGBH in 1985, about the multiple heart attacks he suffered during the scripting, filming, and editing of part two. I saw my hispanoparlantes classmates toting Destinos and realized that the workbook/video/language-lab triad owed its current pedagogical vogue to Capretz, who believed, correctly, that the musical tools of language might succeed where 501 French Verbs had failed.

Capretz began his teaching career in 1949 in Florida, among the dead languages, and took his first job at Yale seven years later. His knowledge of Latin—in the same period when Derrida was commenting extensively on ancient texts—helps illuminate the tradition that he revived in French in Action. Until World War I, in the fancier schools, Latin was taught as something spoken and speakable, best accessed (especially in the realm of poetry) via tongue and ear. As a pioneer in multimedia learning, Capretz was also the preservationist of a much older pedagogical tradition, one that works remarkably well whether the language in question is alive or convalescing. Capretz’s fifty-two half-hour videos are camp in the best possible way, and deeply engaging. Professor Barry Lydgate, a Capretz friend and collaborator, notes the prescient democratic element in French in Action: it was “a giant Internet course, except it came out before the Internet,” he told the Yale Daily News, which also notes that French in Action remains “one of the top ten highest royalty revenue-generating licenses at Yale.”

In high school, after my sophomore teacher substituted Georges Simenon for Capretz and Commissaire Maigret for the young Robert, friends and I found the remaining tapes and finished the narrative in what would now be called binge-watching. Is “the man in black” good, or evil? Will Mireille fall for the Swede with the impressive quadriceps? Will she and Robert ever stop talking about Hemingway? All is answered in the final episodes, which present several very complicated verb constructions, including the dreaded passé simple, that I learned in spite of myself. Mystère et boules de gomme, as Capretz liked to intone: in loose translation, “all is riddles and gumballs.” The playfulness and wisdom of this idiom would be a fitting epitaph—a Capretzian wink to the millions he has welcomed to the monde francophone.

Ted Scheinman is a culture reporter based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He has written for Slate, the Oxford American Quarterly, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. His first book of nonfiction will appear via Faber later this year. Follow him on Twitter: @Ted_Scheinman.

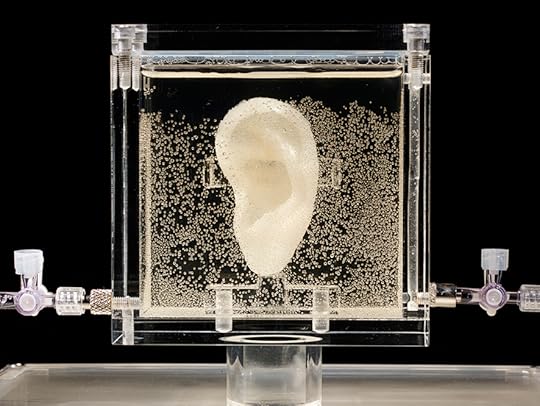

That’s Van Gogh’s Ear, and Other News

Photo: Diemut Strabe

Now on display at a German museum: a replica of one of Van Gogh’s ears. (Hint: it’s not the one he didn’t cut off.) “Created using 3D printers and genetic material from a living relative of van Gogh, it was shaped to be the exact size of the Dutch painter’s ear and is kept alive in a nourishing liquid.”

Yesterday’s usage wars were every bit as fraught and irrational as today’s: “‘Dilapidated’ was frowned upon by some because it comes from a Latin root, lapis, meaning stone, so it was thought that you should only refer to a dilapidated building if it was actually made out of stone … And it was considered that luncheon was the proper noun and that lunch was really only to be used as a verb.”

What chemical compounds produce the smells of new and old books? Vinyl acetate ethylene, alkyl ketene dimer, and 2-ethyl hexanol, of course!

Tales from New York’s bookstores: “One day a woman asked us which Jennifer Egan book she should read … We recommended Look at Me, and then suggested, ‘If you’d like it signed, Jennifer Egan is right next to you and is quite nice.’”

Centralia, Pennsylvania: still on fire. Has been since at least ’62.

June 4, 2014

No Memories

Tiananmen Square in 2007. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Today marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre. In 2009, The Paris Review published Liao Yiwu’s “Nineteen Days,” an essay in which he chronicles his imprisonment after the atrocity. He wasn’t there, but in his outrage he recorded a poem, which was enough to get him arrested for years. His piece is a haunting testament of a nation still struggling to reckon with the import of the event:

Three years after the massacre, I was in jail. Five years later, police were stationed in front of my house. Seven years later, there were sporadic memorial activities organized by individuals or small groups—petition letters, candlelight vigils, the burning of paper money to appease the dead, poetry readings, and hunger strikes. On the tenth anniversary, I repeated my poem “Massacre” for an overseas radio station by chanting and yelling into my telephone receiver … I remembered the story of Sun Jinxuan, a poet who died of lung cancer in late 2002. On June 4 that year, he woke up with pain. He called a dozen of his friends, most of whom were poets, writers, and celebrities. The first thing he asked on the phone was: “Do you know what day it is?” … Believe it or not, I was the only one who correctly pointed out the anniversary. Sun felt embarrassed and outraged by the answers of his friends. He yelled loudly on the phone, announcing that he intended to stage a one-person demonstration on the street. His slogan would be: “Killings, killings. No memories, no memories.”

In China, June 4 is also known as “Internet Maintenance Day”; authorities censor Weibo, a Chinese social network like Twitter, making it next to impossible for anyone to recognize or remark upon the political weight of the occasion. As a post on Language Log attests, the list of redacted words is remarkably thorough: even the usage of a simple word like today is enough to merit suppression. Subversive workarounds like “May 35,” a coded reference to June 4, are blocked, too, as are many others:

今天: today

89+(任意字符): 89+(any keyword)

廿五周年: twenty-fifth anniversary

致敬: pay respects

anniversary

viiv: Roman numerals for six and four, i.e. June 4th (“Six Four” 六四).

