The Paris Review's Blog, page 700

May 29, 2014

The Real Thing

The Coca-Cola Museum in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo: Melizabethi123, via Wikimedia Commons

On this day in 1886, the Georgia pharmacist John Pemberton placed his first advertisement for Coca-Cola, in The Atlanta Journal. The rest, as we say, is history. Painful history, in my case.

I don’t think my parents had anything special against Coke; we didn’t have it in the house, but then, we didn’t tend to have junk food around. We snacked on carrot sticks and yogurt; maple candy was a major treat. But I remember my dad drinking Coke on especially hot days, and I know “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” was part of his repertoire. For her part, my mom would reminisce about trying her first Coke—while, thrillingly, listening to Freddy “Boom-Boom” Cannon sing “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans”—when her paternal grandmother came for a visit from Arkansas. Coke still felt like freedom for her, the taste of the forbidden.

But for me, Coke for some reason became the enemy. I had always received positive reinforcement for being “unconventional” and hoeing my own row—what could be a better bugbear (I imagine my thinking went) than a soda that was not merely as an agent of tooth decay, but an opiate of the masses. In my mind, Coke was somehow tied up with everything I had dutifully internalized as “bad”: Sesame Street (which utilized advertising-style camera techniques and allegedly shortened attention spans), Amelia Bedelia (unchallenging), Cabbage Patch dolls (hideous), and sticker books (middlebrow). I wanted so badly to please.

Coke became my issue. What my parents had probably intended as merely a sop to oral hygiene quickly became, in my eager little hands, a self-righteous moral crusade. I shunned Coca-Cola with the zeal of a nineteenth century temperance advocate, and my sense of superiority was inviolate.

I became John Brown–like in my maddened conviction. At the age of eight, I formed, with a neighbor and my five-year-old brother, a club called the Coke-Haters (pronounced Coke-ader) Society. Because my neighbor was a year older, she was president; I was veep. My brother, who could not write, was secretary. The meetings, of which there were two, involved defiantly drinking juice and reciting our pledge:

I will never drink Coke.

This is what the first Coke-ater spoke.

As long as I am a member,

This is what I will always remember.

And then, one day, an opportunity for greatness arose: our suburban village’s annual Memorial Day Parade. We decided to make a float promoting our message, and there began a barrage of papier mâché-ing and painting and one serious fight in which the President said, about something, “Why don’t you cry about it, baby?” and of course I did exactly that, and ran home, and she had to come apologize after dinner. The float, once completed, was a magnificent thing: a Coke can the size of an old diaper holder, spewing bubble wrap carbonation and sporting a striped straw made from a pool noodle. The can was covered, on both sides, with large black paper X’s. I remember being slightly sorry to see the beautiful can so defaced, but we needed to get our point across.

The morning of the parade, we loaded the float into a red wagon and started down the hill toward Main Street. (If memory serves, no one had investigated either the parade’s starting location or its starting time; we were blithely sure we could join at any point and, given our just cause, be welcomed with open arms.) As the crowd thickened and we began to encounter people we knew, I saw the president’s resolve begin to waver. She looked furtive and uncomfortable. Finally, we came face to face with a group of other children.

“I’m not doing this, it’s stupid!” She said. “You pull the stupid float!”

“I can’t!” I said. “You’re this club’s president, and the president pulls the float!”

“Fine!” she returned. “You’re promoted!” And ducked into the crowd, leaving me holding the wagon’s handle.

I pulled the wagon determinedly forward and stationed myself on a corner, my parents observing from a distance. When a group of VFW oldsters came into view, I dragged my wagon into the fray and started to march, chanting,

Coca-Cola is an awful drink!

All the kids pour it down the sink!

Tastes like vinegar, looks like ink!

Coca-Cola is an awful drink!

I marched and I marched. It was probably just down Warburton and up a portion of Main, but it felt like forever. By the end, my voice was hoarse, my hands shaking, but I was triumphant. I had gotten our message across.

Not long after, the ex-President was seen, by me, drinking a Coke at the pool. And not long after that, to my chagrin, I was forced to break the oath, too. I was prone, in those days, to migraines that left me on my knees in front of my classroom’s miniature toilet and led to a call home. A new school nurse started dosing me with Coke syrup to settle my stomach, and even recommended my mother buy a bottle. The unfamiliar taste, magnified to the hundredth power in its evil-looking concentrate soon became associated with the blinding pain of headaches—and the inevitable sickness it failed to prevent.

But, humiliating though the episode was, I guess it did some good. Or, at least, positively impressed at least one grownup. I’ve only recently learned that during my stand, the mayor approached my dad and praised what she mistakenly believed was my contribution to the nascent War on Drugs.

Darwin’s Basket Cases, and Other News

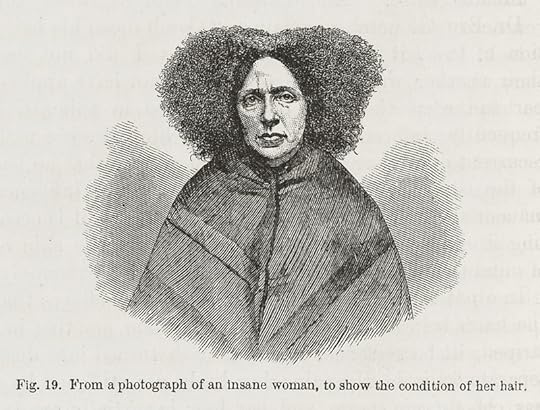

James Davis Cooper after a James Crichton-Browne photograph, Illustration from Chapter XIII of The Expression of the Emotions of Man and Animals; Insane Woman Showing the Condition of Her Hair, c. 1871-1872; image via the Public Domain Review

“It’s a curious thing to think of Charles Darwin sitting alone, closely studying photographic portraits of the afflicted and insane. But in the late 1860s, that’s exactly what he began doing: he sifted through portraits of kleptomaniacs, nymphomaniacs, sufferers of severe self-importance, hysteria, and general mania.”

Our very own Nicole Rudick on Bough Down, a new book of prose fragments and collage by Karen Green, who “faces a special difficulty: her husband was David Foster Wallace. This fact is both central to Bough Down and incidental to it. On the one hand, he was a famous, much admired writer, and Green’s new identity as ‘the designated survivor’ is one she can’t escape. ‘You are like the moon,’ she writes to Wallace, ‘you shed light on my insignificance from a great, wordless distance.’”

Charles Simic remembers the poet Russell Edson: “He thought of poetry as a cast-iron airplane that sporadically flies, chiefly because its pilot doesn’t seem to care if it does or does not.”

At the Library of Congress, 250 of Thomas Jefferson’s books are missing.

The Mesmerists of the eighteenth century believed that music played a vital role in the practice of Animal Magnetism. The proper tune could cure what ailed you, especially if it were played on one instrument in particular: the glass harmonica. “In fact, the association of the instrument with Mesmerism was one reason why it quickly went out of fashion.”

May 28, 2014

Etchings from Rembrandt

Rembrandt, Self Portrait in a Cap, Open-Mouthed, 1630

The Morgan Library has published a rich cache of Rembrandt’s etchings—nearly five hundred of them—in a new digital archive, a remarkable testament to his skills as a printmaker. (He was Rembrandt, after all.) The portraits are especially affecting: here are preachers, gold-weighers, printsellers, a woman having her nails trimmed, many men in exotic plumed caps. My personal favorite, above, is Self Portrait in a Cap, Open-Mouthed, from 1630: what a pleasure to see the Dutch Master himself, flummoxed, staring just over the viewer’s right shoulder, from a distance of many centuries.

Jitterbug Perfume

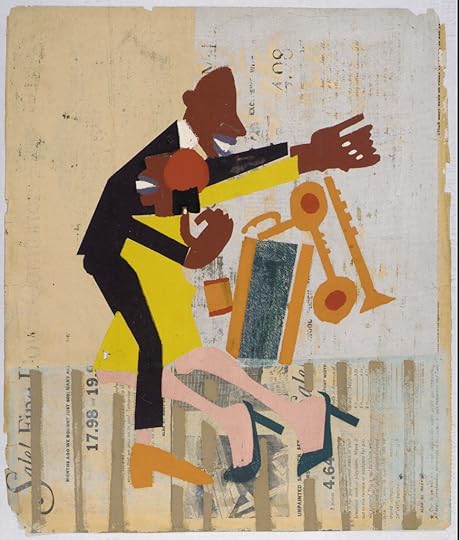

William H. Johnson, Jitterbugs (II), c. 1941

This week hundreds of passionate practitioners, armed with their passports and their dance shoes, have descended on the city where it started to celebrate the man who was one of its early creators.

“It has a universality,” said Cynthia R. Millman, who co-wrote a memoir with that man, Frankie Manning, who is revered for creating a gravity-defying move. “That’s why it was a phenomenon back in the day and why it’s a phenomenon today.”

—“A Celebration of the Lindy Hop’s Founder,” The New York Times

Like many people, I have no wish to revisit my high-school years. Although my experience was relatively benign and I have fond memories of the institution itself, I have deliberately hidden my yearbooks and was not tempted to attend this weekend’s reunion. That is why, for a long time, I avoided Irving Place.

Through most of high school, my set of friends—some five girls and four boys—and I spent every Sunday evening at Irving Plaza, swing dancing. This was in the late nineties, and the swing revival was in full effect, with Brian Setzer picking up Grammies and the Cherry Poppin’ Daddies getting semiregular air play. Even at the time, I found things about it sort of embarrassing—the cherry prints, the Swingers-style bowling shirts, the general L.A. cheesiness—but it was still a highlight of my week.

Back then, Irving Plaza, the deco-era theater off East Fifteenth Street, had not yet been renovated. It was splendidly gloomy, draped in mouldering red velvet and bedecked with a giant, 1930s mirror ball. My friends and I learned about its Sunday night swing concerts at the 92nd Street Y, where, on Saturday nights (at my instigation) we would sometimes attend the Argentine tango classes offered by a pair of octogenarians to a largely geriatric crowd. Probably someone told us that the Irving Plaza scene would be younger.

In fact, when we started going, we were among the youngest people at Irving; most of the crowd was made up of serious swing dancers who’d been doing the Lindy-Hop since long before the “revival.” These devotees were immediately identifiable by their two-toned swing-dancing shoes and, later, by their confident aerials. At first, it was a minor ordeal when a proficient dancer with Brylcreemed hair and wide-legged trousers up to his armpits would sidle up and commandingly present his hand for a dance; what followed was, one assumed, disappointment for him and trauma for me—being jerked and tossed around and risking treading on those confident, two-toned feet. Worst of all, because I was tiny—when we started, I had yet to begin my growth spurt, such as it was—people sometimes wanted to throw me.

Usually we danced with each other, or with a series of old men who showed up by themselves and ranged from creepy to benevolent. Somewhere in the middle was a gent whom we privately named “Uncle Leo” because he so strikingly resembled the Seinfeld character. Uncle Leo took a strong interest in our education, often dancing with us, or making pairs of us dance in front of him while he barked orders and criticism. “RELAX!” he’d scream, or, “HEAD UP—LIKE THERE’S A BALLOON ATTACHED TO IT!” or, least helpfully, “THE JOY OF DANCING IS ANTICIPATING WHAT YOUR PARTNER’S GOING TO DO NEXT!” In retrospect, this was all pretty good advice.

There was another regular—no nickname ever stuck, although he did look like the Yiddish star Hy Anzell. He would stand, motionless, face blank, and sort of dance us around himself while we tried to look game. It never seemed to occur to any of us that we could refuse.

A couple of my friends turned out to be really good dancers. One shy boy was a natural leader with great rhythm and a real gift for invention. My friend Anna had the confidence to follow any partner. And Elaine quickly picked up the intricacies of the line-dances, the “Shim-Sham Shimmy” and the “Jitterbug Stroll.” But after a few months, even the least coordinated of our group knew how to dance.

It didn’t dawn on me until years later how valuable a life-skill this was. Knowing how to dance is useful, sure, at but what I mean specifically is learning to follow. Ginger Rogers famously talked about the rigors of dancing backwards and in heels, but there are other, subtler challenges: those of putting your trust in another person’s judgment—or, at any rate, seeming to. And that is something that needs to be taught. The same skills can be learned in any number of ways—sports, theater, music—but rarely is it as direct and immediate as on a dance floor. (Maybe there’s more utility to the cotillion than I realized, growing up in a cotillion-deprived milieu.)

What were we looking for? Was it the theatricality of dressing up, or the big-band music? Certainly high school is a theatrical age, and my affectations tended to skew toward the sepia-toned. But I don’t think it was about some romanticized nostalgia: the scene was too immediate and frankly, too bizarre. It was freeing to be around all these weirdos.

Do I need to say that my friends and I were dorks? I don’t think so. That’s obvious. We didn’t even smuggle in drinks. When I look back at us, I know I ought to be embarrassed by the enthusiasm with which we threw ourselves into the enterprise, and the contrast to the lives of our cooler classmates. I’m sure they weren’t listening to Artie Shaw on their bedroom CD players, or wandering around in too-big vintage housedresses, let alone doing the Charleston with random old men. And yet, when I am honest, and go back to those days—or when I pass the marquee of Irving Plaza—I remember only the exhilaration and excitement of it. And I remember Uncle Leo’s advice—which, in fact, applies to most of life.

Maya Angelou, 1928–2014

Angelou in 2013. Photo: York College of Pennsylvania

There is, I hope, a thesis in my work: we may encounter many defeats, but we must not be defeated. That sounds goody-two-shoes, I know, but I believe that a diamond is the result of extreme pressure and time. Less time is crystal. Less than that is coal. Less than that is fossilized leaves. Less than that it’s just plain dirt. In all my work, in the movies I write, the lyrics, the poetry, the prose, the essays, I am saying that we may encounter many defeats—maybe it’s imperative that we encounter the defeats—but we are much stronger than we appear to be and maybe much better than we allow ourselves to be. Human beings are more alike than unalike. There’s no real mystique. Every human being, every Jew, Christian, backslider, Muslim, Shintoist, Zen Buddhist, atheist, agnostic, every human being wants a nice place to live, a good place for the children to go to school, healthy children, somebody to love, the courage, the unmitigated gall to accept love in return, someplace to party on Saturday or Sunday night, and someplace to perpetuate that God. There’s no mystique. None. And if I’m right in my work, that’s what my work says.

—Maya Angelou, the Art of Fiction No. 119

The Other Side of the Face

When I consider the neck, the first things that spring to mind are guillotines, beheadings, executions. Which does seem a little strange, since we live in a country where executions do not take place, there are no guillotines, and beheading is thus an entirely marginal phenomenon in the culture. Nevertheless, if I think neck, I think, chop it off.

This may simply be because the neck leads a hidden existence in the shadow of the face, that it never assumes a place of privilege in our thoughts about ourselves, and only enters the stage in these most extreme situations which, though they no longer occur in our part of the world, still proliferate in our midst, given the numerous decapitations in fiction. But I think it runs deeper than that. The neck is a vulnerable and exposed part of the body, perhaps the most vulnerable and exposed, and our experience of this is fundamental, even without a sword hanging over us. In this sense, it is related to the fear of snakes or crocodiles, which may as well appear in people living on the Finnmarksvidda plateau as in Central Africa, or for that matter, the fear of heights, which can lie dormant in people who have never seen anything other than plains and sand dunes, lowlands and swamps, fields and meadows.

Fear is archaic, it is embedded in the body, in its purest form untouchable to thought, and it is there to keep us alive. There are other vulnerable parts of the body, the heart being perhaps the most obvious, but when I think of the heart, I don’t think of it being pierced by a javelin or a spear or a bullet; that would be absurd. No, the heart fills me with thoughts of life and force, and if vulnerability and fear are involved, it is no more than a mild concern that one day it will simply stop beating. This must be because the heart belongs to the front of the body, the front we turn to the world, and always keep in check, since we can see what lies ahead of us, we can see what is coming, and take our precautions. The heart feels safe. That the neck is in fact just as safe, since we live in a world where people no longer carry swords, makes no difference to the feeling of vulnerability, it is archaic and closely linked to the fact that the neck belongs to the reverse side of the body, it is always turned toward what we cannot see and cannot control. The fear of everything we cannot see converges on the neck, and if in earlier times it used to be associated with physical violence, the most pressing association now is its figurative sense, which lives on in the social realm, in expressions like being attacked from the rear, getting it in the neck, watch your back, having eyes in the back of your head, being spoken about behind your back.

But the symbolic language that radiates from or the associations that converge on the neck, are not only about being struck, that is, being a passive victim of a surprise attack, or having something taken away from you, but also the opposite, where vulnerability is something that is offered. When we wish to show someone respect or to be polite, we bow to them, in other words, we expose our neck. It is a way of showing trust, and of giving something of yourself to the other, in an ancient system of differentiation where, in face of the supreme, you not only make a deep and sweeping bow, as to a king or other dignitaries, but kneel and lower your head to the ground, as you would before an altar or on a prayer mat. The gesture is humble, self-surrendering, it means laying your life in the hands of others.

While this country has not had the death penalty since the trials of Nazi collaborators after World War II, it is still applied in countries we have close ties to, namely the U.S.A., our main ally. If we consider the execution methods used there, it becomes obvious that death is not just death, since there is a big difference between separating the criminal’s head from his neck with a well-aimed stroke of the axe, and injecting his body with a lethal toxin or sending a surge of electricity through it. An injection has something neutral, controlled and professional about it, it is administered by a medical doctor, while electricity belongs to modernity and therefore seems civilized—though perhaps not so any longer, there is something crudely early modern about it, we associate it with quantity, with mass, and therefore also with the same kind of brutality and lack of sophistication shown by the errors of medical science during this era, lobotomy, measuring human skulls, eugenics. But still not as brutal as hanging, traditionally the least honorable form of execution, that most degrading to the victim—it is said that the prospect of being humiliated through hanging is what caused Göring to commit suicide in his Nürnberg cell—and even more so in the case of beheading. We perceive beheading as something barbaric and inhumane. To see a head being separated from a body must be one of the most terrifying sights a human being can be exposed to. But why? The end result is the same as when a lethal injection is administered, the person dies. It must be that something else is revealed in the act of decapitation, something more than the bare fact, the cessation of life functions. So what is it? In ritual sacrifice, which is still carried out in certain cultures, the head is separated from the body, and it is this, as much as death in itself, that the community gathers around. Death is displayed, and thus controlled, but the same would have been achieved if the victim had died quietly of poison.

While this country has not had the death penalty since the trials of Nazi collaborators after World War II, it is still applied in countries we have close ties to, namely the U.S.A., our main ally. If we consider the execution methods used there, it becomes obvious that death is not just death, since there is a big difference between separating the criminal’s head from his neck with a well-aimed stroke of the axe, and injecting his body with a lethal toxin or sending a surge of electricity through it. An injection has something neutral, controlled and professional about it, it is administered by a medical doctor, while electricity belongs to modernity and therefore seems civilized—though perhaps not so any longer, there is something crudely early modern about it, we associate it with quantity, with mass, and therefore also with the same kind of brutality and lack of sophistication shown by the errors of medical science during this era, lobotomy, measuring human skulls, eugenics. But still not as brutal as hanging, traditionally the least honorable form of execution, that most degrading to the victim—it is said that the prospect of being humiliated through hanging is what caused Göring to commit suicide in his Nürnberg cell—and even more so in the case of beheading. We perceive beheading as something barbaric and inhumane. To see a head being separated from a body must be one of the most terrifying sights a human being can be exposed to. But why? The end result is the same as when a lethal injection is administered, the person dies. It must be that something else is revealed in the act of decapitation, something more than the bare fact, the cessation of life functions. So what is it? In ritual sacrifice, which is still carried out in certain cultures, the head is separated from the body, and it is this, as much as death in itself, that the community gathers around. Death is displayed, and thus controlled, but the same would have been achieved if the victim had died quietly of poison.

When the French philosopher Georges Bataille founded the secret society Acéphale (The Headless) in 1936, which among other things celebrated the decapitation of Louis XVI and supposedly also discussed the possibility of carrying out a human sacrifice, the reason was not simply because the chop in the neck opened the abyss between life and death, but also between head and body, reason and chaos, human and animal, in a symbolic language where the neck forms the transition between what is low, corporeal-animal, and what is high, spiritual—but also in an ambiguous mythical language, where beheading reveals or liberates certain forces, murky and archaic, linked to death, soil, darkness, but also to repetition and continuity, for what the sacrificial victim exhibits, with its steaming blood and deep bellow, is a place where existence is dizzyingly densified. This is why Francis Ford Coppola ends his film Apocalypse Now with sacrifice and beheading, where meaning meets meaninglessness, life meets death, collective transgression meets individual limitation.

Having said that, the opposite way of thinking, which views beheading as the cutting off of an electrical cord, that is, a way of thinking that is instrumentalist and functionalist, is not just possible, but completely dominant in our time. We desire clarity, aspire to reason, reject the darkness, the uncertainties, the steaming blood. Few places express this more clearly than a hospital. In a hospital, the body is divided into departments. One department for the ear, nose and throat, one for the eyes, one for the stomach and the intestines, one for the sexual organs, one for heart and blood vessels, and one for the soul, which is treated in the psychiatric wards. This is of course the case because medical science is instrumental, it has analyzed the functions of the different body parts and organs, and seeks to restore them when they have been weakened or damaged by disease or injury.

A common objection to this is that it leads to an instrumental view of human beings, materialist and fragmented, and that medical science and hospitals never consider the human being as a whole, in its totality, but reduce it to components, and also leave out the existential dimension of being human. But as long as the medications and the operations actually work, as long as the coronary arteries can be cleared of plaque, or the brain drained of blood after a stroke, thereby perhaps prolonging the patient’s life by several decades, the objection seems as odd as it would have seemed to an auto repair shop if one were to point out that the focus on individual wires and fan belts, spark plugs and engine oil levels, diverted attention from the car as a whole. Car healing will never become a widespread phenomenon, we will never see incense burning and prayer in an auto repair shop or mechanics who attempt to fix a car by washing and polishing it. The fact is that the heart is a pump with four chambers, the action of which causes a red fluid to circulate through the body’s system of transmission lines, and that the neck is a tube through which bundles of nerves run from the brain into the body.

The first time I really understood this aspect of the body was when I read about a woman who had taken a fall while she was skiing, and had lain unconscious for a long time with her head underwater in a stream. When she was found, her body temperature was extremely low, and for all practical purposes she was dead. Her heart was restarted, but her condition remained critical, and as far as I understood, to reheat her body too quickly would have placed too great a strain on her system, so what the doctor did was to lead her blood out into the room and let it do a round in a tube there, before it was led into her again, slightly warmer, until her body temperature returned to normal. She survived, with no serious injuries.

This story shocked and fascinated me at the time, it seemed almost like a revelation, not of the divine, but of its opposite, the mechanical nature of the body, its automata-like properties, that the doctors, those engineers of the flesh, could repair as if it were a clock or a hydraulic crane. I had always known this, that hands can be stitched back on and myopia burnt off, intestines removed and stomachs sewn up, but the simplicity of these operations vanishes from view in the sterile and blinking order of the operating rooms, in the—to me—unattainable expertise and professionalism of the doctors, all the smocks and special equipment, which in this particular case was completely trumped by the provisional, simple and improvised nature of the doctor’s solution, it seemed like something I could have come up with myself, related to the way children play with water, hoses, channels. Any thought of the sacredness of human life, the grandeur and mystery of it, was stripped away in a second, and I saw the body for what it is, a construction of bones, strings, tubes, and liquids, that you can tinker around with if something inside it should break. Why, I would not have been surprised if the doctor had patched a burst blood vessel with a wad of chewing gum.

This story shocked and fascinated me at the time, it seemed almost like a revelation, not of the divine, but of its opposite, the mechanical nature of the body, its automata-like properties, that the doctors, those engineers of the flesh, could repair as if it were a clock or a hydraulic crane. I had always known this, that hands can be stitched back on and myopia burnt off, intestines removed and stomachs sewn up, but the simplicity of these operations vanishes from view in the sterile and blinking order of the operating rooms, in the—to me—unattainable expertise and professionalism of the doctors, all the smocks and special equipment, which in this particular case was completely trumped by the provisional, simple and improvised nature of the doctor’s solution, it seemed like something I could have come up with myself, related to the way children play with water, hoses, channels. Any thought of the sacredness of human life, the grandeur and mystery of it, was stripped away in a second, and I saw the body for what it is, a construction of bones, strings, tubes, and liquids, that you can tinker around with if something inside it should break. Why, I would not have been surprised if the doctor had patched a burst blood vessel with a wad of chewing gum.

To compare the body with clocks and automata is something people began to do in the seventeenth century, the mechanical century, the spirit of which was perhaps best captured by Descartes and Newton, and which is still present in our view of the world and ourselves, for while new knowledge may arise quickly, insight travels slowly. It takes generations before a discovery or a phenomenon out there gains enough weight to sink in and change what is in here, if it ever does.

That quantum physics and quantum mechanics found their expression as early as the 1920s made no difference to the teaching of physics and chemistry when I was at school sixty years later; no one told us that the discoveries made by Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli, Dirac, Sommerfeld, and all the other physicists of the interwar period had in fact revolutionized our knowledge of the material world. The same holds for genetic engineering, for even though we know that a revolution has taken place in this field, after the mapping of the genome, and that it is now possible to clone animals, probably even humans soon, that it is possible to extract genes from fish and insert them into plants, and that cultivating organs for transplantation, and not just on the backs of mice—in other words, mass-producing them, is no longer science fiction, we don’t care, we don’t take it in, we don’t allow it to change a single thing in our thoughts and conceptions of what it is to be human.

This may be because we are extremely adaptable, we are constantly turning the future into the present, the unknown into the known, this is how we have always existed in the world. It may also be because culture, which is to say language, soaked through as it is with conceptions and world views, is so sluggish that it either fails to perceive the new—that it is, so to speak, beyond the reach of novelty—or it sees the new as a variation of the old. Or it may simply be that being human is always the same, regardless, that the force of it, being cast into the world with all one’s senses and needs, is immutable. A beer is malt and hops and water, it tastes good and quenches thirst. A loaf of bread is grains and yeast, it tastes good and fills the stomach. The sun shines and gives warmth. The grass beneath my bare feet is soft and pleasant to the touch. A chopped-off human head is the most terrifying of all sights.

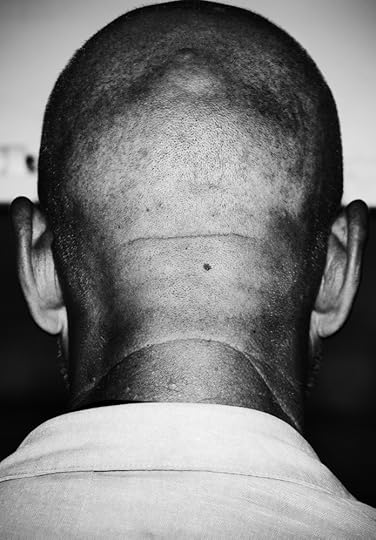

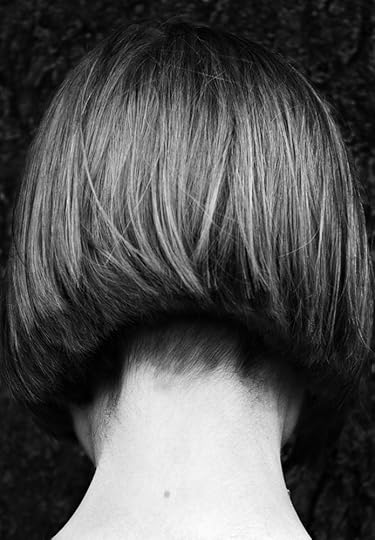

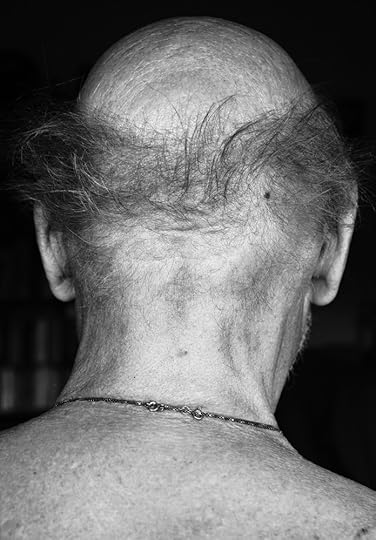

When I study the photographs in Thomas Wågström’s book, which are of necks, that is what I see. A neck cannot be modern. A neck is in time, belongs to time, but is not formed by it. If these photos could have been taken ten thousand years ago, they would have looked the same. My guess is that even photos of Neanderthal necks would not differ significantly from these. In other words, the neck is untouched by culture, it is, in a certain sense, pure nature. Something that grows in a certain place, the way tree trunks grow, or mussels, fungi, moss.

But is this really true? And if so, what does it mean? In that case, does it not also hold true for all the other parts of the body, such as the face, the knees, the heart, the fingers?

In a certain sense, of course, it does. There is such a thing as a human being as it is in itself, a pure object in the world; this is the naked body, the body as biological matter. But, and this is a major objection, this body is inaccessible to us. We can’t see it. Nor can we be it. For the biological body, the human being as pure nature, is swathed in thoughts, conceptions, ideas of such diversity and opulence that not one square inch of the body or the world is untouched by them.

In a certain sense, of course, it does. There is such a thing as a human being as it is in itself, a pure object in the world; this is the naked body, the body as biological matter. But, and this is a major objection, this body is inaccessible to us. We can’t see it. Nor can we be it. For the biological body, the human being as pure nature, is swathed in thoughts, conceptions, ideas of such diversity and opulence that not one square inch of the body or the world is untouched by them.

A face? We see what the face communicates, what it “tells” us. We enhance communication, we apply lipstick, mascara, we wear glasses, grow a beard, whiskers, or we don’t, but even a naked face tells us something, every look is a form of address, and a downturned gaze is not nothing, it is a non-address, a turning away. In the world of images we inhabit today, there is hardly a single part of the body that has not been exploited, sexually, commercially, or intellectually. Breasts, bottoms, thighs, calves, feet. Backs, biceps, six-pack abs. Cunts and cocks. Toes and fingers with nails lacquered red. Pierced tongues. Inner organs are bought and sold in the Third World; in the First World, the transactions take place between the living and the dead, in so-called organ transplants. In this sense, the neck is perhaps the only body part left that is not for sale, that is not on view in magazines and periodicals, that doesn’t serve as the owner’s marketing site or display window, that doesn’t change owners after death, and which, in contrast to its front side, the face, hardly communicates anything, neither contemporaneity, nor culture, nor community, and thus appears “mute.” And this is why, I think, that in looking at the neck, as these photos lead us to do, we get the feeling that we are being offered a glimpse of the body as it is in itself, non-individual, non-relational, biological, whole, and authentic. Something growing in a certain place in the world.

But the fact that the neck is unexploited visually and commercially of course does not mean that it stands outside of the culture, to the contrary, the neck, too, is loaded with meaning. It means only that it is marginal, somewhat forgotten, most often associated with not seeing, and with not being seen, that is, with negation, in contrast to the heart, for instance, which is also blind and mute, but in touch with a whole other wealth of signification. The heart signifies love, it means warmth, kindness, consideration. She has a big heart, home is where the heart is, our heartfelt sympathy, his heart is broken. The heart is life, light, love, compassion. The only figurative sense assigned to the neck that I can think of is found in the expression stiff-necked, that is, stubborn, obdurate, willful, intractable, impossible. To be stiff-necked is not to give way, not to yield a single inch, to always know best, always keep one’s cards close to one’s chest. The meaning can be extended to uprightness, which is the positive variant of being stiff-necked, that is, not relinquishing one’s pride and self-respect, holding one’s ground. Thus, the neck, in a certain sense, is linked to an existence outside of the community. The opposite, in the symbolic language of the neck, is to be stooped, that is, cowed, at the mercy of others, but in a more passive and less voluntary sense than when one bows deeply or kneels, out of respect for the other or in awe of the sacred.

It may seem as if the neck, in the symbolic language of body parts, has assumed the place between humility and pride, self-surrender and self-righteousness, but in a most discrete, gray eminence–like way, present only indirectly, as opposed to the more imposing organs and joints, like the brain, the symbol of intelligence, associated with a certain coldness and distance, but also with clarity and objectivity, not drowning in a heaving sea of vague emotions and sentimentality as one who thinks with the heart is.

In the metaphysics of the body, the neck forms the link between the reason of the mind and the light of the spirit, and the irrationality of the body and the darkness of desire. In other words, the neck is the place between and the place outside. To be stiff-necked, as opposed to cowed, does not refer only to exposing your neck or not, appearing defenseless or not, for when you bow your head you also conceal your gaze from the other. To look into someone’s eyes is to signal that you are equals, while to look down is to subordinate yourself to the gaze of the other, to no longer be on the same footing. It can also mean keeping something hidden, one’s true self, or something in it that one does not wish to be seen. The downturned gaze may contain hatred, or shame, or, as is often the case, both at once.

The primordial image of the bowed head and the downturned gaze is found in the Bible, in the story of Cain and Abel, where it is written about Cain that “his face fell.” Jahveh asks why Cain’s face has fallen, and continues: “If you do well, will not your countenance be lifted up? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door, and its desire is for you, but you must master it.” This touches the very core of what it is to be human, as I see it, namely, that to be in yourself is inhuman, since that which is human is always something that becomes in relation to something else, yes, the human is this otherness, that we become ourselves in and that we exist in. To bow down is to bow down before something, to be stiff-necked is to be stiff-necked in the face of something, to worship is to worship something, and to look down is also to look away from something. This relativity, which is as complex as it is abstract and intangible, since it occurs in the spaces between, and has no object, no place of its own, never fixed, always in motion, turns the concept of biological man into a fiction, an image among images, nothing in itself, except in death, when for the first time the body no longer grasps at something, no longer seeks anything, and only then is it something in itself, that is to say, no longer human.

And perhaps this is the real and simple insight afforded by the sacrifice, that we are creatures of flesh, filled with blood, and that we are going to die. What sacrifice does is to penetrate every layer, every veil of culture, and in a gesture devoid of meaning in any other sense than this, it reveals to us the otherwise always inaccessible truth about our existence, of what we are in the world.

Just a few days ago—sixteen, to be precise—I found myself in the middle of an existential situation of quite another order. It was in a hospital in Helsingborg, up on the second floor, from the window there was a view of a parking building, and behind that a residential area, whose myriad lamps drew an arc of light under the otherwise black sky. Not that I was thinking of this at the time. We were expecting our fourth child; the mother-to-be was lying in bed with an elastic strap around her huge belly, I was in a chair beneath the window, fiddling with my mobile phone. Once in a while a midwife or a nurse would enter the room to see if anything was happening. The room was clinical and packed with technical equipment, I could see an oxygen tank, a defibrillator, and right next to me stood a monitor on which you could read the child’s heartbeat and the mother’s contractions as graphs and digits. The room was strongly lit, the metal beds adjustable, in front of the sink there was one dispenser for disinfectant and another one for soap. When, shortly after, the contractions began to quicken and the birth got underway, all of this vanished. The mother was on her knees, with her torso hanging over the end of the bed. Every time she had a contraction, she grabbed the mask with laughing gas and inhaled deeply. From time to time she shouted into the mask. Waves seemed to ripple through her, and she fell into their rhythm as if into a trance, and the rhythm seemed to transport her to another place, of pain, body, darkness. Her shouts were hollow and seemingly endless, with no beginning nor end. They became darker, more animal, and contained a pain and a despair so great that whatever I did, whether it was wrapping my arms around her and pressing my cheek to hers, or rubbing her back, it was no more than feeble, futile ripples on the surface of the deep that engulfed her. She was in the middle of something, in a place I could never reach, but only observe from the outside, and yet it changed everything for me, too, it was like a tunnel, the sides of which dissolved the material world in dimness: emotions forced their way through and took over, my gaze was filtered through them. She turned over on her side and no longer breathed regularly, no longer removed the mask when the breakers of pain withdrew, but lay there screaming at the top of her lungs until she had no more air left in her, then she drew a new breath and screamed again, a scream that, though it was partly swallowed up by the mask, was still piercing, and unlike anything I had heard before. Shortly after, the child tumbled out onto the bed. It was purplish, the thick umbilical cord nearly blue. It was a girl, the head was compressed and glistening, the face wrinkled, the eyes closed. She lay quite motionless. I thought, she’s dead. Three midwives came running, they rubbed the slippery little body, and she emitted her first scream. It was a feeble scream, more than anything it sounded like the bleating of a lamb.

Just a few days ago—sixteen, to be precise—I found myself in the middle of an existential situation of quite another order. It was in a hospital in Helsingborg, up on the second floor, from the window there was a view of a parking building, and behind that a residential area, whose myriad lamps drew an arc of light under the otherwise black sky. Not that I was thinking of this at the time. We were expecting our fourth child; the mother-to-be was lying in bed with an elastic strap around her huge belly, I was in a chair beneath the window, fiddling with my mobile phone. Once in a while a midwife or a nurse would enter the room to see if anything was happening. The room was clinical and packed with technical equipment, I could see an oxygen tank, a defibrillator, and right next to me stood a monitor on which you could read the child’s heartbeat and the mother’s contractions as graphs and digits. The room was strongly lit, the metal beds adjustable, in front of the sink there was one dispenser for disinfectant and another one for soap. When, shortly after, the contractions began to quicken and the birth got underway, all of this vanished. The mother was on her knees, with her torso hanging over the end of the bed. Every time she had a contraction, she grabbed the mask with laughing gas and inhaled deeply. From time to time she shouted into the mask. Waves seemed to ripple through her, and she fell into their rhythm as if into a trance, and the rhythm seemed to transport her to another place, of pain, body, darkness. Her shouts were hollow and seemingly endless, with no beginning nor end. They became darker, more animal, and contained a pain and a despair so great that whatever I did, whether it was wrapping my arms around her and pressing my cheek to hers, or rubbing her back, it was no more than feeble, futile ripples on the surface of the deep that engulfed her. She was in the middle of something, in a place I could never reach, but only observe from the outside, and yet it changed everything for me, too, it was like a tunnel, the sides of which dissolved the material world in dimness: emotions forced their way through and took over, my gaze was filtered through them. She turned over on her side and no longer breathed regularly, no longer removed the mask when the breakers of pain withdrew, but lay there screaming at the top of her lungs until she had no more air left in her, then she drew a new breath and screamed again, a scream that, though it was partly swallowed up by the mask, was still piercing, and unlike anything I had heard before. Shortly after, the child tumbled out onto the bed. It was purplish, the thick umbilical cord nearly blue. It was a girl, the head was compressed and glistening, the face wrinkled, the eyes closed. She lay quite motionless. I thought, she’s dead. Three midwives came running, they rubbed the slippery little body, and she emitted her first scream. It was a feeble scream, more than anything it sounded like the bleating of a lamb.

Up until that moment, no one and nothing had been able to reach her, she had lain surrounded by water in the middle of another body, and for a few seconds she remained untouched in the world, as she lay there, as if dead, shut up in herself, without breathing and with her eyes closed, but then hands reached out to touch her, and then she drew her first breath, not without pain, I assume, and the world flowed into her. I have never seen it so clearly before, how a new human being is literally lifted into the community by other people, that this is what happens. A newborn baby has no muscles in its neck, and its vulnerability and helplessness are absolute, it can’t move itself, nor even raise its head, but has to be supported by the hands of others, lifted up to the faces of others, which are the first thing she sees as she opens her eyes. And then she enters the circle of faces, in which she will live out the rest of her life.

* * *

For quite a few years, I thought that being a child was like being a prisoner, at the mercy of adults’ favors and whims, and that to be a parent was to be a prison warder. Now I think maybe it is the other way around. That the child is the one who is free, the adults are the captives. Occasionally this thought extends as far as to consider that childhood is the true meaning of life, the apex of our existence, while all the rest of life is one slow journey away from it, where the main task is to be at the disposal of those who are now at the center of existence, that is, the children. Perhaps this is why I have always liked Heraclitus’s image of the god as a child playing somewhat carelessly with pieces on a checker board; I may have sensed somehow, as with so many other fragments of this pre-Socratic philosopher, that it was true.

This, you are probably thinking, says more about me than about childhood. For if childhood is supposed to be the zenith of life, what about sex? What about the desires of the flesh? What of ambition, zeal, heroics, career? What of insight, wisdom, experience, the accumulated weight of life? How about progress, conquest, riches, and splendor? Politics, science, the project of the Enlightenment? To put children and childhood before all this testifies not only to a considerable regression, but to an enormous resignation. Knowledge increases pain, the Bible says, and surely only an immature person could opt for ignorance in order to evade pain. Being able to handle complexity is part of being an adult, and as for sex, which is the central obsession of our culture, and which, when all is said and done, may well be the most powerful force in our lives, to ignore it bears witness not only to puritanism and notions of purity, and not only to the fear of the body (which in my case must be understood as a fear of women) inherent in these two concepts, but to a longing for simplification which at its core is barren, unproductive, lifeless, even dead: the child does not create anything, it simply is.

The biggest difference between being a child and being an adult has to do with the lack of boundaries, that feeling of vastness that one has as a child, where time and the world appear infinite, and this infinity is taken for granted, since neither time nor the world is something you think about, but something you move within, and which keeps opening up, room after room, farther and farther in. The land of childhood, the expression goes, or the valley of childhood: Portraying time as topography is a way of expressing that the divide between child and adult is too great or too comprehensive for it to be due simply to time. The world of childhood is radically different from that of the adult. To me, a summer day now is divided up into different tasks, and has no weight of its own. I can make breakfast, I can pack swimming gear, drive to the beach, lie on a towel and keep an eye on the kids, feed them oranges or sodas, hand them towels when they emerge from the water, maybe check my mobile from time to time. Drive home, cook dinner, eat, since the weather is nice we eat outside, in the shade of a tree. Wash the dishes, do a load of laundry. Maybe read a little as the day fades, hang up the washing, talk on the phone, put the kids to bed, smoke a last cigarette outside in the light of the summer evening, go to bed. Little of this has any intrinsic meaning, and all this time I have been observing it without entering into it, without losing myself in it. The boundary between myself and my surroundings has been sharp, and the day has been divided up into a sort of coordinate system, which in a similar way has kept me on the outside of it. I have been free, since I could just as easily have done something else entirely, stayed at home and worked in the garden, taken the kids for a drive into town, or for that matter just kept on driving south, into Denmark, through Germany and down to Munich, for example. If the children had protested, I could have employed some of the means at my disposal as an adult, ranging from outright bribes to force and gentle violence. Children are almost always subject to the appraisal and actions of adults, and in that sense they are unfree. And when I spend my days with them in this way, I see them doing what they are doing based on my own approach to the world, where the days whirl away, as if down a drain, one after the other, without any one of the day’s events ever overwhelming me. This is time as quantity, this is life as matter. That it may be different for the children is hard to grasp, since we live side by side and share almost everything that happens. And yet I suspect that they do experience these days differently, for I can still remember what it was like to be a child, when the sun rose above the spruce trees to the east and filled the house with light, and I walked barefoot across the rust-colored wall-to-wall carpet, then over the golden parquet floor and finally the fractionally colder linoleum, on my way from the bedroom to the kitchen, where I would eat breakfast. The sun was like a person, or not like a person, more like a figure or creature with which I had a personal relationship, a kind of intimacy. There it was again, hazy, yellow, glowing. This intimacy, which did not just apply to the sun, but to all things and phenomena, is impossible to explain, I now find, for it appears to be a personification of the world, imbuing it with spirit, but it wasn’t, it was something else, a sort of interiorization, perhaps, as if I approached objects and phenomena in the world in the same way that I approached familiar faces, with the same trust, without ever having thought of the sun or all the rest of it as persons, as being alive. It was rather that everything had a face, every tree, every hillock, every bicycle, and therefore was something I felt connected to, for I saw the tree, the hill, the bicycle, and I recognized them. This way of seeing is gone. The sun is the sun, a tree is a tree, a hill is a hill, a bike is a bike. I no longer regard the world the way I look at faces, it is as if the faces have turned away from me.

The biggest difference between being a child and being an adult has to do with the lack of boundaries, that feeling of vastness that one has as a child, where time and the world appear infinite, and this infinity is taken for granted, since neither time nor the world is something you think about, but something you move within, and which keeps opening up, room after room, farther and farther in. The land of childhood, the expression goes, or the valley of childhood: Portraying time as topography is a way of expressing that the divide between child and adult is too great or too comprehensive for it to be due simply to time. The world of childhood is radically different from that of the adult. To me, a summer day now is divided up into different tasks, and has no weight of its own. I can make breakfast, I can pack swimming gear, drive to the beach, lie on a towel and keep an eye on the kids, feed them oranges or sodas, hand them towels when they emerge from the water, maybe check my mobile from time to time. Drive home, cook dinner, eat, since the weather is nice we eat outside, in the shade of a tree. Wash the dishes, do a load of laundry. Maybe read a little as the day fades, hang up the washing, talk on the phone, put the kids to bed, smoke a last cigarette outside in the light of the summer evening, go to bed. Little of this has any intrinsic meaning, and all this time I have been observing it without entering into it, without losing myself in it. The boundary between myself and my surroundings has been sharp, and the day has been divided up into a sort of coordinate system, which in a similar way has kept me on the outside of it. I have been free, since I could just as easily have done something else entirely, stayed at home and worked in the garden, taken the kids for a drive into town, or for that matter just kept on driving south, into Denmark, through Germany and down to Munich, for example. If the children had protested, I could have employed some of the means at my disposal as an adult, ranging from outright bribes to force and gentle violence. Children are almost always subject to the appraisal and actions of adults, and in that sense they are unfree. And when I spend my days with them in this way, I see them doing what they are doing based on my own approach to the world, where the days whirl away, as if down a drain, one after the other, without any one of the day’s events ever overwhelming me. This is time as quantity, this is life as matter. That it may be different for the children is hard to grasp, since we live side by side and share almost everything that happens. And yet I suspect that they do experience these days differently, for I can still remember what it was like to be a child, when the sun rose above the spruce trees to the east and filled the house with light, and I walked barefoot across the rust-colored wall-to-wall carpet, then over the golden parquet floor and finally the fractionally colder linoleum, on my way from the bedroom to the kitchen, where I would eat breakfast. The sun was like a person, or not like a person, more like a figure or creature with which I had a personal relationship, a kind of intimacy. There it was again, hazy, yellow, glowing. This intimacy, which did not just apply to the sun, but to all things and phenomena, is impossible to explain, I now find, for it appears to be a personification of the world, imbuing it with spirit, but it wasn’t, it was something else, a sort of interiorization, perhaps, as if I approached objects and phenomena in the world in the same way that I approached familiar faces, with the same trust, without ever having thought of the sun or all the rest of it as persons, as being alive. It was rather that everything had a face, every tree, every hillock, every bicycle, and therefore was something I felt connected to, for I saw the tree, the hill, the bicycle, and I recognized them. This way of seeing is gone. The sun is the sun, a tree is a tree, a hill is a hill, a bike is a bike. I no longer regard the world the way I look at faces, it is as if the faces have turned away from me.

Back then, on those summer mornings when I sat eating my breakfast and gazing at the landscape outside, the dry asphalt road with sand dust along the edge of the sidewalk, the houses, the spruce trees, and beyond the tree tops, the sound, and on the other side of the sound, the forest and the big white tanks, containing I still don’t know what—gas, maybe?—all of this was connected to me, by its appearing to me as something familiar. This familiarity or intimacy may seem like an addition, for now the world is just the world, but back then it was always something more, but it wasn’t an addition, it was just the reverse, it was that the object or the phenomenon was seen as something in itself, something in its own right, with an identity of its own, this is what created the intimacy that gave everything a face.

It’s easy to think that now I see the world as it really is, as faceless, blind and mute matter. Just as these photographs of necks allow me to see the human being as it really is, flesh and blood, cells and strings, biology. In everything I write, there is a longing for out there, to that which is real, outside of the social realm, while at the same time I am aware that what is out there, beyond the light of the faces, and which we occasionally catch a glimpse of, through art, turns everything to nothing. That the experience of the sublime is the experience of nothing. That God is nothing, which we exists in spite of. And this is why the real is such a dangerous category. In ourselves, as bodies of flesh and blood, things growing somewhere in the world, we are nothing, and I think this is why I am so fearful of the cultivation of organs, the manipulation of genes, of the human machine on an operating table, since even though it saves and prolongs life, it also reduces it, brings it closer to nothing, a wire, a string, a tube, a gutter.

If that is true, what do we need truth for?

Back then, when the world was made up of faces, I didn’t know what went on, or why what happened happened, it just did. Why, for instance, was I so obsessed, at the age of seven or eight, with looking at myself in the mirror, not just frontally, but from the sides and even from the back? I stood there on the bathroom floor with a small, round mirror in one hand, and directed it toward the large bathroom mirror in front of me at ever changing angles, so that I could see myself in varying forms of profile, and finally, from the back and from above, so that the back of my head and the nape of my neck became visible. What I saw made me very uncomfortable. So this is what I also looked like? I had gotten used to and accepted my face, but not this. But this is what other people saw, this is how I appeared to them, perhaps that is why I explored it. I felt a similar unease the first time I heard a recording of my own voice, and the first time I watched my own movements on a TV screen. It was alienating, I couldn’t possibly identify it with myself, the way I was, it made it seem as if I was suddenly also someone else. That it was this other person that everyone else saw and heard, bothered me. It still bothers me at times, the unease caused by non-identity.

Now that I have children of my own, I look at the self-mirroring and the self-listening not as a result of narcissism or self-absorption (though it was that, too), but as part of being socialized, becoming an independent individual. To be socialized is to learn to see yourself as you appear to others. To bring up a child is really nothing other than representing or personifying this, the gaze and the voices of others, for at the outset the child possesses only a sort of undifferentiated self, permeated by feelings and needs, which can be, as it were, lit or extinguished, but not otherwise controlled. Since this is all, it is also nothing, that is to say, unknown. Something is lit, something is extinguished. All the boundaries one gradually imposes as a parent, all the prohibitions and commands, do not only have to do with teaching the child how to behave, are not just about making it function without friction in daily life, though that is perhaps often the motivation, but it is also always a gaze, it is also always a place from which the child can see itself from the outside, from a place other than the self, which only then can emerge as its own, whole self. It becomes an adult. One process is completed, and another sets in: slowly the world turns its face away.

Now that I have children of my own, I look at the self-mirroring and the self-listening not as a result of narcissism or self-absorption (though it was that, too), but as part of being socialized, becoming an independent individual. To be socialized is to learn to see yourself as you appear to others. To bring up a child is really nothing other than representing or personifying this, the gaze and the voices of others, for at the outset the child possesses only a sort of undifferentiated self, permeated by feelings and needs, which can be, as it were, lit or extinguished, but not otherwise controlled. Since this is all, it is also nothing, that is to say, unknown. Something is lit, something is extinguished. All the boundaries one gradually imposes as a parent, all the prohibitions and commands, do not only have to do with teaching the child how to behave, are not just about making it function without friction in daily life, though that is perhaps often the motivation, but it is also always a gaze, it is also always a place from which the child can see itself from the outside, from a place other than the self, which only then can emerge as its own, whole self. It becomes an adult. One process is completed, and another sets in: slowly the world turns its face away.

What applies to the identity of the individual also applies to that of the culture, if not in quite the same way, then in accordance with the same principle; it is continuously setting its own boundaries, and always seeks to see itself from the outside. If this is necessary, or why it is necessary, I don’t know; the answer to that is the same as the answer to the question of why we have art, or why art is necessary. We live in the social realm, which is sameness, the light of the faces, but we exist in the non-identical, in what is unknown to us, it is the other side of the face, that which turns away mutely, beyond the reach of language, just as the blood trickling through the tiny capillaries of the brain is beyond the reach of the thoughts thinking them, a few millimeters away, in that which upon closer inspection turns out to be nothing more than a chemical and electrical reaction in the spongelike object that the neck holds aloft.

Translated from the Norwegian by Ingvild Burkey.

All photographs © Thomas Wågström.

Karl Ove Knausgaard was born in Norway in 1968. His debut novel, Out of This World, won the Norwegian Critics Prize in 2004 and his A Time for Everything was a finalist for the Nordic Council Prize. For My Struggle: Book One, Knausgaard received the Brage Award in 2009, the 2010 Book of the Year Prize in Morgenbladet, and the P2 Listeners’ Prize. My Struggle: Book One was a New Yorker Book of the Year and Book Two was listed among the Wall Street Journal's 2013 Books of the Year; Book Three has just been published in the US. My Struggle will be published in at least twenty-two languages. Knausgaard lives in Sweden with his wife and four children.

A version of this essay originally appeared in Neckar (Necks) , a book of Thomas Wågström’s photographs published in Sweden by Max Ström. © 2014; reprinted with permission.

Supine Access to Your Favorite Tome, and Other News

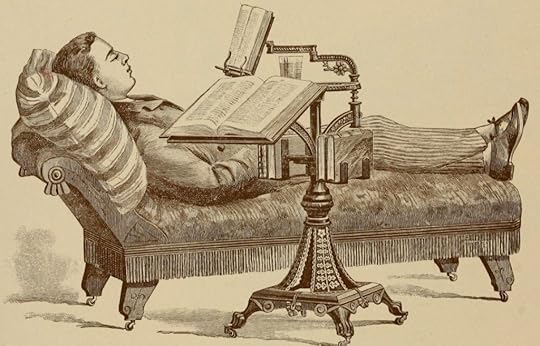

An illustration from an advertisement for the Holloway Reading Stand and Dictionary Holder, c. 1892; image via Retronaut.

Around 1892, the world of books greeted perhaps the most salient advance since the invention of the printing press: the Holloway Reading Stand and Dictionary Holder. “For invalids and those accustomed to read themselves asleep it is invaluable … The tired man or woman may read while resting.”

Working for J. D. Salinger’s agent: “One of Ms. Rakoff’s tasks was to respond to the steady stream of fan mail for the legendarily reclusive author … The letters, many of them handwritten, were personal and passionate. There were old men who had served with the author in the war and young people discovering the hypocrisy of the real world for the first time. Ms. Rakoff went off script and began to write back, giving the fans her own advice and opinions.”

What explains the spate of novels about famous novelists’ wives? “Vera Nabokov, as far as I know, has not yet been transformed into the heroine of a novel. But it's only a matter of time. The demand for fiction cast in the template of ‘the creative person’s wife’ shows little sign of abating.”

Remembering Bernard Natan, “a Romanian Jew who immigrated to Paris in 1905 and went on to become a titan of French film, a man whose brand name, for a time, rivaled that of Gaumont and Pathé, founding fathers of le cinéma français. At once media visionary and rapacious entrepreneur, he burned bright over the City of Lights until an arrest for fraud sent him crashing to earth.”

“An emergency gives reading a practical urgency, but practical urgency and literature have little business mixing. This is exactly why reading, at its best, is good for you: there’s almost never an immediate, practical reason to do it. It cuts against the grain of the everyday—of the jobs we have to work, the bills we have to pay, the conversations and fashions we’ve been convinced we need to keep up with, the stock language and thought that float in our cultural ether, clogging our vision.”

May 27, 2014

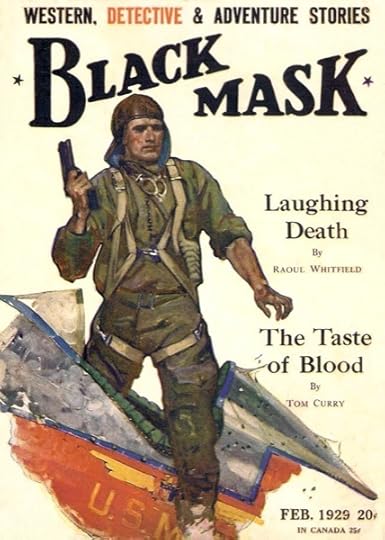

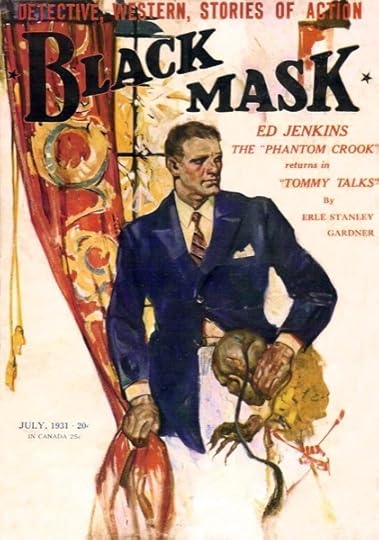

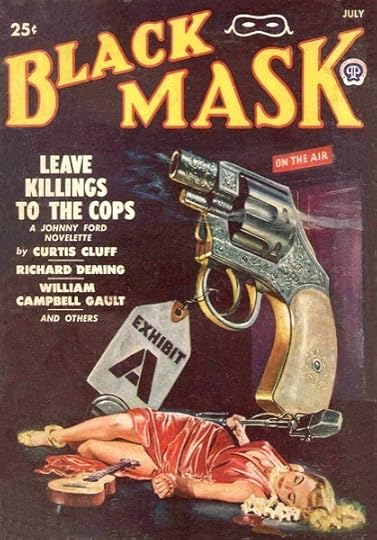

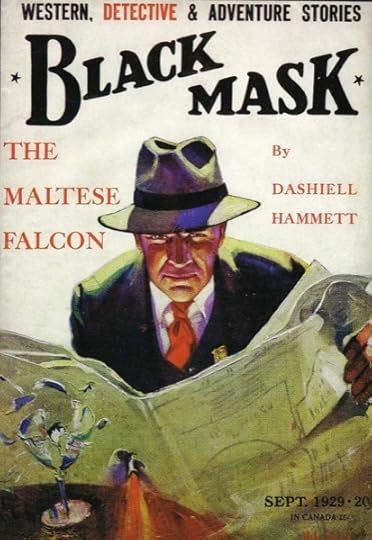

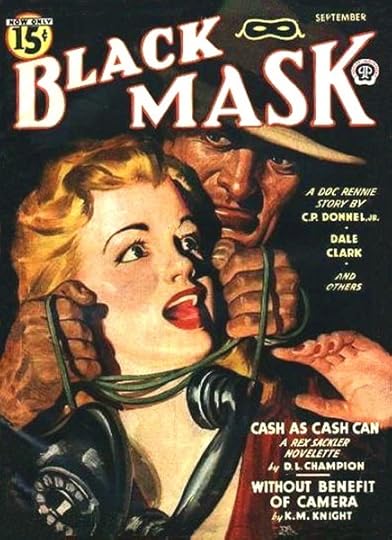

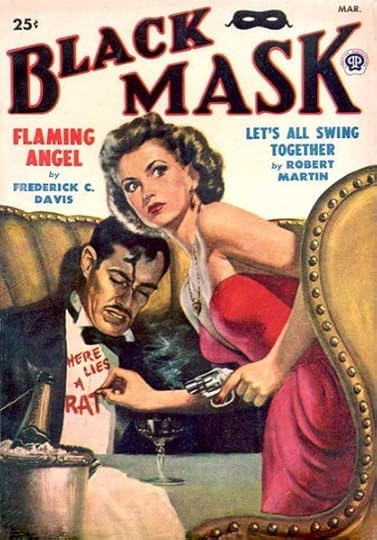

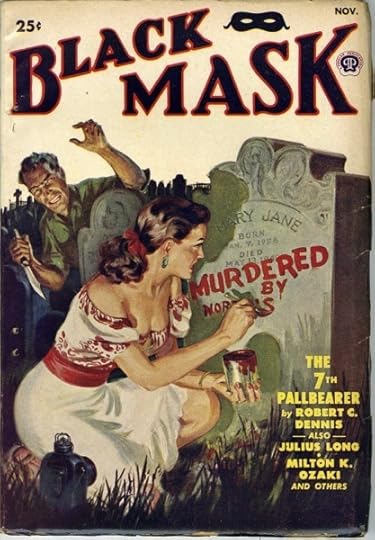

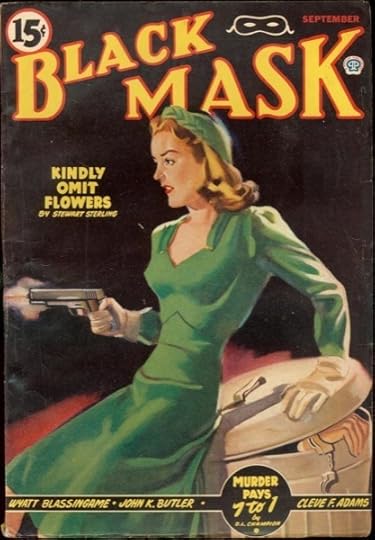

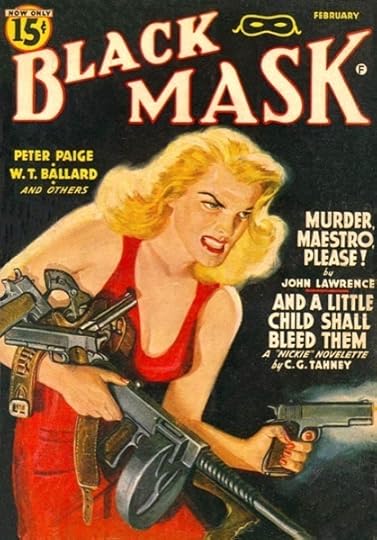

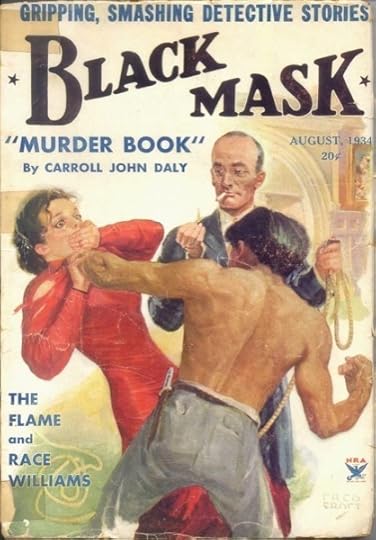

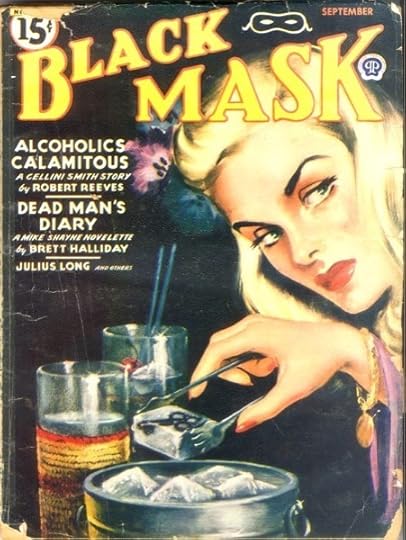

Some Pulp

Dashiell Hammett, born today in 1894, found a home for a lot of his fiction in Black Mask, one of America’s great bygone pulp magazines. Raymond Chandler, Carroll John Daly, and other masters of detective fiction all placed their work in Black Mask, which first published Hammett in 1922, and which serialized The Maltese Falcon in 1929. The magazine had high-minded origins—H. L. Mencken cofounded it in 1920 as a lucrative companion to his more literary (read: less profitable) journal, The Smart Set, which also published Hammett, though later he decided to slum it and began to appear solely in Black Mask. Mencken and his partner sold the pulpier magazine only eight issues into its run; I guess they thought they’d made enough money on it by then. Tant pis—The Smart Set (“A Magazine of Cleverness”) met its demise in 1930, when Black Mask had a circulation of 130,000.

Alack, the forties saw a decline in fortune, as a fan’s history of Black Mask explains:

By 1940 circulation had dropped ... and the owners decided to sell Black Mask to their competition, Dime Detective. A new editor tried to make the magazine tough again and brought in new writers, but the problem was no longer the magazine. The technology of entertainment was changing. Readers had taken up comic books and mass-market paperbacks during the Depression, and by 1940 radio was also taking away audience. These media were, variously, either cheaper or more durable or resalable or more immediate. Its days numbered, Black Mask staggered on, using lurid covers of sex and violence, featuring espionage stories during World War II and finally cutting back to fortnightly publication. The magazine’s size was reduced, the price raised—nothing helped. The last issue appeared in July 1951. After thirty-one years of publication, Black Mask folded: it had printed over 2,500 stories by some 640 authors and been the dominant magazine in hard-boiled fiction.

It was Black Mask, particularly the aforementioned grotesqueries of its later years, that inspired Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, and the covers here offer images out of a Tarantino wet-dream: unabashedly titillating, chock full of lantern-jawed private dicks and glinting gunmetal and doe-eyed doll-faced dames who like to leave messages in lipstick (or blood). Serialized novels were called novelettes, not novellas (“The Flying Hearse: A Cellini Smith Novelette”); headlines ran to all shades of yellow and purple. “Leaving Killings to the Cops.” “Let’s All Swing Together.” “The ‘Phantom Crook’ Returns in ‘Tommy Talks.’” “And a Little Child Shall Bleed Them.” “Alcoholics Calamitous.”

Of course, Hammett’s frequent appearances in these pages might imply that he was just part of the hard-boiled schlock-peddling machine, and I suppose he was. But all you do have to do is read a few lines of dialogue from The Maltese Falcon to see why he outlasted his contemporaries—there was no tough-as-nails before Sam Spade was tough-as-nails.

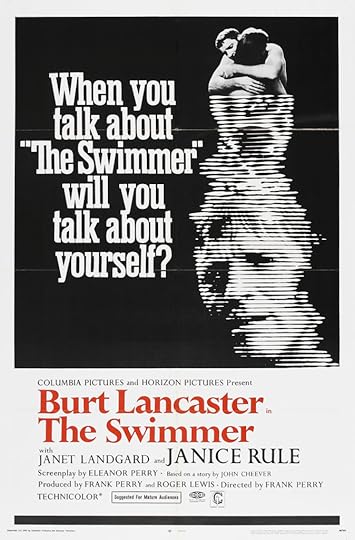

“The Swimmer” and The Swimmer

It’s John Cheever’s birthday, and courtesy of 92Y, you can listen to a recording of the author reading his most famous story, “The Swimmer,” in December 1977. It’s easy to shrug off such a canonical piece of fiction, especially when its hero is named Neddy. But if you, like me, haven’t glanced at it since it appeared on one syllabus or another, “The Swimmer” is worth rereading; though its more surreal elements feel contrived to me, the prose still glitters and the dark humor survives:

It would storm. The stand of cumulus cloud—that city—had risen and darkened, and while he sat there he heard the percussiveness of thunder again. The de Haviland trainer was still circling overhead and it seemed to Ned that he could almost hear the pilot laugh with pleasure in the afternoon; but when there was another peal of thunder he took off for home. A train whistle blew and he wondered what time it had gotten to be. Four? Five? He thought of the provincial station at that hour, where a waiter, his tuxedo concealed by a raincoat, a dwarf with some flowers wrapped in newspaper, and a woman who had been crying would be waiting for the local.

I hadn’t known, though Google suggests it’s common knowledge, that “The Swimmer” was adapted into a feature-length film, released in 1968, starring Burt Lancaster as Neddy. According to a thorough assessment at Turner Classic Movies, The Swimmer succeeds in adapting the unadaptable:

It succeeds brilliantly as a fascinating, enigmatic drama that ponders middle-age disillusionment and failure. It’s one of those lucky accidents that occurred in the sixties when Hollywood was still open to experimentation because most studio executives were completely insecure in predicting commercial hits. After all, Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate (both 1967) had blindsided the industry with their unexpected box-office grosses. So maybe audiences were ready for more challenging films like The Swimmer? Unfortunately, the film was a box-office flop, but part of its commercial failure was due to poor marketing by Columbia.

Poor marketing indeed. All of Columbia’s efforts seem to have been built around an ominous, pseudointellectual slogan: “When you talk about The Swimmer, will you talk about … yourself?” Picture the average suburban moviegoer emerging from the cinema, running his mouth in enchantment—“Holy toledo, whatta crazy flick, glad I’m not that guy”—only to realize the film was … about him! And his upper-middle-class malaise!

The trailer is especially heavy-handed in this regard, though it does give the movie a perverse appeal, by virtue of how poorly it’s aged:

In spite of all that, the film collected a certain reluctant critical regard; in the Times, Vincent Canby wrote that it “has the shape of an open-ended hallucination. It is a grim, disturbing and sometimes funny view of a very small, very special segment of upper-middle-class American life.” And Cheever himself gave his imprimatur, in a way—one of the film’s party scenes features a cameo from the author, seen here inexplicably dubbed in Spanish.

Then again, Cheever doesn’t have many kind words for Hollywood—the industry or the place—in his interview for the Art of Fiction series:

CHEEVER

Writers of my generation and those who were raised with films have become sophisticated about these vastly different mediums and know what is best for the camera and best for the writer. One learns to skip the crowd scene, the portentous door, the banal irony of zooming into the beauty’s crow’s-feet. The difference in these crafts is, I think, clearly understood, and as a result no good film comes from an adaptation of a good novel. I would love to write an original screenplay if I found a sympathetic director. Years ago René Clair was going to film some of my stories, but as soon as the front office heard about this, they took away all the money.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of working in Hollywood?

CHEEVER

Southern California always smells very much like a summer night … which to me means the end of sailing, the end of games, but it isn’t that at all. It simply doesn’t correspond to my experience. I’m very much concerned with trees … with the nativity of trees, and when you find yourself in a place where all the trees are transplanted and have no history, I find it disconcerting.

I went to Hollywood to make money. It’s very simple. The people are friendly and the food is good, but I’ve never been happy there, perhaps because I only went there to pick up a check. I do have the deepest respect for a dozen or so directors whose affairs are centered there and who, in spite of the overwhelming problems of financing films, continue to turn out brilliant and original films. But my principal feeling about Hollywood is suicide. If I could get out of bed and into the shower, I was all right. Since I never paid the bills, I’d reach for the phone and order the most elaborate breakfast I could think of, and then I’d try to make it to the shower before I hanged myself. This is no reflection on Hollywood, but it’s just that I seemed to have a suicide complex there. I don’t like the freeways, for one thing. Also, the pools are too hot … eighty-five degrees, and when I was last there, in late January, in the stores they were selling yarmulkes for dogs—my God! I went to a dinner and across the room a woman lost her balance and fell down. Her husband shouted over to her, “When I told you to bring your crutches, you wouldn’t listen to me.” That line couldn’t be better!

Bringer of Jollity

“The sense of unhappiness is so much easier to convey than that of happiness. In misery we seem aware of our own existence, even though it may be in the form of a monstrous egotism: this pain of mine is individual, this nerve that winces belongs to me and to no other. But happiness annihilates us: we lose our identity.” —Graham Greene, The End of the Affair

A friend described to me yesterday what he considers the Three Degrees of Being Stood Up. As he explained, these proceed as follows:

First Degree: Standing someone up entirely, with no warning, and no subsequent apology.

Second Degree: Canceling on someone at the last minute, possibly after he or she has set out for the appointment in question.

Third Degree: Breaking a date.

He agreed that we have all been guilty of the third. I know I have, too often, and, indeed, was somewhat surprised to hear it grouped with the other two offenses. And yet, he was right: such things inconvenience others and maybe even hurt them. Besides practical questions of schedules and reservations, there are matters of disappointment and broken trust. After a certain point, you cease to depend upon people who make a habit of breaking dates. Maybe that’s what we want.

It was funny that this should come up just when it did, because only a few days before, another friend had observed, “people should have the self-esteem to know that their absence matters to other people.”

Both these pronouncements got me thinking about those occasions when one feels one really cannot muster the energy to be good company, to subject oneself to the possibility of some obscure rejection or bruising. Is it egotism, or self-abnegation? Is there, ultimately, a difference? (I am obviously not referring to cases of severe depression, which are another order of magnitude altogether.)

Neurotic writers can be a great comfort in moments of wallowing, but what about those times when you need to jolly yourself out of it? When you cannot give in to what the decorator and entertaining doyenne Dorothy Draper terms the “Will to be Dreary”? It is in these cases that a certain kind of hearty, unreflective, jolly type is called for. Draper herself, for instance: she seems to like nothing more than having a bunch of people round, slapping a coat of paint on a room, making everyone play parlor games. She was given to directives like, “I believe in doing the thing you feel is right. If it looks right, it is right.” Not, perhaps, who you go to for insightful advice, but sometimes no-nonsense briskness is just the ticket.

Old etiquette guides are interesting on this point. They barely even address the issue of cancellation—because you didn’t do it. (Cell phones and email have a lot to answer for in that regard.) The one tangential piece of advice I found was in a book called Your Best Foot Forward: Social Usage for Young Moderns, published in 1940. “Examinations, minor illness, or extra work is not an adequate excuse for failing to observe the courtesy of guest to host,” the authors write sternly.

And if all else fails, I urge you to remember this cosmic law of the universe: it is never the people one wants to cancel who cancel. They never do. They need to read much more Graham Greene.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers

![Black_Mask_Mar_1941_[M][W]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1401282673i/9780150._SY540_.jpg)