己巳月+乙未日: Jisi month+Yiwei day. In the traditional 60-year cycle, the first term is equivalent to May-June 1989, the second to a number of dates in the same year including June 4.

june 4

Jun+4th

6+4

63+1

65-1

六+四: six+four

六4: six4

6四: 6four

liusi: pinyin for “Six Four” (六四 Liù Sì)

bajiu: pinyin for “Eight Nine” (八九 Bā Jiǔ), i.e. 1989

陆肆: six four

陆四: six four

六肆: six four

捌玖: eight nine

捌九: eight nine

八玖: eight nine

六four: six FOUR (combination of Chinese character and English)

six四: SIX four (combination of character and English)

six+four

8的平方: square of 8, i.e. 64

八的平方: square of eight

祭奠: memorial ceremony

黑衫: black shirt

烛光: candlelight

维园: Victoria Park – a candlelight vigil for victims of the crackdown is held every year in Victoria Park, Hong Kong.

蜡烛: candle

平反: redress

tank man

TAM: short for Tiananmen

tiananmen

天安门: Tiananmen

广场: square

占占人: characters used as pictures to respresent a person standing in front of tanks

占占点: person being crushed by tanks

占点占: person being crushed by tanks

反官倒: oppose official profiteering

坦克: tank

戒严: impose martial law

学运: student movement

学潮: student strike

北京+屠城: Beijing+massacre all the inhabitants of a conquered city

丁子霖: Ding Zilin – Mother of a teenager killed on June 4th and founder of the organization Tiananmen Mothers.

邓屠夫: Deng The Butcher – i.e. Deng Xiaoping

胡耀邦: Hu Yaobang – Liberal Party leader whose death on April 8, 1989 sparked pro-democracy protests

赵紫阳: Zhao Ziyang – Hu’s successor as Party General Secretary. For his support of the student protesters, Zhao was purged from the Party and put under house arrest for the rest of his life.

袁木: Yuan Mu – State Council Information Office spokesman during the 1989 protests and apologist for the regime.

严家其: Yan Jiaqi – sociology student who went into exile in the US.

Of course, there’s no way to stop linguistic ingenuity, and users in China were quick to discover alternatives. “1-9-8-9” was among them, until the officials caught up; more creatively, someone uploaded an image of a poem that said: “Sail the ocean, sweep the square, clan king and eye field cannot be stopped!”

In Chinese, the characters for “clan king” resemble those for “democracy”; “eye field” looks roughly like “freedom.” The poem evaded detection.

“Nineteen Days” is available in its entirety online.

Menu Planning

Carl Bloch, In a Roman Osteria, 1866

The other day, having traveled to a midsize American city that shall remain nameless, my dining companion and I encountered the following description on an online restaurant menu:

Tender day boat scallops, lightly cajuned, pan seared with pancetta, caramelized leeks, sweet roasted red peppers, mint and pickled lentil medley, drizzled with a fava bean puree and organic pea shoots.

I was thrilled. I don’t mean that I wanted to eat it; there were like thirteen different components that I wouldn’t have wanted alone, let alone in combination. But I loved that the dish existed, in this moment in the world, in this place, and that, like a perfectly crafted poem, it managed to illuminate the human condition in a few deft strokes.

As the late Maya Angelou wrote, “The desire to reach for the stars is ambitious. The desire to reach hearts is wise.” Certainly, this dish was ambition incarnate—it was like the Macbeth of restaurant dishes—and certainly that was a big part of its appeal. There were seven parts (not counting seasonings) used, some ten different techniques employed, with more adjectives than you’d find in an Elizabeth Bishop poem.

Then there was the word “cajuned.” I had never heard this word used—in fact, with the exception of “Irishing up” a coffee, I had never heard of any ethnographic descriptor like this applied to food—but figured it meant something blackened and spicy in the manner of Paul Prudhomme.

The mishmash of buzzwords and techniques, things trying so hard to be sophisticated—it all sounded so unappetizing, so random. And yet, more thought and work had gone into the planning of that dish than most of us put into anything. The writing of that description had taken planning, and thought, and real effort.

Putting something into the world, in all earnestness, is scary. Your conception of beauty will never be everyone else’s, your sophistication may seem tasteless and dated to someone else. Maybe you are both right. I copied the menu description and, cruelly, sent it to my friends. I tried to work “lightly cajuned” into conversation, which is challenging. I tried to strip that collection of words of its unsettling power. But the menu won, in the end.

Welcome Our Writer-in-Residence

Courtesy of Yale University Press

We’re delighted to announce that Ansel Elkins will be our second Writer-in-Residence—and our first poet—at the Standard, East Village, in downtown Manhattan. She will be in residence for three weeks this July. We wish her a happy and productive stay.

Ansel is the recipient of a 2013 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the 2012 North American Review James Hearst Poetry Prize, the 2012 Fugue Poetry Prize, and the 2011 “Discovery”/Boston Review Poetry Prize. Her poems have appeared in AGNI, The Believer, Best New Poets, Ecotone, The Greensboro Review, Gulf Coast, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. She lives in North Carolina.

If you’re not familiar with our residency series: biannually in January and July, writers with books under contract are selected by The Paris Review and the Standard for a complimentary three-week stay at the newly refurbished Standard, East Village.

We also wish to congratulate our three finalists: Andrew Forsthoefel, Ken Kalfus, and Chinelo Okparanta, each of whom will receive two nights at the Standard, East Village. Because even writers sometimes need a weekend on the town.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers